Attitude of Hungarian Parents in Transylvania towards Media Phenomena (Online Abuse, Addiction) in Relation to Their Children ()

1. Introduction

So far, parents seeking for a conscious media education have regulated the online existence and media use for 1 - 2 or 2 - 3 hours, depending on the child’s age.

We have conducted this research 1 - 2 months before the outbreak of the pandemic. On the other hand, the processing and interpretation of data took place during the rampage of the pandemic and the period of adaptation to it, which greatly changes the parental attitude toward Internet and smart devices.

Since March 2020, we can witness how parents in order to educate their children are forced to compromise, to give up proven educational principles, even to dampen ideas regarding their children’s health. Somehow, they have to reconcile with the fact that the target population (11 - 14- and 14 - 18-year-old students) sit 7, 8 or even 9 hours a day in front of their PC or smartphones, to learn. Of course, all these are supplemented by the time of exchanging messages with acquaintances/friends that have become a daily routine, and sometimes solving the homework too. It is shocking, but we have to admit that students spend most of their waking hours (excluding eating time, but sometimes not even that) near an online smart phone or other electronic devices. Their effects on the development of the nervous system and the development of kids’ personality will be decided in the coming years. A narrowed life-style that neglects the face-to-face relationships is a great shift, and it would be just an illusion to think that we could adapt seamlessly to it.

In this context, the role of parents is even more valued, for they are the protagonists (sometimes the only) of personal relationships in their child’s life. Therefore, it is very important what kind of model is a parent regarding the online world and the use of media tools. What kind of model does a young person follow in the world of media, where roles are often interchanged between parent and child?

2. Theoretical Introduction

According to media sociologist Sonia Livingstone, while a decade ago researchers considered mass communication an important social circumstance; nowadays they are talking about mediatized societies. The communication media significantly influences and transforms everyday life. Mediatisation modifies people’s orientation and behavioural mechanisms. Users are increasingly relying on media that they consider to be accurate and more authentic. People entrust media with their image of reality and their own sensory experiences as well (Vajda , 2014).

Mediatisation creates a new system of socialization, since children’s knowledge of reality today includes learning how to use digital electronic devices and a conscious attitude towards it. This situation is not much different between Hungarian and Transylvanian Hungarian families, present research will illustrate it in the following.

Against the mediatized world, a big question to parents and schools is to what extent they should allow digitalization in education and of course, what position they should take on the use of smart phones at all. “One solution is for the agents of socialization to keep education somewhat within the traditional framework, to pass on cultural traditions, to preserve and nurture the conditions for intergenerational communication and continuity. The many circumstances of the mediatized world make all these quite difficult, including children and young people, who are becoming less and less interested in anything that cannot be recalled or searched using keys and the screen. Another solution is for educators to follow the words of time and adapt to the changed circumstances. For example, in several states of the USA, children are no longer taught to write by hand: students learn how to write on the keyboard” (Vajda, 2014: p. 78).

In this research, we pay special attention to harassment and abuse in the chaos of emerging new media habits.

With regard to harassment, we should emphasize that it affects those individuals who are inherently unstable or hurt. Who is confident and has a healthy self-confidence, a stable background, is less likely to become a victim, but also less likely to be an offender.

Harassment in general, online abuse in the same way is distinguished from other conflict situations by three factors (Pléh, 2015).

On the one hand, it has a great negative effect: the victim is unable to live his daily life because of the harasser’s activities. He/she mostly lives in fear, insecurity and strong frustration.

On the other hand, the harassment is not necessarily at regular intervals, still it repeats itself, the abuser regularly returns to the victim and repeats his/her act.

The third criteria are the dislocation in the balance of power: in harassment, the abusive party always has more power (has more money, is stronger, has more friends, is louder etc.), and he/she shows it during the harassment. While in everyday conflicts, parties try to find solutions to a certain situation, in case of bullying the abuser aims to exercise control over his victim. In the former situation, both parties take responsibility for what has happened, while in the latter, the victim is typically blamed.

The same three conditions apply to cyberbullying: the abuser conveys strong negative content to the abused party, repeats the activity regularly, and does all this by showing off his/her power. On the Internet, on various social networking sites they often make anonymous, faceless, offensive comments, or they share an unfavourable picture or possibly a montage of a victim of harassment.

On the virtual surfaces, it is not possible to move apart in physical terms from the bully, the abuse does not end on weekends or during school holidays either. For example, anyone can save pictures and re-upload them to different platforms, one can create as many profiles as he/she wishes and countless messages can be sent to the selected victim. If someone is harassed on the Internet, in a public interface, it is not possible to tell exactly how many people have seen the post or the picture; actually, it has much more witnesses as in the case of non-Internet abuse. Humiliation associated with abuse is more painful for children, especially if they don’t even know exactly whom they have reached with it.

3. Hypotheses

· The online bullying is a fashionable, less familiar form of abuse that parents have little or no attention to;

· Parents’ sensitivity to online bullying is greater for their children if they have experienced some form of the online abuse;

· Children do not talk to parents or teachers about the possibilities of online abuse;

· In case of adolescents, parents’ attention is more focused on limiting the time for using Internet and smart devices and preventing addiction;

· We can find parental filtering programs until adolescence;

· From adolescence, the young person is left alone in the world of media, parents’ supervision and restrictions are eliminated.

4. Presentation of the Sample, Data Processing

The sample below includes the answers of 336 parents who responded to our questions using an online questionnaire1. We have sent the questionnaire to parents at the beginning of 2020, before the global outbreak of coronavirus pandemic. The online survey covered three weeks, after that we have closed the response options. However, data processing took place in that interval when our attitude towards the world of media has completely changed and a new era of mediatisation came into force.

We have processed data using the SPSS and MAXQDA programs.

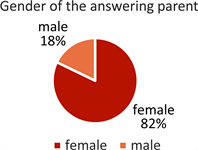

In the sample there were more female respondents; 276 female and 60 male parents have responded to the questionnaire (Graph 1).

The age distribution of the responding parents as illustrated in the first table below is quite varied. As it turned out, parents in the sample are between 18 and 50+ years old. Most of the responding parents are 40 and 44 years old, but as the table below illustrates (Table 1), a significant number (89) is between 35 - 39 years. This is followed by parents aged between 30 and 34 (49 respondents), then between the ages of 45 and 49. 21 parents over 50 responded and 9 individuals under 25. The smallest number of responding parents were between ages of 18 and 24, actually a single one.

Graph 1. Gender of the parent completing the questionnaire.

![]()

Table 1. Age distribution of responding parents.

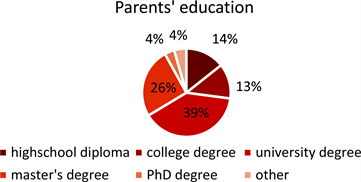

Based on the highest education of the parents filling in the questionnaire, we can say that 132 parents have university degree, 86 master’s degree, 48 high school diploma, 43 college degree, and 12 have a Ph.D. degree. 15 parents have other qualifications, which is not the purpose of this research to find out (Graph 2).

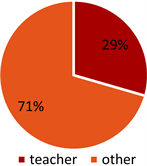

When introducing the sample, I have noted that in terms of the gender distribution of responding parents there are more women, but this is by no means a sample of teacher parents. According to Graph 3, only 29% of respondents are teachers, the majority (71%) are practitioners of other trades and professions.

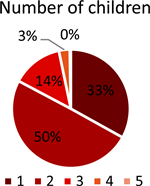

The number of children raised by responding parents is an interesting data, both sociologically and in terms of this research. We have found out that most people raise one or two children. According to Graph 4 below, 167 responding parents are raising two children—this accounts 50% of the responses, which is followed by the number of parents raising a child, i.e. 111, which is 33% of the respondents.

Graph 2. Qualification of the responding parents.

Graph 3. Profession of the respondents.

Graph 4. Percentage distribution of children raised by responding parents.

Furthermore, 47 parents raise three children (14% of respondents), 10 parents raise four children (3%) and only one family raises five children.

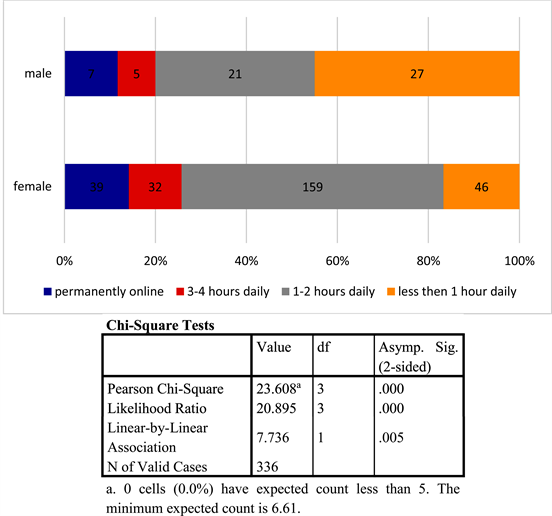

One of the basic and meaningful information obtained about the examined parent population is that we have discovered a significant difference between sexes regarding the time of the Internet use, which is illustrated in the following Graph 5.

As it turned out, women are constantly online. Women are therefore more significant as “consumer population”.

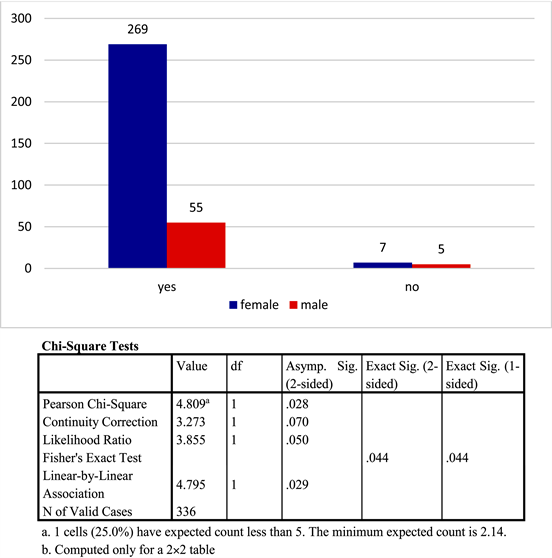

In the same way, there is a significant difference between sexes in terms of Fb account: most women compared to their male counterparts have an Fb account and they are using it (Graph 6).

In the following, we will examine questions relevant to this research. First, we have asked parents what they consider online abuse.

Respondents named harassment as the most common form of abuse, which means threats, insults, mockery, extortion and humiliation. These phenomena act differently in online space than in personal face-to-face relationships. It seems that in many cases people are more courageous, more outspoken on the online platforms, virtual space occasionally provides them protection, hiding, a stronger attacking capability.

In the context of Internet abuse, we can say that the phenomenon is already appearing among very young adolescents, children aged 10 - 12. They feel even

Graph 5. Time of Internet use in the gender distribution of parents.

Graph 6. Use of parents’ Fb account by gender.

less about the boundaries of the world of Internet or how far can one go against someone. Adopting an abusive attitude looks like an example to follow—it is considered a cool person who dares to do that. Quite often parents do not even know what is going on in the background, in other cases they don’t find the right tools to deal with the problem, because they don’t feel sufficiently prepared for the challenges posed by the online world. The online bullying, like the other forms of abuse evokes bad feelings in children, undermines their self-confidence, self-esteem and in severer cases, it isolates them from their existing friends. Children left alone become anxious and strained, and the constant stressful situation and the fact that due to harassment they cannot live their normal everyday life, can have a serious impact on their performance. They become scattered, do not perform as well as they used to, break away from their previous relationships, even the trusty relationship with parents is broken. Stress can also have long-term health damaging, mental illnesses and real physical symptoms. Adolescents can try to overcome difficulties with self-harming behaviour, they can develop eating disorders, can start cutting themselves, or in the most severe case, they can even take their own lives.

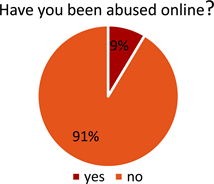

With our next question, we tried to find out how exposed the adult population was to online abuse.

As it turned out (Graph 7), low rates though (9%, 29 respondents), but online abuse occurs among adults too.

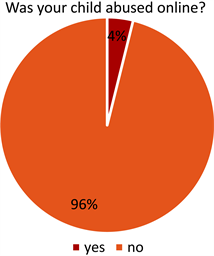

Our next question was what parents know about their children’s online abuse.

As Graph 8 shows, 4% of responding parents’ children of (13 individuals) were abused online. This data is about parents’ information concerning their children. In real life, I imagine these figures much higher. In my opinion, the child often does not tell the parent that he/she is abused, because either does not recognize the phenomenon (something that happens to be seen at home, and he/she is subordinate to it), or the abuser threatens the integrity of the parents and the child would protect his/her parents in good faith.

In terms of family background, my opinion is that infrequent parental control and the use of corporal punishments (Diamanduros and staff, 2008) increases the likelihood of becoming an offender.

Victims are characterized by low self-esteem (Gradinger and staff, 2009) and weak relationships with their classmates. Due to the excessive protection of parents, development of child’s coping skills is limited.

Our next question was about the possibilities of online abuse and its occurrence among the studied population.

As we can see on Graph 9, most of the responding parents were not involved in any online abuse. However, we have discovered that albeit to a lesser extent, but different kinds of misuses have happened among the adult population. These are comment wars in case of 58 respondents, sexual messages in 45 cases,

Graph 7. Rate of online abuse in case of parents.

Graph 8. Online abuse of responding parents’ children.

harassment in 26 cases, defamation and flattery in similar proportions (25 cases), personality theft in 11 cases and rip-off in 10 cases.

In the following, the focus shifts again from parents to children’s media using habits, to what the parent knows about all this.

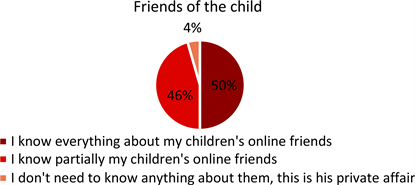

As Graph 10 illustrates, the majority of parents’ responses show that they know their children’s online friends. The “yes” answer of 168 respondents (50%) confirmed this. It has appeared in a large proportion/number that parents have a partial view of this phenomenon, this is what we learn from 153 responses (46%). 4% of parents think that online friends belong to the child’s private affairs, therefore they don’t need to know anything about them. In my opinion parents’ interest and care in this direction is also a great responsibility, it can prevent many possible hazards and problems in a young person’s life.

Furthermore, we have inquired about the content of the chats with online friends. We have found almost the same answers as in the case above. It turned out, if the parent knows the online friend, he/she also knows the content of the conversations, or if he/she knows them in part, then he/she is also partially aware of the conversations. Although we have some information about parents and their children’s online friends, chats and contents, we have asked how important is considered the parental supervision and filtering.

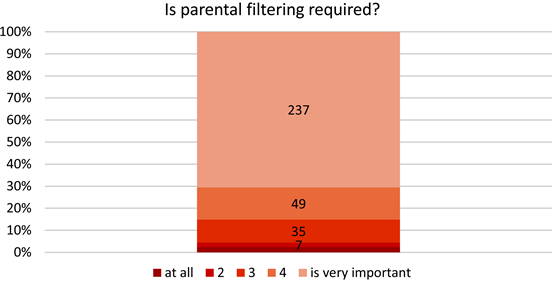

Based on the information of Graph 11 (and this data is consistent with the

Graph 9. Abuse on social media.

Graph 10. Parents knowledge about children’s Fb friends.

parental responses obtained so far), the majority of parents—237 respondents consider parental filtering very important. In the spectrum of estimated responses, moderately strong and strong positive answers are the responses of 45 and 35 parents. In only seven cases, we have found that the parent hasn’t considered important parental filtering or active presence in the use of child’s online space at all.

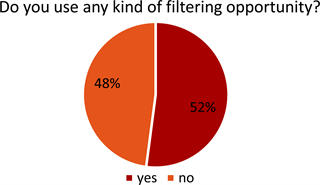

Although the majority of parents considered important to be involved and to take responsibility for the child’s online life, in the following we asked them, practically how many parents do this.

The answers show, that 175 parents use parental filtering in practice too, this is the 52% of respondents. In 161 cases, no type of parental supervision is applied, which represents the 48% of the responses (Graph 12). We consider this figure being quite high. Since we are talking about minors, it would be definitely important to support them in those activities that are challenging anyway for both parties.

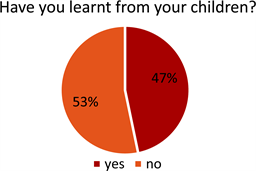

Nothing justifies this more faithfully than the following graph (no. 13), which reports that in many cases parents learn from their children (47%) and it is not clear at all that the parent actually has/would have anything to teach (53% of respondents).

Practice shoes that parents ask for technical help quite often, and in many cases, children are more proficient in the world of new applications and opportunities.

Graph 11. The importance of parental filtering, judged by respondents.

Graph 12. Parental filtering in practice.

Parental presence and help show that the child enjoys the support of the adult, who sometimes provides a better content, but emotionally definitely provides a great help.

The emotional support of parents provides guidance in the world of likes and comments hunting, a real feedback, actually a mirror in the years of adolescence or in the stage of identity development when those hard-to-digest signals of the online social interactions make a young person indisposed and sensitively affected. Children can learn from their parents how to cope with them, and of course, the stability of the adult is a great help too.

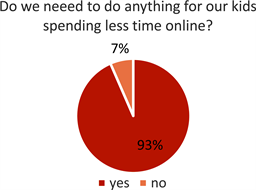

As we have seen in Graph 13, a large number of respondents agreed on parental filtering. The same is true in the context of the next question, which seeks to answer if it should be left to the parents’ discretion that kids spend less time online.

As we can see (Graph 14), most parents (314 parents, 93% of respondents) agree with the regulation of children being online, and further answers show (based on Graph 16) that they act too (91% of parents, 301 respondents) in this direction (Graph 15).

Graph 13. Parents learning about the world of media from their children.

Graph 14. Perception of parents on their duty concerning children’s online presence.

Graph 15. Regulating children’s online presence.

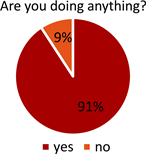

In the next step, we have asked how successful consider parents themselves in regulating and restraining their children’s online presence.

As the graph above illustrates (Graph 16), there is a quite large variance in parents’ responses to the topic. Within the spectrum “I don’t really find it successful” and “I consider it very successful”, parental responses vary widely. The majority of responses are considered very strong (79 responses), strong (99 responses) and moderately strong (103 answers), however, there are parents whose efforts are to a lesser extent (26 responses) or not fulfilled at all (18 responses).

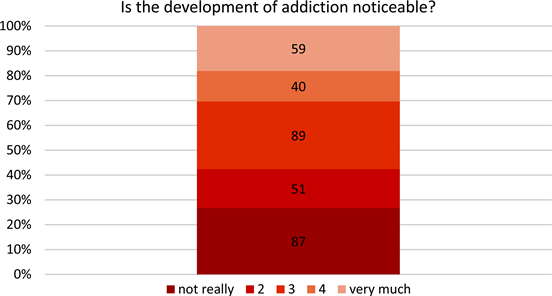

So what are the risks?

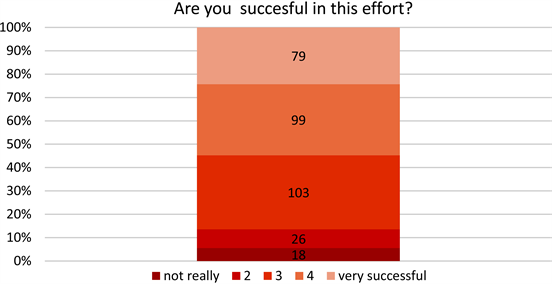

In the risk assessment, parents have identified as a primary risk the development of dependence. The list also shows that due to the access of inappropriate contents, cyberspace means risks, it can lead to health problems, it takes out time of children’s life, which parents consider an unnecessary pastime. At the same time, due to the narrowing of activities and moving away from reality, personal contacts of the young person are/may be seriously damaged.

The potential risk of developing dependence is supported by Graph 17

Graph 16. Parent-assessed success in regulating their child’s online presence.

Graph 17. The possibility of addiction, according to parents.

above. Parents rate the risk of developing addiction as moderate. However, a great number of individuals consider the virtual space to be very risky for the child (59 respondents).

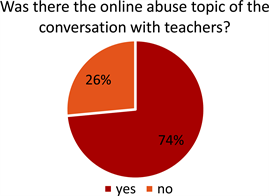

As one of the most recommended procedures in the field of abuse is prevention and informing children about facts happening online, in the following we have asked the responding parents what they know about the affected children’s education by school teachers.

According to Graph 18 above, in 247 cases (74%) parents know that their children did not have prevention activities in school, only 26% did. This data leads to at least two conclusions: if this small amount of information and discussion about online abuse and media prevention in schools is real, then we have to deal with a worrying number, and it is essential to address this issue within an institutional framework. The second conclusion is that if such enlightening takes place at school but parents do not know about it, the quality and nature of parent-school and parent-child communication is quite worrying.

In either case, the importance of discussions in this topic should be promoted and parents-school, teacher-child-parent communication should be made more effective. We need to develop a communication culture, a value to which the world of media can be called for help (I mean online communication).

Prevention would therefore be one of the possible “interventions”, where parental mediation would be a key area (Mesch, 2009).

Through parental mediation, the parent regulates the appropriate media consumption on the one hand, and it interprets contents and information seen in media. Restrictive mediation is characterized by the fact that the parent is not an active mediator; it includes tools as limiting time for Internet usage, installing monitoring and filtering software, or checking the visited websites. Evaluative mediation presumes an active parental role, during which the discussion of issues related to the use of the Internet and online content and the creation of common rules are much emphasized (Domonkos, 2014). Individual, family and functioning patterns and their disorders influence the development of aggressive and abusive behaviour. Children are influenced by the learned advocacy and management methods in the strategies that they use in their social relations, they are adversely affected by extreme patterns, such as being too strict or too permissive. (...) Children injured in their bonding, can easily become victims and

Graph 18. Dealing with online abuse prevention in school.

perpetrators. (…) During institutional socialization patterns are further differentiated. Adults that are unable to assert themselves properly and to manage conflicts in their private lives, they cannot function differently in directing the socialization of a community of children either.

5. Findings

· Respondent parents named harassment as the most common form of online abuse, which means threat, insult, mockery, extortion and humiliation. These phenomena act differently in online space than in personal face-to-face relationships. It seems that in many cases, people are more courageous and more outspoken online, also the virtual space provides them protection, hiding, a stronger attacking potential.

· Although at a low rate, but online abuse also occurs among adults. These options are comment wars, sexual messages, harassment, slander and gossip, identity theft and rip-off. 4% of respondent parents admitted that their children were abused online. This figure is about parents’ information about their children; in reality, I imagine these figures to be much higher. In my opinion, in most cases, children do not tell their parents about online abuse, because they either do not recognize the phenomenon (something that happens to be similar at home), or they are threatened by the abuser, the integrity of the parent is being attacked and children would protect their parents.

· With regard to family background, I believe that the use of infrequent parental control and corporal punishment increases the likelihood of becoming an offender.

· Parents’ attention is more about limiting the time regarding the use of Internet and smart devices and preventing addiction until adolescence. Until this age, we can observe the use of parental filtering programs, but from adolescence, the young person remains alone in the world of media, parental supervision and restrictions are completely abolished.

· 74% of respondents know that their children do not have prevention activities in school, 26% have. This data leads to at least two conclusions:

o If this small amount of information and discussion about online abuse and media prevention in schools is real, then we have to deal with a worrying number, and it is essential to address this issue within an institutional framework.

o The second conclusion is that if such enlightening takes place at school but parents do not know about it, the quality and nature of parent-school and parent-child communication is quite worrying. In either case, the importance of discussions in this topic should be promoted and parents-school, teacher-child-parent communication should be made more effective.

· We need to develop a communication culture, a value to which the world of media can be called for help (I mean online communication). Prevention would therefore be one of the possible “interventions”, where parental mediation would be a key area. Practice shoes that parents ask for technical help quite often, and in many cases, children are more proficient in the world of new applications and opportunities. However, the presence of parents goes far beyond this, helping children is about giving support sometimes in terms of content, and definitely in terms of emotions.

· The emotional support of parents provides guidance in the world of likes and comments hunting, a real feedback, actually a mirror in the years of adolescence or in the stage of identity development when those hard-to-digest signals of the online social interactions make a young person indisposed and sensitively affected. Children can learn from their parents how to cope with them, and of course, the stability of the adult is a great help too.

NOTES

1Thanks to the staff of the Hungarian Teachers’ Association in Romania, who again helped us promoting and forwarding the questionnaires.