The Initial 40 Years of the EC Maritime Policy, Part I: 1957-1997: Is EU-27 Maritime Industry “Fit for 55”? ()

1. Introduction

The “Treaty”-T, which established EC1 signed by 6 nations in Rome in 25th March, 1957 (Photo 1).

The main targets of the EC-T-1957, after 2 deadly2 global wars, were six (Graph 1):

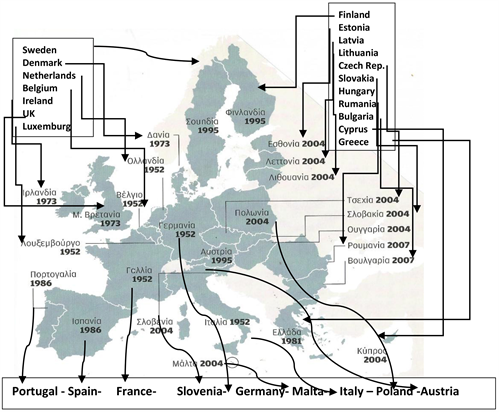

The member-states which consisted EU-28, and their year of accession (Table 1), is shown.

(Scan 1) It took 16 years, (till 1973), for EC-6 to be enlarged, due also to a 12-year transition period (till 1969). For EU-27’s further transport integration, we believe, Serbia must be accessed. Certain—especially non-monetary, but cultural targets—have further to be pursued… The effort of…“Europe-zation” was really a great task, though certain elements uniting European People existed like: “Peace! No War”!

The elements dividing Europe were/are also important: 1) the war among certain European nations in 1940-1944 (against Germany3; Italy4; Bulgaria etc.); 2) the diverse history (Greece5); 3) the different religion; and 4) the dual “working attitude” between North and South.

![]()

Graph 1. The main targets of the EC-6-T-1957. Source: author.

Photo 1. The 6 original members of the EC, 1957, signing… Source: modified from that in “About Europe”, EC publication (in 1982?).

Scan 1. The geographical picture of EU-27, 2007. Source: “Kathimerini” assisted by the EU office of the Commission (Greece); modified.

![]()

![]()

Table 1. The nations consisting the EU-28 and the year of their accession, 2020.

Source: internet. (*) UK withdrew from the EU-28 on 31st January 2020; (**) Strong offshore flag; (***) Strong offshore fleet.

The idea of forming the EC-6, we believe, was to “make” all Europeans… “brothers”! We saw, however, that the dividing nationalism never went away… The EU-6 tried to become a “family”, where…Germany was (is) the father, and France was (is) the mother! One child is Italy, while the other (UK), left the family. The father believes that…to be in this Union, means to work as hard…as Germany! Brothers in the North believe, more or less, the same. Brothers in the South, however, believe that life has and other interesting endeavors...

Moreover, if in EU-27 existed one religion, namely that of “Christian Orthodoxy6”, we believe, it could decisively help7 the European vision. In addition, the individual nationalities, we believe, did not fallback, and one8 “European nationality” did not become dominant; though any discrimination on grounds of nationality was indeed against EC-6-T-1957.

Unfortunately, EU-27 failed to put aside national interests in favor of solidarity! Germany and Spain sell arms etc. to Turkey in 2021, which Turkey threatens Greece with war. This is a clear case of nationalism9…and anti-solidarity.

Certain important positive steps were taken by EC-1510 (Table 2), no doubt:

2. Aim and Structure of the Paper

The aim of this paper is to analyze, with a critical attitude, the EC-6-15 common shipping and maritime policy, during its first 40 years (1957-1997). Also, to present the recent EU-27 “fit for 55”.

![]()

Table 2. The positive steps taken by EC-15.

Source: author. (*) Something we disagree.

The structure of this paper is as follows, after literature review: Part I deals with the power of maritime EC-9-28. Part II deals with the tools that EU-15 adopted to carry-out its duties and solve its problems. Part III deals with the EC-6-15 period of 27 years of inertia to form a CSP/CMP (1957-1984). Part IV deals with the laying-down of the foundations of a CSP/CMP (1985-EC-10). Part V deals with Commission’s communication “towards a New Maritime Strategy” (1996; EU-15). Part VI touches upon the future Common Marine Policy-EU- 25-27 (1998-2021). Part VII deals with the “fit for 55”. Finally, we conclude.

3. Literature Review

Couper (1977) admitted that the EC-6-Treaty-1957 contained no official shipping policy. Article 84 (2), however, gave the Council the power to decide on sea transport issues. Additionally, some general Treaty principles, related to monopoly and preferences, could be also interpreted as applying to shipping—but this was a view not shared by all member-states.

Captain Spartiotis (1980) of the Greek Ministry of Mercant Marine11, argued that the EC-9 CSP started in 1974, with the “Court case” of the “Commission vs France”. In fact, the relevant cases were 3 (Graph 2).

Spartiotis also argued that there were 2 economic policies in EU-10: one supporting the “state-intervention”, carried out by Commission, and the other supporting “economic liberalism”. Apart from the above 2 opposite economic philosophies, role played also the national interests and the expediencies…of the member-states.

Farthing & Brownrigg (1997: pp. 62-67) argued that the “1987 single European Act”, amending the EC-6-T-1957, completed the “single European market” and lowered further any remaining barriers among member-states, so that to form an “open market” (by 01/01/1993). The “Maastricht-T”-1991 extended the powers of the European Parliament, and provided the CM increased votes, by the majority rule (Table 3 & Table 4)!

![]()

Graph 2. The 3 cases giving an impetus towards an EC-10 CSP-1974-1985. Source: author.

![]()

Table 3. The effects of the “Single European Act”-EC-12, 1987.

(*) Plus, a common discussion with the newly formed ‘‘Economic & Social” committee.

![]()

Table 4. Effects of the Maastricht Summit, EC-12.

The institutions of the EC-12 strengthened in Maastricht. A “single market” surely needed the free movement of the factors of production, including capital. But the free movement of labor was theoretical, we believe, for EU-12’s manpower, due to existing different languages, diplomas12 and other barriers. The aim of the “Maastricht-T”-1991 (EC-12), was a more intense integration in the monetary area with one common currency, one defense, and one common foreign policy. At the moment, NATO13 protects EU-27 and FRONTEX its borders.

The EC-12’s benefits, however, were not without a cost: member-states gave-up part of their sovereignty, in general, and in maritime issues, in particular, and their Parliaments weakened, because the laws of the EU override those of the member states. A rich source of knowledge about EU-15 is Power (1998), used also for writing this paper.

Stopford (2009: pp. 88-89) argued that EU-27 wanted to apply its regulations also to dry cargo companies & their pools. Competition, which was regulated by articles 81 & 82, ruled as illegal the companies which prevent, restrict and distort competition by fixing prices, manipulating supply etc. (p. 690). In 1962 regulation 1714 gave EC-6 the power to enforce articles 81 & 82, except in sea transport (& Air)!

Casaca (2012) argued that the different communications from EU-27 showed that maritime transport needed integration, especially in the multimodal/inter- modal transport chains, but in a rather systems approach. She provided a detailed account of CMP from 1957 to 2012. She also provided 96 references published by majority by the Commission! Goulielmos (2012) edited a special volume titled: “European marine affairs after world economic crisis”—meaning after 2008.

Summarizing, the equalization of salaries and wages in EU-28, which was a dream, especially of the South, remained…a dream15. Moreover, 16m of Europeans were unemployed (Oct. 2020)! The economic crisis of 2009-2018 equalized labor supply among member-states, as many e.g., qualified Greeks, sought employment in EU-27!

4. Part I: The EC-9-EU-28, as Maritime Power

4.1. The EC-9 Fleet (1974)

This was 3rd worldwide (Table 5). In cargo-generation16, EC-8, held 23% worldwide, where 63% of it was attributed to only UK, Germany and Netherlands, followed by France (~4%).

The EU-8 failed, however, to maintain a leading shipbuilding17, as it used to have, something we consider to be a great disadvantage, because a union’s competitive shipping cannot be without a union’s competitive shipbuilding! EU-27 must think this important issue over again.

4.2. The EU-25 Fleet in April-2005 (Figure 1)

As shown, 6 out of the 25 member-states, had a fleet % greater than 10% of the total (Cyprus, Greece, Malta, Germany, Italy and UK) which was 195m dwt in April-2005. Three member-states (Cyprus, Greece, Malta) had 125m dwt, or 64% of the total. Eleven member-states covered almost the 97% of EU-25 tonnage. In more detail (Table 6):

![]()

Table 5. The shipping countries and their share worldwide, in GRT, 1974.

Source: Inspired from Farthing & Brownrigg (1997).

![]()

Table 6. The shipping profile of 8 from the EU-25 member-states, 2005.

Source: internet.

![]()

Figure 1. The EU-25 fleet in dwt (01/04/2005). Source: internet.

4.3. The EU-27 (2019)

This is the number-one global shipowner, stronger than G-20, where almost 16% of the world fleet is owned by EU-28 (313m dwt). European ports served 1.3m arrivals of ships (>1000 GT) in 2018, almost 1/3 of the world (~31%). In 2008, the Ports of the EU-27 handled ~3.8m tons (3.3 in 2003), where Rotterdam had the lion’s share (10%). In shipbuilding, leaders were first Japan19, then S. Korea and now China. Greeks are recognized as the most competitive international shipowners (Goulielmos, 2021a), and for their laissez-faire policy.

5. Part II: The Tools EU-15 Had to Carry-Out Its Duties and Solve Its Problems

5.1. The EU-15 Tools

EU-15 established certain tools in order to carry-out its duties (Table 7).

5.2. The Article 148 of the EC-6-Treaty

This dealt with the qualified majority…in order for the “Council of Ministers”—CM to…act. This majority required 71% of the 87 votes of the EU-15 (62 votes). However, the 4 larger countries were dominant in EU-15, because: Germany, France, Italy & UK had 10 votes each (=46%)! One medium country had 8 (Spain); 4 small countries had 5 each (Belgium, Greece, Netherlands & Portugal); 2 countries had 4 (Austria & Sweden); 3 had each of 3 countries (Denmark, Ireland, Finland); Luxemburg had 2.

(*) The most measures which affect shipping are either regulations or directives.

5.3. Equality and Brotherhood

Surely these are not characterized by the above voting system! All 27 member-states, we believe, should have 10 votes (=270), and then the qualified majority to be 75% (202 votes). Elsewhere, we have criticized the above voting system, for maritime issues, if we assume that votes had to be allocated in accordance with the tonnage owned! Greece, Cyprus and Malta owned more than 174m dwt in 2018 (~60%).

5.4. Immigration

Today, EU-27 cannot keep its borders watertight to immigrants (Figure 2) coming from Turkey and/or Belarus and from elsewhere. Modern wars seem to be over immigration, data and energy!

As shown, 4 member-states bear a greater immigration burden: Malta, Luxemburg, Cyprus and Ireland…Malta has in every 1000 citizens 50 immigrants. In EU-27 were about 23.30 million immigrants in 2018, with a trend to increase after the end of the Afghanistan war.

5.5. EU-27: A “Prisoner” of Russia?

Moreover, the EU-27 is indeed an energy…“prisoner” of Russia, through the supply of natural gas! EU-27 has to build a self-sufficiency in green energy the soonest possible!

6. Part III: The EC-6-EU-15, 27 Years of Inertia to Form a CSP/CMP (1957-1984)

The EC-6-T had a “timetable” with 20 chapters. One, titled IV, devoted to a “common transport policy”—CTP. It declared that the provisions of the EC-6- T-1957 will apply only to rail, road and inland waterways! Sea (& Air) have to

![]()

Figure 2. EU-27 Immigrants, 2018, per 1000 inhabitants. Source: Eurostat; Est. = estimated; Prov. = provisional.

wait till the CM would decide, by a qualified majority, (article 84; meaning then 62 votes out of 87 or 71%)…!

6.1. The Importance of Shipping (for EC-6)

The EC-6, despite the exclusion of shipping from the EC-6-T, recognized its significance on 4 important aspects (Graph 3).

As shown, the EC-6 appreciated the role of Shipping Industry for providing employment to EU-6 citizens, approaching today the 2 million persons worldwide for total global fleet (on board; let alone the “land maritime employment”20).

According to seafarers’ statistics21, in the EU-28, in 2019, were 216,000 masters and officers22, certified by EU-28 member-states, and 120,590 not certified by member-states (336,590). Since 2016, more than 70,000 masters and officers added23!

Shipping industry is also a provider of foreign currency, as it earns its income mainly in USA $. In 1974 this estimated24 as equal to ?3b. Moreover, EC-9 shipping carried almost 70% of EU’s internal trade, and 40% of its external one.

6.2. The Reasons for EC-6’s Delay to Decide a CSP/CMP (1957-1984)

A common shipping policy-CSP, or more correctly, a common maritime policy-

CMP, “appeared” 27 years after EC’s formation, i.e., in 1984! The reasons why a CMP delayed for almost 30 years, are not known, but there are 3 official speculations, as well our arguments (Graph 4).

As we derived indirectly from the “Seefeld report”, a CMP had to include EC-6 Ports, but this was extremely difficult, perhaps due to the “state aid” ports were receiving. Thus, a common port policy-CPP was not possible in 1957. This, however, was a serious handicap because as Goulielmos (2021c) wrote, the port costs (65% in total ship operating cost) were/are extremely high and different among EC-6 ports for the same service!

This was a dear opportunity to make EC-6 shipping more competitive, a result so much sought after by the Commission! This could be done, if EC-6 ships had e.g., special uniform low port expenses…in all EU-6 ports for the same services! Ports are the dominant partners of shipping industry! The less ports and shipbuilders gain, as well others (canals etc.), the more shipping becomes profitable.

![]()

Graph 4. The reasons which perhaps prevented EC-6 to negotiate, at Val Duchesse, a CMP (1957). Source: WD, (working document), No 5, end-March, 1977. (*) The UK transport commissioner made publicly his misgivings about the influence of Greeks! He wanted a more pronounced statement over the labor issues & flags of convenience25!

Ports, however, as being local and national have much higher power to their governments…than ships.

6.3. Building a CSP, 1970-1980

There were 8 reasons which played their role to form a CSP (Graph 5)26,27,28.

![]()

Graph 5. Factors, which indicated a need for a CSP, 1973-1981 (Photo 2). Source: Author; inspired by Power (1998: p. 137) & thereafter; (*) Owning 1/2 of the EC-6 fleet; UK owned ~32m GRT & Denmark 4.5m in 1975, a total of ~65m dwt. (**) Certain shipping analysts argued [(Spartiotis (1980)

![]()

Photo 2. Greece signs its accession treaty, May 1979. Source: “About Europe”, modified; the accession of Greece (1981)29; the effect on its shipping was neutral.

The EC-6 enlarged in 1973, and as a result EC-9 sea trade carried up to 90% by EC-9 ships30. The “EC-6 Parliament” adopted, (in 1972), a Resolution, based on the “Seefeld” report31, mentioned above, pointing-out the need for a CSP, in view of the 1973 enlargement! In end-1975, France also addressed to CM, saying—among others—as to how a CSP had to be drafted (point 451)! Pressure from inside was increasing on Commission.

In 1976, the Committee of the EC-9 Parliament on “economic & monetary affairs”32 reported on the existing oil crisis, and on the million dwt of tankers laid-up (about 35m dwt in end-1976)33. Also, on tankers disasters, in 1970-1980, of which many near-by EC coasts (Goulielmos, 2001)!

The EC-9 Council, (1978), adopted a recommendation on the ratification of the most important 4 international IMO conventions of safety and pollution! This last action had to be taken before, as these important conventions were adopted by IMO 4 - 5 years earlier!

All the above were the preparation stages towards a CSP/CMP till end-1984.

7. Part IV: Laying-Down the Foundations of a CSP/CMP, 1985-EC-10

The CSP/CMP was based on 4 measures (Graph 6). The Presidency of the CM, in Dec. 198634, held by UK, to which Greece also contributed. The issued regulations completed the foundations of the EU CSP/CMP (known as “Brussels Package”).

As shown, ~28 years of inaction led—within about 11 years—to 4 proposals of a CSP/CMP (1985-1996)!

![]()

Graph 6. The pillars of the CSP/CMP foundation, 1985-1996: the Brussels package, EC- 12-15. Source: author. (*) Bulletin of the European Communities, suppl. 5/85. (**) O.J. No. L 378, 31/12/1986. (***) Com (96) 84, 13/03/1996.

The CMP: Starts in March, 1985 (EC-10)

Commission communicated a memo35, representing the 1st systematic attempt to design a CSP, laying-down the main lines of action for EC-10. Till then, no one, (Commission or Council), defined clearly an even general, framework, for a CSP! The communication dealt with36 (Graph 7):

The communication confirmed EU-10’s shipping overall principle of “laissez-faire”, and its opposition to cases of cargo reservation, where a permission asked to undertake action. The freedom to provide shipping services concerning the: Offshore industry; EU-10’s trade with 3rd nations, and “cabotage”37, which concerned in particular Greek Coastal Shipping!

The above was based on the assumption that by “liberating” shipping markets, (except liners38), a more intense competition will prevail39 among ship-owners, which will make charterers able to offer cheaper40 goods to final consumers… through a lower transport cost. However, Supply and demand only determine transport cost as it is known to those living in Jerusalem!

● The Commission enthusiastically attended Maritime Safety and the prevention of sea pollution by ships, by adopting what conventions existed 4 - 5 years already! This was easy!

It put also an emphasis on:

● A Port State Control, the Substandard ships and Crew’s working conditions.

● The coastal navigational systems & hydrography.

● Helping developing countries to train their masters, crews and maritime administrations—something of secondary importance—but of good public relations.

● The issue of ports, and the competition among them, and state aid41, which was important.

In the 2nd-half of 1981 (EC-10) started a “deep & prolonged shipping cycle”, till the 1st half of 1987, affecting the dry cargoes (EC-12). The ECOSOC committee found that the then existing CSP was: deficient, static, unpragmatic, unrealistic and unaware of the changes occurred, or occurring, in Trade42! This indicates

![]()

Graph 7. Proposals for progressing towards a CMP, the 1985-Regulations, EC-10. Source: Author.

that till 1985 (EC-10) the Commission lacked a coherent and comprehensive CTP…

➢ The 1st stage towards a CSP

The “1986 package” (EC-12) brought-in 4 regulations (Graph 8), which were adopted by the CM. The aim was to maintain and develop an efficient and competitive shipping industry for the benefit of the EU-12-trade!

In more detail, in 1986, the EC-12-regulation 4055 applied the freedom in providing services to maritime transport, and regulated the relations of EU-12 with 3rd countries (cabotage excluded). Reg. 4056 laid-down detailed rules for the application of articles 85 & 86 of the EU-6-T to maritime transport. Also, for the negotiations with 3rd countries on unfair pricing policies. This excluded tramp shipping, considered to be already competitive; a view which repealed in 2006, and the tramp shipping’s exemption from pools also lapsed.

Reg. 4057 dealt with the unfair pricing practices related to dumping of maritime services (31/12/1986). Reg. 4058 concerned a coordinated action to safeguard free access to cargoes and to ocean trade. Liners considered as offering stable freight rates (true), and thus received a block exemption from Art. 81, and allowed to fix rates, regulate capacity and collude, for the time being for God’s sake!

➢ The 2nd stage of a CSP came 3 years after, in 1989, and took the title: the “Positive measures”43 (EC-12). This was a communication44 to CM not only to improve the operating conditions of EC-12 shipping, but also to complete the 1986 CSP. Two in one.

The 1974-1987 maritime crisis caused the fleets of the EC-12 to diminish, and shipowners asked for help, as usually do in such cases. Help tried, but with a considerable delay! EC-12 tried first to define who is the EC shipowner so that to be helped... For us, the “community shipowner”45 is the one, who registers ships

![]()

Graph 8. The 1986 Package of a CMP, EU-12. Source: Author.

in one member-state, but also registers other ships, in another non-EC-12 registry! Let us call this 2nd fleet: “transnational”!

Both above fleets should concern EC-12-no matter that a number of ships are under foreign flags, as both contribute to EC trade—and not only. EC (and member-states) it would be better to be concerned with the profits of community shipowners, and if these benefit their countries of birth or not! This is an important aspect which has been ignored46!

To those that could understand shipping, the measures required, since 1974, were, in our opinion:

● To boost trade i.e., demand,

● To reduce oil prices by disciplining OPEC47, and,

● To reduce costs of operation of EU-12 ships due to flag!

Certain member-states chose, however, the faster and easier way, i.e., to abandon national flags, for reasons of cost, and thus EC-12 fleet to shrink (Goulielmos, 2000).

In more detail, shipping industry decided to resort first to:

● Open registries, and,

● to Offshore ones.

In the first belonged the nations of Antigua, S. Vincent and Vanuatu. In the 2nd, Bermuda, Denmark, Isle of Man, Norway etc. These combined the prestige of their national flag with the benefits of an open registry (!), something that EU-12 could not come to grips with at the beginning. The offshore registries we think is a case of shipping “globalization”. The matter of safety is a matter where discounts cannot be permitted, and the example of the “international ship register of Norway” in 1980s is a successful example!

In 1987, indeed EC-12 shipping industry established parallel registries in order to face competition! These enabled shipowners to register vessels under the (dual) national flag, and at the same time to operate them with a much “higher degree of flexibility” under the parallel registry (Anastasopoulos (1987)

The “positive measures” were (Table 8).

As shown, from the 5 positive measures, only the last 2 were really positive. The “Hellenic Chamber of Shipping”48— HCS (1989), pointed-out that the intervention of certain commercial interests of one…member state49, made cabotage an issue in the PMs, while it should not! It (p. 5), however, excused indirectly the situation where competition, against EU-12 ships, came from EU-12 shipowners under non-EU-12 flags, (because only the “Far East countries” mentioned50).

HCS (p. 5) accused…PMs as being favorable to certain member-states! It further (p. 6) mentioned that the reduction of crew cost was not always the only reason to employ foreign crew, and to choose Asian crews. Member-states did not want to confront seamen’s unions.

HCS insisted in the principle—which is right at all times—for governments, and for EU-12, to avoid influencing shipowners in their managerial decisions51. This means par excellence “timing to buy ships”. It (p. 7) accused EC-11 for paying no attention to the problem, which was for EC-12 citizens to avoid shipping as an employer, for the last 30 years.

8. Part V: Towards a New Maritime Strategy, 1996, EU-15

➢ This had 4 new elements (Table 9)! To start with it was wrongly titled “maritime”, because it dealt only with “shipping”, excluding ports and shipbuilding.

Besanko et al. (2013: p. 1) argued that a strategy is, in short, “fundamental to an organization’s success, and its study is, or can be, profitable and intellectually engaging”!

The communication took the form of a resolution52. Its relevant issues were (Graph 9).

Commission found that a “common maritime safety policy”—CMSP, has been already established. The “external maritime policy”—EMP started. But, the competitiveness of the EU-15 fleet remained unsolved (1996)! Commission excused its dealing with only shipping, because another communication filled this gap53. Commission mentioned also the new development, which took place since 1985,

![]()

Table 8. The positive measures—PM, 1989 (EC-12).

Source: author. (*) The issue of “cabotage” was an issue among member-states.

![]()

Table 9. The 4 characteristics of the EU-15 Commission’s Maritime Strategy, 1996.

Source: author. (*) “Strategy” is surely an impressive term!

![]()

Graph 9. Towards a new maritime strategy, 1996-EU-15. Source: author; (*) footnote 53.

which was the new shipping industries, which emerged, particularly in “East Asia”54, competing EU-15 shipping!

8.1. A Common Policy for Competitiveness-CPC

The Commission thought that an increased competitiveness of EU-15 fleet will be achieved by (Graph 10).

The Commission, we believe, was un-prepared to tackle the start with the crew training issue, because it commissioned then a relevant study! The right step had better to establish first the connection of crew training to ship competitiveness... It has been taken for granted that a better trained crew will reduce ship’s costs! But how?

In our opinion Commission had also to investigate what part of the “crew

![]()

Graph 10. Ways to make EU-15 fleet competitive. Source: Commission’s strategy.

training cost” is paid by ships in national flags55. Commission lacked here a focus, and spent almost all its efforts to the problem56 of the Supply of EU-15 seamen, and especially of officers—an entirely different, but important issue57.

● The Research & development, we believe, is more important for shipbuilding and classification societies than for shipping, and for the steel manufacturers as well for the sea main engines designers!

● Also, valid is nowadays the research for a cheaper green oil... (Goulielmos, 2021d). Commission instead relied then on the 4th & 5th frameworks of the R&D program (1994-1998), the MARIS G-7 (in 1995), and on the ?.5m devoted for R&D in waterborne transport.

● But EU-15 shipping needed…a cheaper steel to start with, and thus lower building prices, to become competitive, on top of the new logistics in “short sea shipping” & ports, fast crafts, VTS, info. systems, simulations along with MAST58 etc., as proposed by Commission.

➢ As far as the State aid to shipping is concerned, article 92(1) defines it to be incompatible59 with the common market, though needed…despite article 92(3)(c)! In 1989, EC-12, Commission established guidelines60—revisable-to overcome this incompatibility! The State aid decided in 1996 was surely out of date, as tanker crisis, in 1974-1979, passed-away by 1996, and the dry cargo one, passed too away by the 2nd-half of 1987! State aid61 does not make ships competitive permanently, we believe.

➢ The cost of EC-15 fleets. The thorough knowledge of the cost of ships is imperative to draft a policy to make EC-15 fleets competitive! This knowledge is from inside shipping companies and few Professors-except late B. Metaxas-knew, as late R Goss told me.

➢ Roberts (1947) wrote an article on comparative shipping and shipbuilding costs and underlined: “a knowledge of the operating and capital costs of vessels of the main maritime countries is essential to an enlightened discussion of many aspects of shipping practice” (p. 296).

Commission attributed the higher cost of EU-15 fleet to:

● Employment-related charges (crew wages), and,

● Fiscal costs (taxation),

which Commission expected to be reduced by state aid. Commission mentioned in its 1989 guidelines the existence of flags of 3rd countries and flags of convenience. But there, too, Commission was un-prepared, and wanted to see first the costs of ships under the Portuguese and the Cypriot flag—the cheapest EC-12 flag and one flag from those of convenience!

8.2. ECSA62’s Commentary on Commission’s 1996 Strategy for a CMP

The ECSA’s views on CMP (Graph 11) were:

The association opposed63 to Commission’s competition policy in particular, characterizing it one-sided, misleading and unsubstantiated at parts! It is considered as a potential threat to EU’s liner sector, to diminish trade and to increase ships’ cost! The critique of the association was as follows (Graph 12).

As shown, ECSA’s commentary on Commissions’ maritime strategy underlined the importance of the industry, which brought-in $160b of earnings in 1995, gained worldwide. Also, it reminded the Commission that seaborne trade will double by 2010. As expected, ECSA argued that the liner conference system provided regular and reliable services etc., which was true. The owners of container ships spent $65b since 1973 and transported 30m TEUs in 1995. Finally, it accepted reg. 4056. But ECSA strongly reacted against EU-15 competition policy!

![]()

Graph 11. ECSA’s commentary on “a new maritime strategy” EU-15. Source: author; inspired by ECSA’s commentary. (*) Shipowners insist that all actions concerning Shipping to be taken in IMO and ILO; they are strongly against regional measures.

![]()

Graph 12. Suggestions of ECSA as a result of Commissions’ COM for a “shipping strategy”, 1996, (EU-15). Source: author; inspired by ECSA’s commentary, 1996. (*) In 1992 commission created the “Maritime Industries Forum”-MIF, which brought together parties from all segments of maritime industry & administrations to discuss maritime problems. In our opinion, a forum consisting only of Ports, Shipbuilding & Shipping, it would be righter. In fact, Commission, we believe, inclined towards the “Marine Industries”, which emerged 10 years later, in 2006 (ISBN 92-79-01825-6) (Picture 1)! MIF (in 2000) covered also fisheries, maritime equipment, energy, marine resources, environmental protection (oil, gas, potable water, aquaculture & minerals)!

9. Part VI: The Future Common Marine Policy-EU-28 (1998-2021)

In our 2nd paper, we will present the remaining period (1998-2021) for a CSP/ CMP. Also, a Common Marine policy (Picture 1) emerged in 2006.

As shown, Marine Industries, and their economics, are the broader circle including both shipping and maritime industries and their economics. These… discovered by EU-25 with a great joy, and publicity, in 2006. The joy was great because EU-25, at that time, did not copy UN or IMO, as did in the past, but designed its own “Common Marine Policy” independently, which was holistic and more general than both CSP and CMP! Surely, the focus required has been lost…

![]()

Picture 1. The Maritime cluster of the Netherlands, consisted of 10 industries. Source: Lloyd’s list, June 1999.

10. Part VII: “Fit for 55”

International shipping industry has to reduce its carbon intensity per ton/mile, by at least 40%, by 2030, and to try the 70% mark by 2050, vis-à-vis 2008. The total annual GHG emissions have to be reduced by at least 50% by 2050, vis-à-vis 2008 (according to Paris agreement).

IMO also adopted a strategy for decarbonization, in April 2018. Shipping industry considers the EU-27 “Green Deal” and “fir for 55” package ambitious. As a result, shipping industry proposed to IMO to set-up a research and development board (IMRB/IMRF), and fund, supplying it by a mandatory contribution from each vessel > 5000 GT per ton of fuel consumed. The scope is to expedite the development of an alternative fuel(s) required by shipping industry.

The EU-27 proposed a “Well-to-Wake” (WtW) certification to be developed and validated by IMO, in Sept. 2021. IMO adopted, in 10-17 June 2021, a comprehensive package of legally binding technical and operational short-term measures. Their scope is to reduce CO2 emissions from ships (in force since 01/11/2022) (MEPC 76)).

The industry relies on technology and on carbon-neutral fuels. Also on innovation investment, on building the required infrastructure etc. (Goulielmos, 2021d). The views of shipping industry seem to coincide with those of Goulielmos (2021d) on the theory of “increasing returns to scale”!

The “fit for 55” is based on 2 foundations (Graph 13).

![]()

Graph 13. The EU-27 “fir for 55” policy package. Source: author.

EU-27 considered the extension of the EU-ETS to maritime industry from 2023—phasing out also existing allowances—for vessels > 5000 GT; 100% implementation to intra-EU voyages & 50% to extra EU ones, within the MRV64 task. The 2nd regulation proposed the reduction of the GHG intensity of energy used by vessels by 6%, 26% and 75% by 2030, 2040 & 2050 vis-à-vis 2020 in line with MRV.

The “RED” (renewable energy directive) set fuel sub-targets (biofuels & hydrogen from renewable electricity). This looks also at the supply of electricity to ships in ports by 2030. The “AFID”—“alternative fuel infrastructure directive”— needs the development of onshore power supply in EU-27 ports by 2030 and LNG supply by 2025.

However, the international maritime community disappointed by the inertia shown by the participating governmental leaders in COP26 (Oct. 2021), where the carbon emissions from ships were further reduced from 40% it was. Moreover, the ICS (international chamber of shipping) stated that during MEPC 77 of IMO (November 2021) no real progress made! The WSC (world shipping council) underlined the hopeful sign that an increased number of states supported the establishment of a R&D fund, for making the future technologies to contribute to ships’ decarbonization!

Worth-noting is that “Maersk-shipping company” argued that the environmental impact of shipping must be reduced by adopting: 1) a global fuel standard; 2) a time limit in building ships using fossil fuels; 3) a creation of a global fund; 4) one GHG price, so that to pass to alternative fuels; 5) a creation of green sea routes; and 6) re-enforcing the system of data-collection of IMO, and its transparency. The whole above issue was supported by: BIMCO, Intertanko (owners of tankers), Intercargo (owners of dry cargo ships), WSC, etc., already since 2019 (in MEPC 75), but the whole issue passed-on…to the forthcoming MEPC 78 (2022)!

The views of the greater part of international shipping industry over the possible ways to reduce GHG emissions from ships, as a reaction to EU-27 initiative named “fit for 55” package, is to increase the existing 40% target to 55% by 2030!

Moreover, we hoped that the COP26 would be more courageous, than it was, despite the steps to decarbonize international shipping taken already. Governments, however, failed to translate words into actions! In addition, IMO MERC 77 failed to revise current GHG targets for 2030, as mentioned.

Given that the author had the purpose to write an additional paper covering the period between 1998 and 2021, the reader has rather to wait to have a complete historical picture of the total shipping, maritime and marine policy of the EU-27/28.

This paper showed the mistakes committed by Europeans in forming EU, which may be used as a guide for future economic unions. The equalization of wages and salaries, which was a target, announced, but never achieved. This needs further research. Moreover, and more important, the “national interest” instead of leaving it outside the door of EU, all nations brought it-in with them in all shipping, maritime and marine issues! This needs further research. The targets of French Revolution-equality, liberty, fraternity, remained unfulfilled…as liberty from energy needs has a long way ahead and a climate which will not kill its European citizens is also sought-after. This also needs further research.

11. Conclusion

The port interests of EC-6, we believe, excluded, originally, “sea transport” from EC-1957-Treaty, and from a “common Maritime Policy”. So, a CSP/CMP delayed 28 years, till CM undertook by UK, in 1985, with contributions from Greek transport commissioners. UK was an island country, with a long past ship-owning, port and shipbuilding experience.

EU-6 shipping policy, by the influence of transport commissioners Anastasopoulos and Petropoulos, centered, initially, round the state-members that were “cross-traders”, like Greece. Thus, EU followed all along the principle of “laissez-faire”, but with 2 exceptions: the “tramp shipping pools” and the “liner shipping conferences”!

For safety, an EU-10 common shipping policy was easy, as it copied already the maritime nations acting through IMO, with a 4 - 5 years delay! Moreover, a policy for liners was also easy, at that time, in 1976, copying United Nations’ Code of Conduct.

But in 1996, Commission’s communication caused the reaction of ECSA—or really the shipowners of UK, Germany and Denmark… In addition, Italy—most probably—“asked” the “waiving of Cabotage privilege” inside EU-12, and caused the reaction of Greece (1989).

The EU-15 was proud, despite its long delay, for it succeeded—as alleged—in opening-up the European markets, in particular, through its CMP, and gave consumers a wide choice of shipping services, meaning most probably liners. It applied the EC-15 competition rules to all markets… But it admitted that failed to increase either EC-15 seafarers’ employment or to avoid flagging-out65 towards a large number of parallel registries! This flagging-out indeed diminished the competition against EU-15 fleet except on costs needed for safety.

In fact, the EU-28 shipowners tried to protect themselves from the competition of non-EU ships and flags, by establishing the parallel registries, where crew costs were lower as well taxation, except for the safety standards. Thus, they could compete their competitors. To this surely decisively contributed the 1974- 1979-1987 shipping crisis!

Today, EU-27 is threatened by a wave of immigrants, amounted in 2018 up to 22m, and increasing after the pause of Afghanistan war; also, by the lack of adequate own energy; and by Russia and its supply of natural gas.

But more serious than the above, EU-27 is threatened by the possibility to fail in decarbonizing EU-27 shipping, and planet, by 2030, and thus no one to be “fit for 55”, or even for 40, as COP26 and MEPC 77 paid no particular attention to the problem. Will EU-27, be still 27, when the problem of climate will crop-up again more urgent and intense? We doubt.

EU-12-15 wanted to make its fleet more competitive, but it did not catch the last train, which was the building cost, covering 50% of total cost! The flag costs of each member-state also ignored, but these were responsible for flagging-out, together with crew cost and taxation.

Poor countries with large shipping are unable to provide any state aid. And rich shipowners benefit their poor countries of birth, no matter if their ships used to fly foreign flags (Onassis; Niarchos and others).

Shipping-the unknown…is the chicken making the golden eggs-needing a simple holistic treatment so that not to kill it. This means to help it to maintain the lowest possible total cost, starting from the building one.

NOTES

1The EC-6 made-up by the ECSC (1952) (Coal & Steel Union) & the Atomic Energy Union (EURATOM; 1957). A foundation treaty signed in 13/03/1951 (forerunner of EC), which ratified in 1952 by EC-6. Four further European treaties followed: Maastricht (1992), Amsterdam (1997), Nice (2001) & Lisbon (2007)…and Brexit (2020).

2During the “Great War”, 40m died (also from Spanish flu) (1914-1918). During 2nd WW, 75 million died, where 23.5m from famine & diseases (internet). The idea of the EC was to avoid a 3rd global war and to rebuild Europe. The original member-states selected on their similar stages of development. Certain European countries endowed with rich deposits of coal and iron-ore (the SAAR area was one of quarrel between W Germany and France).

3In W. Germany fascism prevailed; also, the theory that the “Aryan race” is superior & must lead.

4Italy served fascism too; an ally of Germany. The Greek-Italian war left about 27,000 dead.

5Greece resisted Germany & Italy in 1940, as well Bulgaria, etc. Greece established the democracy. Also, the constitutional monarchy (the “Kingdom of Greece” established in 1833-till 1862) lasted till end-1967. In 1973 Greece adopted Presidential Democracy.

6A religion asking people to “love…one’s enemy”, apart from being the only true. Orthodoxy e.g., does not recognize the saints nominated by Catholics, after the separation (‘‘schema’’) of Churches (16/07/1054).

7Some wise people believe that adopting “Orthodox Christianity”, is the only way to form one global Church. Others believe—and work—for one “good” religion striking-out devil, hell, and…forgetting death! A heresy!

8Established by Maastricht T as supplementary of the national one (EP number 137c & d).

9Patriotic actions, feelings, principles and efforts, gaining priority over…solidarity!

10 Spartiotis (1980) argued that 3 reasons prevailed in forming EC: (a) not to isolate W. Germany; (b) a large common market needed for economic development; (c) to terminate the practice, in 1950, where all countries used to put tariffs & exercise protectionism due to the 1929-1933+ economic crisis. Ø The French Minister of foreign affairs Robert Schuman, in 09/05/1950 (right photo) (a spiritual child of Jean Monnet—left photo), declared the “French-German Union of Coal & steel” (source: EU official website).

11His opinion has a weight for his position & rank.

12E.g., university education lasts in EU-27, 3 years, while Greece has 4, and 5 in technical universities. Greece should modify the duration of university studies to 3 years, we believe.

13EU can have about 45m soldiers, out of about 446m people (2020).

14Articles 85-94 relate to competition, and are implemented for the economy in general…but also for shipping as the case may be!

15Supposed to be an electronic list of jobs required, in various EU nations, every morning, that could be consulted by European persons seeking a job. We must admit that, in central Europe, transportation became indeed faster.

16Goods loaded/unloaded.

17The EU-27 shipbuilding employed: in Poland (22%), in Spain & Italy (16.5%), in Denmark, France, & Germany (28%), plus in Netherlands and Finland (33.5%), a total of 52,700 jobs, while only S Korea and Japan had about 53,000 in 2005.

18Tax is calculated and paid on the GRT/NRT etc. of every vessel according to size and age. Adopted first by Greece.

19Japanese government sponsored its shipbuilding program as early as 1947; in 1955 the 1st export ship boom started; in 1963 the 2nd and in 1965 the 3rd. In 1973 Japan received almost 34m GT of newbuilding orders-the highest ever on the breaking-out of the 1st oil crisis. In 1980 the superfluous shipbuilding facilities disposed, on average, by 35%, something continuing in 1983 and 1984. The Japanese shipbuilding employed 247,000 persons in 1978 and 209,000 in 1984, and falling.

20 Gardner & Pettit (1999a, 1999b).

21The EMSA-European Maritime Safety Agency (in 2002) (Lisbon) reported for 2019: UK had ~30,000; Greece ~22,000; Poland ~21,000; Norway ~19,000 (=92,000). 3.5% of the 193,235 were hopefully under 25 years of age (18-) & in 60+ were 31,000 (16%).

2298% were males; average age 44 years (excluding Poland).

23This is most helpful because masters & officers normally (e.g., in Greece) become shipowners by 33%.

24The above amount is an underestimation as Greece imports now about ?0b in US$.

25Greeks were in favor of the flags of convenience since the time of the late Onassis and Niarchos, as providing freedom of action (Goulielmos, 2021b, 2021c).

26In 1976, a Commission communication to the Council dealt with the relations of EC-9 with 3rd countries on shipping matters (e.g., USA & Japan). This purposed to stimulate a debate for a CSP. A consultation procedure adopted. As a rule, Commission gathered information before taking action, and this delayed matters further (77/587 (17/Sept.)).

27This concerned the activities of certain 3rd countries in cargo sharing, based on article 84(2), and on collecting prior information (effective 1989). This concerned certain members of the Comecon states (USSR, GDR & Poland), in late 1970s, which gained cargoes by offering lower freight rates, (as much as 50%), vis-à-vis EU-fleet. This indeed was a serious problem, because Soviet ships did not pay insurance or financial costs, they bought bunkers at low prices at East European ports and certain persons from crews were fulfilling their military service on board (doc. 479/76) (78/774 (21/09/1978)) and Council’s directives 79/115 (08/02/1979) and 116.

28CM on Pilotage.

29Greece applied to access EC in 1959; its application accepted in 1961 (09/07). It accessed to EC in 1961-1962, signing the Athens convention. It had a grace period of…22 years to boost its exports. The period of dictatorship, 1967-1974, stalled the procedure, which re-started in 1974. In 1975 Greece asked for a full accession and an agreement signed in 1979 (May) for accession in 1981!

30COM (76)314 final/1976.

31EP, WD 10/1972 (& Maritime Policy & Management, 1976, 4, 55-60, “commentary on European Community ports policy”).

32Doc. 479.

33Discussion on “UN Code of Conduct” is omitted (end-1976) for concerning liners.

34COM (85)90 final.

35P 95/1984 (Dec.) (COM (84) 668 final): a “Progress towards a CMP” (to the CM)—“a set of proposals”.

36CM’s decisions, recommendations and resolutions bridged the gap created by article 84, when various issues of maritime shipping emerged during 1977-1984.

37A French term meaning that trade & passengers moving along the coasts of one country, should be served by ships flowing coastal nation’s flag; a license required issued by the coastal Government.

38Maritime economists distinguish sea transport in 2 sectors: one helping economies to grow and this is liner shipping transporting products of manufacturing and craft industry, and one helping industries with raw materials etc. (iron-ore, coal, oil, fertilizers, grain etc.) (served by tankers & bulk carriers).

39EU expected to adopt the “UN Code of Conduct for Liners” (in 1979) (R 954).

40As mentioned elsewhere the marginal carrier (higher average cost) will determine the level of the freight rate payable. The 7 major oil companies in the past conceived better than Commission the way how to reduce transport costs by boosting the supply of tankers…by promoting/inducing shipbuilding orders.

41Articles 92 & 93 of the EC-6-T.

42TRA, par. 2.2.

43“A future for the community’s shipping industry: measures to improve its operating conditions”.

44COM (89) 266 final (03/08/89).

45Article 4 of the COM (91) 54 in 19/03/1991. In 1996 (EU-15) the Commission declared that it will withdraw its proposal for a Council regulation establishing a community ship register (Euros) of 1989/1991. Also, the proposal for a regulation on a common definition of a community shipowner of 1989/1991, withdrew, except: with 4057 reg., unfair pricing and state aid.

46We refer indirectly to shipowners’ benevolent funds and investments in their country of birth beyond employment, taxation and foreign currency imported etc.

47OPEC (in 1960) as being a “Cartel of governments” met no sanctions! This had to be changed; and the same has to be done with all cases of dominant positions of governments like that of Russia in the case of natural gas.

48This is the legal advisor of the Hellenic Government in matters of maritime transport.

49We can imagine to be Italy.

50Major shipping regions in Far East, among 23, were: Russia, Japan, China, S Korea, Hong Kong (China), Singapore & Chinese Taipei.

51Greeks had the biter experience of the intervention of the then Prime Minister El. Venizelos, who asked them to buy ships within 4 - 7 years so that to get their money back from the war insurance compensations held by the government. Venizelos believed that Greeks, after the 1st WW, will stop investing in ships, and he wanted to induce them this way. Greeks bought ships at £300,000 each in 1918, and very soon their values fell down to £5000 each!

52Res. 97/C 109/01) (24/03/1997).

53“Shaping Europe’s Maritime future”—“a contribution to the competitiveness of Europe’s maritime industries”—COM (96) 84, 13/03/1996.

54Mainly: Japan, China, S. Korea & Chinese Taipei.

55Shipowners in Greece pay the greater part of seamen’s education. The state had to provide free of cost education for seamen including books and expensive teaching equipment and retraining of nautical teachers.

56MCO-ISF monitor the shipping manpower from time to time and issue updates. It is well known that officers are in great need and there all efforts must be concentrated. More so that officers are quasi-future shipowners, at least for Greeks! Commission set up a Joint committee on Maritime transport (in 1987).

57We agree with the proposals contained in communication’s part B (pp. 24-26).

58COM 95 (688) final 20/12/95.

59As distorting competition.

60(SEC (89) 921 final)).

61National state aid was related: to tonnage tax, exemption/reductions in corporate & seafarers’ income taxes, social security liabilities, generous accounting provisions to reduce taxation etc.

62European Community shipowners’ associations (1965), consisting of EU-19 plus Norway (former CAACE).

63We may identify Germany behind this, as being a prime owner of liner ships, followed by UK and Denmark (=28% share for EU-7 in dwt in 1994).

64On 04/02/2019 Commission proposed the amendment of the regulation 2015/757 on the monitoring, reporting and verification of the CO2 emissions from ships.

65The Commission noted-down certain parallel registries in EU-15: Denmark-DIS needing only a national Captain; no tax income by seafarers; Finland (1992) doubled its fleet in the parallel registry; Germany ISR (1989) stabilized its tonnage; Sweden applied tax rebates & social security charges. France—in Kerguelen islands initially established it; Portugal formed the MAR (Madeira) registry; Spain in Canary Islands; the Netherland in Antilles, administered autonomously; UK used the registers of various crown and dependent territories, flying the red ensign. Italy was also thinking of a parallel register.