Nature and Extent of Traumatic Experiences among Refugees in Dadaab Camp, Kenya ()

1. Introduction

Globally, there are currently almost 80 million forcibly displaced people, including 26 million refugees and over 4 million asylum seekers (Ziersch et al., 2020). These forcibly displaced people fled to various countries to seek refuge. Many factors have contributed to their journey. Specifically, refugees and asylum seekers flee their country because of persecution, war and/or violence and many are exposed to torture and trauma (Ziersch et al., 2020). A meta-analysis of 181 research of conflict-affected groups, including refugees and displaced persons, in the United States of America, New York, estimated that PTSD and depression are widespread at 30.6% and 30.8%, respectively (Nickerson et al., 2016). Refugees are often traumatized by conflict, persecution, and loss, with potentially traumatic events occurring both in the nation of origin and during the migratory process (Malm et al., 2020). In addition, indications of PTD and depression predicted difficulty with integrating (Schick et al., 2016). Torture was found to be a major indicator of mental illness, particularly signs of Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in refugees and other conflict-affected groups (Gottvall et al., 2019). Forced displacement episodes might last for a short time or a long time, depending on the original trigger (Siriwardhana et al., 2015). A common disorder in this scenario is PTSD, which is characterized by the presence of both mental and physical anguish, persistent pain and somatization, loss of self-regulation abilities, and difficulties with day-to-day functioning (El Sount et al., 2019; Gupta, 2013). The wide range of post-traumatic and post-migratory stress among traumatized refugees indicates an increased need for novel treatment strategies in health care systems to target both mental and physical health and to promote general health behaviour, daily life functioning, and psychosocial adjustment (El Sount et al., 2019).

Epidemiological studies have found a significant frequency of anxiety in eight conflict-affected districts from a nation-wide survey in Sri Lanka in Southern Asia, in a variety of post-conflict situations, depression symptoms, as well as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are the most widely examined mental health outcomes (Tay et al., 2017). As a result, psychiatric disorders were more prevalent among conflict-affected groups, and the aftereffects and symptoms of traumatic experiences could continue for years (Mahmood et al., 2019). War and its aftermath put a great deal of strain on the people who reside in those areas because of the uncertainty and the immediate harm that the fighting does to people, property, and livelihoods (Vaktskjold et al., 2016). Illness patterns shift and people require more medical attention (Vaktskjold et al., 2016). War refugees had up to ten times the rate of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as the normal population, according to Rawlinson et al. (2020). The number of refugees arriving in Ethiopia has already overtaken that of Kenya as the country is now home to hundreds of thousands of Eritreans, Somalis, and South Sudanese (Gebrehiwet et al., 2020). Traumatized refugees often have a long trauma history, have been raped or tortured, and have had family members die in the fighting. Psychological discomfort, such as acute stress reactions and grief, are linked to this in traumatized persons. In South Sudan, researchers conducted a cross-sectional community survey to better understand the link between trauma exposure and disability (Ayazi et al., 2013). Armed conflicts increase the number of disabled persons, and those with disabilities are more likely to be the victims of violence as a result of their disability (Ayazi et al., 2013). Mental illness and drug misuse were shown to be responsible for 13% of global disability-adjusted life years and 32% of global disability-adjusted life years (Noubani et al., 2020). When displaced, people with disabilities face additional challenges due to their vulnerability in conflict zones (Ayazi et al., 2013).

Studies show that people who have experienced war and armed conflict, as well as those who are poor, unequal, or face other social injustices, have much worse mental health and a higher prevalence of mental disorders (Bosqui et al., 2020). A cross-sectional research of depression frequency and associated factors among Somali refugees in Melkadida camp, south-east Ethiopia demonstrate psychological discomfort, psychosomatic complaints and clinical mental disorders such as depression and PTSD are more prevalent among refugees than other populations (Feyera et al., 2015). Depressed mood, loss of interest or pleasure, diminished energy, feelings of guilt or low self-worth, interrupted sleep or food, and impaired concentration were all symptoms of depression (Feyera et al., 2015). Widespread insecurity and increased poverty, coupled with lack of basic services such as healthcare, Education, water and sanitation, exacerbate mental health conditions (Slewa-Younan et al., 2017). Adult refugees in the Dadaab camp suffering from depression were treated with therapeutic counselling provided by counselling organizations (Nyaga et al., 2016). The mental disorders among refugees in Dadaab camp have been exacerbated by poor sanitation, inadequate mental health care, unemployment and poverty. In the Dadaab refugee camp, sexual gender-based violence has been identified as a significant issue in such a humanitarian setting. In addition to being a major violation of women’s human rights, sexual violence also poses a threat to their health and well-being, with a range of negative physical, mental, sexual, and reproductive health outcomes as a result (Capasso et al., 2021).

Conflict not only leads to higher mortality and morbidity rates, but it also gravely compromises already precarious health care systems by destroying infrastructure, driving out medical professionals, and disrupting the flow of pharmaceuticals and medical supplies (Belaid et al., 2020). Mental health and psychosocial support services (MHPSS) demand may surge as a result of humanitarian disasters due to the increased mental health demands of crisis-affected communities (Troup et al., 2021). It’s a situation like this that exacerbates mental health issues like anxiety, despair, and PTSD. It can also lead to somatization. Conflict can also have disastrous impacts on sexual and reproductive health, new-born health, mental health, and non-communicable diseases like cancer, hypertension, and diabetes (Ramos et al., 2020). Wars and military conflicts alter social conditions for the worse by increasing poverty, reducing employment, inciting violence in the community, and resulting in living conditions that are insufficient (Matanov et al., 2013). As a result of such traumatic exposure, they were terrified for their own safety as well as the safety of their loved ones, and they even witnessed the deaths of others. These psychologically upsetting occurrences cause a great deal of anxiety, despair, helplessness, and a lack of faith in the future (Munz & Melcom, 2018).

2. Theoretical Framework

This study was guided by the Refugee Theory. Refugees are people who are compelled to depart their home countries to avoid major human rights violations and other forms of long-term physical and emotional suffering. Trauma is caused by emotional suffering, physical illness, and psychological damage. In this regard, every day in various nations around the world, refugees’ basic rights are violated, and a rising number of refugees are exposed to disasters, tremendous trauma, and persistent physical, sexual, and psychological persecution. In addition, refugees confront a lack of autonomy in their host countries, where they are effectively powerless and seen as a threat. The impacts of trauma on refugees are unfathomable, long-lasting, and shattering to both their inner and exterior identities. The prominent creator of theoretical frameworks examines several perspectives on refugee experiences and strives to fill in the gaps by illustrating the interconnectivity of refugees’ experiences and the trauma they bring with them (Payne, 2005).

The framework of Refugees as proposed by George (2010), is used as a foundation for stressing refugee trauma as a result of many social and political restrictions entrenched in refugees’ personal experiences. Examining and connecting these theories in the context of refugee trauma yields a variety of perspectives on refugee trauma (George, 2010). The proponent of the Kinetic Model of Refugee Theory (Kunz, 1981) offers a wealth of information about refugees’ perspectives toward displacement (Collins, 1996). Most refugees’ flight and settlement patterns, according to Kunz (1981), fall into two categories: anticipatory refugee movement and acute refugee movement (Collins, 1996). Anticipatory refugees detect danger early, allowing them to flee in a safe and orderly manner before the crisis begins; as a result, they are frequently accompanied by their entire family, with all of their belongings intact, and have prepared for a new life (George, 2010). Anticipatory refugee theory places the state at the centre of the conflict causation mechanism: not only does the state instigate conflict, but it is also the cause that individuals are subjected to conflict. Anticipatory migrants flee as soon as a country is willing to take them in (George, 2010).

Acute movements, on the other hand, are reactions to a sudden and overwhelming pressure that forces individuals to flee their homes (George, 2010). They are unprepared for the voyage and are solely concerned with surviving the disaster area (Kunz, 1981). Because the implications of fleeing are rarely considered, there is a higher probability of a cute refugee encountering or witnessing traumatic events, and they are thus more likely to require assistance in coping with their difficulties (George, 2010). When refugees arrive to a place of asylum, they are faced with a difficult choice: return home, seek asylum at the place of asylum, or take another distant resettlement opportunity in an unfamiliar area (George, 2010). The proposed addition of the concept of new vs conventional refugees to the refugee theoretical framework greatly de-mystified the refugee theory (Paludan, 1974). New refugees are culturally, radically, and ethnically distinct from their hosts; they come from less-developed nations, and they are likely to lack kin and/or possible support groups in their new country of resettlement (George, 2010). Traditional refugees, on the other hand, are culturally and ethnically similar to those in the host nation, come from similar stages of development, and are more likely to be welcomed and aided by relatives and friends who understand their language and can help them acclimatize (George, 2010). Certain patterns of settlement behaviour are influenced by the variations between new and traditional refugees (Paludan, 1974). Anticipatory refugees are more likely to seek asylum in wealthy Western countries, where they will be treated as new refugees due to the resources they can bring with them (George, 2010). They also have fewer traumatic experiences and require less assistance than acute refugees who flee to countries with many of the same features as their homelands (George, 2010).

Kunz broadened refugee theory to incorporate the notions of majority-identified, event-connected, and self-alienated refugees (Kunz, 1981). Those who oppose social and political developments in their own country make up the majority of refugees (Collins, 1996). Because of active prejudice against the specific group to which they belong, events-related refugees are forced to flee (George, 2010). Self-alienated refugees are people who flee their native nation for a variety of personal reasons (George, 2010). Despite the fact that Kunz’s refugee theory pays little attention to refugees’ painful experiences in camps or throughout the settling period, His theoretical explanations enable care providers to detect unique behavioural patterns based on numerous refugee classifications, gain a better understanding of the history of their clients’ trauma, and devise effective therapies to deal with it (Kunz, 1981).

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

The researcher employed descriptive research design. Descriptive research designs a method of data collecting information by interviewing or administering questionnaire to a sample of population to get their attitude, opinion and habits on any variety of educational or social issues. This research evaluated the effect of conflict on mental health of refugees in post-conflict situation. In this case descriptive survey allowed the researcher to utilize questionnaires, interviews, focus group discussions guides and observations checklist as research tools.

3.2. Study Area

The study was conducted in Dadaab camp, Garissa County in North Eastern region of Kenya. Dadaab refugee camp is approximately 100 km from the border with Somalia (Polonsky et al., 2013). The choice of Dadaab camp was based on the fact that, it was the oldest refugee camp that is composed of refugees from various countries in Africa. According to UNHCR Mission Report (2013), Dadaab camp consists of five camps namely; Dagahaley, Ifo1 Hagadera, Ifo2 and Kambioos. The vast majority of the refugees (96%) were from Somalia, with most others from Ethiopia (UNHCR, Mission Report, 2013). As a results of deteriorating humanitarian situation caused by continued conflict in Somalia and by the failure of rains from October to November 2010, the number of Somalis seeking refuge in Kenya (and elsewhere in the region) has steadily increased (Polonsky et al., 2013). Figure 1 illustrates Dadaab Refugee Camp sites following closure of Ifo2 and Kambioos and relocation of refugees to Ifo1, Dagahaley and Hagadera as Functional Camps.

3.3. Study Population

Approximately, there were 235,265 registered refugees in Dadaab complex, all of

![]() Source: Researcher, 2019.

Source: Researcher, 2019.

Figure 1. Dadaab refugee camp sites.

them hosted in Ifo1, Hagadera and Dagahaley camps. United Nation High Commissioner for Refugees operational update report of 15th April, 2018 indicated that 58% of Dadaab population were children. Therefore out of 235,265 estimated registered refugees, 42% which was 98,811 total adult refugees formed the study population in Dadaab camp. The study also included 24 Key Informants from the government, INGOs and 16 traumatized refugees. Such was the population that formed the study target population in Dadaab camp.

3.4. Sampling Strategy

Approximately, there were 235,265 registered refugees in Dadaab complex, all of them hosted in Ifo1, Hagadera and Dagahaley camps. United Nation High Commissioner for Refugees operational update report of 15th April, 2018 indicated that 58% of Dadaab population were children. Therefore out of 235,265 estimated registered refugees, 42% which was 98,811 total adult refugees formed the study population in Dadaab camp. The study also included 24 Key Informants from the government, INGOs and 16 traumatized refugees. Such was the population that formed the study target population in Dadaab camp.

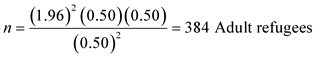

The study employed both probability and non-probability sampling techniques. The study applied the formula recommended by Fisher et al. to arrive at the sample size since the target population of the respondents for which the study was based on, was more than 10,000 respondents (Mugenda, 2003). The desired sample population size was determined using Fisher’s formula for sample size determination as cited in (Mugenda, 2003).

(when target population is greater than 10,000).

(when target population is greater than 10,000).

where, n = the required minimum sample size

Z = the standard normal deviate at the required confidence level = 1.96

P = the proportion in the target population estimated to have characteristics being measured

Q = 1 − P

d = the level of statistical significance set (0.05) in this study. Due to the fact that the study area covered by the target population was large, then the sample size of the study would be:

The sample population for the study was distributed as follows; 384 refugees obtained through stratified simple random sampling, 24 key informants purposively sampled, and 16 traumatized refugees by snowball sampling as indicated in Table 1.

3.5. Data Collection and Analysis

Primary data collection was done through the use of questionnaires, Interview

![]()

Table 1. Sample size for the study in Dadaab refugee camp.

Source: Researcher Data 2019.

guide, Focus group discussions and Observations checklist. Secondary data sources included books, research articles, website searches, records from Dadaab camp and other relevant literature. Quantitative data was coded and keyed into the Statistical Package for Social Scientists version (SPSS 22). Quantitative analysis was statistically used to describe, aggregates, and present the constructs that is, independent variable and dependent variable of the study. Analysis was done based on descriptive statistics and inferential statistics. Under descriptive statistics, frequencies and percentages were used to describe the data sets and results were presented in tables, graphs and charts while, qualitative data was coded and analysed in thematic narratives and in reported verbatim quotation.

4. Study Findings and Discussion

4.1. Demographic Information on Refugee Household Heads in Daadab Refugee Camp

The demographic information of refugee household heads was done through use of questionnaires. A total of 384 questionnaires were administered to the respondents and the response was actualized through follow ups. The demographic information collected through the questionnaires was classified into seven categories; country of origin, age of the household head, gender of household head, marital status, religion, education level and period of stay in the camp.

4.1.1. Country of Origin of Household Heads in Dadaab Camp

The study sought to establish the country of origin of 384 Household Heads. The respondents The Results in Table 2 indicate that, majority of respondents came from Somalia 254 (73.8%), followed by Ethiopia 41 (11.9%), South Sudan 36 (10.5%), Burundi 4 (1.2%), Congo 4 (1.2%) and Uganda 4 (1.2%) and Rwanda 1 (0.3%) respectively. The respondents’ Country of origin was significant, as it underscored the most conflict-troubled country that caused highest displacement and eventual migrations of its populations to the host Country. The displacement of refugees into the host country could be attributable to various causes, which include but are not limited to violence, poverty, conflict, persecution and perpetual

![]()

Table 2. Distribution of respondents’ as per their country of origin in Dadaab camp.

Source: Field Data, 2019.

killing of citizens by the government in the country of origin. Refugees in Dadaab Camp live in constant fear of attacks and insecurity especially from Somalia as there is still influx of the displaced into the camp. Sharma et al. (2020) assert that, Somalia has one of the highest rates of child marriage, with 45% of women aged 20 - 24 married before the age of 18, and 8% married before 15 years of age. As such the highest number of entrants came from troubled countries such as Somalia. Refugees are the weakest and most vulnerable category in a conflict-setting (El-Khatib et al., 2013). Violence against lesbians, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) in conflict settings has been recognized by the United Nations as a form of gender based violence that is often motivated by homophobic and transphobic attitudes and directed at those perceived as defying hegemonic gender norm (Kiss et al., 2020). In conflict settings, lesbians, gay, bisexual and transgender people often experience harassment and need to hide their sexual orientation or gender identity (Kiss et al., 2020).

Study demonstrate that, Somalia, Ethiopia and South Sudan had the highest number of refugees’ entrants into the camp, while Burundi, Congo, Uganda and Rwanda had the lowest number of refugees’ entrants into the Camp as shown on Table 2.

4.1.2. Age of Household Heads of Refugees in Dadaab Camp

The study sought to find out the Age of Household heads 384 refugees in Dadaab Camp. Table 3 shows that, majority 115 (33.5%) of house hold heads were between 35 - 55 years of age, followed by 112 (32.7%) of respondents were between 22 - 35 years of age, which was closely followed by 56 (16.3%) of house hold head which were between 16 - 21 years of age, and 54 (15.7%) of house heads were between 55 - 75 age. Lastly, 6 (1.7%) of the house hold heads were 75 years and above of age. Most of the house hold heads in Dadaab camp seem to range between 16 - 55 years of age as illustrated in Table 3.

The highest number of house hold heads that participated in the study was 33.5% and ranged between 35 - 55 of age, followed closely by 32.7% ranging at 22 - 35 of age, 16.3% that ranged between 16 - 21 of age, 15.7% that ranged between 55 - 75 of age and lastly, 1.7% that ranged between 75 and above of age. This underscored the age of house hold heads in the camp. Moreover, the age of household heads in this study ranged between 16 - 75 years. As such, majority of house hold heads that participated in this had wider exposure to traumatic experiences, given their age, either in the camp, during migration or in the country of origin.

4.1.3. Gender of Household Heads of Refugees in Dadaab Camp

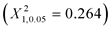

The study sought to determine the gender of Household heads of 384 refugees in Dadaab Camp. Study results indicated in Figure 2 therefore illustrate that, out of 337 respondents, the study found out that, majority (181; 53.7%) of gender of household heads were male while only (157; 46.3%) of gender of household heads were female. The gender of Household heads in this study was significant, as it demonstrated the gender of household heads that participated in the study which further demystified their extent of exposure to conflict and post conflict stressors. The Chi-Square value  depicts a significant difference in the gender of the household heads among refugees as P-value of 0.0233. In this study, majority of household heads who participated in the study were male compared to female house hold heads as shown in Figure 2.

depicts a significant difference in the gender of the household heads among refugees as P-value of 0.0233. In this study, majority of household heads who participated in the study were male compared to female house hold heads as shown in Figure 2.

Study demonstrated that 53.7% of male respondents participated in the study

![]()

Table 3. Distribution of age of household heads in Dadaab camp.

Source: Field Data 2019.

![]() Source: Field Data, 2019.

Source: Field Data, 2019.

Figure 2. Distribution of gender of household heads in Dadaab refugee camp, Kenya.

and only 46.3% of female respondents participated in the study respectively. Male respondents were the highest in gender of household heads than female gender of household heads in Dadaab camp.

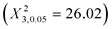

4.1.4. Marital Status of Respondents

The study sought to find out the marital status of the household of respondents in Dadaab camp. Study results show that, majority (n = 148; 43.7%) of the refugee respondents were in a marriage relationships (n = 133; 39.2%) of the refugee respondents were single (n = 34; 10.0%) of the refugee respondents had divorced or separated from their intimate partners and only (n = 24; 7.1%) of the refugee respondents were widowed. The Chi-Square value  on the variation of the marital status of the household head respondents was significant at P-Value 0.0310 in relation to the factors that triggered their migration to the Camp. The difference in marital status of the study respondents was significantly different in this study as it demonstrated that, 43.7% were in marriage relationship while, cumulatively 56.8% of the respondents were either single, divorced/separated or widowed as shown in Figure 3. Such significant difference in marital status of study respondents demonstrates that the study results were significantly affected by the respondents’ marital status.

on the variation of the marital status of the household head respondents was significant at P-Value 0.0310 in relation to the factors that triggered their migration to the Camp. The difference in marital status of the study respondents was significantly different in this study as it demonstrated that, 43.7% were in marriage relationship while, cumulatively 56.8% of the respondents were either single, divorced/separated or widowed as shown in Figure 3. Such significant difference in marital status of study respondents demonstrates that the study results were significantly affected by the respondents’ marital status.

Study results illustrate that majority of respondents in this study were in marriage relationship. Globally it is estimated that at least one out of every three women experiences violence or abuse at the hands of an intimate partner or non-partner throughout their life time. Women and girls are at even higher risk of violence in conflict and humanitarian crises due to a number of factors, including displacement, the breakdown of social structures, a lack of law enforcement, the potential further entrenchment of harmful gender norms, and the loss of livelihood opportunities for both men and women in the community among others.

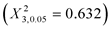

4.1.5. Religious Affiliation of Respondents

The study sought to find out the religious affiliation of the house hold heads. It was determined by use of four constructs: Islam, Christian, traditionalist and others. Figure 4 show, Majority (n = 256; 76.9%) of the respondents were Muslim,

![]() Source: Field Data, 2019.

Source: Field Data, 2019.

Figure 3. Marital status of respondents.

![]() Source: Field Data, 2019.

Source: Field Data, 2019.

Figure 4. Religious affiliation of house hold heads at Dadaab camp.

(n = 67; 20.1%) of the refugee respondents were Christians, (n = 9; 2.7%) of the refugee respondents were Traditionalist and only (n = 1; 0.3%) of the house hold heads had other religious affiliation. From the Chi-Square value  of the variation in the religious affiliation of the household head respondents was not significant at a P-value 0.0603 with regard to the nature of the traumatic experience of the refugees in the camp. However, although majority of the refugee respondents were affiliated to Islam as a religion, closely followed by Christianity, religious affiliation seems not to have connection with the nature and extent of traumatic experiences among refugee respondents.

of the variation in the religious affiliation of the household head respondents was not significant at a P-value 0.0603 with regard to the nature of the traumatic experience of the refugees in the camp. However, although majority of the refugee respondents were affiliated to Islam as a religion, closely followed by Christianity, religious affiliation seems not to have connection with the nature and extent of traumatic experiences among refugee respondents.

Religion has a comprehensive role in the life of Somalis and a belief system, culture and a way of life. Islamic religion for most Somali refugees had influence in their life and interaction with other refugees who were not affiliated to Islamic religion. The role of Islam has been crucial in providing a partial and temporary “horizontal identity” which has helped rival clans overcome their hostility. Figure 4 illustrates the religious affiliation of the Household heads in Dadaab Camp.

4.1.6. Education Level of the Household Heads at Dadaab Camp

Study sought to find out the Educational level of the house hold heads. Study results illustrate that, majority (n = 117; 34.5%) of the house hold heads had attained Secondary school certificates (n = 61; 18%) of the respondents had no education (n = 44; 13.0%) of the respondents had completed primary school education (n = 31; 9.1%) of the respondents were primary school dropout, 28 (8.3%) of the respondents were Secondary school dropout, (n = 20; 5.9%) of the respondents had non-formal education, while (n = 20; 5.3%) of the respondents had attained undergraduate and only (n = 18; 5.3%) of the respondents had attained tertiary education. The Chi-Square value  on the variation of the level of education of the household heads was significant at a P-value 0.002 with regard to the nature and extent of the traumatic experience of the refugees in the camp. Table 4 illustrates the level of Education of the study respondents.

on the variation of the level of education of the household heads was significant at a P-value 0.002 with regard to the nature and extent of the traumatic experience of the refugees in the camp. Table 4 illustrates the level of Education of the study respondents.

Study findings reveal that, 5.3% of the respondents had attained tertiary education and 5.9% of the respondents had attained University education level. However,

![]()

Table 4. Educational level of the respondents.

Source: Field, Data 2019.

cumulatively, 88.8% of the respondents had attained Secondary school education and below, while others had no formal education. The fact that majority of the respondents had attained secondary education and below reflects that most of the respondents of the house hold heads had challenges to understand what study sought to establish. The level of Education of the respondents was crucial as it demonstrated the respondents’ understanding of the nature and extent of traumatic experiences among refugees in Dadaab camp, Kenya.

4.1.7. Period of Stay in the Camp

The study sought to establish the period of stay of the house hold heads of respondents in the camp. Study results in Figure 5 illustrate that, majority (n = 109; 33.4%) of the respondents had been in the camp for 10 - 20 years, (n = 107; 32.8%) of the respondents had been in the camp for more than 20 years, (n = 73; 22.4%) of the respondents had been in the camp for 5 - 10 years, (n = 34; 10.4%) of respondents had been in the camp for 1 - 5 years and only (n = 3; 0.9%) of the respondents had been in camp for less than a year. Overall, most household heads in this study demonstrate that they had been in the camp for one year and above, and only 3 household heads had been in the camp for less than a year. The period of stay in the camp was significant in this study, as the period of stay in the camp reflected the experiences acquired as a result of conflict and protracted post-conflict situation in the camp. The results on period of stay of household heads are displayed in Figure 5.

In relation to the inferential statistics, the Chi-Square value  variation in period of stay of the respondents was significant at a P-value 0.001 with regard to the extent of traumatic experiences of the household heads in the camp. The period of stay in camp was significant in this study, as this reflected the embedded traumatic experiences and mental health conditions of the respondents. The situation of refugee camp in Dadaab is akin to the environment in urban slums of Africa which are characterized by insecurity and lack of basic amenities. Factors such as poor quality of living within the refugee camp, experiences of racism in the host country, joblessness, administration difficulties in the camp and, insecurity in refugees’ status and the longer stay in the host country contribute to the maintenance of mental health disorders and may be responsible for differences between countries (Mahmood et al., 2019).

variation in period of stay of the respondents was significant at a P-value 0.001 with regard to the extent of traumatic experiences of the household heads in the camp. The period of stay in camp was significant in this study, as this reflected the embedded traumatic experiences and mental health conditions of the respondents. The situation of refugee camp in Dadaab is akin to the environment in urban slums of Africa which are characterized by insecurity and lack of basic amenities. Factors such as poor quality of living within the refugee camp, experiences of racism in the host country, joblessness, administration difficulties in the camp and, insecurity in refugees’ status and the longer stay in the host country contribute to the maintenance of mental health disorders and may be responsible for differences between countries (Mahmood et al., 2019).

4.2. Respondents Experiences of War, Political Violence, Loss of Family Members, Persecution, Torture, Conflict, Displacement and Imprisonment in the Country of Origin or Dadaab Camp

The respondents were asked whether they had experienced war, conflict, displacement, persecution, torture, imprisonment and loss of family members in their country of origin, during migration and post-migration. Study findings demonstrate that, majority (n = 291; 87.9%) of the respondents admitted that they had experienced war, political violence, loss of family members, persecution, torture, conflict displacement and imprisonment, while only (n = 40; 12.1%) of the respondents had not experienced war, conflict, persecution and displacement in the country of origin or Dadaab camp as reflected in Figure 6.

The study results demonstrate the extent to which the respondents were

![]() Source: Field Data, 2019.

Source: Field Data, 2019.

Figure 5. Period of stay of house hold head in Dadaab camp.

![]() Source: Field Data, 2019.

Source: Field Data, 2019.

Figure 6. Results on respondents’ experience of war, conflict, political violence, displacement, torture, persecution and loss of family members.

exposed to traumatic experiences in their country of origin as well as in Dadaab camp.

4.3. Ways in Which These Traumatic Experiences Have Manifested

The refugees were asked ways in which these traumatic experiences have maifested, Study found out that, out of 400 refugees who participated in the study, majority (n = 235; 85.1%) of respondents admitted having manifested with generalized fear, (n = 32; 11.6%) of the respondents disagreed having manifested with Generalized fear and only (n = 9; 3.3%) of the respondents did not know that generalized fear was a manifestations of traumatic experiences.

On whether nightmare was a manifestation of traumatic experience among refugees, Study found out that out of 400 refugees who participated in the study, majority (n = 166; 67.2%) of the respondents agreed that they manifested with nightmares due to exposure to traumatic experiences, (n = 68; 27.5%) of the respondents disagreed having manifestations of nightmares due to exposure to traumatic experiences and (n = 13; 5.3%) of the respondents did not know that nightmare was a manifestation of traumatic experiences.

On whether manifestations of specific phobia stimuli was a manifestation of traumatic experience, study results show that out of 400 refugees who participated in the study, majority (n = 168; 69.4%) of the respondents manifested with specific phobias stimuli while, (n = 48; 19.8%) of the respondents disagreed having specific phobia manifestations and only (n = 26; 10.7%) of the respondents did not know that specific phobia stimuli was a manifestation of traumatic experience.

On whether anxiety was a manifestation of traumatic experience, study found out that out of 400 refugees who participated in the study, majority (n = 167; 69.6%) of the respondents manifested with anxiety while, (n = 46; 19.2%) of the respondents disagreed having any manifestations of anxiety and only (n = 27; 11.3%) of the respondents did not know that anxiety was a manifestation of traumatic experience.

On whether suspiciousness was a manifestation of traumatic experience, study found out that, majority (n = 156; 68.4%) of the respondents manifested with suspiciousness while (n = 42; 18.4%) of the respondents disagreed having manifested with suspiciousness due to traumatic experiences and only (n = 30; 13.2%) of the respondents did not know that suspiciousness was a manifestation of traumatic experiences due to exposure to traumatic experiences.

As to whether depression was a manifestation of refugees traumatic experience, study results demonstrate that out of 400 refugees who participated in the study, majority (n = 225; 85.2%) of the respondents manifested with depression while, (n = 26; 9.8%) of the respondents disagreed that depression was a manifestations of traumatic experience and only (n = 13; 4.9%) of the respondents did not know that depression was a manifestation of traumatic experiences.

As to whether sadness was a manifestation of traumatic experience, study results show that out of 400 respondents who participated in the study, majority (n = 227; 88.7%) of the respondents agreed that sadness was a manifestation of traumatic experience, while (n = 19; 7.4%) of the respondents disagreed that sadness was a manifestation of traumatic experience and only (n = 10; 3.9%) of the respondents did not know that sadness was a manifestation of traumatic experience.

As to whether insomnia/lack of sleep was a traumatic experience manifested by refugees, Out of 400 refugees who participated in the study, majority (n = 163; 67.4%) of the respondents agreed that insomnia/lack of sleep was a manifestation of traumatic experience, (n = 63; 26.0%) of the respondents disagreed that insomnia/lack of sleep was a manifestation of traumatic experience and only (n = 16; 6.6%) of the respondents did not know that insomnia/lack of sleep was a manifestation of traumatic experience.

Study found out that, out of 400 refugees who participated in the study, majority (n = 143; 59.1%) of the respondents agreed that easily irritable and isolation was a manifestation of traumatic experience (n = 74; 30.6%) of the respondents disagreed that easily irritable and isolation was a manifestation of traumatic experience and (n = 25; 10.3%) of the respondents did not know that easily irritable and isolation was a manifestation of traumatic experiences.

The results indicate a statistically significant association between general traumatic manifestation and experiences of war, political violence among others with P-value of 0.00. The specific psychological distress that showed a statistically significant association was Depression (p = 0.00), nightmares (p = 0.02), phobias (p = 0.00), sadness (p = 0.00), easily irritable (0.006), suspicion (p = 0.033). However, drug and substance abuse, anxiety and insomnia showed statistically insignificant link to the experiences of war, violence and torture among refuges with drug and substance abuse (p = 0.86) anxiety (0.102) insomnia (P = 0.059) as shown on Table 5 respectively.

The camp itself exacerbated mental health conditions as refugees were exposed to poor living conditions, poor accommodations, lack of mental health care, outbreak of communicable diseases and insecurity as this was in consistent with Hassan et al. (2016) when they assert that, emotional manifestations include sadness, fear, grief, frustration, anxiety, anger and despair. While the United Nation High Commissioner for Refugees and other Non-governmental organizations have services to address refugees’ mental health, these resources were lacking (Mjur, 2017). According to across studies, prevalence rates of PTSD and other mental health problems among war-affected populations vary widely (Mahmood et al., 2019).

4.4. Whether These Traumatic Experiences Manifested Periodically in the Camp

The refugees were asked whether these traumatic experiences manifested periodically in the camp, Nonetheless. majority (n = 119; 47.0%) of respondents had manifestation of traumatic experiences once daily, (n = 134; 53.0%) of the respondents had manifestation of traumatic experiences more than once daily, (n = 83; 38.6%) of the respondents had manifestation of traumatic experiences once weekly, 132 (61.4%) of the respondents had manifestation of traumatic experiences more than once weekly, (n = 60; 22.2%) of the respondents had manifestation of traumatic experiences once monthly, while (n = 210; 77.8%) of the respondents had manifestation of traumatic experiences more than once monthly as reflected in Table 6.

Study results demonstrate that, out of 400 refugees who participated in the study, 53% of the respondents had manifestation of traumatic experiences more than once daily, while 47% of the respondents had manifestation of traumatic experiences, just once daily. Consequently, results on the weekly manifestation of traumatic experiences shows that, 38.6% of the respondents had manifestation of traumatic experiences once weekly, while 61.4% of the respondents had manifestation of traumatic experiences more than once weekly. Finally, only 22.2% of the respondents had manifestation of traumatic experiences once monthly and only 77.8% of the respondents had manifestation of traumatic experience more than once monthly. Overall, there was a significant manifestation of traumatic experiences among refugees on the daily, weekly and monthly basis. Arguably, according to Stromme et al. (2020), forcibly displaced individuals

![]()

Table 5. Ways in which traumatic experiences have manifested at Dadaab camp, Kenya

Source: Field data, 2019.

![]()

Table 6. Manifestation of traumatic experiences periodically among refugees while in Dadaab camp, Kenya.

Source: Field data, 2019.

frequently experience profound psychological distress, which may manifest as mental disorders but also as somatic complaints such as pain. However, many of those who experience conflict-driven, often highly-traumatic forced migration do not develop mental disorders despite being at risk (Siriwardhana & Wickramage, 2014). This could be attributable to various factors which buffer mental health conditions amongst refugees despite the exposure. What has been noted to cause the difference is that, Factors such as individual and/ or community resilience and social support have been highlighted as key potential mediators of between forced migration experience and subsequent mental health impact (Siriwardhana & Wickramage, 2014).

4.5. The Time of the Day When Traumatic Flashbacks Are More Common among Refugee in Dadaab Camp

The refugees were asked the time of the day when traumatic flashbacks are more common. Study results show that, out of 400 refugees who participated in the study, majority (n = 170; 58.8%) of the respondents experienced traumatic flashbacks during the night while (n = 76; 26.3%) of the respondents experienced traumatic flashbacks during the day, and (n = 43; 14.9%) of the respondents admitted that they experienced traumatic flashbacks during the day and night as reflected in Figure 7.

The study results were in consistent with Serpeloni et al. (2021), when they averred that, intrusion nightmares or flashbacks occur with a sense of trauma happening again here and now. The psychotic features do not exclusively occur in relations to flashbacks, and that they are chronic (Nygaard et al., 2017). Further, the symptoms described primarily consist of hallucinations and delusions, and are generally related to the refugees’ trauma (Nygaard et al., 2017). Alarm responses can become activated by even small and subtle prompts (Serpeloni et al., 2021). This results into re-experiencing which occurs without the awareness of the past and present (Serpeloni et al., 2021). In the literature, a diagnostic entity called complex PTSD has long been discussed, as survivors of prolonged and

![]() Source: Field Data, 2019.

Source: Field Data, 2019.

Figure 7. Time of the day when traumatic flashback were more common among refugees in Dadaab camp.

repeated trauma often report additional symptoms alongside their PTSD (Nygaard et al., 2017). The symptoms reported in the literature are, for example emotional regulation difficulties, dissociative and psychotic symptoms and somatic distress (Nygaard et al., 2017). Symptoms of post-traumatic stress are the results of intrinsic mnesic dynamics induced by the inherent properties of storing and retrieving information gathered during multiple traumatic events (Serpeloni et al., 2021). Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) with secondary psychotic features (PTSD-SP) has similarly been discussed as a separate diagnostic entity in which PTSD is followed by the appearance of psychotic features (Nygaard et al., 2017). Overall, most refugees commonly experienced traumatic flashbacks during the night.

5. Conclusion

This study concludes that evidently, majority 87.9% of refugees in Dadaab camp had experienced war, conflict and political violence, while just a few 12.1% of refugees in Dadaab camp had not experienced conflict and violence. The effect of these traumatic experiences resulted in depression, generalized fear, insomnia and anxiety among refugees. Consequently, there were periodic manifestations of traumatic experiences, which erratically led to mental health disturbance.

6. Recommendations

This study recommends that, since mental health conditions are very debilitating, and especially to refugees affected by conflict, UNHCR in collaboration with the host government should scale-up human resource capacity by training more Aid workers on culturally responsive psychosocial interventions which can enhance social and mental health of refugees. Additionally, More Specialized professionals on mental health and psychosocial support should be deployed in the camp to supervise the overall provision of social and mental healthcare to the refugees.

Acknowledgements

The researchers specifically thank the Supervisors; Prof. Peter Odera and Dr. Ruth Simiyu for their constructive critique. I thank the respondents for the valuable information that made this study a reality.