The Utrecht District and the Disputed Territory—A Cause of the Anglo-Zulu War Re-Examined (Miscellanea)

1. Introduction

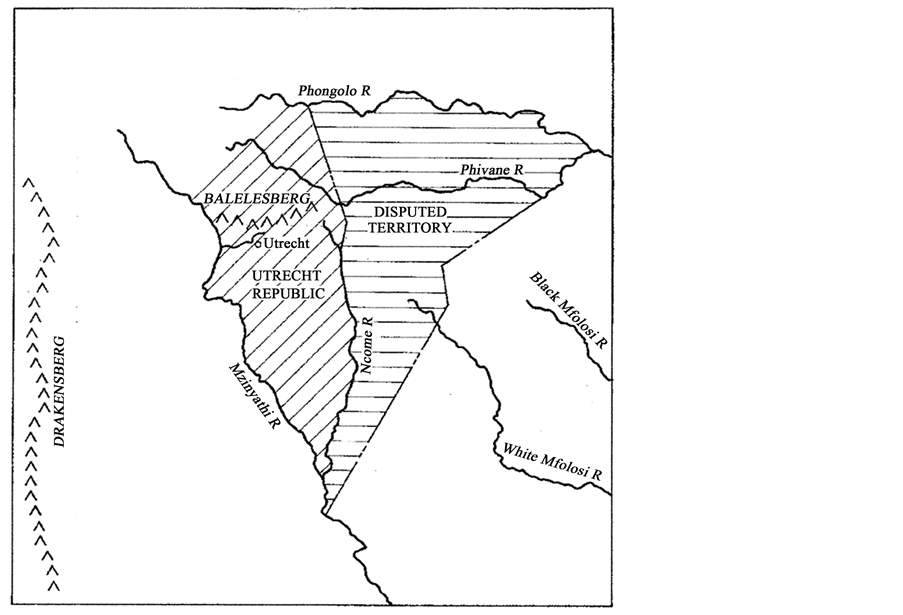

Few accounts give consequence to conditions and events that took place in the Utrecht District of the Transvaal and the so-called “Disputed Territory” in the years preceding the Anglo-Zulu War (Figure 1). Yet within these relatively small tracts of land, initially part of and bordering upon Zululand, can be found the initial seeds of contention which only later were displaced and obscured by larger political ambitions and elevated geopolitical

(a)

(a) (b)

(b)

Figure 1. (a) Southern Africa showing the rectangle enclosing the Utrecht Republic and the Disputed Territory, together with contemporary cities and states; (b) Bounding rivers and mountains of the Utrecht District, the Disputed Territory, Colony of Natal and Northern Zululand.

goals. While the underlying environmental conditions of these specific territories have been given passing attention by historians, we will examine in greater depth the character of these limitations and, in particular, show their contributory role in precipitating this conflict.

The village of Utrecht and the associated district lying between the Mzinyathi (Buffalo) and Ncome (Blood) rivers (Figure 1) was founded in 1854 following the annexation by Britain of the Republic of Natalia and the later collapse of the Klip River Republic. By 1878 the population of the Utrecht district numbered 1277 whites with an additional 248 resident in the village (Knight, 2010). Despite these limited numbers, Knight points out that it (Utrecht and the Disputed Territory) profoundly altered the dynamics of the western borders—“driven in part by the inadequacy of the pasturage, the Boers started to creep slowly eastwards in search of better grazing to be found in Zululand proper” (Knight, 2010). Laband (1995) comments that “the disputed territory remained a dangerous and unresolved quarrel between the Zulus and the Boers, and it was allowed to simmer on with ultimate tragic consequences to the Zulu Kingdom”. Cope (1999) characterizes the resulting border dispute “as the immediate cause of the war of 1879”. While Knight (Knight, 2010) quotes Bulwer, communicating with Frere, as saying “we are looking at different objects—I, to the termination of this dispute by peaceful settlement, you, to its termination by the overthrow of the Zulu Kingdom”, amplifying the contention that what had started as a land dispute was being subverted by political ambitions.

We will show that the land occupied by the Boers between the Mzinyathi and Ncome Rivers suffered inherent limitations in size, climate, productivity and carrying capacity and was not able to support their numbers. Once committed to the Utrecht District and irrespective of their farming practices, it was inevitable that these farmers would have to seek more land in order to survive. Such expansion and further encroachment upon territory already occupied by others would inevitably lead to conflict.

In addressing the loss of territory to the Utrecht Boers, Knight comments that “The loss to the Zulu Kingdom had been minimal, since much of this region was caught up in an ecosystem of its own, a combination of sandy soils and rain shadow which left its grasses unusually impoverished and made mediocre cattle country” (Knight, 2010).

These physical constraints are compounded by the turn of the 19th century by an increasing indigenous population (Wilson, 1968), and a growing complexity of emerging political groups (Brookes & Webb, 1965; Duminy & Guest, 1969; Jones, 2006).

With the exception of Jones (2006), and, in contrast to other historians who have dealt with the larger role of the environment, we specifically relate the environmental conditions of the Utrecht district to the coming conflict. In the sections that follow, we will stress the inherent limitations of a climate and environmental system which is subject to decadal lengths of dry and wet periods (Tyson, 1986; Kane, 2009; Nicholson, Dezfull & Klotter, 2012), seriously disrupted by tectonic events (Garstang & Fitzjarrald, 1999; Joseph & Zeng, 2011; Haywood, Jones, Bellouin, & Stephenson, 2013; Garstang, Coleman, & Therrell, 2014), limited by soil structure and fertility (McI Daniel, 1973; Hall, 1976; Gump, 1988; Camp, 1995), and poorly served by inadequate grazing (Acocks, 1953; Camp, 1999). Central to our thesis is thus the role played by the physical, biological and geomorphological conditions of the Utrecht District. We will, of necessity, describe in some detail the nature of these environmental constraints. Our argument hinges upon the detail of these limitations which, in turn, forced the Utrecht Boers to encroach upon Zulu territory, creating the underlying cause of the Anglo-Zulu War.

2. The Geography of the Region

The Utrecht District and the “Disputed Territory” lie between what was at the time, the Colony of Natal and De Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek (Transvaal) all to the west and north of northern Zululand (Figure 1(b)). The region is bounded by the Drakensberg escarpment in the west and by the Balelesberg in the north, which hinge eastwards towards Swaziland (Figure 1(b)). The rolling terrain of this region has its ancient origins in the sedimentation of the Karoo Depression which ended 182 million years ago (MYA) with the release of extensive lava sheets as Gondwana began to break up and the Drakensberg was formed. Continued uplift and tilting of southern Africa in successive periods between 20 MYA and 5 MYA resulted in further erosion and sedimentation. Deep but strongly leeched soils were formed with numerous short rivers, still evident today, flowing eastward into the Indian Ocean from the Drakensberg escarpment (McCarthy & Rubidge, 2005).

The region thus consists of extensive plains, bisected by rivers and streams with gentle slopes, most at approximately 5% but slopes occasionally at 12%, particularly towards the surrounding escarpment. The vegetation is mainly grassland with limited amounts of bushed grassland (Camp, 1995).

3. Climate and Soils

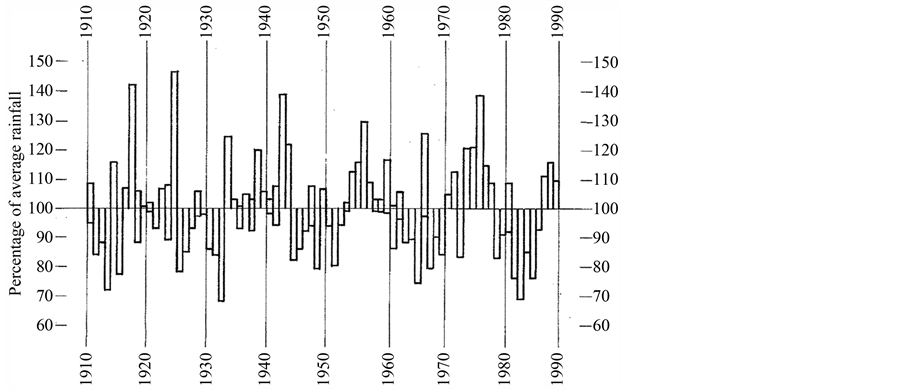

The large scale semi-permanent anticyclones dominate the climate of subtropical southern Africa. Extreme dry conditions prevail over much of the western half of the subcontinent (Kalahari and Namib deserts), while wetter conditions in the east benefit from the inflow from the Indian Ocean (Garstang & Fitzjarrald, 1999). The Utrecht district is not only subject to marginal rainfall but throughout its history, has been stressed by periodic droughts (McCarthy & Rubidge, 2005; Kane, 2009; Nicholson, Dezfull, & Klotter, 2012), and pervasive decadal length wet and dry periods (Tyson, 1986; Hobbs, Lindsay, & Bridgman, 1998) (Figure 2).

Seventy-nine percent of the annual mean rainfall occurs in summer (Table 1). Winter rains occur when the Antarctic polar systems (coastal lows) penetrate the subcontinent and progress towards the equator along the eastern seaboard. The average rainfall of the area lies between 700 and 800 mm per annum with a coefficient of variability of 555 to 911 mm (Table 1). Higher rainfall areas to the north and west of Utrecht occur over the elevated Balelesberg and the associated escarpment. Much lower figures are recorded to the southwest on the “Buffalo Flats” to the east of the Mzinyathi (Buffalo) river. In modern agriculture, dry land crops can be produced with a mean rainfall of 800 mm or higher. With a mean rainfall of 700 - 800 mm, supplementary irrigation is advised while rainfall of below 705 mm would require irrigation for crop production (Camp, 1999).

Table 1 shows the mean annual temperature of 16.7˚C (64˚F) with monthly maximum temperatures highest in January of 26.6˚C (79.88˚F). The months of June and July record minimum temperatures of 3.2˚C (37.8˚F) respectively. With minimum temperatures of 3.2˚C, moderate to severe frost will occur resulting in severe damage or loss of crops. The growing season (last frost to first frost) is, however, protracted and would apply both to crops and natural grazing (Camp, 1999).

Figure 2. Time series of rainfall from 1910-1990 for the summertime rainfall region of South Africa shown as a percentage above and below the long-term mean (100%) for each year (Hobbs, Lindsay, & Bridgman, 1998).

Table 1. The average monthly and annual rainfall and temperatures (max/min) for the Utrecht District and Disputed Territory (Camp, 1995).

Annual means: Rainfall (mm): 738; Temperature (˚C): 16.7; Min (˚C): 9.7; Max (˚C): 23.8.

4. The Soils of the Utrecht District

Soils are highly significant in the production of both natural vegetation and crops. The soils of the Utrecht District are generally poor to very poor. A breakdown of the different soil types and the relative abundance in the district shows eight soil types. Of these eight soil types, soils suitable for both cultivation and grazing cover only 21% of the Utrecht District. When combined with unreliable rainfall, frequent droughts, curtailed growing seasons (severe winters), crop failures and serious impact on pasturage would be a frequent occurrence. The remaining soils in the Utrecht District (poorly drained, black and duplex soils), fare poorly in times of drought because the shallow moisture reservoir dries rapidly. In periods of high rainfall, they would become waterlogged. Contemporary characteristics of the Utrecht District exhibit extensive areas of abandoned land (Camp, 1995).

5. Vegetation and Grazing

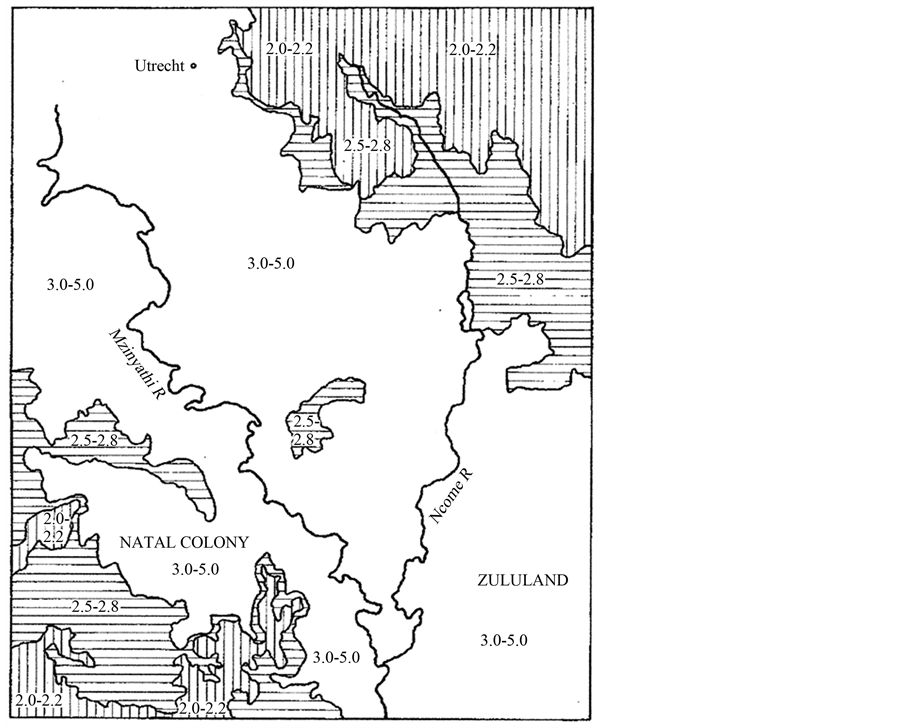

The Utrecht District lies within a vegetation type known as Sour Sandveld and is dominated by grass species associated with Sandveld areas (Figure 3).

The veld has a high proportion of poor grass species of the genus Eragrostic Sporobolus, Elionurus, and Aris-

Figure 3. Natural vegetation of the region: 1) sour sandveld (income sandy grassland), 2) KwaZulu-Natal moist grasslands, 3) KwaZulu-Natal highland thornveld, 4) Wakkerstroom montane grassland, 5) Paulpietersburg moist grassland, 6) upland thornveld, 7) Thukela thornveld, and 8) moist grassland (Camp, 1999).

tada as well as species that grow in sandy soil with low grazing value and productivity such as Trichoneura, Grandiglumis, Perotus Patens and Eragrostis gummiflua. All these grasses have a poor nutritional value, most can only be grazed for a short while at the onset of the growing season and some are so tough that grazers struggle to ingest them. Figure 3 shows the widespread distribution of these sandy grasslands across the Utrecht District and the “Disputed Territory” to the east (Camp, 1999).

Figure 4 shows the grazing capacity of these grasslands measured in units of hectares per animal unit (AU) where an animal is defined as a beast with a mass of 450 kg consuming 10 kg of dry matter per day. An AU is equivalent to 6 sheep. The grazing capacity of the Utrecht District and the “Disputed Territory” lies between 3.0 and 5.0 AU (Figure 4). Translated into carrying capacity, a farm of 500 Ha can carry only a maximum of 120 AU, which would not be economical today and would probably not have satisfied the Boer farmers of the 19th Century. Under these dry land conditions, with a calving percentage of a maximum of 70%, the farmer would have about 80 animals to dispose of approximately every 2 years. Even under optimal conditions such production is unsustainable. Required mature draught (Trek) oxen needed for general farming purposes are non-productive and place additional pressure on the grazing.

6. The Historical Climate of the Region—The Utrecht District and Surrounding Areas

The area east of the Mzinyathi River has a history of droughts. An area of sand dunes exists east of the river and fluctuates in size with periodic changes in rainfall.

Figure 4. Grazing capacity of the region in hectares per animal unit (AU), where an AU is a beast with a mass of 450 kg consuming 10 kg of dry matter per day (Camp, 1999).

Tyson (1986) has shown a quasi-periodic oscillation in summertime rainfall over South Africa with a near 20- year cycle with a variance of between 20 and 40 percent above and below normal rainfall (Figure 2) (Tyson, 1986; Zambates & Biggs, 1995).

Garstang, Coleman & Therrell (2014) and Therrell, Stable, Ries & Shugart (2006) have shown decadal fluctuations in rainfall from tree-ring analysis throughout the 19th Century.

Evidence of two prolonged droughts between 1800 and 1824 are found in Natal tribal testimony as well as proxy data on world weather conditions in the first quarter of the 19th Century. The drought between 1800 and 1807, known to the Nguni peoples as the Madlathule (let one eat what he can and say naught), caused great distress and suffering to the northern Nguni. The famine drove entire clans or sections of chiefdoms to abandon their homes and migrate elsewhere in search of food (Ballard, 1986; Eldredge, 1995).

The introduction of maize through the Portuguese traders, replacing the more drought resistant African crops, increased the vulnerability to drought to local societies. The cattle herds would have suffered from the resultant deterioration of pastures, especially in the drier interior.

In April 1815, the Island of Tambora (8.2˚S, 118˚E) in Indonesia, was obliterated in a massive eruption, some 100 times larger than Mt. St. Helens eruption in 1980. Dust clouds penetrated the stratosphere and circled the earth for more than 2 years. The year 1816 was known in the Northern Hemisphere as a year without a summer (Harrington, 1992; Oppenheimer, 2003).

Repercussions in the Southern Hemisphere were manifested in rainfall dropping below 50% of the mean, and the drought conditions, which prevailed in the first decade of the century, were extended into the second decade. It is likely that the Mzinyathi and Ncome rivers ceased flowing and cattle and other farming practices ceased or were seriously impacted.

Perhaps as serious as the drought conditions, were the severe cold winters following the eruption of Tambora which would have curtailed growing seasons, diminished crops and limited grazing for four to five years after the eruption of 1815. Grab and Nash (2010), examining cold seasons in Lesotho, state that the coldest period during the 19th Century were the years immediately following the eruption of Tambora (Nash & Grab, 2010).

While Nash and Grab were unable to document the effects of Tambora, winters following the eruption of Amagura (18˚S, 72.2˚2W) on 11 June 1846, led to three consecutive years of very severe winters and one severe winter between 1847-1850. There was extensive loss of human life and livestock in the lowland regions of Lesotho. Similarly, the eruption of Krakatoa (6.4˚S, 105.3˚E) between 26-27 August 1883, led to four consecutive years of severe winters and early frosts. The impact of the Tambora eruption is thus likely to have been at least as severe as those subsequent eruptions where the Volcanic Explosive Index (VEI) for the three events is: Tambora 7, Amagura estimated at 4, and Krakatoa at 6 (Oppenheimer, 2003).

Garstang, Coleman & Therrell (2014), document six prolonged drought periods in the reconstructed rainfall record from treering analysis in Zimbabwe (1810-1823, 1839-1843, 1855-1870, 1883-1894, 1920-1930, 1937- 1950). Three of these coincided with volcanism (1809/1815, 1846, 1883). It is likely that these droughts were reflected in the summertime rainfall region of South Africa, including Zululand.

Guy (1980) has previously noted that “there was a major famine in the region during the early years of the 19th Century during which starving marauders tried to seize food stores and settlement patterns were changed with the object of protecting such stores more effectively”. A feature of the struggles at this time was the increase in the area controlled by a single political unit.

This gave members of this unit access to a wider range of grazing and arable land, enabling them to cushion the effects of local drought and shortage, making for more effective control of the environment. These droughts may have played a major role in initiating or at the very least, exacerbating the Mfecane, during which Shaka kaSenzangakhona is said to have consolidated the Zulu hegemony at the expense of many tribes in the region (Garstang, Coleman, & Therrell, 2014).

Famine in 1852-1853 led to more severe hardship amongst the African subsistence farmers and could have caused disaffection with the Zulu King, Mpande kaSenzangakhona (Duminy & Guest, 1969). There was also a severe drought in the region in 1877, on the eve of the war, when opposition to the annexation of the Transvaal, as well as Zulu opposition to continued occupation of the “Disputed Territory” by the Transvaal Boers, was of concern to the British Colonial Administrators (Killie Campbell Africana Library, 1878).

7. Peoples of the Region

Conflicts in Northern Zululand (Figure 5) over cattle and grazing lands was intensified during the last years of

Figure 5. Distribution of political groupings in the region circa 1800-1856 showing the rivers and contemporary towns (Jones, 2006).

the 18th Century, by a change in trading patterns set in motion by European incursions into the region. The demand for beef increased due to British and American whalers calling for provisions at Delagoa Bay. As local conditions around the bay are unsuitable to cattle farming, cattle had to be brought in from elsewhere. Cattle theft was probably rife (Duminy & Guest, 1969). Within a few years, drought, population pressure, and the impact of outside forces provided opportunity and pressure for the strong to prey upon the weak. Many tribes were displaced. The powerful Ndwandwe drove the Ngwane northwards, who subsequently drove the Hlubi south into the area between the Mzinyathi and Ncome rivers (Figure 5). The Khumalo left the region to re-establish elsewhere and within the center of the region, Shaka kaSensangakhona had begun consolidating tribal groups into a powerful hegemony—the amaZulu.

Following closely upon these tribal turmoils, elements of the Boer exodus from the Cape, the Voortrekkers, entered the region in late 1837. After clashing with the amaZulu, under Dingane kaSenzangakhona, in December 1838, these “Trekkers” formed their own republic with the acquiesance of the third Zulu King, Mpande kaSenzangakhona (Brookes & Webb, 1965).

British annexation of the Boer Republic of Natalia in 1844, caused many Boers to move north over the Thukela river. Here they initially occupied a piece of land between the Klip and Mzinyathi Rivers. After objection from the British authorities, the “Klip River Republic” came to an end within a year. At this time Mpande had begun a series of campaigns to assert his authority and the Hlubi were driven from their lands between the Mzinyathi and Ncome Rivers (Webb & Wright, 1976; Jones, 2006).

It was at this crucial time (1854) that about 200 Boer families moved into the area between the Mzinyathi and Ncome Rivers, vacated by the Hlubi. This was indisputably Zulu territory and soon these indefatigable people started establishing farms and homesteads. Initially ignored by the Zulus, the area was ceded to the Boers by Mpande in September 1854, and named “The Utrecht Republic”. This small republic became part of the Transvaal Republic in 1859 (National Archives Repository, 1864).

The Utrecht Boers would have been forced to seek additional grazing within a short period. Unable to sustain themselves in this delimited and limiting area, they sought to expand eastwards into what was to become known as “The Disputed Territory”. Set within a volatile mix of people and a rapidly changing political landscape, the “Disputed Territory” increasingly became the focus of conflict (see section on Vegetation and Grazing).

Cetshwayo kaMpande, heir apparent to the Zulu Kingdom, sought to gain support by building contacts with both the Boers and the British administrators, and in many cases his diplomacy was contrary to that of his aging father, Mpande. The Utrecht Boers capitalized on these intrigues, making alliances with local chiefs and escalating tensions over the next few years (Laband, 2001).

The most significant agreement was known as “The Waaihoek Agreement”. Here, in 1861, in exchange for two half brothers who had sought shelter in Boer territory, Cetshwayo granted the Utrecht Boers an area to the east of the Ncome River, later the “Disputed Territory”. A large portion of this area was in the chiefdom of Hamu kaNzibe, powerful chief of the Ngenetsheni, leading to a strained relationship between the two (Jones, 2006). The border situation remained tense and both Cetshwayo and Mpande later repudiated the Waaihoek Agreement.

With the discovery of diamonds in the west of southern Africa, and the subsequent Keate Award, political complexities escalated to geopolitical levels. Relationships soured further between the British and the Boer republics and attention shifted temporarily away from the border issues. As part of the British plan for a confederation of states in the region, the Transvaal was annexed in April 1877 and dictation of policy shifted from Natal to the Cape to the new High Commissioner, Sir Bartle Frere. With the need to placate the recalcitrant Boers, Sir Theophilus Shepstone met a Zulu delegation at Conference Hill, near the Ncome River on 18 October 1877, to discuss the border issues. It was an acrimonious meeting. Shepstone, now Administrator of the Transvaal, tried to get the Zulu delegation to accept the “Disputed Territory” as part of the Transvaal. The Zulu delegation, under the leadership of Mnyamana kaNgqengelele, Chief of the Buthelezi, flatly refused (Preston, 1973).

Cetshwayo was frustrated and angry. The Zulu delegation had believed that Shepstone had called the conference to advise them that the land would be returned, as he had, during the many years as a senior Natal official, known of their demands (Jones, 2006).

War clouds gathered and with a threat of a border war looming, the Lt. Governor of Natal, set up a commission to rule on the matter. This commission commenced hearing evidence on 12 March 1878, and the findings were sent to Frere in July 1878. The preamble read “the evidence shows that this ‘Disputed Territory’ has never been occupied by the Boers, but has always been occupied by border clans, who have never moved their homes, and that the only use ever made of the land by the Boers has been for grazing purposes, which in itself proves nothing” (Pietermaritzburg Archives Repository, 1984).

The commission found that the Boers had the right to the land between the Mzinyathi and Ncome rivers, but the area to the east of the Ncome (the Disputed Territory) was Zulu territory. Effectively this meant that the only agreement acknowledged among the many confusing claims and counter-claims was the one of 1854, where Mpande ceded the strip between the Mzinyathi and Ncome rivers. Durnford’s map, part of the commission report, is shown as Figure 6. It clearly shows the eastern boundary of the Utrecht District and the “Disputed Territory”.

Frere was aghast and Shepstone equally so. For decades Shepstone had been able to manage Zulu affairs and supported them, even if only for his own political ends. Now he was distrusted, some accounts say, hated, by both Boers and Zulus alike, and as Administrator of the Transvaal, he was bound to support the Transvaal (Boer) claims as it was evident that his Transvaal regime depended on the support of the Boer populace. The obvious action was to remove the perceived Zulu threat to the peace and security of the region (Laband, 1995; Cope, 1999; David, 2004; Jones, 2006).

Frere decided not to act immediately and did not release the report. He then set about showing the Zulu Nation up in a bad light—in this way preparing the “moral high ground” for his plan to eliminate the Zulu military and social system and solve the problem of the “Disputed Territory” as it was imperative to keep the Transvaal from rebellion (Laband, 1995; David, 2004; Jones, 2006).

As he prepared for war, British officers were dispatched to gather intelligence. Colonel Evelyn Wood, noted the recalcitrance of the Boers when he visited Utrecht in September 1878, having been told that he could rely on about 800 Boers to join the campaign.

Figure 6. Copy of Map C drawn by Lt. Colonel A. W. Durnsford to accompany the report of the Zulu Boundary Commission dated 20 June 1878 (see note in text). Reproduced with permission of the Natal Archives, Pietermaritzburg.

He noted “on my arrival, however, I found that owing to the prevailing feeling of irritation against the Imperial Government, it was generally believed that few or none would come out” (British Parliamentary Papers, 1879a). The “Disputed Territory” was once more at the forefront of local politics.

Cetshwayo was given an ultimatum on 11 December 1878, an ultimatum that Frere (and Shepstone) knew he could not accept. On the eve of the ultimatum, Frere wrote to the Lt. Governor, Sir Henry Bulwer: “The Boers are watching what we do in our discussions with the Zulus. If they see that we are able to do what they themselves could not effect, by keeping the Zulus in check, the Boers will acquiesce with more or less equanimity, in the justice of our annexation of the Transvaal. Otherwise, they will consider this at least on the grounds we assigned, is invalid, and they will submit with a bitter and not ill-founded sense of the insufficiency of our justification” (British Parliamentary Papers, 1879b). This missive illustrates the extent to which the dissent over the “Disputed Territory” influenced events at that crucial time. The Anglo-Zulu War followed.

8. Conclusion

The Anglo-Zulu War of 1879 was subject to a complex set of geographic and geopolitical issues, no one of which can be assigned the weight of ultimate causality. At the focus of this conflict, the Utrecht District and the adjacent Disputed Territory lie within a geographic region in which rainfall, temperatures, soil and vegetation can only support a limited pastoral and agricultural community. Under these geographic conditions, the region was ill-equipped to withstand the pressures exerted by a complex mix of indigenous and alien peoples.

The marginal nature of the climate and soils of the Utrecht District are greatly exacerbated by the pervasive periodic oscillations in rainfall amplified by tectonic events which have prevailed throughout the history of the region. Cycles of above and below normal rainfall, each persisting for a number of years, impose stresses upon a fragile natural system which reverberates into the social and political structures of the region. When any one of the recurrent cycles is amplified into an extreme event, such as a protracted drought, the effect on those living in the region could have bordered upon the catastrophic.

By the outbreak of hostilities, multiple tribal entities occupied the Disputed Territory, as well as Boers who required the grazing. The Zulu leadership, anxious to assert their authority, stood their ground and refused to compromise over ownership of the area. Conflict between these groups was amplified and capitalized upon by those forces in the long standing dispute over ownership. Frere, who was influenced and advised by Shepstone, subverted the attempt by Bulwer to diffuse the tense situation. The geopolitical policies seeking to bring about a confederation, necessitated placating the Boers in the Transvaal republic.

The British government, beset with serious political issues in Europe and the East, was explicit in its directions to Frere to seek Boer co-operation. Fear that the Transvaal would receive aid from the recently unified state of Germany, added urgency to these concerns. Laband further points out in his atlas of the later Zulu wars that “Imperial Germany’s growing interest in the coast of Zululand and consequent fears of a potential link-up with the land-locked Boers of the South African Republic, by way of the nascent new Republic (Vryheid 1884- 1888), reflected the inherent instability generated earlier by the Utrecht Boers and their encroachment into the Disputed Territory, and ultimately striving for a corridor to the sea” (Laband, 2001).

Therefore, there could be no war with the Transvaal and the “Zulu Question” or “The Disputed Territory” could not be decided in favor of the Zulus. A war with them was the answer.