Advances in Materials Physics and Chemistry

Vol.06 No.07(2016), Article ID:67958,18 pages

10.4236/ampc.2016.67019

Examples of Non-Uniqueness of the Equilibrium States for a Floating Ball

Ray Treinen

Department of Mathematics, Texas State University, San Marcos, Texas, USA

Copyright © 2016 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 26 April 2016; accepted 2 July 2016; published 5 July 2016

ABSTRACT

We provide a numerical algorithm for numerically approximating a centrally located floating ball. We give examples of equilibria, and we present non-unique cases for the same physical parameters when the density of the ball is either greater than the supporting liquid (heavy) or lighter than the density of the vapor above (light). We classify the non-uniqueness by analyzing a function related to the force balance. We derive the potential energy of these states, and make comparisons of the non-unique cases. In the cases of both the light and heavy floating balls, the evidence presented supports the conjecture that when there are two equilibria, the one with lower energy corresponds to the location of triple junction (between the ball, the vapor and the liquid) that is closer to the equator of the ball.

Keywords:

Floating Ball, Capillarity

1. Introduction

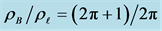

Consider a ball of density  floating at the surface of a fluid that has density

floating at the surface of a fluid that has density . We present numerical examples of non-uniqueness of the equilibrium states for these configurations. We will also provide a framework for the classification of these states, including an energy analysis. The energy analysis is used to determine which of the two equilibria has the lower energy, and thus, at least amongst centrally located floating balls, this process finds the energy minimizing configuration. Under these conditions, this is the configuration that our model predicts which will be found in experiments. We begin with a precise formulation of our model.

. We present numerical examples of non-uniqueness of the equilibrium states for these configurations. We will also provide a framework for the classification of these states, including an energy analysis. The energy analysis is used to determine which of the two equilibria has the lower energy, and thus, at least amongst centrally located floating balls, this process finds the energy minimizing configuration. Under these conditions, this is the configuration that our model predicts which will be found in experiments. We begin with a precise formulation of our model.

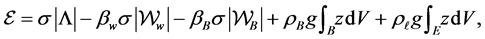

The energies considered in this model are due to the surface tension and gravity. Surface tension energy is taken, as usual, to be proportional to the area of the free surface with proportionality constant  called the surface tension constant. The energy due to gravity consists of two terms, one corresponding to the liquid and another to the floating object. The former is proportional to the density of the liquid,

called the surface tension constant. The energy due to gravity consists of two terms, one corresponding to the liquid and another to the floating object. The former is proportional to the density of the liquid,  , a gravitational constant, and a volume integral of the physical height, z, in the gravity field. The latter is similar except the density of the floating object,

, a gravitational constant, and a volume integral of the physical height, z, in the gravity field. The latter is similar except the density of the floating object,  , is used, and the integral is taken over the volume of the floating object. If we denote the floating ball by B, the liquid by E, and

, is used, and the integral is taken over the volume of the floating object. If we denote the floating ball by B, the liquid by E, and  the free liquid-air interface,

the free liquid-air interface,  the wetted portion of the bounding walls, if they exist,

the wetted portion of the bounding walls, if they exist,  the wetted portion of the floating ball. Then the energy of this configuration is given by

the wetted portion of the floating ball. Then the energy of this configuration is given by

(1)

(1)

with wetting coefficients  and

and , depending on contact angles

, depending on contact angles  and

and  at the contact with the ball and the wall, respectively. Here z is height in the vertical direction, and

at the contact with the ball and the wall, respectively. Here z is height in the vertical direction, and  is the volume measure. Also,

is the volume measure. Also,  denotes surface area, calculated using a Hausdorff measure, as appropriate. It is often convenient to refer to the mathematical energy of the system, which is merely the scaled energy

denotes surface area, calculated using a Hausdorff measure, as appropriate. It is often convenient to refer to the mathematical energy of the system, which is merely the scaled energy

with “capillary constant”

The natural physical setting for these problems is in a bounded container in

The goal of this note is to provide numerically computed approximations to some sample configurations when the ball is centrally located in the container and the fluid is assumed to be symmetric about the central axis. We will focus on the cases of the density

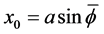

With this setting established, we are able to proceed to the configurations of interest. Assume that the ball floats centrally, and so that the center of the ball is at a height d. Thus the boundary of the ball can be described by its azimuthal angle

where

where

when the surface is a graph over some base domain. However, we will not restrict ourselves to these limited configurations. We have boundary conditions

where

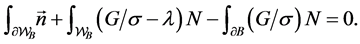

In [1] , we derived an additional necessary condition that does not appear in the classical literature consisting of fluid interactions with rigid solid objects. A manuscript by Finn [3] is the standard reference for the classical literature. We need to define several objects before we can state this condition. Denote the volume of fluid by

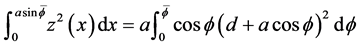

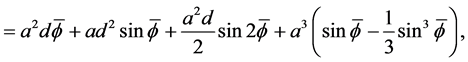

energy due to gravity is measured as

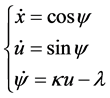

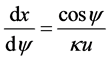

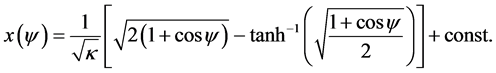

Under the assumption of symmetry about the vertical axis, the PDE with boundary conditions can be reduced to

This representation of the equation allows for the parameterized curve to pass through both inflection points and vertical points. Various authors have studied this system with differing boundary conditions and also as a family of solution curves. Solutions are sometimes known as Euler elastica. See Aspley, He, and McCuan [4] , Euler [5] , Giaquinta and Hildebrandt [6] (pp. 142-144), McCuan [7] and [8] , and Wente [9] for both historical origins, as well as applications to capillarity.

Then (2) becomes

and we define

We seek solutions to (3) that satisfy (4) and

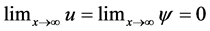

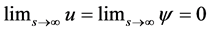

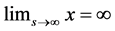

If we replace the bounded container with an infinite sea of liquid, then we follow Bhatnagar and Finn [10] in taking the Lagrange multiplier

Before moving on to these details we would like to mention some other authors and their works on floating objects: Bemelmans, Galdi, Kyed [11] , Bhatnagar and Finn [10] , Finn [12] - [14] , Finn, McCuan, and Wente [15] , Finn and Sloss [16] , Finn and Vogel [17] , Kemp and Siegel [18] , McCuan [2] , Vella [19] , Vella and Mahadevan [20] , Vella, Lee, and Kim [21] , and Vella, Metcalfe, and Whittaker [22] . In particular, as pointed out in [19] , a number of applications have been of recent interest, for some examples, see capillary-driven self-assembly Whitesides and Boncheva [23] and Whitesides and Grzybowski [24] , the stabilization of emulsions by colloidal particles (Binks and Horozov [25] , Tavacoli, Katgert, Kim, Cates and Clegg [26] ), the locomotion of insects and spiders on water (Bush and Hu [27] , Gao and Jiang [28] ), and the design and optimization of biomimetic water-walking robots (Hu, Chan and Bush [29] , Ozcan, Wang, Taylor and Sitti [30] , Song and Sitti [31] ).

2. Methods

We will consider first the bounded container in

Next we illustrate how the new free boundary condition can be used to determine when there is non uni- queness of the equilibria. We give numerical examples. Finally, in the case of the bounded container, we calculate the potential energy of each configuration and compare the energy of the two configurations with the same physical properties.

2.1. Bounded Container in R2

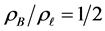

We first need to measure the volume of fluid held in the container. One may compute

Our formula does not require that the height u is a function over a base domain.

In what follows we will assign

The numerical procedure is a shooting method, where we integrate the system of ODEs

with initial conditions

to some ending arc-length

which say that the configuration satisfies the volume constraint and the force balance condition as well as the need for the fluid interface to extend to the wall of the container with the prescribed contact angle.

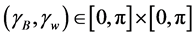

The parameters

This leads to a solution of the initial value problem where we can evaluate the conditions (8)-(11). We use Matlab’s fsolve to then vary

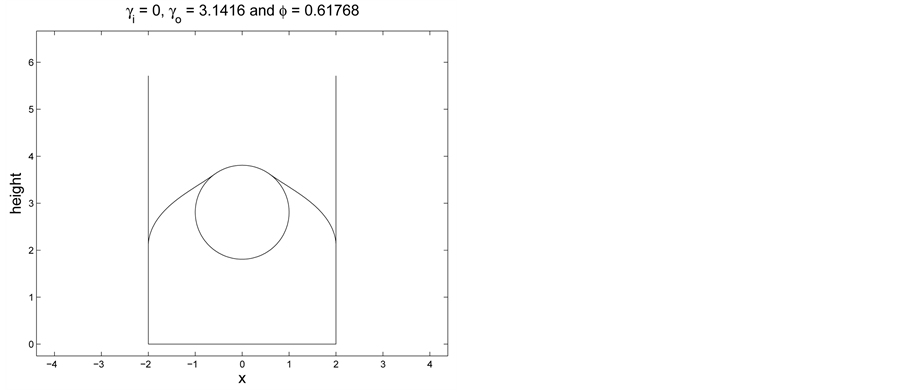

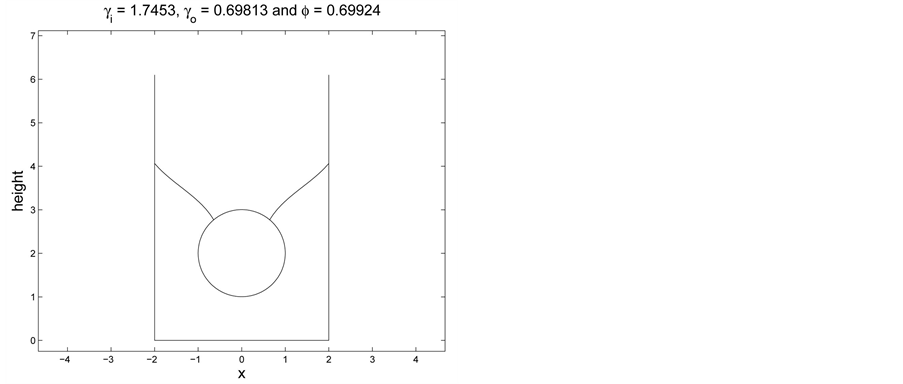

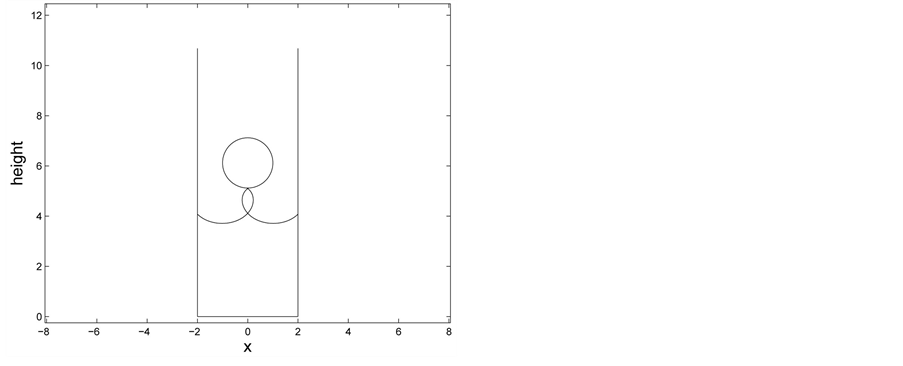

We next proceed with a few examples. In Figure 1 we set

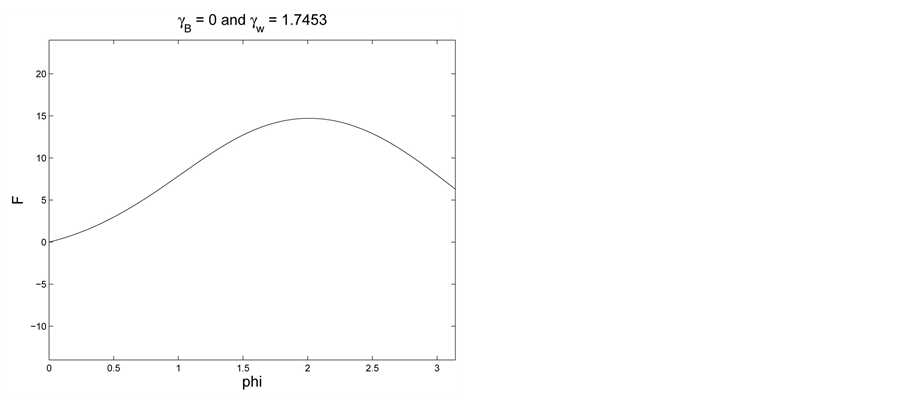

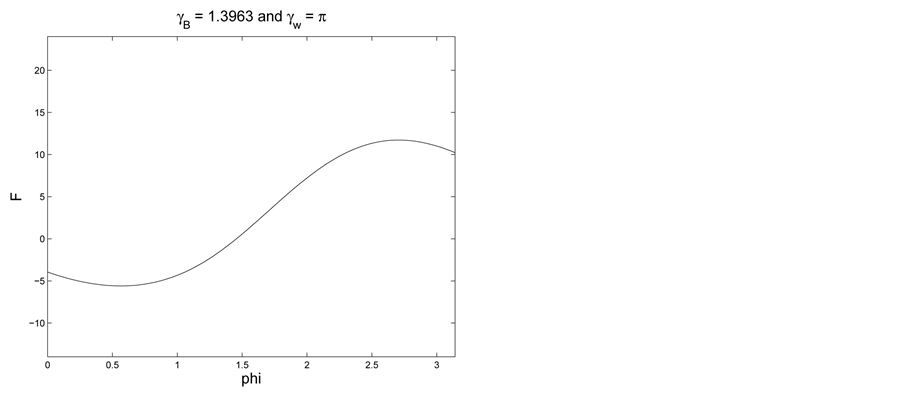

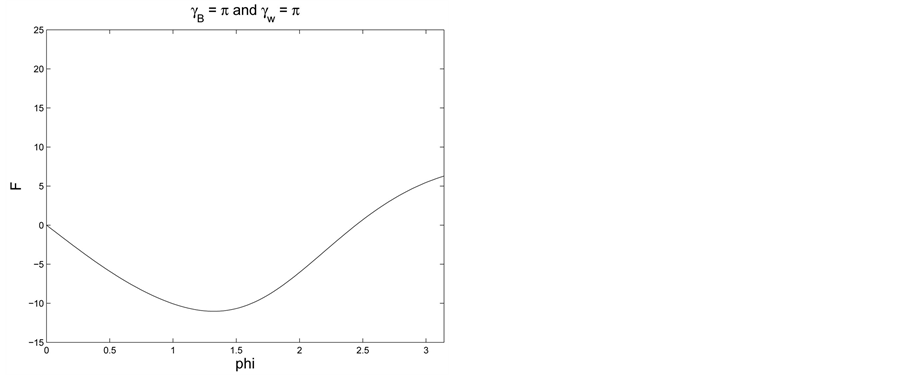

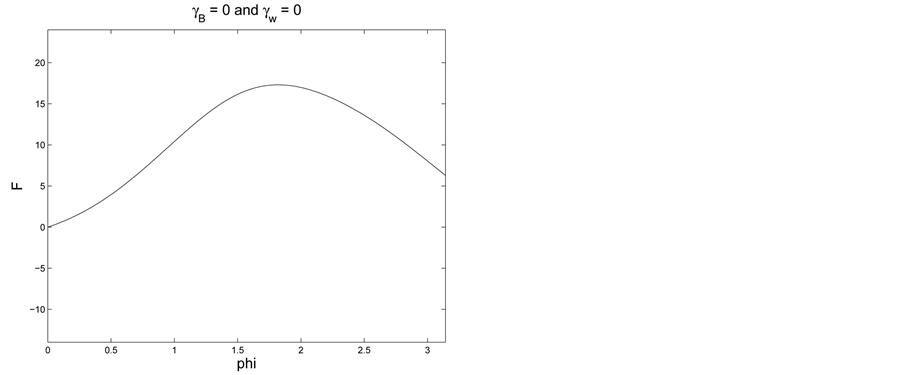

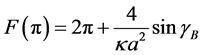

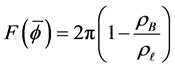

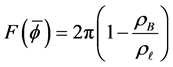

As an approach to explain the behavior in the examples in the second pair, we turn to a study of the function

Figure 1. Comparing contact angles

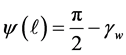

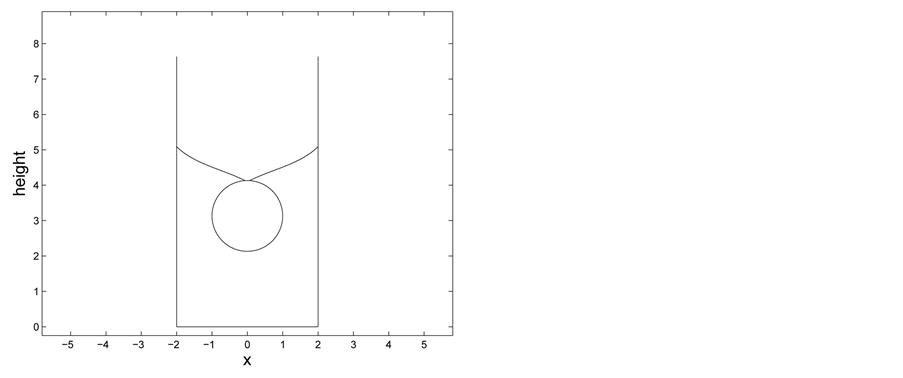

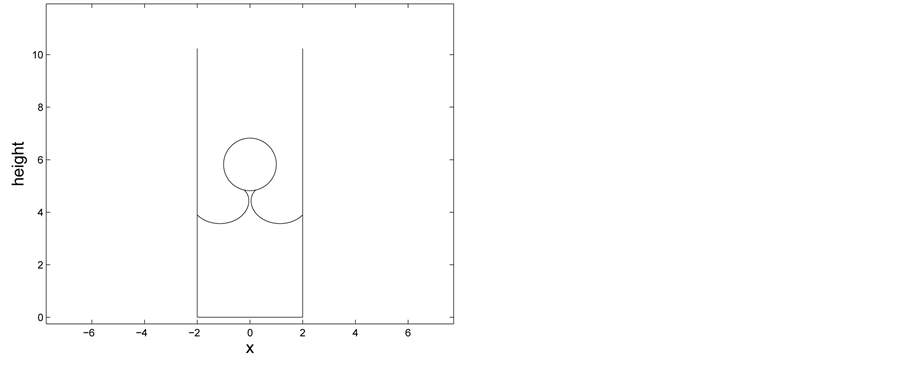

Figure 2. Non-uniqueness: two values of

and we use Matlab’s fsolve to then vary

We do not attempt to evaluate

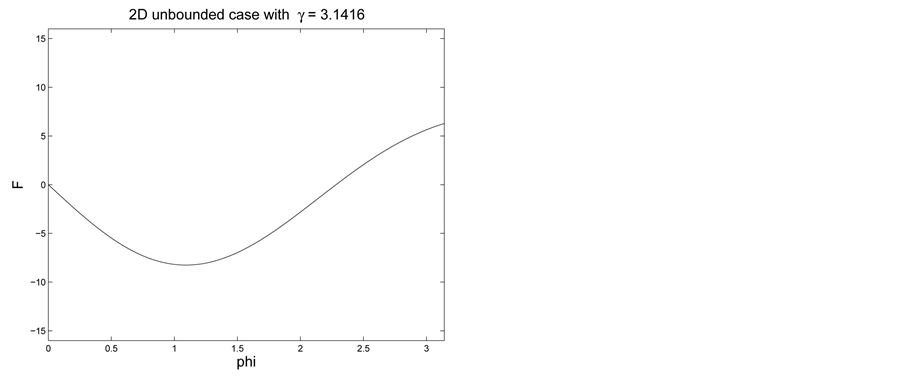

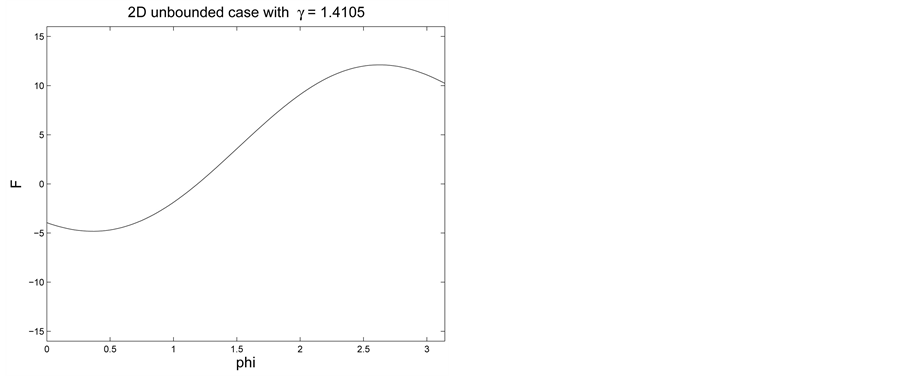

We show the plot of F for

With these solutions to the partial floating ball in hand, we are able to numerically calculate the energy of the configuration. It is simpler to use the scaled mathematical energy

energies are also trivial to compute:

The gravitational potential energy of the liquid is more convenient to compute in sections. First we will treat the portion directly below the interface, but due to the lack of a closed form expression and also due to the variable step size of the data we do this numerically with the trapezoid rule:

Figure 3. Computing partial solutions for values of

Figure 4. Computing partial solutions for values of

Figure 5. Symmetric values of contact angles.

Figure 6. At the extreme range of

where

where h is the maximum step size taken in the irregularly spaced data, and

The case where

which matches (15) upon subtracting

2.2. Unbounded Container in R2

We next consider the unbounded container problem in

that satisfies

satisfying

See [10] and [9] .

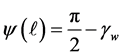

We proceed to the full problem of computing the floating ball configuration in the unbounded

with inclination angle

with

Our results can be compared to Bhatnagar and Finn [10] , where an independent variational formulation was used. In our case, we are formally applying the results from [1] which assumed a bounded container in order to measure the energy of the configuration, whereas in [10] their variational argument was constructed with care to account for the difficulties of infinitesimal variations of infinite quantities.

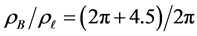

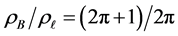

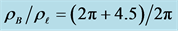

Our examples use

Figure 7. Non-uniqueness: two values of

Figure 8. Unique solution with the same contact angle and

3. Results and Discussion

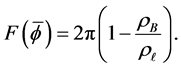

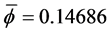

We begin here with the floating ball in a bounded container, and we ask the following question: what values of

It should be stated that while this current work focuses more directly on the influence of the contact angles on the nonuniqueness criterion, the influence of R and a on the nonuniqueness criterion is just as important. To see this impact, compare Figure 9 with Figure 10. We leave a separate study focusing on fixed contact angles and varied values of R and a for a further work.

With the energy computed as in Section 2.1, we first use it in conjunction with the graph of

plotted with that of

Then the energy is computed with this value of

Figure 9. Non-uniqueness of equilibria for

Figure 10. Non-uniqueness of equilibria for

Figure 11. Using the function F to determine which solution has the lower energy. The curves are F and the energy. The lower horizontal line fixes a height that picks up two values of

the smaller value of

We then included the above analysis into the program that generated Figure 9 with a 50 × 50 grid of values for

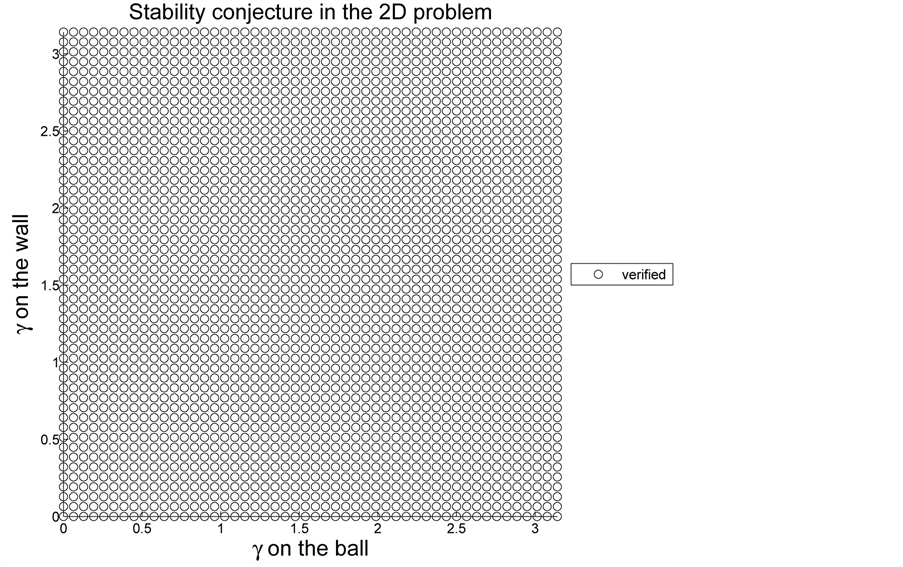

Next, we trace the energy values from a sampling of balls with given, fixed densities as the semi-equilibrium are computed through the range

Figure 12. The light ball energy comparison.

Figure 13. The heavy ball energy comparison.

Figure 14. Verifying the conjecture with

Table 1. The configurations where the conjecture was tested, with the displayed radius a and the half-container width R. Each entry on this table represents 250,000 configurations with 50 × 50 evenly spaced points of

examined. Here we fix a few densities and in contrast, in the previous discussions the densities would vary with the value of

Figure 15. Given 5 sample densities

be a discontinuous change in d. Then we move through the parameter

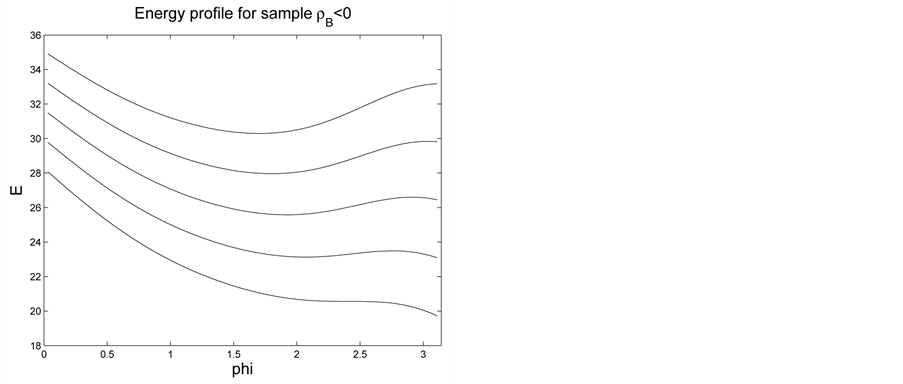

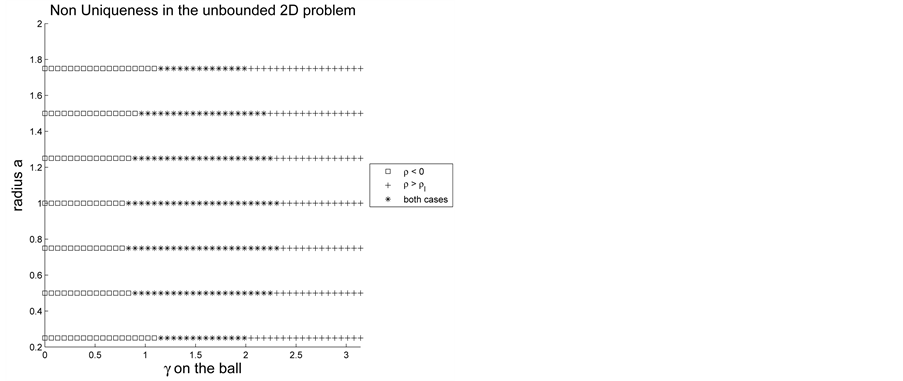

Finally, we turn to a study of

Figure 16 shows the results for

We compute F over

Figure 16.

Figure 17. An example of

Figure 18. Nonuniqueness of equilibria with

rigorous stability analysis. The results from this section then can be seen as purely an analysis of the non- uniqueness criteria.

Conjecture 1. The centrally located floating ball has at most two equilibria in a bounded container in 2D, and the centrally located floating ball has at most two equilibria in the unbounded configuration in 2D. In both cases, this will occur at some value or values of the azimuthal angle

4. Conclusion

We have developed a robust numerical solver for finding the equilibria of a centrally located floating ball in both bounded and unbounded problems in

Cite this paper

Ray Treinen, (2016) Examples of Non-Uniqueness of the Equilibrium States for a Floating Ball. Advances in Materials Physics and Chemistry,06,177-194. doi: 10.4236/ampc.2016.67019

References

- 1. McCuan, J. and Treinen, R. (2013) Capillarity and Archimedes’ Principle of Flotation. Pacific Journal of Mathematics, 265, 123-150.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2140/pjm.2013.265.123 - 2. McCuan, J. (2007) A Variational Formula for Floating Bodies. Pacific Journal of Mathematics, 231, 167-191.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2140/pjm.2007.231.167 - 3. Finn, R. (1986) Equilibrium Capillary Surfaces. Grundlehren der Mathematischen Wissenschaften [Fundamental Principles of Mathematical Sciences], Vol. 284, Springer-Verlag, New York.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4613-8584-4 - 4. Aspley, A., He, C. and McCuan, J. (2015) Force Profiles for Parallel Plates Partially Immersed in a Liquid Bath. Journal of Mathematical Fluid Mechanics, 17, 87-102.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00021-014-0192-3 - 5. Euler, L. (1744) Methodus inveniendi lineas curvas maximi minimive pro-preitate gaudentes, sive solutio problematic isoperimetrici lattisimo sensu accpti. Ser. I, vol. 24, Bousquet, Lausannae et Genevae, E65A. O.O.

- 6. Giaquinta, M. and Hildebrandt, S. (1996) Calculus of Variations, I. Grundlehren der Mathematischen Wissenschaften [Fundamental Principles of Mathematical Sciences], Vol. 310, Springer-Verlag, Berlin.

- 7. McCuan, J. (2013) Extremities of Stability for Pendant Drops, Geometric Analysis, Mathematical Relativity, and Nonlinear Partial Differential Equations. Contemporary Mathematics, 599, 157-173.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1090/conm/599/11944 - 8. Mccuan, J. (2015) New Geometric Estimates for Euler Elastica. JEPE, 1, 387-402.

- 9. Wente, H.C. (2006) New Exotic Containers. Pacific Journal of Mathematics, 224, 379-398.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2140/pjm.2006.224.379 - 10. Bhatnagar, R. and Finn, R. (2006) Equilibrium Configurations of an Infinite Cylinder in an Unbounded Fluid. Physics of Fluids, 18, Article ID: 047103.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.2185661 - 11. Bemelmans, J., Galdi, G.P. and Kyed, M. (2014) Capillary Surfaces and Floating Bodies. Annali di Matematica Pura ed Applicata, 193, 1185-1200.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10231-013-0323-0 - 12. Finn, R. (2006) The Contact Angle In Capillarity. Physics of Fluids, 18, Article ID: 047102.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.2185655 - 13. Finn, R. (2009) Floating Bodies Subject to Capillary Attractions. Journal of Mathematical Fluid Mechanics, 11, 443-458.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00021-008-0268-z - 14. Finn, R. (2011) Criteria for Floating I. Journal of Mathematical Fluid Mechanics, 13, 103-115.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00021-009-0009-y - 15. Finn, R., McCuan, J. and Wente, H.C. (2012) Thomas Young’s Surface Tension Diagram: Its History, Legacy, and Irreconcilabilities. Journal of Mathematical Fluid Mechanics, 14, 445-453.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00021-011-0079-5 - 16. Finn, R. and Sloss, M. (2009) Floating Bodies in Neutral Equilibrium. Journal of Mathematical Fluid Mechanics, 11, 459-463.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00021-008-0269-y - 17. Finn, R. and Thomas, I. (2009) Vogel, Floating Criteria in Three Dimensions. Analysis (Munich), 29, 387-402.

- 18. Kemp, T.M. and Siegel, D. (2011) Floating Bodies in Two Dimensions without Gravity. Physics of Fluids, 23, Article ID: 043303.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.3565779 - 19. Vella, D. (2015) Floating versus Sinking. Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics, 47, 115-135.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev-fluid-010814-014627 - 20. Vella, D. and Mahadevan, L. (2005) The “Cheerios Effect”. American Journal of Physics, 73, 817-825.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1119/1.1898523 - 21. Vella, D., Lee, D.-G. and Kim, H.-Y. (2006) Sinking of a Horizontal Cylinder. Langmuir, 22, 2972-2974.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/la0533260 - 22. Vella, D., Metcalfe, P.D. and Whittaker, R.J. (2006) Equilibrium Conditions for the Floating of Multiple Interfacial Objects. Journal of Fluid Mechanics, 549, 215-224.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/s0022112005008013 - 23. Whitesides, G.M. and Boncheva, M. (2002) Beyond Molecules: Self-Assembly of Mesoscopic and Macroscopic Components. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 99, 4769-4774.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.082065899 - 24. Whitesides, G.M. and Boncheva, M. (2002) Self-Assembly at All Scales. Science, 295, 2418-2421.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1070821 - 25. Binks, B.P. and Horozov, T.S. (2006) Colloidal Particles at Liquid Interfaces: An Introduction. In: Binks, B.P. and Horozov, T.S., Eds., Colloidal Particles at Liquid Interfaces, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1-74.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511536670.002 - 26. Tavacoli, J.W., Katgert, G., Kim, E.G., Cates, M.E. and Clegg, P.S. (2012) Size Limit for Particle-Stabilized Emulsion Droplets under Gravity. Physical Review Letters, 108, Article ID: 268306.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.108.268306 - 27. Bush, J.W.M. and Hu, D.L. (2006) Walking on Water: Biolocomotion at the Interface. Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics, 38, 339-369.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.fluid.38.050304.092157 - 28. Gao, X. and Jiang, L. (2004) Water-Repellent Legs of Water Striders. Nature, 432, 36.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/432036a - 29. Hu, D.L., Chan, B. and Bush, J.W.M. (2003) The Hydrodynamics of Water Strider Locomotion. Nature, 424, 663-666.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature01793 - 30. Ozcan, O., Wang, H., Taylor, J.D. and Sitti, M. (2010) Surface Tension Driven Water Strider Robot Using Circular Footpads. IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Anchorage, 3-7 May 2010, 3799-3804.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/robot.2010.5509843 - 31. Song, Y.S. and Sitti, M. (2007) Surface-Tension-Driven Biologically Inspired Water Strider Robots: Theory and Experiments. IEEE Transactions on Robotics, 23, 578-589.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/TRO.2007.895075