Properties of Lorenz Curves for Transformed Income Distributions ()

1. Introduction

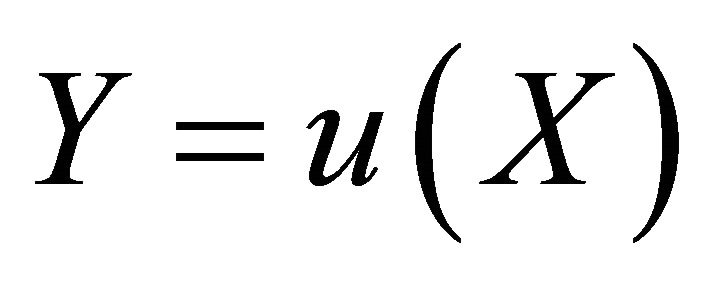

Redistributions of income according to tax or transfer policies can be considered as variable transformations of the initial income. The transformation is usually assumed to be positive, monotone-increasing and continuous. The initial results are given in Theorem 1. [1-3] Consider a nonnegative random variable X with the distribution function , mean

, mean  and Lorenz curve

and Lorenz curve . Let

. Let  be a continuous monotone increasing function and assume that

be a continuous monotone increasing function and assume that  exists. Then Lorenz curve

exists. Then Lorenz curve  for

for  exists and 1)

exists and 1)  if

if  is monotone decreasing2)

is monotone decreasing2)  if

if  is constant and 3)

is constant and 3)  if

if  is monotone increasing.

is monotone increasing.

The importance of case (1) is that it gives the inequality effect of progressive taxation. The case (2) corresponds to flat taxes. The last case (3) is of minor economic importance, but it is included in order to complete the theorem. Recently, Fellman [4,5] has also discussed discontinuous transformations. If the transformation is considered as a tax or a transfer policy, the transformed variable is either the post-tax or the post-transfer income. Under the assumption that Theorem 1 should hold for all income distributions, the conditions are both necessary and sufficient [2,4]. Hemming and Keen [6] have given an alternative version of the conditions. In this study we consider other general properties of the transformed Lorenz curves.

2. Background

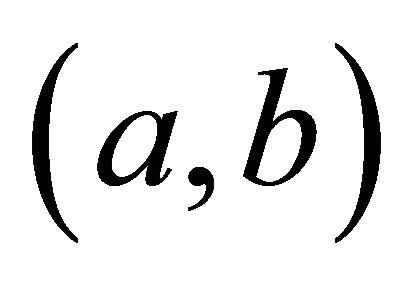

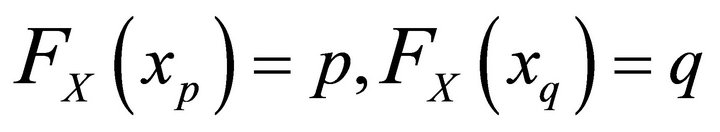

Consider income X, defined on the interval , where

, where , with the distribution function

, with the distribution function , density function

, density function , mean

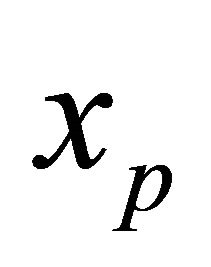

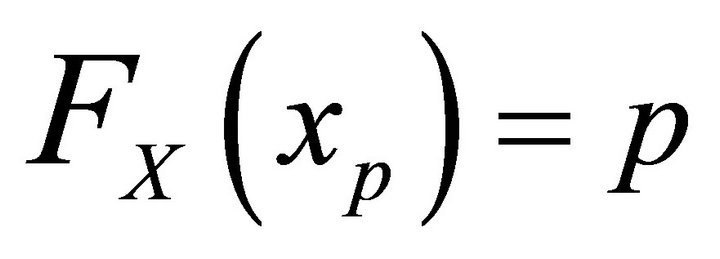

, mean , percentile

, percentile  defined as

defined as  and Lorenz curve

and Lorenz curve . The general formulae are

. The general formulae are

(1)

(1)

and

(2)

(2)

where .

.

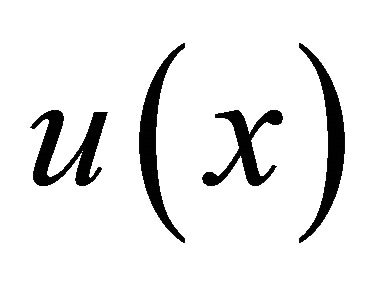

We consider the transformation , where

, where  is non-negative, continuous and monotone-increasing. Since the transformation can be considered as a tax

is non-negative, continuous and monotone-increasing. Since the transformation can be considered as a tax  or a transfer policy

or a transfer policy , the transformed variable is either the post-tax or the posttransfer income.

, the transformed variable is either the post-tax or the posttransfer income.

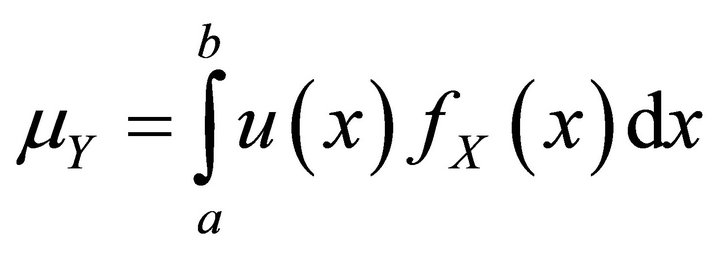

The mean and the Lorenz curve for variable Y are

(3)

(3)

and

(4)

(4)

A fundamental theorem concerning Lorenz dominance is [2,4].

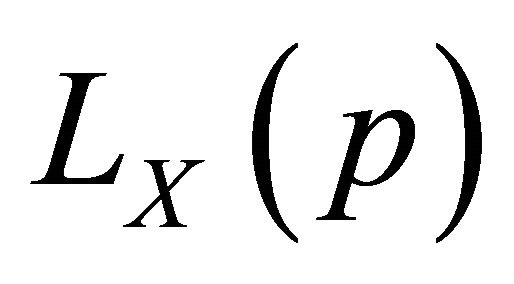

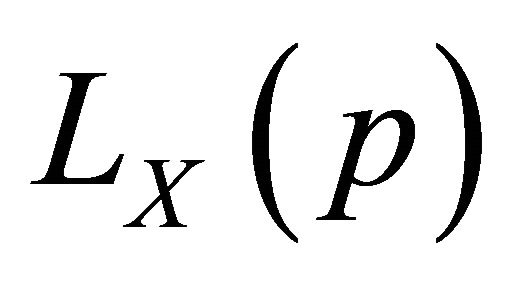

Theorem 2. Let  be an arbitrary, non-negative, random variable with the distribution

be an arbitrary, non-negative, random variable with the distribution , mean

, mean  and Lorenz curve

and Lorenz curve . Let

. Let  be a nonnegative, monotone-increasing function, let

be a nonnegative, monotone-increasing function, let  and let

and let  exist. The Lorenz curve

exist. The Lorenz curve  of Y exists and the following results hold:

of Y exists and the following results hold:

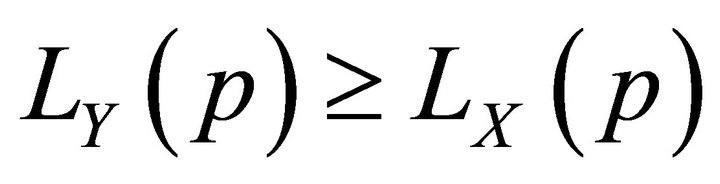

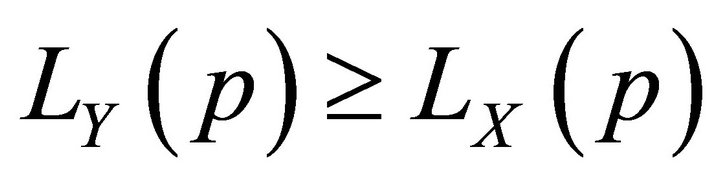

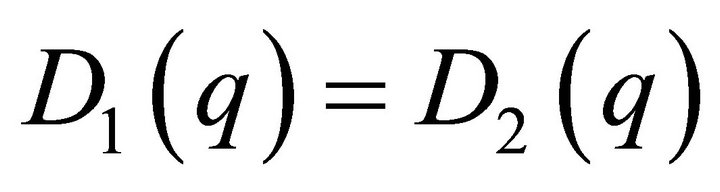

1)  if and only if

if and only if  is monotone-decreasing

is monotone-decreasing

2)  if and only if

if and only if  is constant and

is constant and

3)  if and only if

if and only if  is monotone-increasing.

is monotone-increasing.

In the following, we consider additional properties of the Lorenz curve . If

. If

is constant, then according to Theorem 1 (2),  and the transformed Lorenz curve is identical with the initial one, a case which will be ignored.

and the transformed Lorenz curve is identical with the initial one, a case which will be ignored.

3. Results

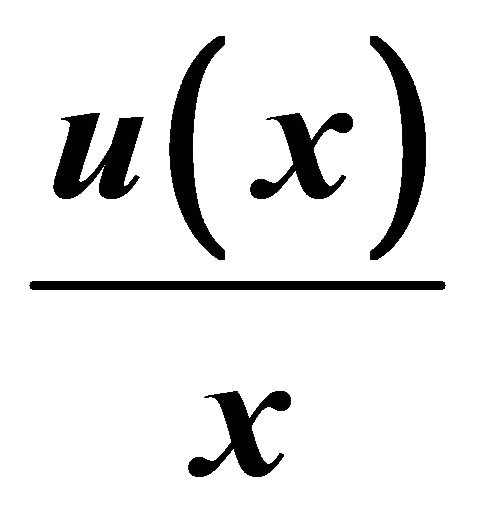

3.1. The Ratio  Is Monotonically Decreasing

Is Monotonically Decreasing

According to Theorem 1  Lorenz dominates

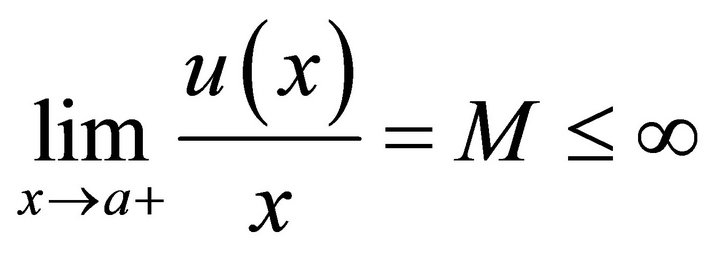

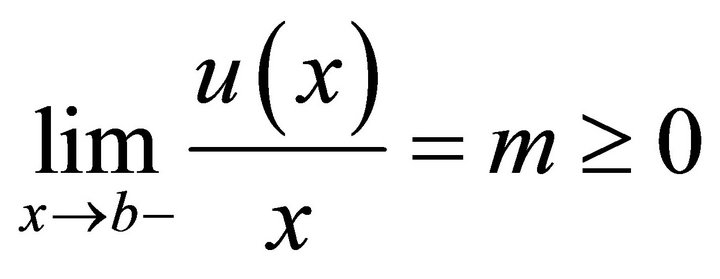

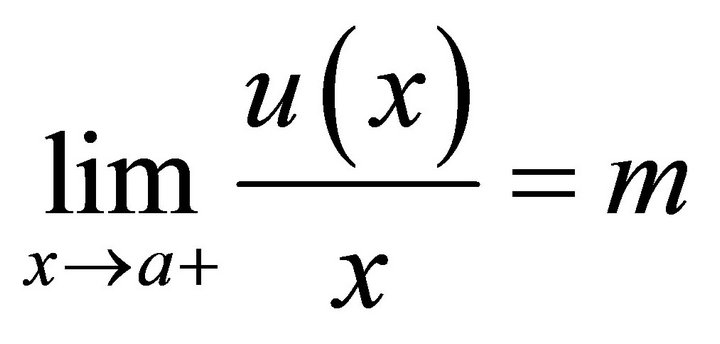

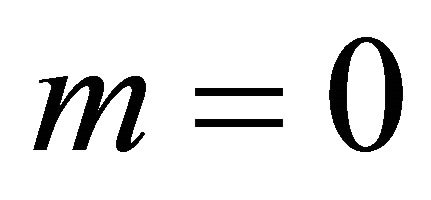

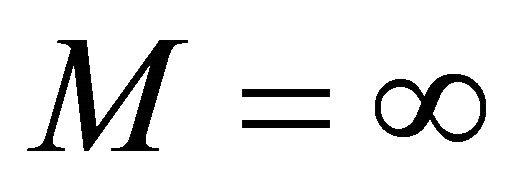

Lorenz dominates . We introduce the values M and m such that

. We introduce the values M and m such that

and

.

.

Consequently,

.

.

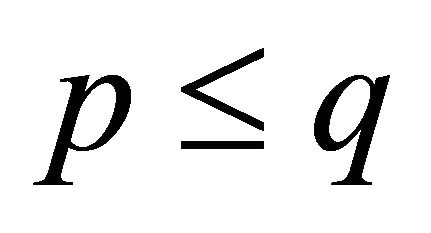

Let ,

, . Assume that

. Assume that  and that

and that  and consequently,

and consequently,

.

.

Note that points  and

and  are chosen arbitrarily and that the equality signs cannot be ignored because we also include the functions

are chosen arbitrarily and that the equality signs cannot be ignored because we also include the functions

which are not uniformly strict decreasing in the class of transformations. Hence, we have to include members for which equalities hold for almost the whole range and, in addition, sub-intervals in which strict inequalities hold can be chosen arbitrarily short and located arbitrarily within the range

which are not uniformly strict decreasing in the class of transformations. Hence, we have to include members for which equalities hold for almost the whole range and, in addition, sub-intervals in which strict inequalities hold can be chosen arbitrarily short and located arbitrarily within the range . If one pursues general conditions, the inequalities (8) and (9) obtained below cannot be improved. If we assume that

. If one pursues general conditions, the inequalities (8) and (9) obtained below cannot be improved. If we assume that

is monotonically decreasing, then  must be continuous, otherwise

must be continuous, otherwise

should have positive jumps [1].

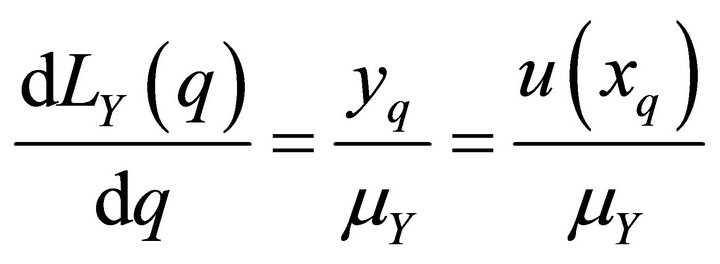

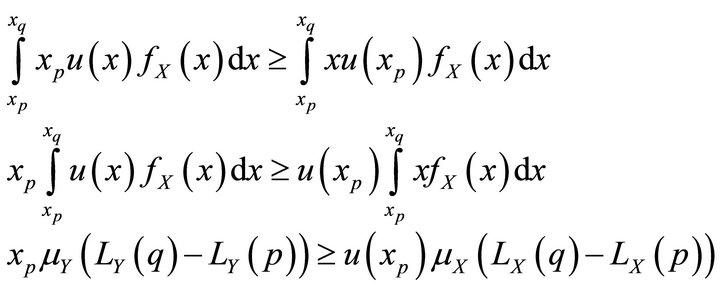

From

it follows that . The integration over the interval

. The integration over the interval  yields

yields

(5)

(5)

and

.

.

Analogously, it follows from

that , and we obtain

, and we obtain

. (6)

. (6)

Consequently,

. (7)

. (7)

When  in (7), then

in (7), then

and one obtains

. (8)

. (8)

The lower bound gives an evaluation of how much the Lorenz curve has increased. The upper bound is of minor interest and is commented on later.

When  in (7), then

in (7), then

and one obtains

.

.

In order to compare these inequalities with the inequalities in (8), we change the argument from p to q, and the inequalities are

(9)

(9)

The lower bound gives an evaluation of how much the Lorenz curve has increased. The upper bound is of minor interest and is discussed later.

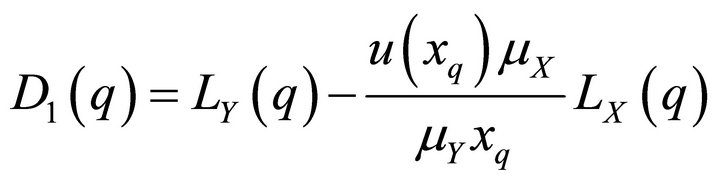

Inequality (8) is applicable to small values and inequality (9) to large values of q. For small values of q, we consider the difference

(10)

(10)

and for large q we consider the difference

. (11)

. (11)

In general,

and

.

.

The ratio

is decreasing and consequently

.

.

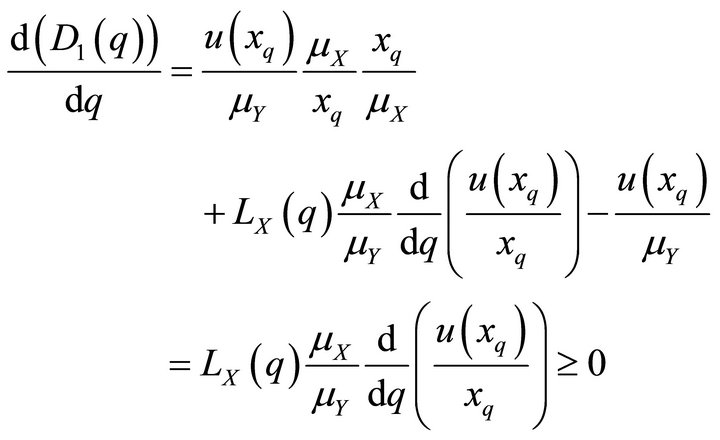

Now we differentiate  and obtain

and obtain

Consequently  is increasing from zero at

is increasing from zero at  to a maximum

to a maximum  for

for  (say).

(say).

Now we differentiate  and obtain

and obtain

Consequently  is decreasing from

is decreasing from  to zero when

to zero when . The point

. The point , at which the shift from (10) to (11) is performed, is chosen so that

, at which the shift from (10) to (11) is performed, is chosen so that . Now,

. Now,

;

;

that is,

.

.

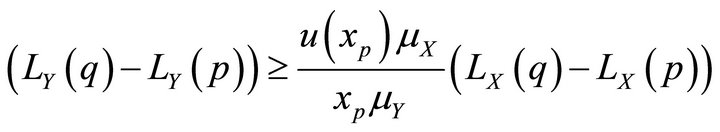

Consequently,

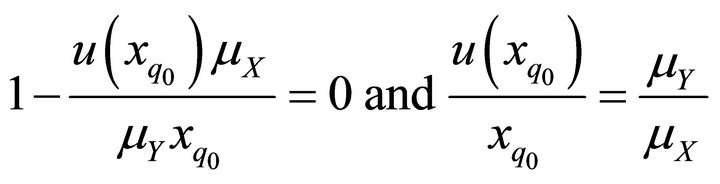

Since the ratio

is decreasing, the difference

shifts its sign from plus to minus at point . Hemming and Keen ([6]) gave the condition for Lorenz dominance that

. Hemming and Keen ([6]) gave the condition for Lorenz dominance that

crosses the

level once from above. Our results above have shown that the crossing point is . The condition obtained can also be otherwise explained. If we write it as

. The condition obtained can also be otherwise explained. If we write it as

we obtain the formula

we obtain the formula

that is, the Lorenz curves

that is, the Lorenz curves  and

and  have parallel tangents and the distance

have parallel tangents and the distance  between the Lorenz curves is maximal for

between the Lorenz curves is maximal for .

.

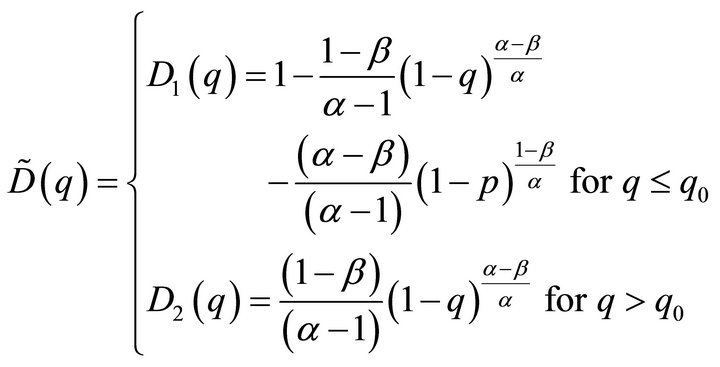

We define the difference function as

, (12)

, (12)

and the lower bound of  is

is

. (13)

. (13)

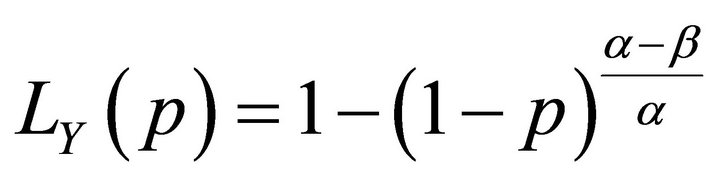

Figure 1 shows the Lorenz curves ,

,  , the lower bound

, the lower bound  and the difference

and the difference  between

between  and the lower bound

and the lower bound .

.

Remarks. The variable Y Lorenz dominates X, and the upper bounds in (8) and (9) tells us nothing about the reductions in the inequality. The upper bound contains the maximum value  and one has to take it for granted that it is also inaccurate when M is finite. In addition, there may be situations in which

and one has to take it for granted that it is also inaccurate when M is finite. In addition, there may be situations in which . The minimum value m can be zero, and in this case the upper bound is one and the obvious inequality

. The minimum value m can be zero, and in this case the upper bound is one and the obvious inequality  is obtained.

is obtained.

3.2. The Ratio  Is Monotonically Increasing

Is Monotonically Increasing

The analysis of this case follows similar traces to the earlier study and the results are analogous to our earlier results, but in this case  may be discontinuous. Only the inequality signs have changed their directions. We introduce the values

may be discontinuous. Only the inequality signs have changed their directions. We introduce the values and

and  such that

such that

and

and

and consequently

.

.

Note, that in this case the points  and

and  are also chosen arbitrarily and that the equality signs cannot be ignored because we also include functions

are also chosen arbitrarily and that the equality signs cannot be ignored because we also include functions

which are not uniformly strictly increasing in the class of transformations. Hence, we have to include members for which equalities hold for almost the whole range and, in addition, the subintervals where strict inequalities hold can be arbitrarily short and can be located arbitrarily within the range. If one pursues general conditions, the inequalities (17) and (18) obtained below cannot be improved.

If  is discontinuous, the discontinuities can only

is discontinuous, the discontinuities can only

be a countable number of finite positive jumps. Under such circumstances  is still integrable.

is still integrable.

We use the same notations as above and assume that , that

, that  and consequently that

and consequently that .

.

Now,

.

.

Consider . The integration over the interval

. The integration over the interval  yields

yields

(14)

(14)

and

.

.

Analogously, if we consider  we obtain

we obtain

(15)

(15)

and

.

.

Hence,

. (16)

. (16)

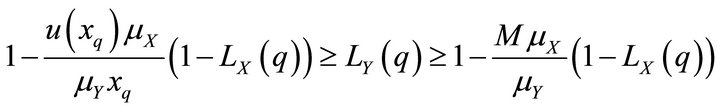

When  in (16), then

in (16), then

and one obtains

. (17)

. (17)

Now, the initial variable X Lorenz dominates the transformed Y and the upper bound is the interesting case.

When  in (16), then

in (16), then

one obtains

After a shift from p to q, we obtain

(18)

(18)

Now the upper bound is of interest. Formula (17) is applicable for small values and formula (16) for large values of q. In the following, we consider the difference between the upper bound and the Lorenz curve , that is, for small values of q

, that is, for small values of q

. (19)

. (19)

For large values of q, we consider the difference

. (20)

. (20)

In general,

.

.

The ratio

is increasing and consequently,

.

.

Now we differentiate  and note that

and note that

is increasing and obtain

.

.

Consequently  is increasing from zero to a maximum for

is increasing from zero to a maximum for .

.

Now we differentiate  and obtain

and obtain

.

.

Consequently  is decreasing from a maximum to zero. The point denoted

is decreasing from a maximum to zero. The point denoted , at which the shift from

, at which the shift from  to

to  is performed, satisfies

is performed, satisfies  .

.

Now,

that is,

that is,

.

.

This condition is identical with the condition, given above, in which

is decreasing.

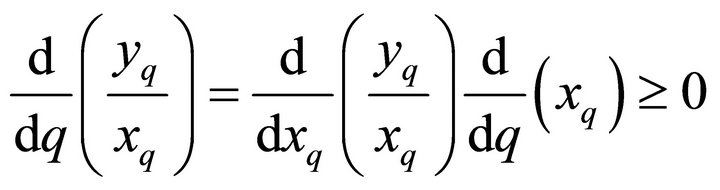

Again, the condition

can be written

and we obtain the formula

that is, the Lorenz curves

that is, the Lorenz curves  and

and  have parallel tangents and the distance between the Lorenz curves is maximal.

have parallel tangents and the distance between the Lorenz curves is maximal.

We define the difference function as

, (21)

, (21)

and the upper bound of  is

is

(22)

(22)

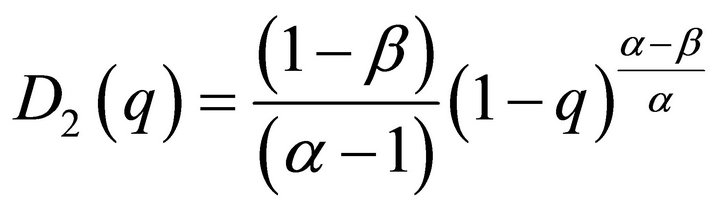

In Figure 2, we sketch the Lorenz curves ,

,  , the upper bound

, the upper bound  and the difference

and the difference  between the upper bound

between the upper bound  and

and .

.

Now the lower bounds are of minor interest because the initial variable X Lorenz dominates Y. Note that  is possible in some situations and the lower bound in (17) can be zero. Note that M can be great and even

is possible in some situations and the lower bound in (17) can be zero. Note that M can be great and even  is possible in some situations and the lower bound in (18) can be even negative.

is possible in some situations and the lower bound in (18) can be even negative.

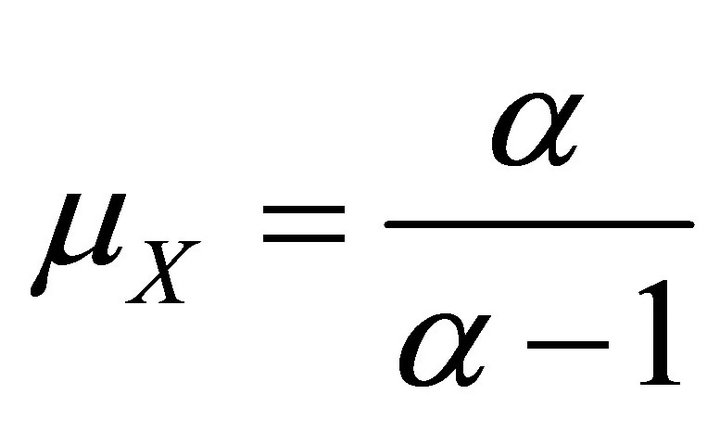

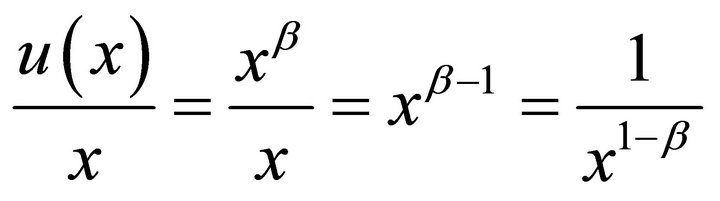

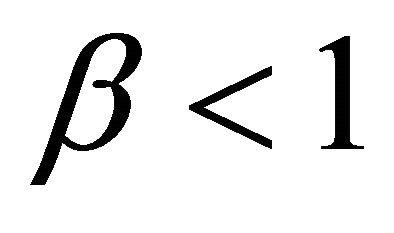

Example 1. The Pareto distribution. Consider income X with the Pareto distribution  and

and , where

, where  and

and . Now,

. Now,

and the Lorenz curve

.

.

From  we obtain

we obtain . Let the transformation be

. Let the transformation be  so that the function

so that the function  is decreasing. We obtain

is decreasing. We obtain , the Lorenz curve

, the Lorenz curve

,

,

and

and

For , the ratio

, the ratio

is decreasing, this case being sketched in Figure 1, and if  the ratio

the ratio

is increasing, this case being sketched in Figure 2.

4. Conclusion

Redistributions of income have commonly been defined as variable transformations of the initial income variable. The transformations are mainly considered as tax or transfer policies yielding post-tax or post-transfer incomes and therefore, the transformations are usually assumed to be positive, monotone-increasing and continuous. Recently, discontinuous transformations have also been discussed. The fundamental concern has been the Lorenz ordering between the initial and the transformed income. In this study we constructed limits for he transformed Lorenz curves. We considered the optimal cases that the transformed variable Lorenz dominates the initial one and the initial variable Lorenz dominates the transformed one. In applications, the first case is more important than the second, because it yields policies which reduce the inequality. The case (2) in Theorem 2 is not included in this study because the initial and the transformed Lorenz curves are identical. The limits obtained hold generally for all distributions and a broad class of transformations. If one pursues general conditions the inequalities obtained cannot be improved.

5. Acknowledgements

We are grateful to an anonymous referee for comments and suggestions on a previous version of the manuscript. This study was in part supported by a grant from the “Magnus Ehrnrooths Stiftelse” Foundation.