Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

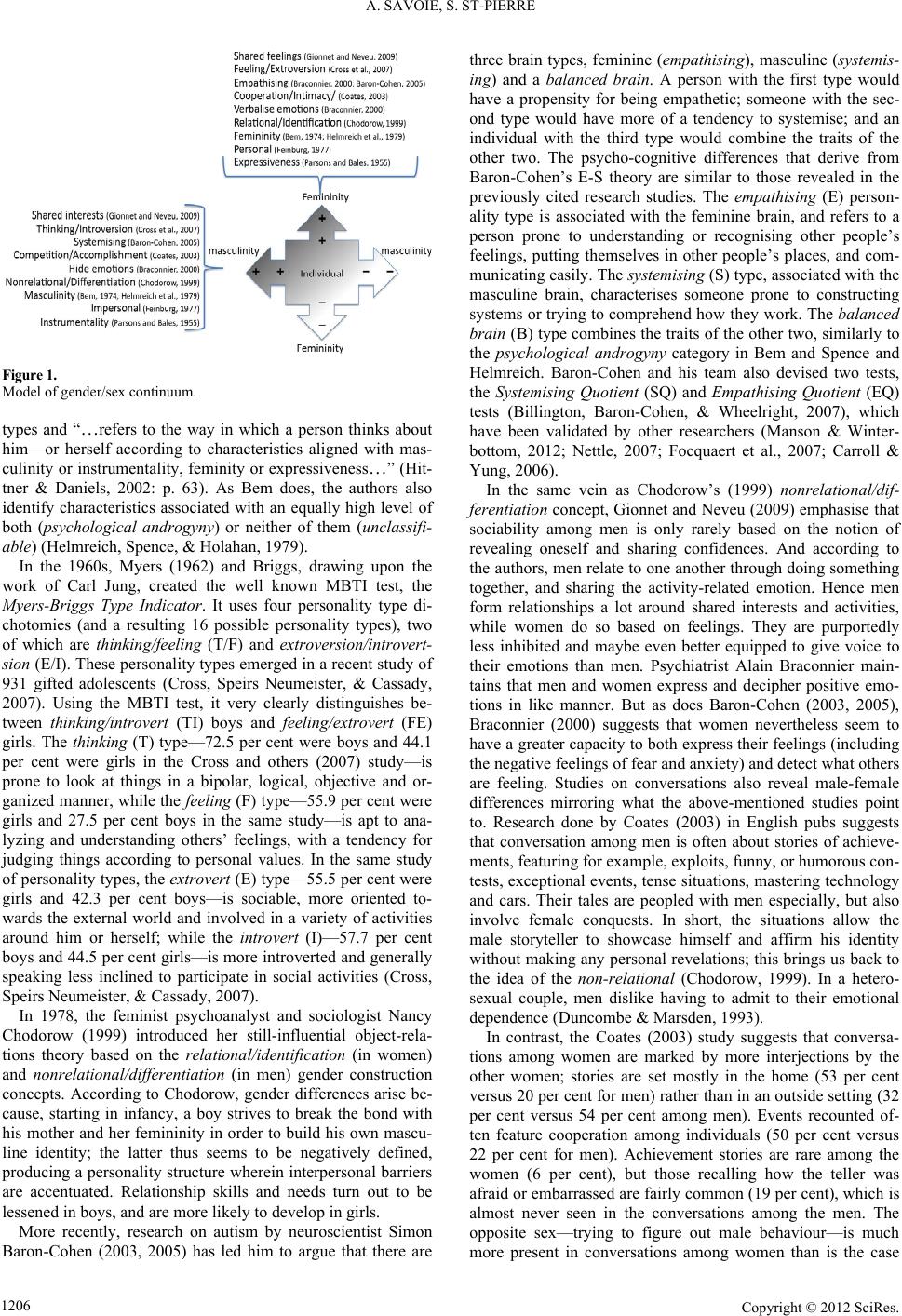

Creative Education 2012. Vol.3, No.7, 1205-1211 Published Online November 2012 in SciRes (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/ce) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ce.2012.37179 Copyright © 2012 SciRe s . 1205 Gender-Differentiated Behaviour Traits of Elementary School Pupils in Identical Visual Arts Learning Situations Alain Savoie, Sylvie St-Pierre Faculty of Education, Université de Sherbrooke, Sherbrooke, Can ad a Email: alain.savoie@usherbrooke.ca Received August 2nd, 2012; r evised September 11th, 2012; accepted September 24th, 2012 This exploratory qualitative research project comparatively observes the conduct of girls and boys—in their third year of elementary school—divided in same-gender dyads, participating successively in an identical visual arts project in Canada. Our goal is to improve knowledge of the differences and similari- ties between boys and girls in a learning situation and help to devise gender-differentiated teaching strate- gies in the visual arts, a curricular subject for which boys typically show limited interest. We categorize the behaviour patterns of our research subjects according to a behavioural indicators table we designed after reviewing literature on female/male brain, personality types, gender and gender role. We observe notable gender differences in behaviour among the pupils, with “male indicators” overwhelming identified in the boys and, surprisingly, in one girl, while the “female indicators” are clearly dominant in the other girls. Keywords: Elementary School; Visual Arts Education; Gender; Gender Role; Differentiated Instruction; Behavioural Indicators Gender-Differentiated Instruction Our exploratory research study aims to identify and describe some cognitive, psychological and socio-cultural characteristics of boys and girls in a visual arts learning situation. From then on, our teaching strategies will be a function of differentiated arts instruction and based on the variability deriving from the identified gender-related behaviours in learning situations. Dif- ferentiated instruction applies in a context of cultural and cog- nitive heterogeneousness among pupils, and is structured ac- cording to the characteristics of the latter’s diversity (Per- raudeau, 1997; Przesmycki, 2004; Astolfi, 2004). As Perrenoud (1995: p. 28) suggests, “A didactic situation uniformly pro- posed to or imposed on a group of pupils is inevitably unsatis- factory for some of them”. Research on arts instruction carried out in Quebec and elsewhere in the West, suggests that boys show less personal involvement in the arts fields; in other words, they are less interested in the artistic disciplines than girls, and are generally less suc cessful in art, except at the level of graduate studies. Few of them envisage embarking on a ca- reer in the arts, and they participate less in cultural activities (ISQ, 2007; Savoie, 2008, 2009; Savoie, Grenon, & St-Pierre, 2010; Octobre, 2004; Dumais, 2002; Blaikie, Schönau, & Steer s, 2003). From this stems our hypothesis that many art-related teaching situations—starting from when pupils are youngest— could be better adapted to boys. Documented Differences between Boys and Girls Most studies generally use self-reported tests to assess adult gender role orientation. Somehow, this method is difficult to apply to young children. This is why we preferably choose to observe and describe the behavioural dimension of genders in our study. “Behaviour is a biological organism’s response to a situation, an environment or even its own internal stimuli. Therefore, individually or collectively, behaviours may be cau- sed or regulated by multiple internal or external situations af- fecting individuals (Monteil, 2008: p. 82).” They may be de- scribed as all the individual’s actions and reactions in a particu- lar context or situation. By stabilizing and controlling, where possible, the external context or environment shared by several individuals, we can, through their behaviour patterns, under- stand the internal context at play. The internal context is shaped by cognitive structures, meaning mental processes such as thought, memory, attention, learning, attitudes, perceptions and even emotions (Blakemore & Frith, 2005). There are multiple determining factors and behavioural mechanisms, and no field of study can alone cover them all (Monteil, 2008). Hence, for our qualitative study, we reviewed the scientific literature on gender, gender role, male/female brain and personality types— including cognitive, psychological and socio-cultural charac- teristics most frequently overlapping in research studies—in order to draw up our own behaviour indicators analysis table. Note that all these studies place gender traits in a blended con- tinuum rather than at completely opposite ends of a spectrum (Figure 1). During the 1950s, Parsons and Bales created the instrumen- tality (masculine) and expressiveness (feminine) scales (Helm- reich, Spence, & Holahan, 1979). In the 1970s, feminist psy- chologist Sandra L. Bem (1974) invented the Bem Sex Role Inventory (BSRI), a self-reported perceptions test. Items are rated on a masculine, feminine, and non-gender-related scale, implying that individuals perceive themselves along a contin- uum of sexual roles (social desirability). According to Bem, a person identifying highly as well as equally with masculine and feminine characteristics is linked to the psychological androg- yny classification. Another self-reported perceptions test is the Personal Attributes Questionnaire (PAQ) by Spence, Helm- reich and Stapp. Similarly to the BSRI, it employs gender role  A. SAVOIE, S. ST-PIERRE Figure 1. Model of gender/sex continuum. types and “…refers to the way in which a person thinks about him—or herself according to characteristics aligned with mas- culinity or instrumentality, feminity or expressiveness…” (Hit- tner & Daniels, 2002: p. 63). As Bem does, the authors also identify characteristics associated with an equally high level of both (psychological androgyny) or neither of them (unclassifi- able) (Helmreich, Spence, & Holahan, 1979). In the 1960s, Myers (1962) and Briggs, drawing upon the work of Carl Jung, created the well known MBTI test, the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator. It uses four personality type di- chotomies (and a resulting 16 possible personality types), two of which are thinking/feeling (T/F) and extroversion/introvert- sion (E/I). These personality types emerged in a recent study of 931 gifted adolescents (Cross, Speirs Neumeister, & Cassady, 2007). Using the MBTI test, it very clearly distinguishes be- tween thinking/introvert (TI) boys and feeling/extrovert (FE) girls. The thinking (T) type—72.5 per cent were boys and 44.1 per cent were girls in the Cross and others (2007) study—is prone to look at things in a bipolar, logical, objective and or- ganized manner, while the feeling (F) type—55.9 per cent were girls and 27.5 per cent boys in the same study—is apt to ana- lyzing and understanding others’ feelings, with a tendency for judging things according to personal values. In the same study of personality types, the extrovert (E) type—55.5 per cent were girls and 42.3 per cent boys—is sociable, more oriented to- wards the external world and involved in a variety of activities around him or herself; while the introvert (I)—57.7 per cent boys a nd 44.5 per cent girls— is more int roverted a nd general ly speaking less inclined to participate in social activities (Cross, Speirs Neumeister, & Cassady, 2007). In 1978, the feminist psychoanalyst and sociologist Nancy Chodorow (1999) introduced her still-influential object-rela- tions theory based on the relational/identification (in women) and nonrelational/differentiation (in men) gender construction concepts. According to Chodorow, gender differences arise be- cause, starting in infancy, a boy strives to break the bond with his mother and her femininity in order to build his own mascu- line identity; the latter thus seems to be negatively defined, producing a personality structure wherein interpersonal barriers are accentuated. Relationship skills and needs turn out to be lessened in boys, and are more likely to develop in gi rls. More recently, research on autism by neuroscientist Simon Baron-Cohen (2003, 2005) has led him to argue that there are three brain types, feminine (empathising), masculine (systemis- ing) and a balanced brain. A person with the first type would have a propensity for being empathetic; someone with the sec- ond type would have more of a tendency to systemise; and an individual with the third type would combine the traits of the other two. The psycho-cognitive differences that derive from Baron-Cohen’s E-S theory are similar to those revealed in the previously cited research studies. The empathising (E) person- ality type is associated with the feminine brain, and refers to a person prone to understanding or recognising other people’s feelings, putting themselves in other people’s places, and com- municating easily. The systemising (S) type, associated with the masculine brain, characterises someone prone to constructing systems or trying to comprehend how they work. The balanced brain (B) type combines the traits of the other two, similarly to the psychological androgyny category in Bem and Spence and Helmreich. Baron-Cohen and his team also devised two tests, the Systemising Quotient (SQ) and Empathising Quotient (EQ) tests (Billington, Baron-Cohen, & Wheelright, 2007), which have been validated by other researchers (Manson & Winter- bottom, 2012; Nettle, 2007; Focquaert et al., 2007; Carroll & Yung, 2006). In the same vein as Chodorow’s (1999) nonrelational/dif- ferentiation concept, Gionnet and Neveu (2009) emphasise that sociability among men is only rarely based on the notion of revealing oneself and sharing confidences. And according to the authors, men relate to one another through doing something together, and sharing the activity-related emotion. Hence men form relationships a lot around shared interests and activities, while women do so based on feelings. They are purportedly less inhibited and maybe even better equipped to give voice to their emotions than men. Psychiatrist Alain Braconnier main- tains that men and women express and decipher positive emo- tions in like manner. But as does Baron-Cohen (2003, 2005), Braconnier (2000) suggests that women nevertheless seem to have a greater capacity to both express their feelings (including the negative feelings of fear and anxiety) and detect what others are feeling. Studies on conversations also reveal male-female differences mirroring what the above-mentioned studies point to. Research done by Coates (2003) in English pubs suggests that conversation among men is often about stories of achieve- ments, featuring for example, exploits, funny, or humorous con- tests, exceptional events, tense situations, mastering technology and cars. Their tales are peopled with men especially, but also involve female conquests. In short, the situations allow the male storyteller to showcase himself and affirm his identity without making any personal revelations; this brings us back to the idea of the non-relational (Chodorow, 1999). In a hetero- sexual couple, men dislike having to admit to their emotional dependence (Duncombe & Marsden, 1993). In contrast, the Coates (2003) study suggests that conversa- tions among women are marked by more interjections by the other women; stories are set mostly in the home (53 per cent versus 20 per cent for men) rather than in an outside setting (32 per cent versus 54 per cent among men). Events recounted of- ten feature cooperation among individuals (50 per cent versus 22 per cent for men). Achievement stories are rare among the women (6 per cent), but those recalling how the teller was afraid or embarrassed are fairly common (19 per cent), which is almost never seen in the conversations among the men. The opposite sex—trying to figure out male behaviour—is much more present in conversations among women than is the case Copyright © 2012 SciR es . 1206  A. SAVOIE, S. ST-PIERRE with conversations among men. Self-revelation and wanting to empathize with the other are also more pronounced in women chatting among themselves. Differences between Girls’ and Boys’ Drawings Few research studies focus on the differences in behaviour among boys and girls in the visual arts, as we do in the present study involving a school creative project. To our knowledge, no study has employed a theoretical framework encompassing the previously reviewed concepts relating to masculinity and femi- ninity. Note, however, that feminist studies have resulted in a large body of psycho-sociological research comparing gender and sex in visual arts instruction. Among other things, they have shown that sexist attitudes existed in teaching methods, and have contributed to changing attitudes in the academic discipline (Garber et al., 2007). Another kind of research study discriminating according to gender in arts instruction has also focused on unsolicited draw- ings by children. Since the beginning of the twentieth century, scores of research projects have compared the artistic output of boys and girls of all ages. This has resulted in a considerable amount of data, the analyses of which point to significant, re- curring gender-determined differences in the drawings done, regardless of culture (Kellog, 1967; Feinburg, 1977; McNiff, 1982; Flannery & Watson, 1995; Rogers, 1995; Speck, 1995; Chen & Kantner, 1996; Salkind & Salkind, 1997; Duncum, 1997; Tuman, 1999, 2000; Golomb, 2004). Comparative analy- ses of freehand drawings by boys and girls re veal simila rities to the masculine/feminine traits found in the previously mentioned studies. The common conclusion from research in arts instruc- tion is that boys’ drawings tend to focus on object—and com- petition—related themes, while girls’ drawings deal with peo- ple and human relationships (McNiff, 1982; Chen & Kantner, 1996; Feinburg, 1977; Flannery & Watson, 1995; Rogers, 1995; Salkind & Salkind, 1997; Speck, 1995). Girls’ drawings espe- cially emphasize colours, attention to aesthetics, the detailed il- lustrations of people (women in particular), plants, placid ani- mals such as horses, and family scenes in the home. Boys’ drawings more often feature scenes of action and violence, suspense, danger, weapons, rescue operations, etc. They also show a preference for machines, monsters, dinosaurs and mas- culine characters (Kellog, 1967; Feinburg, 1977; McGuiness, 1979; Wilson & Wilson, 1982; McNiff, 1982). A US study by Feinburg (1977) involving 180 children, shows differences in boys’ and girl’s drawings when two themes, “fight” and “care” were specified for a visual arts project; boys drew scenes of power and impersonal skills (involving for example, the army, rules and order) while girls illustrated more personal conflicts, more often a scene with two people who are their friends or relatives. In short, girls revealed an intimate side and personal feelings, while boys focused on accomplishments, exploits, and mastery, all reflecting the traits suggested by the previously cited studies with adults. To what extent do infants’ drawings reflect the influence or even pressure of their peers or what they feel their teacher ex- pects of them based on their gender? This is an aspect that must be considered. For example, according to Thorne (1993), where children’s games are concerned, typically masculine or femi- nine behaviour exist, and she theorizes that children exert social pressure (using derision) among themselves to conform to these gendered behaviour characteristics. This induces us to support the idea that innate and acquired dimensions of differences among genders/sexes are interwoven. The goal of our research, however, is not to distinguish the innate from the acquired in children’s behaviours, but only to comparatively observe how they manifest themselves in boys and girls placed in identical visual art learning situations. To summarise—inspired by the scales of Baron-Cohen (2005: p. 24) and Norlander and Erixon (2000: p. 427)—Figure 1 is the model we devised showing the main masculine and femi- nine traits identified in the above-cited studies. This model is construed as a continuum where femininity and masculinity co- habit or are interwoven to highly varying degrees from one in- dividual to another, thus making each person unique. Methodology Participants Four boys and four girls, each eight years old, in their third year of elementary school (in the Montreal, Canada region) took part in our exploratory qualitative study in the visual arts field. It was not our intent to place the study in an ecological context, as the eight pupils were subjected to our same-gender dyad experiment after regular classroom hours. The two pupils in each group had to collaborate with each other, but each cre- ated his/her own final artwork. The four dyads—two male and two female—therefore successively did the same activity, each pupil ending up alone with the two researchers, one of whom was the pupil’s regular teacher. The latter instructed the work of each dyad in the same way. The other researcher was respon- sible for video-recording the entire instruction process, inter- vening only negligibly in the creative activity. Each of the four experimental situations lasted for about 45 minutes (in a single session), even though no time limit was imposed on the chil- dren. The test subjects’ availability and logistical constraints meant that data collection was spread out over eighteen weeks. Task and Procedure Our activity made no pretence about being neutral, and in fact it was meant to be attractive to the boys. The learning si- tuation the children were given was “Mr. Calder and sports”. It was divided into three stages, following the creative process recommended in the Quebec Education Program (MEQ, 2001). Stage I—Inspiration First of all, the teacher-researcher told the two pupils about the American sculptor Alexander Calder, his work and his technique of using metal wire to create three-dimensional fig- ures—human and animal. The children looked through books on Calder and his work, gave their opinions freely, stimulated by the many illustrations and the questions they were asked about these. Once the children had been familiarised with the sculptor’s world, the theme of sports was proposed to them. They were shown images of athletes in different sports. The children could again freely express themselves, this time on the theme of sports, following our questions about the athletes’ photos and about their favourite sports. A pupil was then asked to stand and mimic the actions of an athlete in motion, and to hold a pose while his/her teammate made three pencil sketches of the pupil—mimicking the athlete—in three successive, dif- ferent poses. Then the roles were reversed. After this the pupils returned to their place at a large table, and in the final step of the inspiration stage, in a semi-directed interview, they were Copyright © 2012 SciRe s . 1207  A. SAVOIE, S. ST-PIERRE Copyright © 2012 SciRe s . 1208 asked in turn to visualise and talk about a sports figure. Stage II—Development The children then had to create a sporting figure, with Alex- ander Calder’s works as inspiration and using—as he did— metal wire, a length of which the pupils were given. The tea- cher-researcher explained a few safety rules, following which the pupils practiced handling the wire and getting used to the material. They then created their own figures. Stage III—Focus Once they finished their artwork, the pupils, in a final semi- directed interview, had to talk about how they went about their creative process, making the connection between the figure they examined at the beginning of the exercise and the one they ended up making with metal wire. Analysis Tool Based on the literature review discussed in detail above, we devised two analysis categories that form a continuum (Figure 1), which we labelled F+ and M+. The first one, derived from the research results consulted, refers to behaviour traits mostly associated with females, and the second refers to those traits mostly associated with males. Our F+ category includes 70 items or indicators, in the form of notions and keywords taken from our conceptual framework; Category M+ has 66 indica- tors (Table 1). The data collected (video recordings) allowed us to analyze the eight subjects’ behaviour and explanations, coded to corre- spond to our indicators. The two researchers—a man and a woman—screened the eight videos recorded; behaviour traits were coded by the woman researcher, and subsequently vali- dated by the male researcher, thereby producing a coding con- sensus using the NVivo™ software application. Data on verbal expression was collected not only while the pupils talked as they worked on their own, but also during the four semi-di- rected interviews they were subjected to. Results and Discussion Analyzing the videos, we came up with a total of 243 behav- iour traits for the eight pupils, and they were assigned a code from Category F+ or M+. For example, a Category F+ (Table 1) behaviour trait is seen in Stage I (Inspiration); the teacher-re- searcher displays illustrations of Alexander Calder and asks Girl #5 “What does the image you are looking at make you think of?” The girl replies “Leaves on a tree”, while smiling and turning her head from left to right, simultaneously negating her answer to leave room for other possible interpretations of the image. This is evidence of Indicator 17, “Leave room for dif- ferent interpretations”, from Category F+ (Table 2). Another answer—by Boy #4—points this time to a Category M+ (Table 1) behaviour trait. The teacher-researcher asks the Table 1. F+ and M+ indicators. Category F+ (“femini ne” behaviour traits/indicators) Category M+: (“male” behaviour tr aits/indic at ors) Attitude/mood 1) Ask how the other perso n feels; 2) Interac t without hurting; 3) Make demands softly; 4) Care ab ou t t he other person’s needs; 5) Devote oneself; 6) Refer to the other’s feelings while clearly statin g one’s own; 7) Reciprocity in dialogue, liste n o bviously; 8) Perceive the other person’s emotions; 9) Deciphe r t he emotional atmosphere between people; 10) Eye contact; 11) Social smile; 12) Read othe rs’ thought s; 13) Know and s elect a m ore appropriate gesture to make; 14) Predict the other’s behaviour and mood; 15) Concern for justice a nd fairness; 16) Figure out non-verbal communication; 17) Leave room for different interpretations; 18) Entertaining games, flexible rules; 19) Consultation, cooperation; 20) Self depreca tin g ; 21) Hesitation, prudenc e; 22) Avoid confrontation allow the other to save face; 23) Reserved enthusiasm; 24) Calmn ess, tranquili t y; 25) Extroversion; 26) Will identify with… 27) Personalisa ti on. 1) Technical systems; 2) Natural systems; 3) Abstract systems; 4) Social systems; 5) Psychological systems 6) Organizational systems; 7) Motor, kinaesthetic systems; 8) Activity for its own sa ke; 9) Analysis of data and characteristics; 10) Attention to details; 11) Logical; 12) Hierarchical; 13) Interested in handling tools and objects; 14) Handle ob j ects systematically; 15) Group games based on rules; 16) Self assurance, be in control; 17) Strength in solitude; the lone super hero; 18) Audac i o us, fearless, adventure; 19) Group solid arity; 20) Keep emotions in check, remain “cool”; 21) Enthusiasm and impetuousness; 22) Dominance and valorisation of power; 23) Importance of soc ial standing; 24) Introversi on; 25) Stand out; 26) Independe nc e; 27) Prefer the impersonal; 28) Move ar ound, be active; Ways of communicating 28) Focus on what the other says; 29) Treat the other as an equal; 30) Make sur e the other knows how things are going; 31) Seek intimacy (reveal one’s secrets); 32) Express disagreement with a que stion, criticise tactfully; 33) Express attentiveness a n d understanding. 34) Take offe nse bearing in mind the other’s experiences; 35) Openness towards the other and aptitude for taking their perspective; 36) Be motiv ated to find o ut about the other’s experiences; 37) Be receptive to the other person wanting to change the subject. 29) Spend time in a group ; 30) Concise language; 31) Conversations deal with things (objects); 32) Tease and pr etend to be hostile; 33) Use humour.  A. SAVOIE, S. ST-PIERRE Continued Topics of communication 38) Admitting to one’s fe ars and weaknesses; 39) Sharing one’s fe e lings 40) Bring out t he other’s feelings, react; 41) Tales of coo peration among individuals; 34) Share com mon interests: Tales about explo its, self promotion; 35) Competition; 36) Talk about mastering technologies, situations; 37) Female conq uest ; 38) Topics that preserve one’s privacy; 39) Display knowledge; Management style 42) Consultative; 43) Inclusive; 44) Collaborative (consensus seeking); 45) Dominati on frowned on; 46) Propose compromises; 47) Verbal persuasion. 40) Task oriented; 41) Assert power; 42) Impera tive ; 43) Give direct orders; 44) Prohibitio n; 45) Criticise directly; Approach, making conta ct 48) Empathy through looks, gestures, words; 49) Say kind w ords; 50) Charm, appreciation, respect; 51) Mutual compliments about one’s appearance; 52) Sit close to the other; 53) Touch each other; 54) Be jealous; 55) Ignore the other; 56) Repeat gossip; 57) Ridicule; 58) Snub; 59) Manipula t e by flattery or otherwise; 46) Friendly contact in a rough man ner; 47) Ridicule, insult; 48) Take note of slights; reject physical contact; 49) Play at fighting, friendly horseplay; 50) Intimidate ; 51) Confrontational ; Joining a new group 60) Do so with c are, observe w hat’s happening; 61) Make accommodation, make oneself accepted; 62) Offer useful suggestions and comments; 63) Introduce the other person; 64) See if the other wants to join the conversation; 65) Ask wha t t he other thinks of the top ic; 52) Ignore the person trying to join th e group; 53) As a new arrival, ignore the feelings of the group; 54) As the new arrival, take charge of the game, change the group dynamics; 55) Wanting to look tough; 56) Fight, rough up; 57) Indiscreet; 58) Antagonistic; 59) Threaten the others; 60) Judge others’ emoti on s and intentions poorly, be annoying ; Measured skills 66) Localisation and memorising objects; 67) Orientation by refere nces 68) Mathematical calculation; 69) Verbal expression; 70) Fine dexterit y. 61) Visualisation, object rotation; 62) Transfe r from 2D to 3D; 63) Orientation/topography (maps/plans); 64) Maths: problem resolution; 65) Throwing dexterity; subject what inspired him to create a figure representing a hockey goalkeeper. The boy replies: “…anyway I’m a good goalie myself. When I was playing against other grownups, I never let a puck pass me during a whole hour …that’s how the game lasted three periods…the score was two-zero and I was really proud. It wasn’t the first time I did that. I stop goals a lot of times. And if a puck goes in the goal I never get discour- aged. …I tell myself I’ll keep going… and still win. That’s what made me [choose] hockey, because I really like that. [I watch] just about all the games. Plus I really like playing hockey dur- ing the winter.” The answer was assigned Indicator Code #34, “Tales about exploits, self promotion” from Category M+ (Ta- ble 1). The descriptive analysis of the compilation of the indicators for each subject according to our F+ and M+ categories is given in Tables 2 and 3. The coded results for the girls, with the ex- ception of Girl #6, proved to be highly polarised. The same holds true for the boys, a reflection of gendered behaviour traits echoing those discussed in our review of the literature on boy- girl differences. Our results suggest, in fact, that 74 per cent of the boys’ behaviour traits are coded as M+ versus only 29.7 per cent of the girls’ behaviour. Conversely, 70.8 per cent of the girls’ behaviour traits are coded as F+ versus only 25 per cent of the boys’ behaviour. Tables 2 and 3, and Figures 2 and 3 nevertheless show that indicators from the F+ and M+ categories show up in both boys and girls. Category M+ indicators are clearly preponderant in all our male test subjects (Figure 3), and surprisingly in Girl #6. Many more indicators from Category F+ than from Category M+ show up in the other three female test subjects (Figure 2). The extent to which masculine indicators are manifested in the boys (an average of 73.9 per cent) is less than that (an average of 84.5 per cent) to which feminine indicators apply in three of our female test subjects. There is an appreciable percentage— 21.7 per cent to 33.4 per cent—of F+ indicators among the boys, while three girls manifest M+ indicators from 11.8 per cent to 18.7 per cent, with the exception of the fourth female test sub- ject (Girl #6) with 61.1 per cent Category M+ indicators. Our results therefore suggest a clear preponderance of Category F+ indicators among three girls and a very marked presence of Category M+ indicators among the four boys. The unusual predominance of M+ indicators in Girl #6 (Fig- ure 3) may seem surprising, but is in concordance with the theories revealed in our literature review. This atypical varia- tion indicates to us that ultimately we all are unique, and no individual can be reductively stereotyped according to that individual’s gender; masculine and feminine traits coexist in every person. The results for Girl #6 tend toward a balance between female and male indicators, which takes us back to the theory of psychological androgyny put forward by Bem (1974) and Spence, Helmreich and Stapp (Helmreich, Spence, & Hola- han, 1979), as well as that of the balanced brain suggested by Baron-Cohen (2003, 2005). The latter asserts that 40 percent of women have a feminine brain, 20 per cent a masculine brain Copyright © 2012 SciRe s . 1209  A. SAVOIE, S. ST-PIERRE Table 2. Percentage of F+ and M+ indicators showing for each female research subject. Girl #5 Girl #6 Girl #7 Girl #8 6M+: 18.7% 22M+: 61.1 % 3M+: 16.6% 4M+: 11.8% 26F+: 81.3% 14F+: 38.9% 15F+: 83.4% 30F+: 88.2% Table 3. Percentage of F+ and M+ indicators showing for each male research subject. Boy #1 Boy #2 Boy #3 Boy #4 33M+: 75% 24M+: 75% 18M+: 78.3% 16M+: 66.% 11F+: 25% 8F+: 25% 5F+: 21.7% 8F+: 33.4% Figure 2. Percentage of F+ indicators manifested in each boy and girl. Figure 3. Percentage of M+ indicators manifested in each boy and girl. and 40 per cent could be said to possess a balanced brain. Incidentally, many studies suggest that individuals linked to the psychological androgyny category are apparently cogni- tively more flexible and would seem to have more highly de- veloped creative artistic tendencies (Stoltzfus et al., 2011; Kel- ler, Lavish, & Brown, 2007; Hittner & Daniels, 2002; Nor- lander & Erixon, 2000). Our test subjects are admittedly much younger than those in most gender role studies, but from studying our video recording we learn that our atypical female test subject, Girl #6, when compared to our other test subjects, rapidly came up with inspiration, created her wire figure with startling ease, and quickly and confidently handled the new material; of all the test subjects’ final work, hers was the most well done and completed one. Near equilibrium in the assigned coding of the F+ and M+ indicators could be a sign of an artis- tic aptitude, and this hypothesis should definitely be more thoroughly investigated in our future research studies. Our results show that, to varying degrees, both female and male psycho-cognitive traits coexist in all our test subjects; however, either the M+ or F+ indicators become preponderant in our male and female subjects’ behaviour traits of when they are placed in a visual arts learning situation. Conclusion Our exploratory research suggests the existence of gender- linked behavioural aspects; our close attention to them will foster a deeper understanding of them in our future research. The preponderance of Category F+ indicators among three of our female test subjects and Category M+ indicators among all our male and one female test subjects points to clearly distin- guishable boy-girl differences; nonetheless these are mitigated by the performance of our atypical Girl #6. There are many factors that cause behaviour, and necessarily choosing an angle from which to study them inevitably limits the scope of the study, nevertheless our analysis chart is still a tool to be maintained and perfected in future research. It became obvious during our data analysis that our subjects being in dyads was a factor influencing their behaviour. In fact, other factors will have to be taken into account in future studies. These of course include the work done, a correlative context, pupil group size, the personalities of the work partners, the children’s ages, their maturity, etc. The behaviour of the tea- cher herself, which influences the pupils, will also have to be observed—her way of asking questions, how strictly she mod- erates each group, the kinds of intervention, how the gender of the children affects her way of leading the activity, etc. Atypi- cal pupils and the concept of psychological androgyny must also be studied from the standpoint of their link to any predis- position toward the arts. These factors comprise a list to be considered in future studies to be done. The knowledge thereby gained will help in implementing instructional tools that not just take into account gender differences in the visual arts, but that also can be applied in all learnin g situations at school. Acknowledgements This research was supported by a grant from the Fonds de recherche société et culture Québec (FQRSC) to Dr. Savoie. We wish to thank Carole Demers, who assisted in the data col- lection and part icipated in this study’s preliminary analyses. REFERENCES Astolfi, J.-P. (20 04 ). L’école pour apprendre. Paris: ESF. Baron-Cohen, S. (2003). The essential diff erence: Male and female b rain and the truth about autism. New York, Basic Books. Baron-Cohen, S. (2005). The essential difference: The male and female brain. Phi Kappa Phi Forum, 85, 23-25. Bem, S. L. (1974). The measurement of psychological androgyny. Jour- nal of Consulting an d C li n ic al Psychology, 42, 155-162. doi:10.1037/h0036215 Billington, J., Baron-Cohen, S., & Wheelright, S. (2007). Cognitive style predicts entry into physical sciences and humanities: Questionnaire and performance test of empathy and systemizing. Learning and In- dividual Differences, 17, 260-268. doi:10.1016/j.lindif.2007.02.004 Blaikie, F., Schönau, D., & Steers, J. (2003). Student’s gendered experi- ences of high school portfolio art assessment in Canada, the Nether- Copyright © 2012 SciR es . 1210  A. SAVOIE, S. ST-PIERRE Copyright © 2012 SciRe s . 1211 lands, and England. Studies in Art Education, 4, 335-349. Blakemore, S. J., & Frith, U. (2005). The learning brain: Lessons for education. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd. Braconnier, A. ( 2000). L e s e x e d e s é m o t io n s. Paris: Odile Jacob. Carroll, J. M., & Yung, C. K. (2006). Sex and discipline differences in empathising, syste mising and autistic symptomatology: Evidence fro m a student population. Journal of Autism and Development Disorders, 36, 949-957. doi:10.1007/s10803-006-0127-9 Chen, W. J., & Kantner, L. A. (1996). Gender differentiation and young children’s drawing s . Visual Art Research, 22, 44-51. Chodorow, N. J. (1999). The reproduction of mothering. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. Coates, J. (2003). Men talk: Stories in the making of masculinities. L on- don: Blackwell Publishing Ltd. Cross, T. L., Speirs Neumeister, K. L. & Cassady, J. C. (2007). Psychol- ogical types of academically gifted adolescents. Gifted Child Quar- terly, 51, 285-294. doi:10.1177/0016986207302723 Duncombe, J., & Marsden, D. (1993). Love and intimacy: The gender division of emotions and emotion work. A neglected aspect of so- ciological discussion of heterosexual relationships. Sociology, 27, 221-241. doi:10.1177/0038038593027002003 Duncum, P. (1997). Subjects and themes in children’s unsolicited draw- ings and gender socialization. In A. M. Kindler (Ed.), Child develop- ment in art (pp. 107-114). Reston, VA: National Art Education As- sociation. Dumais, S. A. (2002). Cultural capital, gender, and school success: The role of habitus. So c io lo g y of Education, 75, 44-68. doi:10.2307/3090253 Flannery, K. A., & Watson, M. W. (1995). Sex differences and gender- role differences in children’s drawings. Studies in Art Education, 36, 114-122. doi:10.2307/1320743 Feinburg, S. G. (1977). Co n ce p t ua l content and spatial characteristics in boys’ and girls’ drawing of fighting and helping. Studies in Art Edu- cation, 18, 63-72. doi:10.2307/1319480 Focquaert, F., Steven, M. S., Wolford, G. L., Colden, A., & Gazzaniga, M. S. (2007). Empathizing and systemizing cognitive traits in the sciences and humanities. Personality and Individual Differences, 43, 619-625. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2007.01.004 Garber, E., Sand ell, R., Stankie wicz, M. A., Risner, D. , Collins, G., Zim- merman, E., Congdon, K., Floyd, M., Jaksch, M., Speirs, P., Spring- gay, S., & Irwin, R. (2007). Gender equity in visual arts and dance education. In S. S. Klein (Ed.), Handbook for achieving gender eq- uity through education (pp. 359-380). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erl- baum Associates. Golomb, C. (2004). The child’s creation of a pictorial world. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates. Guionnet, C., & Neveu, E. (2009). Féminins/masculins: Sociologie du genre. Paris: Armand Colin . Helmreich, R. L., Spence, J. T., & Holahan, C. K. (1979). Psychologi- cal androgyny and sex rol e flexibility: A tes t of two hypotheses. Jour- nal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39, 1631-1644. Hittner, J. B., & Daniels, J. R. (2002). Gender-role orientation, creative accomplishments and cognitive styles. Journal of Creative Behavior, 36, 63-75. doi:10.1002/j.2162-6057.2002.tb01056.x ISQ (2007). Statistiques principales de la culture et des communica- tions au Québec: Édition 2007. Québec: Gouvernement du Québec, Institut de la statistique du Québec. Keller, C. J., Lavish, L. A., & Brown, C. (2007). Creative styles and gen- der roles in undergraduates students. Creativity Research Journal, 19, 273-280. doi:10.1080/10400410701397396 Kellogg, R. (1969). Analyzing children’s art. Palo Alto, CA: National Press Books. Myers, I. B. (1962). The Myers-Briggs type indicator manual. Prince- ton, NJ: Education al Testing Service. Manson, C., & Winterbottom, M. (2012). Examining the association between empathising, systemising, degree subject and gender. Edu- cational Studies, 38, 73-78. doi:10.1080/03055698.2011.567032 McNiff, K. (1982). Sex differences in children’s art. Journal of Educa- tion, 164, 271-289. MEQ (2001). Programme de formation de l’école québécoise: Éduca- tion préscolaire, enseignement primaire. Québec: Le Ministère. Monteil, J.-M. (2008). Comportements et contextes scolaires. In A. Van Zanten (Ed.), Dictionn a i r e de l’éducation ( pp. 81-85). Paris: PUF. Nettle, D. (2007). Empathizing and systemizing: What are they, and what do they contribute to our understanding of psychological sex differences? British Journal of Psychology, 98, 237-255. doi:10.1348/000712606X117612 Norlander, T., & Erixon, A. (2000). Psychological androgyny and crea- tivity: Dynamics of gender role and personality t rait. Social Behavior and Personality, 28, 423-436. doi:10.2224/sbp.2000.28.5.423 Octobre, S. (2004). Les loisirs culturels des 6-14 ans. Paris: La docu- mentation française. Perraudeau, M. (1997). Les cycles de la différenciation pédagogique. Paris: Arma nd C oli n. Perrenoud, P. (1995). La pédagogie à l’école des différences. Paris: ESF. Przesmycki, H. (2004). La pédagogie différenciée. Paris: Hachette. Rogers, P. L. (1995). Girls like colors, boys like action? Imagery pref- erence and gender. Montessori Life, 7, 37-40. Salkind, L., & Salkind, N. J. (1997). Gender and age differences in pre- ference for works of art. Studies in Art Education, 39, 246-256. doi:10.2307/1320524 Savoie, A. (2008). Considérations sur les difficultés des garçons en arts plastiques: Approches différenciées et traits cognitifs liés aux genres. In F. Gagnon-Bourget, & P. Gosselin (Eds.), Actes du colloque sur la recherche en enseignement des arts visuels 2006 (pp. 93-100). Mon- tréal: CRÉA Éditions. Savoie, A. (2009). Boys’ lack of interest in fine arts in a coeducational setting: A review of sex-related cognitive traits studies. International Journal of Art and Design Education, 28, 25-36. doi:10.1111/j.1476-8070.2009.01590.x Savoie, A., Grenon, V., & St-Pierre, S. (2010). Comparaison de percep- tions autorévélées au regard des arts plastiques recueillies auprès d’élèves masculins et féminins d’une école secondaire. In A.-M. Émond, F. Gagnon-Bourget, A. Savoie, & P. Gosselin (Eds.), Actes du colloque sur la recherche en enseignement des arts visuels 2008 (pp. 93-101). Montréal: CRÉA Éditions. Speck, C. (1995). Gender difference in children’s drawings. Australian Art Education, 18, 44-54. Stoltzfus, G., Nibbelink, B. L., Vredenburg, D., & Thyrum, E. (2011). Gender, gender role, and creativity. Social Behavior and Personality, 39, 425-432. doi:10.2224/sbp.2011.39.3.425 Thorne, B. (1993). Gender play: Girls and boys in school. New Bruns- wick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. Tuman, D. (1999). Gender style as form and content: An examination of gender stereotypes in the subject preference of children’s drawing. Studies in Art Education , 41, 40-60. doi:10.2307/1320249 Tuman, D. (2000). Defining differences: An historical overview of the research regarding the difference between the drawings of boys and girls. The Journal of Gender Issues in Art Education, 1, 17-30. Wilson, M., & Wilson, B. (1982). Teaching children to draw: A guide for parents and teac h e r s. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. |