The Extension of Cauchy Integral Formula to the Boundaries of Fundamental Domains ()

1. Introduction

We make reference to [1] for elementary knowledge in complex analysis used below. It is known (see [2]) that for every rational function

of degree n the complex plane can be partitioned into n sets whose interior are fundamental domains of

, i.e. they are mapped conformally (hence bijectively) by

onto the whole complex plane with some slits. A similar partition takes place for transcendental functions (see [3]), except that for those functions the number of fundamental domains is infinite. Every fundamental domain

of an analytic function

is either unbounded or

contains singular points of

, or both.

Although integrals on unbounded contours have been used frequently in complex analysis (see [1], page 214), they have never appeared in the context of Cauchy integral formula. The main novelty of this paper is that it makes possible such an undertaking. The famous Cauchy integral formula is in this way upgraded from a rather local instrument to a more global one. Moreover, it shows that the functions we are studying are completely determined by the values on the boundaries of their fundamental domains.

The integral on

of

shall be treated as an improper integral the convergence of what remains to be investigated. This can be accomplished in different ways which apply to particular classes of functions; hence instead of trying to prove theorems valid for any analytic function, we must treat separately those classes of functions. However, the techniques used are in general similar; namely they consist in isolating the singular points and

by the pre-image of some circles whose radii are let tend to zero, respectively to infinity, then in applying the Cauchy integral formula to the bounded sub-domains of

obtained in this way and making sure that the integrals on the boundaries of the complementary domains tend to zero when the radii tend to zero or to infinity. As

is injective in every fundamental domain, if such a domain is mapped conformally by the function onto the complex plane with a slit; then for some values

there is a function

corresponding to that fundamental domain such that

,

. The function

is injective in the interval

and maps this interval onto an arc

included in that fundamental domain. Making the change of variable

in the integral

it becomes an integral on the interval

and it is possible that it tends to zero as

or

. This assertion should be checked for every particular class of functions.

The contours we used for integration needed to be illustrated and most of the graphics are computer generated by the software Mathematica. When this was not possible, we used illustration by hand made drawings. However, they are pictures of known fundamental domains (see [1], page 268 and 282). One of the most studied classes of meromorphic functions is that of Dirichlet functions and it can be considered as a prototype in many aspects. Let us start then with this class.

2. General Properties of Dirichlet Functions

The Dirichlet functions are obtained by analytic continuation of general Dirichlet series across the line of convergence. The family of general Dirichlet series includes that of well known Dirichlet L-series defined by Dirichlet characters. These last series can be all extended as meromorphic functions in the whole complex plane. The extended functions are called Dirichlet L-functions. They are implemented in Mathematica and some affirmations about general Dirichlet functions are illustrated by using Dirichlet L-functions. However, the interest in more general functions is obvious and we have recently devoted to them a lot of publications (see [2] - [15]). An account of recent advances in this field can be found in [8].

A general Dirichlet series

is defined by an arbitrary sequence of complex numbers

, the coefficients of the series and by a non decreasing sequence of non negative numbers

, the exponents of the series. It is given by the formula

(1)

We will deal only with normalized general Dirichlet series in which

and

. For such a series we have

uniformly with respect to t (see [8], Theorem 3). There is a number

, called the abscissa of convergence of

,

such that the series (1) converges for

and it diverges for

. The series converges uniformly on compact subsets of

and therefore it is an analytic function in that half plane. Denoting by

we have proved in [8] that if the abscissa of convergence of

is finite then the abscissa of convergence of

is zero and if

has only isolated singular points on

, then

can be continued across the line

to a meromorphic function in the whole complex plane. We keep the notation

for the extended function when it exists and we call it Dirichlet function. Following Speiser [16], who studied the Riemann Zeta function, we have used in [2] - [15] the pre-image of the real axis by

. This is the set of points in the s-plane where

takes real values. For every Dirichlet function it is a family of analytic curves whose structure has very profound implications on the value distribution of that function. Figure 1(a) illustrates the pre-image of the real axis by a Dirichlet L-function defined by a complex Dirichlet character and Figure 1(b) by a real one. Details about Figure 1(c) are found in Section 3.

We have proved (see for example [8]) that for any Dirichlet function

this pre-image is formed with unbounded curves (components) which fall into three categories. Namely, there are infinitely many curves

, which do not intersect each other and consecutive

and

(

below

) form infinite strips

extending for

going from

to

. The counting is such that

. Every curve

is mapped homeomorphycally by

onto the interval

of the real axis and therefore every

-strip is mapped (not necessarily one to one) onto the whole complex plane with a slit alongside this interval. For

every strip

contains a unique component

of the pre-image of the real axis which is mapped homeomorphycally by

onto the interval

of the real axis and a finite number of components

which are mapped each one homeomorphycally by

onto the whole real axis. The component

![]()

Figure 1. The pre-image of the real axis by Dirichlet L-functions.

extends for

going from

to

, while

are parabola shaped curves with a finite supremum of

, therefore we can distinguish the interior and the exterior of such a curve.

In the case of a strip

, if

then connecting

with

by a Jordan arc

the component of the pre-image of

passing through

can be an unbounded curve

, when for

we have

. On the other hand the origin of such a curve must be a point

on a curve

such that

. The curve

is bounded when its ends belong to different curves

and

. This is the case when

and

are embraced curves (see [8]) and when

. The curve

is mapped 2 to 1 by

onto

. Then we can form fundamental domains using parts of the curves

, the curves

(and

, when is the case, as in Figure 2). These are strips unbounded to the right and to the left when

is unbounded and they are bounded to the right when

is bounded. They are mapped conformally by

onto the whole complex plane with some slits alongside the interval

of real axis and some other slits alongside

.

In the case of the strip

, when the zeros of

are complex, the curves

are all bounded for

and together with

they form the

![]()

Figure 2. Conformal mapping of fundamental domains by

.

boundaries of fundamental domains bounded to the right. It is known (see, for example [13]) that every

-strip,

of

can be partitioned into a finite number of sets whose interior are fundamental domains of

. The

-strip contains infinitely many fundamental domains. The way they are mapped conformally onto the complex plane with some slits by the Riemann Zeta function is illustrated in Figure 2 (see [13], Figure 6).

3. Cauchy Integral Formula for Fundamental Domains and Sk-Strips of the Function

The Cauchy integral formula has the form:

(2)

where the function

is analytic in a simply connected domain D containing the simple closed contour C and

is an arbitrary point inside C.

We would like

to be a Dirichlet function

and C to be the boundary

of a fundamental domain

of

or the boundary

of an

-strip. The problem is that

and

are not simple closed contours. However, we can show that the formula (2) can be extended to these curves.

The shape of the fundamental domains of

depends on the pre-image of the real axis and on the zeros of

. Since

is injective in every fundamental domain the zeros of

must be located on the boundaries of these domains. Figure 3 portrays a fundamental domain

of

bounded by a curve

, the part of the last curve

from

on which

vary from

to

, where we have

, as well as the pre-image of the segment determined by

and

where

is the zero of

the closest to

. The pre-image

of the circle

and the pre-image

of the circle

are also drawn, where r is big enough and

is small enough. Figure 1(c) illustrates computer generated pre-images of these circles for

(the orange curve)

![]()

Figure 3. A fundamental domain of

and its conformal mapping.

and

(the green curve). It has been worked by Florin Alan Muscutar. Due to the continuity of

at

and to the fact that

is a normalized Dirichlet series, the arc

squeezes to the point

and

with s on

tends to

as

. Also

with s on

tends to

as

.

The domain

is mapped conformally by

onto the complex plane with a slit alongside the subinterval

of the real axis and alongside the segment determined by

and

. Also, the domain

is mapped conformally onto the ring domain

determined by the two circles with the corresponding slit (see Figure 3). The function

is analytic in a domain containing

and therefore the Cauchy integral formula is valid for

.

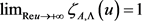

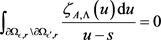

Theorem 1. If we denote by

the infinite strip obtained from

as

, then for every

we have

(3)

Proof: Let us take

. Then the pre-image of the circle

intersected with

is formed with two arcs

inside

and

at the right of

. The arcs

and the curves

and

determine a curvilinear quadrilateral whose conformal module is the same as that of the quadrilateral determined by

, the real axis and the segment from

to

, which in turn is less than the conformal module of the ring domain

. It is known (see [17], page 31) that the value of this last module is

. If we take

then this module is

, which shows that the length of

remains bounded as

, since otherwise the respective module would tend to

, contrary to the fact that it remains constant . Let us evaluate

. Let us evaluate . Since

. Since  we have that

we have that  and since the length of

and since the length of  remains bounded we have

remains bounded we have .

.

On the other hand, by Cauchy theorem  does not depend on

does not depend on  since

since . Then we can let

. Then we can let  in

in  and we obtain (3).

and we obtain (3).

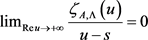

It is not clear what happens with  as

as . Making the change of variable

. Making the change of variable , where

, where , which is allowed since

, which is allowed since ![]() is injective on

is injective on![]() , we get

, we get![]() .

.

Although the integrand tends to zero as![]() , a limitation of the initial integral is problematic, due to the factor

, a limitation of the initial integral is problematic, due to the factor ![]() in the last term. So, as long as we cannot make sure that

in the last term. So, as long as we cannot make sure that ![]() tends to zero as

tends to zero as![]() , the problem of extending the Cauchy integral formula to the whole fundamental domain remains unsolved.

, the problem of extending the Cauchy integral formula to the whole fundamental domain remains unsolved.

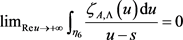

Theorem 2. Let ![]() be an arbitrary strip of the function

be an arbitrary strip of the function ![]() as defined in Section 2 and for r big enough let

as defined in Section 2 and for r big enough let ![]() be the part of the pre-image by

be the part of the pre-image by ![]() of the circle

of the circle ![]() included in

included in![]() . We denote by

. We denote by ![]() the part of the strip

the part of the strip ![]() bounded at the left by

bounded at the left by![]() . Then for every

. Then for every ![]() we have:

we have:

![]() (4)

(4)

Proof: For an arbitrary ![]() and for the given r, let us build the domains

and for the given r, let us build the domains ![]() as in Theorem 1 corresponding to every fundamental domain

as in Theorem 1 corresponding to every fundamental domain![]() . The sum of the corresponding arcs

. The sum of the corresponding arcs ![]() from these domains is

from these domains is ![]() and the sum of the corresponding arcs

and the sum of the corresponding arcs ![]() is an arc

is an arc ![]() connecting

connecting ![]() and

and![]() . The arcs

. The arcs ![]() squeeze each one to the respective points

squeeze each one to the respective points ![]() when

when![]() , where

, where![]() .

.

Since for each arc ![]() we have

we have ![]() it results that

it results that![]() . Denoting by

. Denoting by ![]() the domain bounded by

the domain bounded by ![]() and the arcs

and the arcs ![]() we see that this domain becomes

we see that this domain becomes ![]() when

when![]() . On the other hand, the Cauchy integral formula is applicable to

. On the other hand, the Cauchy integral formula is applicable to![]() , i.e. for every

, i.e. for every ![]() we have

we have ![]() and then at the limit as

and then at the limit as ![]() this equality becomes (4) and the theorem is proved.

this equality becomes (4) and the theorem is proved.

We notice that this theorem says that the values of ![]() are completely determined by its values greater than 1 and those taken on an arbitrary circle of radius big enough. Moreover, the integral of the formula (4) is always convergent.

are completely determined by its values greater than 1 and those taken on an arbitrary circle of radius big enough. Moreover, the integral of the formula (4) is always convergent.

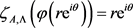

If ![]() is the parametric equation of

is the parametric equation of ![]() such that

such that ![]() then the formula (4) becomes

then the formula (4) becomes

![]() (5)

(5)

We notice that![]() , hence the first integral in (5) is an improper integral. By Theorem 1 this integral is always convergent.

, hence the first integral in (5) is an improper integral. By Theorem 1 this integral is always convergent.

The function ![]() is not injective in

is not injective in![]() , hence the integrals (4) and (5) give us the same value for different points s in

, hence the integrals (4) and (5) give us the same value for different points s in![]() . If we would like to have a unique point corresponding to a given value, then we need to use the formula (3).

. If we would like to have a unique point corresponding to a given value, then we need to use the formula (3).

Also, taking into account the fact that the domain interior to every curve![]() , which is not embracing curve, is mapped conformally and therefore injectively by

, which is not embracing curve, is mapped conformally and therefore injectively by ![]() onto the upper or the lower half plane, a unique point s from that domain corresponds to every given value from the respective half plane. Then the following formula is true for every r big enough:

onto the upper or the lower half plane, a unique point s from that domain corresponds to every given value from the respective half plane. Then the following formula is true for every r big enough:

![]() (6)

(6)

where ![]() is the boundary of the domain bounded by

is the boundary of the domain bounded by ![]() and the pre-image of the circle

and the pre-image of the circle![]() .

.

If the equation of the curve ![]() is

is ![]() such that

such that ![]() then the formula (6) becomes

then the formula (6) becomes

![]() (7)

(7)

where![]() .

.

4. The Distribution of the Values of a Dirichlet Function

The contour of integration in Theorem 2 is simpler than that appearing in Theorem 1. However, (3) has the advantage of representing a univalent function in![]() . The pre-image of the circle

. The pre-image of the circle ![]() intersects several components of the pre-image of the interval

intersects several components of the pre-image of the interval ![]() of the real axis situated in

of the real axis situated in![]() , more exactly if

, more exactly if ![]() has m zeros in

has m zeros in![]() , then this pre-image intersects exactly

, then this pre-image intersects exactly ![]() such components, hence it traverses m fundamental domains. Each one of these domains contains a unique point

such components, hence it traverses m fundamental domains. Each one of these domains contains a unique point ![]() such that

such that![]() . A point on the circle

. A point on the circle ![]() should turn m times around the origin for its pre-image to traverse the m fundamental domains going from

should turn m times around the origin for its pre-image to traverse the m fundamental domains going from ![]() to

to![]() . At every turn it assigns a unique point

. At every turn it assigns a unique point ![]() where

where ![]() takes the same value. Since

takes the same value. Since ![]() is univalent in

is univalent in ![]() that value is completely determined by the values on

that value is completely determined by the values on ![]() and

and![]() .

.

5. Extension of Cauchy Integral Formula for the Derivatives of Dirichlet Functions

Following the known technique of computing ![]()

we find that

![]() (8)

(8)

Thus, as for ![]() the values of

the values of ![]() are completely determined in every strip

are completely determined in every strip ![]() by the real values greater than 1 of

by the real values greater than 1 of![]() . By recursive computation we find that:

. By recursive computation we find that:

![]() (9)

(9)

for every natural number n.

It is known (see [4] and Figure 4) that if a Dirichlet L-function ![]() has m zeros in the strip

has m zeros in the strip ![]() then

then ![]() has

has ![]() zeros in

zeros in ![]() (which are all simple zeros).

(which are all simple zeros).

This figure illustrates the following:

Theorem 3. If ![]() has m fundamental domains in

has m fundamental domains in ![]() then every derivative

then every derivative ![]() has exactly

has exactly ![]() zeros in

zeros in![]() .

.

Proof: The pre-image by ![]() of a circle

of a circle ![]() has m components in

has m components in ![]() which are disjoint if r is small enough. By letting r increase these components expand and after two of them touch each other, they fuse into a unique component including the corresponding zeros. When

which are disjoint if r is small enough. By letting r increase these components expand and after two of them touch each other, they fuse into a unique component including the corresponding zeros. When ![]() a unique component becomes unbounded with branches tending to

a unique component becomes unbounded with branches tending to ![]() with

with![]() . The remaining bounded components are outside this unbounded one and none of them can intersect

. The remaining bounded components are outside this unbounded one and none of them can intersect![]() . Increasing r past 1 the unbounded components from all the strips

. Increasing r past 1 the unbounded components from all the strips ![]() fuse into a unique unbounded component crossing these strips. After touching bounded components of the pre-image of the circle

fuse into a unique unbounded component crossing these strips. After touching bounded components of the pre-image of the circle ![]() with

with ![]() (if such components exist in a given

(if such components exist in a given![]() ), these last components are absorbed into the unbounded one and the corresponding zeros of

), these last components are absorbed into the unbounded one and the corresponding zeros of ![]() pass

pass

![]()

Figure 4. The zeros of ![]() and those of its first two derivatives for

and those of its first two derivatives for![]() .

.

to the right of it. For r big enough all the zeros of ![]() from the strip

from the strip ![]() will be at the right of the unbounded component of the pre-image of the circle

will be at the right of the unbounded component of the pre-image of the circle![]() . That value of r depends on

. That value of r depends on![]() .

.

The points where two components of the pre-image of a circle ![]() touch each other are the zeros of

touch each other are the zeros of![]() . A complete binary tree can be formed having as leaves the zeros of

. A complete binary tree can be formed having as leaves the zeros of ![]() and as internal nodes these touching points. It is known from the graph theory that if a complete binary tree has m leaves then it has exactly

and as internal nodes these touching points. It is known from the graph theory that if a complete binary tree has m leaves then it has exactly ![]() internal nodes. This proves that

internal nodes. This proves that ![]() has

has ![]() zeros in

zeros in![]() . The zeros of the second derivative are obtained in a similar way, yet since

. The zeros of the second derivative are obtained in a similar way, yet since![]() , there will be m components of the pre-image by

, there will be m components of the pre-image by ![]() of the circle

of the circle ![]() for r small enough, even if there are only

for r small enough, even if there are only ![]() zeros of

zeros of![]() . One of these components contains no such a zero. These components touch each other at the zeros of

. One of these components contains no such a zero. These components touch each other at the zeros of ![]() and by the previous analysis there should be

and by the previous analysis there should be ![]() zeros of

zeros of![]() . The same procedure can be applied to derivatives of any higher order and the theorem is completely proved.

. The same procedure can be applied to derivatives of any higher order and the theorem is completely proved.

Figure 5 portraying the pre-image of the real axis by the Riemann Zeta function and by its derivative shows that their ![]() -strips and their fundamental domains overlap, but they do not completely coincide (see [11]). However, the

-strips and their fundamental domains overlap, but they do not completely coincide (see [11]). However, the

![]()

Figure 5. The pre-image of the real axis by ![]() and

and![]() .

.

integral (8) gives the same value for ![]() as

as

![]() (10)

(10)

since if ![]() is the corresponding strip of

is the corresponding strip of ![]() the integral on

the integral on ![]() is zero, by Cauchy Theorem. The same is true for the integrals on the boundaries of the corresponding fundamental domains of the two functions.

is zero, by Cauchy Theorem. The same is true for the integrals on the boundaries of the corresponding fundamental domains of the two functions.

6. Extension of Cauchy Integral Formula to Fundamental Domains of Modular Function

By the Riemann mapping theorem there is a unique analytic function ![]() mapping conformally the domain D bounded by the half lines

mapping conformally the domain D bounded by the half lines![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() and the half circle

and the half circle ![]() onto the upper half plane

onto the upper half plane ![]() such that

such that![]() ,

, ![]() and

and![]() . The function

. The function ![]() can be continued by symmetry into the upper half plane as in Figure 6.

can be continued by symmetry into the upper half plane as in Figure 6.

The symmetric domain ![]() of D with respect to the imaginary axis is mapped conformally by

of D with respect to the imaginary axis is mapped conformally by ![]() onto the lower half plane and

onto the lower half plane and ![]() is mapped conformally onto the whole complex plane with the slit

is mapped conformally onto the whole complex plane with the slit![]() , alongside the real axis, hence

, alongside the real axis, hence ![]() is a fundamental domain of

is a fundamental domain of![]() . In fact the union any two adjacent domains bounded by the half circles above (the half lines can be considered half circles too!) and the common half circle is a fundamental domain of

. In fact the union any two adjacent domains bounded by the half circles above (the half lines can be considered half circles too!) and the common half circle is a fundamental domain of![]() . For example

. For example ![]() is mapped conformally by

is mapped conformally by ![]() onto the whole complex plane with the slit

onto the whole complex plane with the slit ![]() and

and ![]() is mapped conformally by

is mapped conformally by ![]() onto the

onto the

![]()

Figure 6. Continuation by symmetry of the modular function.

whole complex plane with the slit ![]() etc. So, Figure 6 exhibits a partition of the upper half plane into fundamental domains of

etc. So, Figure 6 exhibits a partition of the upper half plane into fundamental domains of![]() . Each one of these half circles ends up into a singular point of

. Each one of these half circles ends up into a singular point of![]() , therefore these singular points form a dense subset of the real axis, which implies that

, therefore these singular points form a dense subset of the real axis, which implies that ![]() cannot be continued across the real axis and its full domain of definition is the upper half plane.

cannot be continued across the real axis and its full domain of definition is the upper half plane.

The way the function ![]() has been constructed implies that for every s in the upper half plane we have

has been constructed implies that for every s in the upper half plane we have ![]() and

and ![]() and then (see [1], page 280)

and then (see [1], page 280) ![]() uniformly with respect to

uniformly with respect to![]() . Hence the part of the pre-image by

. Hence the part of the pre-image by ![]() of the circle

of the circle ![]() included in

included in ![]() is an arc

is an arc![]() :

:![]() ,

, ![]() , where

, where ![]() uniformly with respect to

uniformly with respect to![]() . In particular, denoting by

. In particular, denoting by ![]() the inverse of

the inverse of ![]() in

in![]() , we have

, we have ![]() as

as![]() .

.

On the other hand, the part of the pre-image by ![]() of the circle

of the circle ![]() included in

included in ![]() is formed for r big enough with two arcs

is formed for r big enough with two arcs ![]() and

and ![]() such that for

such that for ![]() we have

we have ![]() as

as ![]() and for

and for ![]() we have

we have ![]() as

as![]() . Let us denote by

. Let us denote by ![]() the part of

the part of ![]() obtained by removing the pre-image of the set

obtained by removing the pre-image of the set![]() .

.

Theorem 4. For any fundamental domain ![]() of the function

of the function ![]() and any point

and any point ![]() we have:

we have:

![]() (11)

(11)

Proof: Let us deal first with the fundamental domain

![]() . By isolating the point

. By isolating the point ![]() with a small circle

with a small circle ![]() and the point

and the point ![]() with a big circle

with a big circle ![]() and by removing from

and by removing from ![]() the pre-image of the disc

the pre-image of the disc ![]() and of the exterior of the disc

and of the exterior of the disc ![]() we obtain a bounded domain

we obtain a bounded domain ![]() for which the Cauchy integral formula is applicable: for any

for which the Cauchy integral formula is applicable: for any ![]() we have

we have![]() . Taking

. Taking ![]() and having in view the Cauchy theorem we conclude that

and having in view the Cauchy theorem we conclude that ![]() and since

and since![]() , we can set

, we can set ![]() and get (11).

and get (11).

Now, if we take for example ![]() and proceed similarly, the new

and proceed similarly, the new ![]() is the part of the pre-image of the circle

is the part of the pre-image of the circle ![]() included in D, hence again.

included in D, hence again.

![]() and the extension of the Cauchy integral formula is true for the new unbounded domain

and the extension of the Cauchy integral formula is true for the new unbounded domain![]() . We are brought to the same conclusion when

. We are brought to the same conclusion when![]() .

.

This theorem tells us that the modular function is completely determined by its real values and by the values on the pre-image of an arbitrary big circle centered at the origin.

7. Extension of Cauchy Integral Formula to the Fundamental Domains of the Exponential Function

It is known that the horizontal strips bounded by consecutive lines ![]() are fundamental domains

are fundamental domains ![]() of the exponential function

of the exponential function![]() . The function

. The function ![]() maps conformally each one of these strips onto the complex plane with the slit alongside the positive real half axis. The pre-image by

maps conformally each one of these strips onto the complex plane with the slit alongside the positive real half axis. The pre-image by ![]() of the circle

of the circle ![]() is the vertical line

is the vertical line ![]() and if we denote by

and if we denote by ![]() the intersection of this line with any fundamental domain of

the intersection of this line with any fundamental domain of ![]() then

then ![]() and at the limit as

and at the limit as ![]() we get an indetermination of the form

we get an indetermination of the form![]() . Thus

. Thus ![]() might be divergent. However, we can prove:

might be divergent. However, we can prove:

Theorem 5. For any fundamental domain ![]() of

of ![]() and for any positive number r, if we denote

and for any positive number r, if we denote ![]() we have

we have

![]() (12)

(12)

where ![]() is an arbitrary point of

is an arbitrary point of![]() .

.

Proof: The intersection of the pre-image by ![]() of the annulus

of the annulus ![]() and

and ![]() is a bounded domain

is a bounded domain ![]() and for every

and for every ![]() we have

we have

![]() (13)

(13)

In order to obtain (12) it will be enough to show that![]() , where

, where ![]() is

is![]() . This integral is

. This integral is ![]() and since the integrand is bounded and

and since the integrand is bounded and ![]() we obtain at the limit the formula (12).

we obtain at the limit the formula (12).

8. The Case of Trigonometric Functions

We illustrate this case by dealing with the function ![]() (see [9], page 51). for which the fundamental domains are vertical half strips

(see [9], page 51). for which the fundamental domains are vertical half strips ![]() determined by the lines

determined by the lines![]() ,

, ![]() and

and![]() , symmetric of

, symmetric of ![]() with respect to the real axis. They are mapped conformally by the function

with respect to the real axis. They are mapped conformally by the function ![]() onto the complex plane with a slit alongside the interval

onto the complex plane with a slit alongside the interval![]() . For

. For![]() , the pre-image of the circle

, the pre-image of the circle ![]() is the curve of equation

is the curve of equation![]() . An elementary computation shows that this equation is equivalent to

. An elementary computation shows that this equation is equivalent to![]() . This show that

. This show that ![]() in Ωj and

in Ωj and ![]() in

in ![]() and

and ![]() when

when![]() , respectively

, respectively ![]() when

when![]() . Hence the pre-image of the circle

. Hence the pre-image of the circle ![]() is formed with two sinusoidal curves symmetric with respect to the real axis. Moreover,

is formed with two sinusoidal curves symmetric with respect to the real axis. Moreover, ![]() in

in ![]() and

and ![]() in

in ![]() uniformly with respect to x when

uniformly with respect to x when ![]() is on either one of these curves. Let us denote by

is on either one of these curves. Let us denote by ![]() the part of this pre-image situated in

the part of this pre-image situated in![]() . We would like to evaluate

. We would like to evaluate![]() . For every domain

. For every domain ![]() there is an analytic function

there is an analytic function ![]() such that

such that![]() . Then making the change of variable

. Then making the change of variable ![]() in this integral we get

in this integral we get![]() .

.

Let us notice that ![]() and we need to chose the sine minus in the last term since if to

and we need to chose the sine minus in the last term since if to ![]() corresponds

corresponds ![]() then to

then to ![]() corresponds

corresponds![]() , hence

, hence ![]() is an odd function of

is an odd function of![]() .

.

By making the change of variable![]() , we get

, we get

![]() (14)

(14)

When r is big enough the term ![]() varies very little as

varies very little as ![]() varies from

varies from ![]() to

to![]() . Assuming a constant instead of this term, what it remains to integrate between

. Assuming a constant instead of this term, what it remains to integrate between ![]() and

and ![]() is an odd function, hence the integral is zero. This doesn’t necessarily mean that

is an odd function, hence the integral is zero. This doesn’t necessarily mean that![]() . However, the previous remark justifies the conjecture that this limit is true and therefore the Cauchy integral formula extends to the boundaries of the fundamental domains of the function

. However, the previous remark justifies the conjecture that this limit is true and therefore the Cauchy integral formula extends to the boundaries of the fundamental domains of the function![]() .

.

9. Extension of Cauchy Integral Formula to the Fundamental Domains of the Weierstrass ![]() Function

Function

The Weierstrass ![]() function is defined (see [1], page 272) by the formula

function is defined (see [1], page 272) by the formula

![]() (15)

(15)

where the sum ranges over all![]() , where

, where ![]() with

with ![]() and

and ![]() arbitrary complex numbers having non real ratio

arbitrary complex numbers having non real ratio![]() . It is known that

. It is known that ![]() is a doubly periodic function with the periods

is a doubly periodic function with the periods ![]() and

and![]() . Hence it is sufficient to know the values of

. Hence it is sufficient to know the values of ![]() into the (fundamental) parallelogram determined by

into the (fundamental) parallelogram determined by ![]() and

and ![]() in order to be able to find its values anywhere in the complex plane. The series (15) converges uniformly and absolutely on any compact subset of

in order to be able to find its values anywhere in the complex plane. The series (15) converges uniformly and absolutely on any compact subset of ![]() which does not contain points

which does not contain points![]() , therefore it is a meromorphic function in the complex plane. The points

, therefore it is a meromorphic function in the complex plane. The points ![]() are double poles for

are double poles for ![]() and hence they are triple poles for

and hence they are triple poles for![]() .

.

It can be easily shown that![]() . Moreover, since

. Moreover, since![]() , by denoting

, by denoting![]() , we have

, we have![]() , thus z and

, thus z and ![]() are symmetric with respect to the center of the fundamental parallelogram, hence if we know the values of

are symmetric with respect to the center of the fundamental parallelogram, hence if we know the values of ![]() in one of the triangles determined by a diagonal of the parallelogram, then we know its values in the whole parallelogram. Also,

in one of the triangles determined by a diagonal of the parallelogram, then we know its values in the whole parallelogram. Also, ![]() takes the same value at points symmetric with respect to the middle of each one of the sides of this triangle. Since the function is univalent in the triangle and maps each side two to one onto some curve originating in the image of the middle of the respective side and going to infinity (the ends of each side being poles) we conclude that these triangles are fundamental domains of

takes the same value at points symmetric with respect to the middle of each one of the sides of this triangle. Since the function is univalent in the triangle and maps each side two to one onto some curve originating in the image of the middle of the respective side and going to infinity (the ends of each side being poles) we conclude that these triangles are fundamental domains of![]() . Let us denote

. Let us denote![]() ,

, ![]() and

and![]() . Then

. Then ![]() maps conformally every fundamental triangle onto the whole complex plane with infinite slits originating at

maps conformally every fundamental triangle onto the whole complex plane with infinite slits originating at ![]() and

and![]() . Figure 7 illustrates this situation. It shows also that each one of the domains

. Figure 7 illustrates this situation. It shows also that each one of the domains ![]() is mapped conformally onto the corresponding domain

is mapped conformally onto the corresponding domain ![]() with two sides of

with two sides of ![]() going onto the slits. From the

going onto the slits. From the

![]()

Figure 7. Fundamental triangle of ![]() and its conformal mapping.

and its conformal mapping.

differential equation of ![]() (see [1], page 278) is obvious that

(see [1], page 278) is obvious that![]() , which implies that the triangle with vertices

, which implies that the triangle with vertices ![]() contains the origin, hence

contains the origin, hence ![]() has a zero in the domain

has a zero in the domain ![]() and, obviously another one in the symmetric domain with respect to

and, obviously another one in the symmetric domain with respect to ![]() (These might have been unknown facts until now!).

(These might have been unknown facts until now!).

Theorem 6. The Cauchy integral formula can be extended to any fundamental domain of the Weierstrass ![]() function .

function .

Proof: For r big enough the circle ![]() is intersecting every slit of

is intersecting every slit of ![]() and the pre-image by

and the pre-image by ![]() of the domain

of the domain ![]() is formed with infinitely many connected open sets covering each one a vertex of the period parallelograms. The function

is formed with infinitely many connected open sets covering each one a vertex of the period parallelograms. The function ![]() is analytic on the complementary set of this pre-image. In particular, the Cauchy integral formula is applicable to any fundamental triangle from which that pre-image has been removed. If we denote by

is analytic on the complementary set of this pre-image. In particular, the Cauchy integral formula is applicable to any fundamental triangle from which that pre-image has been removed. If we denote by ![]() such a set, then we have:

such a set, then we have:

![]() (16)

(16)

for every![]() . Due to the univalence of

. Due to the univalence of ![]() in

in![]() , it has an inverse function

, it has an inverse function ![]() defined in the disc

defined in the disc![]() . Thus,

. Thus,![]() . With the change of variable

. With the change of variable![]() , the integral on the part of

, the integral on the part of ![]() belonging to the pre-image of the circle

belonging to the pre-image of the circle ![]() becomes

becomes

![]() (17)

(17)

Since the points ![]() are triple poles

are triple poles ![]() the term

the term ![]() tends to infinity as fast as

tends to infinity as fast as ![]() when

when ![]() therefore the integrand in (18) tends to zero as

therefore the integrand in (18) tends to zero as![]() . If we denote by

. If we denote by ![]() any fundamental domain of

any fundamental domain of![]() , then this limit guarantees the absolute convergence of the improper integral

, then this limit guarantees the absolute convergence of the improper integral ![]() and the fact that for every

and the fact that for every ![]() we have:

we have:

![]() (18)

(18)

which represents the extension of Cauchy integral formula to the fundamental domains of the Weierstrass ![]() function. It asserts that the function is completely determined by its values on the boundary of any fundamental triangle.

function. It asserts that the function is completely determined by its values on the boundary of any fundamental triangle.

Theorem 7. For any fundamental domain ![]() of

of ![]() and for every point

and for every point ![]() the value of an arbitrary derivative

the value of an arbitrary derivative ![]() at

at ![]() is given by the formula:

is given by the formula:

![]() (19)

(19)

Proof: Since the integral (18) converges absolutely, we can differentiate term by term in (18) with respect to ![]() as many times as we want and we obtain the first equality in (19). For the second equality we write (17) with

as many times as we want and we obtain the first equality in (19). For the second equality we write (17) with ![]() instead

instead ![]() and notice that the corresponding term in (17) still tends to zero as

and notice that the corresponding term in (17) still tends to zero as![]() . Then a formula similar to (18) is true with

. Then a formula similar to (18) is true with ![]() replaced by

replaced by![]() , hence the improper integral

, hence the improper integral ![]() converges absolutely and we obtain the second equality in (19).

converges absolutely and we obtain the second equality in (19).

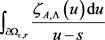

10. An Integral Formula for the Weierstrass ζ-Function

Weierstrass denoted the antiderivative of ![]() (which is defined up to an additive constant) by

(which is defined up to an additive constant) by![]() . Therefore

. Therefore ![]() and if we normalize it so that it is odd (see [1], page 273) we get

and if we normalize it so that it is odd (see [1], page 273) we get![]() . The series converges absolutely and uniformly on every compact set which does not contain any period point

. The series converges absolutely and uniformly on every compact set which does not contain any period point![]() . We obtain

. We obtain ![]() by integrating on any path that does not pass trough the poles the function

by integrating on any path that does not pass trough the poles the function ![]() from

from ![]() to z, where we can take

to z, where we can take ![]() such that

such that![]() . Then having in view (18) we can write:

. Then having in view (18) we can write:

![]() (20)

(20)

11. Conclusion

The concept of fundamental domain, as defined by Ahlfors (see [1], page 99), is crucial in understanding the geometry of the mappings by analytic functions. We realized that the Cauchy integral formula can be extended to the boundary of such a domain. However, this extension cannot be performed for an arbitrary analytic function and the process requires specific treatment for specific classes of such functions. We selected in this paper classes of functions we thought to be the most representative. The selection is far from exhaustive and a lot of work remains to be done.

Acknowledgements

We thank Aneta Costin for her support with technical matters.