Cross-sectional population based study ascertaining the characteristics of US rural adults with mental health concerns who perceived a stigma regarding mental health issues ()

1. INTRODUCTION

An estimated 50% of adults in the US will develop at least one mental illness during their lifetime [1]. Studies show mental illness can impose a significant burden. According to the World Health Organization mental illnesses accounts for more disability than any other group of illnesses [2]. Mental illness has been associated with a number of chronic diseases. In particular, depression has been associated with chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease, arthritis, asthma, and diabetes [3]. Not only are individuals’ quality of life affected but there is also a significant monetary burden to the individual and the community. It is estimated that mental illness costs the United States $317 billion each year from lost wages, disability payments, and medical care costs [4].

Despite the disease burden of mental illnesses, one study found that only 36% of US adults with mental illness received healthcare treatment in the course of a year [5]. There are various reasons for not seeking care and stigma has been shown to be one such barrier. The 1999 US Surgeon General report regarding mental health offered that stigma associated with mental health may be the reason why nearly one-half of those with a mental illness in the US do not seek treatment [6]. Looking at depression specifically, individuals with greater depression severity have been found to experience greater stigma [7]. Unfortunately, even those who do seek treatment may be negatively affected by stigma. For example, greater perceived stigma has been associated with decreased adherence to antidepressant medications [8].

Rural communities are a particularly vulnerable population in relation to mental health and mental health care [9]. Rural populations are already at increased risk for health disparities [10]. It has been shown that there is a shortage of mental health professionals in rural areas; approximately 85% of Mental Health Professional Shortage areas are in rural communities [11]. Along with a shortage of qualified professionals, it has been reported that residents of rural communities may also experience greater levels of stigma in relation to their mental illness, in part due to a lack of anonymity and privacy [12,13]. When compared to non-rural populations, rural residents have been shown to be more likely to begin treatment later in the course of mental illness, resulting in more severe and persistent symptoms and ultimately greater treatment expense [14].

While various studies have shown the role stigma plays as a barrier to mental health care especially in rural communities, few studies have sought to characterize the populations most affected by mental illness stigma. This study sought to answer the question: What are the characteristics of US rural adults with mental health concerns who perceive stigma regarding mental health issues?

2. METHODS

In 2007, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) surveyed adults in 37 states and territories about their attitudes toward mental illness. These data were analyzed using bivariate and multivariate techniques to answer the research question. BRFSS is the largest surveillance system in the world. It is a random digit telephone survey that is a collaborative project of the CDC and all US states and territories. The survey collects interview data from non-institutionalized US adults aged 18 through 99 years. BRFSS collects information on health risk behaviors, preventive health practices, and health care access primarily related to chronic disease and injury. BRFSS is constituted of core questions that must be asked of every survey participant and optional modules that may be chosen by individual states and asked only of the survey respondents from the participating state(s). A complex multi-stage sampling approach is used by BRFSS and subsequently a weighting factor is calculated for application to the data in order to ensure that they are representative of the US population based on the most recent census data. These methodological matters are described in greater detail elsewhere [15]. All analyses were performed on weighted data as is recommended by the CDC.

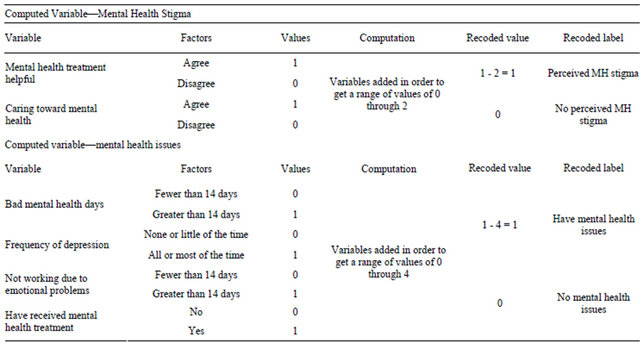

In the analyses presented here a number of variables were either re-coded or computed. All re-coding entailed collapsing categories and removing the responses don’t know and refused. Computed variables included mental health concerns, mental health stigma, and race/ethnicity.

To compute mental health stigma, the responses from two optional module questions were involved: 1) mental health treatment can help people lead a normal life, and 2) people are generally caring toward people with mental illness. A Likert-type scale was used in constructing the response categories for both questions/variables. These categories were re-coded as either Agree (coded as 1) or Disagree (coded as 0) and then merged. The re-coding entailed collapsing the original response categories. The merging entailed adding the two variables together.

The computed variable, mental health concerns entailed merging the responses from four separate survey questions/variables: 1) number of bad mental health days; 2) frequency of depression; 3) emotional problems kept you from work; and 4) receipt of mental health treatment. The response categories of each of the four involved variables were re-coded into bifurcated categories that were numerically coded either as a 1 or a 0. Table 1 displays the re-coding and variable computing strategy used in creating the two new variables.

The race/ethnicity variable was calculated from participant responses to two separate survey questions—one regarding race and the other regarding Latino/Hispanic ethnicity. All race/ethnicity categories were computed as mutually exclusive entities: Caucasian, African American, Hispanic and Other/multiracial. All respondents who chose white as their racial classification were coded as Caucasian; those who chose black as their racial classification were coded as African American. Respondents who chose other racial classifications including more than one race were coded as Other/multiracial. If a respondent identified themself as Hispanic or Latino they were classified by that ethnic category regardless of any additional racial classification.

This study used the Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA) variable included in BRFSS to define geographic locale as either rural or non-rural. MSA was re-coded by collapsing categories into those of rural and non-rural. Rural residents were defined as persons living either within an MSA that had no city center or outside an MSA. Nonrural residents included all respondents living in a city center of an MSA, outside the city center of an MSA but inside the county containing the city center, or inside a suburban county of the MSA.

For all statistical analyses, alpha was set at p < 0.05. Statistical Package for Social Scientists (SPSS, IBM, Chicago, IL, version 20.0) was used to complete all statistical analyses performed for this study. Human subject approval was sought and received from Essentia Health’s Institutional Review Board (IRB).

3. RESULTS

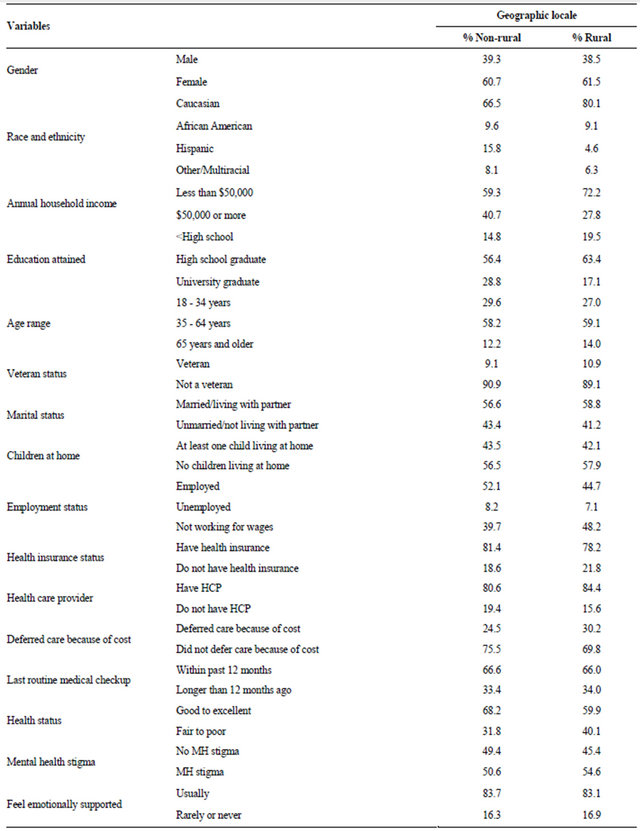

In comparison to non-rural US adults, rural adults had greater odds of having mental health concerns (OR = 1.128, 95% CI 1.127 - 1.129). Table 1 describes the characteristics of US adults with mental health issues by geographic locale (rural/non-rural). A higher proportion of rural adults compared to non-rural adults lived in households with an annual income of less than $50,000 (59.3% vs. 72.2%), while a significantly lower proportion of rural adults (17.1%) in comparison to non-rural adults (28.8%) were university graduates. Additionally, a higher proportion of rural adults (48.2%) were not working for wages compared to non-rural adults (39.7%).

Table 2 goes on to display differences in health care related circumstances between rural and non-rural US adults. In this regard, a higher proportion of rural adults (21.8%) in comparison to non-rural adults (18.6%) did not have health insurance. Furthermore, a higher proportion of rural adults (30.2%) deferred health care due to cost when compared to non-rural adults (24.5%). More rural adults also defined their health status as fair to poor when compared to non-rural adults (40.1% vs. 31.8%). Lastly, a higher percentage of rural adults (54.6%) perceived a mental health stigma in comparison to their non-rural counterparts (50.6%).

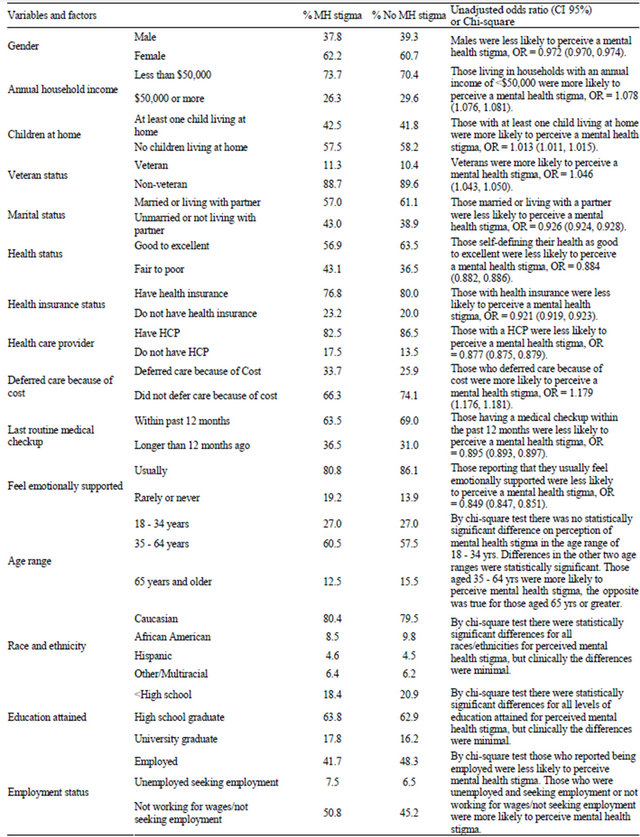

Table 3 displays the bivariate analysis of US rural adults with mental health issues who perceived mental health stigma. Adults with the following characteristics had greater odds of having perceived mental health stigma: living in households with an annual income of <$50,000, having at least one child living at home, being a veteran, and deferring care because of cost. Adults with the following characteristics had lower odds of experiencing stigma in relation to mental health: male gender, married or living with a partner, self-defining health as good to excellent, having health insurance, having a health care provider, receiving a medical checkup within the past 12 months, or reporting feeling emotionally supported.

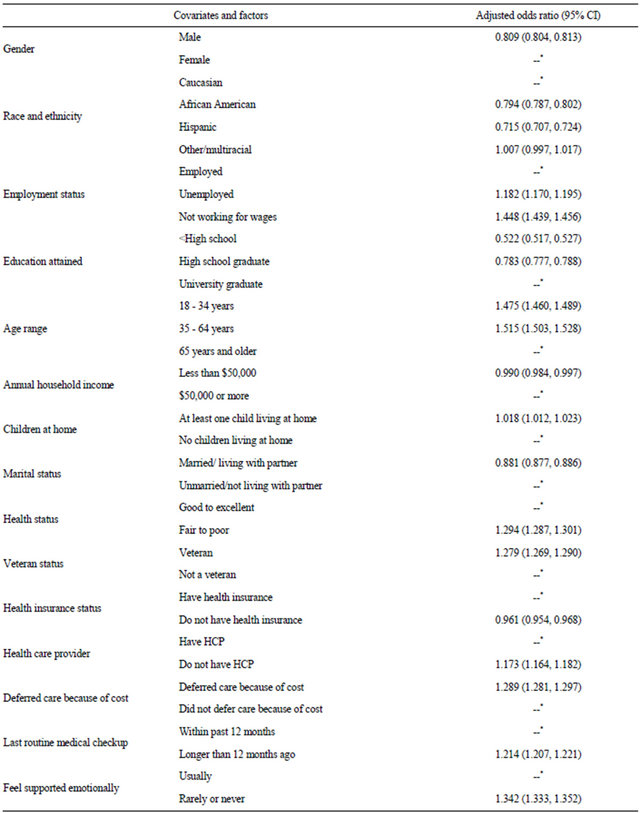

Table 4 displays the results of the multivariate analysis performed using perception of stigma as the dependent variable and rural US adults with mental health con-

Table 1. Computed variables mental health stigma and mental health issues.

Table 2. Characteristics of US adults with mental health issues by geographic locale 2007 BRFSS data.

Table 3. Bivariate analysis of us rural adults with mental health issues who perceive mental health stigma 2007 BRFSS data.

Table 4. Logistic regression analysis of rural adults with mental health issues perceiving stigma related to mental health 2007 BRFSS data.

--*referent category.

cerns as the population of interest. The logistic regression analysis revealed that rural adults reporting mental health concerns who perceived stigma regarding mental health were more likely to: be unemployed seeking work, be not working and not seeking work, be less than 65 years old, have at least one child living at home, selfdescribe health status as fair to poor, not have a health care provider, have not received a routine medical check-up within the past 12 months, rarely or never feel emotionally supported, be a military veteran, or have deferred medical care because of cost. Males, African Americans, Hispanics, those with less than a university education, those living in a household with an annual income < $50,000, those married or living with a partner, or those not having health insurance were less likely to perceive stigma related to mental health issues.

4. DISCUSSION

This study confirmed the findings previously reported that suggested rural populations perceive greater levels of stigma related to mental health when compared to non-rural US populations [16]. Our study further specified the characteristics of rural adults with mental health concerns that were more likely to perceive stigma related to mental health issues. For example, this study ascertained that rural military veterans were more likely than their non-rural counterparts to perceive stigma regarding mental health issues. The results also indicated that those with no primary health care provider, those with at least one child living at home, and those reporting feeling rarely or never emotionally supported were more likely to perceive stigma. Alternatively, rural adults with mental health concerns who lived with a spouse or partner were less likely to perceive stigma regarding mental health issues. These findings suggest that those adults in rural communities who have mental health concerns with a limited support system may be particularly vulnerable to perceiving a stigma regarding their mental health issues.

Other studies suggest the possibility that perceived stigma in relation to mental health might act as a barrier to mental health care [6,17]. Identifying those populations at greatest risk of perceiving stigma may help to determine groups also at greatest risk for the negative aspects of not receiving mental health care such as chronic disease, decreased quality of life and worsening mental illness.

While a number of concerted efforts such as educational programs and community contact programs have shown some success in decreasing stigma, further studies are needed to identify the most effective ways to decrease mental health related stigma perceived by individuals with mental health concerns, specifically in rural communities [18]. Corrigan, et al., (2012) reviewed outcome studies regarding methods of challenging mental health stigma and concluded that stigma is a local issue and that outreach should meet the needs of individual communities [18]. By identifying those most at risk for perceiving stigma in rural communities, efforts can be more appropriately directed and further individualized. Rural populations face unique challenges that their nonrural counterparts do not. The best approach to solving the problem of mental health related stigma in rural communities where health professionals most likely are scarce is yet to be determined. Pharmacists may help play a role in decreasing or identifying stigma particularly in rural areas where they are often the most easily accessible health care providers. Pharmacists can work closely with the members of their community and could play an integral role in developing methods of decreasing stigma that is customized for their communities. Pharmacists can become part of a patient’s support system as well as be a resource for educational information.

Study Limitations. There are limitations to this study. First, the survey questions pose a limitation, as the only variables that could be analyzed were those that were included in the survey. Second, the collected data may be skewed since they were collected via telephone and those who could not be reached by phone could not participate. For example, the common practice of using answering machines and caller ID allows people to filter their phone calls potentially leading to a passive refusal to participate in surveys such as BRFFS. The use of devices such as answering machines and caller ID to filter out “unwanted” or “unfamiliar” callers, however, is beyond the control of survey administrators. Finally, mental health concerns are sensitive and some study participants may have been unwilling to disclose their mental health issues resulting in an under reporting of the prevalence of such. Since only those adults self-reporting having mental health issues were asked the related questions used to assess stigma related to mental health issues, the actual perception of such stigma may also have been under reported. Nevertheless, this study does have strengths. Since we used population based data representing US adults, we had a large sample size. With a large sample size generalizable statements about the US population as a whole are more easily made.

5. CONCLUSION

In contrast to non-rural adults, rural adults with mental health concerns were more likely to perceive stigma in relation to mental health issues. Support systems emerged as a significant influence regarding the perception of mental health stigma. Specifically, support systems may render people with mental health issues less vulnerable to perceiving stigma, assisting with the removal of stigma as a barrier to care. Pharmacists could play a role providing support in communities and serving as an educational resource, especially in areas where they may be the most accessible health care provider.