Socio-Economic Development, Globalization and the Need for Heritage Policy in Qatar: Case Study ()

1. Introduction

The impact of economic growth and globalization affects heritage in every nation. UNESCO guidelines to protect cultural monuments and sites are attractive yet a balance between cultural heritage preservation and social and economic development in practice inheres difficulties.

Holistic approaches in maintaining such a balance consider activities such as the education, the general policies, the preservation, the ecosystem supporting artists, the cultural and creative professionals in the region, the gender equality, the international cultural relation, with the culture as a driver for sustainable development.

In any case, heritage policies surround the preservation of traditions, identity, and culture (James & Winter, 2017). The role of government with regards to conserving heritage is usually placed under specific departments, branches, or government agencies to uphold, implement and further develop heritage policies (Pendlebury, 2015). To maintain the value of heritage, governments play an important role with regards to leadership and establishing key polices, which in turn should be holistic, practical, sustainable, and integrated in terms of approach. What’s more, government should be working towards how heritage may be affected and lay foundations through polices to protect heritage (Janssen et al., 2014). A brief outline of Qatar’s assets is indispensable, as the main issue of this paper focusing on the economy, society, and an integrated cultural heritage policy amidst the modern activities.

Located in the Qatar Peninsula, in the North-Eastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula, the nation is part of the wider Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) population, having a long history with Saudi Arabia to the South and the island of Bahrain nearby (Fromherz, 2017). Evidence of human habitation within Qatar is found to date back more than 50,000 years ago, in the Stone Age. Furthermore, Mesopotamian artefacts have been found in western settlements, in an area called Al Da’asa, North of Doha. Also, in Al Khor, evidence of trade relations between Qatari inhabitants and the Kassites from modern-day Bahrain is also evident (Zahlan, 2016). Becoming a pearl trading centre in the 8th century, Qatar’s authority was occupied by many settlements and by 1871; the Ottomans expanded their territory to include Qatar.

Briefly, Qatar’s important cultural assets include tangible and intangible heritage going back from 19th c to Islamic and prehistoric eras (Smith, 1970; Magee 2014: pp. 50, 178; Muhesen and Al Naimi, 2014; Cuttler et al., 2011; Kapel, 1967; see, also, World Heritage, 2014). Over the centuries Qatar due to its geographical position is influenced by a multitude of different powers, such as the culture of Ubaid (5th millennium), the ancient periods of the Seleucid to Sasanian Empires (3rd century B.C.E. to 7th century C.E. at the time of the advent of Islam) (Althani, 2013) and the Abbasid Caliphate (750-1258 C.E.). The Gulf was a crucial commercial link between the East and the West during all these times. Overland trade routes went through the Arabian Peninsula’s western coast and provided links to Qatari villages and cities, including Murwab, Al-Huwailah, Al-Zubarah and Al-Bidda—the forerunner of Doha. Examples include rock art carvings e.g. Al Jassasiya, for protection, documentation and cultural tourism (El-Menshawy, 2017; Deacon, 2006), the Al Zubarah Archaeological Site, which flourished as a pearling and trading centre in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, and offers outstanding testimony to an urban trading and pearl-diving tradition, The Old Palace in Doha, the Khor Al-Adaid Nature Reserve, the Bir Zekreed and Ras Abrouq areas, Muruab (9th - 11th c.) and Al Zubarah archaeological sites, the Jazirat bin Chanam island, the Al Jumail traditional village, the Arrakiyat and Al Thaqab forts. Qatar’s geographical setting with its importance of the trade and commerce of this Gulf region, and its seasonal coastal installations that have been documented since Antiquity, and has put the country at the crossroads of both maritime and overland trade routes. Merchants made several stops along the coast to trade goods such as pearls and horses, sandalwood, silver, incense, jewellery, spices, clothing. The Mughals, Chinese, and Europeans, amongst many others, used it to adorn their jewellery, for gift giving, and for textile embroidery. In particular, as a result, the pressure of harvesting them grew, creating a sustainable economy based on the pearl trade.

On the other hand, immaterial cultural heritage, or “our cultural sensitivity”, comprises the intangible heritage, which include identities, languages and dialects, musical rhythms, arts, folk tales, biographies, epics, nomadic poems, oral tradition, skills and crafts, as well as, tastes, folk imaginations and collective memory (see Al-Hammadi et al., 2021).

Being under British protection from 1916 following World War 1, by the 1950s-1960s Qatar saw great oil revenues that brought prosperity, immigration, and social changes. Officially gaining total independence in 1971, Qatar terminated the British treaty relationship (Kamrava, 2015). Although young, Qatar has a rich history and seen many changes in a small amount of time, yet, currently has clear objectives and policies in place to guide its international polices related to sports, education, and natural resources. However, there is an absence of inventories of tangible and intangible cultural heritage in Qatar, there needs to develop one. Furthermore, the country must also develop policies for safeguarding its cultural heritage, something which in recent years has begun to seek ways to create clear policies to protect and preserve its cultural heritage.

A way to define a set of heritage restoration-preservation tools and an integrated sustainable conservation strategy as part of deliberate planning and design processes for Qatar, has been proposed which argues for a sustainable future scenarios for the survival of vernacular architecture and historic buildings in Qatar through their sustained adaptive (re)use (Fadli and Al Saeed, 2019). Qatar’s key sectors is trying to create their own policy strategies.

This article argues Qatar’s benefit by recentralising focus on to heritage policies. Issues of Qatar’s heritage policy regarding safeguarding of cultural Heritage is deemed important. The objective is to explain and propose an integrated model-approach to management, documentation, exposition, of material and immaterial culture, and discusses a key question: what are the main factors that are creating the need to cultivate models of intellectual property rights over tangible and intangible cultural heritage in Qatar? How social, economic, heritage aspects are intertwined and interlinked to the present and planned future Qatar’s policies? The need to protect Qatar’s cultural heritage has become a matter of great significance. For the country, heritage protection means a promotion of its national pride, strengthening and reflection of its national identity. It also means improving and enriching the country’s tourism, as well as connecting the country to global communities, and right enough the government allocates values, importance and responsibility sense to cultural heritage materials.

Our present work’s structure commences with the Qatar’s present key sectors for policy strategy, introduces the need to focus to the heritage sector and its importance and added value, discuss the advantage of economic growth to support cultural heritage, and explains the harmonization and alignment with the UNESCO policies, and finally proposes a model of balanced development between society, culture, education with sustainability.

2. How Has Qatar’s Key Sectors Trying to Create Their Own Policy Strategies?

Although there is no official heritage policy in the state, extensive efforts are made by different sectors to connect people with their land, culture, heritage and past. These efforts aim to connect historical Qatar with today Qatar. Hence, a construction of national heritage narratives with an emphasis of the original identity are enhanced by those sectors such as culture, sport, education and Natural Resources and Energy. Those sectors act as policy and strategic makers of cultural heritage preservation at a time of globalization and modernization, which is a crucial time for Qatar. The following discussion highlights briefly examples of efforts and attempts that are initiated by some sectors as policies to safeguard the local cultural heritage.

2.1. Sporting Sector

In the last decade, the world has witnessed a significant increase in Qatar’s scope for events, especially in terms of sports competitions. It is interesting that Qatar has placed a significant focus on sporting events and in this context, the motives behind this phenomenon merits further understanding. As Qatar has grown and developed its economy and put in place milestones in the form of national visions, substantial efforts are seen in promoting and hosting events that draws international attention on to this small Arab state. There are a several reasons for this sporting events strategy, as they are used as policy instruments to influence certain sectors within the country. For instances, there is a correlation between Qatar’s national objectives as a motive that supports its agenda with private businesses, sporting and tourism sectors, and perspectives with public officials (Weber, Ali-Knight, and Khodr, 2012). Another argument is that sporting events act as impetus for the countries globalization and modernisation goals, as well as being further integrated into the international community, economic diversification, and its own social development as it encourages physical health and interest in sports from within (Reiche, 2015). Lastly, it displays the countries competitive spirit within the region. Therefore, like other sectors, sport sector integrates cultural heritage within its international events. For example, in 2018 when Qatar entered the tournament of 2022 World Cup cultural heritage of the state was highlighted in that occasion. During that event a 2.45 minutes video filmed a Qatari young boy walking in the desert picking up the desert rose and simultaneously a large desert rose emerged from the sand behind the boy with the iconic Qatari animal the Oryx (Bounia, 2018). From within this short video international audiences saw symbols of the Qatari heritage and culture, the Oryx, the endless desert, the boy with his traditional outfit and the desert rose. At the heart of an international sport event, Qatari cultural heritage uniquely and proudly placed, which reflects the desire of the sport sector to showcase Qatar’s culture. Accordingly, it seems clear that sport leaders have made the use of symbols of Qatari culture and heritage an essential part to promote their various activities inside and outside Qatar as a policy for introducing local heritage.

2.2. Education Sector

Educational development has been known to play a significant role in terms of societal progress at many levels. Qatar, including many Arab countries have worked towards redeveloping and improving their educational systems. Literacy rates in Qatar is 94.71% (UNESCO, 2017), which is higher than North American countries and many Western European countries. This highlights Qatar’s push for improving learning as part of its plans for development. The reason for such reforms to the education system is to establish a sustainable economic development locally, while also actively playing a role in the educational community and securing its position in the region as completive. For instances, Education City, was developed by Qatar Foundation, comprises of multiple national and international educational facilities. Education City was implemented through policy innovations, as it directly supports economy, education, health, environment, and humanitarian works (Khodr, 2011). Furthermore, Education City was built to accentuate well-educated members of society that could serve and promote prosperity, therefore not only making Qatar known for education regionally, but also with respects to turning Qatar into a knowledge-producing country that can diversify its economy. This further exemplifies the country’s approach to policy, as it aims to empower all sectors within its society. Suggesting that Qatar’s polices are not shaped but singular objectives, but to have wide reaching and long-term impacts.

2.3. Natural Resources and Energy Sector

Qatar’s foundations and economic growth has been shaped by its production of oil and natural gas reserves, including how it implements polices. For most of its existence as a sovereign state, Qatar has strived to be independent in its foreign policy. With respects to its gas policy, this has been shaped by the wider prism of Qatar’s regional significance and by historic events in the region. During the Iraq-Iran war, each nation deliberately targeted oil tankers in the Gulf region. This promoted Qatar to move away in terms of how it operated under Saudi Arabia’s leadership and influence. After the “tanker war”, Qatar began to construct more independent foreign policies, including forming its own relationship, and trade connections with neighbouring countries, including Iran (Peterson, 2006). Qatar’s energy policy is linked to historic events, as it observes current happenings and attempts to succeed in meeting long-term sustainability. As part of its sovereignty, the state began to enhance its national identity. These efforts are seen clearly in the traditional celebrations the Energy sector is hosting in its international events. Since 1990s the presentation and demonstration of the Qatari cultural heritage and identity were always in the Energy sector international programs. Therefore, Qatar’s policies are all shaped by current events and how to anticipate change, while having full control in its actions. It can be argued that Qatar’s heritage policy is motivated by current events and how the nation can protect its continuing and lasting goals.

Thus, in the three above sectors heritage is included as a side result instead of becoming the main sector.

3. Qatar’s Refocus On Heritage Policies

Heritage policies are beneficial and rewarding when implemented correctly, as conservation of heritage can provide immense gains. This includes improved community image, as Qatar is becoming an international hub for education, sporting events and tourism, people will want to understand the Qatari people and its ancestry. Therefore, by providing tourists with points of interest to visit would enrich their experience and Qatar’s image. This would connect Qatar to the wider world and allow people to understand its culture (Timothy, 2011). In promoting heritage plans, policies, and efforts, Qatar would also benefit from economic gains in the form of increased tourist visits, which would be valuable for retail, hospitality, and transport sectors (Ashworth, 2014). Furthermore, heritage polices also provide social purposes, as residents would be better knowledgeable of their own background and history.

Qatar has implemented key changes in its 2030 National Vision, this includes promoting its heritage. By promoting heritage polices future generations would be passed on with the tools, facilities, and knowledge needed to maintain and preserve their heritage and cultural identity, thus providing a greater social benefit (Salazar & Marques, 2005). Also, there are environmental benefits that can be accomplished through heritage polices. Conserving buildings and sites rather than demolishing them reduces landfill waste, energy use, and overall pollution (Keitumetse, 2009). People like to live near or visit areas that are historically significant or naturally appreciative.

The State of Qatar has over the course of its independence begun works to establish many important strategies and objectives in order to transform Qatar into an important cultural destination for both international travellers and locals residing in Qatar. Over the years, the country has established a number of cultural events, using local universities to provide seminars, lectures, and workshops. Furthermore, local galleries and museums have also worked towards widening Qatar’s heritage. Along with establishing cultural facilities and events, Qatar also has a strategy in place where it promotes heritage by documenting and collecting folklore materials and archiving these documents. By reviving and organising documentation, that encapsulates national events and occasions, this program is being run by Qatar National Library (Henkel et al., 2018).

Through the Ministry of Culture and Sports, Qatar sponsor’s cultural events, these events include various exhibitions, workshops and training in Gulf culture and its heritage. The ministry focuses greatly on the arts and cultural movement, nationally and internationally. Such programs are mostly conducted in Katara, also known as the cultural village (AlSuwaid & Furlan, 2017). Centres such as Katara actively track the etymology of Qatar throughout its history, providing interesting and useful data regarding Qatar’s educational and cultural wealth. Cultural richness plays an important role in the building and promoting of a society.

However, although Qatar is active in promoting heritage, there are aspects that need to be improved with regards to its approach to heritage policy. There is a need to develop a centralised model that can be adopted by key governmental departments and institutions. There are challenges for many countries in terms of heritage policies. This includes fostering training and research programs, providing long-term investment to promote heritage, and involving experts and managers who can effectively implement changes (Throsby, 2007). However, as the country expands, guidance in its policies to expand institutes is also needed to accommodate the growing population. Meanwhile there is an urgent need to develop heritage policies, which would safeguard cultural heritage to face the speedy increase of diversity within the community.

4. Why Safeguarding Cultural Heritage Is Important?

The need to reserve cultural heritage remains to be of great concern worldwide, it is a critical duty of all nations. The UNESCO upholds heritage protection as a universal issue (Aggett & Van De Leur, 2020). In 2013, UNESCO designated Al-Zubara, “the Pearl of the Past” Qatar’s largest heritage site, as a World Heritage Site, which gives the area a significant value. Such designation and heritage protection works to augment national pride and strengthen a sense of local community (Aggett & Van De Leur, 2020). What cultural heritage means to Qatari authorities is preserving Qatar’s national heritage and enhancing Arab and Islamic values and Identify (Planning and Statistics Authority, 2020).

Whyton (2016) states that cultural heritage states are continuously challenged, bound up with notions of belonging, remembrance, tradition and cultural values and the politics of history, power and possession. In this view, cultural heritage is being a continuance process and linkage from the past to the present. Whyton (2016) argues that all elements of heritage are intangible, which makes the concept of cultural heritage a socially constructed notion. As societies, we allocate importance, value, connotation, and nostalgic sense to monuments or objects. This definition is vital for our analysis when thinking about safeguarding forms of cultural heritage.

Over the last few years, serious heritage scholarships have arisen as a distinct yet diverse sub-field that asks critical questions related to traditional approaches to heritage practice, studies, and theories as an interdisciplinary area (Sterling, 2020). There are key apprehensions related to the democratization of heritage, the positioning of people over things in the management of cultural heritage, a turn to marginalized societies, narratives and cultures in explaining what heritage is and its role in the world. This raises certain questions towards the work done in maintaining heritage, which cross into areas such as cultural interpretation, tourism, museology, site and monument management, conservation, archaeological studies, architectural preservation and various more official and unofficial ranges of research and practice (Sterling, 2020; Thomas, 2017). This influences the idea of heritage-fishing critiques that rose during the 1980s and 1990s studies. Such studies viewed heritage as part of a colonizing force, created in Europe and spread all over the world, to drain the past from its historically significant and to simplify cultural heritage (Sterling, 2020). However, thinking analytically about heritage and moving beyond this concept, widens the limitation of heritage knowledge. Social challenges require knowing how cultural heritage is connected to today’s communities, as well as to know how to understand, discuss and practice heritage. Especially when considering the way in which value and meanings are assigned to different cultural materials. It is also important to ask what forms and materials should be preserved and protected and what should we disregard in cultural heritage. For instances, objects, places, rituals, traditions, and behaviors, as some materials and their valuable meanings associated with specific social movement and mobilizations. However, moving away from this critique, it is undeniable that heritage is a critical factor in important issues facing societies today, including judicial systems, human right, inequalities, and sustainability (Winter, 2013). This means protection of cultural heritage is heavily based on the social world rather than the characteristics of cultural materials, objects, or sites (Smith, 1970; Byrne, 2004, 2008). Similarly, heritage has a role in forming social constructions. Such thinking proved its efficiency in developing new understanding and appreciations of the role of the past in current social life. Within this developed form of heritage analyses, heritage becomes an intersubjective idea, created through discourse and representation that has no base. In this regard, we shall question the way that heritage value is erected through people progressions of meaning-making. As such process might have a double edge, in one hand it could empower people, their belonging, roots, transmission of their heritage, heritage continuity and heritage change. On the other hand, it could develop a criterion that further marginalizes and excludes group/ groups of society. This is because heritage is viewed as a cultural practice and process rather than experience and meaning that are inherited in materials (Byrne, 2004).

Rodney Harrison has defined heritage as an interactive, dialogical, and discursive process, where the past and future grew from an encounter between numerous personified subjects with the present (Sterling, 2020). Furthermore, Christina Fredengren proposes that rather than looking at heritage from a social constrictive point of view, we should look at it as a phenomenon that crossing areas of human and non-human worlds (Sterling, 2020).

Peering in mind the above analyses, it becomes apparent that keeping a strict ideology and criteria between what should and should not be preserved is part of the cultural policy that the Qatari government should ensure as a strong heritage constitution. We understand that safeguarding cultural heritage can be achieved through the creation of Policies that control, role heritage and cultural production and consumption.

It is important to note here that such policy will provide a significant help in the forward movement of the country’s modern history. As well as it worth knowing that the importance of safeguarding cultural heritage is imposed by the nature of today’s globalization. As there is no doubt there are some social and political impacts that driven the need to protect and re-use cultural heritage. We will focus on two closely connected factors, social change, and globalizations. It could be said that this change is a result of a large economic development. Indeed, the country is witnessing an acceleration in development and social changes. An important event in Qatar’s history is happening in 2022, which is the World Cup. This event led the country to construct infrastructure, transportation system, hotels and stadiums. That became a lifeline for Qatar’s employment strategy and economy. Today Qatar facing an imbalanced demography, resulting the Qataris becoming minors in their own country. Opening the country widely to the globe, with such demography has threaten local cultural heritage. In which it is dropping into disrepair and Qatar Museums is currently seeking to initiate policies that protect and safeguard local heritage. Such policy is initiated through a collaborative work between Qatar Museums and University College London (UCL) in Qatar.

5. Impact of Economic Growth and Globalization on the Qatari Heritage

To begin, we should take account of the Qatari understanding of the terminology and practice of globalization. It is necessary to observe how that term is capable of resonates positive and negative impacts and meanings. However, it is also useful for our understanding to know how the Qatari government utilizes such term and practice positively. For the Qatari government, globalization means being an active and positive contributor and well renowned universally. This means developing various policies related to the country’s practice globally and locally, such as adopting new ideas, creations, and machineries. According to the Qatari Planning and Statistics Authority (2019) in 2018, the State of Qatar spent 4.8 billion QR in 2018 on cultural commodities. This includes a wide array of items, including visual arts and crafts, performing arts and celebrations, books and the press, cultural and natural heritage, audiovisual and interactive media, and creative design and services. This demonstrates Qatar’s dedicated economic dedications regarding its expenditure towards furthering cultural activities and placing resources into its own heritage projects. Serving both nationals residing in the country, but also creating more reasons for tourists to visit.

Nonetheless, opening the country widely to the globe has created several problems for the Qatari heritage. This becomes in precise moment in time when Qatar reached a point of reconsideration about its place nationally and globally. The main problem that faces Qatari heritage is that most of the cultural heritage is unarchived and undocumented, which means it needs to be recovered by documenting and archiving. Qatari government literally needs to go back and try to recover its cultural heritage, either physically or orally. However, such process of recovering and interpretation might include a danger of distorting and damaging forms of cultural heritage that the country aims to preserve. As the process of cultural heritage interpretation sometimes helps the rise of a new form of heritage. Particularly if we consider the influence of the rhetoric of globalization within the restoration of the heritage. Then nostalgia and heritage interpretation could result in innovating multiple heritage values and meanings (Al-Mulla, 2013). That develops further, and continues to change interpretation, presentation and ordering of things (Spivakes, 1988). For instance, the culture, heritage and history that will be introduced through the reinterpretation and reordering of museum narratives, objects and collections, the construction and reconstruction of architecture, of monuments, of sites, and the reordering and interpretation of every day rituals and objects (Foucault 1994; Paul, 1991). Such process could create an imaginable and hybrid culture; thus, cultural heritage would not be an intact heritage. Rather the creation of new heritage form would rias contradiction and tension within the community as new ideas and thinking are introduced in a paradoxical way (Baudrillard, 2005; Al-Mulla, 2013). Apparently, we need to be very careful in thinking and rethinking our cultural heritage and history and we need to be conscious of ourselves within that rethinking. Globalization has placed the concept of Qatari cultural heritage into a broader context, but one needs to recognize what concepts have or have no origin in the Qatari heritage. Unfortunately, there is a conception in Qatar today that what we are looking at and experiencing, it is a genuine Qatari heritage, whereas this is contrarily untrue. What we are experiencing is an interpretation and reordering of things, such as reordering of Souq Waqif, Souq Wagif Al-Wakra, reordering of the identity narrative at the National Museum of Qatar, reordering of the cultural materials at the same museum and reconstructing, ordering and consuming of the historical sites in North Qatar (Baudrillard, 1981; Al-Mulla, 2013). More recently, under the theme “New life for Old Qatar: Reviving Historical Areas”, Qatar Museums adopted a conservation planes that wishes to restore, reconstruct and preserve Qatari architectures, old towns and villages in the North, South and downtown Doha. For example, in Al-Ruwais, Al-Shamal, Abu Dhelouf, Al-Mufair, Sumaisma, Al-Wakra, Dukhan and Doha a number of significant historical mosques and houses were restored. The plan aims to make these sites accessible for tourists and future generations as inspirational sites to explore the ancestors’ civilization (Qatar Museums, 2020).

Ever since the economic growth, which has started from 1970s onward the socioeconomic situation for the Qataris has changed too. The remarkable economic evolution, along with the emphasis upon becoming modern have changed the concept of materials among the community. Adoption of new lifestyle became a marker of social status. Along this economic development, social structure of the country, continued to change till today. Qatar is home to several nationalities, who encompass the enormous majority of its population, with Qataris being a minority for decades. Recent statistic of 2020 shows that the total population of Qatar has reached 2,882,613, with only 333,000 of Qatari, which is only 10.5% of the total population (World Population Review: Qatar Population, 2020; Snoj, 2019). The process of the socioeconomic development and changes has destroyed different aspects of the Qatari organic cultural heritage. Pursuing the ever-modern lifestyle, technologies and complimentary was for the Qataris as a recognition for themselves in the modern world, which dominated hugely by the new (Walsh, 1992).

All those factors signify a damaging outlook for the future of the Qatari cultural heritage and tradition, which suggest that the loss of the local cultural heritage, materials and tradition in its organic form could develop further unless the country takes instant action in order to restore, preserve and maintain its cultural heritage among current and forthcoming generations. Mindful of the significances of that, recognition of the importance of national cultural heritage has been raised by the government and this has been reflected in the recent agreement that assigned between Qatar Museums (QM) and University College London (UCL). QM and UCL collaborate along with partners, such as the UNESCO, Qatar Foundation, educational organizations in Qatar, private collectors, and private museums, to develop Cultural Heritage Law of the State of Qatar. The law is to safeguard the tangible and intangible cultural heritage and materials. The establishment will update the current legal framework to comply with the approved international standards. It will focus in the following subjects: reordering the tasks related to the movement of cultural property, heritage registration and protection in Qatar museums; updating policies and legislation related to cultural heritage; providing the necessary means to preserve the integrity of heritage movables during their entry and exit from the state and establishing a specific mechanism to regulate the creation of private museums, which will be a major support for the cultural tourism sector in Qatar (Qatar Museums Archive, 2020).

Therefore, a belief in the importance of the heritage as a material culture and history, which emotionally and visually characterizes the national identity, is emphasized in Qatar in the second half of the 20th century. Currently to minimize the negative impact of economic growth and globalization, in terms of efforts made by the government, a strong emphasis upon “Qatariness” is always considered in every development the government seeks. Hence, developments of consciousness of the past and cultural heritage materials and the exercise of protecting and representing it mark a key element of today politicians’ policies. There is a believe that the spirit of the past enhanced by the new urban mass, is an important element that must be considered. Kevin Walsh says that society has what he refers to as “the organic past” (Walsh, 1992: p. 11). Accordingly, there has been a drive to reconstruct, represent and recreate the spaces that reflect this organic past.

A construction and ordering of things that present a sense of the spirit of the places or objects, could be considered as an organic form of history and heritage. It is a recognition of the vital contingency of the past extension on present places. Those physical figures have the ability to make the time through their power of possessing the past within themselves. Especially for people who know and experience them, it provides a special strong nostalgic meaning and values (Walsh, 1992).

6. UNESCO Polices in Practice

In terms of how culture is protected in modern history, in 1947, Julian Huxley, UNESCO’s first chair, stated that the main objective and purpose of this new organisation was to transcend beyond religious and political differences, in order to promote non-materialism, world humanism, and evolutionism (Huxley, 1947). Huxley further explains that UNESCO would be faced with the issue of constructing a unified pool in which policies and procedures can be adopted in each country (Shepherd, 2006). Therefore, it is important to look at case studies that has emerged regarding culture heritage in different countries.

In each scenario that involves the protection of national treasures, this includes UNESCO World Heritage Sites and artefacts of significance, there are procedures that should be followed in order for governments to effectively protect their heritage. However, there is difficulty in having a uniform means of procedure (Campbell & Smith, 2011). For example, the Mosque-Cathedral of Co’rdoba, Spain, in 2010, a group of Muslim tourists visited the site and attempted to pray, and were confronted with guards calling the police, leading to two arrests. Religious intolerance represents a threat and issue that is difficult to address in policymaking. However, to adequately preserve and promote heritage sites, heritage values and openness need to also be protected (Monteiro, 2011). Spain is a primary contributor to world heritage as it provides funds-in-trust in stimulate the protection and promotion of heritage, donating and working closely with UNESCO. However, is clear that policy makers in Spain would need to consider whether discrimination is affecting its ability to preserve and display heritage within its borders.

Another case that has identified difficulties in maintaining heritage and following procedures laid out by UNESCO was conducted by Mitra et al. (2012). UNESCO declared world heritage status in Indian Sundarbans, which is known as one the world’s most productive and diversified ecosystems. However, despite this, the site is faced with challenges that threaten the ecosystem residing in this site. This includes urbanization, increased anthropogenic activates and industrialisation, with heavy metals also contaminating the shrimp found in the site. Therefore, due to the pollution and urbanisation, a food source and heritage site is negatively impacted (Liritzis et al., 2015). This investigation suggests that even if a site has World Heritage status, does not fully protect it from human interference. This would call for two possible solutions: 1) greater government involvement, 2) UNESCO changing its policies to better protect heritage sites. In India, there are two key UNESCO offices, and the country is committed to adopting the organisations mission in addressing emerging social and ethical challenges (Meskell, 2018). However, economic development can pose an issue and would demand for Indian officials to reconsider in making its heritage laws more effective. Furthermore, this suggests that in practice, each country has unique obstacles that UNESCO polices cannot account or provide a solution for; governments need to be me more proactive in its enforcement of heritage protection, development and sustainability (Liritzis and Korka, 2019).

7. Proposing a New Model for Qatar’s Heritage Policies

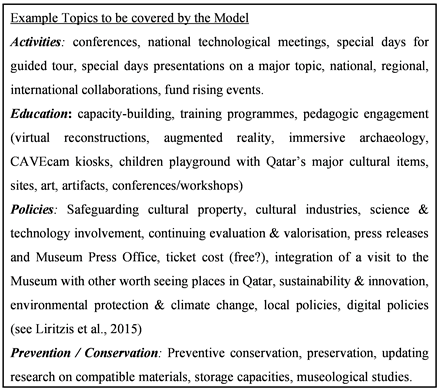

As stated above in the current context of Qatar’s plans for development, the country is experiencing changes in its demographics, resources, culture, and socioeconomic shifts that can threaten heritage (Labadi & Long, 2010). By developing a model dedicated towards heritage policy, goals such as identifying, protecting, and transmitting to future generations the Qatari culture, the country will become more efficient in achieving its goals associated with heritage. This model will be a critical endeavour in sustaining development. The proposed model is based upon four distinct areas: “Activities”, “Education”, “Policies” and “Prevention”. Below we describe this exemplary model in a qualitative and quantitative manner.

7.1. Activities

This model must meet Qatar’s needs and be tailored around the culture and future goals. Therefore, in this model “Activities” will refer to many aspects, including the implementation of national and legal capabilities in developing and collecting cultural products. With this regard, the government must act as a Secretariat. What is more, this aspect of the model would support heritage policy in Qatar, as it would encourage institutions and centres to promote events and other activities that would stimulate interest. Through this model, centres and institutions would aim to meet annual event goals using technologies available to them, while taking into consideration variables such as funding and size.

7.2. Education

Another key aspect of the proposed heritage policy model for Qatar will be education. Delivering technical and scientific understanding, and training programs, are well known factors in promoting and developing heritage policies. By providing the society with a greater prospective in how to identify issues or dangers to culture and/or stimulate heritage knowledge, the society will be better equipped with the tools needed to promote heritage in Qatar. Bertone et al. (2019) states that systematically integrating heritage in all education institutions plays an important role in fundamentally reflecting on the cultural and heritage dimension of its goals, which is important to better adapt to the ever changing society. This can be achieved through governmental support and providing a team specialised in providing training in areas of interest, such as museums, schools, universities, and sites of significance, this is known as “capacity-building” (Howard, 2015). Schools and universities will play an especially important part in getting students and young academics to be interested in Qatari culture. Therefore, in this effort involvement of the Ministry of Education and Higher Education in order to review current teachings of culture and heritage is necessary. Furthermore, technologies such as online resources should also be implemented, as this is a growing method used in heritage education (Ott & Pozzi, 2011). The educational-pedagogic engagement also concerns the protection at-risk cultural heritage (Pavlidis et al., 2018)and this also should form part of education dimension.

7.3. Policies

Another important part of the proposed model is policy. Governmental enforcement is one of the first defence safeguards against the illicit trafficking and restitution of cultural property (Hayes & MacLeod, 2008). The polices are needed to combat against individuals damaging or developing over areas of interest. Furthermore, polices also help in preventing the sale of objects deemed culturally significant (Tuan & Navrud, 2008). Also, heritage polices can be used to promote, raise awareness, educate, and inform the public and professionals alike. Currently in Qatar, there is the Ministry of Culture and Sports, which aims to achieve a balance between cultural heritage and the preservation of value systems. The current proposed model can be adopted by the Ministry of Culture and Sports to support a strong base for different cultural industries. Specifically, the ministry would need to establish a step-by-step protocol to effectively implement procedures to promoting heritage and culture. This can begin with reviewing current and new policies and procedures, gaining feedback (either internally or externally), testing and changes with a limited audience, and finally ratifying and implementing (Parker et al., 2015). Furthermore, polices can extend the promoting, educating, and raising awareness to make the public and other professionals more educated about Qatar’s heritage.

7.4. Prevention

Lastly, a core component of the proposed model for Qatar’s heritage polices will be “prevention” this refers to safeguarding, conservation, and rehabilitation measures that will assist in developing techniques, as well as conservation tools within Qatar’s academic institutes and libraries, museums, galleries, and any other place of interest/exhibition. By focusing on areas that provide education and display arts and cultural heritage, Qatar will be able to provide education, while also preventing the culture from becoming irrelative or less relative in the Qatari society. The model would be implemented by mandating that each centre will have a set of policies and list of resources that will be reviewed by the government and detail how they safeguard, conservative and rehabilitate culture, with the goal of preventing the loss of heritage and artefacts. This would also highlight any issues that the institute or centre might be experiencing and make it more effective in seeing what resources are needed.

8. Discussion

Cultural heritage enriches the individual lives of citizens, is a driving force for the cultural and creative sectors and plays a role in creating and enhancing people’s social capital. It is also an important resource for economic growth, employment, and social cohesion, offering the potential to revitalize urban and rural areas and promote sustainable tourism.

While policy in Qatar is primarily the responsibility of the Ministry of Culture and local authorities, the State is committed to safeguarding and enhancing Qatar’s cultural heritage through several policies and programs.

Thus, the cultural heritage (tangible and intangible) should be supported by a range of State’s policies, programs, and funding, much like in EU.

From our abovementioned model, a new agenda should consist of three strategic directions, with specific objectives corresponding to social, economic and external dimensions. Hence such policy will protect, produce social cohesion and a regional example for treating cultural traditions and remains in terms of identifying our cultural heritage.

Social

Aimed at harnessing the power of culture and cultural diversity for social cohesion and well-being, the agenda seeks to:

● Promoting the cultural potential of all Qataris by making a wide variety of cultural activities available and offering opportunities for active participation.

● Promoting the mobility of cultural and artistic practitioners and eliminating barriers to their mobility.

● Protecting and promoting the cultural heritage of Qatar as a shared resource, raising awareness of our common past and values, and reinforcing a sense of common Arabic identity.

Economic

With the goal of supporting culture-based creativity in education and innovation, for jobs and growth, the objectives of the agenda are:

● promote the arts, culture and creative thinking in formal and non-formal education and training at all levels and in lifelong learning

● foster favorable ecosystems for cultural and creative industries, promoting access to finance, innovation capacity, fair remuneration of authors and creators and cross-sectoral cooperation

● promote the skills needed by cultural and creative sectors, including digital, entrepreneurial, traditional and specialized skills

External

The goal is to strengthen the Qatar’s international cultural relations through three objectives

● support culture as an engine for sustainable economic and social growth

● promote culture and intercultural dialogue for peaceful inter-community relations

● reinforce cooperation on cultural heritage

Based on experience gained from other States cooperation (in EU, USA) on culture over the last decade, the new agenda is driven by strong cooperation with Member States and stakeholders, including civil society organizations and international partners. Establishing the Qatar cultural heritage entities and related actions may subsequently trigger Arabic States to define their priorities for cultural policy making at the Regional level in multi-annual Work Plans adopted in form of conclusions by the Council of the Arabic World.

Based on the core cultural heritage policy model with the above described four dimensions, we would rather propose six priorities for Qatari Museums aiming at local and Arabic cooperation in cultural policymaking:

● Sustainability in cultural heritage

● Cohesion and well-being

● An ecosystem supporting artists, cultural and creative professionals and Arabian content

● Gender equality

● International cultural relations

● Culture as a driver for sustainable development

More key topics and corresponding actions can be defined under each of these priorities, of course, taken by the presidencies of the Gulf Cooperation Council as well as Arab Cooperation Council (ACC) and making active the Cooperation agreement with European Union.

The arts and cultures bridge the gaps between peoples reinforces security perspective, and the perspective of earlier alliance and security shield of GCC. Any past and current apparent coalition must be based on strong foundations of common cultural roots. Qatar’s initiative to safeguard its heritage with a model Museum and local poles of culture and arts branches (tributaries), leads to cultural exchanges through cultural understanding to better understand what unites and divides its members. Such a model for the Qatar’s cultural policy is also distinct in taking an interdisciplinary approach of examining the political, economic, and security dimensions of GCC cohesion.

For all these reasons it is of extremely significant importance for Qatar to create a cultural heritage policy; and such policy contains basic principles in a holistic approach, which it turn protects cultural heritage for a country.

Qatar Museums along with University College London have taken the responsibility of a 10 year agreement (that ends December 2020) to develop a law that contains policies for safeguarding cultural heritage. However, the limitation of this study was the shortage of information we have about what policies will be established and how these policies will be applied in practice to ensure the protection of Qatari cultural heritage.

Practical and essential data emerge from the proposed integrated model with a indispensable clue: the tangible (material culture including monuments, remains of structures, artifacts, rock art, daily objects, scripts) and intangible (traditional music and dancing, calendars through observational astronomy, diet/gastronomy, techniques of navigation, agricultural cultivation/fishing, myths, oral traditions et.c) heritage should be preserved. Essentially all cultural life should be ideally preserved, even the modern development which is the past of the future generations, and these could be preserved on a digital repository. Therefore, we think that for essential, quality and practical reasons this is the right time to implement a new model for cultural policy in Qatar, since, “nothing is as powerful as an idea whose time has come” (Victor Hugo, French writer and poet, 1802-1885). The anticipated outcome would be beneficial to the local society, a peace-maker with neighbors and with an international spirit in practice; hence Qatar emerges as an exemplary nation where documentation and preservation of cultural heritage provides the cultural roots in a spirit of coalition with the region, showing the way of development with ethics and harmony, constructing a balanced status between people, environment, education, regional and international relationships for the benefit of all stockholders and especially the local population, bringing attention to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) for a world and life of values-driven global balance. Our proposed model is aligned to a deliberate attempt to reach a rational and enduring state of equilibrium by planned measures, rather than by opportunistic chance of temporal wealth, and must ultimately be founded on a basic change of values and goals at individual, national, and world levels (Stückelberger, 2020).

9. Conclusion

Considering the socioeconomic growth and change, the state becomes conscious of the damage that might face its cultural heritage. Hence, restoration, reconstruction, and conservation planes of historical architectures, sites villages and towns initiated by Qatar Museums. Yet, integrated policies applied to all cultural entities and stakeholders in Qatar are still missing.

Nevertheless, we should remember that Qatar’s expansion of trade, industry, politics, sport and culture has made it an active member in the international community and widened its goals to be further involved with the rest of the world. As the country further develops, polices must also change to accommodate growth while adapting to challenges. Globalization has played a significant role in shaping the country, its foreign policies and other international affairs.

The proposed integrated heritage model for Qatar will be valuable in maintaining its heritage, while also adapting to future challenges and enhance regional and international cooperation and peace. Activities will be important to furthering its pursuits in terms of artifact collecting and increasing events while also accounting for funding. This factor in the model is important to increase the production of cultural activities in Qatar. However, it is important to take into consideration that this would not mean diversification in the activities themselves, this should also be considered.

Another key aspect of the model is education, this would provide training, technical advancements, and promotion of knowledge. Educating more on Qatari heritage would also make individuals within the society more aware of the culture, while also being able to become critical thinkers and identifying potential threats to the heritage. This factor would require increased government spending on education to properly achieve higher certain goals.

Policies themselves play the core major role in the proposed model. Direct government involvement will be vital in promoting heritage polices. Policies are needed to prevent the theft or damage to artifacts or sites of interest. They can also act to promote the awareness or educating people about heritage reforms. With respects to Qatar, the policies themselves will need to be in line with government approval and this can be time constraining.

Last but not least, prevention is important in terms of identifying measures to prevent any negative impact to Qatar’s heritage. This model supports the need to provide guidance for various centers and institutions in Qatar and be involved with government agencies to oversee prevention proposals. However, this factor may face challenges in implementation, as an entire division or workforce would be needed to oversee prevention being actively adopted.

Qatar is in need of a centralized and multifaceted heritage model, an aegis to Qatari heritage and society. The development of Cultural Heritage Law in the State of Qatar becomes as a rescuer just at a challenging time that the country witnessing. This would serve the countries short-term and long-term objectives, while also meeting its national objectives and opening up more internationally. This heritage law can be adopted and implemented by government agencies and culturally relevant branches of the Qatari government to further meet its 2030 National Vision.

Notes

1) https://www.qm.org.qa/en/project/al-zubarah and http://www.unesco.org/archives/multimedia/document-2125 accessed on 2020.

2) https://www.qm.org.qa/en/project/new-life-old-qatar.

3) https://priyadsouza.com/population-of-qatar-by-nationality-in-2017/, and https://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/qatar-population/.

4) About Cultural Heritage and Creativity on EU see: https://ec.europa.eu/culture/policies/selected-themes/cultural-heritage