Three-year follow up of primary health care workers trained in identification of blind and visual impaired children in Malawi ()

1. BACKGROUND

Blindness in children, although rare, is one of the priorities in the VISION 2020 initiative [1-4]. There have been changes in the global epidemiology of childhood blindness since the initiative was started [2,4-6], with a shift from those conditions that can be primarily prevented (such as vitamin A deficiency) to conditions requiring early diagnosis and medical or surgical management (such as cataract). Prevalence of blindness in children varies from region to region, with the least developed regions such as sub-Saharan Africa having a prevalence of between 1.0 and 1.2 blind children per 1000 child population [6]. Cataract is the commonest reversible treatable cause of blindness in children resulting in visual recovery, but delays in presentation can lead to long standing consequences that may permanently impair vision [7]. To increase earlier diagnosis and access to paediatric eye services, efforts at the community level have included training of key informants [8-16] and primary health workers [17] to identify and refer children in need of service. Key informants (KIs) have been used in a “campaign mode” while primary health care (PHC) workers are an integral part of the healthcare system; this difference may provide the primary health care worker approach an advantage in the long term. However, two studies that compared the effectiveness of KIs to primary health care workers in Africa demonstrated that KIs identified far more children than PHC workers [17,18]. Additional work in Tanzania on knowledge and skills in regard to blindness in children among health workers has shown a deficiency in both knowledge and skills attributable to a number of factors [19]. Nonetheless, there is still a lot of continued interest in using PHC workers to identify and refer both children and adults for eye health care. To ensure that sustained and productive child eye health services are offered to communities in future, and it will probably require innovative ways of using both the KI and PHC worker methods to complement each other.

In Malawi primary health care workers known as “Health Surveillance Assistants” or HSAs are the frontline health care providers employed by government to work in the community; with each responsible for around 2000 to 10,000 population [17]. They are secondary (high) school graduates who attend three months of para-medical training aimed at providing basic skills to conduct maternal and child health (MCH) activities such as immunisations and child growth monitoring [20-22]; and many other general activities such as sanitation, water source protection and water treatment [23], disease surveillance, village inspection, community health and nutrition talks, supervising village health and water committees, providing family planning, and following up chronic patients needing palliative care in the community such as TB patients, AIDS patients and cancer patients [24]. However, due to their short training, HSAs are not officially recognised as clinical personal and hence are not registered by medical and nursing bodies in Malawi.

In regard to referring cataract children, HSAs would be expected to identify such children in the community, referral then to the health centre, then district hospital and finally the tertiary eye hospital in Blantyre. Currently there is virtually an absence of referral of cataract children from the communities in Malawi using the system of HSAs, as they are not trained in childhood blindness, and this is evidenced by absence of records of children with cataract who come to the eye hospital identified by HSAs. It is the lack of this system that prompted exploration of different ways of how to get cataract children identified from the community and referred to the tertiary hospital as soon as possible.

In 2008 Mulanje District (population 521,391) in southern Malawi was selected for a project in which HSAs were trained in diagnosis and referral of children with severe visual impairment and blindness, with a focus on increasing referrals of cataract blind children. The aim of that study was to compare, in the short term, the referral rates of children among HSAs and KIs, and the results of the study have been reported elsewhere [17]. The current study was a follow up from the earlier study, with the aim of determining the attrition rates of the HSAs, and assessing the number of referrals over the long period and determining the retention of knowledge on blindness in children, specifically related to visual acuity and cataract in children that was provided in the earlier training.

2. METHODS

Ethical permission to do the study was obtained by College of Medicine Ethics Committee (COMREC) in Malawi. This was a cohort study with 59 Mulanje District HSAs (covering a catchment population of 238,454, of whom half are children below 16 years) trained in 2008 in childhood blindness identification and referral, with a primary focus of getting cataract children for surgery early. The HSAs were assessed before and after the training in 2008 in regard to their level of knowledge about childhood cataract and blindness in children in general, which was minimal (less than a quarter new that cataract would occur in children, and none knew that surgery was indicated for cataract in children), but increased markedly after the training. Training was approximately 8 hours in length (one full day), using a standardised KI/HSA manual, based on experiences and protocols that that had been developed earlier in Malawi and elsewhere [10,11]. Training materials and methods included lectures, posters of eye conditions, flip charts, demonstration and practical instruction on testing visual acuity in children (with a vision chart provided to each one of them), discussion and group work. Training emphasized the causes of blindness in children and their management, how to assess visual acuity, identify and refer children they suspected of being blind, and how to identify blind children with normal-appearing eyes. Upon completion of training each HSAs received an illuminated snellen visual acuity chart, a summary brochure of things learnt and forms to be used for referral. Using the KI protocol, follow up and reminders were done at 3 weeks and 5 weeks (using a phone call) and for those HSAs who identified children, examination of children by the team from Blantyre was done at 6 weeks in set centres within the community. This had been tested and was found to working when using key informants [25]. HSAs who may have identified any children would therefore have had at least once chance of being supervised in the community. From then onwards they had to call and inform the organising team every time they identified and referred a child. The cohort was reassessed 3 years later in August-December 2011. During the interim period, the HSAs did not receive any special supervision or additional training regarding childhood eye diseases.

Each HSA was contacted again in 2011 through his supervisor and a time was set up for a telephone interview. Where HSAs could not be located in the original community, their whereabouts were ascertained from their supervisors at the district health office in Mulanje or through colleague HSAs. It was decided that during the phone interview, only a few clear, simpler follow up questions that could reliably attempt to give some useful information should be used in order to minimise recall bias. As part of primary eye care work, a PHC worker while working in the community would need to know that a visual acuity chart has to be used to quantify how much a child can/cannot see, know at what distance the chart should be used, and be able to detect a child with cataract and refer immediately. If one did not have the basic knowledge in assessing visual acuity (VA) and on what cataract is, they would not be able to perform any useful skills in identifying cataract. Therefore testing HSAs basic knowledge on VA and cataract would serve as a proxy for testing their skills (which cannot be done through phone interview). The questions were pre-tested through eye workers at the eye hospital in Blantyre, refined and finally used on HSAs, while acknowledging the limitations of using them in testing skills.

The interviewer used a structured questionnaire, starting with explaining the purpose of the interview, obtaining informed consent through phone and proceeding as follows: collecting demographic information, asking the HSA to state whether they had been trained, asking questions about measuring vision (to see if the HSA remembered the use of a visual acuity chart and what distance it should be used), and asking about management of cataract in children (surgery). The HSA was finally asked if he was still involved in identifying children. Data from the questionnaire were entered into MS Excel for analysis.

3. RESULTS

Among the 59 HSAs trained in 2008 all 29 male and 25 of the 30 female HSAs (54 total, 92%) were traced and interviewed. Among the 5 not interviewed one had died and four had moved out of the district and could not be found. Among the 59 original HSAs 42 (71%) were still working in the same health centre, 10 (17%) had gone to another health centre in Mulanje, and 2 (3%) had gone to a health centre in another district.

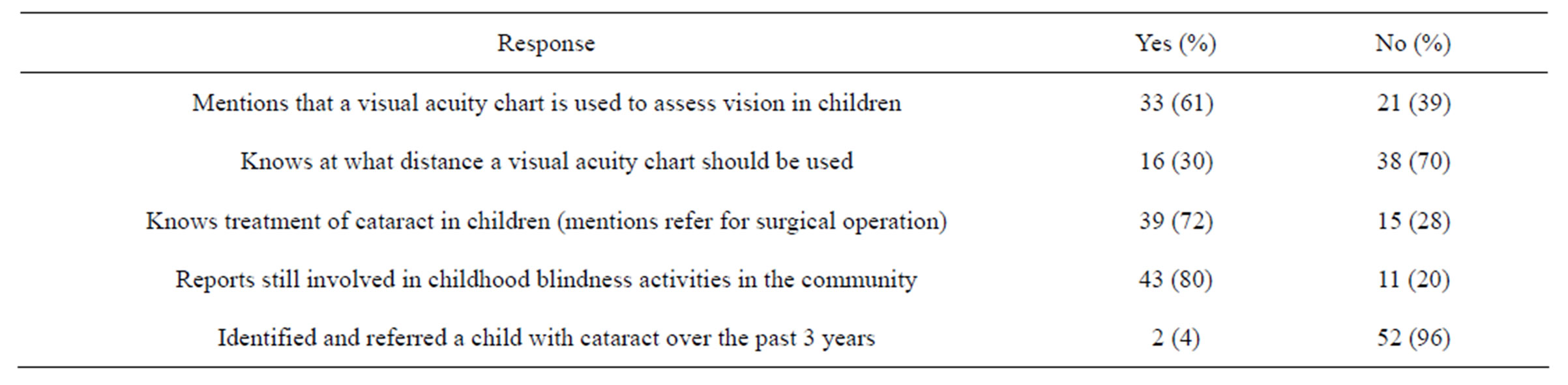

Theoretical knowledge about childhood blindness (correct responses on the questionnaire), are shown in Table 1.

While most HSAs reported that they were still “involved” in childhood blindness activities only 2 reported actually referring 2 children (one child each) they suspected of having cataract and the rest reported that they had not identified any child needing referral.

4. DISCUSSION

This study was carried out to determine the attrition of primary health workers after training, and to assess their knowledge and skills on cataract in children, and determine whether the training in childhood blindness has long lasting effects on the practices of HSAs in the community. HSAs have been said to be the backbone of the health system in Malawi, with numerous efforts and resources being given to build capacity of HSAs in primary health care. For the community, HSAs are preferred to volunteers (key informants) as volunteers are not employees and not a recognised part of the health system. There is limited information on the short and long term benefits of using HSAs in blindness prevention in children in Malawi, and without this supporting information, it may be justifiable to explore other alternatives such as the Key informant method.

It was encouraging to find that 54 of the 59 HSAs were still working, as attrition has been noted to be one of the major factors contributing to human resources crisis and a major obstacle hindering effective health service delivery in Africa, with some workers even moving from health into non-health professions [26]. In the case of HSAs, however, one must consider that they are not an officially recognized cadre of clinical health workers and this may limit their opportunities to work elsewhere.

It was encouraging to find that 75% of HSAs remembered that surgery was required for cataract in children, considering that probably less than one quarter of the untrained HSAs would know this. Only a few (61%) remembered that a visual acuity chart could be used with children and fewer still (only 30%) knew the distance at which the chart should be used. Of course, this should be

Table 1. Responses to questions regarding blindness in children.

balanced against the fact that visual acuity charts are not useful with pre verbal children, which is the most important group to identify. The younger the child is the more skill required to assess his visual acuity; we do not now recommend training primary health care workers to measure visual acuity in children, believing it is more useful to ask the mother or caretaker whether she thinks the child sees properly (in fact, this is the method used to train KIs). Unfortunately, in many sub Saharan African countries, delay in presentation is such that children are old enough [7] to test with a chart by the time they get into the health system and this is the reason it was included in this training. In our experience, however, accurate visual acuity testing is a skill surprisingly difficult for most primary health care workers to learn even for adults and for children it is unrealistic and possibly confusing and misleading.

The finding that only 2 HSAs had identified and referred a child suspected to have cataract in the 3 years after their training is not encouraging. The prevalence of blindness in children in this population is estimated at 1 per 1000 children [27], with approximately one third of these having cataract. The precise data for incidence of childhood cataract in Africa are not available, however, in a catchment area of 238,454 (half of whom are children) covered by the HSAs, it can be estimated that there would be approximately 40 prevalent cases (1/3 of all blind cases) of childhood cataract and additional number of incident cases for each of the 3 years, half being congenital and half developmental cataract [9]. Thus, in the three years of the project, HSAs could potentially have identified and referred some of the 40+ children requireing intervention. We do not know whether the HSAs failed to recognize the problems or whether the children did not pass through their care. If it was the former, then we cannot be certain from this study whether the HSAs never had the practical skills to recognize cataract (white pupil) after their training or whether they actually did not look properly for this condition back in their positions. However we can confidently say that it is very unlikely that it is the short length of the training (8 hours) that has hindered/prevented HSAs from identifying children as in comparison to KIs who are subjected to the same length of training, HSAs productivity is much less [11]. Given the rarity of the condition, the technical difficulty of examining children (especially the youngest), and the many competing tasks an HSA is supposed to perform, one should question whether it makes sense to train HSAs in physical diagnosis of eye conditions in children at all. The goals of training for HSAs regarding primary eye care for children need to be seriously considered before allocating more resources into training. The study has limitations in that it used knowledge obtained using telephone interviews as a proxy for determining HSA skills and it would be advisable in future to replace telephone interviews with direct clinical observations to accurately document the lack of skills.

The situation is certainly not hopeless though, as demonstrated by the successes of KIs [10,11,18]. Coupled with the use of dedicated ophthalmic personnel (midlevel workers) and a good referral system, this option offers real possibilities of identifying children with visual problem early and ensuring they receive treatment.

5. CONCLUSION

Despite attrition among primary health care workers being low in Malawi, only a few actually identify cataract children in the communities after being trained. Other innovative ways such as the use of key informants are needed to identify prevalent and incident cases in Malawi, as the use of HSAs is unlikely to be successful in addressing blindness in children.

6. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the British Council for Prevention of Blindness for financially supporting the original work that led to this study, which was financed by BICO. We thank the District Eye Coordinator for Mulanje district for providing us with phone numbers of Clinical Officers and Medical Assistants. Many thanks the Clinical Officers and Medical Assistants for linking us with the HSAs whom we did not have their contacts.

NOTES

Authors’ contribution: KK: Designed experiment, performed analysis and wrote manuscript. MN: Performed experiment. SL & PC: Reviewed manuscript.