Secondary Prevention Following Coronary Artery Bypass Surgery: A Pilot Study for Improved Patient Education ()

1. Introduction

Advances in surgical techniques have resulted in excellent postoperative outcomes from coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) operations, despite the high acuity of patients in the current era [1,2]. Since coronary artery disease (CAD) is a chronic, progressive illness, optimal postoperative treatment of these patients should include preventive measures that have been demonstrated to limit future cardiovascular events, subsequent need for interventions, and improve outcomes [3-5]. Since an optimal prevention regimen is critical to achieving long-term success, systems of care should adopt integrative and multidisciplinary methodologies to assure that patients receive an ongoing benefit from CABG operations, with early initiation after the surgical procedure [6].

Previous studies have documented that patient compliance with secondary prevention regimens after CABG has often been inadequate, especially in relation to the four major drug classes that have been shown to be particularly efficacious (platelet inhibitors, beta blockers, lipid-lowering agents, and angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) or angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) [7-13]. Recently, a large multicenter trial, utilizing patients included in the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) database, showed that local “low-intensity” continuous quality improvement protocols designed to reinforce preventive strategies were very effective at assuring that postoperative patients were discharged from the hospital on an appropriate drug regimen [14]. It remains unclear if efforts focused solely on the time of hospital discharge are sufficient to affect longer-term compliance with these important measures [15]. The objective of this randomized, controlled study was to assess the influence of a multidisciplinary follow-up educational program on disease understanding, motivation to reduce cardiovascular risk, and secondary prevention medication prescribing following CABG.

2. Methods

2.1. Patient Population

Between January 2008 and January 2009, patients who underwent CABG at our institution were offered inclusion in this secondary prevention study. Patients who accepted entrance into the study and completed the entire program comprise the subject of this analysis. The study was approved by our Institutional Review Board and each patient gave informed consent.

2.2. Study Design

As standard care, all patients received instruction by teams of specialists during the postoperative recovery phase prior to hospital discharge. This included the inpatient cardiac rehabilitation team that stressed the importance of prevention, specifically physical activity. Additionally, each patient was counseled by a dietician and every patient who reported a tobacco use history was provided smoking cessation counseling. The cardiac surgical team, specifically physician assistants, was charged with prescribing indicated preventive medications (antiplatelet agents, statins, beta blockers, and ACEI/ARBs) prior to hospital discharge if the patient was eligible for the medication.

During the postoperative period, we randomized subjects to an intervention or control (“usual care”) group using a computer generated randomization scheme and sealed envelopes. Hypothesizing that hospital discharge might not be the optimal time to deliver an educational message to anxious postoperative patients and their families; we examined the effects of an additional educational intervention 4 - 6 weeks following the hospitalization. This intervention, conducted by a multidisciplinary team consisting of a pharmacist, dietician, and cardiac rehabilitation nurse, was designed to be an educational “booster” to reinforce the importance of secondary prevention, answer patient questions or concerns, and thereby increase understanding of evidence-based methods of prevention.

The “booster” consisted of a 3 hour intervention that included a general information group session accompanied by individually-tailored 30 minute meetings with 3 individual clinicians: each discipline was represented by 1 or 2 trained individuals throughout the study time period and discussions were initially scripted to attain the most consistency possible. None of the professional participants in the “booster” were involved in the patient selection, follow-up, data analysis, or overall conduct of the study. A plan of care was formulated and given in writing to the patient, his/her cardiologist and their primary care physician. No medication changes were ordered during the “booster”, but rather modifications were suggested to the referring physicians so that appropriate follow up and monitoring could be completed. Family participation was strongly encouraged during the “booster” sessions in order to enhance the quality of the interaction between the patient and the individual specialists. Data were collected by study coordinators at 3 distinct time points: hospital discharge (DC), and then at the 3 and 12 month intervals following hospital discharge. Demographics, clinical parameters, and medication-use data were obtained from the hospital’s electronic medical record and outpatient clinic records.

2.3. Study Outcomes

The electronic medical record was used to determine medication use rates at the three study time points and was compared between the groups. Medication use is reported as percent use among those eligible to receive the therapy. Eligibility was determined by the variables provided in Box 1. For medication use data, note that patients might have relative contraindications at the baseline time point (hospital discharge), that no longer existed at the 3 and 12 month time periods (for example, hypotension). Thus, more patients were considered eligible at the 3 and 12 month time points.

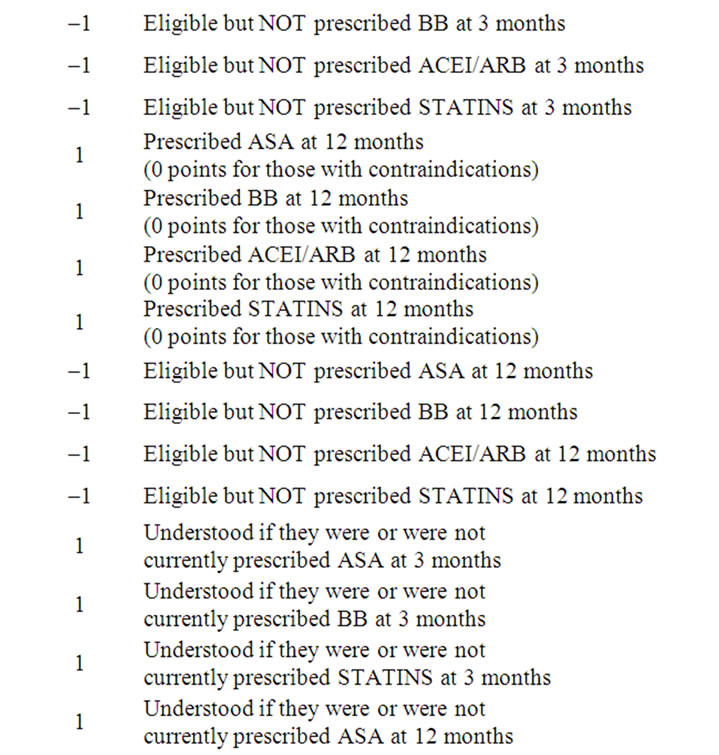

In order to comprehensively assess the efficacy of the “booster” intervention, we devised a Composite Heart Health Index (CHHI), which took into account improvement in risk factor parameters, indicated medication use, the patient’s awareness regarding their disease and prescribed medications. The variables used to calculate the score are presented in Table 1. Points were awarded when improvement was shown in risk factors (such as smoking status, body mass index, lipid levels, and blood pressure) between the time intervals. Points were also awarded when patients could correctly identify if they were or were not taking specific medications for secondary prevention. Points were deducted however when these medications were not prescribed to eligible patients. Scores from a 15 question “understanding” survey and a 6 question “motivation” survey were assessed.

The written surveys were administered during each of the three study time points. We divided the number of survey questions answered correctly by the number of survey questions answered and multiplied this value by

Box 1. Indications and contraindications to secondary prevention medications after coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG).

100 to obtain a survey score for both the understanding and motivation surveys.

2.4. Statistical Methods

The mean composite score and survey scores at the three

Table 1. Calculation of the Composite Heart Health Index (possible range –8 to 26 points).

time points were compared between the groups using a Wilcoxon Rank Sum test. Differences between medication use at specific time points, and other categorical data were compared with Chi square or Fisher’s exact tests. To compare the statistically dependent understanding and motivation survey scores at the different time points we used generalized estimating equations (GEE), to account for the correlated responses from the same subjects. Linear contrasts of the parameter estimates were performed to do pairwise comparisons between the three time points using Wald chi square tests. Alpha was set a priori at 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Population

During the study period 118 subjects (ages 42 to 86 year old) were screened, offered admission, and eventually consented to participate in this research project. These patients were randomized into the “usual care” and intervention (“booster”) groups. Patients who were unable or unwilling to complete the 3 surveys were dropped from the study. Of the original group of 118, 98 (49 in each group) ultimately completed the baseline, 3 month, and 12 month surveys, and thus were included in the final data analyses. Table 2 summarizes the study population’s demographics.

3.2. Composite Heart Health Index

In order to assess the effectiveness of our intervention, we evaluated the mean Composite Heart Health Index (CHHI) score between groups. The CHHI was not different at the 12 month time point between the groups (intervention 12.8 ± 4.5 points vs control 12.7 ± 4.9 points, p = 0.9405).

3.3. Medication Utilization

Figure 1 illustrates the changes in usage by eligible candidates for the four classes of prevention medications for the entire cohort. The prescription rate at discharge is high in all four groups ranging from 87% for ACEIs/ ARBs to 100% for antiplatelet agents. However there are significant declines in medication utilization rates for 3 of the 4 classes with time, first at 3 months and further at 12 months. There was not a significant difference between the control and intervention subjects, as shown in Figure 2.

3.4. Knowledge and Motivation Survey

Figure 3 suggests that there is a high rate of basic understanding about CAD, which is present at the time of discharge (after the standard patient education given to all patients), and improves significantly over time. Significant increases in “motivation” to reduce cardiovascular risk from baseline (hospital discharge) to the 3 and 12 month time periods were noted (see Figure 4). However, there were not significant differences between the control and intervention groups with respect to the survey results.