Partnering with Batswana Youth and Families for HIV and AIDS Prevention ()

1. Introduction

1.1. HIV and AIDS in Sub-Saharan African

Sub-Saharan Africa has been hard hit by the HIV and AIDS epidemic and yet it is home for less than 10% of the world’s population. According to UNAIDS Report [1], 68% of the world’s adults and 90% of the world’s children living with HIV/AIDS are in Sub-Saharan Africa, which also accounted for 76% of global AIDS-related deaths [2]. Demographers and epidemiologists have debated for decades what may explain the vastly different HIV epidemic seen across the globe and reasons why Sub-Saharan Africa, where transmission is mostly heterosexually driven, has been so devastated by HIV. Plausible explanations may include high rates of other sexually transmitted infections that facilitate HIV acquisition and transmission, poor access to quality health care, insufficient or ineffective primary prevention programs, poverty, and engaging in behaviours associated with increased risk such as alcohol use and the practice of having multiple and concurrent sexual partners [3-5].

1.2. HIV and AIDS in Botswana

Botswana is one of the countries most devastated by HIV and AIDS epidemic in the world [1,6-8]. According to the Botswana AIDS Impact survey [9], the national HIV prevalence stood at 17.6% (20.4% for females and 14.2% for males). Similarly, the incidence rate follows the same pattern being higher in females (3.5%) than males (2.3%). Incidence rate is also higher in urban (3.4%) than rural areas (2.3%).

1.3. Rationale for the Study

The government of Botswana committed the nation’s resources to fighting the AIDS pandemic. It has been exemplary in implementing programs to mitigate the impact of the epidemic such as Prevention of Mother To Child Transmission (PMTCT), Voluntary Counselling and Testing (VCT), universal access to Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy (HAART), Isoniazid Preventive Therapy (IPT), HIV education and recently safe male circumcision. Despite these extensive efforts to combat the epidemic, behavioural change has remained the most difficult area to make any headway. HIV and AIDS education and information has been provided to all sectors using a multi-sectoral approach [10] and the Ministry of Education Skill and Development has been instrumental in the provision of Life Skills curriculum in public schools throughout Botswana [8]. However, a recent evaluation found that the Life Skills curriculum has not demonstrated any consistent effects on sexual behaviours and had no effect on biological outcomes [11-12]. Other existing primary prevention programs emphasize information dissemination and program evaluation confirmed that knowledge alone does not yield protective behaviour changes [7,13].

This current study aimed at adapting an evidencebased program, BART, (Being A Responsible Teen) originally developed and tested in the US for Batswana youth and to parallel the adolescent program with a parallel intervention for their parents. This study is undertaken through collaboration between the University of Botswana and Mississippi State University, funded by the Institutes of Mental Health. Overall, the current youth and family HIV prevention project has three phases: 1) a qualitative phase to tease out cultural contexts and opinions about the need for a primary prevention programme; 2) separate surveys of adolescents and parents to evaluate the psychometric properties of possible evaluation measures and assess the prevalence of risk behaviours and family communication patterns; and 3) adaptation and a pilot test of youth and parents programs in the intervention phase.

This paper describes the results of qualitative data gathered from youth, parents, and key informants to inform the intervention adaptation and revisions to the measures. Suggestions for intervention delivery gathered from the data will as well be used to inform adaptation of the original BART program for Batswana adolescents.

2. Methods

In-depth qualitative interviews gathered participants’ perspectives on the risk behaviours that youth (13 - 18 years) engage in and their types of relationships, how youth and their parents communicate on sexual matters, and views regarding adaptation of a youth prevention programme. The study triangulated data from the youth themselves (n = 40; 1/2 boys and 1/2 girls), parents (n = 40; 1/2 mothers and 1/2 fathers) and 20 key informants (primarily guidance teachers and youth officers). Three interview guides were developed, one for each group. Separate consent forms were developed for each category of informants. An assent form was developed for youth, whose parents also had to provide consent for their children to participate in the study. Once parents consented for their children participation, the assent form was then signed by youth. The participants were given information about the study and their rights of participation that was merely voluntary and they were free to withdraw at any point if they did not wish to continue.

Youth participants and key informants were recruited through schools and youth centres. Some parents were recruited through their children; while others were recruited conveniently using snowballing. The University of Botswana and Mississippi State University IRB boards and the Botswana Ministries of Education Skills and Development and Ministry of Health respectively reviewed and approved the protocol. Some questions that were asked to gather data from youth, parents and key informants included: What are the situations that put boys and girls at risk of STIs, HIV or pregnancy? What are the places where Batswana youth socialize? Which of these places expose youth more to risky behaviours? What drugs and alcohol are used by young people? Who do adolescents get into sexual relationships with? To what extent do you think adolescents who are sexually active use condoms? To what extent do sexually active adolescents have multiple concurrent partners? To what extent do adolescents communicate with their parents or guardians about sexual issues or STIs and HIV? What are your suggestions of how youth can be helped to avoid or reduce risky behaviours? In what ways can our program promote abstinence? What are the risky behaviours the program should address?

3. Results

Overall, the qualitative findings of this study indicated that youth of both sexes engage in risky sexual behaviours that could predispose them to contracting STIs, HIV infection and resultant teenage pregnancy. Youth also imbibe a lot of alcohol, use drugs, most commonly marijuana, and engage in unsafe sexual relations. Sexual initiations from sugar mommies and sugar daddies were common and perceived by youth as a means to acquire desired goods such as cell phones, cash, and clothes that their families could not afford.

3.1. Demographic Information

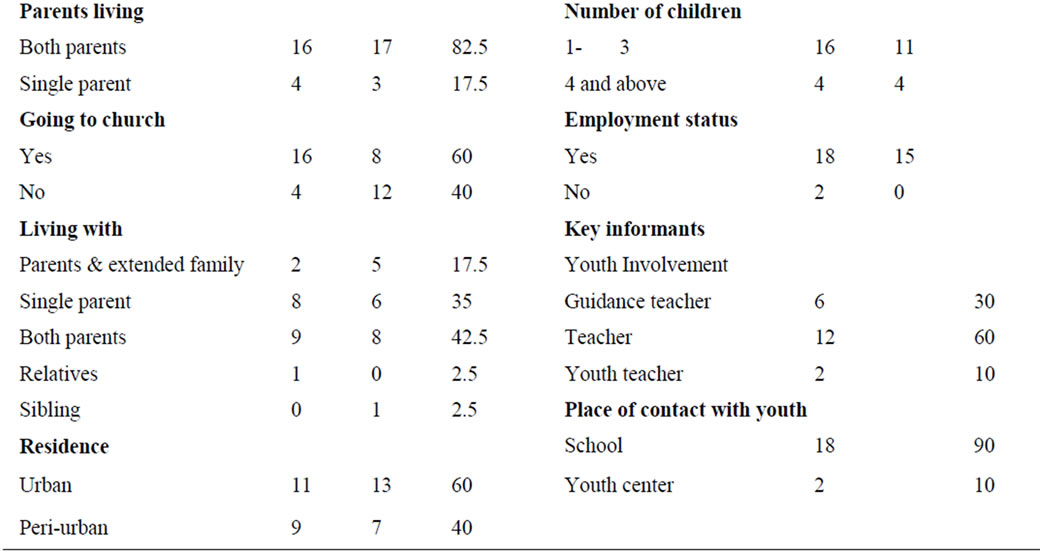

Youth participants were between 15 - 18 years with the majority in junior and senior high school, most attending public schools. About 80% of the adolescents had both parents still alive and 85% lived with at least one parent. Fifty percent lived in Gaborone while the rest came from neighbouring villages. Only two youth were out of school and one was at tertiary institution. Parents’ ages ranged between 33 to 50 years. Many of the parents had attended tertiary institutions. Table 1 below details the socio demographic information of the participants of the study.

3.2. Risk Behaviours

Common behaviours that predisposed youth to risks included drinking alcohol obtained from bars, night clubs and at parties. House parties are very common among this age group, typically taking place in their homes when their parents are absent.

Table 1. (a) Characteristic for youth n = 40; (b) Characteristics of parents and key informants n = 40.

Male: age 17: When they [parents] leave for meetings like for the whole week, they will give you money to buy small things for the house, but instead we use this money to organize house sessions [parties].”

House parties (“sessions”) are occasions to drink prior to engaging in sexual intercourse. Several participants described using house parties where a girl would deliberately be intoxicated until she passed out, after which a number of boys would all have sex with her.

Male, age 19: “We don’t just arouse them we even go to the extent of having sex with them when at these parties. So when we drink knowing that later on you will be into sex or other staff, you drink to a certain limit to be a able to do things later on At times girls [who have blacked out] are abused when they are in that sort of state and… it’s done without agreement and by so many boys in one girl…”

Mozwanes were also commonly reported when youth would hire a venue at a lodge or a combi (mini bus) and go out to the bush where they were free to drink, dance, and ultimately have sex. The types of alcohol commonly consumed include wines, spirits like vodka, and ciders such as hunter’s gold.

Youth are informed about a house party or mozwane through Facebook, personal communication, text messages, or pamphlets announcing the event that are distributed to others at school.

Male, age 19: “I face book. Either they send me an invite via message, text or they tell me verbally, or give a hand out pamphlet gore [that] this is what is happening through the weekend.”

The most commonly used drug is dagga (marijuana). Although the use of cocaine, methamphetamine, and ecstasy are rare, some youths reportedly used them. These drugs are also called by names that disguise their identity, for example marijuana is called “zolo”. (“Zolo” refers to any wrapping of tobacco or a cigarette.) These drugs are obtained from street vendors who will sell drugs only to their regular customers. These vendors who sell drugs have peculiar characteristics to identify them to their regular customers.

Male, age 19: “… every corner I go, everywhere I go, whether I go to Map School, or Mogodit Mogoditshane or Tlokweng, I will always find it. I always know where to find weed.”

Asked where youth get the money to buy alcohol and drugs, they said, parents give their children money to buy basic necessities such as clothes and they divert it to the purchase of alcohol and drugs.

Female, age 16: “… parents give their children money thinking that they would use it for something whereas they use it to buy alcohol.”

Parents and key informants were aware that youth use drugs and alcohol.

Female parent, age 43: “I hear about drugs such as cocaine but the drug that is commonly used from long time ago in this Botswana is marijuana. Just like they found alcohol being used from long time, marijuana had been used as well. The modern types of drugs like cocaine I really do not know where they get these”.

Teachers stated that these drugs are even brought onto the school premises. Some youth are given drugs by their parents to sell in school. Students are not permitted to leave school grounds during normal hours, but still they use alcohol and drugs during breaks and sometimes ask to go to the bathroom just to smoke. Some students arrive at school inebriated. Substance use was reported to affect adolescents’ behaviours in school, leading them to misbehave and sometimes become uncontrollable. The key informants reported instances where students under the influence of alcohol or drugs have beaten fellow students and teachers. They may also engage in petty stealing or become truant. Peer pressure is a factor in initiating as well as in maintaining alcohol or drug use.

Peer pressure at this age is very strong and the youth described the factors that will influence them to go along with a peer’s urging to engage in a behaviour as being a function of wanting a sense of belonging to a group, acceptance by peers, giving in to maintain status among their peers, or because a behaviour is perceived as reflecting either maturity or a certain social class Female, age 16: “Yes, when they see their friends drinking alcohol they do that in order to be part of that social group.”

Male age 17: “When I was young and then my friends started, I found out [that] they are doing it and I started to try it.”

Parents are aware that their adolescents will experience pressure from their peers to use alcohol and drugs.

Female parent, age 43: “They experiment, I will give an example, some drink alcohol and other kids like what they do and they also begin to drink. This can put others in danger.”

3.3. Multiple and Concurrent Partners

Multiple and concurrent partnerships are common among youth. These different partners have specific roles and meet different needs. One partner may be responsible for buying groceries, another for clothes and still another for transport, depending on how many partners a person may have. The motivation for having multiple partners basically rests on obtaining material goods and gifts.

Female, age 16: “Some they want to use them for different reasons... Maybe you have 5 boyfriends so they supply different materials, that the other one loves you and the other one buys you clothes.”

3.4. Intergenerational Sexual Relationships

Intergenerational sexual relationships are rife among both girls and boys alike, although they are more common amongst girls than boys. The reasons for these relationships center on obtaining material goods from the partners such as phones, clothes or in the case of teachers providing sex in exchange for a higher grade.

Female, age 19: “People of my age, I think they are like, they are getting in the multi and concurrent partnerships at a higher rate. Because people are after money, they are after fancy things, and if my father can’t buy me a C3 (Nokia) then I’ll have to find a sugar daddy who will buy it for me, because my other friend has the same phone, and I also want it”.

One youth had this to say about sugar daddy and sugar mummy syndrome:

Female, age 16: “Aaaa, most of them are aiming to get goods like phones, so that when they are seen in school using expensive things like phones they would be portrayed as living a high life. And others they go to an extent of seeking love maybe compensating for love that is lacking at home as in a father not being there. Some students are really disturbed and abused because they miss school because the sugar daddies sometime lock them inside their houses, they beat them and some fall pregnant.”

This suggests that at least some youth recognize that they are being confronted with a choice between shortterm gratification and risk of longer-term negative outcomes.

In contrast with many youths’ perceptions of intergenerational sex as a normative means of obtaining desired goods, some youths and most parents do not condone intergenerational sexual relationships.

Female parent, age 39: “Hei it’s not right… very not right for the children. Because I said previously I think somebody should be doing something because if they are really informed and they could make proper decisions. But if an elderly person now starts using a smaller one you know our thinking is not the same; with elders or sugar mummies or daddies they have different agendas in their lives, they want to attain something out of the children and on the other hand they might be destroying the children’s lives.”

Female parent, age 35: “No. It is not proper that young children like that should have sex with older people to bring food home. Adults who use young people in these kinds of things should have serious steps taken against them such as being arrested. They entice young children by buying them stuff and lure them by giving them money and things like that.”

3.5. Parental Monitoring

Youth, key informants and parents revealed problems and inconsistencies with regard to parental monitoring. While some parents impose curfews on their children; others do not bother to know where their children are or who they are with. Some parents have relegated their responsibility to the teachers. Some parents have challenges in their own life situations with regard to work schedules that do not allow them to adequately monitor their adolescent children such as working as a night watchman. Some parents blame life situations that put them in conflict with work or social commitments that interfere with their ability to fully execute their parental responsibilities. For example, during the course of the week many parents are at work and on weekends, they attend to their social responsibilities in the villages. Other parents do monitor their children and know their whereabouts.

Female parent, age 45: “Most of the time I know where they are and when they will be home. Where they go with whom? I know who they go to church with and whom they leave the church premises with. I call the people they tell me they will be with just checking if indeed they are there.”

Some parents interpret monitoring their children as policing them. They trust that children always mean what they say and believe them when they tell them what they do.

Female parent, age 49: “Mine is just talking. I don’t police. I don’t police them. I don’t police him. If he says he is going to the movie. I take it that he is going to the movie and I believe him. So, I don’t police. No. there are no… there are no… rules. The rule is you know you should take your key, so that when you come you do not wake anybody up to open for you.”

Other families have no family rules regarding informing parents where they are going, who they are with or the expected time for return.

Male parent, age 53: “I have no idea what they do when they go out with their friends, I think they talk what else they do, he isn’t talking [about it].”

Despite the freedom youth experience in the absence of parental monitoring, they endorsed the structure and accountability that parental monitoring provides. For example, one youth who indicated he was free to come and go at will said:

Male youth, age 19: “Parents should know where their kid is and with whom.”

3.6. Parental/Adolescent Communication

Most parents and adolescents reported that parents do not communicate with their adolescents about sexual matters and youth are hesitant to talk with their parents as well.

Female, age 19: “Generally, I don’t think youth talk to their parents about sex or stuff. Again some parents are not that open to talk their children, and that makes young people to refrain from talking to them.”

As a result, youth hear about these matters first from other sources such as friend, media, teachers at school, or health workers. Even when their source of information is someone like a teacher, the message they receive may not be appropriate.

Male, age 19: “At junior school our teacher used to tell us that sex is so nice.”

Despite the lack of family communication about sexual issues, young people expressed a desire to hear about these matters first from their parents. Female youth preferred to hear first about these matters from their mothers.

Female, age 19: “My mother, I would like to be taught by my mother not someone else.”

Fathers indicated that they were very uncomfortable talking to their daughters about sexual matters, preferring instead that mothers to talk to their daughters about issues of sexuality. Girls expressed the same sentiment, indicating that they would equally not be at ease to talk to their fathers about these matters. Parents and adolescents alike agreed that they found it difficult to discuss sexual development and sexual behaviour within the family.

Female parent, age 45: “It is difficult to talk to the children about boy friend and girl friend issue because even us the way we were brought up these things were not to be talked about so it is hard.”

Female parent, age 49: “I will be able to talk about everything; how a condom is inserted and how you go about it and all that freely, but if my child is there I will have a difficulty.”

Some parents reporting compromises with other family members to enlist their help in talking with their children about sensitive issues. In other cases, siblings agree on exchanges with each parent talking with the other parent’s children.

Female parent, age 43: “I don’t know… these things. I don’t know and sometimes they know the funny things; my relative will use me to talk to their children and to them it’s not a problem for me to talk to them; but sometimes then I see it as a challenge to talk to my own son. And I think I just said to my sister because she is a counselling teacher. So, I said because I am failing she should help this one my son and I will help you the other side. So that’s how we complement each other on these matters.”

Parents’ level of education did not enable them to discuss sexual issues with their children. No matter what their level of education, they still did not feel free or comfortable to discuss these issues with their children. The following quotation is from a parent with a Master’s degree and she had this to say:

Female parent, age 43: “I have the wish; but I don’t know which words to use… that’s my issue especially with the boy. Ene (him) my boy… am like I don’t know… I don’t know how… it becomes, to me… it’s a big challenge… but I still believe the little that I need to say I continue to say to him. How does he know about the changes in his life I asked, in his bodies I asked, what happens, and if those changes occur to him. How does he continue living with those and we chat about it we’ll, will be a little bit shy at the beginning but at the end he tells me what he knows and clear the conceptions at least with the knowledge I have.”

Mothers find it more comfortable to talk to their girl children than boy children. The girls seem to be more open and can ask questions pertaining to these issues than boys. However, overall, most parents indicated they found such conversations difficult, felt unprepared in how to talk with their children about sexuality, and parents and children alike tended to avoid such discussions.

There are, however, a few parents who are able to talk to their children about sexual issues. In most instances the discussions focus on the dangers of engaging in sexual relationships which youth perceive as threats rather than interactive educational discussions. One key informant noted these discussions are sometime in the form of remark and not educational. It was felt that parents pass bad remarks and threats at their children rather educating them.

Female parent, age 44: “I tell him that a child does not engage in sexual relationships but waits for the right time to do those things and the time when he starts him and his partner should check themselves first before having sex to see if they are okay. I also encourage him not to drink alcohol and smoke.”

Female parent, age 49: “Yes. We talk about anything… But other thing I feel that his father is the one who should talk about because he is a man. But this other general things we talk about anything. Generally, we only talk about, girlfriends blaaa bla. aa; bodily changes… those ones that I don’t want to talk about I ask the father to talk to him about I think he is the right person, because he went through those”.

3.7. Attitudes toward Adapting and Delivering a Primary Prevention Programme

Youth, key informants and parents were in agreement that something needs to be done and showed a high level of endorsement for a youth intervention prevention programme. It was believed that a health promotion program must entail health education and address communication between children and parents. The programme suggested by the researchers was seen as a very good initiative that could assist young people to reduce their level of risk. Parents expressed a desire to also be involved in a similar program so that they would be able to advise their children. Some argued that health education pertaining to HIV and AIDS issues has concentrated on the youth to the exclusion of parents and they felt that parents must be taught about these issues as well.

Female parent, age 45: “So, you concentrate on children what about us parents? Are you going to teach us also?”

Female parent, age 42: “… so that we are able to give advices when we are together.”

Young people stressed that the programme should be interactive and interesting to entice youth to attend it, because if it is not they will not attend. Some youth participants sad this about this program:

Female, age 16: “I think [that having a program like this one] these cases of teenage pregnancy, HIV/ AIDS would reduce in youth because like I said obviously youth will talk and listen to each other and realize the good and right way of dealing with this issues since they are willing to listen or take advice from one another.”

Female, age 16: “The way you approach like it if you come to them and talk about HIV/AIDS they get turned off so at least come with a bit of energy and jokes so that it becomes fun. Because if you are boring we don’t attend it. The way you advertise it, make it eye catching so that people should ask themselves what are these people talking about it... and if fliers make them eye catching.”

Overall, parents, youth, and key informants felt that such a programme would provide an opportunity to teach the youth about the consequences of being infected with HIV and give them information and empower them on how to abstain.

Female parent, age 42: “Eemmmh, there is a need because today life is different from the way it was in the olden days. If you compare children from the olden days they lived a protected life as compared to nowadays, so I believe there is need for such a program.”

Parents were positive about having the proposed program for their children and felt it was acceptable to address correct condom use.

Female parent, age 49: “It is important that they are taught about the dangers of this illness HIV and AIDS and that they should be encouraged that all the time to use condoms if they have already started engaging in sexual relationships.”

Participants identified very specific content they would like to be included in the programmes. They wanted the program to include information and skill building, but both parents and adolescents also wanted the program to address communication, social and emotional issues associated with adolescent sexuality to ensure that they would have the knowledge and skills, and that they feel comfortable and confident to talk about sexual issues. They also felt it was important that the program address the risks associated with use of alcohol and drugs. It was interesting to note that there was no disparity between the content suggested for youth and parents by either group. Both parents and their children were eager to participate in a program that could assist them in addressing these issues within the family.

Finally, interviewees were asked for their suggestions about locations, days and times when such a program should be offered. The University of Botswana was mentioned very often as the preferred venue for the programme. However some youths thought schools would be good venues for the programme because that is where more youth are to be found. Key informants who were mostly guidance teachers, on the other hand, preferred a neutral venue such as the University of Botswana or a church rather than schools. The latter was seen as not user friendly for such a programme because it is associated with punishment and discipline. They felt that sexual and behavioural risks should be discussed in a level setting where there can be free discussions without concerns about intimidation and apprehension.

Female parent, age 49: “For parents heii… for parents weekends it’s very difficult. Because, the issue is time, there are funerals, weddings again during the week when they finish work but we will be doing one or two days a week. During the week after work is okay. It is because parents are diverse they cannot just go in one place… so, for parents it will be better to call them at one place… like UB… or church.”

There was variability in parent’s preferences regarding a suitable day for the program. Some preferred a weekday, while others preferred a weekend and all give sound reasons for their preference. Those who preferred Wednesday stated it was because it was mid week and there was not much school work. Some felt that weekends would not be good, yet others felt that weekends would be ideal because that was when youth do not go to school and were available. Some preferred the weekend because they recognized this was the time when the youth indulged in “bad things” and this programme could take them away from doing these things. Fridays were considered days that most adolescents could be available and the days on which they are looking forward to going to do “bad things.”

Female parent, age 38: “... it is a day which most adolescents always look forward to, to go and do bad things so this day will be suitable for them to get disturbed from doing bad things and instead it will be a day for them to get advices.”

All the adolescent girls strongly supported that parents should also be provided with this or another program and be taught about HIV because it infects everyone. The sentiments expressed about why parents have to be taught were as follows:

Female parent: “They should be taught about HIV because HIV infects everyone information can be useful to them?”

Female parent: “The parents have to be talked to, so that they are able to talk to their children. They should know what to talk to their children about.”

Surprisingly, both parents and adolescents expressed positive attitudes toward attending sessions together as long as they can be introduced to the issues separately first and then later be brought together. The parents wanted to acquire basic information and skills prior to combining them with the youth.

Female parent, age 43: “I would think after introducing the issues with the parents differently and differently with the children then, attending together with the children can still work. Because we will all have baseline information, we will have like the same level of understanding, both of us at different times. Because as parents we talk differently will talk differently with them; but we still need a forum a where we meet… ee.”

4. Discussion

Young people in Botswana today live in times that are trying and unpredictable where the possibilities of acquiring an HIV infection, falling pregnant or developing alcohol or drug dependency are very high [14]. Youth, especially girls, are enticed into transactional sexual relationships with older people commonly known as sugar daddies and mummies. Young people are usually financially and materially motivated to engage in these types of relationships. They receive gifts, money, clothes food, cosmetics, cash and clothing and other resources in exchange of sex) [15]. These relationships come with varying levels of commitment because in most instances these sugar dads and moms are engaged in relationships with other partners and will not invest in their relations with young people [16,17]. In addition, due to power imbalances and also the transactional nature of these relationships, the youth may not be able to negotiate safer sex, thus they are at risk of HIV and other STI infections [15,18,19].

Multiple and concurrent partnerships are also rampant in Botswana and it is particularly a risky behaviour motivated again by youngsters seeking material and financial support. These many partners are assigned roles and responsibilities to take care of difficult needs that adolescents have. Multiple and concurrent partnerships put young people at risk of teenage pregnancy, HIV infection and other STIs [20] and uneven power dynamics [16].

Poor parental monitoring was another concern to emerge from this study. Some parents were not just concerned to know where their children were and who they hang around with. Situations like these encouraged adolescents to engage in risk behaviours which could predispose them to contracting HIV and AIDS. It has also been found that generally there is poor communication within families regarding sexual issues and HIV and AIDS. Parents find it very difficult to discuss sexual matters with their adolescents and in some cases they are punished for raising the subject. Parents do this so as to control their adolescents’ sexual activity [21].

The most concerning findings to emerge from this qualitative research was the extent to which youth are engaging in risky sexual interactions often preceded by the use of alcohol and drugs, especially at house parties and mozwanes. It was evident from the interviews that parents shy away from discussing sexual matters with their children, especially if they are of the opposite sex. Mothers stated that they do not feel comfortable in talking to their boy children. Similarly, fathers were not comfortable in talking to their girl children. The most common response from both parents and adolescents was to indicate that these types of conversations did not take place within the family. Without having someone in the family prepared to talk to their children about such matters these leaves children with no option but to learn about sexuality and sexual safety from their peers, media, and teachers. Interestingly, the youth expressed a strong preference to learn about such matters first from their parents. Most sexual communications that were reported between parents and children revolved around telling the youth what not to do and the dire consequences of what will happen if they engaged in such acts. This information is often presented in a manner that is threatening and frightening. Therefore there is a communication gap between parents and children that both generations felt should be addressed. Given youth’s expressed desire to learn about sexual issues first from their parents and parents desire to learn how to talk with their children about such sensitive issues, teaching parents to feel comfortable, confident and knowledgeable about topics and issues of sexuality clearly would be very beneficial for them. As a consequence of these findings, the planned youth prevention program will now be paralleled by a program for their parents, with some interactive sessions that include both parents and their adolescent children after each is provided with basic information-provision and skill-building in their respective programmes.

5. Conclusions

The findings of this study showed that prevalence of HIV related risk behaviours among adolescents is high and continues to grow. The risks include drinking of alcohol, drug use and abuse especially marijuana, multiple and concurrent partners, sexual relationships with older partners, poor parental monitoring and poor parent and adolescent communication.

Several factors have profound influence on these risks have been identified. The most intricate one is the limited communication between the parents and their adolescent children on sexual matters. There is a need for interactions between parents and their adolescent children to be cultivated and enhanced so that both parties can feel more comfortable and confident to hold conversations on such issues. The study will culminate in adapting an HIV prevention program that was developed in the US for implementation in Botswana to provide both youth and their parents with support and guidance in dealing with sexual issues.

6. Acknowledgements

We express our thanks to the study participants: youth, parents and key informants alike for sharing their candid views and providing insights into the envisaged health promotion programme. Our gratitude to the NIMH for providing funds that enabled us to conduct this research (#R34MH092199). We also appreciate the University of Botswana and Mississippi State University for providing other supportive resources such as technical assistance, equipment and space and to all of those who took part in transcription and translation of the interview data.