Creative Digital Arts Education: Exploring Art, Human Ecology, and New Media Education through the Lens of Human Rights ()

1. Introduction

Human vulnerability in relation to food, ourselves, our lives, and our society at large is an issue that is affected by political, economic, social, and cultural components. Typical of postmodern theory, there are a variety of discourses on issues of power and food that are based on diverse values, beliefs and theories. [1] Brian S. Turner (2006), a sociologist, has argued that by analyzing our personal and societal/group vulnerabilities humankind will better understand, support and champion key issues of human rights. As cited by [2] the Centre for Triage Studies (2014), Turner believes that, “There is a foundation to human rights―namely our common vulnerability. Human beings experience pain and humiliation because they are vulnerable. While humans may not share a common culture, they are bound together by the risks and perturbations that arise from their vulnerability.”

Food is one of the basic elements of life and an important source of energy without which life is impossible to sustain. Yet, food has “… become a geopolitical weapon. It is not a new concept, but it is a potent one. … Food has been used as a means of persuasion, coercion or behavior control.” As a weapon of war or intentional military tactic, attackers prefer to besiege a town, city or in medieval times a castle as a way of starving out inhabitants. As discussed by [3] Van Schaack (2016) this strategy is still prevalent today despite international laws, conventions and resolutions to outlaw the use of starvation [4] (Mayer, 1984) as a means of declared or undeclared warfare. [5] McAuley (2015) further states that, “There are many crimes against humanity when it comes to power and control of the destiny of the human being…. But to use food as a means to alter lives, whether indiscriminately, deliberately or through simple omission is unconscionable. And yet, it still happens.” The Great Famine of Ireland (1840), [6] (Coogan, 2012), Ethiopia Famine (1983-1985), East Timor Famine (1977-1979), Holodomor and more recently Syria [7] (Ciezadlo, 2014) are just several examples of how food deprivation over time was and still is used as a deadly weapon ([8] (Riedel, Giacca, and Golay, 2014). One can observe that in our era, human rights issues are still precarious where political, governmental, and institutional protections remain fragile around the world. The Canadian government including the Canadian Museum for Human Rights (CMHR) that is located in Winnipeg, Manitoba recognizes five genocides ([9] Brean, 2014). They are as follows: Armenian (1915), Holodomor (1932-1933), Holocaust (WWII), Rwanda (1994) and the Bosnian (1992-1995).

When we specifically focus on the Holodomor, we can see that an act of genocide was committed against the Ukrainian people by Joseph Stalin’s Soviet Communist regime in 1932-1933. This orchestrated famine resulted in the death of millions of Ukrainians. This genocide in Ukraine is known as the Holodomor (killing or hunger by starvation). The government of Canada on May 29, 2008 passed Bill C-459 an [10] Act to establish the Ukrainian Famine and Genocide Holodomor Memorial Day (Statutes of Canada, 2008). As researchers we both have personal histories related to the events during the last century in Europe. One of us has few relatives left who survived Nazi concentration camps during World War Two. Another has a mother who is 90 years old, a Holodomor survivor, who has parents who are survivors of Nazi slave labour camps. What they experienced has not been forgotten, for it is still haunting them daily. Physical wounds have healed over time but the psychological and emotional scars are still present. We believe that addressing human rights issues is important for us personally, as well as for society at large. In this paper we will relate human rights issues to food specifically relating to issues of genocide, pollution, sustainability and aquafarming in pre-service education in a Canadian faculty of education (Image 1).

2. Human Rights in Relation to Human Ecology, Visual Arts and Visual Art Education

Recently [11] Cap, О., Delf-Timmerman, A., Doerksen, C., Normandeau, C., Smith, D., and Stark-Perreault, S., (2015) worked for the Manitoba Education and Advanced Learning Branch and replaced the former curriculum, titled Home Economics 7-9 with a new one called, [11] (Cap & al. 2015) Middle Years Human Ecology― Manitoba Curriculum Framework of Outcomes. Although not quite completed, the human ecology high school curriculum has an incorporation of the framework from the middle years document. Consequently, this new document framework provides ways to address the challenges and needs of human ecology for the next generation. The authors defined human ecology as a “holistic, multi-dimensional systems approach that empowers individuals to create thriving families and dynamic communities” (4). In their new grade 5-8 Manitoba curriculum document a number of essential foundations permeate the teaching and learning of human ecology. One of the seven essential foundational elements listed in the curriculum is coined, “sustainability”. Under the section Foods and Nutrition we find goal number six titled―Demonstrate understanding of sustainability. Under this heading three general learning outcomes provide one with a closer insight into what aspects should be explored in relation to foods, human rights and the environment. They are as follows: 6.1 explore food security and availability issues as they relate to food; 6.2 explore social justice and human rights issues as they relate to food; and 6.3 explore environmental matters as they relate to food. This new curriculum document offers teachers a roadmap on how to foster human rights awareness, sustainability and infuse it into the human ecology subject.

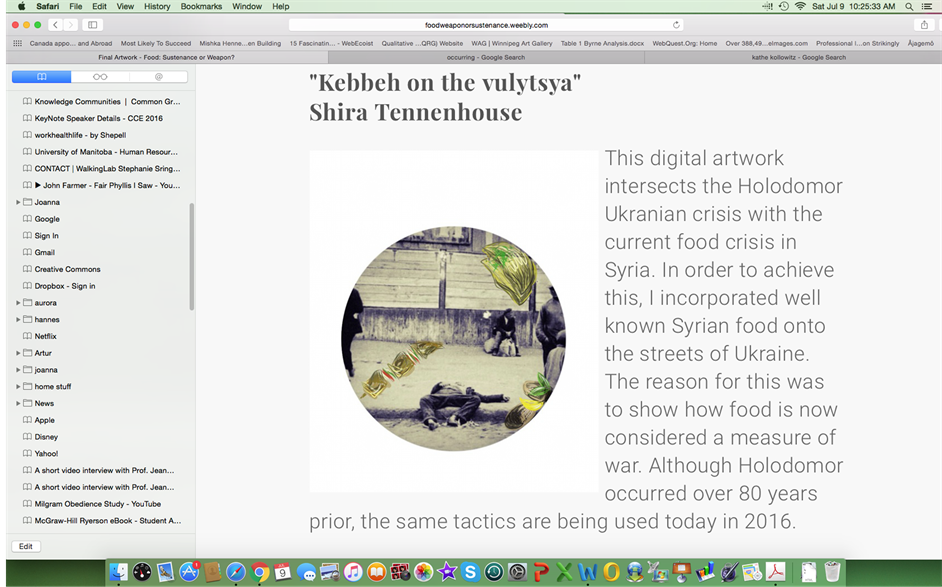

Image 1. Shira Tennhouse. digART work, [12] “Kebbeh on the Vulytsya” (2016). Artwork posted on a social media site using Weebly.

Human rights issues in visual art have a long history. Francisco Goya (1746-1828) is considered one of the first “modern” visual artists who actively addressed this theme, leaving lasting impressions on his viewers. With such works as The Third of May 1808, he depicted the tumultuous war torn world he experienced providing insightful, sensitive portrayals and analysis of human suffering ([13] Black and Cap 2014a; [14] Ozuna (2009). Following Goya, there have been many professional visual artists who have addressed human rights issues in their art for the last 250 years. In earlier journal articles [13] [15] Black and Cap (2014, a, b) provide overviews of these artists from the 18th century to today.

Food has been addressed by multitudes of professional artists: indeed the precedent is rich in examples. According to [16] Dolejšováv (2015) artists have delved into food art since the earliest of times delineating edibles in multifarious ways. Food has been depicted in every media with a focus on representation. Many artists employ the use of symbolism, and this is most notable in 17th Century Dutch trompe-l’œil (seemingly three- dimensional depictions) typically found in oil paintings like the work, Still Life by Willem Claesz in 1634 [17] Janson (1977). Like many artists in that era, Claesz was a Dutch Golden Age artist, who dealt with the “vanitas” theme: namely the idea of the passage of time leading to the belief of the insignificance and trifling nature of earthly possessions. Another playful and creative employment of food iconography was used by Giuseppe Arcimboldo 1526-1593 who cleverly created human portraits incorporating food imagery such as fruit and vegetables. [18] Steph (2016) delineates modern artists who have followed the representational/symbolic traditions today such as Jason Mecier and Song Dong. According to [16] Dolejšová (2016), artists have used food in art for a multitude of reasons ranging from the practical/aesthetic, and the autobiographical, to the conceptual and humorous. In recent years there has been a shift from the aesthetic to the political in which artists are dealing with such important food themes that currently effect us including issues of sustainability, factory farming, animal rights, environmental wreckage, and genetic food modifications (GMOs) ([19] Bae, 2013; [16] Dolejšováv, 2015; [20] McDermott and Reilly, 2015).

Human rights have been incorporated into visual arts education and this has become increasingly important in our volatile world. For an historical synopsis of art educators dealing with human rights issues also refer to articles by [13] [15] Black and Cap (2014 a, b). Notably, within the last few years there is an increasing call to action for art educators to address human rights issues in their art curricula ([20] McDermott and Reilly, 2015; [21] Rolling, 2016). [22] [23] The National Art Education Association in the United States (2014, 2016) has adopted the need to undertake issues of ethics, and enlighten citizenship in a global economy. [20] McDermott and Reilly (2015) argue that art educators should combat prevailing contemporary attitudes including disillusionment, disempowerment, helplessness, prejudice, and human submissiveness caused by current repressive political forces and global corporatization.

The development of school curricula pertaining to meaningful societal and ethical issues is increasing. Some art educators from kindergarten to higher education are addressing these concerns in different ways apparent in works such as (a) [24] Cornelius, Sherow, and Carpenter, (2010) who have written instructional resources on issues of the environment and sustainability; (b) [25] Fattal, (2006), who has developed community projects on Latino culture and food; and (c) [26] Halsey-Dutton, (2006) who has addressed teaching pre-service elementary educators issues-based instruction incorporating multilayered and meaningful societal issues. Indeed the approach to teaching human rights issues amongst art educators has apparent shared commonalities. Firstly, researchers often discuss the importance of including the study of contemporary artists who are dealing with human rights issues [24] Cornelius, Sherow, and Carpenter (2010); [16] Dolejšová (2016). Secondly, art educators discuss the significance of adapting an interdisciplinary focus [24] Cornelius, Sherow, and Carpenter, (2010). Finally, they strongly advise that a key approach to Human Rights Education (HRE) should include fostering student risk taking, development of learners’ critical thinking skills and nurturing creativity in the overall approach to teaching and learning ([16] Dolejšová, 2016; [20] Reilly, 2015; [26] Halsey-Dutton, 2016; [21] Rollings, 2016).

[27] The United Nations (1948) wrote The Universal Declaration of Human Rights providing the foundation of international laws. It is written in Article 25 that, “Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food…” We have addressed this key concept in our case study research regarding two courses for pre-service teachers in a faculty of education. In establishing the assignments dealing with human rights, we have incorporated the study of contemporary artists, using an interdisciplinary focus, asking our students to take risks, develop critical thinking skills, and approach their projects creatively within the development of artistic digital multimodal texts.

3. Case Study Research

The researchers investigated two courses lasting four months for pre-service teachers training to become high school educators at the Faculty of Education, University of Manitoba located in Canada. The first course was a Senior Year, Visual Arts Education course with an enrolment of 12 students, and the second one was a Senior Year, Human Ecology Education course with an enrolment of 11 students. There were 22 students involved in the research in total as one of the students was enrolled in both the Visual Art and Human Ecology Education classes. The courses extended for the winter term from January to March 2016. The primary inquiry that framed this study is “What are the benefits of using a human rights education approach to examining food as a theme in visual art and human ecology education?” To answer this question we asked student teacher participants to address this through the experience of creating contemporary multimodal digital texts.

Case study research was selected to study the complexities of the two classes. Participants were asked to experience new curricula in art education and human ecology education using digital technologies exploring human rights issues that pertain to food. This project is a two-fold process. During the first phase, students embarked on a “WebQuest Project”. During the second phase, mandatory for the visual art students only, they were engaged in a project entitled, “digiART and Power in the MisuUSe/USe of FOOD: A New Media, Arts Integrated Project.”

4. Description of the Students’ Processes

4.1. Human Ecology WebQuests

WebQuests were asked of students in order to integrate technology into inquiry based learning. We chose WebQuests because they enable students to engage in effective issues-based curricula development promoting students’ higher level thinking skills. WebQuests are designed so that people undertake research, engage in problem solving, critical thinking, and the making of creative digital texts. All the Human Ecology class and some of the visual art students created WebQuests working within groups or individually, with the plan that they could use these for their future students whom they will teach.

There are three processes involved in WebQuests design. Students become engaged in the first stage, Research and Idea Development, in which they gather data from the Internet, libraries and communities and shape their ideas for the WebQuest. In this stage our students examined key issues regarding their theme of food. During the second stage, Creating the WebQuest, students write the WebQuest. They followed the classic format which includes six components: (1) introduction, (2) task/outcomes, (3) process, (4) resources, (5) evaluation and (6) conclusion as delineated by [31] Bernie Dodge (2015), San Diego State University. The third stage is posting the materials to the Internet as a digital WebQuest for dissemination. Possible topics participants were given ranged from factory farming, food corporatization, starvation/genocide, GMOs (genetically modified food) to biopharming/molecular “pharming,” and food chemicalizations. There were many expectations for this WebQuest production: students were told that for this assignment they were expected to present it in class, and publish it online choosing one of such sites as Teacherweb.com, QuestGarden.com, Teachertube.com, and zunal.com. Moreover, we asked that the WebQuest should be produced so that another person could easily teach it, and in addition to this, it would be easily usable by future high school students for independent learning study.

4.2. Visual Art Education from WebQuests to digiART

Many of the visual art students created their WebQuests and they were told that they could connect this to their next assignment for the class: “digiART and Power in the MisuUSe/USe of FOOD.” This second digital assignment was mandatory for the visual art education students. This provided the opportunity for students to connect the WebQuest project with DigiART so that the research undertaken in the WebQuests was the beginning point for digiART project. To begin digiART we discussed many professional artists’ works regarding human rights issues from the past to the present particularly focusing on new media artworks like the Canadian artist, Jeff Wall, who produces ongoing large-scale back-lit cibachrome photographs, and the Iranian/American artist, Shireen Nishat who creates text/based visual artwork ranging from video to photographs.

Students were asked to experience the making of artworks that incorporate the visual with other forms of communications including written and audio texts. Since the advent of the Internet and our increasing reliance on the visual in our digital world [32] Duncum (2001) argues that visuals can no longer persist alone as we are barraged in contemporary society by multimodal texts [33] (Duncum, 2004). In digiART, students were taught about the works of Intermedia early Fluxus artist, Dick Higgins, during the 1960’s, who blurred boundaries between traditional and other communication modes. Students studied artistic multimodal texts for the last fifty-five years, thus stimulating ideas for their own new media art creation.

Learners engaged in preproduction, production, and postproduction processes producing final new media multimodal artworks. For this, they took part in a three-step process. Firstly, they gathered information, developing imagery in sketchbooks, worked out their ideas for the creation of the art and planned the artwork process during the preproduction process. Secondly, they engaged in learning about software and hardware in the making and completion of their digital artworks during the production process. Finally they displayed their completed artworks to the class and most importantly, to an international audience, as a result of posting their works to social media sites during the postproduction process. Sites included Blogger, Vimeo, WordPress, Google Website and others. The goals of this project are to: (1) enable students to experience their own creative new media works as it is believed that one cannot teach without actually having gone through the learning process oneself; (2) model new media curricula; (3) relate this experience to teaching future students; (4) foster an understanding of visual art/human ecology history, theory, appreciation, and production; (5) explore food in relation to a human rights theme; and (6) develop an appreciation of digital multimodal education. The results of digiART provided interactive, independent, creative art that can be shared with others in school communities from secondary level to higher education. We will discuss both the WebQuests and digiART projects in relation to the difficult yet important themes the students chose to tackle by providing a few examples.

5. Themes

5.1. Theme #1: Food and Insecurity/Genocide

Looking at issues of food insecurity and genocide, we will discuss one WebQuest and one digiART project. For both projects there is an interdisciplinary focus stemming from Human Ecology and Visual Art to history/social studies, and politics. Genocide and Food is a title of the first WebQuest. Three participants, [34] Crang, Persowich and Wins (2016) from the Human Ecology class designed this WebQuest for grades 11 and 12 students with interdisciplinary connections to history, politics/social studies, and nutrition. After explaining genocide and its origins, the WebQuest has information about mass killings as a result of starvation leading to deaths. For the secondary level readers the WebQuest writers provide numerous online resources about genocide, giving examples of the Holodomor and newcasts regarding starvation, in order for high school students to become knowledgeable about these issues. The steps the writers ask high school students to undertake are: gathering information about this topic; using this data for the creation of a poster; and finally, producing an artist statement about the image produced. On the WebQuest are resources regarding posters using effective persuasive messages. Designer of this WebQuest write that they planned it so that their students will learn about the history of genocide, explore its relation to food and starvation, find resources to expand their knowledge, and deal with questions that develop critical thinking and reasoning skills. An example of one of the pages of the WebQuest is below (Image 2).

In addition to this, instructions and resources are provided for teachers including an evaluation scheme for the poster in which marks are allocated for the artist statement, research, content organization, design and effort. The WebQuest designers write that their desired outcome is for students to gain knowledge regarding food used for war tactics and mass murder so that they can become aware of contemporary harmful food issues used for political manipulation and control.

On the same theme of starvation used for political gain, is the digiART work Food, Sustenance or Weapon?

Image 2. [34] Crang, Persowich and Wins’ WebQuest, Genocide and Food (2016). Introductory page posted on the social media, Questgarden.

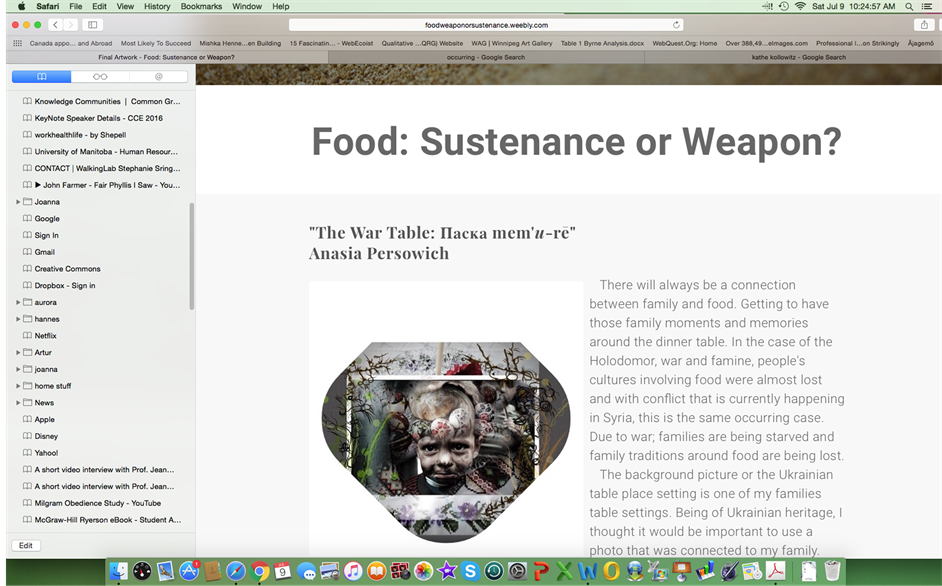

made by three participants in the Visual Art Class: [12] Guiliana Grande, Shira Tennenhouse, and Anasia Persowich (2016). The latter participant was also in the Human Ecology Class and had made the WebQuest described above before embarking on this artwork. As a result, she brought the knowledge she had acquired from the WebQuest development to this art project. For this art website, the three designers deal with issues of power using dictatorial war tactics used by those in political control to create mass starvation and extermination. To do this, they connect the Holodomor to the current issue of the food crisis occurring in Syria today. They point out past and present victims of war through the use of imagery. In the making of their own digital artworks, participants pay tribute to the American and European artists who have inspired their own artworks for this project including Käthe Kollwitz, Dorothea Lange, George Grosz and Otto Dix. They also outline processes used in the creation of their final artworks. These are shown on the social media site, Weebly in which the artists interrelate Syrian and Ukrainian subject matter. Below is the final work by Anasia.

In Image 3 appropriated imagery is combined with the artists’ own visuals she produced. The result is a digitally manipulated photograph. In Anasia’s research she discusses over 400,000 Syrians experiencing the ravages of war: malnutrition is her focus. To gather images Anasia looked at pictures from news sites, old fabrics and old family photographs. The artist states she uses symbolism to convey her ideas. She has placed an image of a refugee Syrian child starring grimly and directly at the viewer. Anasia includes barbwires to convey both obstacles and struggle. Behind the wire is green wheat symbolic of the food the child is deprived of but desperately needs. Ukrainian tablecloth imagery is visible that, as she states, is so important to Ukrainians, and to her own family gatherings. In her Weebly site, Anasia explains that through working on this project she has been given a model that will empower her future students to examine issues that are relevant and significant to today.

5.2. Theme #2: Environmental Destruction

The destruction of our environment is another human rights’ theme explored by the student, Sarah Paradise. Working alone in the Visual Art Education class, she explores the idea of environmental damage and devastation in both her WebQuest and digiART works―including a blog planned for grade 11 and 12 classes. We are discussing her work as one can view the connections between the WebQuest and digiART production. Both the

Image 3. The War Table by [12] Anasia Persowich, (2016). Artwork posted on a social media site using Weebly.

WebQuest and blog have similar titles: [35] [36] a, b). For these, she addresses the connections between food biodiversity, marine food ecosystems, and aquaculture using a cross-disciplinary approach combining visual art and human ecology with science (Image 4).

Sarah’s WebQuest is ambitious and extensive and needs to be reshaped, refined, and streamlined. Nevertheless, it does provide an example of a detailed plan of study that indicates her large-scale design and the type of WebQuest produced for this assignment by pre-service teachers. During the initial research stage, Sarah asks high school students to think about Marine food ecosystems and their healthy survival as they are constantly threatened by aquaculture. This includes food species forced to live in confined conditions, being threatened by viruses, and jeopardized by degrading and destructive environments. During the initial research stage, she plans for her high school students to watch key films such as [37] Salmon Confidential (2013) created by Twyla Roscovich and Alexandra Morton. This enables students to learn about and examine key scientific, political, and environmental concepts pertaining to food. Because she plans that politics and art merge for this mural project, Sarah draws upon art history, asking her secondary students to research mural makers and artists who worked with political themes such as Picasso and Banksy. Design principles including colour and symmetry are added into this extensive WebQuest. Finally, Sarah teaches art techniques such as stippling for the acrylic mural painting. With the research undertaken and imagery created, high school students move into the next stage: production, in which the completion of mural painting is outlined. For the final stage, they (1) display their murals, (2) create an artist statement, (3) write a personal reflection and (4) engage in a critique. Like the previous WebQuest discussed, Sarah has developed evaluations for teachers. One of the two evaluations is about the marking of the paintings. For this, she asks teachers to assess the following: students’ painting techniques, colour design theory, feedback and performance. Overall, Sarah indicates that this WebQuest will enable her future students to learn about the power of art to make people cognizant of the influence of individual ideas, the importance of addressing cultural and environmental issues, and the societal impacts our actions can have on the world.

After completing the WebQuest, Sarah moved into working on the DigiART project. For this, she produced a final digital artwork, a video, called [38] Invasive Species: Aqua-Virus (2016c). She decided to use new media as the digiART project was designed so that pre-service teachers create a digital production. Thus, instead of

Image 4. [25] Sarah Paradise, WebQuest, Breaking the Chains, Taking Action Against Aquaculture (2016). Artwork posted on a social media site, Questgarden.

producing a hands-on traditional mural painting (as she had planned for her students to produce in the WebQuest), she herself used another media as a mode of artistic communication: digital video. For the digiART project the theme remains the same as the one used for the WebQuest: namely, aquafarming and the impact of environmental food destruction. She posted this final video on a blogsite in which both process and final product are outlined. Additionally, she also posted curricula guidelines and software guides/tips (from clip cutting and recording, to embedding YouTube videos into Blogger). Finally, on this blog, tutorials are provided about the use of such programs as Final Cut Pro. Sarah posted this information in order to guide her future students, teachers, and the public at large about the way in which to make a similar video and share it with an international public. Consequently, she used the blogsite as a vehicle in which to teach and communicate the making of digital artworks using social media.

Experimental video is a nonnarrative, artistic approach to the moving image established by visual artists such as Fernand Léger close to a century ago [39] Bordwell and Thompson, (1997, 2004). This format of video production is the approach Sarah selected. She introduces her ideas through the title using bright, saturated colours and moving texts reminiscent of 1960s popular psychedelic imagery. The theme is about the ISA virus affecting salmon along the British Columbia coastline in Canada. Instrumental music that is comprised of two recordings is haunting, melancholy, and somber. Moving text is interplayed with visuals of salmon that are tagged, prodded, poked, sick and dying. Tainted water, ill fish, and people prodding the marine life are depicted along with texts about the imagery of salmon stricken with muscle inflammation and leukemia. This is a multimodal artwork complete with moving and still images, audio and text. [38] Sarah also posted her digiART process and product to other social media sites including YouTube (2016c) and her own personal WordPress website [40] Sarah Paradise (2016d). In her website, Sarah has included the digiART project which is an extension of her other works as a performance and digital artist.

Sarah explains her attitudes to her art making process using the third person point of view:

Sarah calls herself “Toxic Prophesy” and by doing so, she is voicing her prediction that our environment is being violated and degradated. She deals with ethical issues involving food pollution, environmental food conservation, and diverse political agendas of those in control. Through her art she provides a voice against the environmental destruction of food so vital to a healthy society. This is an excellent exemplar of work for future students to view.

6. Conclusion

Students are foraying into a new areas dealing with WebQuests and, for some, digital art. For participants such as Sarah, this is not a new mode of communication, for she is tech-savvy, having created new media for years and is experienced with social media evidenced in her postings across different Internet sites from YouTube, WordPress to Blogspot. In dealing with the theme of human rights, students have successfully incorporated five key approaches to this study that have been found successful in the past. On the subject of food they have employed an (1) interdisciplinary process; in which they took (2) risks; utilized (3) critical thinking skills; developed a (4) creative approach in order to produce (5) digital multimodal texts―the WebQuests and new media artworks. This was successful, enabling participants to experience WebQuests and digital art so that they in turn can create informative, thoughtful curricula using an effective pedagogical approach to the teaching of digital technologies in their future teaching at the high school level. Many students learned about the potential of working with digital technologies creatively. For instance [12] Anasia writes about her learning experience regarding the website she co-produced: “… I can see the endless possibilities and potential… there is for digital artwork in the classroom. By learning a different medium, in which I can express my thoughts and ideas, it gives me new information and tools that I can use… It was an interesting learning experience to develop so many new skills in digital media that can be used in my art making experience and be incorporated into my teaching activities” (2016).

Rather than shy away from topical, important and difficult human rights themes, we recommend that educators at the high school and higher education levels address them with all the benefits in mind. As a result of this study, we have found there are indeed many benefits for using the subject matter of human rights in the examination of food as a theme. Now that these participants have experienced this process, they can successfully model this same approach for their future students. Moreover, in producing new media art, the art education students underwent a thorough process of creating well-researched, rich, sophisticated, thoughtful and creative digital artworks. In addition to this, we have found that food is a strong human rights subject enabling students to tackle important issues of today in creative ways. Also, we have found that our approach enables students to address significant troubling issues in creative ways opening up opportunities for contemplating, reasoning, experiencing and creating, and by so doing, helping to empower learners so they feel less vulnerable and more capable. Finally, through asking our participants to post their digital works using social media it provides students an international voice concerning contemporary issues that they feel are wrong and unjust. [20] McDermott and Reilly (2015) argue that educators should resist current attitudes including disappointment, disempowerment, vulnerability, bias, and human compliance caused by societal exploitative and suppressive political and corporate powers. Teaching future teachers the way in which to address human rights issues from a hands-on, practical and theoretical, proactive stance is a way to resist and challenge the status quo. By doing so, we hope that this is a way for students to help create awareness, to feel empowered, and to become active in fighting for human rights issues, thus enabling positive change in our contemporary society and for the future.