Feeding Behavior, Body Weight and Growth Rate during Post-Deprivation Period in Rats ()

1. Introduction

When an organism is exposed to a water or food deprivation period, behavioral changes occur, affecting feeding patterns and body weight. Some of these changes include: a) feeding behavior adaptation to food availability periods [1] [2] ; b) increase in the consumption rate during the food availability period [3] ; c) general activity increase on experimental subjects [4] ; d) the production of stable states in the organism subjected to experimentation, which results from different deprivation conditions and levels [5] ; and of course, e) body weight loss. Deprivation of water or food has been an experimental tool widely used in several sciences (i.e., Experimental Psychology and Physiology) [6] [7] . Additionally, diverse studies have reported the effects that take place on feeding pattern during post-deprivation period [2] [8] - [10] . Hebb [11] observed that during the first free access day after a deprivation period, food consumption was smaller compared with that registered before deprivation. Collier, Hirsch and Kanareck [12] reported that during post-deprivation period, food consumption initiated with a sudden increase, maintaining until it gradually reached a stable maximum. Body weight increased as a result of food consumption changes, descending later until it finally returned to levels similar to those registered previous deprivation.

Siegel [10] , on the other hand, used different deprivation programs to characterize the rat consumption pattern. He observed that when a four-hour matutinal deprivation period ended, they ate as usual. Nevertheless, the same method applied nocturnally caused animals to increase their consumption after deprivation. These animals consumptions were compared with those presented by control subjects kept under free access throughout of experiment. Siegel [10] concluded that the time interval used in deprivation programs was related with food consumption when restriction finalized. Corwin and Buda-Levin [13] mentioned that deprivation periods exposure was an important element in the binge-eating type behavior development. They reported that repeated cycles of restriction/refeeding were a suitable model to study this type of behavior, especially when rats were used, because intake increase was the standard effect after deprivation was applied. Barbano and Cador [14] evaluated multiple feeding behavior components as function of deprivation level as well as palatability of the available food; their analysis indicated that anticipatory activity was mainly regulated by food restriction, whereas consumption and running for food were under the influence of homeostatic and food incentive mechanisms.

With this previous evidence, the role of deprivation on eating behavior is undeniable, especially over food consumption. Nevertheless, a great percentage of studies have only focused on analyzing food consumption changes while applying different deprivation programs. During the post-deprivation or refeeding period, other modifications that we consider necessary to evaluate, like changes in growth rate, water consumption or behavioral differences between males and females occur. This last variable is of special interest since a great percentage of studies only use male rats. There are few studies that report deprivation effects on post-deprivation feeding pattern in females [15] - [17] ; and in female and male reports, it is only possible to find experiments that evaluate feeding preferences [18] - [24] or diet effects on feeding pattern [25] - [28] .

This experiment purpose was, therefore, to explore food restriction and refeeding cycles effects on subsequent feeding behavior, body weight and growth rate in female and male rats. From evidence, we hypothesized that animals exposed to food deprivation would be more likely to show subsequent disturbances in eating patterns and behavior; specifically binge eating, binge drinking, body weight recovery and growth rate increase. Water and food consumption was registered before, during and after deprivation. Also variations on body weight and growth rate were analyzed. Experimental conditions were designed to evaluate deprivation effects on body weight, food and water intake, growth rate and sexual differences during post-deprivation period.

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Subject

Experimental subjects were 16 Winstar strain rats, 8 males (ME1, ME2, ME3, ME4, ME5 ME6, ME7, and M8) and 8 females (HE1, HE2, HE3, HE4, HE5, HE6, HE7, and HE8). Another 16 rats were control subjects (8 males: MC1, MC2, MC3, MC4, MC5, MC6, MC7, and MC8, and 8 females: HC1, HC2, HC3, HC4, HC5, HC6, HC7, and HC8). At the beginning of the experiment, female rats weighed 279 ± 14.7 g average and were 90 days old. Male rats weighed 413.85 ± 12.65 g (means ± SEM) and had the same age. Animals were singly housed in standard individual cages in an equipped room (21C +/− 2C) under a 12:12 light-dark cycle. All procedures in the present study were performed in accordance to the principles outlined by the Mexican Official Norm (NOM-062-ZOO-1999), Technical Specifications for the Production, Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

2.2. Apparatus

All experimental operations were performed in individual home cages, constructed of Plexiglas (13 × 27 × 38 cm), with sawdust on the bottom, which was changed every 3 days. We used a precision electronic scale for body weight and food consumption measurements.

2.3. Food

Standard Purina Roden Chow food for laboratory animals was used. Food consumption was registered in grams/ day and water consumption in ml/day.

2.4. Procedure

Rats were divided in two groups, experimental and control, equated by body weight. Experimental group (males n = 8, females n = 8) initiated with a 15 days baseline period to determine body weight, food and water intake. Food was removed the following morning at 9 h during 72 hours to initiate the first deprivation period. Subjects returned to free access conditions during a 15 days period. This food deprivation-free access cycle was repeated until completing three cycles (periods 1, 2 and 3). The lasted free access period lasted 30 days. Control group (males n = 8, females n = 8) had free access to food and water during all the experiment. Food and water intake, and body weight were measured daily.

2.5. Data Acquisition and Statistical Methods of Analysis

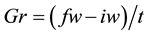

Data (food and water intake and body weight) was registered every day at 9 h in the morning, during 84 days. After data collection, we calculated means ± and standard error for body weight, food and water consumption, cumulative food intake and growth rate for both groups. Growth rate (Gr) was obtained as follows:

where fw represents the final weight and iw initial weight in a free access period; and t represents this period duration (in this case it was of 15 days). The last post-deprivation period was subdivided in two; from this subdivision periods 4 and 5 were obtained. A parametric contrast method, the Student’s t test was used to compare each group averages; since two independent groups of individuals were observed regarding a numerical variable under the assumptions of normality and equal variance. The graphics were created with Sigma Plot®.

3. Results

3.1. Body Weight

During the first 15 days there was no significant difference in the animals baseline weights (Figure 1). During the 72 h of the first food deprivation period, weight registered in experimental males was 375 ± 12 g (means ± SEM) versus control males 431.3 ± 13.2 g (means ± SEM) and experimental females 245 ± 13.2 g (means ± SEM) versus control females 286.1 ± 13.7 g (means ± SEM). Statistical difference was significant p < 0.01. In the post-deprivation period, weight loss was recovered. It took experimental males 15 days to reduce body weight difference to 443 ± 13.1 g (means ± SEM) compared with control males 454.8 ± 11 g (means ± SEM) P < 0.05, while it took experimental females 5 days to recover weight and show no significant difference with control females. Such body weight loss and recovery repeated itself in the following deprivation-post-depriva- tion cycles. Experimental and control subjects did not show significant differences in body weight at the end of the experiment.

3.2. Total Food Intake

Within the first 15 days total food intake was not statistical different (Figure 1). During deprivation periods, food consumption was 0 g for experimental subjects. During the first day of post-deprivation period, total food intake was significantly larger than during subsequent days (binge eating). The first total food intake was 37.3 ± 0.8 g (means ± SEM) for experimental males versus 28.5 ± 1.1 g (means ± SEM) for control males and experimental females consumed 26.25 ± 1 g (means ± SEM) versus control females 18.7 ± 0.5 g (means ± SEM) p < 0.01. Only experimental females maintained this increase on the total food consumption during 4 or 5 days, returning later to control subjects consumption levels. This food consumption increase repeated itself after every deprivation period.

![]()

Figure 1. Body weight, total food intake and total water intake of males and females, during 84 days, white circles represents experimental subjects during free access, gray circles represents experimental subjects during deprivation period and black circles represent control subjects. Values are means ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, significance of difference from control subjects. The white and black circles represents the average of two or three data.

3.3. Total Water Intake

Similarly to total food consumption, total water consumption during the baseline did not have a sadistically significant difference (Figure 1). During the food deprivation period, a water consumption reduction occurred (self-imposed deprivation). Water intake was 37.5 ± 5.2 ml (means ± SEM) for experimental males versus 56.2 ± 1.8 ml (means ± SEM) for control males, and experimental females drank 22.5 ± 3.6 ml (means ± SEM) versus control females 45 ± 1.8 ml (means ± SEM) p < 0.01. Nevertheless, when returned free access, experimental rats showed a significant increase in water consumption (binge drinking) compared to control subjects. Water intake was 81.8 ± 3.5 ml (means ± SEM) for experimental males versus 57.5 ± 1.6 ml (means ± SEM) for control males, and 68.1 ± 4.6 ml (means ± SEM) for experimental females versus 46.2 ± 1.8 ml (means ± SEM) p < 0.01 for control females. This result repeated itself in all post-deprivation periods.

3.4. Cumulative Food Intake

Throughout the experiment, cumulative food consumption did not present significant differences.

3.5. Growth Rate

During the first free access period, there was not statistically significant difference (Figure 2). The first free access post-deprivation period, presented statistically significant difference. Growth rate was 2.5 ± 0.2 g/day (means ± SEM) for experimental males versus 1.3 ± 0.12 g/day (means ± SEM) for control males; for experimental females 1.5 ± 0.6 g/day (means ± SEM) versus 0.6 ± 0.06 g/day (means ± SEM) for control females, p < 0.01. Statistical difference tended to get reduced; at the end of the experiment growth rate was .22 ± 0.11 g/day (means ± SEM) on experimental males versus 0.69 ± 0.13 g/day (means ± SEM) for control males, p < 0.05. Growth rate in experimental females versus control females was not significantly different during the last free access period.

3.6. Relation between Body Weight Recovery and Growth Rate

The relationship between body weight recovery and growth rate was an interesting finding. When body weight decreased during deprivation periods and recovering on the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th post-deprivation periods (free access) growth rate increased. However, during the 5th post-deprivation period, body weight recovery was related to a growth rate decrease (Table 1). This relation was clearer during the last 15-day period, in which statistical difference disappeared in females and significantly diminished in males.

![]()

Figure 2. Graphs represent the growth rate (g/day) during free access periods. The white circles represent experimental subjects and black circles control subjects. Values are means ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, significance of difference from control subjects.

![]()

Table 1. Comparison between body weight recovery and growth rate.

Results show an analysis of the data on post-deprivation periods. Means ± SEM of body weight and growth rate of experimental versus control groups was compared. Arrows indicate the relation between body weight and growth rate of experimental subjects.

4. Discussion

Findings clearly show that food deprivation causes important changes during post-deprivation period in males as much as in females. Post deprivation periods changes were, body weight recovery, binge eating, binge drinking related to self-imposed deprivation, and a growth rate increase. Post-deprivation changes were observed in both inter- and intra-subjects statistical analyses.

4.1. Body Weight Recovery by Growth Rate Increase

Previous weight regulation and compensatory growth studies have used models which expose animals to food deprivation programs. These studies outcomes have not taken post-deprivation growth rate increase into consideration [29] - [33] . In contrast, this experiment examined weight recovery associated with growth rate increase. Data indicated that growth rate increase was inversely proportional to body weight recovery during post-depri- vation periods. Statistical analyses indicated that the 15 days post-deprivation periods were sufficient to detect differences between groups. It is important to indicate that during the last 15 days of the experiment, statistical differences between groups disappeared. These data suggests that deprivation effect on post-deprivation periods has a limited duration, and confirm similar observations that have led some investigators to postulate that growth rate works as a compensatory mechanism, that regulates weight changes to maintain body weight [29] [34] [35] . Table 1 shows post-deprivation period growth rate data. Such information allows to conclude that weight recovery might be regulated by growth rate and does not exclusively depend on food consumption. Also the organism’s physical activity during the post-deprivation periods is a factor that can possibly modify growth rate; however, other experiments are necessary to explore which factors influence growth rate.

4.2. Binge Eating

The present experiment results support the findings of previous studies showing that deprivation increases food intake during post-deprivation periods [36] -[39] . Several studies have considered that food restriction and binge eating co-occur [36] [37] [40] . Our results demonstrated that this relation appeared during all deprivation-post- deprivation cycles (Figure 1). Statistical analyses indicated that difference in food consumption between experimental and control groups was statistically significant (p < 0.01) during the first 2 days in males and the first 4 - 6 days in females during post-deprivation periods. These data suggest that binge eating might be a regulatory behavior that appears only during the first days of the post-deprivation period. This is supported by total food intake analyses. No statistical differences in accumulative food intake between experimental and control group was observed, suggesting that the general food consumption pattern was not modified. This result supports the alternative explanation of binge eating as a regulatory behavior.

4.3. Binge Drinking by Self-Imposed Deprivation

Polydipsia is a stereotyped pattern of drinking that can be caused by a variety of pathological or experimental factors [41] [42] . In order to understand the water consumption increase causes, several types of animal polydipsia models have been developed: a) traumatic (e.g., supraoptic nucleus lesions in the hypothalamus) [43] ; b) pathological (e.g., diabetes) [44] [45] ; c) schedule-induced polydipsia, [46] [47] ; and d) drugs-induced polydipsia [48] [49] . The basic characteristic of polydipsia is its temporary persistence maintained by: programs, drugs or diseases. Our results show a different type of increase in water consumption. The term “binge drinking” is used to refer to post-deprivation water over consumption, due to its similarities with binge eating. Statistical analyses indicated that water consumption between experimental and control groups was statistically significant (p < 0.01) only during the first day of post-deprivation period (binge drinking) in males and females. This data suggests that self-imposed water deprivation, food deprivation and binge drinking co-occur, as with binge eating (Figure 1).

4.4. Differences between Females and Males

These results suggest that, the deprivation program had the same effect in females and males, that is to say, no differences were observed in the body weight recovery, binge eating or binge drinking. Sefcikova and Mozes [15] reported that adult female rats showed overfeeding episodes when they were exposed to nutrients restriction periods previously. They concluded that a relation between the experience with restrictive diet and food consumption changes include overfeeding. On the other hand, Kennedy [50] indicated that females and males rats show differences in their body weight regulation, because males are more responsive to feeding signals than females. Nevertheless, results obtained on the present experiment did not show differences in body weight recovery between females and males in the post-deprivation periods. The exposition to other types of foods, could possibly determine some type of differences in body weight and food consumption between males and females. For example, it has been observed that female rats consume more sweetened solutions than males, especially when those contain calories [51] [52] . Apparently, sex can represent an important variable on eating behavior study.

4.5. Limitations

Binge eating and binge drinking inadequate operational characterization was a limitation for this study. Scientific evidence has identified these two types of behavior, from an increase of food and water consumption compared to baseline [13] [38] [39] [53] . However, exactly determining the increment amount or percentage that characterizes this type of behavior is still a pending task. Another limitation was the 24 hour consumption measurement, because to identify the time and conditions under which binge eating and binge drinking are presented, is necessary to perform a day long analysis.

5. Conclusion

It seems reasonable to conclude that food deprivation modifies multiple factors during the post-deprivation period. These changes are called post-deprivation effects. Binge eating and binge drinking are related to deprivation and its nature seems to be regulatory due to the fact that it disappears when deprivation is retired. Body weight recovery is related to growth rate. Further work is necessary to clarify which factors influence growth rate, and to explore deprivation intensity variations and their effects on binge eating, binge drinking and self- imposed deprivation.

Acknowledgements

The research is financed by CONACYT project-CB 156821.