1. Introduction

Some quantum phenomena can cause astonishment. The violation of Bell’s inequality is a part of the surprises raised by Quantum Mechanics [1] [2] . This violation means that it would be necessary to give up at least one of the following three assumptions: the principle of locality (two photons can not influence each other at a distance greater than the speed of light), the assumption of causality (to each effect at least one cause) and the assumption of realism (any particle has its own property). After recalling what Bell’s inequality and experimental measures are, we will discuss how this inequality can be violated or not.

This paper is a criticism of Pr Alain Aspect’s demonstration; it is neither a criticism of Bell’s inequality theory, nor of its consequences here before.

2. Experimental Measures of Bell’s Inequality

2.1. The Experimental Set-Up

Hereinafter proposed by Professor John Stewart BELL [3] the experimental set-up:

The source is a stream of 2 entangled photons:

-the two photons leave in two opposite directions.

-“entangled” means that one photon is polarized along θ and the other photon along , it means the entangled photons have the same polarity

, it means the entangled photons have the same polarity .

.

and

and  are separators with switching function depending on the photon polarity (that is to say in the direction of the electric field associated with the photon).

are separators with switching function depending on the photon polarity (that is to say in the direction of the electric field associated with the photon).

,

,

and

and  are four independent photon detectors, or counters.

are four independent photon detectors, or counters.

Experiments done in Paris, Innsbruck and Genève [4] with two-channel polarizers look like Figure 1.

2.2. Measures of Entangled Photons

-if the polarity of the photon is rather parallel to , the photon is leaving to

, the photon is leaving to  detector-otherwise, if the polarity of the photon is rather perpendicular to

detector-otherwise, if the polarity of the photon is rather perpendicular to , the photon is leaving to

, the photon is leaving to  detector

detector

-if the polarity of the other photon is rather parallel to , the photon is leaving to

, the photon is leaving to

-otherwise, if the polarity of the other photon is rather perpendicular to , the photon is leaving to

, the photon is leaving to

When a photon is detected the measurement is conventionally +1, and when it is not detected the measurement is conventionally −1.

Given:

measurement (at the ith throw)

measurement (at the ith throw)

measurement (at the ith throw);

measurement (at the ith throw);  could also be written

could also be written

measurement (at the ith throw)

measurement (at the ith throw)

measurement (at the ith throw);

measurement (at the ith throw);  could also be written

could also be written

is the complement of

is the complement of  [5] : when the photon is detected by

[5] : when the photon is detected by , it is not detected by

, it is not detected by  (and conversely)

(and conversely)

is the complement of

is the complement of : when the photon is detected by

: when the photon is detected by , it is not detected by

, it is not detected by  (and conversely)

(and conversely)

At each entangled photon, by construction:

(1)

(1)

which means  or

or , either the photon is detected by

, either the photon is detected by , or by

, or by  and

and

(2)

(2)

which means  or

or , either the other photon is detected by

, either the other photon is detected by , or by

, or by .

.

2.3. Experimental Measures

The measures are of the form:

1) If the two polarizers are oriented in the same direction, the two photons always behave the same way (transmitted or absorbed depending on the angle of the polarizer with the polarization).

2) If the two polarisers are inclined at an angle of 30˚ with respect to each other, then the two photons have exactly the same behavior in 3/4 cases and in opposite fourth cases.

3) If the two polarisers are inclined at an angle of 60˚ with respect to each other, then the two photons have the same behavior in exactly 1/4 cases and in opposed 3/4 cases [6] .

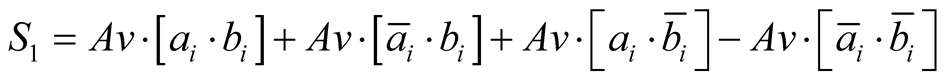

2.4. The Quantum Sum

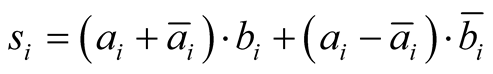

Let us define the first quantum sum : “each pair of particles carries with it sufficient information to calculate the following number” [7]

: “each pair of particles carries with it sufficient information to calculate the following number” [7]

(3)

(3)

Previous quantum sum can also be written as:

(4)

(4)

Remark: another way to write the quantum sum is:

(5)

(5)

where  has thus been noted

has thus been noted  (and consequently

(and consequently  has been noted

has been noted )

)

It is only a convention to call a detector  or

or , and so the measures

, and so the measures  or

or . In practice, it will change the sign of the result

. In practice, it will change the sign of the result , not its absolute value:

, not its absolute value:

(6)

(6)

2.5. Bell’s Inequality Definition

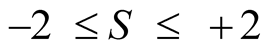

Let us remind what Bell’s inequality definition is:

“Bell’s theorem [or Bell’s inequality] is not defined according to a clear statement that would be found in a reference article” [8] ; so we will hereafter take the definitions given by Professor SCARANI:

“This is the statement of the Bell theorem: if our hypothesis is correct, the average value of must be between −2 and +2. That’s all...” [7] .

must be between −2 and +2. That’s all...” [7] .

Then Bell’s therorem (or inequality) is mathematically transcribed to:

(7)

(7)

with  the average value of

the average value of

2.6. Average Quantum Sum

The sum used in the updated Bell’s inequality definition is: “making measurements on a large number of pairs, it can measure the average value of ” [7] .

” [7] .

Let us call “the average value of ”:

”:

(8)

(8)

the average value of

the average value of  is “the algebraic sum of the four average values corresponding to the measures” [7] , which is mathematically transcripted (see Appendix) by:

is “the algebraic sum of the four average values corresponding to the measures” [7] , which is mathematically transcripted (see Appendix) by:

(9)

(9)

3. Treatment of the Measures

3.1. Treatment from a Wave Function Property

Pr. Valerio Scarani [9] [10] , popularizing Pr Aspect’s demonstration, proceeds starting from the wave function and according to quantum calculation ending up to a property [7] :

(10)

(10)

with

(11)

(11)

Important remark:

This sum  looks like the average sum

looks like the average sum  but it is not the same:

but it is not the same:

²  is function of experimental measures

is function of experimental measures  [cf. Equation (9)];

[cf. Equation (9)];  are a couple of numbers:

are a couple of numbers:

(12)

(12)

²  is function of experimental conditions

is function of experimental conditions  [cf. Equation (10)];

[cf. Equation (10)];  are a couple of angles:

are a couple of angles:

(13)

(13)

Starting again with Equation (10) and Equation (11),

(14)

(14)

(15)

(15)

(16)

(16)

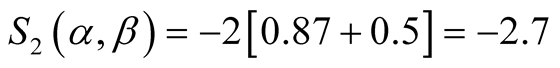

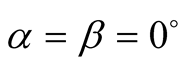

For example, for  and

and :

:

(17)

(17)

(18)

(18)

It would be in this case , according to Equation (10) and Equation (11), violation of Bell’s inequality.

, according to Equation (10) and Equation (11), violation of Bell’s inequality.

Remark: the concern is that this result is the consequence of theoretical calculations dealing with angles  and

and  of the test conditions; it is not the result of measures

of the test conditions; it is not the result of measures  and

and  experimentally found (cf Table A2 in Appendix).

experimentally found (cf Table A2 in Appendix).

3.2. Quantum Sum from the Experimental Measures in a Particular Case

In the previous case where , returning to the experimental measures [cf Table A2 in Appendix], we get Table1

, returning to the experimental measures [cf Table A2 in Appendix], we get Table1

According to the sum definition [cf. Equation (8)],

(19)

(19)

or according to the sum property [cf. Equation (9)],

(20)

(20)

id est:

(21)

(21)

For , the average sum

, the average sum  does not violate Bell’s inequality [as defined in Equation (7)].

does not violate Bell’s inequality [as defined in Equation (7)].

Table 1. Experimental measures with an angle of  processed.

processed.

3.3. Quantum Sum from the Experimental Measures in the General Case

Let us process the three tables (Tables A1-A3) from Appendix into Table2

We can verify that for all experimental measures cf. Equation (9):

(22)

(22)

If we processed from the definition for all experimental measures cf. Equation (8):

(23)

(23)

so processing all experimental measures

(24)

(24)

With all the measures, the average sum  does not violate Bell’s inequality [as defined in Equation (7)].

does not violate Bell’s inequality [as defined in Equation (7)].

So, in the particular case or in general, using the definition , Bell’s inequality is never violated.

, Bell’s inequality is never violated.

3.4. Synthesis about the Two Arguments

Paragraphs 3.1 and 3.2 can be boiled out to the flowchart of Figure 2.

And from a more general point of view, the synthesis flowchart will be Figure 3.

Table 2. Experimental measures processed.

3.5. Application to the Aspect’s Experiment of 1983

In present paper, analysis has been done mainly from Dr. Scarani presentation, according to the property

[cf Equation10] with  [cf. Equation (11)]

[cf. Equation (11)]

Then the extremum are for values as  or

or  [cf. Equation (18)], and

[cf. Equation (18)], and  or

or .

.

It is interesting to note than in Aspect's experiment of 1983 [3] , the extremum were for values as  (or

(or ) and

) and  (or

(or ). The reason comes the experiment was different (in BCHSH experiment the difference between two angles are not

). The reason comes the experiment was different (in BCHSH experiment the difference between two angles are not  but are

but are ), and so property was different:

), and so property was different:

(25)

(25)

with

(26)

(26)

Let us correlate 1983 notation with present notation (see Table 3):

(27)

(27)

which is equivalent to

(28)

(28)

Equation (28) is exactly the same than the Equation (4) for the definition of Bell’s inequality.

So we can use the same flowchart (Figure 4) to explain the difference of results between the definition of Bell’s inequality and the property of a wave function: Starting from the experiment and the definition of , Bell’s inequality is not violated.

, Bell’s inequality is not violated.

4. Conclusion

After recalling what the Bell’s inequality and the experimental measures are, the violation of this inequality appears to have been obtained by processing from a wave function property and the experimental conditions, but

have obscured the measures themselves. By treating these measures from the definition of  (average sum of

(average sum of ), Bell’s inequality appears to be respected. The ways of the two arguments are summarized in flowcharts.

), Bell’s inequality appears to be respected. The ways of the two arguments are summarized in flowcharts.

This article is limited to the demonstration of the violation of Bell’s inequality. It is neither a criticism of Bell’s inequality theory, nor of its consequences.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Pr. Roger BOUDET for his encouragements and help in the diffusion of this paper, Pr. Claude DAVIAU for his critical reading, and the referees for their valuable suggestions.

Appendix

A1. Bell’s Inequality

Let us remind the evolution of Bell’s inequality.

The inequality that Bell derived can be written as:

(29)

(29)

where  is the correlation between measurements of the spins of the pair of particles and

is the correlation between measurements of the spins of the pair of particles and ,

,  and

and  refer to three arbitrary settings of the two analysers [11] .

refer to three arbitrary settings of the two analysers [11] .

Generalizing Bell’s original inequality, it has been introduced the CHSH inequality, without any assumption of perfect correlations (or anti-correlations) at equal settings

(30)

(30)

where  denotes correlation in the quantum physicist’s sense: “the expected value of the product of the two binary (+/−1 valued) outcomes... the CHSH inequality reduces to the original Bell inequality” [11] .

denotes correlation in the quantum physicist’s sense: “the expected value of the product of the two binary (+/−1 valued) outcomes... the CHSH inequality reduces to the original Bell inequality” [11] .

A2. Average Quantum Sum

Let us call “the average value of ”:

”:

cf. Equation (8)

cf. Equation (8)

(31)

(31)

the average value of

the average value of  is “the algebraic sum of the four average values corresponding to the measures” [7] , which is mathematically transcripted by:

is “the algebraic sum of the four average values corresponding to the measures” [7] , which is mathematically transcripted by:

cf. Equation (9)

cf. Equation (9)

Demonstration:

cf. Equation (31)

cf. Equation (31)

so

(32)

(32)

(33)

(33)

and so

cf. Equation (9)

cf. Equation (9)

So , average value of

, average value of , is effectively the algebraic [quantum] sum of the four average values. It is an equivalent definition.

, is effectively the algebraic [quantum] sum of the four average values. It is an equivalent definition.

A3. Experimental Measures

Let us translate these synthetic measures through examples.

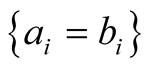

a) If the two polarizers are oriented in the same direction, the two photons always behave the same way (transmitted or absorbed depending on the angle of the polarizer with the polarization):  in all cases (Table A1).

in all cases (Table A1).

b) If the two polarisers are inclined at an angle of 30˚ with respect to each other, then the two photons have exactly the same behavior in 3/4 cases and in opposite fourth cases:  in 3/4 cases (Table A2).

in 3/4 cases (Table A2).

c) If the two polarisers are inclined at an angle of 60˚ with respect to each other, then the two photons have the same behavior in exactly 1/4 cases and in opposed 3/4 cases:  in 1/4 cases (Table A3).

in 1/4 cases (Table A3).

Table A1. Experimental measures with an angle of .

.

Table A2. Experimental measures with an angle of .

.

Table A3. Experimental measures with an angle of .

.

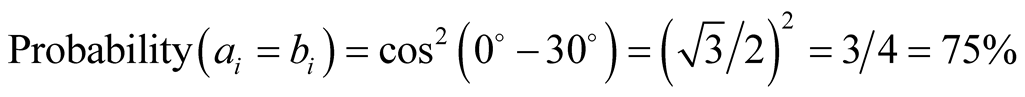

More generally, the probability that the behavior of photons to be identical is

(34)

(34)

with  the relative angle of the two polarizers.

the relative angle of the two polarizers.

a) When ,

,

(35)

(35)

b) When  and

and ,

,

(36)

(36)

c) When  and

and ,

,

(37)

(37)