Development of a Reproducible Rating System for Sun Protective Clothing That Incorporates Body Surface Coverage ()

1. Introduction

Ultraviolet radiation (UVR) is a known carcinogen. Skin cancer is the most common form of cancer in humans, and typically affects sun-exposed parts of the body. Australasia experiences extremely high levels of ambient UVR year-round [1]. Consequently, Australasia boasts the highest rates of melanoma (the most dangerous form of skin cancer) and epithelial skin cancer globally [2]. Two-thirds of Australians are diagnosed with skin cancer by age 70 years [3], and the cost of epithelial skin cancer alone exceeds $512.3 million per .a. in Australia [4].

1.1. Risk Factors for Skin Cancer

The number of common, benign pigmented moles a person develops is the strongest marker of melanoma risk [5], with the presence of multiple moles increasing the risk of melanoma 20-fold [6]. This association has been verified in numerous case-control studies [5]. Only one percent of babies are born with a pigmented mole, yet many people develop tens to hundreds of them by adulthood [5], with the highest densities occurring on sun-exposed body-sites [7].

Excessive mole development is related to childhood sun exposure [8]. Caucasian immigrants who arrive in Australia after 10 years of age develop fewer pigmented moles than the “native” Caucasian population and are less likely to develop melanoma [9] [10]. Likewise, children from tropical Australia develop pigmented moles earlier and in higher numbers than children from temperate regions in Australia or abroad, and are at greater risk of melanoma as a consequence [11] [12]. The association between sun exposure and mole development includes acute and chronic patterns of exposure, with a single sunburn before age 7 years almost doubling the risk of excessive mole development, and spending four or more hours outdoors each day more than tripling the risk [8].

1.2. Photo-Protection by Clothing

Sun-protective clothing, such as broad-brim hats and long-sleeved shirts provide a physical barrier that helps to protect the skin from UVR [13]. Swimsuits that cover the trunk and incorporate longer sleeves and pants are ideal for water-based activities since, unlike sunscreen, they do not require reapplication [14] [15]. Ecological evidence suggests that Australian children born since Nylon Elastane rash-vests and all-in-one sun-suits gained popularity, have fewer pigmented moles on their back than children born earlier [16]. More recently, the only randomized controlled trial to evaluate the efficacy of sun-protective clothing confirmed that wearing garments made from darker-colored, tightly woven fabrics covering a substantial proportion of the body slows the rate of mole development in Caucasian Australian children [17]. Thus, well designed sun-protective clothing can reduce melanoma risk in susceptible populations, particularly if worn regularly from early childhood [17].

1.3. Australian and New Zealand Standard for Sun-Protective Clothing

In July 1996, Australia was the first nation to introduce a standard for the evaluation and classification of clothing claiming a sun-protective advantage [18]. Known as AS/NZS 4399:1996, this joint Australian and New Zealand Standard introduced a reproducible measurement and classification protocol based on the relative ranking of the transmission of UVR through the fabric from which the garment is made [19]. This standard outlines all of the technical specifications related to measuring UVR transmittance as well as describing the Ultraviolet Protection Factor (UPF) labeling specifications that manufacturers, wholesalers and retailers wishing to classify garments according to the UPF classification scheme are expected to adhere to [19].

The UPF-labelling of sun-protective garments was devised with the intention of enabling consumers to make informed clothing purchases. The standard and its associated UPF rating system is still widely used today, almost 20 years since it was introduced [18]. Fabrics that achieve UPF ratings of 40, 45, 50 or 50+ block at least 97.5% of erythemally effective (EE) UVR (i.e. those wavelengths in the ultraviolet spectrum responsible for causing the sunburn response in human skin). In simple terms, a UPF 50 fabric allows only 1/50th of the UVR to reach the skin [18]. Fabrics with UPF ratings of 40 and above are considered to provide “excellent” sun-protec- tion, and can be labelled as such, while fabrics in the “very good” category have UPF ratings of 25 - 35 and block 96% - 97.5% of EE-UVR [20]. Similarly, fabric bolts and apparel rated as UPF 15 - 20 block 93.3% - 95.9% of EE-UVR and can display the words “good sun-protection” on their swing tags [18]-[20].

AS/NZ 4399:1996 and its associated UPF rating system have been adopted almost universally by the textile industry. However, it only evaluates the transmission of EE-UVR through fabric, without taking into consideration the proportion of the body surface coverage afforded by the design of the garment [13]. While ever AS/NZS 4399:1996 does not specify a minimum body surface proportion that must be covered by a garment in order to claim a sun-protective advantage it will be vulnerable to exploitation. For instance, a sun-protective advantage could be claimed for brief or scant items of apparel, such as bikini swimwear, because they are made of fabrics such as Nylon Elastane (e.g. LYCRA®) that often achieves a 50+ UPF rating [14]. Under a standard where UPF is the only determinant used to assess the sun-protective benefit of clothing [19], brief swimwear typically achieves the technical specifications of the “excellent” sun-protection category [13]. Thus, currently AS/NZS 4399:1996 provides an avenue whereby manufacturers of brief swimwear and apparel could feasibly make misleading claims of a sun-protective advantage. This loop-hole needs to be closed [13].

In light of recent evidence that garments that cover a greater proportion of the body’s surface area (BSA) help to protect children from developing numerous pigmented moles [17], plans to develop a rating system that evaluates both the BSA and UPF of sun-protective garments seems warranted [13] [17]. Standards Australia and Standards New Zealand Technical Committee TX-021 for the Evaluation and Classification of Sun Protective Clothing recently convened to revise AS/NZ 4399:1996 to address the potential vulnerabilities that have come to light during the 19 years this ground-breaking Standard has been in use [21]. Public comments on proposed revisions to the Standard are invited from industry to ensure it will represents the views of all stakeholders [21].

Here, we discuss our research into and progress towards developing an evaluation protocol devised with the specific intention of quantifying the BSA coverage of sun-protective garments.

2. Rationale for Mannequin Selection

We decided to begin by developing a protocol for quantifying the BSA coverage of children’s sun-protective clothing in the first instance due to the urgency suggested by research demonstrating the relevance of clothing cover in the body-site specific development of numerous pigmented moles (a major risk factor for melanoma development) on young Caucasian children from susceptible populations living in UVR-intense climates [17]. The height of available mannequins spanning ages 6 months to 12 years of age was investigated. Mannequins whose dimensions most closely matched the median length at ages 6-, 12- and 24-months [22] were selected for use in the development of this body surface model. Similarly, median heights were determined for children aged 4, 6, 8, 10 and 12 years from Height for Age Percentile charts for 2-18 year-olds [23] and compared to the dimensions of mannequins for this age range so the closest match could be determined. The range of child mannequins most suited to our needs was the Bendy Kids range of flexible standing mannequins. These mannequins offer an infinite number of adjustable poses and a felt covered surface that is easy to draw on.

3. Laboratory Methods

In order to make progress towards developing a reproducible evaluation and classification scheme for sun- protective clothing that takes into account both the UPF of the fabric (the technical specifications of which are already aptly described in AS/NZS 4399:1996) and the BSA coverage of the garment, it is first necessary to develop the latter to complete the puzzle. In this research, BSA is determined by comparing images of clothed and unclothed mannequins.

3.1. Marking Mannequins

The felt covered surface of a flexible mannequin was securely fastened to a typical optical bench in our Physics laboratory using a clamp around the neck and the left ankle, such that it was lying parallel to the bench. The mannequin was marked with horizontal bands drawn with a red indelible marker at 1 cm intervals with the aid of a Bosch laser level on a custom tripod. After the mannequin was marked up into cross-sections in this way from the top of the neck, through the torso and the full length of the right arm and the right lower limb, it was returned to the upright position, supported by its stand. This process was then repeated for mannequins of all sizes.

3.2. Photography Protocol

The first mannequin was placed on top of a table, against a wall covered with a neutral (black) non-reflective background. This was achieved using a backdrop of black felt. Photography lamps were positioned to prevent shadows from obstructing the view of the red lines marked on the mannequin as it was imperative that the lines be clearly visible in the digital images. An 8.0 Megapixel Canon digital SLR camera, fitted with an 18 to 55 mm zoom lens at f4.5 and supported by a tripod, was positioned a fixed distance from the mannequin and orientated with respect to a reference point, marked on the trunk of the mannequin and collinear with the camera’s optical axis. The mannequin image was framed from head to toe using the zoom function of the fitted camera lens to ensure the highest possible image resolution of the marks on the mannequin’s surface. A photograph of the unclothed mannequin was taken using the camera’s inbuilt fill-in flash. The image of the unclothed mannequin is shown in Figure 1 (at left). The same mannequin was then clothed in an upper body garment of the matching size and re-photographed (see Figure 2, at left). This process was repeated for mannequins of all sizes.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Figure 1. Creating a body surface template for the upper body. The marked mannequin is photographed (left). The mannequin surface is framed by removal of the background image (center). Image processing of the marked body surface is used to count line segments and highlight them in a false image color (right).

![]()

![]()

![]()

Figure 2. Measuring covered BSA is a 3 step process. The marked mannequin is fitted with a garment and photographed (left). The mannequin surface is framed by removal of the background image (center). Image processing of the marked line segments is used to show the surface of the body not covered by the garment (right).

4. Methodology for Determining the Body Surface Area Covered by Clothing

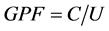

By comparing the red lines marked on the mannequin body surface we were able to determine the BSA covered by the garment being evaluated. The relative BSA covered by a garment made from UPF ratable fabric (UPF of at least 15), and thereby, the extent of protection the garment offers can be expressed as the ratio of the number of lines visible on the clothed mannequin to the number of lines visible on the same unclothed mannequin. This is expressed by the ratio,

(1)

(1)

where:

GPF is the Garment Protection Factor; C = the number of lines visible on the clothed mannequin; U = the number of lines visible on the unclothed mannequin. For a line to be counted as “visible” the entire line segment must be discernable and not be obscured by clothing in any way. In this manner, the total BSA coverage of a garment can be assessed as a long-sleeved shirt covers a greater number of total line segments than a short- sleeved shirt.

4.1. Calculating the Garment Protection Factor for Upper and Lower Body Garments

In the interest of being able to develop a rating system to inform consumers about the relative BSA covered by separate garments, it is necessary to be able to calculate GPF for both upper and lower body garments. For consistency with the newest iteration of the Standard, the definitions of the upper and the lower body regions used in this protocol match those used in the draft revision DR AS/NZ 4399:2015 [21]. The upper body is defined as including the anterior, posterior and lateral aspects of the torso extending upwards from the hip line to the base of the neck and across the shoulders and down the arms to the wrist. Upper body garments include items such as rash-vests, polo shirts, button-up shirts, and t-shirts. As it would be misleading to permit brief garments to claim a sun-protective advantage [13], in the proposed rating system, a claim of sun-protective advantage will be indicated by superior GPF and UPF values, and will only be granted to and displayed by upper body garments that fully cover the shoulders and from the neck down to the hip line, so that the posterior torso is fully covered. This definition allows for the anterior surface of the garment to open partially or fully (via buttons or a zipper etc.).

Consistent with the draft Standard, the lower body is defined as extending from the hip line, down the legs to the ankles, such that the area considered incorporates the buttocks, the pubic region, and the anterior, posterior and lateral aspects of the thighs and the lower legs [21]. Lower body garments include trousers, shorts, skorts, culottes, and skirts. Lower body GPF will not be displayed on garments such as swimwear that does not cover to at least the midway point of the crotch and the knees to prevent manufacturers and retailers from inappropriately claiming a sun-protective advantage for brief lower body garments [21].

All lines visible above the hip line and on the arms and neck of the mannequin clothed with an upper body garment are counted to determine GPF as described in Equation (1) above. While on a mannequin clothed with a lower body garment, all lines visible from the hip line down to the ankle are counted to determine GPF with the same equation. Further configurations will cater for all-in-one garments like Nylon Elastane sun-suits.

4.2. Using Image Processing Techniques to Calculate the Garment Protection Factor

To expedite the calculation of GPF for either upper body or lower body garments, an algorithm was developed using MATLAB software Release 2013b [24] to count the number of lines marked on the “unclothed” and “clothed” mannequin models. Digital images of the “clothed” and “unclothed” mannequins (taken in accordance with the photography protocol described in 3.2) were imported into MATLAB. The mannequin image was then framed relative to the background to outline the body surface area. This was achieved by removing all image pixels with a red, green and blue saturation of less than 0.75 on a scale of 0 to 1. Marked line segments on the mannequin model were isolated by comparison of the difference in red and green, and red and blue levels in each image pixel defined to be on the mannequin surface. In this way, the marked surface lines, (drawn on the mannequin in red) were classified by the algorithm for pixels which had more red than green, and also more red than blue.

The difference used to classify a marked line on the mannequin model is variable and can be accommodated for by the algorithm by enhancing image brightness and contrast. Line marks automatically classified by the algorithm were given a false color and counted by the algorithm for either the upper body or lower body sections (the upper and lower body sections are divided anatomically at the hip line as described in 4.1). An example of the algorithm is shown for an upper body garment in Figure 2.

5. Conclusion

We envisage that our research into and progress towards developing an evaluation protocol devised with the specific intention of quantifying the BSA coverage of garments will complement the existing UPF rating system for fabric. This work may influence international standards for sun-protective clothing in the future.

Acknowledgements

The authors received salary and travel support from James Cook University and the University of Southern Queensland to undertake this research. We thank Alex Rawlings for his assistance in marking the mannequins.