Psychology 2013. Vol.4, No.12, 950-955 Published Online December 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/psych) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/psych.2013.412137 Open Access 950 Competitive Orientations and Men’s Acceptance of Cosmetic Surgery Bill Thornton1, Richard M. Ryckman2, Joel A. Gold2 1Department of Psychology, University of Southern Maine, Portland, USA 2Department of Psychology, University of Maine, Orono, USA Email: thornton@usm.maine.edu Received September 26th, 2013; revised October 27th, 2013; accepted November 25th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Bill Thornton et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. In accordance of the Creative Commons Attribution License all Copyrights © 2013 are reserved for SCIRP and the owner of the intellectual property Bill Thornton et al. All Copyright © 2013 are guarded by law and by SCIRP as a guardian. As with women, men are experiencing increased pressure to achieve media-conveyed societal ideals for appearance and their consideration of cosmetic surgery as a means to enhance their appearance for com- petitive advantage in social and career realms has been increasing. This study considered individual dif- ferences in competitive orientations and the acceptance of cosmetic surgery among men. Hypercompeti- tiveness (psychologically unhealthy) was predictive of acceptance of cosmetic surgery even after age, self-esteem, body mass index, and body dysmorphia were taken into account. Personal development competitiveness (psychologically healthy) was negatively associated with body dysmorphia and was not predictive of acceptance of cosmetic surgery among men. These results for men, along with previous re- search among women (Thornton et al., 2013), indicate that a hypercompetitive orientation contributes to the consideration of cosmetic surgery independent of body image concerns for both men and women. Keywords: Appearance; Attractiveness; Body Image; Competitiveness; Hypercompetitiveness; Cosmetic Surgery Introduction Physical appearance is well-documented as being an impor- tant characteristic for both women and men and has implications for both intrapersonal well-being and interpersonal interactions (Hatfield & Sprecher, 1986; Jackson, 1992; Langlois et al., 2000). Historically, women are presumed to compete intrasex- ually on the basis of their appearance (Buss, 1989; Darwin, 1871; Fisher & Cox, 2011). As such, it is a woman’s appearance, not her accomplishments, that has been her most valued asset for social and economic survival within a culture (Brownmiller, 1984; Rothblum, 1994; Wolf, 1991). From an early age women are exposed to the sociocultural expectations with regard to their appearance. These norms are pervasively conveyed in the media and frequently depict unat- tainable standards for appearance on which a woman’s worth is based (American Psychological Association, 2007). In addition, there is often the not so subtle implication that women must strive to be more competitive through efforts that enhance their attractiveness (Bessenoff, 2006; Derenne & Beresin, 2006). Not only are these “appearance standards” used to evaluate others, but also they may be internalized and women begin to self-objectify and critically evaluate themselves on the basis of these same standards (Franzoi, 1995; Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997). It is these external and internal pressures that are believed to have resulted in heightened feelings of inadequacy and anxi- ety among women with regard to their physical appearance and body-image and contributes to the prevalence of body dysmor- phia and disordered eating among women (Derenne & Beresin, 2006; Veale, 2004). Appearance concerns also underlie wo- men’s acceptance of cosmetic surgery as a means to boost their self-esteem and enhance their social and career potential (Cal- laghan, Lopez, Wong, Northcross, & Anderson, 2011; Calogero, Pina, Park, & Rahemtulla, 2010; Henderson-King & Brooks, 2009). In contrast to the emphasis placed on women’s appearance, a man’s interpersonal and social attractiveness has traditionally relied more on his apparent skills, abilities, and accomplish- ments rather than physical appearance (Jackson, 1992; Sherrow, 2001). Intrasexual competition among men is based on a display of resource acquisitions (Buss, 1989) and derogation of other men’s abilities and achievements (Buss & Dedden, 1990). However, while objectifying women has had a long history, there has been noted an increasingly obvious trend for objecti- fying men on the basis of their appearance (Faludi, 1999; Moradi & Huang, 2008; Pope, Phillips, & Olivardia, 2000; Sherrow, 2001). Indeed, just as the media has conveyed the cultural standards of appearance for women, men have been increasingly defined by their looks, particularly a youthful appearance and a lean, muscular body (Faludi, 1999; Moradi & Huang, 2008; Sherrow, 2001). As with women, men (and boys) may come to internalize these standards and engage in self-objectification (Moradi & Huang, 2008). Although not to the same degree as women, men are increasingly experiencing appearance and body image con- cerns (Thompson & Cafri, 2007; Thompson, Schaefer, &  B. THORNTON ET AL. Menzel, 2012) with implications for diminished self-esteem, depression, body dysmorphia, disordered eating, and the un- healthy use of steroids and supplements in order to achieve a lean muscularity (Agliata & Tantleff-Dunn, 2004; Cash, 2000; Davis, Karvinen, & McCreary, 2005; Moradi & Huang, 2008; Muth & Cash, 1997; Pope, Gruber, Choi, Olivardi, & Phillips, 1997). Men’s appearance concerns also have implications for con- sidering cosmetic surgery to improve appearance and enhance their social and career potential. The American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS, 2012) reported that, of the 20.2 million pro- cedures performed in the United States, 72% were cosmetic surgeries or minimally invasive procedures undertaken to im- prove one’s appearance, enhance self-esteem, and increase social and career opportunities. Although men are in the minor- ity with regard to undergoing these procedures (9%), the number of procedures among men has increased 22% since 2000. Among the top procedures are those for facial rejuvenation (e.g., facelift, eyelids, botox, skin peel) and achieving a leaner body (e.g., liposuction and breast reduction). Competitive Orientation and Acceptance of Cosmetic Su rgery Horney (1937) had distinguished between two different types of competitiveness. For instance, hypercompetitiveness was considered a psychologically unhealthy competitive orientation based in neurosis. In contrast, a psychologically healthy com- petitive orientation, subsequently referred to as personal de- velopment competitiveness, reflects less concern with task out- come (i.e., win or lose), but more on the self-discovery, self- improvement, and personal growth and development that can be gained through competition. Hypercompetitive Orientation. As originally described by Horney (1937), hypercompetitiveness is an indiscriminate need to compete and win at all costs as a neurotic means to maintain and enhance an otherwise fragile self-esteem. Based in child- hood experiences, this need stems from having authoritarian parents who are abusive and demeaning, and who strongly em- phasize personal success in an achievement-oriented society. Thus, by manipulating, controlling, derogating, or otherwise overcoming others, the hypercompetitive individual is able to deal with feelings of inadequacy. Research has noted that hy- percompetitiveness is indeed a neurotic predisposition and as- sociated with low self-esteem, high anxiety, narcissism, the need to control and dominate others, deceitful and unscrupulous be- havior, and willingness to strategically manipulate impressions for self-aggrandizement (e.g., Dru, 2003; Ross, Rausch, & Canada, 2003; Ryckman, Hammer, Kaczor, & Gold, 1990; Ryckman, Libby, van den Borne, Gold, & Lindner, 1997; Ryck- man, Thornton, & Butler, 1994; Ryckman, Thornton, Gold, & Burckle, 2002; Thornton, Lovley, Ryckman, & Gold, 2009; Watson, Morris, & Miller, 1998). Personal Devel opment Competitive Orientation. In contrast, a personal development competitive orientation is an alternative psychologically healthy perspective. This is characterized by competition with others, not against others; less interest on extrinsic outcomes (i.e., win/lose), but more intrinsic interest in the task itself and the self-evaluation and personal growth gained through competition. Horney (1937) posited that positive child- hood experiences with warm, supportive parents would enable healthy interpersonal relationships and the participation in competitive pursuits with a sense of mutual respect and trust of others. Research has noted that this competitive orientation is related to different psychological and social health indicators, including high self-esteem, achievement and affiliation, em- pathic, altruistic, and forgiving, but not associated with neuroti- cism, dominance, and aggressiveness (e.g., Collier, Ryckman, Thornton, & Gold, 2010; Ryckman & Hamel, 1992; Ryckman, Hammer, Kaczor, & Gold, 1996; Ryckman, Libby, van den Borne, Gold, & Lindner, 1997). Among women, these two competitive orientations have been shown to relate differentially to disordered eating (Burkle, Ryckman, Gold, Thornton, & Audesse, 1999) as well as body dysmorphia and the acceptance and consideration of cosmetic surgery (Thornton, Ryckman, & Gold, 2013). In particular, Thornton et al. reported hypercompetitiveness to be positively related to both body dysmorphia and acceptance of cosmetic surgery, but hypercompetitiveness proved to be a stronger pre- dictor of cosmetic surgery than body dysmorphia. In contrast, personal development competitiveness was negatively related, although not significantly so, to both body dysmorphia and consideration of cosmetic surgery. As such, hypercompetitive women may have a greater need to achieve unrealistic standards of appearance in a neurotic striving to overcome feelings of inferiority and gain advantage over female rivals in physical attractiveness; thus, the greater acceptance of cosmetic surgery as a means to enhance one’s appearance for such purpose. As with women, males today may feel increasingly pressured to achieve media-conveyed societal ideals for appearance and are showing an increased consideration of cosmetic surgery as a means to enhance their appearance, and perhaps their competi- tiveness in personal, social, and career realms. The present research was conducted to examine the relationship hypercom- petitiveness and personal development competitiveness have with body dysmorphia and the acceptance of cosmetic surgery among men. Method Participants and Procedure Participants consisted of a nonclinical sample of 131 Cauca- sian male undergraduates at a public university in the north- eastern United States. Their mean age was 24.27 (SD = 6.49); ages ranged from 18 to 47. In exchange for extra credit in their psychology course, the students completed a set of question- naires for the stated purpose of obtaining baseline data for comparison purposes in subsequent research. In addition to assessments of competitive orientations, body-image, and atti- tudes toward cosmetic surgery (described below), students pro- vided height and weight with which to compute a body mass index (BMI; mean BMI was 25.08, and ranged from 17 to 31). Assessment Instruments Hypercompetitive Attitude (HCA). The 26-item HCA scale is a reliable and valid assessment of individual differences in hypercompetitive attitudes (Ryckman et al., 1990). Sample items are “Winning in competition makes me feel more powerful as a person,” and “If you don’t get the better of others, they will surely get the better of you.” Participants respond to items on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). Scores can range from 26 to 130, with higher scores indicating a stronger hypercompetitive orientation. The Open Access 951  B. THORNTON ET AL. internal consistency of this scale in the present study was ade- quate (α = 0.80). Personal Development Competitive Attitude (PDCA). The 15-item PDCA scale is a reliable and valid assessment of a psychologically healthy competitive orientation concerned more with personal growth and development than individual attain- ment (Ryckman et al., 1996). Sample items are “I value compe- tition because it helps me to be the best that I can be,” and “I enjoy competition because it brings me and my competitors closer together as human beings.” Individual items are re- sponded to on a 5-point scale, strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). Scores can range from 15 to 75, with higher scores indicative of a greater personal development competitive atti- tude. The internal consistency of this scale in the present study was adequate (α = 0.85). Situational Inventory of Body-Image Dysphoria (SIBID). The 20-item SIBID is a reliable and valid assessment of individual differences with regard to people experiencing negative feelings about their bodies (Cash, 2002). Sample items are “I have neg- ative emotional experiences when I look in the mirror,” and “I have negative emotional experiences when I am trying on new clothes at the store.” Items are responded to using a 5-point scale ranging from never (0) to almost always (4). Scores can range from 20 to 80, with higher scores reflecting greater body-image dysphoria. This scale had adequate internal consistency in the present study (α = 0.97). Acceptance of Cosmetic Surgery (ACS). The 15-item ACS scale is a reliable and valid assessment of individuals’ attitudes regarding acceptance of, and propensity for, cosmetic surgery (D. Henderson-King & E. Henderson-King, 2005). Sample items are “I would consider having cosmetic surgery as a way to change my appearance so that I would feel better about myself,” and “If I was offered cosmetic surgery for free, I would consider chang- ing a part of my appearance that I do not like.” Items are re- sponded to on a 5-point scale ranging from not at all (1) to very much (5). Scores can range from 15 to 75, with higher scores indicating greater acceptance of, and interest in having, cosmetic surgery. The internal consistency of the scale in the present study was adequate (α = 0.95). Social Self-Esteem. The Texas Social Behavior Inventory (TSBI; Helmreich & Stapp, 1974) is a reliable and valid 16-item assessment of an individual’s self-esteem reflecting one’s per- ceived level of social comfort and competence. Sample items are “I feel secure in social situations,” and “I enjoy social gatherings with other people.” Item responses used a 5-point scale ranging from not at all (1) to very much (5) characteristic of me. Scores could range from 16 to 80 with higher scores indicative of greater social self-esteem. Internal consistency of this measure in the present study was adequate (α = 0.75). Results Correlat ional Analys e s Pearson correlation coefficients were computed among the different variables and are presented in Table 1. Men’s age correlated positively with BMI (r = 0.23, p < 0.01). While older men had higher BMIs, their age was not related to situational body dysmorphia (r = 0.06). As might be expected, BMI and body dysmorphia were positively related, but not significantly so (r = 0.15). And, while older males generally had higher social self-esteem (r = 0.27, p < 0.01), they also were more favorably disposed toward cosmetic surgery (r = 0.33, p < 0.001), the latter Table 1. Intercorrelations among study variables. Age BMITSBISIBID ACS HCAPDCA Age - 0.23b0.27b0.06 0.33c 0.07 0.06 BMI - 0.02 0.15 0.06 0.22a−0.16 TSBI - −0.32c −0.20a 0.05 0.47c SIBID - 0.42b 0.13 −0.30c ACS - 0.28b0.17 HCA - 0.28b Note: n = 131. ap < 0.05; bp < 0.01; cp < 0.001. consistent perhaps with a youth-oriented cultural atmosphere. Acceptance of cosmetic surgery was also significantly related to body dysmorphia (r = 0.42, p < 0.001), but not BMI (r = 0.06). A similar pattern had been observed previously among women (Thornton et al., 2013). Interestingly, both hypercompetitive- ness and personal development competitiveness were positively correlated with cosmetic surgery acceptance (rs = 0.28, p < 0.01 and 0.17, p < 0.05, respectively). The positive relationship be- tween personal development, an otherwise healthy competitive orientation, and acceptance of cosmetic surgery was unexpected. This is in contrast to a negative relationship reported for women (Thornton et al., 2013) and may be due to a positive relationship between hypercompetitiveness and personal development com- petitiveness among men in the present study (r = 0.28, p < 0.01). Regression Analysis To consider further the two competitive orientations and ac- ceptance of cosmetic surgery, a hierarchical regression analysis was conducted with attitudes toward cosmetic surgery as the criterion. These results are summarized in Table 2. Men’s age, BMI, and social self-esteem were entered as an initial block to control statistically for individual differences on these variables (R2 = 0.12); F(3,127) = 5.83, p < 0.001. This was then followed by a stepwise consideration of body dysmorphia, hypercom- petitiveness, and personal development competitiveness. Body dysmorphia was identified as the next best significant con- tributor to the prediction equation (R2 = 0.34, p < 0.001), F(4,126) = p < 0.001. Hypercompetitiveness was able to contribute further to the regression (R2 = 0.38), F(5,125) = 15.49, p < 0.001. Per- sonal development competitiveness was excluded from entry as it did not contribute significantly to the regression. Discussion Both correlational and regression analyses in the present study demonstrate that the two competitive orientations differ in their relationship to body dysmorphia and attitudes toward cosmetic surgery for men. While hypercompetitiveness was not related to body dysmorphia, it did relate positively with attitudes toward cosmetic surgery. In contrast, personal development competi- tiveness was negatively related to body dysmorphia, but was not significantly related to cosmetic surgery. Moreover, hypercom- petiveness was found to be a significant predictor of acceptance of cosmetic surgery while personal development competitive- ness failed to be of predictive utility in this regard, an outcome that is comparable to previous reports on women (Thornton et al., 2013). Dissatisfaction with one’s physical appearance is typically associated with favorable attitudes toward cosmetic surgery Open Access 952  B. THORNTON ET AL. Table 2. Regression analysis for acceptance of cosmetic surgery. Variable β t R2 ΔR2 Step 1 0.12b Age 0.30 3.35b BMI −0.01 −0.07 TSBI 0.12 1.37 Step 2 0.34b 0.22 Age 0.23 2.99a BMI −0.07 −0.94 TSBI 0.30 3.74b SIBID 0.53 6.52b Step 3 0.38b 0.04 Age 0.25 3.09b BMI −0.11 −1.51 TSBI 0.28 3.61b SIBID 0.48 6.31b HCA 0.51 2.84a Note: Variable excluded at Step 3: PDCA, β = 0.15, t < 1.8, ns. ap < 0.01; bp < 0.001. (Calogero et al., 2010; Slevec & Tiggemann, 2010). Interest- ingly, Menzel et al. (2011) have reported body dissatisfaction to be a stronger determinant of attitudes toward cosmetic surgery among men rather than women. The present findings with men are consistent with this notion in that body dysmorphia entered the regression prior to hypercompetitiveness, whereas in previ- ous research with women (Thornton et al., 2013), body dys- morphia entered the regression following the inclusion of hy- percompetitiveness. The increased emphasis on males’ appearance and the pres- sure on males to achieve some cultural ideal has been attributed, in part, to the increasing equality between men and women in the workplace (Pope et al., 2000). Women have become more able to compete directly with men for power and resources rather than having to “attract a mate” using their appearance. Tradi- tionally, men could rely on skills, abilities, and a display of status and resources to be competitive in the interpersonal mar- ketplace, however, manhood is becoming increasingly defined by youthful appearance and fitness and conveyed through glamorous depictions that objectify and dehumanize, the same issues that were demeaning for women (Faludi, 1999). Never- theless, self-promotion based on their physical attractiveness, body image, and fitness remains a prime strategy among women, and is a common strategy among men as well, in intrasexual competition for the attention of prospective mates (Fisher & Cox, 2011). It would appear that a hypercompetitive orientation may very well contribute further to consideration of enhanced ap- pearance through cosmetic surgery for both women and men independent of body image concerns. In their consideration of social and psychological factors that may contribute to favorable attitudes and behavior toward cos- metic surgery, Menzel et al. (2011) noted the need to identify such characteristics so that clinicians and surgeons might take them into account when determining the suitability of those seeking to undergo such procedures. While surgical and mini- mally invasive procedures may be of psychological and social benefit to those with subclinical (mild-moderate) appearance concerns (Margraf, Meyer, & Lavallee, 2013), such treatments do not reduce the appearance concerns of those with body dysmorphic disorder, and may actually intensify their concerns (Crerand, Franklin, & Sarwer, 2006; Crerand, Menard, & Phil- lips, 2010). Following cosmetic treatments, those with body dysmorphic disorder frequently develop or shift their preoccu- pation to other appearance concerns (Tignol, Biraben-Got- zamanis, Martin-Guehl, & Grabot, 2007; Veale, 2000) and re- petitively undergo cosmetic treatments to correct their perceived appearance defects (Crerand et al., 2010). Body dysmorphic disorder may be an obvious contraindica- tion to cosmetic surgery. Considering the maladaptive nature of hypercompetitiveness, it also may be a personality trait of con- cern in this regard. With a neurotic need to compete and win at all costs in order to cope neurotically with feelings of inade- quacy and feel good about themselves, the appearance domain may be one more arena in which hypercompetitive individuals must strive to best others. With the additional pressure of in- trasexual competition among both men and women, a hyper- competitive orientation may contribute further to consideration of cosmetic surgery in order to be more competitive and ulti- mately “win” in their social and career endeavors. And, like those with body dysmorphic disorder, hypercompetitive indi- viduals may never be satisfied with the results and seek addi- tional treatments in a constant effort to maintain or enhance their competitive advantage through appearance. REFERENCES Agliata, D., & Tantleff-Dunn, S. (2004). The impact of media exposure on males’ body image. Journal of Social and Clinical Psycholo g y , 23, 7-22. http://dx.doi.org/10.1521/jscp.23.1.7.26988 American Psychological Association (2007). Report of the APA task force on the sexualization of girls. Washington, DC: Author. American Society of Plastic Surgeons (2012). Plastic surgery statistics report. http://www.plasticsurgery.org/news-and-resources/2012-plastic-surg ery-statistics.html Bessenoff, G. R. (2006). Can the media affect us? Social comparison, self-discrepancy, and the thin ideal. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 30, 2369-2251. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2006.00292.x Brownmiller, S. (1984). Femininity. New York: Simon & Schuster. Burckle, M. A., Ryckman, R. M., Gold, J. A., Thornton, B., & Audesse, R. J. (1999). Forms of competitive attitude and achievement orienta- tion in relation to disordered eating. Sex Roles, 40, 853-870. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1018873005147 Buss, D. M. (1989). Sex differences in human mate preferences: Evolu- tionary hypotheses tested in 37 cultures. Behavioral and Brain Sci- ences, 12, 1-49. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X00023992 Buss, D. M., & Dedden, L. (1990). Derogation of competitors. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 7, 395-422. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0265407590073006 Callaghan, G. M., Lopez, A., Wong, L., Northcross, J., & Anderson, K. R. (2011). Predicting consideration of cosmetic surgery in a college population: A continuum of body image disturbance and the impor- tance of coping strategies. Body Image, 8, 267-274. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2011.04.002 Calogero, R. M., Pina, A., Park, L., & Rahemtulla, Z. (2010). The role of sexual objectification in college women’s cosmetic surgery atti- tudes. Sex Roles, 63, 32-41. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11199-010-9759-5 Cash, T. F. (2000). Manuals for the appearance schemas inventory, body image ideals questionnaire, multidimensional body-self rela- tions questionnaire, and situational inventory of body-image dyspho- ria. http://www.body-images.com Cash, T. (2002). The situational inventory of body-image dysphoria: Open Access 953  B. THORNTON ET AL. Psychometric evidence and development of a short form. Interna- tional Journal of Eating Disorde rs , 32, 362-366. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/eat.10100 Collier, S. A., Ryckman, R. M., Thornton, B., & Gold, J. A. (2010). Competitive personality attitudes and forgiveness of others. Journal of Psychology, 144, 535-543. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2010.511305 Crerand, C. E., Franklin, M. E., & Sarwer, D. B. (2006). Body dys- morphic disorder and cosmetic surgery. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 118, 1167-1180. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.prs.0000242500.28431.24 Crerarnd, C. E., Menard, W., & Phillips, K. A. (2010). Surgical and minimally invasive cosmetic procedures among persons with body dysmorphic disorder. Annals of Plastic Surgery, 65, 11-16. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/SAP.0b013e3181bba08f Darwin, C. (1871). The descent of man and selection in relation to sex. London: John Murray. Davis, C., Karvinen, K., & McCreary, D. R. (2005). Personality corre- lates of a drive for muscularity in young men. Personality and Indi- vidual Differences, 39, 349-359. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2005.01.013 Derenne, J. L., & Beresin, E. V. (2006). Body image, media, and eating disorders. Academic Psychiatry, 30, 257-261. http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/appi.ap.30.3.257 Dru, V. (2003). Relationships between an ego orientation scale and a hypercompetitive scale: Their correlates with dogmatism and au- thoritarianism factors. Personality and Individual Differences, 35, 1509-1524. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00366-5 Faludi, S. (1999). Stiffed: The betrayal of the American man. New York: Harper Collins. Fisher, M., & Cox, A. (2011). Four strategies used during intrasexual competition for mates. Personal Relationships, 18, 20-38. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.2010.01307.x Franzoi, S. (1995). The body-as-object versus the body-as-process: Gender differences and gender considerations. Sex Roles, 33, 417- 437. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF01954577 Fredrickson, B. L., & Roberts, T. (1997). Objectification theory: To- ward understanding women’s lived experiences and mental health risks. Psychology o f Women Quarterly, 21, 173-206. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00108.x Hatfield, E., & Sprecher, S. (1986). Mirror, mirror...The importance of looks in everyday life. Albany, NY: SUNY Press. Helmreich, R., & Stapp, J. (1974). Short forms of the Texas Social Behavior Inventory (TSBI), an objective measure of self-esteem. Bulletin of the Psychonomi c Society, 4, 473-475. http://dx.doi.org/10.3758/BF03334260 Henderson-King, D., & Henderson-King, E. (2005). Acceptance of cos- metic surgery: Scale development and validation. Body Image, 2, 137-149. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2005.03.003 Henderson-King, D., & Brooks, K. D. (2009). Materialism, sociocul- tural appearance messages, and parental attitudes predict college women’s attitudes about cosmetic surgery. Psychology of Women’s Quarterly, 33, 133-142. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2008.01480.x Horney, K. (1937). The neurotic personality of our time. New York: Norton. Jackson, L. A. (1992). Physical appearance and gender: Sociobiologi- cal and sociocultural p erspectives. Albany, NY: SUNY Press. Langlois, J. H., Kalakanis, L., Rubenstein, A. J., Larson, A., Hallam, M., & Smoot, M. (2000). Maxims or myths of beauty? A meta-ana- lytic and theoretical review. Psychological Bulletin, 126, 390-423. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.126.3.390 Margraf, J., Meyer, A. H., & Lavallee, K. L. (2013). Well-being from the knife? Psychological effects of aesthetic surgery. Clinical Psy- chological Science, 1, 239-252. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/2167702612471660 Menzel, J. E., Sperry, S. L., Small, B., Thompson, J. K., Sarwer, D. B., & Cash, T. F. (2011). Internalization of appearance ideals and cos- metic surgery attitudes: A test of the tripartite influence model of body image. Sex Roles, 65, 469-477. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11199-011-9983-7 Moradi, B., & Huang, Y. (2008). Objectification theory and psychology of women: A decade of advances and future directions. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 32, 377-398. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2008.00452.x Muth, J. L., & Cash, T. F. (1997). Body-image attitudes: What differ- ence does gender make? Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 27, 1438-1452. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1997.tb01607.x Pope, H. G., Gruber, A. J., Choi, P., Olivardia, R., & Phillips, K. A. (1997). Muscle dysmorphia: An unrecognized form of body dys- morphia disorder. Psychosomatics, 38, 548-557. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0033-3182(97)71400-2 Pope, H. G., Phillips, K. A., & Olivardia, R. (2000). The Adonis com- plex: The secret crisis of male body obsession. New York: The Free Press. Ross, S. R., Rausch, M. K., & Canada, K. E. (2003). Competition and cooperation in the five-factor model: Individual differences in achieve- ment orientation. Journal of Psychology, 137, 323-337. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00223980309600617 Rothblum, E. D. (1994). ‘I’ll die for the revolution but don’t ask me not to diet’: Feminism and the continuing stigmatization of obesity. In P. Fallon, M. A. Katzman, & S. C. Wooley (Eds.), Feminist perspec- tives on eating disorders (pp. 53-76). New York: Guilford Press. Ryckman, R. M., & Hamel, J. (1992). Female adolescents’ motives re- lated to involvement in organized team sports. International Journal of Sport Psychology, 23, 147-160. Ryckman, R. M., Hammer, M., Kaczor, L. M., & Gold, J. A. (1990). Construction of a hypercompetitive attitude scale. Journal of Per- sonality Assessment, 55, 620-629. Ryckman, R. M., Hammer, M., Kaczor, L. M., & Gold, J. A. (1996). Construction of a personal development competitive attitude scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 66, 374-386. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa6602_15 Ryckman, R. M., Libby, C. R., van den Borne, B., Gold, J. A., & Lind- ner, M. A. (1997). Values of hypercompetitive and personal devel- opment competitive individuals. Journal of Personality Assessment, 69, 271-283. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa6902_2 Ryckman, R. M., Thornton, B., Gold, J. A., & Burckle, M. A. (2002). Romantic relationships of hypercompetive individuals. Journal of Social and Clinical P s ych olo gy , 21, 517-530. http://dx.doi.org/10.1521/jscp.21.5.517.22619 Ryckman, R. M., Thornton, B., & Butler, J. C. (1994). Personality correlates of the Hypercompetitive Attitude Scale: Validity tests of Horney’s theory of neurosis. Journal of Personality Assessment, 62, 84-94. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa6201_8 Sherrow, V. (2001). For appearance’ sake: The historical encyclopedia of good looks, beauty, and grooming. Westport, CT: Oryx Press. Slevec, S., & Tiggemann, M. (2010). Attitudes toward cosmetic surgery in middle aged women: Body image, aging anxiety, and the media. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 34, 65-74. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2009.01542.x Thompson, J. K., & Cafri, G. (2007). The muscular ideal. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/11581-000 Thompson, J. K., Schaefer, L., & Menzel, J. (2012). Internalization of the thin and muscular ideal. In T. F. Cash (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Body Image and Human Appearance (pp. 499-504). Waltham, MA: Academic Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-384925-0.00079-1 Thornton, B., Lovley, A., Ryckman, R. M., & Gold, J. A. (2009). Play- ing dumb and knowing it all: Competitive orientation and impression management strategies. Individual Differences Research, 7, 265-271. Thornton, B., Ryckman, R. M., & Gold, J. A. (2013). Competitive ori- enttations and women’s acceptance of cosmetic surgery. Psychol- ogy: Individual Development, 4, 67-72. Tignol, J., Biraben-Gotzamanis, L., Martin-Guehl, C., Grabot, D., & Aouiz- erate, B. (2007). Body dysmorphic disorder and cosmetic surgery: Evo- lution of 24 subjects with a minimal defect in appearance 5 years after their request for cosmetic surgery. European Psychiatry, 22, 520-524. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2007.05.003 Veale, D. (2000). Outcome of cosmetic surgery and ‘DIY’ surgery in patients with body dysmorphic disorder. The Ps ychiatri st, 24, 218-221. Open Access 954  B. THORNTON ET AL. Open Access 955 http://dx.doi.org/10.1192/pb.24.6.218 Veale, D. (2004). Advances in a cognitive behavioral model of body dysmorphic disorder. Body Image, 1, 113-125. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1740-1445(03)00009-3 Watson, P. J., Morris, R. J., & Miller, L. (1998). Narcissism and the self as continuum: Correlations with assertiveeness and Hypercom- petitiveness. Imag ination, Cognition, a nd Personality, 17, 249-259. http://dx.doi.org/10.2190/29JH-9GDF-HC4A-02WE Wolf, N. (1991). The beauty myth: How images of beauty are used against women. New York: William Morrow and Company.

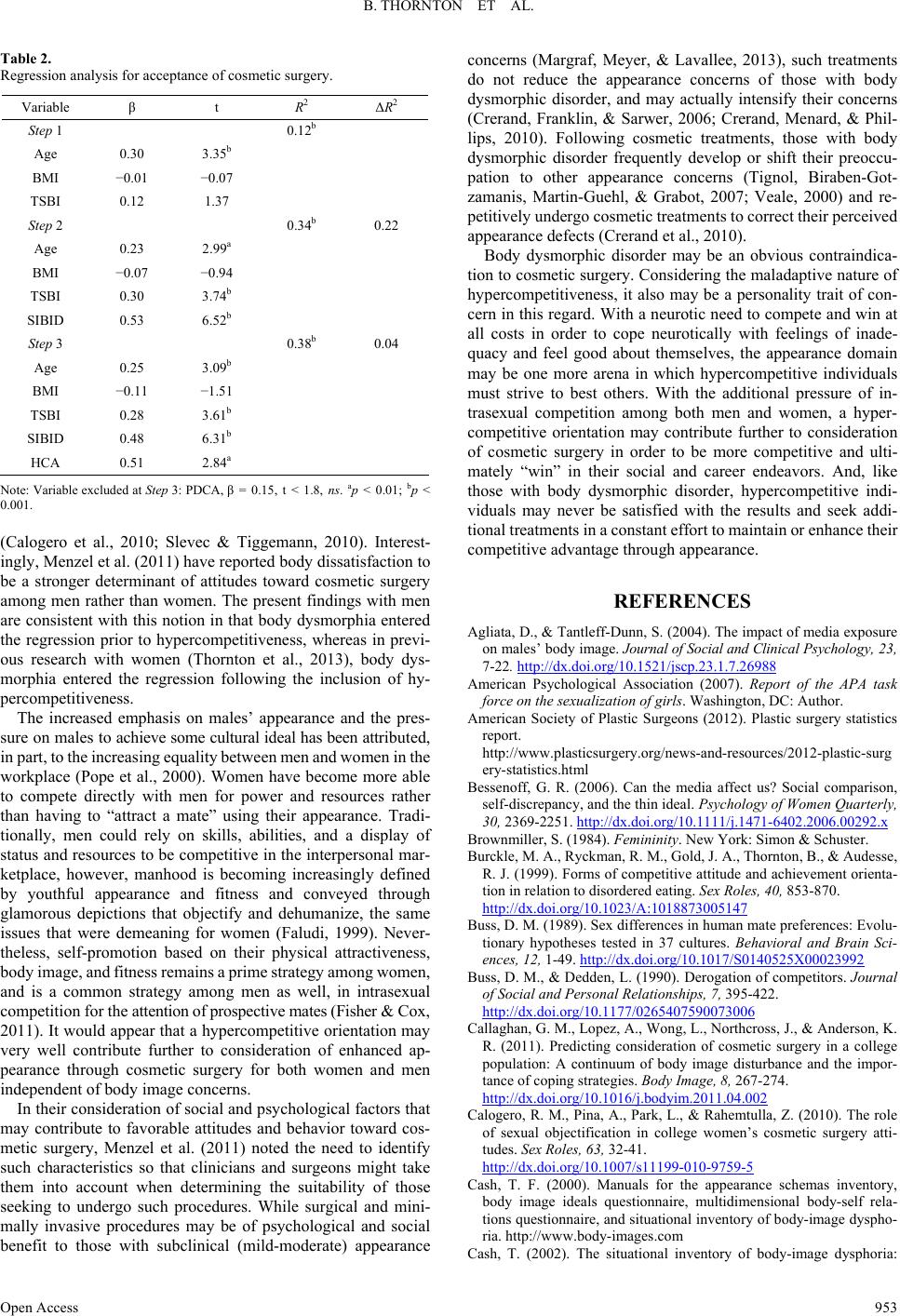

|