1. Introduction

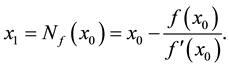

One of the most common iterative algorithms for finding solutions to an equation is Newton’s method. Given an equation  and an initial guess

and an initial guess , Newton’s method attempts to locate a better approximation,

, Newton’s method attempts to locate a better approximation,  , given by

, given by

Here, the numerical technique uses information about the first derivative of  at

at  to obtain an improved approximation

to obtain an improved approximation . The process then begins anew from

. The process then begins anew from , generating a sequence of numbers

, generating a sequence of numbers  intended to converge to a solution of the equation.

intended to converge to a solution of the equation.

Interestingly, though perhaps of little surprise to those familiar with iterative algorithms, numerical methods such as this have a tendency for failing in unpredictable manners. For example, applying Newton’s method to find the roots of  leads to an entire region of the complex plane for which initial seeds eventually bounce back and forth between

leads to an entire region of the complex plane for which initial seeds eventually bounce back and forth between ![]() and

and![]() , neither of which is a solution to

, neither of which is a solution to![]() . In this case,

. In this case, ![]() and

and ![]() lie on a super-attracting cycle of period two for the map

lie on a super-attracting cycle of period two for the map![]() . It is this failure of Newton’s method to converge on an open set of initial guesses that is investigated in this work.

. It is this failure of Newton’s method to converge on an open set of initial guesses that is investigated in this work.

The notion of studying the failure of Newton’s method applied to a complex polynomial dates back to the pioneering work of Curry, Garnett and Sullivan in 1983 [1] . Focusing on Newton’s method applied to a par- ticular family of cubic polynomials, the authors amazingly discover one of the most famous fractals of all, the Mandelbrot set, lurking throughout the parameter plane. Each parameter value in these special sets corresponds to a “bad” polynomial where Newton’s method fails on an open region in the complex plane due to the exis- tence of an extraneous attracting cycle distinct from the roots. Similar results in the case of a complex cubic were later obtained by Blanchard [2] , Head [3] , Lei [4] , Roberts and Horgan-Kobelski [5] (also verifying the phenomenon for Halley’s method), and Haeseler and Kriete [6] who applied quasiconformal surgery to prove the existence of rogue attractors for relaxed Newton’s method. The existence of Mandelbrot-like sets in the parameter plane and the connection with quadratic-like dynamics was thoroughly explained by Douady and Hubbard using their theory of polynomial-like mappings [7] .

In this work, we study Newton’s method applied to the complex quartic family

![]()

where ![]() is a complex parameter. The symmetric placement of the four roots is motivated by the nearest-root principle, the notion that initial seeds “typically” converge to the closest root. This is precisely the case for Newton’s method applied to a complex quadratic map with two distinct roots

is a complex parameter. The symmetric placement of the four roots is motivated by the nearest-root principle, the notion that initial seeds “typically” converge to the closest root. This is precisely the case for Newton’s method applied to a complex quadratic map with two distinct roots ![]() and

and![]() . The only points that fail to converge to either root under iteration lie on the perpendicular bisector

. The only points that fail to converge to either root under iteration lie on the perpendicular bisector ![]() of the segment joining

of the segment joining ![]() and

and![]() . These initial seeds cannot decide which root to converge toward and consequently, remain on

. These initial seeds cannot decide which root to converge toward and consequently, remain on ![]() for all time. For any other initial guess

for all time. For any other initial guess![]() , Newton’s method converges to the root located on the same side of

, Newton’s method converges to the root located on the same side of ![]() as

as![]() . In general, the invariance of

. In general, the invariance of ![]() occurs whenever there is a line of symmetry amid the configuration of roots. For the family

occurs whenever there is a line of symmetry amid the configuration of roots. For the family![]() , the real axis is a line of symmetry and is therefore invariant under Newton’s method. This will play a key role in studying the dynamics as it allows for a reduction to a map of one real variable.

, the real axis is a line of symmetry and is therefore invariant under Newton’s method. This will play a key role in studying the dynamics as it allows for a reduction to a map of one real variable.

The primary difference between the cubic and quartic cases is the number of “free” critical points. In addition to the roots of a polynomial, its inflection points also turn out to be critical points of the Newton map. Unlike the fixed roots, these points can iterate freely around the complex plane. There is only one such point for a cubic map, but two free critical points for the quartic case since the second derivative is quadratic. Not surprisingly, due to the identical numbers of critical points, our problem turns out to have many similarities with the general complex cubic. In [8] , Milnor classifies the types of hyperbolic components possible in the parameter plane for the general cubic, obtaining fractal-like figures such as Mandelbrot-like sets and tricorns as well as swallow and product configurations. The distinguishing element between these fractal-like sets is the type and behavior of the critical points. Following Milnor’s work, we are able to locate and explain the existence of these same types of fractals in the parameter plane for Newton’s method applied to![]() .

.

The main tool in our analysis is the reduction to a map in one real variable. This occurs in the cases where ![]() is real or purely imaginary due to the invariance and symmetry described above. We apply standard arguments from real dynamical systems theory to prove that there are no extraneous attracting cycles in the case

is real or purely imaginary due to the invariance and symmetry described above. We apply standard arguments from real dynamical systems theory to prove that there are no extraneous attracting cycles in the case![]() . Using a bisection algorithm, we numerically locate an abundance of values

. Using a bisection algorithm, we numerically locate an abundance of values ![]() such that Newton’s method applied to

such that Newton’s method applied to ![]() contains a super-attracting

contains a super-attracting ![]() -cycle. Bifurcations are explored as

-cycle. Bifurcations are explored as ![]() varies. Whether the free critical points lie on the same or distinct periodic cycles for these special parameter values has important consequences for the resulting figures in the

varies. Whether the free critical points lie on the same or distinct periodic cycles for these special parameter values has important consequences for the resulting figures in the ![]() -parameter plane.

-parameter plane.

2 Newton’s Method and Complex Dynamics

Let ![]() denote the

denote the ![]() -fold composition of

-fold composition of ![]() with itself. Given some

with itself. Given some![]() , we define the orbit of

, we define the orbit of ![]()

to be the sequence of points ![]() where

where![]() . We refer to

. We refer to ![]() as the initial seed of the orbit.

as the initial seed of the orbit.

A point ![]() is said to be a periodic point if

is said to be a periodic point if ![]() for some

for some![]() , and the smallest such

, and the smallest such ![]() is known as the period of

is known as the period of![]() . In this case, we say that

. In this case, we say that ![]() lies on an

lies on an ![]() -cycle or periodic orbit of period

-cycle or periodic orbit of period![]() . A periodic point of Period 1 is known as a fixed point.

. A periodic point of Period 1 is known as a fixed point.

A periodic point ![]() with period

with period ![]() is said to be attracting if

is said to be attracting if ![]() and repelling if

and repelling if![]() . It is straight-forward to show that seeds in a sufficiently small neighborhood of an attracting

. It is straight-forward to show that seeds in a sufficiently small neighborhood of an attracting

periodic orbit are attracted to that orbit under iteration. A periodic point ![]() with period

with period ![]() is said to be

is said to be

neutral if![]() . Finally, a periodic point

. Finally, a periodic point ![]() satisfying

satisfying ![]() is called super-attracting, a

is called super-attracting, a

title that corresponds to the rate at which nearby points converge.

Definition 1 Suppose that ![]() is an attracting periodic orbit of period

is an attracting periodic orbit of period![]() . Then the open set

. Then the open set ![]() containing all points

containing all points ![]() such that

such that![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() converges to some periodic point in

converges to some periodic point in ![]() is called the basin of attraction for

is called the basin of attraction for![]() .

.

We now restrict our attention to studying Newton’s method applied to a complex polynomial![]() . For a fixed

. For a fixed![]() , this produces a rational map of the extended complex plane

, this produces a rational map of the extended complex plane ![]() denoted

denoted ![]() and given by

and given by

![]()

Studying the convergence of Newton’s method is equivalent to investigating the orbits of initial seeds under iteration of the map![]() , placing our study squarely in the field of complex dynamical systems.

, placing our study squarely in the field of complex dynamical systems.

There are two complimentary sets used to describe the dynamics of a map in complex dynamics, the Julia set, where the interesting and chaotic behavior occurs, and its tame cousin, the Fatou set, where attracting periodic cycles and their basins of attraction lie. The Julia set for a rational map is the closure of the set of repelling periodic points [9] . This is an invariant, perfect and fractal-like set displaying sensitive dependence on initial conditions. Any neighborhood of a point in the Julia set is mapped under iteration to cover all of the extended complex plane except at most two points. For Newton’s method, this implies that arbitrarily close to any point in the Julia set are seeds that will iterate to each root of![]() . Thus, choosing an initial seed in the Julia set of

. Thus, choosing an initial seed in the Julia set of ![]() is not a major difficulty since a small perturbation will ensure convergence toward a root.

is not a major difficulty since a small perturbation will ensure convergence toward a root.

The roots of ![]() and their basins of attraction are in the Fatou set. It is easy to see that if

and their basins of attraction are in the Fatou set. It is easy to see that if![]() , then

, then![]() , so that the root

, so that the root ![]() is a fixed point of the dynamical system

is a fixed point of the dynamical system![]() . Moreover, a short calculation gives

. Moreover, a short calculation gives

![]() (1.1)

(1.1)

If ![]() is a simple root of

is a simple root of![]() , then it follows that

, then it follows that ![]() and thus

and thus ![]() is a super-attracting fixed point. This is certainly a good property for a numerical root-finding algorithm to possess as it implies that nearby points are strongly attracted towards a root of the polynomial. However, equation (1.1) is significant for another reason, for it indicates that inflection points of

is a super-attracting fixed point. This is certainly a good property for a numerical root-finding algorithm to possess as it implies that nearby points are strongly attracted towards a root of the polynomial. However, equation (1.1) is significant for another reason, for it indicates that inflection points of ![]() are also critical points of

are also critical points of![]() . Since these inflection points are typically not roots of

. Since these inflection points are typically not roots of ![]() (and thus not fixed), we will refer to them as the free critical points of

(and thus not fixed), we will refer to them as the free critical points of![]() . In complex dynamics, it is the orbit of the critical point that governs the behavior of the underlying dynamics. In particular, we have the following important theorem of Fatou and Julia (see [9] [10] ) for rational maps on

. In complex dynamics, it is the orbit of the critical point that governs the behavior of the underlying dynamics. In particular, we have the following important theorem of Fatou and Julia (see [9] [10] ) for rational maps on![]() :

:

Theorem 1 Every attracting cycle of a rational map attracts at least one critical point.

In the case of Newton’s method, the critical points corresponding to roots are themselves attractors. Ge- nerically, we also expect the free critical points to be attracted towards the roots. However, an intriguing situation occurs when one or more of the free critical points converges to an extraneous attracting cycle, that is, a cycle distinct from one of the roots of the polynomial. The basin of attraction for such a cycle is an entire region in ![]() for which initial seeds never converge to a root. In this case, the roots elude detection, for a small perturbation of a failing initial seed may not lead to convergence to one of the roots. The dynamical plane for such an example is displayed in Figure 1. These “bad’’ polynomials, with elusive zeros and extraneous at- tracting cycles, are the main focus of this paper.

for which initial seeds never converge to a root. In this case, the roots elude detection, for a small perturbation of a failing initial seed may not lead to convergence to one of the roots. The dynamical plane for such an example is displayed in Figure 1. These “bad’’ polynomials, with elusive zeros and extraneous at- tracting cycles, are the main focus of this paper.

![]()

Figure 1. The dynamical plane for Newton’s method applied to ![]() with

with![]() . Initial seeds are colored according to the root they converge to. Points col- ored black iterate toward a super-attracting period 2-cycle.

. Initial seeds are colored according to the root they converge to. Points col- ored black iterate toward a super-attracting period 2-cycle.

3. A Symmetric Fourth-Degree Family of Polynomials

We now restrict our investigation to applying Newton’s method to the family of fourth degree polynomials defined by

![]()

where ![]() is a complex parameter. This family was briefly considered by Sutherland at the end of his doctoral thesis [11] . By expanding

is a complex parameter. This family was briefly considered by Sutherland at the end of his doctoral thesis [11] . By expanding![]() , we find that

, we find that

![]() (1.2)

(1.2)

and thus ![]() always has real coefficients.

always has real coefficients.

For the remainder of this work, we will denote ![]() as the complex rational map obtained by applying New- ton’s method to

as the complex rational map obtained by applying New- ton’s method to![]() . The free critical points for

. The free critical points for![]() , arising as the inflection points of

, arising as the inflection points of![]() , are given by

, are given by

![]() (1.3)

(1.3)

Note that by Theorem 1, there can be at most two distinct extraneous attracting cycles. If we let![]() ,

,

then the discriminant ![]() in Equation (1.3) simplifies to

in Equation (1.3) simplifies to

![]()

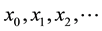

The equation ![]() defines a hyperbola in the

defines a hyperbola in the ![]() -parameter plane and serves as an important boundary to the possible types of free critical points

-parameter plane and serves as an important boundary to the possible types of free critical points ![]() described below and in Figure 2:

described below and in Figure 2:

• ![]() two real free critical points equidistant from

two real free critical points equidistant from![]() ,

,

![]()

Figure 2. The hyperbola that distinguishes the ![]() -para- meter plane in terms of the critical points of

-para- meter plane in terms of the critical points of![]() . Within the curves, the two free critical points are real, while outside, they form a complex conjugate pair.

. Within the curves, the two free critical points are real, while outside, they form a complex conjugate pair.

• ![]() single real (repeated) free critical point at

single real (repeated) free critical point at![]() ,

,

• ![]() two free critical points as a complex conjugate pair with real part

two free critical points as a complex conjugate pair with real part![]() .

.

Using equation (1.2), we compute directly that

![]() (1.4)

(1.4)

While this rational map may appear imposing, it possesses certain symmetries under conjugacy that signi- ficantly reduce the size of the ![]() -parameter plane.

-parameter plane.

Lemma 1 For any![]() ,

,

i) the real axis is invariant under![]() ,

,

ii)![]() , and

, and

iii)![]() is topologically conjugate to

is topologically conjugate to ![]() via the conjugacy

via the conjugacy![]() .

.

Proof Since ![]() is a polynomial with real coefficients, so is its derivative. This leads to all coefficients in

is a polynomial with real coefficients, so is its derivative. This leads to all coefficients in ![]() being real and the invariance of the real axis. To prove item (ii), note that

being real and the invariance of the real axis. To prove item (ii), note that![]() , since the roots of

, since the roots of ![]() are left unchanged when

are left unchanged when ![]() is replaced by

is replaced by![]() . It follows that

. It follows that ![]() by definition. Finally, item (iii) follows from Equation (1.4) by verifying that

by definition. Finally, item (iii) follows from Equation (1.4) by verifying that

![]()

as desired. ![]()

Since attracting cycles are preserved under conjugacy, the symmetries described in items (ii) and (iii) above enable us to restrict the parameter plane to the region ![]() Being only con- cerned with those

Being only con- cerned with those ![]() -values for which

-values for which ![]() possesses an extraneous attracting orbit, it suffices to follow the orbit of the free critical points for

possesses an extraneous attracting orbit, it suffices to follow the orbit of the free critical points for![]() . There is an important additional symmetry when

. There is an important additional symmetry when ![]() is purely ima- ginary, as indicated by the following lemma.

is purely ima- ginary, as indicated by the following lemma.

Lemma 2 ![]() is conjugate to

is conjugate to ![]() via the conjugacy

via the conjugacy![]() .

.

Proof It is straight-forward to show that two systems arising from Newton’s method applied to polynomials whose roots differ by an affine map, are topologically conjugate (see [5] for example). Since ![]() is an affine map and a bijection between the roots of

is an affine map and a bijection between the roots of ![]() and the roots of

and the roots of![]() , the result follows. Alternatively, direct

, the result follows. Alternatively, direct

substitution into Equation (1.4) shows that![]() .

. ![]()

3.1. The Case ![]() Real

Real

Restricting to the case ![]() leads to some nice reductions that allow for a complete classification of the orbits of the free critical points. We will show that the orbits of

leads to some nice reductions that allow for a complete classification of the orbits of the free critical points. We will show that the orbits of ![]() converge to one of the roots of

converge to one of the roots of ![]() and con- sequently, there are no extraneous attracting cycles for

and con- sequently, there are no extraneous attracting cycles for ![]() when

when ![]() is real.

is real.

For![]() ,

, ![]() now contains the repeated root

now contains the repeated root ![]() in addition to the roots

in addition to the roots ![]() and

and![]() . Because

. Because ![]() is a repeated root, it is not super-attracting in this case. The Newton map simplifies to

is a repeated root, it is not super-attracting in this case. The Newton map simplifies to

![]()

Since the free critical points are real for![]() , we restrict the domain of the Newton map to the real axis, hence the use of the variable

, we restrict the domain of the Newton map to the real axis, hence the use of the variable ![]() as opposed to

as opposed to![]() . The free critical points are

. The free critical points are

![]()

and the two poles of![]() , denoted

, denoted ![]() and

and![]() , are given by

, are given by

![]()

For later use, we have

![]() (1.5)

(1.5)

Theorem 2 For all![]() , the orbits of the two free critical points under

, the orbits of the two free critical points under ![]() always converge to roots of

always converge to roots of![]() . Specifically, we distinguish the following two cases:

. Specifically, we distinguish the following two cases:

1) For ![]() for all

for all![]() .

.

2) For ![]() and

and![]() .

.

Proof Due to item (iii) of Lemma 1, it suffices to consider the case![]() . We begin with the case

. We begin with the case![]() , where a series of straight-forward estimates show that the critical points, poles and roots of

, where a series of straight-forward estimates show that the critical points, poles and roots of ![]() are arranged in the following manner:

are arranged in the following manner:

![]() (1.6)

(1.6)

Next, using

![]()

and the ordering described in inequality (1.6), we see that ![]() while

while![]() . Moreover, it fol- lows from equation (1.5) that

. Moreover, it fol- lows from equation (1.5) that ![]() is strictly increasing on the open interval

is strictly increasing on the open interval ![]() and that

and that![]() . Thus, for

. Thus, for![]() , we have

, we have ![]() while for

while for![]() , we have

, we have ![]() (see Figure 3).

(see Figure 3).

It follows that for![]() , the orbit of

, the orbit of ![]() under

under ![]() is a strictly increasing sequence bounded above by the fixed point

is a strictly increasing sequence bounded above by the fixed point ![]() and for

and for![]() , the orbit of

, the orbit of ![]() is a strictly decreasing sequence bounded below by the fixed point

is a strictly decreasing sequence bounded below by the fixed point![]() . Since the only other fixed points for

. Since the only other fixed points for ![]() are

are ![]() and

and![]() , standard arguments using the con- tinuity of

, standard arguments using the con- tinuity of ![]() on

on ![]() show that all points in

show that all points in ![]() converge to the attracting fixed point at

converge to the attracting fixed point at![]() .

.

For the case![]() , the Newton map reduces even further since

, the Newton map reduces even further since ![]() has the root

has the root ![]() with multiplicity three in addition to the simple root

with multiplicity three in addition to the simple root![]() . In this case,

. In this case, ![]() becomes

becomes ![]() and

and ![]() while

while![]() . The pole

. The pole ![]() vanishes and

vanishes and![]() . Here, the free critical point

. Here, the free critical point ![]() has been transformed into an attracting fixed point with derivative

has been transformed into an attracting fixed point with derivative![]() . A simple web-diagram of

. A simple web-diagram of ![]() shows that the orbit of

shows that the orbit of ![]() converges to the repeated root at

converges to the repeated root at![]() .

.

To prove the rest of item (ii), we compute that for![]() ,

,

![]()

while for![]() ,

,

![]()

At![]() , we have

, we have ![]() (super-attracting fixed point). The major change between these two inequalities and inequality (1.6) is that the two roots

(super-attracting fixed point). The major change between these two inequalities and inequality (1.6) is that the two roots ![]() and 1 have interchanged positions. For

and 1 have interchanged positions. For![]() , the super-attract- ing fixed point 1 lies between the two poles, while for

, the super-attract- ing fixed point 1 lies between the two poles, while for![]() , it is the super-attracting fixed point at

, it is the super-attracting fixed point at ![]() that is located between the two poles. In addition, the critical point

that is located between the two poles. In addition, the critical point ![]() jumps to the other side of the pole

jumps to the other side of the pole![]() , be- coming a local min instead of a local max (see Figure 4). However, the dynamical behavior of the critical points is unchanged. Similar arguments as with case (i) show that the orbit of

, be- coming a local min instead of a local max (see Figure 4). However, the dynamical behavior of the critical points is unchanged. Similar arguments as with case (i) show that the orbit of ![]() monotonically increases as it converges to

monotonically increases as it converges to ![]() for

for![]() . The orbit of

. The orbit of ![]() monotonically increases as it converges to 1 for

monotonically increases as it converges to 1 for ![]() and monotonically decreases to 1 for

and monotonically decreases to 1 for![]() . As before, the continuity of

. As before, the continuity of ![]() on the appropriate intervals in addition to the number and location of the fixed points allows us to prove these convergence results.

on the appropriate intervals in addition to the number and location of the fixed points allows us to prove these convergence results. ![]()

3.2. The Case ![]() Pure Imaginary

Pure Imaginary

Due to Theorem 2, the interesting Newton maps occur when ![]() becomes complex. However, the reduction to a real map in the previous subsection suggests a practical approach to investigating the case where

becomes complex. However, the reduction to a real map in the previous subsection suggests a practical approach to investigating the case where ![]() is purely imaginary.

is purely imaginary.

Consider the case ![]() with

with![]() . By Lemma 2, we can restrict to the regime

. By Lemma 2, we can restrict to the regime![]() . For ease of notation, we let

. For ease of notation, we let ![]() correspond to Newton’s method applied to

correspond to Newton’s method applied to![]() . In this case, the roots lie on the vertices of a rhombus in the complex plane. Based on previous work applying Newton’s method to cubics [1] [2] [5], the symmetry of this configuration suggests that Newton’s method may fail badly for certain

. In this case, the roots lie on the vertices of a rhombus in the complex plane. Based on previous work applying Newton’s method to cubics [1] [2] [5], the symmetry of this configuration suggests that Newton’s method may fail badly for certain ![]() -values. We shall see that this is indeed the case. The driving force behind the interesting dynamics is that initial seeds on the real-

-values. We shall see that this is indeed the case. The driving force behind the interesting dynamics is that initial seeds on the real-

axis are equidistant from the two imaginary roots. If these seeds are far enough away from the roots at ![]() and

and![]() , their orbits bounce around the real axis, unable to converge to a root.

, their orbits bounce around the real axis, unable to converge to a root.

For the special case![]() , the roots of

, the roots of ![]() are the four roots of unity and as a result of this symmetry, the only “free” critical point is

are the four roots of unity and as a result of this symmetry, the only “free” critical point is ![]() of multiplicity two. However,

of multiplicity two. However, ![]() is also a pole for the Newton map and therefore iterates to

is also a pole for the Newton map and therefore iterates to ![]() which is a repelling fixed point. Thus, there can be no extraneous attracting cycles for the case

which is a repelling fixed point. Thus, there can be no extraneous attracting cycles for the case![]() .

.

For![]() , the critical points of

, the critical points of ![]() are real and given by

are real and given by

![]()

Due to the invariance of the real axis under our Newton map, this implies that any extraneous attracting cycle must lie on the real axis. As with the case![]() , this allows us to restrict our study to a rational map

, this allows us to restrict our study to a rational map ![]() of one real variable,

of one real variable,

![]()

Of particular importance is the fact that ![]() is an odd function whose critical points are symmetric about the origin. If the orbit of

is an odd function whose critical points are symmetric about the origin. If the orbit of ![]() lies on or converges to an attracting

lies on or converges to an attracting ![]() -cycle, then so will its partner

-cycle, then so will its partner![]() . However, it may be the case that

. However, it may be the case that ![]() and

and ![]() lie on or converge to the same attracting orbit, a phenomenon that will be critical to understanding the larger parameter plane picture.

lie on or converge to the same attracting orbit, a phenomenon that will be critical to understanding the larger parameter plane picture.

The poles of ![]() are

are ![]() and

and![]() , where

, where![]() . Using some basic estimates for the regime

. Using some basic estimates for the regime![]() , we have

, we have

![]()

Moreover, for![]() ,

, ![]() is concave down with a local maximum at

is concave down with a local maximum at ![]() and

and![]() . For

. For![]() ,

, ![]() is concave up with a local minimum at the super-attracting fixed point

is concave up with a local minimum at the super-attracting fixed point![]() . It follows that each

. It follows that each ![]() converges to the root

converges to the root ![]() under iteration of

under iteration of![]() . Since

. Since ![]() is odd, we also have that each

is odd, we also have that each ![]() con- verges to the root

con- verges to the root![]() . Thus, the interesting dynamics of

. Thus, the interesting dynamics of ![]() occurs between the poles

occurs between the poles ![]() and

and![]() .

.

The following lemma captures some key information about the behavior of the critical points as ![]() varies.

varies.

Lemma 3 For![]() , the orbits of the free critical points

, the orbits of the free critical points ![]() converge to the roots

converge to the roots ![]() or

or![]() . Spe- cifically, we have the following:

. Spe- cifically, we have the following:

(i) For![]() ,

, ![]() is strictly decreasing with respect to

is strictly decreasing with respect to![]() , while

, while ![]() is strictly increasing with respect to

is strictly increasing with respect to![]() .

.

(ii) For![]() ,

, ![]() and

and![]() .

.

(iii) For![]() ,

, ![]() converges to

converges to ![]() while

while ![]() converges to

converges to ![]() under iteration of

under iteration of![]() .

.

Proof Since ![]() is an odd function and

is an odd function and![]() , we see that

, we see that![]() . Thus, to prove item (i), it suffices to show that

. Thus, to prove item (i), it suffices to show that ![]() is decreasing with respect to

is decreasing with respect to![]() . We first compute

. We first compute

![]()

where![]() . Taking the derivative of

. Taking the derivative of ![]() with respect to

with respect to ![]() and simplifying the numerator gives

and simplifying the numerator gives

![]()

which is clearly negative, proving that ![]() is decreasing with respect to

is decreasing with respect to![]() .

.

To prove item (ii), letting![]() , we see that

, we see that![]() . Using part (i), it follows that for

. Using part (i), it follows that for![]() ,

,![]() . The second inequality follows since

. The second inequality follows since ![]() is odd.

is odd.

Item (iii) follows easily from (ii) and the fact that all points in ![]() converge to

converge to ![]() under iteration while all points in

under iteration while all points in ![]() converge to

converge to![]() .

. ![]()

Our goal is to search for attracting cycles of ![]() distinct from roots when

distinct from roots when![]() . While it is difficult to make precise calculations locating specific examples, there are three values worthy of mention.

. While it is difficult to make precise calculations locating specific examples, there are three values worthy of mention.

• For![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() lie on the same super-attracting 2-cycle.

lie on the same super-attracting 2-cycle.

•![]() ,

,

has ![]() and

and ![]() lying on distinct super-attracting 2-cycles.

lying on distinct super-attracting 2-cycles.

• For![]() .

.

The first value is derived by solving the equation ![]() for

for![]() . Since

. Since ![]() is odd, it follows that

is odd, it follows that ![]() and thus the free critical points lie on the same super-attracting 2-cycle (see Figure 5). The calculation shows that this is the only

and thus the free critical points lie on the same super-attracting 2-cycle (see Figure 5). The calculation shows that this is the only ![]() -value in

-value in ![]() with this property. By Lemma 2, the same phenomenon occurs for

with this property. By Lemma 2, the same phenomenon occurs for![]() . We note that the constant

. We note that the constant ![]() agrees with the value given in Exercise 10, Chapter 13 of Devaney’s undergraduate textbook [12] . The second value,

agrees with the value given in Exercise 10, Chapter 13 of Devaney’s undergraduate textbook [12] . The second value, ![]() , is found by solving

, is found by solving ![]() for

for![]() . This leads to an even eighth-degree polynomial that can be solved using Ferrari’s formula for a quartic equation (calculated using Maple [13] ). It is the only new solution (other than its reciprocal

. This leads to an even eighth-degree polynomial that can be solved using Ferrari’s formula for a quartic equation (calculated using Maple [13] ). It is the only new solution (other than its reciprocal![]() .) Thus,

.) Thus, ![]() and

and ![]() are the only parameter values in

are the only parameter values in ![]() for which the critical points are pe- riodic of period two. The value

for which the critical points are pe- riodic of period two. The value ![]() is significant in that it defines a regime

is significant in that it defines a regime ![]() with more com- plicated dynamics for the free critical points. This will be apparent in some of our numerical investigations.

with more com- plicated dynamics for the free critical points. This will be apparent in some of our numerical investigations.

Due to the challenges of studying higher iterations of ![]() analytically, a computer program was written in C++ to locate super-attracting periodic points numerically. For a fixed period

analytically, a computer program was written in C++ to locate super-attracting periodic points numerically. For a fixed period![]() , the program commences with

, the program commences with![]() , which is slightly greater than our upper bound of

, which is slightly greater than our upper bound of![]() . Using a bisection method, solutions to the equation

. Using a bisection method, solutions to the equation ![]() are located as

are located as ![]() decreases. (Using Newton’s method to investigate Newton’s method was a bit too paradoxical for us!) The values located, shown in Table 1 up to

decreases. (Using Newton’s method to investigate Newton’s method was a bit too paradoxical for us!) The values located, shown in Table 1 up to![]() , are

, are ![]() -values where the free critical points lie on super-attracting periodic cycles. Thus, Newton’s method for these cases will fail on an open set of initial conditions in the complex plane. As the period

-values where the free critical points lie on super-attracting periodic cycles. Thus, Newton’s method for these cases will fail on an open set of initial conditions in the complex plane. As the period ![]() increases, the number of periodic orbits increases exponentially. Letting the program run exhaustively on period 16 yields 2525 periodic points. It should also be noted that error checking devices were used to ensure that poles were not mistaken for periodic points. These values were also confirmed using Maple.

increases, the number of periodic orbits increases exponentially. Letting the program run exhaustively on period 16 yields 2525 periodic points. It should also be noted that error checking devices were used to ensure that poles were not mistaken for periodic points. These values were also confirmed using Maple.

From this numerical evidence, we observe some noteworthy behavior. For instance, a period-doubling cas- cade to chaos is readily apparent from our data, as shown in Table 2. These values correspond well to the universal rate of doubling given by Feigenbaum’s constant. The period doubling can also be seen in the bi- furcation diagram obtained by following the orbits of both free critical points (see Figure 6).

The value ![]() is a key divider for much of the interesting dynamical behavior. For example, due to the structure of the graph of

is a key divider for much of the interesting dynamical behavior. For example, due to the structure of the graph of![]() , there can be no super-attracting cycles of odd period until

, there can be no super-attracting cycles of odd period until![]() . For

. For

![]()

Table 2. A table illustrating the typical period-doubling route to chaos. Each ![]() -value corresponds to a super-attracting period

-value corresponds to a super-attracting period ![]() cycle for the corresponding Newton map.

cycle for the corresponding Newton map.

![]() , the signs of each element in the orbit of either critical point must alternate, thus making only even periodic cycles possible. This is indicated clearly in Table 1 for

, the signs of each element in the orbit of either critical point must alternate, thus making only even periodic cycles possible. This is indicated clearly in Table 1 for ![]() and

and![]() . Moreover, for

. Moreover, for ![]() -values close to

-values close to![]() , the image of both free critical points is close to the pole at zero and consequently, further iteration leads to convergence to either

, the image of both free critical points is close to the pole at zero and consequently, further iteration leads to convergence to either ![]() or

or![]() . As long as the image of the critical points is trapped close to the pole at zero, the long-term behavior will be convergence to roots. This explains the gap in the center of Figure 6.

. As long as the image of the critical points is trapped close to the pole at zero, the long-term behavior will be convergence to roots. This explains the gap in the center of Figure 6.

It is important to note that in most cases, the free critical points lie on disjoint periodic orbits of the same period. Except for ![]() and

and![]() , all the parameter values in Table 1 are for two disjoint periodic cycles. This is always the case when the period is odd.

, all the parameter values in Table 1 are for two disjoint periodic cycles. This is always the case when the period is odd.

Lemma 4 For ![]() -values corresponding to super-attracting periodic cycles of odd period,

-values corresponding to super-attracting periodic cycles of odd period, ![]() and

and ![]() do not lie on the same orbit.

do not lie on the same orbit.

Proof Without loss of generality, suppose ![]() for some primitive odd period

for some primitive odd period![]() . By contradiction, suppose that

. By contradiction, suppose that ![]() and

and ![]() lie on the same periodic orbit. This implies that

lie on the same periodic orbit. This implies that ![]() for some

for some![]() . However, since

. However, since ![]() is an odd function and

is an odd function and![]() , this also implies that

, this also implies that![]() . Then, by a simple substitution we have

. Then, by a simple substitution we have

![]()

However, we also have that![]() . Therefore, we see that

. Therefore, we see that ![]() is periodic with even period

is periodic with even period![]() . Again, given the symmetry of

. Again, given the symmetry of![]() , this also implies that

, this also implies that ![]() is periodic with even period

is periodic with even period![]() . Since

. Since ![]() and

and ![]() is the least period of the orbit, it follows that

is the least period of the orbit, it follows that![]() . But this contradicts the fact that

. But this contradicts the fact that ![]() is odd.

is odd. ![]()

The birth of two disjoint super-attracting period ![]() -cycles usually arises from a pitch-fork bifurcation. In the rare case when there is a single cycle containing both free critical points on the orbit, a saddle-node bifurcation occurs (see Figure 7). These two types of bifurcations transpire remarkably close together in parameter space, with the saddle-node bifurcation taking place first. For example, when

-cycles usually arises from a pitch-fork bifurcation. In the rare case when there is a single cycle containing both free critical points on the orbit, a saddle-node bifurcation occurs (see Figure 7). These two types of bifurcations transpire remarkably close together in parameter space, with the saddle-node bifurcation taking place first. For example, when![]() , the successive values are

, the successive values are ![]() (same cycle) followed by

(same cycle) followed by ![]() (different cycles). For period

(different cycles). For period![]() , the parameter values are only

, the parameter values are only ![]() apart.

apart.

4. The General Case for ![]()

Unfortunately, once we leave the real and imaginary axes in the ![]() -parameter plane, we are no longer able to work with the simplified versions of our Newton map. Using a computer, we follow the orbits of both free critical points under

-parameter plane, we are no longer able to work with the simplified versions of our Newton map. Using a computer, we follow the orbits of both free critical points under ![]() as

as ![]() varies, producing an intriguing picture of the parameter plane (indicated on the left in Figure 8). The deeper red colors indicate faster convergence to a root, while the lighter colors indicate a slower convergence. Black represents

varies, producing an intriguing picture of the parameter plane (indicated on the left in Figure 8). The deeper red colors indicate faster convergence to a root, while the lighter colors indicate a slower convergence. Black represents ![]() -values where one or both critical points fails to converge to within

-values where one or both critical points fails to converge to within ![]() of a root after 100 iterations. The same color scheme is used for all figures shown in the parameter plane.

of a root after 100 iterations. The same color scheme is used for all figures shown in the parameter plane.

Much of the analytic work we have done up to this point will be useful in explaining the general structure and interesting figures in the parameter plane for![]() . Although quite intricate, there are a few phenomena that can be explained via connections with the work of Milnor on the general case of a complex cubic polynomial [8]. We find a striking similarity between the dynamical behavior of

. Although quite intricate, there are a few phenomena that can be explained via connections with the work of Milnor on the general case of a complex cubic polynomial [8]. We find a striking similarity between the dynamical behavior of ![]() and that of a general complex cubic-

and that of a general complex cubic-

polynomial. This is not entirely surprising, since a generic cubic map has two free critical points, exactly the case for![]() . In [8] , Milnor classifies four types of hyperbolic components in the parameter plane for the generic cubic based on the orbits of the critical points. These four cases are referred to as adjacent critical points, bitransitive, capture and disjoint periodic sinks. Only the second and fourth cases are relevant to our study. We adapt Milnor’s definition to our problem.

. In [8] , Milnor classifies four types of hyperbolic components in the parameter plane for the generic cubic based on the orbits of the critical points. These four cases are referred to as adjacent critical points, bitransitive, capture and disjoint periodic sinks. Only the second and fourth cases are relevant to our study. We adapt Milnor’s definition to our problem.

Definition 2 (Milnor [8] ) Suppose that both free critical points ![]() converge toward attracting periodic orbits

converge toward attracting periodic orbits ![]() distinct from the roots of

distinct from the roots of![]() . Let

. Let ![]() be the open set of all points in the basin of attraction of

be the open set of all points in the basin of attraction of![]() .

.

Bitransitive: The two free critical points belong to different components ![]() and

and ![]() of

of![]() , but there exist natural numbers

, but there exist natural numbers ![]() and

and ![]() such that

such that ![]() and

and![]() . We assume that

. We assume that ![]() and

and ![]() are primitive, so that both

are primitive, so that both ![]() and

and ![]() have period

have period![]() .

.

Disjoint Periodic Sinks: The two free critical points belong to different components ![]() and

and![]() , where no forward image of

, where no forward image of ![]() is equal to

is equal to ![]() and vice versa. In this case, there exist natural numbers

and vice versa. In this case, there exist natural numbers ![]() and

and ![]() with

with ![]() and

and![]() .

.

Milnor characterizes the types of fractal-like figures we should expect to see in the parameter plane for each case, along with a prototype map. Not surprisingly, there are different figures depending on the type and behavior of the critical points. In the bitransitive case, one finds either a swallow configuration (indicated on the right in Figure 8) or a three-pointed configuration Milnor refers to as a tricorn (indicated on the left in Figure 9). For the swallow configuration, the prototypical dynamical system is the family of real maps ![]() with parameters

with parameters ![]() (so the model swallow lives in

(so the model swallow lives in![]() ). For our Newton map

). For our Newton map![]() , the center point of each swallow configuration appears to correspond to the situation where the two real free critical points lie on the same periodic cycle. As discussed in Section 3.2, this occurs for the parameter values

, the center point of each swallow configuration appears to correspond to the situation where the two real free critical points lie on the same periodic cycle. As discussed in Section 3.2, this occurs for the parameter values ![]() and

and![]() . Moreover, since the free critical points are real inside the hyperbolas displayed in Figure 2, we only see swallow configurations in this part of the parameter plane.

. Moreover, since the free critical points are real inside the hyperbolas displayed in Figure 2, we only see swallow configurations in this part of the parameter plane.

For the tricorn, the model is the complex map![]() . The tricorn actually contains three embedded copies of the Mandelbrot set, where the cusp of each has been stretched out over a triangular region, joining them in a peculiar fashion. The difference between the tricorn and swallow configuration is the type of critical points. For the swallow, we have real distinct critical points, while for the tricorn, we have a complex conjugate pair. Due to Lemma 2, inverting the key parameter values

. The tricorn actually contains three embedded copies of the Mandelbrot set, where the cusp of each has been stretched out over a triangular region, joining them in a peculiar fashion. The difference between the tricorn and swallow configuration is the type of critical points. For the swallow, we have real distinct critical points, while for the tricorn, we have a complex conjugate pair. Due to Lemma 2, inverting the key parameter values ![]() and

and ![]() on the imaginary axis gives a conjugate dynamical system. However, the real, symmetric free critical points are mapped to a pure-imaginary conjugate pair under the conjugacy. This explains why we see tricorns in the parameter plane centered at the

on the imaginary axis gives a conjugate dynamical system. However, the real, symmetric free critical points are mapped to a pure-imaginary conjugate pair under the conjugacy. This explains why we see tricorns in the parameter plane centered at the ![]() - values

- values ![]() and

and ![]() and swallow configurations at their inverted counterparts.

and swallow configurations at their inverted counterparts.

In the case of disjoint periodic sinks, there is either a product configuration (two long, thin, black strips stretched across each other) or an actual copy of the Mandelbrot set itself (indicated on the right in Figure 9). The defining map for the product configuration consists of the two disjoint real functions ![]() with

with![]() . As with the swallow configuration, this involves two real critical points as well, although now they are free to find distinct periodic cycles. Enlarging the parameter plane about the value

. As with the swallow configuration, this involves two real critical points as well, although now they are free to find distinct periodic cycles. Enlarging the parameter plane about the value ![]() yields such a configuration because the free critical points of

yields such a configuration because the free critical points of ![]() are real and lie on two distinct super-attracting period 3-cycles. According to Milnor’s work, we see a Mandelbrot-like set at the inversion of this value,

are real and lie on two distinct super-attracting period 3-cycles. According to Milnor’s work, we see a Mandelbrot-like set at the inversion of this value, ![]() , because the free-critical points are mapped to a pure-imaginary conjugate pair under the conjugacy

, because the free-critical points are mapped to a pure-imaginary conjugate pair under the conjugacy ![]() and this pair lie on distinct attracting cycles. In this case, the prototype map is simply

and this pair lie on distinct attracting cycles. In this case, the prototype map is simply ![]() with

with![]() , the usual defining map for the Mandelbrot set. The disjoint periodic sink cases yield ``simpler’’ dynamical phenomenon because the orbits of the critical points stay away from each other, leading to the decoupled prototype maps.

, the usual defining map for the Mandelbrot set. The disjoint periodic sink cases yield ``simpler’’ dynamical phenomenon because the orbits of the critical points stay away from each other, leading to the decoupled prototype maps.

Throughout our discussion, we see that the different possible orbits of the free critical points determine the types of fractal-like figures found in the parameter plane. Our detailed analysis of the special case restricting ![]() to the imaginary axis has provided a useful guide explaining the locations of these figures. However, there are some exceptions worth mentioning. For example, there are disjoint periodic sink values very close to bitransitive values that are contained inside a swallow configuration. Given our limited resolution and computational resources, we are unable to numerically substantiate the claim that every parameter value corresponding to a disjoint periodic sink lies at the center of a product configuration or a Mandelbrot-like set. This discrepancy is most likely attributable to the fact that

to the imaginary axis has provided a useful guide explaining the locations of these figures. However, there are some exceptions worth mentioning. For example, there are disjoint periodic sink values very close to bitransitive values that are contained inside a swallow configuration. Given our limited resolution and computational resources, we are unable to numerically substantiate the claim that every parameter value corresponding to a disjoint periodic sink lies at the center of a product configuration or a Mandelbrot-like set. This discrepancy is most likely attributable to the fact that ![]() is a cubic-like map, as introduced by Douady and Hubbard [7], and not an actual cubic polynomial. Nevertheless, after plotting the long-term behavior of each critical point separately and investigating the location of several swallow configurations, we have obtained strong numerical evidence in support of the following conjecture:

is a cubic-like map, as introduced by Douady and Hubbard [7], and not an actual cubic polynomial. Nevertheless, after plotting the long-term behavior of each critical point separately and investigating the location of several swallow configurations, we have obtained strong numerical evidence in support of the following conjecture:

Conjecture 1 Each bitransitive ![]() -value corresponding to the two free critical points sharing the same super-attracting

-value corresponding to the two free critical points sharing the same super-attracting ![]() -cycle lies at the center of a swallow configuration in the parameter plane.

-cycle lies at the center of a swallow configuration in the parameter plane.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, we point out one more feature of the parameter plane that can be analytically derived. The yellow diamond shaped boundary that encompasses the interesting dynamical behavior in the parameter plane (in- dicated on the left in Figure 8) is defined by those ![]() -values where both

-values where both ![]() and

and ![]() simultaneously vanish. Letting

simultaneously vanish. Letting![]() , this occurs on the algebraic curve

, this occurs on the algebraic curve ![]() defined by the equation

defined by the equation

![]()

For any parameter value on![]() , one or both of the free critical points coincide with poles of

, one or both of the free critical points coincide with poles of ![]() and thus map to the fixed point at

and thus map to the fixed point at![]() . Taking successive pre-images of these curves appears to define the sequence of intertwining yellow “leaves” that approach the real axis.

. Taking successive pre-images of these curves appears to define the sequence of intertwining yellow “leaves” that approach the real axis.

We have analytically and numerically investigated Newton’s method ![]() applied to a highly symmetric family of fourth degree complex polynomials. Using techniques from both real and complex dynamical systems theory, we were able to study some reductions of our Newton map that shed significant light on the varied dynamical behavior of this system. Remarkably, we find quite intricate and complicated fractal-like figures throughout the parameter plane for this simple system. Milnor’s work on the complex cubic polynomial com- bined with our understanding of the dynamics for

applied to a highly symmetric family of fourth degree complex polynomials. Using techniques from both real and complex dynamical systems theory, we were able to study some reductions of our Newton map that shed significant light on the varied dynamical behavior of this system. Remarkably, we find quite intricate and complicated fractal-like figures throughout the parameter plane for this simple system. Milnor’s work on the complex cubic polynomial com- bined with our understanding of the dynamics for ![]() with

with ![]() purely imaginary provided some rationale for the location and types of fractals encountered.

purely imaginary provided some rationale for the location and types of fractals encountered.

Acknowledgements

TOB would like to thank the Department of Mathematics and Computer Science at the College of the Holy Cross for providing an enjoyable and supportive atmosphere throughout his undergraduate career. Funding for TOB was provided by a Council on Undergraduate Research Student Summer Research Fellowship in Mathe- matics and Science. GR would like to thank Paul Blanchard for pointing him in the direction of this problem and for several interesting discussions concerning this work. He would also like to thank Bruce Peckham for ongoing and insightful discussions on Newton’s method.