The Effect of Gender Differences on the Choice of Banking Services ()

1. Introduction

Many service industries compete in the marketplace with relatively undifferentiated products. In order to maintain a competitive advantage, services need to improve their understanding of the wants and needs of different demographic groups and tailor the right value proposition to. Nevertheless, studies about the choice of banks based on their services have produced conflicting conclusions [1] . Some found no gender differences in the criteria used to select a bank [2] - [4] , while others established that some features such as costs were more important to men [5] - [7] , whereas women focused on other services [8] [9] . Assuming cost is an issue important to both genders. Banks often show their customers the costs for having an account in their bank either through comparative advertisements or third party publications (see Appendix A and Appendix B). For example, C. Bank illustrates the difference between the accrued costs for customers for having a checking account in different banks, emphasizing that there is a significant difference between their bank and other alternatives (see Appendix A). Given that the costs of having a checking account are not only the bank’s fixed charges but also include activity-based charges, customers pay additional fees when depositing or withdrawing their money. Similarly, W. Bank’s advertisement (see Appendix B) compares the costs associated with money transfers. These two examples provide all consumers with the factual information needed to make a rational decision that presumably fits their needs. In contrast, Appendix C and Appendix D present different arguments for the potential benefits of having a checking account, while both mention the benefits of the low costs and personal service of D. Bank (in the small letters). Appendix C’s example is directed to men and highlights a rational approach to decision making by indicating the growth potential of the account. The example in Appendix D, however, is directed at women and emphasizes personal attention and affective aspects of the bank’s services as opposed to stressing the arithmetic of the costs or focusing on the financial growth of the business.

These examples underscore an important dilemma for marketing managers in such service industries. Should they focus on a single area of their service such as low costs that benefits all customers or adopt a differentiated strategy that highlights different benefits for different gender segments? The answer to this question affects resource allocation and the effectiveness of the marketing strategy.

The purpose of this paper is to address this dilemma by providing a theoretical and empirical analysis of gender differences in choosing a financial service product such as a checking account. To resolve the conflicting results of previous studies, we use the evolutionary theory of men as hunters and women as gatherers to identify gender differences in the decision-making process with salient attributes leading to real choices rather than concentrating solely on the outcome or the order of importance of the factors when evaluating a single bank. We test our proposed approach using a descriptive field study in a choice context and an experimental study.

2. Theoretical Background

There are dozens of studies about the criteria people use to choose a bank. However, there are a limited number of comprehensive theories that explain the expected pattern of differences. Gender is often used as an easy segmentation tool, because marketing by gender is relatively simple, and the resulting segments are large enough to be profitable [10] . Using the evolutionary theory to explain the pattern of differences, we propose that men as hunters will focus on attributes such as costs, and women as gatherers who are more experientially and environmentally oriented, will focus on other aspects of the service such as the courtesy of the employees, and personal or professional service.

2.1. Psychological Differences between the Genders

The literature abounds with documented biological and sociological differences between men and women [11] . The most prominent and influential work is in the field of sociobiology, which attempts to explain all social behavior by evolution [12] . Studies have also explored the possible relationship between brain differences, sex hormones and behavior [13] . Supporters of this approach attribute gender differences to variations in work roles that evolved over millions of years, leading to changes in the brains of men and women [14] .

The evolutionary theory receives support from social psychology, which shows that women's self-image is based on the “self-in-relation” due to the importance they attach to the formation and maintenance of relationships [17] . In the same manner, men typically have an independent self-construal, whereas women typically have an interdependent self-construal [27] . Women also have a strong need for social interactions [28] . For example, within a formal online learning environment they send more interactive messages than men do and are more interested in all forms of assistance from others [29] . In the same manner, women are more likely than men to express concern about and responsibility for the well-being of others and less likely than men to support materialism and competition [30] . Recent biological evidence suggests an explanation for the notion of women as more communal by determining that the female hormone progesterone is negatively correlated to competitiveness [31] [32] .

2.2. Gender Differences in the Criteria for Selecting a Bank

[33] points out that gender segmentation has increased as marketers have recognized that women are a lucrative market. Specifically, they realize that decisions about financial services involve both men and women, and financial decisions are sometimes made as a couple [3] . Hence, understanding the differences between males and females about banking services is critical for the bank’s success [1] .

Earlier research presented conflicting findings regarding the differential importance of personal service as a bank selection criterion. Some researchers have found that women are more concerned about the friendliness of the staff (for example: tellers who smile, feeling at home in the bank, polite bank personnel) [8] [34] - [36] . However, other researchers have claimed that men are more concerned about personal attention and service for gaining recognition (personal contact with bank officers, one-on-one communication or contact branch manager and banking by phone) [33] [35] .

Similar conflicting results were found regarding convenience of the bank. Some research has showed that it is more important for women [1] [8] . Other researchers claimed it is more important for men [40] . Finally, some scholars have claimed that convenience is important for both: one stop banking and the ability to bank at any branch for men, and closeness to home or work place and parking facilities for women [35] .

The results with regard to the relative importance of the safety of one’s funds were also equivocal. [37] determined that this issue was more important for men, [34] found it was particularly important for women, and [38] claimed it was important for both. Similar conflicting results with regard to speedy and efficient service also emerged. Some research found it to be important for both men and women [37] [39] . [38] explained that this issue might be more important to women who still spent more time than men on childcare and were in a rush to finish their financial affairs and head home. Whereas [35] found that women only rated banks based on minimum waiting times, [40] claimed it was an important factor for men as well in choosing a bank.

In some studies, men were more concerned with service fees than women [5] - [7] . In others, women placed greater emphasis on financial benefits such as interest on saving accounts [8] [9] and prioritized channel saving and seeking value from credit card usage [40] . Finally, some scholars determined that costs such as minimum deposits or interest on loans were important factors for both men and women [39] [41] .

Overall, the empirical results of past research are equivocal regarding the importance of cost, speed of services and efficiency and the importance of personalized services (interaction and recognition) for men and women. Such conflicting findings leave us without a specific, clear direction in terms of the factors that are important for men vs. women in choosing a bank.

The contradictory findings might be a result of differences in the samples, time periods, and methods. Most studies in bank selection criteria have been conducted by asking the respondents to note what traits were important to them when choosing a bank (e.g., [37] [38] [42] - [44] ). Such direct questioning suffers from the flaws of social desirability; respondents might be unwilling or unable to report answers due to the desire to defend their ego or engage in impression management, resulting in data that are systematically biased toward the respondents’ perceptions of what is correct or socially acceptable. These issues may lead to unwarranted theoretical or practical conclusions regarding purchase motivations [45] .

The differential effect of gender on consumers’ evaluation of a single brand cannot capture the differences in real selection situations, when one needs to choose between alternative brands, a more realistic situation [46] . Therefore, as detailed in the method section, in the descriptive study, we adopt an indirect approach to assessing the saliency of the various attributes of different banks by querying the participants about their perceptions about real banks and asking them to choose one of them. Our main study explores whether in a real choice setting, consumers make choices in accordance with the evolutionary theory.

Based on the literature describing women as more relational and men as more instrumental, we posited that men would choose banks based on functional considerations such as fees, and women would be more concerned with experiential considerations such as personal service and the courtesy of the employees. Thus, we constructed two hypotheses that we tested for the first time in a situation where the respondents had to make a real choice about which bank to use.

H1―when choosing a bank, men will place greater emphasis on functional attributes such as costs than women will.

H2―when choosing a bank, women will place greater emphasis on experiential attributes such as personal service than men will.

3. Method

To test these hypotheses, we combined two methods: 1) a descriptive field study examined in a choice context and 2) an experimental study.

3.1. Descriptive Study

Our methodology uses a two-step approach. The first involves an exploratory study to determine the various service attributes consumers consider when choosing a bank. The second stage involves a descriptive research design that was conducted at two different levels. First, we determined how different five banks were one from one another at the aggregate level and which attributes contributed to this difference. Second, we conducted a data analysis at the group level based on gender differences.

3.1.1. Research Approach and Data

To identify the attributes that consumers would consider when choosing a bank for a checking account, we created a focus group with 30 participants (16 men, 14 women, all undergraduate students in management in an Israeli university). Table 1 presents the final set of attributes that were identified in the literature review [50] as well as attributes derived from the focus group.

Overall, the sample included 408 respondents selected through a stratified sampling procedure in a large Israeli city that allowed us to capture their heterogeneity with respect to their demographic characteristics. The sample contained 213 males and 195 females; 125 respondents had an income that fell below the national average, 115 were at the average level, and 168 had an above average income. With regard to education, 113 respondents were high school graduates, while 295 had a college degree. No differences were found between men and women with regard to demographics.

![]()

Table 1. identified attributes of banks.

In order to reduce the dimensionality of the data and avoid potential collinearity between similar service attributes due to high internal correlations, we conducted a principal component factor analysis. The results of this analysis yielded a three factor solution with the following concepts and percent of variance explained: 1) core bank services, 31.26%; 2) personal service, 20.49%, and 3) cost of service, 11.77%, with a total of 62.27% variance explained. The full analysis is presented in Appendix F. We used the factor scores of these three factors in the choice model [for further details about the use of factor scores in choice models, see [51] .

3.1.2. The Empirical Model

The multinomial logit (MNL) model is a simultaneous, compensatory, attribute choice model incorporating the concepts of thresholds, diminishing returns to scale, and saturation levels [47] . For each individual, the MNL estimates the probability of preferring each alternative in the choice set. Furthermore, the MNL is based on the assumption that the overall preference of a consumer for a particular choice, in this case, the preferred banking service, is a function of the perceived relative utility that the choice has for the consumer. The utility function can be separated into: 1) a deterministic component (measured in terms of the perceived value of the attributes of the alternative) and 2) a random error component, which is independent and identically distributed across all individuals with a Weibull distribution. In addition, it can provide diagnostic information regarding the salient attributes involved in the preference process.

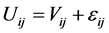

Let  be the utility of alternative product j for customer i, and J the number of alternative products. We can separate the utility function into a deterministic component

be the utility of alternative product j for customer i, and J the number of alternative products. We can separate the utility function into a deterministic component  (measured in terms of the perceived value associated with the characteristics of the products), and an unobserved random component,

(measured in terms of the perceived value associated with the characteristics of the products), and an unobserved random component,  , which is independent and identically distributed such that

, which is independent and identically distributed such that

(1)

(1)

where  is the deterministic component of utility of an individual i (

is the deterministic component of utility of an individual i ( ) when choosing alternative j (

) when choosing alternative j ( ) and

) and  is the random component of utility. Thus, the probability

is the random component of utility. Thus, the probability  that an alternative brand j will be chosen from a set of alternatives j depends only on the deterministic component of the utility function, such

that an alternative brand j will be chosen from a set of alternatives j depends only on the deterministic component of the utility function, such

that , and

, and

(2)

(2)

where ,

,  is the importance of the attribute kth in the utility, and

is the importance of the attribute kth in the utility, and

is the rating of consumer i of attribute k for alternative j.

3.1.3. Utility Specification

The deterministic component of the utility function has the following form:

(3)

(3)

where  refers to consumer i’s perceptions of the core services of bank j,

refers to consumer i’s perceptions of the core services of bank j,  refers to consumer i’s perceptions of the personal service of bank

refers to consumer i’s perceptions of the personal service of bank

j,  is consumer i’s perceptions of the cost associated with the services of bank j, and

is consumer i’s perceptions of the cost associated with the services of bank j, and ![]() are the parameters to estimate.

are the parameters to estimate.

3.2. Experimental Study

For further validation of the results obtained in the descriptive study, we conducted an online experiment using Prolific Academic site (https://www.prolific.ac) among Americans. One hundred and sixty-nine participants answered the questionnaires, 45% men and 55% women (in treatment one―49 men, 60 women; in treatment two―27 men, 33 women). The mean age was 32.14 years (SD = 10.36). With regard to marital status, 61% were single, 27% were married and 12% were in another status. Regarding gross annual income, 25% earned up to $10,000, 21% earned $10,001 - $25,000, 32% earned $25,001 - $50,000, 14% earned $50,001 - $100,000, 7% earned $100,001-$150,000 and 0.6% earned more than $150,000 a year. With regard to education, 40% had a high school education, 39% had a BA, 14% an MA, 4% a PhD and 4% had another kind of education. No differences were found between men and women demographically. A 2 (gender: men and women) by 2 (treatment one―high cost & low level of personal service/treatment two―low cost & high level of personal service) experiment was designed to investigate whether the likelihood of remaining with a bank would differ in the following two situations based on gender.

High cost and a low level of personal service. You have had your account in the same bank for the past couple of years. You are quite satisfied with the basic core services of your bank and with the personal service you receive from the employees and the manager when coming to the bank. But in comparison to other similar banks in your area, the waiting time for service and the commissions you are being charged are relatively high.

Low cost and a high level of personal service. You have had your account in the same bank for the past couple of years. You are quite satisfied with the basic core services of your bank and you are not satisfied with the personal service you receive from the employees and manager of the bank when coming to the bank. But in comparison to other similar banks in your area, the waiting time for service and the commissions you are being charged are low.

The respondents were asked to rate their likelihood of remaining with their current bank on a scale ranging from 1-not likely at all to 7-very likely. We asked the questions about demographics after the respondents indicated their responses to the two scenarios.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Study

Table 2 presents the estimates for the three attributes―core services, personal service and cost―in predicting the probability of choosing a particular bank.

![]()

Table 2. Estimates of aggregate and gender segmented models.

As the table illustrates, cost was significant only for men, supporting H1. Personal service was significant for both men and women, hence H2 was not confirmed. Finally, core services were important for both genders.

To determine whether the segmentation by gender was meaningful or whether the population was homogeneous, we followed Gensch’s suggestion [51] to examine possible segments by comparing the fit indices of the aggregate model to that of the segmented model using a log likelihood test: , where. The resulting χ² value of −15.6472 is distributed and significant at the 0.05 level, validating the appropriateness of this segmentation scheme.

4.2. Experimental Study

Differences in gender were significant only in scenario 1 where personal service was satisfactory, but the bank’s costs were high. In this situation, women were more likely than men to remain with the bank (Men: Mean = 4.12 SD = 1.83; Women: Mean = 4.77 SD = 1.407, sig = 0.046). In scenario 2 where personal service was unsatisfactory, but the bank’s costs were low, there was no difference between men and women in the decision to stay with the bank (Men: Mean = 2.63 SD = 1.08; Women: Mean = 3.21 SD = 1.59, N.S).

5. Discussion

In light of the conflicting and ambiguous findings regarding gender differences in the selection criteria of banks, the objective of this research was to examine differences between men and women when they had to actually choose a specific bank. Our findings provide some support for the predictions of the evolutionary theory that men as past hunters will be more focused on instrumental and practical attributes such as cost, and women as past gatherers are more contextual and include experiential attributes such as personal service in their considerations. One explanation for the similarity of the importance of personal service among men and women comes from Stafford’s findings [33] that men tend to place more value on personal recognition and attention (e.g., being catered to as important individuals who are knowledgeable and competent with respect to financial decision-making) than women. Personal service may include not only elements of relational or interpersonal communication, but also of ego gratification. Furthermore, as Berger and colleagues [52] noted, it “pays” to have friends. Given that executive bank appointments are tied to social ties; such personal service might serve as an instrumental utility. As Kahn & Kahn [53] maintained, impression management might influence men's purchases of a brand more than women's. Evolutionary theory explains this male tendency as a way to signal their financial resources to women and other potential male rivals [54] [55] . This explanation might clarify the importance of personal service for women as a relational experience and for men as an impression management technique.

6. Implications and Conclusions

These results add to our theoretical understanding of the role that gender plays in making choices that involve the consideration of a variety of factors. Our findings suggest that marketing managers of banks should not try to appeal to the aggregate market by emphasizing a single financial benefit for all customers. Instead, they would do well to target such appeal only for men and save ineffective resources when targeting also women (advertisement in Appendix A, Appendix B and Appendix C would be effective for targeting men only). Using an undifferentiated strategy for men and women will be effective when focusing on the core benefits of the service or on personal interactions with customers (presumably with a focus on different aspects of personal service for each gender). Moreover, targeting only women with appeals that highlight personal service (as presented in Appendix D) is not recommended, because this dimension is apparently equally important for both genders. Future research should further examine the personal service dimension in all its aspects to determine whether relational, interaction benefits are more important to women and attention and recognition are more important to men.

This study investigates a particular type of service. Future research can extend this approach into other service categories, such as visiting a restaurant or purchasing a cellular service, and to other financial services, such as credit card services, to determine whether there is a similar pattern of saliency. Doing so would strengthen the validity of our contention that evolutionary differences in men and women are the reason for the differences observed in the process of choosing a bank.

Appendix A

![]()

http://www.columbiabankonline.com/home/business/checking

Appendix B

![]()

https://transferwise.com/blog/2014-06/sir-richard-branson-joins-our-mission-to-stamp-out-hidden-fees/.

Appendix C

![]()

Appendix D

![]()

Appendix E. Questions on Bank Attributes

How would you rate the attributes below with regard to Bank L/P/D/M/B as you perceive them on a scale of 1 to 7, where 1 represents the lowest level of the attribute and 7 the highest.

Appendix F. Results of Factor Analysis

We categorized these factors into three groups that explained 63.277% of the variance in the responses.

![]()

Submit or recommend next manuscript to SCIRP and we will provide best service for you:

Accepting pre-submission inquiries through Email, Facebook, LinkedIn, Twitter, etc.

A wide selection of journals (inclusive of 9 subjects, more than 200 journals)

Providing 24-hour high-quality service

User-friendly online submission system

Fair and swift peer-review system

Efficient typesetting and proofreading procedure

Display of the result of downloads and visits, as well as the number of cited articles

Maximum dissemination of your research work

Submit your manuscript at: http://papersubmission.scirp.org/

Or contact jssm@scirp.org