Genetic Parameters Estimates Associated to Conversion of Nicotine to Nornicotine in Burley Tobacco ()

1. Introduction

One of the major alkaloids produced by tobacco (Nicotianatabacum L.) is nicotine and represents 90% - 97% of the total alkaloid content [1] -[3] . During curing and processing of tobacco products, part of the nicotine may be converted to nornicotine by the enzyme nicotine N-demethylase [4] -[6] . Nornicotine is considered one of the most detrimental alkaloid once itis a precursor of tobacco-specific nitrosamines (TSNAs) [7] [8] , specifically N- nitrosonornicotine (NNN), which is classified as a risk substance into tobacco products [8] [9] (Figure 1). From this prospective, nornicotine is undesirable because it converts to TSNAs through nitrosation [10] . Consequences caused by nornicotine effects can be found in the literature [11] -[13] .

For that reason and considering that tobacco is consumed primarily in the form of cigarettes, one of the goals of a tobacco plant breeder is to develop very productive varieties keeping nornicotine levels to a minimum [14] [15] . In fresh tobacco leaves, nornicotine represents <5% of the total alkaloid content [1] , but its level may in- crease considerably by a natural mechanism called conversion, which transforms as much as 99% of nicotine to nornicotine [1] [16] .

Conversion occurs mainly during senescence and curing [17] . Tobacco varieties that convert a high portion of their nicotine content into nornicotine are referred to as “converters”, in contrast to those that retain nicotine as their predominant alkaloid-“non-converters”. Although conversion is a common process in all tobacco groups, the frequency of conversion in burley varieties is higher than in flue-cured tobacco [3] [18] .

Several studies aiming to determine the genetic mechanism underlying this process have been conducted. The first studies have shown that a single dominant gene has controlled the difference between high and low norni- cotine varieties [19] -[21] . This gene has been isolated and it was seen to encode a cytochrome P450 monooxy- genase, which is expressed during senescence and in response to ethylene treatment [3] [22] . Although this gene plays an important role in the nornicotine biosynthetic pathway, there are many other genes and regulators in- volved in nornicotine formation.

Many technologies are being studied in an attempt to reduce nornicotine produced in tobacco leaf. RNA in- terference (RNAi) has been used to induce post-transcriptional gene silencing on genes controlling nornicotine synthesis [3] [22] [23] . This technique allows degradation of target mRNA of specific sequences [24] . Another option would be to randomly insert chemical mutations into the tobacco genome and search for plants in which the nicotine N-demethylase gene is permanently impaired [23] [25] . However, the expression of other genes in plants can be altered by these two methods as a result of unknown effects of these techniques in other genes con- trolling important traits, for instance growth, or resistance to insects and diseases.

An alternative strategy would be to select plants and progenies in a conventional manner with the same effect, without using genetic engineering. Therefore, understanding the genetic control and inheritance underlying the nicotine conversion in superior varieties is important for selecting efficient methods and strategies for increasing yield while minimizing nornicotine content. This was the aim of the present study. Thus, we show the predomi- nant effect in genetic control of nicotine conversion and alternatives that may lead to a higher gain in decreasing nornicotine in tobacco leaves.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material and Field Evaluation

All plant materials used in this study were provided by Souza Cruz SA. Two contrasting burley inbred lines, TN 90 (“non-converter”) and BY 37 (“converter”), were crossed to obtain the F1 generation. F1 plants were crossed with both parents and self-pollinated to generate backcrosses (BCs) and the F2 population, respectively (Figure 2). The F1 generation was not evaluated.

![]()

Figure 1. Simplified pathway of nicotine conversion process, and structures of nicotine, nornicotine and NNN.

![]()

Figure 2. Dynamics of how generations were obtained.

Field evaluation was carried out in Rio Negro, PR, Brazil in the 2013/2014 crop season. A randomized com- plete block design with two replications was used. Different numbers of plants were evaluated per generation: 40 from TN 90, 40 from BY 37, 200 from the F2 generation, 200 from BC-TN 90, and 200 from BC-BY 37. They were randomized into the two replications in experimental units consisting of a single 10-plant row. Data was collected at the individual level.

2.2. Chemical Analysis

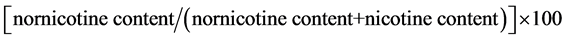

Quantitative determinations of nicotine and nornicotine in cured leaf samples were carried out for each plant in the plot. The analysis was done at the Product Center Laboratory of Souza Cruzlocated in Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil. The samples were extracted and the quantification of the nicotine and nornicotine was performed by gas chromatography. The results were reported as μg/g of leaf tissue for nicotine and nornicotine content, and as percentages for conversion. The percentage of nicotine conversion was calculated as:

.

.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Data was subjected to analysis of variance for randomized complete block design using R software [26] . The accuracy of the evaluation for all traits was calculated by:  [27] , in which F is the statistic of F-Sne- decor for treatments.

[27] , in which F is the statistic of F-Sne- decor for treatments.

Genetic components of mean were estimated using generation means (parents, F2 and BCs), through the approach proposed by Rowe and Alexander [28] . The proportion of the total variation among the generation means explained by the genetic model was obtained through the coefficient of determination (R2) and used to test the additive-dominant model with and without epistatic effects.

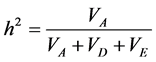

Genetic components of variance were estimated by iterative weighted least square [29] . The variance was par- titioned in environmental (VE), additive (VA) and dominant (VD). Also, the R2 coefficient was calculated to measure the variation explained by the model. The narrow sense heritability (h2) at the individual level was es-

timated using the following expression:  [30] .

[30] .

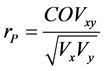

Pearson phenotypic correlation was estimated between the total nicotine content before leaf curing, and the nornicotine after curing using plants of the F2 generation by:  [31] , in which COVxy is the phenol-

[31] , in which COVxy is the phenol-

typic covariance between the traits and Vx and Vy are the phenotypic variances of each trait independently. The t

test was applied to rP to check whether the estimate is not equal to zero.

3. Results

The means of each trait for the generations are shown in Table 1 and frequency distribution in Figure 3. The

![]()

Table 1. Means and intra-generational variances for nicotine and nornicotine content, and nicotine conversion, obtained for the parents and the segregating populations of tobacco.

![]()

Figure 3. Distribution of frequency in number of individuals from F2 generation, Y-axis, for nicotine conversion (%), nico- tineand nornicotinecontent (μg/g), X-axis, obtained from crossing of tobacco inbred lines, TN 90 × BY 37.

parents proved to be contrasting for all traits, which is vital for this kind of study. The means of the F2 with re- spect to all the characters studied were approximately equal to the means of the parents. The mean values of BCs tend to the recurrent parent, as expected. Figure 3 shows a high segregation for the F2 generation, indicat- ing, initially, that several genes are responsible for phenotypic expression of the traits. The variances of the F2 generation were higher than the variances in the other generations, and BCs showed intermediate variances, congruent to what was expected.

Estimates of genetic parameters are shown in Table 2 and Table 3. The additive-dominant model explained most of the variation (R2 = 94%). Additive gene effects (a) were relatively high compared to dominance devia- tion (d), and the values were significantly different from zero (Table 2). However, the generation means de- pends not only on additive effects, but also on dominance effects in determining the trait means, although to a low degree. The estimates of the average degree of dominance (add) confirm this observation.

The estimates of environmental (VE), additive (VA) and dominance (VD) variance, as well as the narrow sense of heritability (h2) are shown in Table 3. The adequacy of the additive-dominance model was higher than 94%, indicating a good fit. The standard deviations had magnitudes lower than the estimates, indicating that both VA

![]()

Table 2. Genetic parameters estimated by an additive-dominant model with respective standard deviation; average degree of dominance (add); and R2 coefficient for three traits in tobacco: nicotine, nornicotine and conversion.

1Standard deviation.

![]()

Table 3. Estimates of environmental (VE), additive (VA) and dominant (VD) variance with respective standard deviation, narrow sense heritability (h2) and the R2 coefficient for three traits in tobacco: nicotine, nornicotine and conversion.

1Standard deviation.

and VD were different from zero. The estimated VA and VD components were consistent with a and d described before. Heritability (h2) represents another parameter that provides information about the genetic control of the trait and allows us to infer whether the trait can be easily selected. In the present study, narrow sense heritability at plant level was relatively high for all characters (>65%). In this case, h2 only represents additive genetic va- riance, which is associated with the breeding value an individual can transmit to its progeny.

4. Discussion

Quantification of nicotine and nornicotine content, as well as the conversion rate, were performed with high precision, as can be confirmed by the high experimental accuracies (>92%, data not shown) and the low envi- ronmental variances related to the genetic variance components (Table 3). Thus, breeders can efficiently eva- luate the designated traits during the selection process.

Understanding the genetic determination of traits helps the breeder in formulating breeding techniques for combining desirable characters that are dispersed in two or more genotypes into one. Identification of the sources contributing to genetic variation and the type of gene actions involved will assist in the selection of the most ap- propriate breeding strategy.

If we consider one gene with two alleles, B and b, we have one of three possible genotypes in the F2 genera- tion or any other segregating generation: BB, Bb and bb. The phenotypic expression of each genotype is deter- mined as the departure from the mid-point (m) between two homozygous parents (BB and bb). Thus, parameter aB measures the departure of each homozygote from m, and dB measures the departure of the heterozygote from m (Figure 4). The phenotypic expression of BB and bb would be m + aB and m – aB, respectively, and that of Bb would be m + dB. When more than one locus is involved, the expected phenotypic expression of each genotype is determined as the sum of the effects at the individual loci [29] ; therefore this model can be extended to any number of loci. Therefore, a represents the additive effect if dominance is absent (d = 0) or allelic frequency is 0.5 (B = b), that is when we cross two inbred lines [30] . The magnitude of d will change depending upon the de- gree and direction of dominance (add), i.e., the d/a ratio.

The model can also be extended to include non-allelic (epistatic) interaction components [29] . The R2 coeffi-

![]()

Figure 4. Additive (a) and dominant (d) genetic parameter for a given locus-B. Deviations are relative scales to the mid-point (m) between two parents.

cient can be used to choose the most adequate model. Since the estimates of this coefficient were high for all cases (>94%), the epistatic effects should be minimum or null. Thus, adequacy of the simple model, i.e., main effects alone, was satisfactory.

The estimates obtained showed predominance of additive effects, evidenced by add. Nevertheless, d is not negligible. In early literature, the information found is that trait is controlled by one gene with dominance for the allele controlling nicotine conversion [19] -[21] . This is in agreement with the idea of dominance in the traits genetic control; however, more genes of minor effect must be involved in the biosynthetic pathway because of the quantitative distribution observed in segregating generations (Figure 3). These genes may be responsible for encoding precursors of nicotine and nornicotine or for regulating transcripts that somehow affects the route.

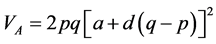

VA and VD estimates were consistent with a and d, as already stated. According to Bernardo [30] , VA does not have a clear meaning, because the term additive does not imply that the alleles have only additive effects. This concept can be better elucidated by its estimator: , in which p and q are the frequen- cies of each allele. The expression indicates that any segregating locus, with or without dominance, can contri- bute to VA. Therefore, the presence of VA does not mean that the allele effects are purely addictive. Therefore, even though low, a degree of dominance was found in the expression of the traits. However, the variance com- ponents generally have high errors associated with the estimates, probably because the data is recorded at the in- dividual level.

, in which p and q are the frequen- cies of each allele. The expression indicates that any segregating locus, with or without dominance, can contri- bute to VA. Therefore, the presence of VA does not mean that the allele effects are purely addictive. Therefore, even though low, a degree of dominance was found in the expression of the traits. However, the variance com- ponents generally have high errors associated with the estimates, probably because the data is recorded at the in- dividual level.

In the literature, estimates of mean and variance components were not found for the traits evaluated in this study. There are reports referring to the number of genes controlling the phenotypic expression. Moreover, in a study performed involving crosses between N. tabacum and related amphidiploids two genes controlling nico- tine conversion were found [32] . In contrast, other studies indicate that one gene is responsible for expression of the trait as already mentioned. Yet for other traits in tobacco, information regarding to genetic components of mean and variance is scarce. Some researchers have performed diallel crosses and evaluated traits associated with tobacco yield [33] -[35] . For all traits evaluated the general combining ability (GCA) was higher than the specific combining ability (SCA), indicating absence of heterosis and, consequently, predominance of additive effects.

For that reason, the selection of plants with low or null nicotine conversion is likely the best strategy for achieving success in breeding programs. Additionally, the narrow sense heritability estimate at the individual level for nicotine conversion was relatively high (76%), which indicates a favorable condition for selection in early generations when practicable. Even so, selection should be associated with a recurrent program because it is not possible to reach the desired nornicotine content after just one selection cycle. One more point to take into considerations is the low correlation estimate (rP) between the total nicotine content before leaf curing and the nornicotine content after curing (−0.09; p-value = 0.22). Hence, selecting for nicotine content does not imply in any consequences for nicotine conversion. In other words, the breeder can select “non-converters” plants with low nicotine content.

In production of foundation seeds, for example, a screening is carried out on all plants to eliminate individuals that exhibit nicotine conversion higher than 3% [36] . In this context, Lewis et al. [37] indicated another evi- dence for quantitative inheritance of nicotine conversion. To quote these authors:

“Although this screening procedure leads to significant reductions in nornicotine (and NNN) in comparison to tobacco populations that have not been screened, this process can never be perfect, since high nornicotine producing converter plants can spontaneously arise with each generation.”

Therefore, genetic control of this trait is not as simple as has been stated by many authors. These unexpected converter plants could be arising from changes in the epigenetic state [38] . In this case, conducting the selection program according to the environmental conditions in which the tobacco plant will be grown in the future is the best option for perpetuating epigenetic effects in the direction desired by breeders.

Since evaluation of nicotine and nornicotine is expensive and laborious, the use of molecular markers linked to one of the major genes controlling the trait could be an alternative for screening the progenies or plants in early generation before being subjected to field evaluation. Markers can be selected in a study like this through the use of a segregating population, but the sequences for primers can also already be found in scientific articles published on the issue [22] . However, it is important to emphasize that there are many other genes of low effect controlling the trait; therefore, selection of progenies and plants in experimental designs is important for making fine adjustments in the inbred lines to be released for commercial purposes.

5. Conclusion

Nicotine conversion had predominantly additive effects. Narrow sense heritabilities at the individual level were higher than 65%. Both of these desirable conditions for conducting a selection program for burley tobacco aim- ing at the development of inbred lines associating yield and other traits with low or null nicotine conversion.

Acknowledgements

This is an academic study supported by Souza Cruz SA. We also thank the Coordenação de AperfeiçoamentoProfissional do Ensino Superior (CAPES) for the Ph.D. scholarship and the Conselho Nacional de Pesquisa e Desenvolvimento (CNPq) for the grant.

NOTES

*Corresponding author.