Interrogating the Intersection between Statutory Rent Control and Freedom to Contract in Nigeria ()

1. Introduction

Ownership is recognized, in law, as the highest right a person can possess over a property, whether realty, personality or chose-in-action (Clarke, 2006; Amokaye, 2004: p. 474; Omotola, 2006: p. 17) . Since no interest ranks higher than ownership, ownership clothes its possessor with absolutism (Abraham v. Olorunfunmi, 1991: pp. 74-75) with regard to the use to which the property is to be put to or not; the benefit derivable from and the collateral rights to be created over, on and/or in the subject property.

The concept of ownership evolved as a necessary corollary to the development of human society and the understanding of property as a thing to be possessed, either jointly or severally. As Bentham (Dias, 1970: pp. 367-368) puts it: “Ownership is needed to give effect to the idea of “mine” and “not mine” or “thine”. This idea becomes necessary only when there is some community of persons. Thus, a man by himself on a desert island has no need of it. It is when at least one other person joins him that it becomes necessary to distinguish between things that are his and those that are not his, and also to determine what he may do with his things so as not to interfere with his companion. Without society there is no need for law or for ownership.”

This postulation laid the foundations for the development of the labour theory of property (Kramer, 1997) and other theories, which discriminate between private and public properties. Therefore, in the realm of property law, there are two broad categories of property: private and public. Whilst private property is that which is vested in non-governmental hands, public property, in contradistinction, is that which is vested in the State and ensures for the benefit and use of the public. The fragile distinction between these classes of properties and the attendant legal incidences of both makes the foray of one into the other inexorable.

The fixed nature of land and the exponential growth of population have been credited with necessitating not only strict regulations on the distribution and usage of land but the elevation of state control over private property (Oni et al., 2007) . The police powers (Claeys, 2003: p. 1635; Amokaye, 2004: p. 483) of state over private property come in variegated forms: planning regulations and restrictions, zoning, conservationism and rent control. In this paper, our focus shall revolve around the practice of rent control (whether directly, by way of positive legislation, or indirectly, by way of negative legislation i.e. contractual rent review limitations) and how that intervention negates the rights to own property and the limitations imposed on the freedom to enjoy same as the owner deems fit.

The discussion here, shall proceed from an exposition of the origins and philosophical basis for the recognition accorded to private property, and by extension, the need to respect contractual relationships arising therefrom. An appraisal of the justification or otherwise of the incursion of state, by way of rent control simpliciter or qua rent review restrictions, into a purely contractual and private sphere of property law will be undertaken. The vertical and horizontal curtailment of contractual rent review clauses in leases by legislation will be discussed. In summation, attempts shall be made to stand against such state intervention and demonstrate that, the police power of the State, not only negates the principle of contractual freedom but constitutes a caustic aberration into an individual’s constitutional right to own and use property. A proper proposal for a rethink of the traditional approach to rent control measures whilst proffering equitable models of regulating rent without excessively bruising private rights and/or upsetting the rights-obligations balance in society, will be made.

2. Brief History of Rent Control

It is perceived that, while housing shortages is not a new phenomenon in human existence, rent control by state is not as old. John W Willis (1950: p. 59-60) has doubted the unverified assertion that rent controls were known in ancient Rome. Regardless, records show that in Europe, there were interventions by the state in the relationship between the landlord and the tenants; largely by way of decrees. Several efforts were, within this context, made by the state to ensure that greedy landlords did not take undue advantage of the scarcity of accommodation in Europe between the sixteenth and the eighteenth centuries. These controls were essentially in the forms of temporary moratorium on rent payments, reduction of rents payable based on the principles of equity, extension of time or delays for the payment of rents and evictions, etc. (Willis, 1950: pp. 61-67) One of the early recorded formal legislations on rent control is the Australian Fair Rents Act, 1915.

After this direct legislative experiment on rent control, a number of legislations were enacted for the same purpose across the continents. It, somehow, became the populist agitation for the state to apply its legislative authority to control rent. As a result of the world wars, housing scarcity became one of the major results of the economic difficulties imposed by the wars. This situation elevated housing shortages to social problems across the world. This was also made more prevalent by the growing population in South Africa, India, Continental Europe, etc. According to John Wills, the efforts to control rent in the United States was not by legislative approach. He posited that, apart from very few instances where some states attempted a legislative control of rent, rent control in the United States was based on public opinion and voluntary (Willis, 1950: pp. 69-70) . This approach, according to him, was severally criticized (National Defence Advisory Commission, 1941) as lacking in plans and clear principles.

As correctly observed by John Wills, the lessons that rent control teaches is that once such controls are imposed, they become very difficult to remove. It has also been shown that, the longer the control is in place, the more difficult it becomes to abolish (National Defence Advisory Commission, 1941: p. 71) . Regardless, improvements in the economy and the social conditions of the people naturally generates the oxygen to relax rent restrictions. This explains why John Wills argued that countries which experienced serious inflation found it more difficult to return to rent normalcy (Wright, 1940: p. 27) .

The history of rent control in Nigeria can be traced to the racketeering and over-crowding in Lagos as a direct result of the economic effects of the 2nd World War. Consequently, the English Emergency Powers (Defence) Act, 1939 was made to restrict the increase in the rent of residential premises in Lagos. Through the Regulations made under this Act, the operations of the law were extended into parts of the Northern, Western and Eastern Regions. Due to the increase in the scarcity of housing in the urban cities and the need to protect tenants against the vagaries of these shortages, the Increase of Rent (Restrictions) Act 1946 was enacted. The extent of which these regulations and legislative interventions succeeded in addressing scarcity of housing in urban centres in Nigeria remained unrecorded.

Legislative records show that the first formal legislation on rent control in Nigeria after independence is Rent Control (Amendment) Act, 1965. This was followed by the Rent Control Edict of Lagos State. Upon the creation of the States in 1967, and thereafter, the states began the race to manage their respective new urban housing challenges by the promulgation of various rent control legislations. Most of these legislations contain similar provisions. The fact that these states were created under the various military regimes with inherent unitary constitutions, seems to have induced this legislative trends (Obilade, 1979: p. 41) . This author argues that legislations have no prominence in the resolution of social problems.

3. Philosophical Basis for Private Property

In ancient Roman law, it was recognised that natural objects were divided into two broad categories: things which are susceptible to human control and things which are not. The latter category was further sub-divided into res communes, res publicae and res sanctae (Pound, 1922) . The former category was therefore left to the will of individual members of society. It is this individual will that led to the formation and establishment of the economic structure present in most societies. Pound makes this point succinctly when he wrote:

“Legal recognition of these individual claims, legal delimitation and securing of individual interests of substance is at the foundation of our economic organisation of society. In civilised society men must be able to assume that they may control, for purposes beneficial to themselves, what they have discovered and appropriates to their own use, what they have created by their own labor and what they have acquired under the existing social and economic order…It has been said that the individual in civilised society claims to control and to apply to his purposes what he discovers and reduces to his power, what he creates by his labor, physical or mental, and what he acquires under the prevailing social, economic or legal system by exchange, purchase, gift or succession.” (Pound, 1922)

It is in line with the above delineations and understanding of property that private property took on a life of its own. The evolution of more sophisticated societies, the growth of human population and the scarcity of resources stoked up the need to develop a coherent system of laws to protect and define the limits of and the interplay between state and individual rights over property (Waldron, 1985) .

Several theories have been developed, over the centuries, in justification of a bifurcation between public and private properties. It must be pointed out that, of the three media of the environment, land has always been viewed as falling into the private property domain. In fact, some theorists hold the opinion that, ownership of land is a “natural” right of man and forms an extension of the human person (Arnold, 2007: pp. 17-18) . Others have argued that, for a person to lay claim to land, he must have improved on it or taken active steps to appropriate it to himself with the desire to exclude all other persons therefrom (Pound, 1922) . The universality of the understanding that man has an inherent and natural right to property led to the codification of this right in Article 17 of the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights (United Nations Declaration of Human Rights, 1948) as well as in Article 14 of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Right (African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, 2004; Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, 1999) . A calm reading of the text of these declarations will not only reveal that they proceed from the premise that property is, first and foremost, subject to private ownership, but betrays a deliberate bias for the protection of private property against infringement by the state. While the right conferred on the individual to own property was positively expressed in the aforesaid declarations, the right to derogate from that right was negatively imputed. In essence, the intention to safeguard the proprietary rights of individuals from arbitrary invasion was clearly expressed.

The acceptance of man’s natural right to own property, was accompanied with a corollary; the power to deal with the subject property as the owner wishes. “The owner of a property can use it for any purpose: material, immaterial, substantial, non-substantial, valuable, invaluable, beneficial or even for a purpose which is detrimental to his personal or proprietary interest” (Abraham v. Olorunfunmi, 1991) . Therefore, what is inherent in ownership right is the power of alienation or disposition, whether absolutely or conditionally. The vehicle for such disposition, most often, is contract, in its pure sense or in equity. The paths of property law and contract have always been interlaced, prompting Pound to say that:

“Property and contract, security of acquisitions and security of transactions are the domain in which law is most effective and is chiefly invoked. Hence property and contract are the two subjects about which philosophy of law has had the most to say.” (Pound, 1922)

What, therefore, is contract?

4. Philosophical Basis for Contract: Is There a Right to Contract?

A contract is an agreement which the law will enforce or recognize as affecting the legal rights and duties of the parties (Sagay, 2001: p. 1) . According to Niki Tobi, a contract is an agreement between two or more parties which creates reciprocal legal obligations to do or not to do particular things (Orient Bank Nig Plc v Bilante International Ltd., 1997) . The necessity of contracts in everyday life cannot be overemphasized: “Trade and commerce would be chaotic, if not impossible, if the law permitted a promisor to break his promise without at least placing him under an obligation to pay compensation for the loss occasioned by his default.” (Sagay, 2001: p. 1) Just like the right to own property, the right to contract is private. This right evolved partly as an extension of the right to personal liberty (Blum, 2007: p. 8) and as a resistance to state interference into individual freedoms. Atiyah (1981: p. 1058) states that:

“At least it may be said that the idea of freedom of contract embraced two closely connected, but none the less distinct, concepts. In the first place it indicated that contracts were based on mutual agreement, while in the second place it emphasized that the creation of a contract was the result of a free choice unhampered by external control such as government or legislative interference.”

Liberty, in this context, as is used above, encompasses not only the right to physical movement without restraint, but the natural right to freedom of thought and expression of self-will (Garner, 2014: p. 779) . In exercise of this liberty, individuals freely enter into binding contracts among themselves and the courts, which are mechanisms of state, enforce them as a matter of state policy (Sapphire v. National Iranian Oil Company, 1963, p. 181) . In fact, it has been held that, the duty of courts is not to make contracts for persons but the interpretation and enforcement of same (Alade v. ALIC Nig Ltd & Anor, 2010: p. 59) . However, as is the case with private property, the right to contract is not unfettered. The principles of “illegality” and contrariness to “public policy” have been used as agents to keep the right to contract in check. As Ogwuche (2008: p. 341) puts it: “As a general rule the courts will neither enforce a contract which is illegal or which is otherwise contrary to public policy, nor permit the recovery of benefits conferred under such a contract.” It is, therefore, safe to conclude that, whilst the creation of contracts is exclusively within the control of the individual, the mode and means of enforcement of the said contracts are largely without.

Having shown that property and contract have their roots in private ownership and personal liberty respectively, the stage is now set to undertake a discourse of the propriety or otherwise of state interference, by way of rent review control, with these private rights.

5. What Is Rent Control?

An understanding of rent control would necessarily proceed from a definition of rent itself (as well as other relevant concepts such as Lease and Tenancy). Rent is a payment which a tenant is “bound by contract to make to his landlord for the use of the property let”. Rent also “includes any consideration or part of any crop rendered, or any equivalent given in kind or in labour, in consideration of which a landlord has permitted any person to use and occupy any land, house, premises, or other corporeal hereditament” (Rent Control and Recovery of Residential Premises Law, 1997) . The most recent statutory definition of rent is as contained in the Lagos State Tenancy Law (2011) which provides that:

“Rents includes any consideration or money paid or agreed to be paid or value or a right given or agreed to be given or part of any crop rendered or any equivalent given in kind or in labour, in consideration of which a landlord has permitted any person to use and occupy any land, premises, or other corporeal hereditament, and the use of common areas but does not include any charge for services or facilities provided in addition for the occupation of the premises.”

The legal incidences of rent, from the above definitions, are that rent is:

1) paid with cash, other consideration(s), labour (i.e. in kind) or by conferment of a value or right acceptable to the landlord (G. B. Ollivant Ltd. v. Alakija, 1950) ;

2) there is no condition that rent must be paid before or concomitantly with the commencement of the tenancy. It may be present or futuristic (i.e. to be paid at a later date mutually agreed by the landlord and the tenant);

3) paid for the use and occupation of land, built premises, corporeal hereditament or common areas; and

4) rent is not chargeable for services or on fixtures.

Apart from the financial benefit derived by the landlord from rent, payment of rent also plays a non-pecuniary role; it is an “acknowledgement made by the tenant to the lord of his tenure” (Chianu, 2006: p. 239) . Rent, therefore, defines the legal relationship of the parties to a property. It should also be understood, as stated in a case and by Professor Smith, that payment of rent is not one of the pre–requisite for a valid tenancy or lease (Smith, 2013: p. 301) .

Having explained the underlying ingredients of rent, it is important to state that, since payment of rent implies a tenurial arrangement between the grantor and the grantee, such arrangement can only confer possessory and usufructuary rights on the grantee. As rents are paid only for the use and occupation of land or other premises, they are generally payable under tenancies and leases. A tenancy or lease (Chukwu, 2008: p. 63) “arises when the owner of an estate in land grants, by means of a contract between the parties, the right to the exclusive possession of his land or part of it to another person, to hold under the grantor for a term of years.” (Smith, 2013: p. 246; Jack-Osimiri, 2016) For there to be a valid lease or tenancy, the following must be present: parties, the property to be demised, length of the term, rent to be paid and date of commencement (U.B.A. Ltd v. Tejumola & Sons, 1988) .

From the above definitions of a lease or tenancy it is apparent that, they are created out of and in exercise of the inherent contractual freedom of parties. If the above statement is taken as true, then it must be accepted that the terms of the lease agreement, including but not limited to the rent payable, are subject to the whims of the parties. As put by Banire (2003: p. 62) : “To elaborate further, during the early days of the evolution of a lease, the relationship was founded on purely contractual basis.” This position has received judicial imprimatur in a host of cases, notable of which is Udih v. Izedonmwen (1990) , where the Court, per Ogundare, J.C.A (as he then was), held that:

“Rent is a matter of agreement between the parties which agreement may be express or implied. The relationship of landlord and tenant existing between [the deceased landlord] and the appellant was a contractual one which the [landlord’s successor-in-title] succeeded to…It follows therefore that Exhibit G being a unilateral action of the respondent is ineffective to raise the rent from N50 to N500 per month.”

Therefore, state interventions in rent bargaining, by way of statutory rent control, detracts from the foundational presuppositions of contractual freedom upon which landlord and tenant relationship is based. Before we explore the pros and cons of rent review and its control, it is imperative to define rent control (Basu & Emerson, 2003: p. 223) . “Rent control is standard ceiling placed on the rent that a landlord can charge” (Oni, 2007: p. 2) . Again, rent control “is a law placing a maximum price, or a ‘rent ceiling,’ on what landlords may charge tenants” (Block, 2018) . The preamble to the Rent Control and Recovery of Residential Premises Law (Laws of Lagos State Nigeria, 1997) reads as follows: “A Law to Control the Rent of Residential Premises, to establish the Rent Tribunals and for other purposes connected therewith”. The law went further to classify Lagos State into various zones, prescribe a cap on the rents payable for properties in each zone and limits the length of time for which rent can be demanded or payable in advance. This law, and indeed all other rent control laws, in essence, are anti-contract; they shackle the contractual freedom of the individual and establish a dirigisme rent system. At Section 3(1) (2) (3), the law provides that:

“(1) As from the commencement of this Law it shall be unlawful for the landlord to accept any rent in respect of any accommodation to which this Law applies which is in excess of the standard rent prescribed for the type of accommodation provided that the landlord may apply to the tribunal, to vary the standard rent.

(2) Where any rent is higher than the standard rent prescribed for the type of accommodation under this Law, the tenant shall pay as from the commencement of this Law, the standard rent.

(3) Where any rent is less that the standard rent prescribed for the type of accommodation under this Law the tenant shall continue to pay, as from the commencement of this Law, the rent until the Tribunal makes as order varying the rent.”

Again, by Section 4 (Lagos State Tenancy Law, 2011) , penal sanctions were prescribed for any contravention of the provisions of the law. This provision, clearly, seeks to quasi-criminalise the breach of rent control and its review provisions under the Law.

Closely related to rent control is rent review. Although both concepts appear synonymous, they vary in their origins and application. Whilst rent review has its roots in contract, rent control, as have been shown above, is a creation of statute and usually induced by public policy. But, the point needs to be made that, rent review is a species of rent control (by way of contract). What then is rent review? Rent review is the right reserved by a lessor or landlord to vary the reserved rent in a lease (British Gas v. Universities Superannuation, 1986) . The justification for the inclusion of rent review clauses in leases is to ensure that rents payable for demised properties keep pace with “current market value from time to time of the demised premises” (Imhanobe, 2002: p. 232) and to assist the landlord to maintain the property, especially having regard to depreciations on same. Rent review may be limited in time (i.e. vertical) or quantum (i.e. horizontal). Therefore, rent review clauses in leases and other property-use agreements essentially seek to provide a contractual as well as determinate basis for the periodic reconsideration and renegotiation of rents payable by the lessee to the lessor (Cobra Ltd v. Omole Estate & Investment Ltd., 2000) . The misconception which has largely influenced statutory intervention in this regard is that, rent review clauses present an avenue for the incessant increase of rents by landlords. Although empirical evidence seems to support this misconception, the legal basis for the insertion of rent review clauses in leases is to provide an outlet for both parties to the lease to negotiate future rents within the context of economic, social and environmental realities in the society. That being the case, it is beyond dispute that, rent review falls within the exclusive private rights of the parties. Rent review clauses appear to have crept into public sector housing schemes.

6. Justification for Control of Rents and Rent Review

Rent control has its roots in the utilitarian role of the state in the lives of its citizen. Under the Nigerian Constitution, the objectives of the government include to ensure that “the economic system is not operated in such a manner as to permit the concentration of wealth or the means of production and exchange in the hands of few individuals or of a group” and the provisions of “suitable and adequate shelter” for its citizens. In support of this role of government, certain theories have been developed. The most prominent of these theories is that canvassed by Lord Brown-Wilkinson (Hammersmith and Fulham LBC v. Monk, 1992) . The jurist argued that, although leases are created by contracts, the interest created upon the consummation of the lease agreement is transmuted from a mere contractual interest to a proprietary interest. He argued further that:

“The lease provides a classic reminder of the fact that a contract between two persons can, by itself, give rise to a property interest in one of them… The contract of tenancy confers upon the tenant a legal estate in the land; such legal estate give rise to rights and duties incapable of being founded in contract alone.”

This interpretation of leases draws support from the legal incidences of a lease, especially as leases confer on the lessee legal interests and rights wider in scope than those derivable under contractual relationships. In this light, leases are seen as creating interests (i.e. estates) in land which come under the regulation of the state (Wikie & Cole, 1993: p. 3) . Therefore, the argument of the state will go like this: if leases create estates in land and estates are the basis of property ownership or holding under the law, then the state has the inherent power to legislate on how estates within its territory are to be used (Land Use Act, 2004) . In this light, the state finds an explorable niche to implement its objectives of achieving affordable housing, wealth re-distribution and some measure of social equilibrium (Singer, 2006: p. 311) in the face of rising population. Notwithstanding the ingenuity of this argument, the fact that it proceeds from and acknowledges contract as the root of the estate created by leases whittles down its viability. As Banire (2003: p. 65) points out: “But for the simple fact that it [leases] cannot still divorce itself from the contract antecedent, it could not fit in strictly into the absolute class of estate per se.”

Other arguments in support of rent control are the “social obligations of land-ownership” (McAuslan, 1974: p. 135) and “social cohesion” (Sax, 1983: p. 490) theories. These theories argue that, just as every right has accompanying obligations, the right to own property carries with it the concomitant social obligation to put it to fair usage and to ensure social cohesion. As Blackstone (1979: p. 1058) puts it:

“This natural liberty…being a right inherent in us by birth…But every man, when he enters into society, gives up a part of his natural liberty, as the price of so valuable a purchase; and, in consideration of receiving the advantages of mutual commerce, obliges himself to conform to those laws, which the community has thought proper to establish.”

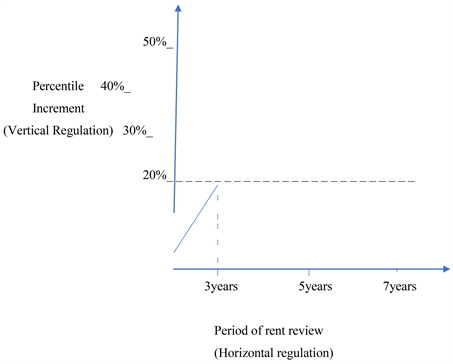

It is in the light of the above, that States regulate and limit the rights of parties to effect rent reviews. Section 2(1) (2) (3) (4) (Rent Control and Recovery of Residential Premises Law of Lagos State Nigeria, 1997) is a classic example of a vertical and horizontal regulated rent review legislation. It provides as follows:

“2. Standard Rent

(1) As from the commencement of this Law, the standard rent prescribed by the Governor for the purpose of this Law shall be payable in respect of the type of accommodation to which it applies.

(2) The standard rent referred to in subsection (1) of this section shall be subject to review every three (3) years or such other period as the Governor may by order prescribe.

(3) The increase on the standard rent at every period of review shall not exceed 20% of the standard prescribed in the order to this Law in respect of the type of accommodation to which it applies.

(4) The standard rent shall supersede any rent between the landlord and the tenant and any order made in respect of the standard rent shall bind all persons including the landlord, tenant or mortgagee of such premises.”

This law puts a cap on both periodic (horizontal) and percentile (vertical) rent reviews. The provisions of the law reproduced above can be graphically represented as follows:

Whilst rent control might not be suited for a free market society like Nigeria, unregulated rent review is. This is because, the underlying principles of rent review is compatible with those of a free market society; the person is centre of both concepts.

The parties to the leases agreement exercise their contractual freedoms when they negotiate, agree and reserve the rent to be paid on the lease. However, this freedom is taken away when the State intervenes by statutory rent controls (whether directly or indirectly). In most societies where the State has intervened, they justify such actions by invoking the “equal-unequal” argument. Therefore, rather than leave the tenant, who obviously cannot match the bargaining power of the landlord, helpless, the law should step in and provide a measure of protection for him.

Despite the lofty foundations on which the theories in support of rent control and its review are premised, the point still remains that, they are misplaced for a market or capitalist economy such as Nigeria.

7. The Challenges of Rent Control

However plausible the argument in support of rent control and its review in leases may appear, it suffers a number of drawbacks. Paramount among these is that it places a vicarious obligation on the shoulders of the property owner for the rights to be enjoyed by the lessee. The property owner is burdened with a regulated rent regime whilst the tenant is unencumbered. This unequal distribution of rights and obligations detracts from the market economy which has taken roots in Nigeria. It also ignores the possibility of landlords’ dependency on income from rents for subsistence in a deregulated economy like Nigeria.

Every free market is built on the principle of equality. Equality as used here is in two senses: equality of all men and equal right to use one’s acquisitions to pursue happiness. In the first sense, Sarkar (2011: pp. 35-36) argues that:

“The market is posited as the main domain of mediating social relationships and postulating the contractual agreements that bind these relationships as free, which are governed by the norms of fairness and equality. It is fair because equal is exchanged for equal and each sells (properties) which are at his or her disposal and without coercion. The foundation of fair exchange is equality. Consent is the bedrock concept of the contractual relationships which govern the market economy. The parties involved in these transactions are considered as private individuals, equal before the law, who enter into such transactions willingly or voluntarily without succumbing to any coercion. The “contractual obligation [is] seen to arise from the will of the individual” and [i]individuals [will] themselves into positions of obligation, i.e. there has been a “meeting of the minds”.

Therefore, since all men are equal in the eyes of the law and are free to contract as they deem fit, the State should honour their voluntary agreements without inhibition. In this light, lease agreements and any reserved rent therein should be viewed as an expression of equal self-will and therefore inviolable. In the second sense, equality connotes the equal distribution of rights and obligations among citizens. In other words, no citizen or class of citizens should bear more societal obligations than his fellow citizen. Therefore, in seeking solutions for societal problems, a class of persons should not be made to shoulder the obligations for rights to be enjoyed by another class. This argument draws inspiration from the principle of reciprocity of rights and obligations which advocates for the “equality in rights and obligations” (Wilson, 2007: pp. 228-229) among citizens. As Swift (1795: p. 6) puts it: “whether men possess the greatest, or the smallest talents, they have equal claims to protection, and security in their exertions, and acquisitions.”

Rent control, therefore, tips this scale of equality in favour of the lessee who enjoys the benefits of a regulated rent regime whilst the lessor is afforded no legal protection. This unequal distribution of rights and obligations works hardship on the property owner especially in the Nigerian economic milieu where year-on-year inflation (Central Bank of Nigeria, 2022) impacts on the cost of building construction. In such a situation, the right of the property owner, who has expended huge sums of money in erecting the building, is limited by laws which do not keep pace with present national and global inflationary trends. In fact, in some laws, the right of the property owner to increase rent is regulated not only in respect of intervals between one increment to another but a cap is placed on the percentile limit of increment permissible irrespective of the rate of inflation. Claeys stated:

“When Madison says that government ‘secures to every man, what is his own’, he emphasizes that government must do so ‘impartially’. When Kent speaks of property rights, he stresses that such rights are consistent with the reciprocal rights of others.” (Claeys, 2003)

Apart from the fact that rent control discriminates against the property owner, it places the property owner in a legal quagmire since such rent restrictions do not qualify as compulsory acquisition which entitles him to compensation. Section 44(1)(a) and (2)(c) provides as follows:

“44

(1) No moveable property or any interest in an immovable property shall be taken possession of compulsorily and no right over or interest in any such property shall be acquired compulsorily in any part of Nigeria except in the manner and for the purposes prescribed by a law that, among other things-

(A) Requires the prompt payment of compensation therefor;

(2) Nothing in subsection (1) of this section shall be construed as affecting any general law

(c) relating to leases, tenancies, mortgages, charges, bills of sale or any other rights or obligations arising out of contracts;”. (Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, 1999)

The above provisions, in effect, gave licences to state governments in Nigeria to legislate over rent control and coated the rent control laws already passed by them with constitutionality. Comparatively, the courts in the United States of America have used the Takings Clause in their Constitution to hold that any interference (whether by law, regulation or action) into the property owner’s right to disposition, use and control of his property amounts to a taking (Penn Central Transportation Co. v. City of New York, 1978) which attracts compensation.

Another consequence of rent control is that, it dampens the enthusiasm of property developers to build new housing units since the returns on their investment on the building is greatly diminished by state regulations (Sarkar, 2011: p. 36) . This is the argument of the “Investment Backed Expectation” theory (Lorreto v. Teleprompter Manhattan CATV Corp, 1982) . The effect rent control has on urban development, using this theory, was painted by Holcombe and Poweel (2009: p. 152) when they described the boom in development engendered by the repeal of rent control laws in the Boston and Cambridge municipalities of Massachusetts, U.S.A. He wrote thus:

“Rent decontrol has led to increases in housing investments at all levels of the market. A study by MIT housing economist Henry Pollakowski (2003) found that investment in Cambridge increased by 20 percent above and beyond what would have been expected if rent control had remained in place. And both high-income and lower-income neighborhoods benefited, supporting the typical economic argument that price controls on rental properties discourage investment and lead to decrease quality of rental housing.”

It has also been shown that rent controls lead to the reduction of rental supply. It also leads to the deterioration of the quality of rentals (Sims, 2007: pp. 129-151) . A study into the economic effects of the removal of rent control in Cambridge, Massachusetts has established that the removal of rent control led to a significant increase in housing stock over a period of ten (10) years (Autor et al., 2014: p. 661) . What appears conclusive from these studies, is that rent control is not only antithetical to the foundations of modern capitalism but induces loss of investment potentials in the areas of housing and its related assets (Diamond et al., 2019) .

8. New Approach to Rent Control

The Rent Control and Recovery of Residential Premises Law (1997) and most other rent control laws in Nigeria were promulgated during the military era in Nigeria. It is, therefore, not surprising to see draconian provisions which are atavistic of military dictatorship in such legislations. Most of the rent control legislations in Nigeria demonstrate a complete disregard for the sanctity of contractual freedoms and the doctrine of civil agreements. However, even if it is universally accepted that, the police power of state is an invaluable instrument for planning and social ordering (Hadacheck v. Sebastian, 1915) , same should not be used to violate private rights such as the right to contract, as exemplified by rent control laws. Therefore, since rent control unduly yokes the property owner with obligations the benefit (i.e. right) of which are accruable to another, the lessee/tenant, same upsets the right-obligation balance in society and creates legal inequality. In such a case, rent control veers off the path of “regulation” and teeters into the realm of “taking” which desecrates private rights. Claeys (2003: p. 1606) made this point when he remarked:

“Whenever a positive law restrains a right incident to property ownership, whether control, use, or disposition, that law risks impermissibly abridging the free exercise of property rights. The law is not per se invalid, but the restraint on property requires further justification. The law can be justified as a bona fide ‘regulation’ of property rights if it restricts the use rights of every person in order to enlarge both the personal rights and freedom of action of everyone regulated. By contrast, if some individuals lose more than their equal share of use rights without gain, the law is not a ‘regulation’ of right, but rather an ‘abridgement,’ ‘invasion,’ or ‘violation’ of right.”

This is the summation of the argument that I have put forward above.

The question which begs for an answer, therefore, is: How can government create an equitable and just system of determining rent without breaching this basic freedom? The answer to this question is two-pronged: restrictive rent control and a redistributive compensation system.

By restrictive rent control, I mean a system of rent control which applies restrictively to state-owned or state-developed residential schemes. In this sense, the state will be at liberty to impose rent controls over such state-owned or state-developed residential schemes since the land/property is not subject to private ownership rights. This was the reasoning in the case of People vs. Platt (1819) where the New York Supreme Court of Judicature held that the state could not limit the river property rights of the respondent (Platt) and his successors because what was granted to him when he acquired the property was a general right without restriction, therefore, he held an “exclusive” right over the river property since the grant was not subjected to any navigational servitude to the state. The reasoning of the court in Platt’s case can be applied in Nigeria where the Land Use Act (2004) declares that all lands in the territory of a state are “vested” in the Governor and what he grants to individuals is a right of occupancy. This being the case and bearing in mind that a holder of a right of occupancy has “exclusive rights” over the land against all persons except the Governor1, the holder of such right can resist any rent control law attempting to subject him to any rent control regime not provided for in the certificate of occupancy. This argument is buttressed by the fact that, the holder of a right of occupancy has the “sole right to and absolute possession of all improvements on the land”1.

The restrictive rent control model will alleviate the danger of infringing on private property right by either restricting rent control to state-owned or state-developed residential schemes or ensuring that rent control conditions are inserted into certificates of occupation when grants are being made.

On the other hand, the state may introduce a compensation system to balance the right-obligation equation between property owners and their lessees. This can be achieved by granting of tax waivers and/or holidays, Ground rent or Land Use Charge rebates to property owners who are affected by rent control laws. In this way, the property owner regains what he has lost due to rent control and the society (inclusive of the lessee) loses tax payers money/revenue, thereby balancing the right-obligation equation. In the state of Massachusetts, U.S.A, property owners are at liberty to voluntarily opt in or out of rent control regulations and those who opt in are compensated by tax waivers or reductions. Writing about this arrangement, Holcombe stated:

“In addition to making the compliance voluntary, cities are required to compensate landlords for the difference between market and controlled rent, with the stipulation that such compensation [come] from the municipality’s general funds, so that the cost of any rent control shall be borne by all tax payers of a municipality and not by the owners of regulated units only.” (Holcombe & Poweel, 2009: pp. 151-152)

The implementation of the above models will serve the trilateral purposes of preserving the sanctity of contractual relations, ensuring the protection of private property interests and maintaining the right-obligation equilibrium in society.

9. Conclusion

Arising from the proposition that the right to own a property ensures subject to a certain social obligations to put it to fair usage for social wellbeing, it has been argued that rent control may be adverse to free market societies like Nigeria. The inherent rights associated with the freedom to contract create a platform which enables the property owner to negotiate with their prospective lessees. The power of the State to control rent challenges this right in a host of ways and, as a result, creates an imbalance between the interest of the lessors and those of the lessees. This sense of, or actual, imbalance has negative productive consequences in the housing sector.

Since every free market draws its legitimacy from equality and fairness, it is critical that any policy or legislative intervention which seeks to either control rent or set up rent review mechanism must balance both contending interests so as not to discriminate against any. It is not the objective of any society to be discriminatory.

Considering the potential difficulties which this policy creates in the housing supply chain, it is viewed that legislative action will be necessary to properly address the imbalance and establish a system of rent control which will be sustainable. The introduction of certain waivers to housing suppliers in the species of property tax, tax holidays and allowances are suggested. Those who supply properties to which rent control and review discounted laws are applicable should be beneficiaries of a well set out tax holidays and a land use charge mechanism so as to mitigate the carrying cost for controlled rent. Additionally, the legislative should be subject to periodic reviews in the light of emerging developments.

NOTES

1Land Use Act, 1978.