Received 3 December 2015; accepted 17 December 2015; published 22 December 2015

Subject Areas: Mechanics, Modern Physics, Special Theory of Relativity

1. Introduction

In the scientific literature many papers can be found that deal with alternative theories to the Einstein general theory of relativity (GTR) to model the remarkable observation of Le Verrier with regards to the perihelion precession of Mercury (PPM) which cannot be explained with the influence of other planets. These theories are metric GTR, non-metric GTR, combination of the special theory of relativity (STR) with the Lagrangian (classical or relativistic), etc.

In this work a correction to the balance equation between the force given by Newton 2nd law of motion and Newton gravitational force is introduced to calculate the inherent PPM. The objective of this manuscript is to show that the intrinsic advance of the longitude of the perihelion of Mercury (ALPM) can be accounted for using that correction.

1) Modification of the balance between the Newton 2nd law of motion and the Newton gravitational force

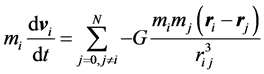

Equating Newton’s 2nd law to the Newton gravitational force, a non-linear ODE is obtained for N point-mass planets in the solar system [1] , which in vector notation is:

(1)

(1)

The solution of Equation (1) for N = 1 does not yield an ALPM. Einstein general theory of relativity (GTR) addressed this problem by introducing a curved space-time concept. In this work an empirical approach is used to address the problem.

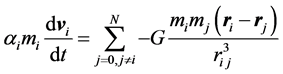

Let’s modify the l. h. s. of Equation (1) (the l. h. s. is used just for convenience) as

(2)

(2)

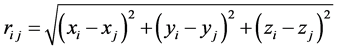

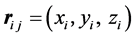

where

(3)

(3)

: The speed of the gravitational interaction,

: The speed of the gravitational interaction, .

.

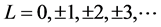

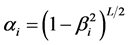

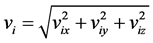

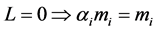

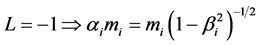

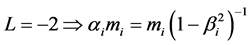

The coefficient of the acceleration for some values of L (assuming : the speed of light in vacuum) is identified as:

: the speed of light in vacuum) is identified as:

, Mass in Newton theory;

, Mass in Newton theory;

, Mass in Lorentz theory cited in Granek [2] and in kinetic energy Equation of a slow electron, Einstein [3] ;

, Mass in Lorentz theory cited in Granek [2] and in kinetic energy Equation of a slow electron, Einstein [3] ;

, Transverse mass, Einstein [3] ;

, Transverse mass, Einstein [3] ;

![]() , Longitudinal mass in Lorentz theory cited in Granek [2] and in Einstein [3] .

, Longitudinal mass in Lorentz theory cited in Granek [2] and in Einstein [3] .

Other equations could be obtained from the Planck balance equation, adapted to a gravitational force:

![]() (4)

(4)

2) Numerical Solution of the System of Differential Equations

Equation (1) for the heliocentric coordinate system is written as [4] :

![]()

![]()

k = 0.01720209895 is the Gaussian constant (the Newton gravitational constant expressed in terms of the astronomical unit length, day and taking the Sun mass as 1). Similarly Equation (2) is written as

![]() (5)

(5)

Assuming![]() .

.

The finite difference method (using a standard two point- finite difference applied to the concept of acceleration and speed to obtain the next value of the speed and the position respectively), with a very small integration step![]() , was used to solve Equation (5). Even though it is not an efficient method it is used to have a direct estimate of the perihelion which is used as a check to the perihelion calculation from the orbital elements.

, was used to solve Equation (5). Even though it is not an efficient method it is used to have a direct estimate of the perihelion which is used as a check to the perihelion calculation from the orbital elements.

The longitude of the perihelion, ![]() , for Mercury is calculated from the 3D position and velocity vectors obtained from the numerical solution of Equation (5). It is calculated as

, for Mercury is calculated from the 3D position and velocity vectors obtained from the numerical solution of Equation (5). It is calculated as![]() , where

, where ![]() is the

is the

longitude of the ascending node and ![]() is the argument of the perihelion. The rate of

is the argument of the perihelion. The rate of ![]() is determined as the slope,

is determined as the slope, ![]() , of a linear trend of

, of a linear trend of ![]() with t.

with t.

2. Computational Results and Analysis

The reciprocal mass and initial conditions ![]() were taken from Table 1 and Table 3 of Le Guyader paper [5] . The positions and velocities are for the Julian date JJ = 2,451,600.5 referred to the dynamical ecliptic and equinox J2000.

were taken from Table 1 and Table 3 of Le Guyader paper [5] . The positions and velocities are for the Julian date JJ = 2,451,600.5 referred to the dynamical ecliptic and equinox J2000.

Table 1 shows the results of S calculation for Mercury in arc-sec/cy based on the slopes of the linear fits shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2 (N = 1, the total integration time is 4 × 104 days (~109.5 years), using a positive ![]() days, the time between two consecutive points is 88 days). From that table it can be seen that for negative L the slope is negative which is in contradiction with the experimental results for Mercury. For a positive L however the slope is positive, specifically for L = 6, S = 42.95 which is in very close agreement with Le Verrier observation. Note however that a positive L implies a different trend of the mass variation with the speed when compared to the ones of the special theory of relativity and electron theory.

days, the time between two consecutive points is 88 days). From that table it can be seen that for negative L the slope is negative which is in contradiction with the experimental results for Mercury. For a positive L however the slope is positive, specifically for L = 6, S = 42.95 which is in very close agreement with Le Verrier observation. Note however that a positive L implies a different trend of the mass variation with the speed when compared to the ones of the special theory of relativity and electron theory.

![]()

Figure 1. Calculation of ![]() in degree/day for the Sun-Mercury system (negative L).

in degree/day for the Sun-Mercury system (negative L).

![]()

Figure 2. Calculation of ![]() in degree/day for the Sun-Mercury system (positive L).

in degree/day for the Sun-Mercury system (positive L).

![]()

Table 1. Calculation of ![]() in arc-sec/cy for the Sun-Mercury system.

in arc-sec/cy for the Sun-Mercury system.

Note that in this case (the two-body problem) S is not periodic and it is linearly correlated with time and L and that the discrete change is due to the discrete value of L used. Note also that the difference between any two consecutive values of L is about 7, that a linear fit of S with positive L results in a slope of 7.1618, and that the ratio of SL/S1 is ~L. The Einstein GTR equation of motion (for m = m0) was also solved numerically, an S = 42.97”/cy was obtained.

It could be worthy to check if L is a constant for the solar planetary system and other bound-orbital-gravita- tional systems or if it represents a state of the moving body. It could also be worthy to assess the potential impact on other gravitational problems as for example on the dark energy/matter problem. It is hoped that a derivation for L = 6 is found.

Table 2 shows the results of S calculation for Mercury based on the slopes of the linear fits shown in Figure 3 for the 10-body problem (N = 9, L = 0, −6, 6). From that table it can be seen that the result for L = 0 (Newtonian theory) is very close to 528.95 “/cy calculated in Narlikar and Rana [6] and that for L = −6 the result is very far (for L = −1 the result will be closer but still less than the rate predicted by the Newtonian theory) from the experimental value of 574.24 reported in the same paper in reference to Bretagnon (1982). The value for L = 6 however is significantly closer to the experimental value than the result for L = −6 and the difference (2.56”/cy) with respect to the experimental value could become only ~0.26”/cy when considering the effect of the slow motion of the ecliptic (~2.30’’/cy) reported also in [6] in the note added in proof.

Note that in this case (the 10-body problem) S is periodically and linearly correlated with time, large fluctuations and periodicities are due to, according to [6] , the relative proximity of Mercury and Venus and the repeated configuration of Mercury, Venus, Earth and Jupiter over time, respectively.

Note also that the S (intrinsic to Mercury) difference (for L = 6) between the results of Table 1 and Table 2 is very small (0.03”/cy). The calculation for L = 6 was repeated with ![]() days for which S = 571.71 was obtained. Additionally the total integration time was doubled (~219 years,

days for which S = 571.71 was obtained. Additionally the total integration time was doubled (~219 years, ![]() days) for which S = 571.69 was obtained which is a very small impact.

days) for which S = 571.69 was obtained which is a very small impact.

3. Concluding Remarks

The longitude of the perihelion advance intrinsic to Mercury was accounted for in the two and 10-body problem by using a correction to the balance between the Newton 2nd law of motion and the Newton gravitational force.

![]()

Figure 3. Calculation of ![]() in degree/day for the 10-body problem.

in degree/day for the 10-body problem.

![]()

Table 2. Calculation of ![]() in arc-sec/cy for Mercury (10-body problem).

in arc-sec/cy for Mercury (10-body problem).

The correction, that suggests a variation of the mass with the moving body speed, is different from what is usually expected from the special theory of relativity and from the electron theory (L is positive instead of negative).

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Dr. M. Krizek for his valuable comments and suggestions.