Radiation Forces on a Dielectric Sphere Produced by Finite Olver-Gaussian Beams ()

Received 11 October 2015; accepted 21 December 2015; published 25 December 2015

1. Introduction

In recent years, the accelerating finite Airy beam has been introduced within the framework of laser optics field by Siviloglou et al. [1] [2] , on the basis of the result published by Berry and Balzas [3] , in the context of the quantum mechanics, whose have introduced the Airy wave packet function as a solution of the Schrödinger equation in 1979. This new laser beams family exhibits many important characteristics, which permit them good candidates in several applications such as manipulating, trapping and transport of particles. It has an intensity profile that tends to be accelerated transversely during propagation. This leads to its experimental realization where most of the interesting properties were observed directly in many configurations [2] , and the study of its ballistic dynamics shows that these waves follow parabolic trajectories similar to these of projectiles moving under the action of uniform gravitational field [4] [5] . This can absolutely help in handling micron particles. This topic was discussed in the literature first by Ashkin [6] and demonstrated how to manipulate three-dime- nsional trapping of a dielectric particle by using a highly focused laser beam thanks to their wide applications in manipulating various particles such as neutral atoms [7] , molecules [8] , micron-sized dielectric particles [9] , DNA molecules [10] and living biological cells [11] -[13] . The optical traps or tweezers have also attracted attention in many literature works [14] - [18] . The radiation forces explained by scattering and gradient forces are generated by the exchange of momentum and energy between photons and particles.

As known, the first conventional optical trap is constructed by the fundamental Gaussian beams because it has a Gaussian peak in the cross profile and it is suitable for trapping the particle with the index of refraction higher than that of ambient [7] . However, many researchers have demonstrated that other beams are also useful in trapping particles such as doughnut laser beams including Bessel beams which are more available in the trapping and manipulation of process [19] - [21] . The trapping characteristics of different beams, such as Laguerre-Gaus- sian [22] , hollow-Gaussian [23] , Bessel-Gaussian [24] , cylindrical vector [25] , Gaussian Schell model [26] and flat-topped-Gaussian beams [27] , have been studied.

The “non-diffracting” Airy beam has also attracted attention for its use in trapping particles because of its potential applications in several domains of the same context, such as: guidance plasma [28] , acceleration of electrons in vacuum [29] , production of three optical bullets dimensions [30] and optical micromanipulation [31] [32] . Opposed to other laser beams, the Airy family beam can transport microparticles along curved self- healed paths, and remove particles or cells from a section of a sample chamber [33] . Its novelty is that the trapping potential landscape tends to freely self-bend during propagation, and also its bend degree can be controlled, and the direction of acceleration can be switched by a nonlinear optical method [33] , and the micromanipulation by Airy beam reported to date is related to Mie particles [31] [32] whose radii are larger than the wavelength. All these tunable properties make the Airy beam as a versatile and powerful tool for many optical manipulations. Our work done in this review is based on the above cited theoretical studies dealing the radiation force on spherical particles [8] - [10] [33] - [37] . Of these, we cite the theoretical analysis of the radiation pressure force of laser light on a dielectric sphere in the Rayleigh regime developed by Harada and Asakura [33] , the method proposed by Rohrbach and Stelzer [34] , to calculate the forces trapping dielectric particles and the investigation made by Zemánek et al. [35] about the rule of Gaussian beams in optical trapping of Rayleigh particles. Yet, Cheng et al. [36] have developed an analysis of optical trapping and propulsion of Rayleigh particles using the ordinary Airy beam. And in Ref. [37] , Svoboda and Block have discussed some biological applications of optical forces.

In this paper, we consider a theoretical description of the radiation forces produced by the Finite Olver- Gaussian beam in Rayleigh scattering regime when the radius of particles is much smaller than the wavelength. Note that the new beams family, called “Finite Olver-Gaussian beams”, is introduced within the optic field and their characteristics and propagation properties in aligned and misaligned optical systems are studied and examined for the first time by our research group [37] - [39] .

2. Fields of Finite Olver-Gaussian Beams through an ABCD Optical System

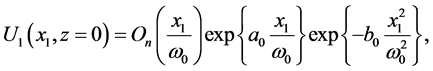

The electrical field of FOG Bs at the input plane (z = 0) is defined by Belafhal et al. [38] as

(1)

(1)

where  is the order of FOGBs. For

is the order of FOGBs. For , we will treat the ordinary finite Airy beam with

, we will treat the ordinary finite Airy beam with  is the truncation coefficient and

is the truncation coefficient and  is a coefficient to be equal to 1 or 0, depend that the incident beam is modulated by a Gaussian envelope or not, respectively. Due to the special properties of Airy Beam, it can absolutely be used to guide and trap neutral particles.

is a coefficient to be equal to 1 or 0, depend that the incident beam is modulated by a Gaussian envelope or not, respectively. Due to the special properties of Airy Beam, it can absolutely be used to guide and trap neutral particles.

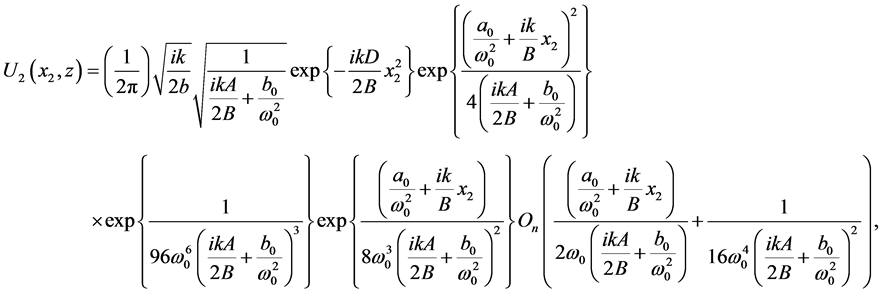

Under the paraxial approximation, the electrical field of FOGBs beam passing via any ABCD optical system can be expressed as [39] .

(2)

(2)

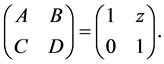

where  is the wave number and

is the wave number and  being the wavelength. A, B, C and D are the transfer matrix elements of the paraxial optical system. z is the distance between the input and the output planes. Consider now the FOGBs propagates through a free space described by the following transfer matrix

being the wavelength. A, B, C and D are the transfer matrix elements of the paraxial optical system. z is the distance between the input and the output planes. Consider now the FOGBs propagates through a free space described by the following transfer matrix

(3)

(3)

Substituting Equation (3) in Equation (2), one obtains the intensity distribution of the FOGBs through a free space.

3. Theory of the Radiation on a Dielectric Sphere

Assume that the particle is sufficiently small compared to the wavelength of the laser beam i.e. , where a is the radius of the particle and

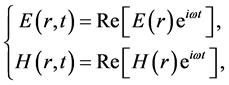

, where a is the radius of the particle and  is the wavelength of the incident beam. So, in the Rayleigh scattering the particle could be treated as a point dipole. Two types of radiation forces can be examined: the scattering force and the gradient one. The electric field is polarized in the x -direction. The center of the particle is located at the position (x, z). The physical quantities of the field vectors of the electromagnetic wave are real functions of time and space given by [33]

is the wavelength of the incident beam. So, in the Rayleigh scattering the particle could be treated as a point dipole. Two types of radiation forces can be examined: the scattering force and the gradient one. The electric field is polarized in the x -direction. The center of the particle is located at the position (x, z). The physical quantities of the field vectors of the electromagnetic wave are real functions of time and space given by [33]

(4)

(4)

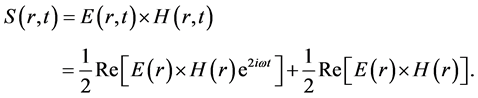

with  is the temporal angular frequency of the laser beam. The instantaneous energy flux crossing an area per time unit in the beam propagation direction corresponding to the propagation vector is given by [33]

is the temporal angular frequency of the laser beam. The instantaneous energy flux crossing an area per time unit in the beam propagation direction corresponding to the propagation vector is given by [33]

(5)

(5)

The measurable physical quantity which evaluates the radiation force, of the light, is the beam intensity at the position  which is defined as

which is defined as

![]() (6)

(6)

In the last equation, ![]() is the refractive index of a surrounding medium,

is the refractive index of a surrounding medium, ![]() is the speed of the light in the vacuum.

is the speed of the light in the vacuum. ![]() and

and ![]() are the dielectric constant and the magnetic permeability in the vacuum, respectively, and

are the dielectric constant and the magnetic permeability in the vacuum, respectively, and ![]() is a unity vector along the wave vector.

is a unity vector along the wave vector.

The radiation pressure force exerted on the particle in the Rayleigh regime is described by two components actions on the dipole. One of these forces is the scattering force. As known, the electric field oscillates harmonically in time, and the induced point dipole follows with synchronization the electric field which gives that the particle acts as an oscillating electric dipole which radiates secondary or scattered waves in all directions. The scattering force is given and discussed in [37]

![]() (7)

(7)

where ![]() is the cross section force of the radiation pressure of the particle in the Rayleigh approximation and is given by [37]

is the cross section force of the radiation pressure of the particle in the Rayleigh approximation and is given by [37]

![]() (8)

(8)

with ![]() is the relative refractive index of the particle,

is the relative refractive index of the particle, ![]() is the refractive index of the ambient,

is the refractive index of the ambient, ![]() is the refractive index of the particle and

is the refractive index of the particle and ![]() is the radius of the particle.

is the radius of the particle.

The other component is a gradient force due to the Lorentz force acting on the dipole induced by the electromagnetic field [37] . The instantaneous gradient force is defined by [37]

![]() (9)

(9)

where ![]() As a result of the Maxwell equations, one have

As a result of the Maxwell equations, one have![]() , which gives the following expression

, which gives the following expression

![]() (10)

(10)

with ![]()

4. Numerical Simulations and Results Discussions

By the use of the theory of the radiation on a dielectric sphere, exposed in the previous section, we will prove numerically that the considered beams family drags particles into their intensity peaks. The parameters chosen in the calculations are: the radius of the particle is![]() , the refractive index are

, the refractive index are![]() ,

, ![]() and the wavelength is

and the wavelength is ![]() and the spot size in the medium is

and the spot size in the medium is![]() . The coefficients

. The coefficients ![]() and

and ![]() take the value 0.1. In our numerical calculations, we simulate the radiation force produced by the incident focused FOGBs considered in one-dimension. We choose the peak intensity of the input beam as

take the value 0.1. In our numerical calculations, we simulate the radiation force produced by the incident focused FOGBs considered in one-dimension. We choose the peak intensity of the input beam as ![]() with the above numerical parameters of

with the above numerical parameters of ![]() and

and![]() . As well known, for a stable optical trapping, when a particle moves away, the radiation forces will pull the particle it back to the equilibrium position. Apparently, there exist two types of radiation forces: the gradient and the scattering forces. The both could be used to pulls, manipulates and traps the particles. In our case, we assume that the radius of the particle is much smaller than the wavelength of the laser beam, so the Rayleigh approximation theory is applied. Under this approximation, the radiation forces include the scattering and the gradient ones which are regarded as the key for trapping the particle are responsible to pull particles towards the center and the scattering force tends to push the small Rayleigh particle out along the direction of the beam propagation and destabilize the optical trap. So, it leads to particle departure from the equilibrium position. While for the large Rayleigh distance, there is a competition between the axial gradient force and the scattering force. This may determine whether the particle can be trapped or not in the axial direction.

. As well known, for a stable optical trapping, when a particle moves away, the radiation forces will pull the particle it back to the equilibrium position. Apparently, there exist two types of radiation forces: the gradient and the scattering forces. The both could be used to pulls, manipulates and traps the particles. In our case, we assume that the radius of the particle is much smaller than the wavelength of the laser beam, so the Rayleigh approximation theory is applied. Under this approximation, the radiation forces include the scattering and the gradient ones which are regarded as the key for trapping the particle are responsible to pull particles towards the center and the scattering force tends to push the small Rayleigh particle out along the direction of the beam propagation and destabilize the optical trap. So, it leads to particle departure from the equilibrium position. While for the large Rayleigh distance, there is a competition between the axial gradient force and the scattering force. This may determine whether the particle can be trapped or not in the axial direction.

Figures 1-4 show the transverse gradient force along x-axis for the various orders n = 0, 1 and 2 at different axial positions z and with different values of the beam size![]() . The gradient force alternates between the positive and negative directions. The positive gradient force means the direction of transverse gradient force is in +x-direction and the negative gradient force means in the negative x -direction. So it depends upon the particle’s position relative to nearby position of the optical intensity peak. These suggest that the Rayleigh particle in the Finite Olver-Gaussian beam will be pulled into nearby intensity peak and transported along the propagation direction.

. The gradient force alternates between the positive and negative directions. The positive gradient force means the direction of transverse gradient force is in +x-direction and the negative gradient force means in the negative x -direction. So it depends upon the particle’s position relative to nearby position of the optical intensity peak. These suggest that the Rayleigh particle in the Finite Olver-Gaussian beam will be pulled into nearby intensity peak and transported along the propagation direction.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Figure 1. Transverse gradient force of finite zeroth-order Olver-Gaussian beam versus x for different values of ω0 and for z = 500 μm.

![]()

![]() (a) (b)

(a) (b)

Figure 3. Transverse gradient force of Finite Olver-Gaussian beam of second order (n = 2) versus x for different: (a) Propag- ation distances z, (b) Beam width size.

![]()

![]() (a) (b)

(a) (b)

Figure 4. Scattering force of Finite Olver-Gaussian beam of first order (n = 1) versus x for different: (a) Propaga- tion distance z (ω0 = 5 μm), (b) Beam witdth size ω0 (z = 500 μm).

![]()

![]() (a) (b)

(a) (b)

Figure 5. Transverse gradient force of Finite Olver-Gaussian beam of first order (n = 1) versus x for different: (a) Propagation distances z (ω0 = 5 μm), (b) Beam witdth size ω0 (z = 500 μm).

![]()

![]() (a) (b)

(a) (b)

Figure 6. Scattering force of finite zeroth-order Olver-Gaussian beam versus x for different: (a) Propagation distances z (ω0 = 5 μm), (b) Beam witdth size ω0 (z = 500 μm).

![]()

![]() (a) (b)

(a) (b)

Figure 7. Scattering force of Finite Olver-Gaussian beam of second order (n = 2) versus x for different: (a) propaga- tion distances z (ω0 = 5 μm), (b) Beam witdth size ω0 (z = 500 μm).

![]()

![]() (a) (b)

(a) (b)![]() (c)

(c)

Figure 8. Example of a scattering force of Finite Olver-Gaussian beam at varying z planes for different beam width size ω0 (z = 500 μm). for: (a): zeroth order (n = 0), (b): first order (n = 1) and (c): second order (n = 2).

Illustrations of Figures 1-4 show that as far as the propagation distance z increases as much as the number of oscillations of the gradient force increases and the zeros of the central lobe and sidelobes move towards the positive x. However, the maxima of the lobes decrease insignificantly with the increase of z. Yet, the gradient force reaches less of zeros and the lobes maximums decrease with the increase of the waist size of the incident Gaussian envelope. The decrease of the maximums lobes with the waist is very significant. In Figures 5-7, we plot the scattering force of the various orders n of the Finite Olver-Gaussian beam versus x for different propagation distances z and different beam width sizes ω0.

As the same as in Figures 1-4 concern the gradient force, from the plots of Figure 5 and Figure 7 about the scattering force, it is pointed that the same remarks are repeated in this case. Figure 8, shows the scattering force of the Finite Olver-Gaussian beam for different orders n along z-axis and with different values of beam size![]() . Our results obtained for the ordinary Airy Beams are compared with those presented in Ref. [36] . Our analysis shows that the radiation forces of focused finite Olver-Gaussian beams may be used to trap and manipulate the Rayleigh dielectric particles and in order to stability trap particles. The axial gradient force must be greatly larger than the scattering force

. Our results obtained for the ordinary Airy Beams are compared with those presented in Ref. [36] . Our analysis shows that the radiation forces of focused finite Olver-Gaussian beams may be used to trap and manipulate the Rayleigh dielectric particles and in order to stability trap particles. The axial gradient force must be greatly larger than the scattering force![]() . This report is called the stability criterion.

. This report is called the stability criterion.

5. Conclusion

We have investigated the radiation force exerted on a dielectric particle in the Rayleigh scattering regime illuminated by FOGBs with different beams order n. Several numerical simulations are carried out in the work, in order to study and analyze the effects of some parameters on the radiation gradient and transverse forces, for instance, the parameters of the laser beam illuminate the dielectric sphere and the propagation distance. The numerical results show that the Finite Olver-Gaussian beams could drag particles by the peaks of intensity and could transport and manipulate them in the inter-lobes. Finally, we conclude that Finite Olver-Gaussian beams may be used in many practical applications of nanotechnology and biotechnology.

NOTES

![]()

*Corresponding author.