1. Introduction

The genus Fusarium is responsible for several plant health problems. One of them is in crop production of tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum), at global and national levels. A particular example is the fungus Fusarium oxysporum, which causes vascular wilt. Fusarium moniliforme is responsible for the rot from the cob and corn stalk, meanwhile, the corn consumption from infected plants, is a threat to the health of the animals and therefore the main cause of the production of carcinogenic toxins [1]. Other Fusarium species have been reported to cause problems in seeds of different varieties of beans, especially in the variety “Azufrado Tapatio” [2].

Fusarium solani is a necrotrophic parasitic fungus that produces wilting in potato plants, corn, lemon, tomato and other Solanaceae, causing economic losses very severe [2-5]. This pathogen can directly penetrate the plant tissue through wound and spread plant as chlamydoconidia or conidia, which occurs when infected crop residues are carried by water, wind or farm implements.

These damages are observed when there is compacted soil, excessive moisture in the soil and in the drought. The fungus can live indefinitely as a saprophytic organism in the organic matter in chlamydoconidia shaped, and it is not transmitted through the seed plants.

In the literature, there are very few reports of fungal cellulolytic enzymes of Fusarium. It has been reported that F. oxisporum produces a variety of lytic enzymes, which depolymerize all components of plant cell walls, such as cellulose, xylan, pectin, polygalacturonic acids and proteins (extensins); and they have been purified and biochemically characterized as several enzymes, one endopolygalacturonase majority (PG1), two exopolygalacturonase (PG2 and PG3), one endoxylanase (XYL1), one endopectate lyase (PL1) [6,7], seven polygalacturonases of Fusarium species of Pinus pinea [8], and the isolation of differentially expressed genes during interactions between tomato cells and a strain of F. oxysporum [9]. With respect to F. solani, studies have reported the isolation of a novel pectate lyase gene from the phytopathogenic fungus F. solani [10], a F. solani mutant recurring in cutinase activity and virulence [11], extracellular lipase by the phytopathogenic fungus F. solani FS1 [12], and a cellulose of F. solani [13]. Therefore, it is important to try to determine cellulolytic enzymes involved in the pathogenesis of F. solani. The present study is undertaken with following objective: analyze the induction of enzymes lytic by the fungus F. solani isolated from a culture of tomato.

2. Experimental

2.1. Biosorbent Used: Fusarium solani

We used the phytopathogenic fungus Fusarium solani, isolated from a culture of tomato, located in the municipality of Villa de Arista, San Luis Potosi, México. The fungal isolate was routinely maintained in Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) at 28˚C. For his propagation, were used 250 mL Erlenmeyer flasks containing 100 mL of Mathur modified medium (MgSO4∙7H2O, 2.5 g; KH2PO4, 2.72 g, L-glutamic acid, 5.28 g; distilled water up to 1 L), to final pH 5.5 [14]. The medium was supplemented with different carbon sources: sigmacell (1% w/v) polygalacturonic acid (2% w/v), xylan (2% w/v), and glucose (2% w/v) for the activities of cellulose, polygalacturonase, and xilanase respectively. The prepared flasks were inoculated with 1 × 106 spores/mL, and were incubated at 28˚C, with constant stirring (100 rpm).

2.2. Induction of Extracellular Lytic Enzymes

The Fungus was inoculated into 250 mL Erlenmeyer flasks containing 50 mL of Mathur medium modified, supplemented sigmacell type 101 (Sigma), polygalacturonic acid (Sigma), xylan (Sigma), or glucose (Sigma) as carbon source, and incubated at 28˚C, with constant stirring at 100 rpm, and at different times (3, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 and 15 days), the supernatant was harvested by filtration and the extracellular lytic activity, was determined by the method of Nelson modified by Somogy [15,16].

2.3. Assay of Cellulolytic Activity

Enzyme activity was measured by a chromogenic method using carboxymethylcellulose (CMC, medium viscosity, Sigma), polygalacturonase (Sigma), and Xylan (Sigma) as substrates, reaction mixtures containing 0.5% of CMC, Polygalacturonase, or Xylan, the enzyme fraction and 50 mM sodium acetate buffer, pH 5.0, in a final volume of 3.2 mL were incubated at 30˚C. After 30 min of incubation at 37˚C in a water bath, the reducing sugars (glucose, galacturonic acid, and xylose equivalents liberated) were estimated by Nelson’s modified Somogy’s method [15, 16]. The color was read at 500 nm using a Spectrum UVVis Spectrophotometer. Glucose, galacturonic acid, and xylose were used as the standard. One unit (U) of cellulose, polygalacturonase and/or xylanase activity was defined as the amount of enzyme required to liberate 1 nanogram of glucose, galacturonic acid and/or xylose/ minute/mg of protein under the assay conditions.

2.4. Stability of Extracellular Lytic Enzymes

Stability of extracellular lytic enzymes was also studied by pre-incubating the crude enzyme at pH values from 5.5 for 7 days, at temperature of 28˚C and 4˚C, with the residual activity determined under standard conditions.

2.5. Effect of Nitrogen Source and pH

The influence of different nitrogen sources (asparagin, urea, glutamine, ammonium sulphate, ammonium nitrate, and glutamic acid on activity of extracellular lytic enzymes was studied by adding them to the reaction solution to final concentrations of 0.53 % w/v). The effect of pH on enzyme activity was determined by measuring the activity at 28˚C using citrate–phosphate (0.05 M, pH 4.0 - 5.5), phosphate (0.05 M, pH 6.0 - 7.0) buffers for 60 min. The activity was assayed at temperature of 28˚C.

2.6. Effect of Temperature and Protein Concentration

The effect of temperature on enzyme activity was determined by performing the standard assay procedure for 60 min within a temperature range of 28˚C - 70˚C in citratephosphate buffer (0.05 M, pH 5.5), and the effect of protein concentration was determined using variable amounts of enzyme protein (extracellular) in a range from 0 to 110 mg of enzyme/assay.

2.7. Protein Assay

Protein concentration was estimated by the Lowry’s method (Lowry et al., 1951) using bovine serum albumin as standard. Each experiment was performed three times by triplicate.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Each experiment was carried out in three replicates. Means of variable and standard error of the medium, the test was carried out to detect any significant differences between the results of control and the treated samples.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Induction of Extracellular Lytic Enzymes

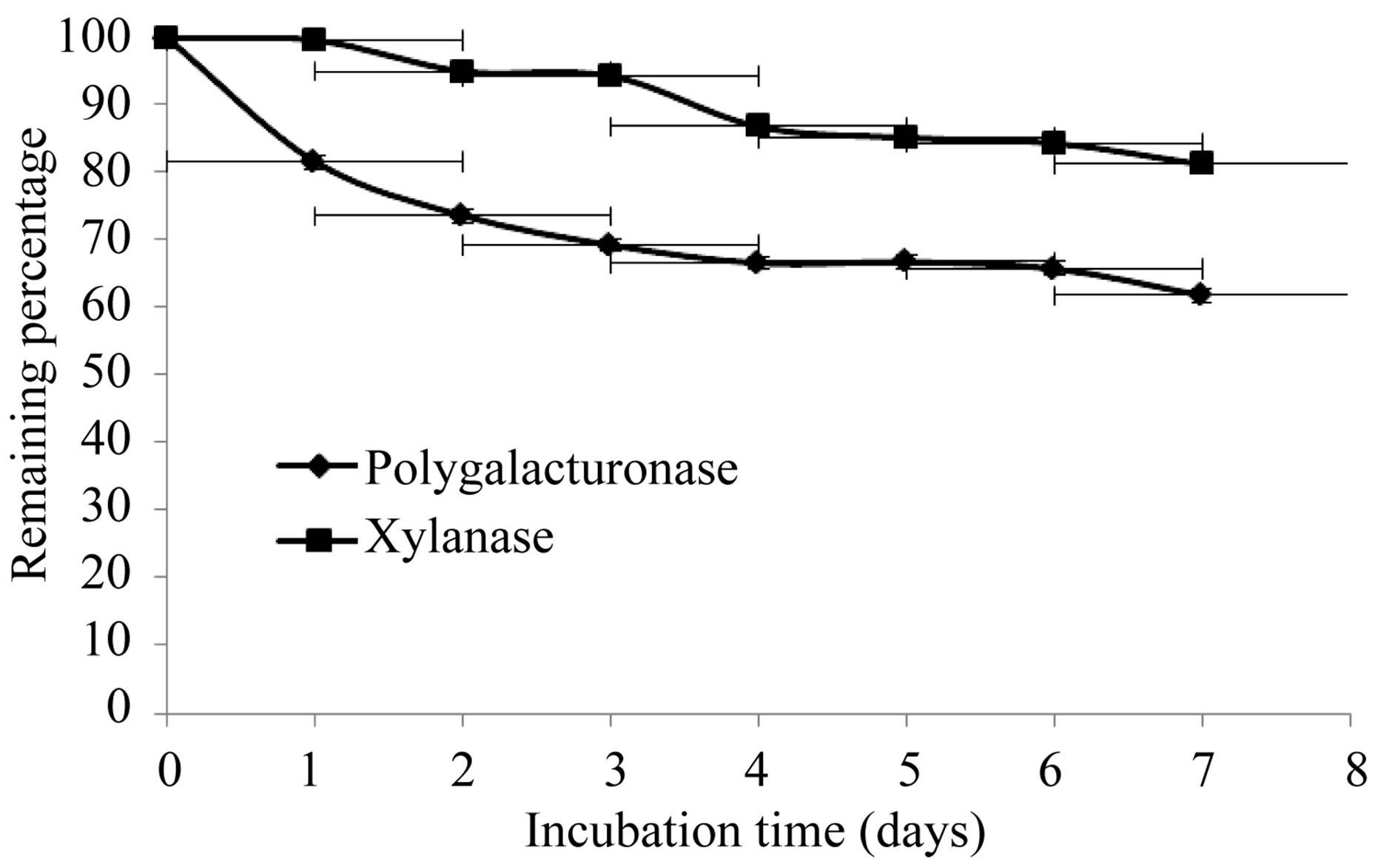

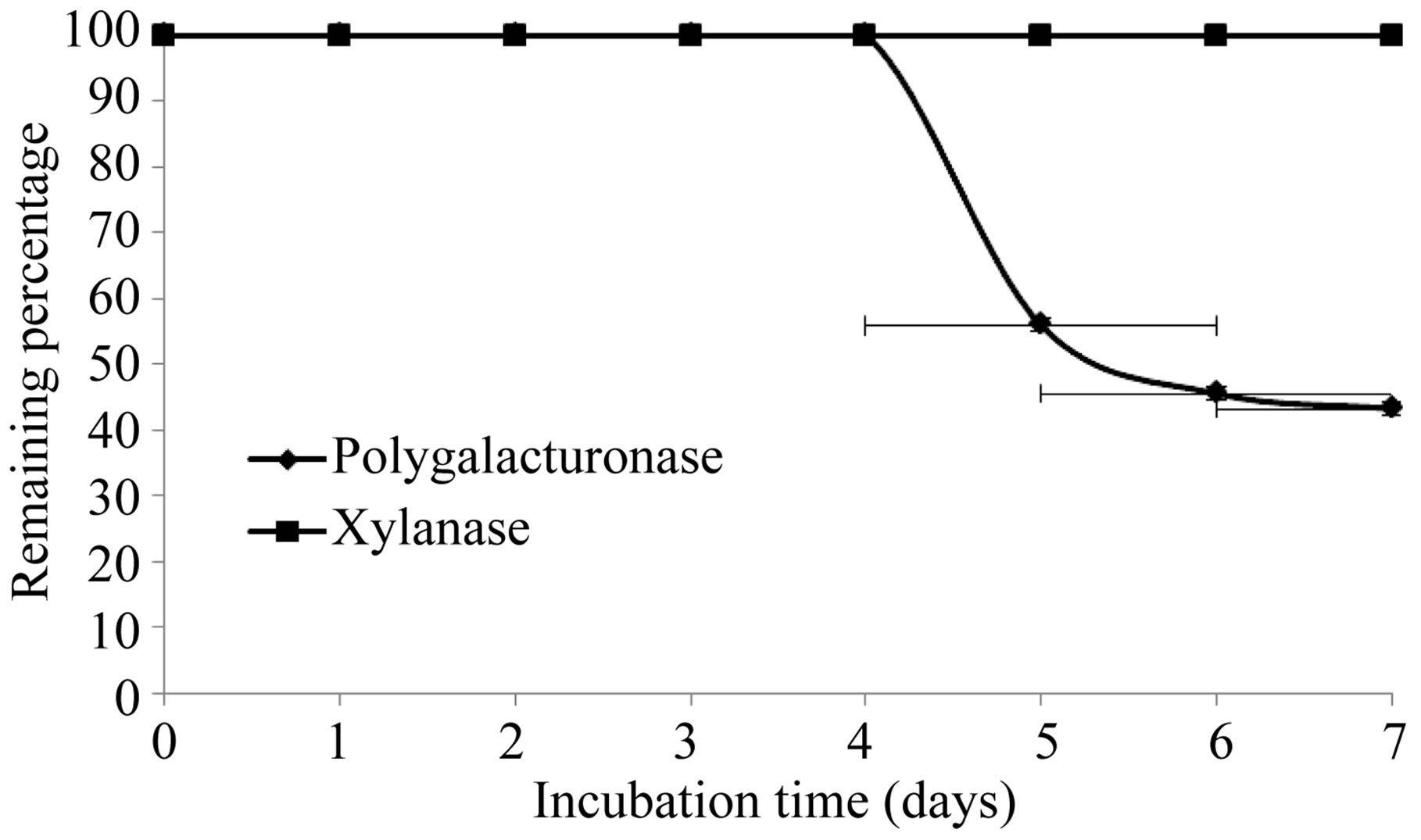

The production of extracellular lytic enzymes was induced, finding only polygalacturonase and xylanase activities, using polygalacturonic acid and xylan as sole carbon source. Also we not found any extracellular lytic activity when glucose was used as sole carbon source (Table 1). Activity for polygalacturonase reached a sharp peak after 10 days of incubation, while xylanase activity occurs at 13 days of incubation of the fungus at 28˚C (Figures 1 and 2) also xylanase activity, was very stable at 4˚C, after 7 days of incubation, has an activity of 100%, whereas the activity of polygalacturonase was of 43.8%. Stability at 28˚C was different for xylanase activity (81.2%), and for polygalacturonase was 61% (Figures 3 and 4).

For the induction of extracellular enzymes in Fusarium solani, there are few reports of this species in the literature, and there are referred to F. oxysporum or other species [6,7,18], but reports of F. solani were found as a pathogen associated celery in South America [19], infecting asparagus in five municipalities of Guanajuato [20], and vegetable and flower species in Jujuy, Argentina [21], and some different enzymes [10-13]. But not found any reports of F. solani in tomato, as the strain that was isolated from the culture of Villa de Arista, S.L.P.

Table 1. Induction of extracellular lytic enzymes by Fusarium solania.

a7 days of incubation. 28˚C. 100 rpm; bPolygalacturonase: nanograms of galacturonic acid/min/mg protein; Xylanase: nanograms of xylose/min/mg/ protein; Cellulase: nanograms of glucose/min/mg/protein; cN.D. Not Determined.

Figure 1. Induction of extracellular polygalacturonase activity by F. solani.

Figure 2. Induction of extracelullar xylanase activity by F. solani.

Figure 3. Stability of extracellular lytic enzymes of F. solani at 28˚C.

Figure 4. Stability of extracelular lytic enzymes of F. solani at 4˚C.

and used in this work.

Later, we induced extracellular cellulolytic activity at different times, in agitation an static cultures, without positive results up to an incubation period of 30 days for cultures in agitation and 60 days for static cultures (Tables 2 and 3), which is different from that reported by Wood [13], who report cellulolytic activity for a strain type of F. solani (I.M.I. 95994) using Avicell (microcrystalline cellulose) as substrate, at 7 days of incubation at 37˚C, and a reaction time of 18 hours, while in this work was to 28˚C and with a reaction time of 1 hour.

Table 2. Induction of extracellular cellulolytic enzymes by Fusarium solani at different timesa.

a28˚C. Static cultures; bCellulase: nanograms of glucose/min/mg/protein; Polygalacturonase: nanograms of galacturonic acid/min/µg protein; cCarboxymethyl cellulose: (0.5%, w/v) in buffer of acetates 50 mM, pH 5.0; dEthylcellulose: (1 mg/mL, w/v), in buffer of acetates 50 mM, pH 5.0; eSigmacell type 101 (1 mg/mL, w/v) in buffer of acetates 50 mM, pH 5.0.

Table 3. Induction of extracelular cellulolytic enzymes by Fusarium solani at different timesa.

a28˚C. Stirring cultures, with Sigmacell type 101 (cellulose) to 2.5% (p/v); bCellulase: nanograms of glucose/min/mg/protein; cCarboxymethyl cellulose: (0.5%, w/v) in buffer of acetates 50 mM, pH 5.0; dEthylcellulose: (1 mg/mL, w/v), in buffer of acetates 50 mM, pH 5.0; eSigmacell type 101 (1 mg/mL, w/v) in buffer of acetates 50 mM, pH 5.0; N. D. (Not Determined).

Too, has been reported extracellular cellulose activity of Fusarium graminearum isolates [22].

3.2. Effect of Nitrogen Source and pH

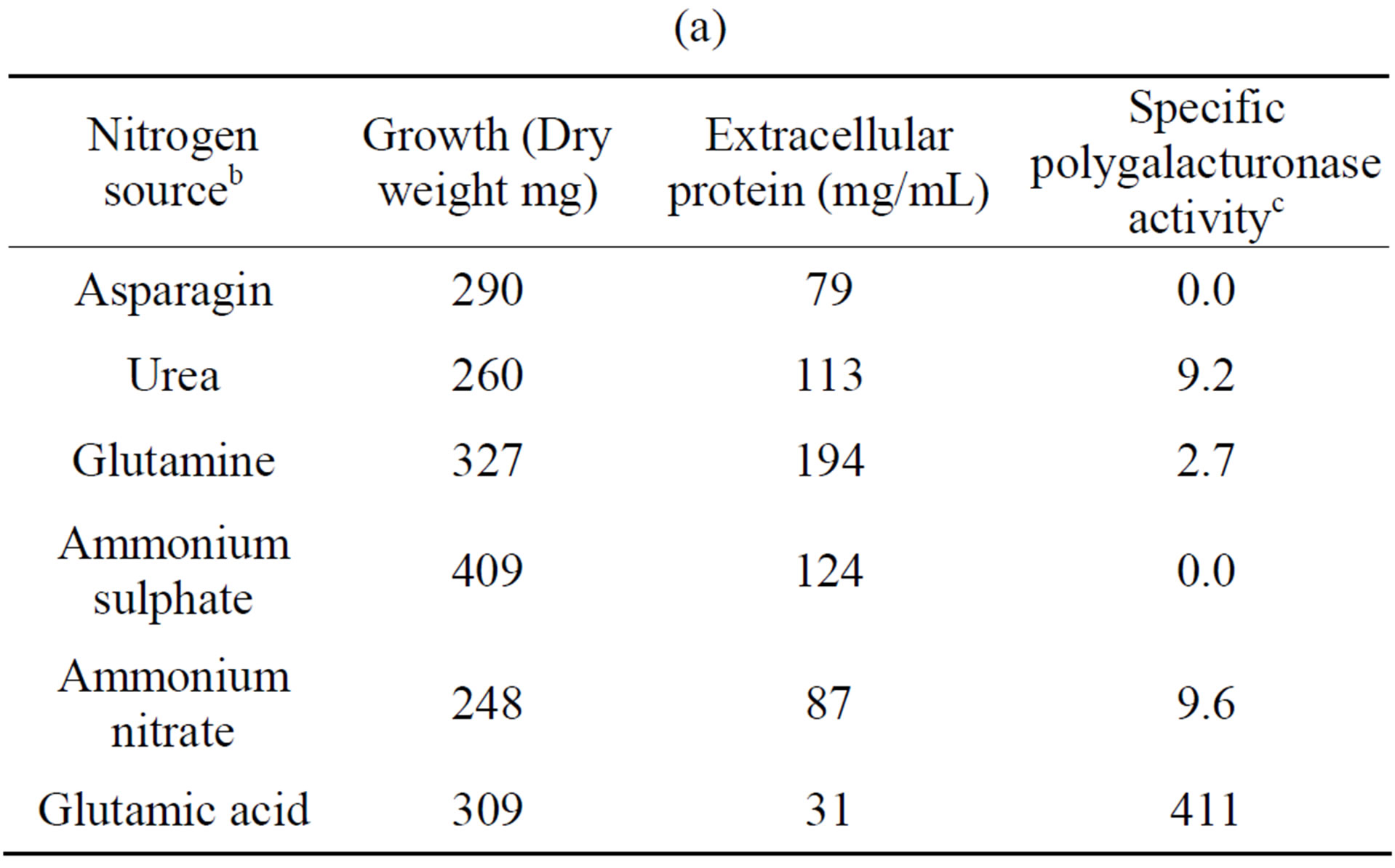

The influence of nitrogen source on growth and activity was also examined. Although comparable growth was observed with glutamine, ammonium sulfate and urea, and least with glutamate, this was by large the preferred nitrogen substrate for production of polygalacturonase,

(a)

(a)  (b)

(b)

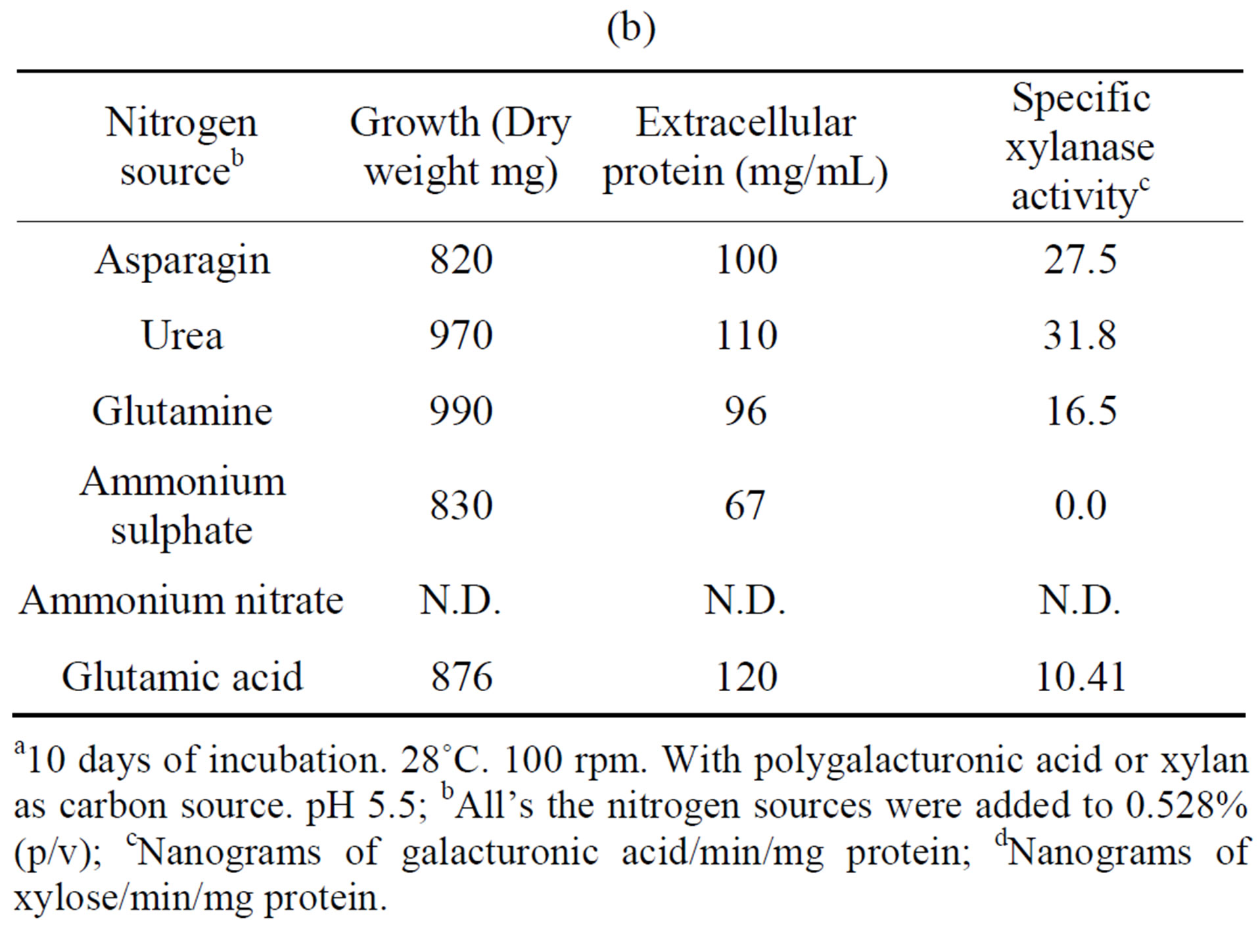

Table 4. Growth of Fusarium solani with different nitrogen sources and induction of extracellular polygalacturonase and xylanasea. (a) Polygalacturonase; (b) Xylanase.

a10 days of incubation. 28˚C. 100 rpm. With polygalacturonic acid or xylan as carbon source. pH 5.5; bAll’s the nitrogen sources were added to 0.528% (p/v); cNanograms of galacturonic acid/min/mg protein; dNanograms of xylose/min/mg protein.

and urea for xylanase (Tables 4(a) and (b)). Substitution of glutamate and urea by other nitrogen sources resulted in poor growth and activity and inorganic substrates such as ammonium nitrate and ammonium sulfate reduced activity drastically, as compared with glutamate.

In some organisms such as Stachybotrys elegans [23] and Thermomonospora fusca [24], growth on inorganic nitrogen sources resulted in low enzyme activity whereas in Saccobolus saccoboloides best growth and cellulolytic activity were obtained with asparagine, urea and casamino acids [25], and in Colletotrichum lindemuthianum the best nitrogen source was glutamate [26].

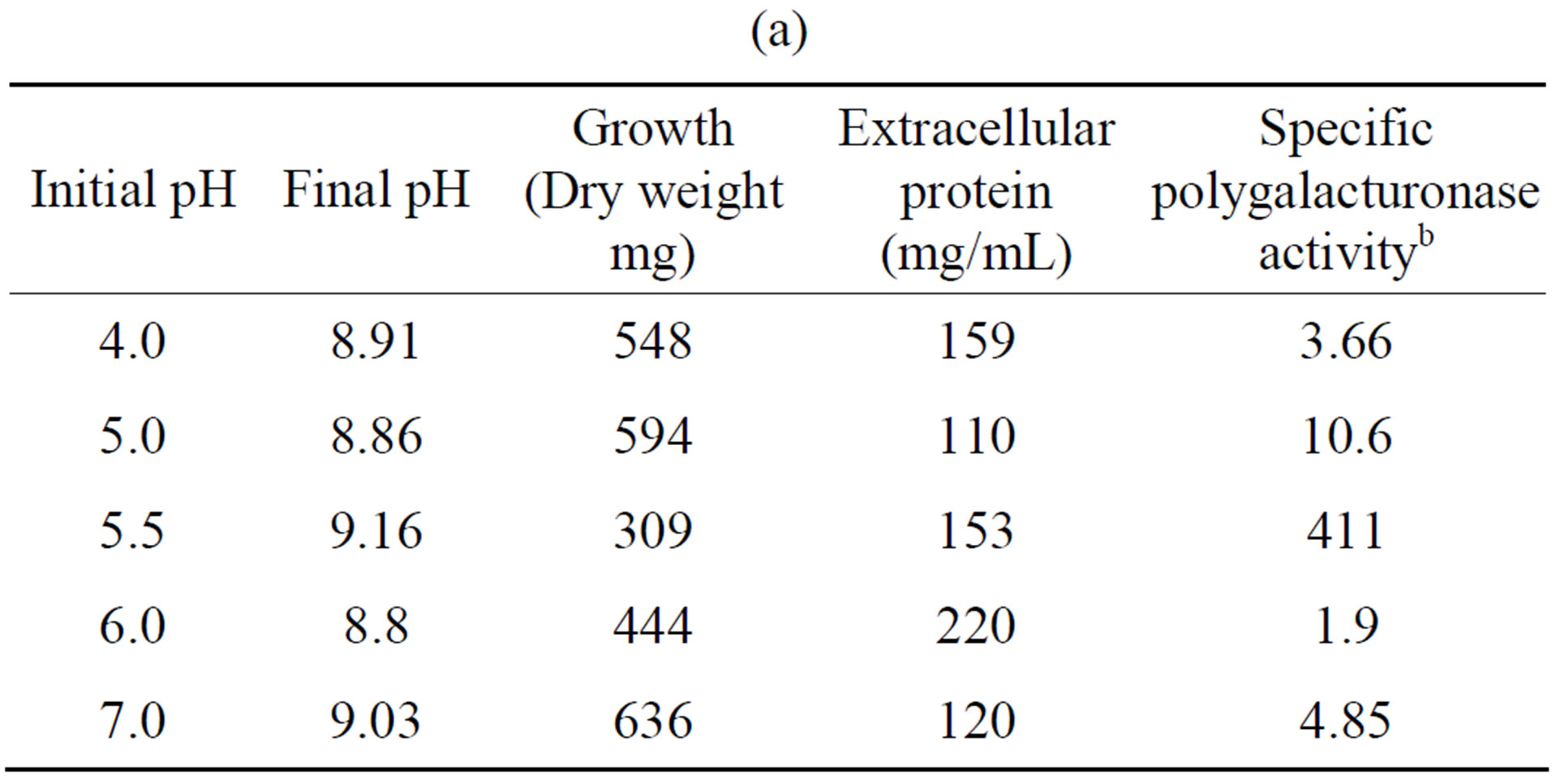

Tables 5(a) and (b) show that the most activity of polygalacturonase and xylanase produced by the fungus F. solani, exhibited an initial pH optimum of 5.5, while a higher growth (in mg dry weight) were observed at different pH’s of the optimal initial, and this results are similar to different reports [23,26].

3.3. Effect of Temperature and Protein Concentration

The optimum temperature for activity of extracellular enzyme activities was 60˚C and 45˚C for polygalacturo

(a)

(a)  (b)

(b)

Table 5. Effect of initial pH on the growth and induction of extracellular polygalacturonase and xylanase of Fusarium solania. (a) Polygalacturonase; (b) Xylanase.

a10 days of incubation. 28˚C. 100 rpm. With polygalacturonic acid or xylan as carbon source. 5.28 g/L; bNanograms of galacturonic acid/min/mg protein; cNanograms of xylose/min/mg protein.

Figure 5. Effect of the temperature on the activity of extracellular Polygalacturonase and Xylanase of Fusarium solani.

Figure 6. Effect of the protein concentration on the activity of the extracellular Polygalacturonase and Xylanase of Fusarium solani.

Table 6. Summary of the characteristics of induction of extracellular polygalacturonase and xylanase of Fusarium solani.

nase and xylanase, respectively (Figure 5), and these results are consistent with those reported for the fungi C. lindemuthianum [26], Neurospora crassa and Penicillium sp [27], and Trichoderma reesei [28]. It has been suggested that the temperature response for different types of extracellular lytic enzymes, is that as isoenzymes found in different species, with different properties [27]. With respect to the saturating concentration of enzyme, these parameters were 30 and 49.5 µg/assay for polygalacturonase and xylanase, respectively (Figure 6). We not found reports in the literature related to the topic.

Table 6 shows a summary of the results, showing the different induction times, which nitrogen sources are more efficient and are very stable at 0˚C and 4˚C.

Finally, it has been reported that polygalacturonases and xylanases are very important in pathogenesis, because the degradation of polygalacturonic acid and xylan is performed in early stages of infection, however, when some of the genes encoding polygalacturonase and xylanases are mutated, reduces virulence of F. oxysporum in tomato [18]. Too has been suggested that these enzymes are important in the pathogenesis of some microorganisms [6,7,10,18,29,30], and recently, has been reported an alcohol dehydrogenase involved in fungal virulence of Fusarium oxysporum [31].

4. Conclusion

In the present study, we established the best conditions for the induction of extracellular activities of polygalacturonase and xylanase in Fusarium solani. The maximum time of induction was of 10 and 13 days respectively, which is relevant because there are few reports, and both were very stable at 4˚C. Both activities are better induced with glutamate and urea as nitrogen sources respectively, and both exhibit an initial pH optimum of 5.5, an optimum temperature of 60˚C and 45˚C, and a saturating concentration of enzyme of 30 and 49.5 µg/assay, respectively. Finally, we didn’t find cellulase activity in the analyzing conditions.