International Journal of Otolaryngology and Head & Neck Surgery, 2013, 2, 240-244 Published Online November 2013 (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ijohns) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ijohns.2013.26050 Open Access IJOHNS Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Oropharynx Presenting with Distant Metastasis to the Ulna Preetham Achoor Puthukudy*, Musarrat Feshan Southern Railway HQ Hospital, Chennai, India Email: *preetham.ap@gmail.com, dr.feshan@gmail.com Received August 1, 2013; revised September 2, 2013; accepted September 30, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Preetham Achoor Puthukudy, Musarrat Feshan. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Com- mons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. ABSTRACT Squamous cell carcinomas are the commonest malignancies of the head and neck. Metastases from stage III and stage IV tumors occur most commonly in the cervical lymph nodes. The incidence of distant metastases occurring from such advanced tumors is anywhere between 10% and 40%. Distant metastases occur most commonly to the lungs followed by the bone and liver. The bone metastasis occurs commonly in the axial skeleton. We report a rather unusual case of squamous cell carcinomas from the Head and Neck region in a 77-year-old male metastasizing to the ulna. This case is even more interesting because the presenting symptom was a pathological fracture of the ulna for which he had reported to the orthopedic department. The immunohistochemistry of the metastatic tumor had shown an unmistakable squamous cell carcinoma with positive cytokeratin elements within the tumor. He referred to the ENT department where he was diagnosed with T2N0M1 squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx. The patient was treated with internal fixation and bone cementing for the metastatic lesion, and primarily treated with chemoradiation. Keywords: Squamous Cell Carcinoma; Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma (OPSCC); Oropharynx; Distant Metastasis; Ulna; Head and Neck Can cer; Pathological Fracture 1. Introduction Squamous cell carcinomas are the commonest malignan- cies of the head and neck accoun ting for over 90% of the tumors. Distant metastasis from carcinoma arising in the head and neck is generally considered to be infrequent and even when it occurs it is mostly from stage III and stage IV tumors [1,2]. The frequency of distant metasta- ses does not correlate with the size of the primary lesion, but correlates with the appearance of cervical node me- tastases regardless of location in the neck [3]. The com- monest site of distant metastasis is the lung followed by the bone and liver [4]. In the bones, the metastasis is commoner in the axial skeleton—recorded mainly in the spine, pelvis, sacrum, skull, ribs and clavicle [2]. We report a rare case of oropharyngeal carcinoma with no neck nodes where the presenting complaint was a patho- logical fracture from the distant metastasis in the ulna. 2. Case Report A 77-year-old male presented with a pathological frac- ture of the right ulna, after a trivial injury against an autorickshaw, to the Southern Railway Headquarters Hos- pital, Ayanavaram, Chennai. He was a chronic smoker who smoked about 30 - 40 cigarettes per day for many years but did not have any complaint related to the head and neck. He attended the orthopedic department of our hospital with pain, swelling and deformity of his right forearm (Figure 1). X-Ray showed an osteolytic lesion (Figure 2). An open biopsy and curettage was done fol- lowed by Locking Compression Plate (LCP) fixation, bone cementing with intramedullary K wire fixation. Subsequently he was referred to the ENT department to search for a primary which revealed a proliferative mass in the right vallecula extending to the right aryepiglottic fold. Both vocal cords were normal and mobile. Biopsy was taken from the oropharyngeal growth and sent for HPE. At this stage no neck nodes were palpable. CT abdomen showed some non-specific irregular wall thickening in the region of D1 and D2 segments of the duodenum and in the region of descending colon. CT chest revealed a few pretracheal and paratracheal lymph nodes and some evidence of an old pulmonary Koch’s *Corresponding author.  P. A. PUTHUKUDY, M. FESHAN 241 Figure 1. Right forearm showing deformity due to the pathological fracture of the ulna. Figure 2. Pre-op X-ray showing pathological fracture of the right ulna. lesion. Radioisotope bone scan showed a central photo- penic area with an increased skeletal uptake in the right ulna (Figure 3). Upper GI endos copy was normal. An open biopsy was performed during the curettage, LCP and intramedullary K-wire fixation and multiple tissue material, the largest measuring 4 × 2 × 2 cm, was sent for HPE. It revealed a bony trabeculae and sur- rounding fibrocollagenous tissue infiltrated by a malig- nant neoplasm composed of basaloid cells with hyper- chromatic nuclei arranged in nests, trabeculae and cri- briform pattern. Numerous mitotic figures and foci of Figure 3. Radioisotope bone scan showing a central photo- penic area with an increased skeletal uptake in the right ulna. necrosis were seen. The intervening fibrotic stroma showed lympho-plasmacytic infiltrate. The tumor was seen infiltrating into the surrounding muscle. These find- ings were consistent with a metastatic poorly differenti- ated carcinoma. Immunohistochemistry of the metastatic tumor showed that it was positive for cytokeratin, cy- tokeratin 7 and cytokeratin (high molecular weight); and was negative for PSA, PSAP, TTF, synaptophysin, CEA, CDX2 and cytokeratin 20. This is consistent with a poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma. The bi- opsy report from the oropharyngeal lesion showed mu- cosa lined by squamous epithelium and a neoplasm com- posed of atypical cells with hyperchromatic, pleomorphic nuclei and scanty cytoplasm arranged in sheets and perivascular pattern. Mitotic figures and foci of necrosis were also seen. The clinical staging of the tumor was T2N0M1, Stage IV disease. Chemoradiation was considered the best op- tion in this case. Linear Accelerator Radiotherapy was given along with Chemotherapy with Cisplatin 100 mg IV every week for 6 weeks. A total dose of 60 Gy was given over 30 sessions, five days a week for 6 weeks. The patient completed Chemo radiotherapy but was lost to follow up. 3. Discussion Head and neck cancers account for less than 5% of all cancers. Squamous cell carcinoma is the commonest ma- lignancy of the head and neck region accounting for al- most 90% of the tumors [5]. It is also the commonest malignancy of the oropharynx. Oropharyngeal squamous Open Access IJOHNS  P. A. PUTHUKUDY, M. FESHAN 242 cell carcinoma, OPSCC, represents 10% - 15% of all head and neck tumors and has an annual incidence of 10 per million per year in the UK [6]. There is an increasing prevalence of oral and oropharyngeal cancers in the last decade, particularly in men aged 35 - 64 years [7]. The condition is commoner in men, with a sex ratio of 4:1, and is common in the sixth and seventh decades of life. The frequency distribution of the primary site carcinoma in the oropharynx is tonsil or fauc ial pillar 45%, posterior tongue 40%, soft palate 15% and posterior pharyngeal wall 5% [8]. The main associated etiological factors are smoking and alcohol consumption, the effects of which are cumulative [9]. Dietary deficiencies of vitamin A, chronic irritants, poor dental hygiene, syphilis and mari- juana smoking have also been identified as predisposing factors in upper aerodigestive tract cancers [10]. The effect of HPV-16 has been profound on OPSCC. It is this effect which is responsible for the increase in the inci- dence of OPSCC over the last decade or more, so that now as much as 50% of OPSCC is thought to be HPV induced [11]. When present, the initial symptom of an oropharyn- geal malignancy is often vague and nonspecific, leading to a delay in diagnosis. Consequently, the overwhelming majority of such patients has locally advanced tumors when they present [12]. Other more serious symptoms that require investigation include sore throat, foreign- body sensation in the throat, altered voice or referred pain to the ear, through the glossopharyngeal and vagus nerves [13] . Distant metastases are a significant problem in patients with carcinoma of oropharynx, and happen in approxi- mately 15% - 20% of all such patients ov er the course of their disease. The spread is the commonest to the lungs, in patients with advanced disease, and especially in those with histologically proven lymph nodes at multiple levels of the neck or in the lower neck [14]. The overall inci- dence of clinically detected distant metastasis in head and neck squamous cancers is 9% - 11% [15]. Among head and neck cancers, nasopharynx has the highest in- cidence of distant metastasis while laryngeal cancers especially those of the vocal cords have the lowest inci- dence [4]. Distant metastases occur more commonly with larger primary tumors [4,16,17]. Some studies have noted a higher rate of distant metastasis from less differentiated head and neck squamous cell cancers while others have failed to find any such association [18]. The incidence of distant metastasis varies significantly from the T and N stage (T1-2 is 7.87%, T3-4 is 14%, N0-1 is 6.3%, and the N2-3 is 24%); the N stage has greater influence but Berger and Fletcher found no connection between the size of the primary tumor and the development of distant metastases [3]. Patients with three or more clinical lymph node me- tastases or low jugular lymph node metastases, bilateral lymph node metastases, lymph nodes of 6 cm or larger have a higher incidence of distant metastases [19]. Crile reported in 1923 that 1% of patients with head and neck cancer developed distant metastases. Clinical data in recently reported studies indicate an incidence of 5% to 24% whereas autopsy series reports an incidence of 17% - 47% [1]. Distant metastases were found in 12.3% of patients in a study by Probert et al. in 1974 [2]. As local and regional control of head and neck cancer has improved, distant metastases have become an in- creasingly common cause of death [20]. Only a limited number of studies have reported on the incidence of dis- tant metastases at presentation. Dennington et al. and Black et al. have found distant metastases at presentation in 7% - 12% of patients in advanced stage disease re- spectively [21,22]. The average time for the development of distant metastasis is about 10 to 12 months after the initial diagnosis. Most distant metastases from head and neck cancers become apparent within the first two years of the initial diagnosis [23]. The commonest site of distant metastasis was the lung followed by bone, liver, skin, brain and adrenal gland. Unexpected sites such as heart, peritoneum, esophagus and spleen were also seen. In the bone, the commonest site was the dorsal spine followed by the lumbar spine, skull, ribs, pelvis and sacrum. Among the long bones, femur was the only bone recorded to have distant metas- tasis [2]. Pathologic fracture can be the presenting condition of patients with metastatic disease. Osteolytic lesions are predominantly responsible for pathologic fractures. How- ever, fractures can also occur in mixed or osteoblastic lesions because tumor-related bone lacks structural in- tegrity. Higinbotham, in a review of 1800 cancer patients, found an 8% incidence of pathologic fracture [24]. Breast carcinoma is the cause of the majority of pathologic fractures due to metastatic disease. Other malignancies, each is responsible for 5% - 10% of such pathological fractures, including kidney, lung, and thyroid carcinoma, and lymphoma [24]. Of all long bone fractures due to metastatic disease, 60% involve the femur; the majority of these (80%) involve the proximal portion [25]. The treatment of a patient with advanced malignant disease is fraught with a multitude of problems [26,27]. A variety of interrelated factors must be considered when choosing the appropriate treatment for a patient who presents with a tumour located in the oropharynx. Ulti- mately, the treatment must be suited to each patient [28]. Most oropharyngeal tumours are operable, but whether they are curable by surgery alone is debatable. The sur- gical principles which continue to be advocated are that resection must include a margin of 1 - 2 cm of grossly normal tissue. Oropharyngeal cancers can be resected Open Access IJOHNS  P. A. PUTHUKUDY, M. FESHAN 243 through three main surgical approaches: the transoral, transpharyngeal, and the transmandibular approaches. T he choice of approach depends on the size and location of the tumour, and whether a concomitant neck dissection is being planne d and the m e t hod of reconstruct i on [2 9] . The 1990s saw the introduction and increasing use of definitive concomitant chemoradiotherapy which offer- ing better survival compared to radiotherapy [30]. There is an agreement that T1, T2, and some T3 tumours of the oropharynx respond well to radiotherapy [31]. Alterna- tive methods for delivering radiotherapy have been ad- vocated with the use of interstitial or intracavity implan- tation of radioactive sources into the tumour [32,33]. The combination of surgery and postoperative radio- therapy is becoming more popular and there is an appre- ciable improvement in locoregional disease [34]. With the additional advantage of concomitant chemoradio- therapy, the balance has fallen to chemoradiotherapy over surgery and this has now become the standard of care for most patients with oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma [35]. Chemoradiotherapy has evolved to be general in the form of induction chemotherapy with three cycles of TPF (docetaxel-cisplatin-5 flourouracil) and then concurrent chemoradiotherapy with platinum [36, 37]. REFERENCES [1] C. W. Crile, “Carcinoma of the Jaws, Tongue, Cheek, and Lips,” Surgery Gynecology & Obstetrics, Vol. 36, 1923, pp. 159-184. [2] J. C. Probert, R. W. Thompson and M. A. Bagshaw, “Pat- terns of Spread of Distant Metastasis in Head and Neck Cancer,” Cancer, Vol. 33, No. 1, 1974, pp. 127-133. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/1097-0142(197401)33:1<127:: AID-CNCR2820330119>3.0.CO;2-L [3] D. S. Berger and C. H. Fletcher, “Distant Metastasis Fol- lowing Local Control of Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Nasopharynx, Tonsillar Fossa, and Base of Tongue,” Ra- diology, Vol. 100, 1971, pp. 141-143. [4] M. R. Orlando, L. Robert and F. D. Gilbert, “An Analysis of Distant Metastases from Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Upper Respiratory and Digestive Tracts,” Cancer, Vol. 40, No. 1, 1977, pp. 45-151. [5] S. Marur and A. A. Forastiere, “Head and Neck Cancer: Changing Epidemiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment,” Mayo Clinic Proceedings, Vol. 83, No. 4, 2008, pp. 489-501. http://dx.doi.org/10.4065/83.4.489 [6] P. J. Bradley, “Management of Squamous Cell Carci- noma of the Oropharynx,” Current Opinion in Otolaryn- gology and Head and Neck Surgery, Vol. 8, No. 5, 2000, pp. 80-86. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00020840-200004000-00002 [7] K. L. Robinson and G. J. Macfarlane, “Oropharyngeal Cancer Incidence and Mortality in Scotland: Are Rates Still Increasing?” Oral Oncology, Vol. 39, No. 1, 2003, pp. 31-36. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1368-8375(02)00014-3 [8] S. Mak-Kregar, F. J. M. Hilgers, P. C. Levendag, J. J. Manni, H. Lubsen, J. L. Roodenburg, et al., “A Nation- wide Study of the Epidemiology, Treatment and Survival of Oropharyngeal Carcinoma in the Netherlands,” Euro- pean Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology, Vol. 252, No. 3, 1995, pp. 133-138. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF00178098 [9] J. S. Tobias, “Cancer of the Head and Neck,” British Medical Journal, Vol. 308, 1994, pp. 961-966. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.308.6934.961 [10] P. J. Donald, “Marijuana Smoking: Possible Cause of Head and Neck Cancer in Young Patients,” Otolaryngol- ogy and Head and Neck Surgery, Vol. 94, No. 4, 1986, pp. 517-521. [11] M. Romanitan, A, Nasman, T. Ramqvist, H. Dahlstrand, L. Polykretis, P. Vogiatzis, et al., “Human Papillomavirus Frequency in Oral and Oropharyngeal Cancer in Greece,” Anticancer Research, Vol. 28, No. 4B, 2008, pp. 2077- 2080. [12] M. Pitchers and C. Martin, “Delay in Referral of Oro- pharyngeal Carcinoma to Secondary Care Correlates with a More Advanced Stage at Presentation, and Is Associ- ated with Poorer Survival,” British Journal of Cancer, Vol. 94, No. 7, 2006, pp. 955-958. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6603044 [13] J. B. Patrick, “Oropharyngeal Tumors,” In: G. Michael, Ed., Scott-Brown’s Otorhinolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery, 7th Edition, Hodder Arnold, London, 2008, pp. 2577-2597. [14] W. J. Goodwin, “Distant Metastases from Oropharyngeal Cancerm,” Journal for Oto-Rhino-Laryngology and Its Related Specialties, Vol. 63, No. 4, 2001, pp. 222-223. http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000055745 [15] C. R. Leemans, R. Tiwari, J. J. P. Nauta, I. van der Waal and G. B. Snow, “Regional Lymph Node Involvement and Its Significance in the Development of Distant Me- tastasis in Head and Neck Carcinoma,” Cancer, Vol. 71, No. 2, 1993, pp. 452-456. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/1097-0142(19930115)71:2<452 ::AID-CNCR2820710228>3.0.CO;2-B [16] S. Kramer, V. A. Marcial, T. K. Pajak, C. J. MacLean and L. W. Davis, “Prognostic Factors for Loco/Regional Con- trol and Metastases and the Impact on Survival,” Interna- tional Journal of Radiation Oncology • Biology • Physics, Vol. 12, No. 4, 1986, pp. 573-578. [17] R. J. Papack, “Distant Metastases from Head and Neck Cancer,” Cancer, Vol. 53, No. 2, 1984, pp. 342-345. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/1097-0142(19840115)53:2<342 ::AID-CNCR2820530228>3.0.CO;2-9 [18] G. F. Gowen and G. Desuto-Nagy, “The Incidence and Sites of Distant Metastasis in Head and Neck Carci- noma,” Surgery Gynecology & Obstetrics, Vol. 47, 1963, pp. 603-607. [19] D. B. Remco, E. D. Elene, B. S. Gordon and R. L. C har l es, “Screening for Distant Metastases in Patients with Head and Neck Cancer,” Laryngoscope, Vol. 110, No. 3, 2000, pp. 397-401. Open Access IJOHNS  P. A. PUTHUKUDY, M. FESHAN Open Access IJOHNS 244 http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00005537-200003000-00012 [20] B. Vikram, E. W. Strong, J. P. Shah and R. Spiro, “Fail- ure at Distant Sites Following Multi Modality Treatment for Advanced Head and Neck Cancer,” Head and Neck Surgery, Vol. 6, No. 3, 1984, pp. 730-733. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/hed.2890060305 [21] M. L. Dennington, D. R. Carter and A. D. Meyers, “Dis- tant Metastases in Head and Neck Epidermoid Carci- noma,” Laryngoscope, Vol. 90, No. 2, 1980, pp. 196-201. http://dx.doi.org/10.1288/00005537-198002000-00002 [22] R. J. Black, J. L. Gluckman and D. A. Shumrick, “Scr een- ing for Distant Metastases in Head and Neck Cancer Pa- tients,” Australian and New Zealand Journal of Surgery, Vol. 54, No. 6, 1984, pp. 527-530. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1445-2197.1984.tb05440.x [23] H. C. Karen, F. Paul, W. Raymond and A. H. James, “Distant Metastases from Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma,” Laryngoscope, Vol. 104, No. 10, 1994, pp. 1199-1205. [24] N. L. Higinbotham and R. C. Marcove, “The Manage- ment of Pathological Fractures,” Journal of Trauma, Vol. 5, No. 6, 1965, pp. 792-798. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00005373-196511000-00015 [25] F. H. Sim, “Instructional Course Lectures: Meta static B on e Disease,” In: Instructional Course Lectures, Vol. 49, American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, Anaheim, 1999. [26] L. B. Harrison, A. Ferlito, A. R. Shaha, P. J. Bradley and A. Rinaldo, “Current Philosophy on the Management of Cancer of the Base of Tongue,” Oral Oncology, Vol. 39, No. 2, 2003, pp. 101-105. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1368-8375(02)00048-9 [27] W. Zhen, L. H. Karnell, H. T. Hoffman, G. F. Funk, J. M. Buatti and H. Menck, “The National Cancer Data Base Report on Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Base of Tongue,” Head and Neck, Vol. 26, No. 8, 2004, pp. 660- 674. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/hed.20064 [28] K. Sundaram, J. Schwartz, G. Har-El and F. Lucente, “Carcinoma of the Oropharynx: Factors Affecting Out- come,” Laryngoscope, Vol. 115, No. 9, 2005, pp. 1536- 1542. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.mlg.0000175075.69706.64 [29] C. G. Gourin and J. T. Johnson, “Surgical Treatment of Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Tongue,” Head and Neck, Vol. 23, No. 8, 2001, pp. 653-660. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/hed.1092 [30] G. Calais, M. Alfonsi, E. Bardet, C. Sire, T. Germain, P. Bergerot, et al. , “Randomized Trial of Radiation Therapy versus Concomitant Chemotherapy and Radiation Ther- apy for Advanced Stage Oropharynx Carcinoma,” Jour- nal of National Cancer Institute, Vol. 91, No. 24, 1999, pp. 2081-2086. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jnci/91.24.2081 [31] U. Selek, A. S. Garden, W. H. Morrison, A. K. El-Naggar, D. I. Rosenthal and K. K. Ang, “Radiation Therapy for Early Staged Carcinoma of the Oropharynx,” Interna- tional Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics, Vol. 59, No. 3, 2004, pp. 743-751. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2003.12.002 [32] L. B. Harrison, “Applications of Brachytherapy in Head and Neck Cancer,” Seminars in Surgical Oncology, Vol. 13, No. 3, 1997, pp. 177-184. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1098-2388(199705/06)13 :3<177::AID-SSU4>3.0.CO;2-4 [33] D. M. Kaylie, K. R. Ste vens, M. Y. Kang, J. I. Cohen, M. K. Wax and P. E. Anderson, “External Beam Radiation Followed by Planned Neck Dissection and Brachytherapy for Base of Tongue Squamous Cell Carcinoma,” Laryn- goscope, Vol. 110, No. 10, 2000, pp. 1633-1636. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00005537-200010000-00011 [34] A. S. Denittis, M. Machtay, D. I. Rosenthal, N. J. Sanfil- lippo, J. H. Lee, S. Goldfeder, et al., “Advanced Oro- pharyngeal Carcinoma Treated with Surgery and Radio- therapy: Oncologic Outcome and Functional Assess- ment,” American Journal of Otolaryngology, Vol. 22, No. 5, 2001, pp. 329-335. http://dx.doi.org/10.1053/ajot.2001.26492 [35] A. Y. Chen, N. Schrag, Y. Hao, A. Stewart and E. Ward, “Changes in Treatment of Advanced Oropharyngeal Can- cer. 1985-2001,” Laryngoscope, Vol. 1, No. 17, 2007, pp. 16-21. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.mlg.0000240182.61922.31 [36] J. P. Pignon, N. Syz, M. Posner, R. Olivares, L. Le Lann, A. Yver, et al., “Adjusting for Patient Selection Suggests the Addition of Docetaxel to 5-Fluorouracil-Cisplatin In- duction Therapy May Offer Survival Benefit in Squamous Cell Cancer of the Head and Neck,” Anticancer Drugs, Vol. 15, No. 4, 2004, pp. 331-340. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00001813-200404000-00004 [37] M. R. Posner, D. M. Hershock, C. R. Blajman, E. Mickiewicz, E. Winquist, V. Gorbounova, et al., “Cis- platin and Fluorouracil Alone or with Docetaxel in Head and Cancer,” New England Journal of Medicine, Vol. 354, No. 6, 2006, pp. 567-578.

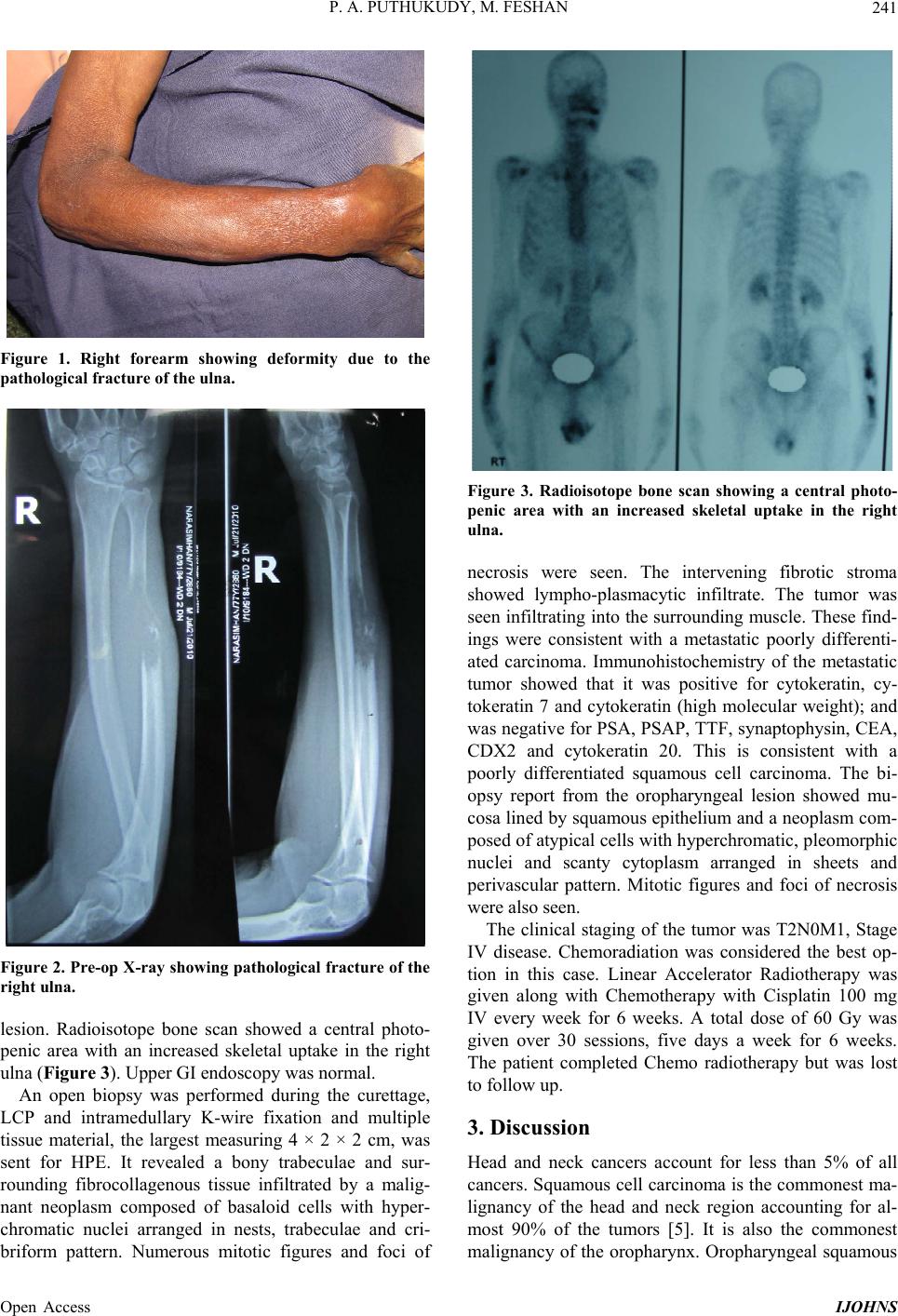

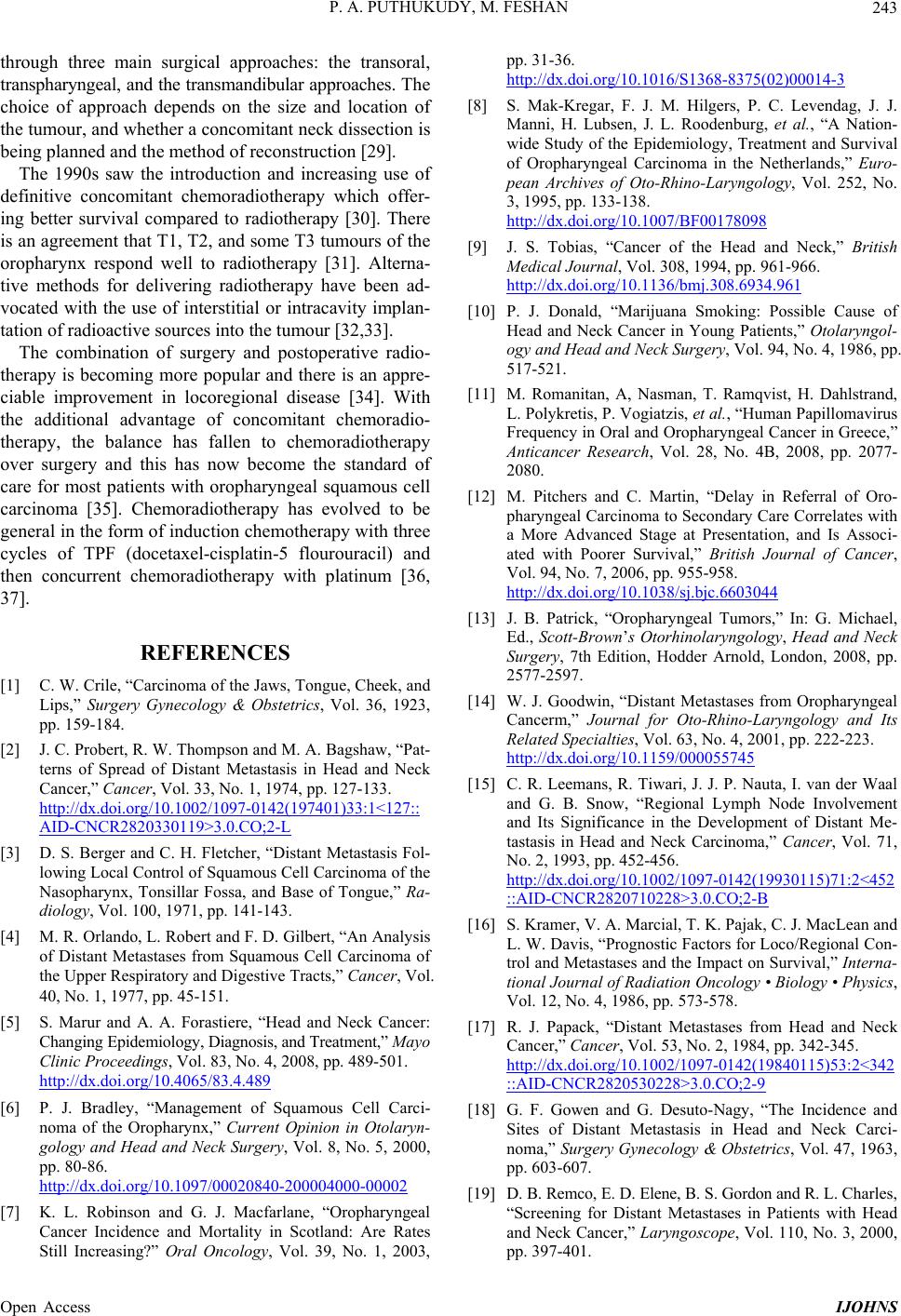

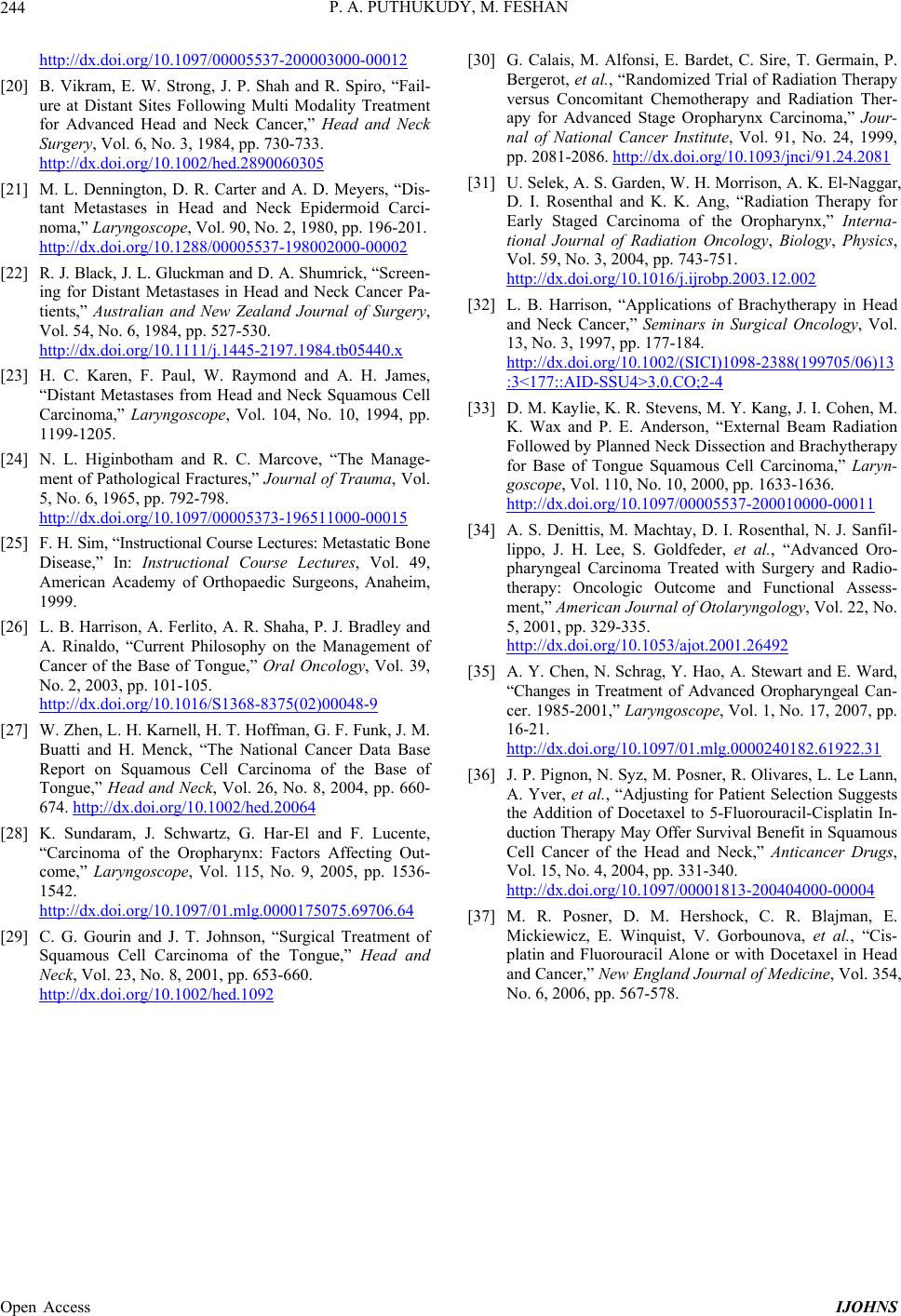

|