1. Introduction

We know Fermat’s little theorem and Euler’s φ (phi) function. Such are well defined operations on number theory and algebra. Euler’s φ (phi) function is considered as general proof of Fermat’s little theorem. We seek other ways to find mod values on Fermat’s little theorem, and generalize φ (phi) function for a certain integer’s exponentiation and factorial value. We construct the exponent parallelogram to find the coherence values of Euler’s φ (phi) function. We find higher valued exponents on Fermat’s little theorem according to this. We also specify Fermat’s last theorem by using prime numbers. Also we know binomial coefficients are constructing Pascal’s triangle, in which we see the divisibility of prime numbers (primality test) in prime number exponentiation on Pascal’s triangle. In addition, we construct Pascal’s triangle and seek other ways except for binomial coefficients, i.e. and construct Pascal’s triangle by arithmetic operations triangle. Finally instead of binomial coefficients in Pascal’ triangle, we use exponents value of certain integer to construct Pascal’s triangle, and then use “n”th expansion to find factorial of such certain number.

First Blaise Pascal (1623-1662) introduced Pascal’s triangle, after that, Isaac Newton (1643-1727) used the facts of Pascal’s triangle he developed binomial expansion. He and his followers used binomial theorem for Probability and Statistical problems. Factorial were used to count permutations at as early as the 12th century, by Indian scholars. In 1677, Fabian Stedman described factorial as applied to change ringing, a musical art involving the ringing of many tuned bells. In his words “Now the nature of these methods is such that the change of one number comprehends (includes) changes on lesser numbers”. In that mean period, James Stirling (1692-1770) first introduced one approximation for finding nth factorial of a certain number. Then Adrien-Marrie Legendre used Leonhard Euler’s (1707-1783) second integral formula and notated a symbol for it and then named it as Gamma function. It was a good approximation finding factorial of Real numbers. Jacques Philippe Marie Binet (1786-1856), modified James Stirling’s approximation. Finally, the notation n! was introduced by the French mathematician Christian Kramp in 1808. Pierre de Fermat (1601-1665) stated Little theorem, for any two relatively prime numbers, in which exponent should be prime number; after that Leonhard Euler (1707-1783) found Totient function and then generalized Fermat’s little theorem for any two relatively prime numbers.

From this book “Prime numbers a computational Perspective” [1], we know prime numbers and primality test. From this paper “Fermat’s little theorem” [2], we know various types of explanations about Fermat’s little theorem.

Prepositions 2 to 6 are worked by me. They are noted as PRB which means Prema. R. Balasubramani [3]. They are published in Fermat’s theorem one extension: Mathematical Sciences International Journal ISSN 2278-8697 VOLUME 8 ISSUE 1 (JUNE 2019), P. 6-10.

In this paper,

1) I retreat my previous work Fermat’s theorem one extension. Here I extend my works to finding the coherence numbers (constructing exponent parallelogram) for Euler’s phi function and then generalize it for Fermat’s little theorem.

2) I test the primality of prime numbers on Pascal’s triangle.

3) I specify Fermat’s last theorem by prime numbers.

4) I generate Pascal’s triangle by arithmetic operations.

5) I find factorial value for certain number by using exponent triangle.

2. Discussion and Results

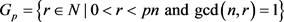

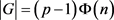

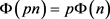

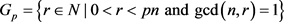

Hint 1: Define . Then

. Then  .

.

Hint 2: Define . Then

. Then  .

.

2.1. Let’s Now Examine φ(pn) When p Is a Factor of n

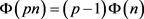

Lemma 1: Let p be a prime and p divides n, then .

.

Proof: Notice that all the numbers that are relatively prime to pn are also relatively prime to n. since  and p divides n the following result follows:

and p divides n the following result follows:  if and only if

if and only if  for any natural number r.

for any natural number r.

There are p intervals, each with Φ(n) numbers relatively prime to pn, hence by the hint 1: the set  has

has  elements. □

elements. □

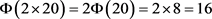

For our example we choose 20, so let’s consider 2 × 20;  . Putting together the two sets mentioned in our previous examples we have {1, 3, 7, 9, 11, 13, 17, 19, 21, 23, 27, 29, 31, 33, 37, 39}, exactly all 16 numbers are relatively prime to 40.

. Putting together the two sets mentioned in our previous examples we have {1, 3, 7, 9, 11, 13, 17, 19, 21, 23, 27, 29, 31, 33, 37, 39}, exactly all 16 numbers are relatively prime to 40.

2.2. Let’s Now Examine φ(pn) When p Is Not a Factor of n

Lemma 2: Let p be a prime and p does not divide n, then  .

.

Proof: We know that pΦ(n) is the number of numbers relatively prime to n and less than pn. Notice that all the multiples of p whose factors are relatively prime to n are counted, since . Notice the conditions imply

. Notice the conditions imply  iff

iff  and

and .

.

Suppose the list of multiples is , where all the r’s are relatively prime to n. the set has Φ(n) numbers relatively prime to n and 0 relatively prime to p, because they are all multiples of p. we subtract this many from our original count and we have

, where all the r’s are relatively prime to n. the set has Φ(n) numbers relatively prime to n and 0 relatively prime to p, because they are all multiples of p. we subtract this many from our original count and we have .□

.□

For our examples we choose 20, so let’s consider 3 × 20;![]() . Putting together the two sets mentioned in our previous examples we have {1, 7, 11, 13, 17, 19, 23, 29, 31, 37, 41, 43, 47, 49, 53, 59} exactly all 16 numbers relatively prime to 60.

. Putting together the two sets mentioned in our previous examples we have {1, 7, 11, 13, 17, 19, 23, 29, 31, 37, 41, 43, 47, 49, 53, 59} exactly all 16 numbers relatively prime to 60.

Preposition 1: Let n be a positive integer. Then ![]() when n is composite number and

when n is composite number and ![]() when n is prime number.

when n is prime number.

Proof: Let n be a positive integer.

When n be a composite number and n divides![]() , then

, then ![]() .

.

Notice that all the numbers that are relatively prime to ![]() are also relatively prime to

are also relatively prime to![]() . Since

. Since ![]() And n divides

And n divides ![]() The following result follows:

The following result follows: ![]() if and only if

if and only if ![]() for any natural number r.

for any natural number r.

There are n intervals, each with ![]() numbers relatively prime to

numbers relatively prime to![]() , hence by the hint 1: the set

, hence by the hint 1: the set ![]() has

has ![]() elements.

elements.

When n be a prime and n does not divide![]() , then

, then ![]() .

.

We know that ![]() is the number of numbers relatively prime to

is the number of numbers relatively prime to ![]() and less than

and less than![]() . Notice that all the multiples of n whose factors are relatively prime to

. Notice that all the multiples of n whose factors are relatively prime to ![]() are counted, since

are counted, since![]() . Notice the conditions imply

. Notice the conditions imply ![]() if and only if

if and only if ![]() and

and![]() .

.

Suppose the list of multiples is![]() , where all the r’s are relatively prime to

, where all the r’s are relatively prime to![]() . The set has

. The set has ![]() numbers relatively prime to

numbers relatively prime to ![]() and 0 relatively prime to n, because they are all multiples of n. by this way we get

and 0 relatively prime to n, because they are all multiples of n. by this way we get![]() .

.

Preposition 2 (PRB): Let n be a positive integer. Then ![]() where ni’s are composite numbers and

where ni’s are composite numbers and![]() ’s are prime numbers not exceeding n.

’s are prime numbers not exceeding n.

Proof:

Using preposition 1, we obtained ![]() when n is composite number and

when n is composite number and

![]() when n is prime number. Since all even numbers are composites except 2 because 2 is prime. So we cannot find an even composite number less than four. And two is the only prime number less than three. Also 1 is the only number relatively prime to two and below it. So we obtained from these two equations we get

when n is prime number. Since all even numbers are composites except 2 because 2 is prime. So we cannot find an even composite number less than four. And two is the only prime number less than three. Also 1 is the only number relatively prime to two and below it. So we obtained from these two equations we get

![]() (1)

(1)

Example 1: Find the value of ![]()

Solution:

Let ![]() then we can write

then we can write![]() . So

. So

![]() .

.

Example 2: Find the value of ![]()

Solution:

Let ![]() then

then![]() . So

. So

![]()

Preposition 3 (PRB): Let n be a positive integer and “a” be an exponent to n. Then![]() .

.

Proof: The positive integers less than na that are not relatively prime to n are those integers not exceeding na that are divisible by n. There are exactly na-1 such integers, so there are ![]() integers less than na that are relatively prime to na.

integers less than na that are relatively prime to na.

Hence,

![]() (2)

(2)

Example 4: Find the value of φ(104).

Solution:

Let φ(104) then![]() .

.

Since 10 is a composite, 104 = 10,000 so φ(10,000) = 4000.

Example 5: Find the value of φ(3315).

Solution:

Let φ(3315) then

![]()

Since 331 is a prime, 3315 = 3,973,195,810,651 so φ(3,973,195,810,651) = 3,961,192,197,930.

2.3. Exponent Division on Fermat’s Little Theorem

Preposition 4 (PRB): If p is prime and “a” is a positive integer with p does not divides “a”, ![]() and n be an exponent to “a” then

and n be an exponent to “a” then![]() . r is a congruent of “a” for mod p, where “s” is a quotient and “t” is a residue when “n” divided by p and

. r is a congruent of “a” for mod p, where “s” is a quotient and “t” is a residue when “n” divided by p and ![]() is any exponent.

is any exponent.

Proof: Let p be a prime, and a is a positive integer with p does not divides a, ![]() and n be an exponent to a then

and n be an exponent to a then

![]() ;

; ![]()

![]() if

if ![]() then

then

![]() if

if ![]() then

then

Do this again and again until we get ![]()

![]() if

if![]() .

.

Hence we get,

![]() (3)

(3)

2.4. Proving Fermat’s Little Theorem, Using Preposition 4

If p is prime and a is a positive integer with p does not divides “a” and ![]() then

then![]() .

.

ð ![]() .

.

Example 6: Find the value of 31900 mod 13.

Solution: We can write

1900 = 146.13 + 2

≡146 + 2 = 148 here 148 ≥ 13 so,

148 = 11.13 + 5

≡16 here 16 ≥ 13 so,

19 = 1.13 + 3

≡4 here 4 < 13 so,

Apply this algorithm, then we get

![]() .

.

Preposition 5 (PRB): If m is a positive integer and a is an integer with (a, m) = 1,

Then![]() .

.

where

![]() (4)

(4)

Proof:

Let![]() . So we can write

. So we can write ![]() for some integer m. now we can write

for some integer m. now we can write![]() . Here

. Here![]() , since k value has φ(m) as a one factor and n is a positive integer.

, since k value has φ(m) as a one factor and n is a positive integer.

It gives

![]() .□

.□

Example 8: Find the value of ![]()

Solution:

![]() .

.

Preposition 6 (PRB): If m is a positive integer and a is an integer with (a, m) = 1,

Then![]() .

.

where

![]() (5)

(5)

Proof: Let ![]() then

then![]() . So we can write

. So we can write ![]() for some integer m. Now

for some integer m. Now![]() . Here

. Here![]() . Since k has φ(m) as a one factor and h is a positive integer. It gives

. Since k has φ(m) as a one factor and h is a positive integer. It gives![]() . □

. □

2.5. Exponent Parallelogram

Definition 1: Let ![]() and

and ![]() be the exponent to m then do 1st operation is subtracting each element with its successive element of 1st line elements. Result will be

be the exponent to m then do 1st operation is subtracting each element with its successive element of 1st line elements. Result will be![]() , we shall name

, we shall name ![]() as “a”. 2nd operation is subtracting each element with its successive element of 1st operation, result will be

as “a”. 2nd operation is subtracting each element with its successive element of 1st operation, result will be ![]() then we shall name

then we shall name ![]() as “a2”. 3rd operation is subtracting each element with its successive element of 2nd operation, result will be

as “a2”. 3rd operation is subtracting each element with its successive element of 2nd operation, result will be ![]() then we shall name

then we shall name ![]() as “a3”. By this way we do the same up to nth operation. These 1st line to nth operation diagonal elements coefficients construct exponent parallelogram.

as “a3”. By this way we do the same up to nth operation. These 1st line to nth operation diagonal elements coefficients construct exponent parallelogram.

Now we construct exponent parallelogram:

![]()

Note: ![]() should be placed between

should be placed between ![]() and

and ![]() in kth operation. Because

in kth operation. Because![]() .

.

Let we construct exponent plane for 5: for ![]() and

and ![]()

![]()

Now we get,

![]()

By the above results we define,

1) If “E” is a 1st line prime exponent and “a” is an integer with (a, E) = 1, then![]() .

.

2) If “E” is a prime exponent and “a” is an integer with (a, E) = 1, then![]() , where “k” is any positive integer of 1st operation to k-th operation coherence numbers of φ(E).

, where “k” is any positive integer of 1st operation to k-th operation coherence numbers of φ(E).

Examples:

1) Let 7 is a first line prime exponents i.e. (1, 7, 49, 343,![]() ) and

) and ![]() with (4, 7) = 1, then

with (4, 7) = 1, then![]() .

.

2) Let 7 is a first line prime exponents, (6, 42, 294, 2058,![]() ) are 1st operation to kth operation and

) are 1st operation to kth operation and ![]() with (4, 7) = 1, then

with (4, 7) = 1, then![]() . Where 6, 42, 294, 2058,

. Where 6, 42, 294, 2058, ![]() are coherence numbers of φ(7).

are coherence numbers of φ(7).

3) Let 5 is a first line prime exponents, (4, 5 × 4, 25 × 4, 125 × 4, ![]() , 16, 5 × 16, 25 × 16,

, 16, 5 × 16, 25 × 16, ![]() , 64, 5 × 64, 25 × 64,

, 64, 5 × 64, 25 × 64,![]() ) are 1st operation to kth operation and

) are 1st operation to kth operation and ![]() with (4, 5) = 1, then

with (4, 5) = 1, then![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

,![]() . Where (4, 5 × 4, 25 × 4, 125 × 4,

. Where (4, 5 × 4, 25 × 4, 125 × 4, ![]() , 16, 5 × 16, 25 × 16,

, 16, 5 × 16, 25 × 16, ![]() , 64, 5 × 64, 25 × 64,

, 64, 5 × 64, 25 × 64,![]() ) are coherence numbers of φ(5) and

) are coherence numbers of φ(5) and![]() .

.

2.6. Prime Bases on Fermat’s Last Theorem

Let we see following summations.

Let ![]() are prime numbers then

are prime numbers then

![]() ;

;

For squared primes:

![]() ;

;

![]() ;

;

![]() ;

;

![]() ;

;

For cubed primes:

![]() ;

;

![]() ;

;

![]() ;

;

![]() ;

;

For fourth exponent primes:

![]() ;

;

![]() ;

;

![]() ;

;

![]() ;

;

By this way we concluded,

![]() .

.

where![]() .

.

From the above recursion, we formulate the result then we get,

![]() .

.

where

![]() (6).

(6).

Theorem 1: Let ![]() are prime numbers then

are prime numbers then![]() . Where q is any prime.

. Where q is any prime.

Proof:

Let ![]() then

then

Case 1: If P is prime, result is obvious.

Case 2: If P is composite, we can write![]() . if

. if ![]() then result is obvious.

then result is obvious.

Case 3: If P is composite and![]() , then we can write

, then we can write![]() . If

. If ![]() are distinct primes then result is obvious. But if

are distinct primes then result is obvious. But if ![]() we get

we get![]() . This result contradict with (1). So

. This result contradict with (1). So![]() . Where q is any prime.

. Where q is any prime.

2.7. Primality of Pascal’s Triangle

Definition 2: For all ![]() and for all reals

and for all reals ![]() we have the formula

we have the formula![]() . For every

. For every ![]() we have

we have ![]() then p divides

then p divides ![]() and every

and every![]() ; where

; where ![]() is called Primality of binomial expansion.

is called Primality of binomial expansion.

Prime number Pascal’s triangle coefficients

0 1

1 1 1

2 1 2 1

3 1 3 3 1

4 1 4 6 4 1

5 1 5 10 10 5 1

6 1 6 15 20 15 6 1

7 1 7 21 35 35 21 7 1

…

11 1 11 55 165 330 462 462 330 … 1

…

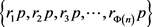

p ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() where

where ![]()

Examples:

1) 7 divides 7 + 21 + 35 + 35 + 21 + 7 i.e. 126/7 = 18

2) 11 divides 2(11 + 55 + 165 + 330 + 462) i.e. 2046/11 = 186.

2.8. Constructing Pascal’s Triangle by Arithmetic Triangles

Addition triangle

Definition 3: Let ![]() then do 1st operation is adding each element with its successive element of 1st line elements, 2nd operation is adding each element with its successive element of 1st operation, and 3rd operation is adding each element with its successive element of 2nd operation. By this way we do the same up to nth operation. These 1st line to nth operation diagonal elements coefficients construct Pascal’s triangle.

then do 1st operation is adding each element with its successive element of 1st line elements, 2nd operation is adding each element with its successive element of 1st operation, and 3rd operation is adding each element with its successive element of 2nd operation. By this way we do the same up to nth operation. These 1st line to nth operation diagonal elements coefficients construct Pascal’s triangle.

Now we construct addition triangle:

1st line: ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

1st operation: ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

2nd operation: ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

3rd operation: ![]()

![]()

![]()

4th operation: ![]()

![]()

5th operation: ![]()

From the above, using the colored diagonal we can construct a Pascal’s triangle:

1

1 1

1 2 1

1 3 3 1

1 4 6 4 1

1 5 10 10 5 1

1 6 15 20 15 6 1

- - - - - - - -

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() - - -

- - - ![]()

![]() .

.

2.9. Backward Difference Triangle

Definition 4: Let ![]() then do 1st operation is subtracting each element with its predecessor element of 1st line elements, 2nd operation is subtracting each element with its predecessor element of 1st operation, and 3rd operation is subtracting each element with its predecessor element of 2nd operation. By this way we do the same up to nth operation. These 1st line to nth operation diagonal elements coefficients construct Pascal’s triangle with negative coefficients.

then do 1st operation is subtracting each element with its predecessor element of 1st line elements, 2nd operation is subtracting each element with its predecessor element of 1st operation, and 3rd operation is subtracting each element with its predecessor element of 2nd operation. By this way we do the same up to nth operation. These 1st line to nth operation diagonal elements coefficients construct Pascal’s triangle with negative coefficients.

Now we construct backward difference triangle:

1st line: ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

1st operation: ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

2nd operation: ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

3rd operation: ![]()

![]()

![]()

4th operation: ![]()

![]()

5th operation: ![]()

From the above, using the colored diagonal we can construct a negative Pascal’s triangle:

1

−1 1

1 −2 1

−1 3 −3 1

1 −4 6 −4 1

−1 5 −10 10 −5 1

1 −6 15 −20 15 −6 1

- - - - - - - -

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() - - -

- - - ![]()

![]() , where

, where ![]() sign depends upon whether n is odd or even. If n is odd we get

sign depends upon whether n is odd or even. If n is odd we get![]() , else we get

, else we get![]() .

.

2.10. Forward Difference Triangle

Definition 5: Let ![]() then do 1st operation is subtracting each element with its successive element of 1st line elements, 2nd operation is subtracting each element with its successive element of 1st operation, and 3rd operation is subtracting each element with its successive element of 2nd operation. By this way we do the same up to nth operation. These 1st line to nth operation diagonal elements coefficients construct Pascal’s triangle with negative coefficients.

then do 1st operation is subtracting each element with its successive element of 1st line elements, 2nd operation is subtracting each element with its successive element of 1st operation, and 3rd operation is subtracting each element with its successive element of 2nd operation. By this way we do the same up to nth operation. These 1st line to nth operation diagonal elements coefficients construct Pascal’s triangle with negative coefficients.

Now we construct forward difference triangle:

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

From the above, using the colored diagonal we can construct a negative Pascal’s triangle:

1

1 −1

1 −2 1

1 −3 3 −1

1 −4 6 −4 1

1 −5 10 −10 5 −1

1 −6 15 −20 15 −6 1

- - - - - - - -

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() - - -

- - - ![]()

![]() where

where ![]() sign depends upon whether n is odd or even. If n is odd we get

sign depends upon whether n is odd or even. If n is odd we get![]() , else we get

, else we get![]() .

.

2.11. Multiplication Triangle

Definition 6: Let ![]() then do 1st operation is multiplying each element with its successive element of 1st line elements, 2nd operation is multiplying each element with its successive element of 1st operation, and 3rd operation is multiplying each element with its successive element of 2nd operation. By this way we do the same up to nth operation. These 1st line to nth operation diagonal elements degrees construct Pascal’s triangle.

then do 1st operation is multiplying each element with its successive element of 1st line elements, 2nd operation is multiplying each element with its successive element of 1st operation, and 3rd operation is multiplying each element with its successive element of 2nd operation. By this way we do the same up to nth operation. These 1st line to nth operation diagonal elements degrees construct Pascal’s triangle.

Now we construct multiplication triangle:

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

From the above, using the colored diagonal exponents, we can construct a Pascal’s triangle:

1

1 1

1 2 1

1 3 3 1

1 4 6 4 1

1 5 10 10 5 1

1 6 15 20 15 6 1

- - - - - - - -

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() - - -

- - - ![]()

![]()

2.12. Forward Division Triangle

Definition 7: Let ![]() then do 1st operation is dividing each element with its successive element of 1st line elements, 2nd operation is dividing each element with its successive element of 1st operation, and 3rd operation is dividing each element with its successive element of 2nd operation. By this way we do the same up to nth operation. These 1st line to nth operation diagonal elements degrees construct Pascal’s triangle.

then do 1st operation is dividing each element with its successive element of 1st line elements, 2nd operation is dividing each element with its successive element of 1st operation, and 3rd operation is dividing each element with its successive element of 2nd operation. By this way we do the same up to nth operation. These 1st line to nth operation diagonal elements degrees construct Pascal’s triangle.

Now we construct forward division triangle:

![]()

From the above, using the colored diagonal exponents, we can construct a Pascal’s triangle:

1

1 −1

1 −2 1

1 −3 3 −1

1 −4 6 −4 1

1 −5 10 −10 5 −1

1 −6 15 −20 15 −6 1

- - - - - - - -

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() - - -

- - - ![]()

![]() , where

, where ![]() sign depends upon whether n is odd or even. If n is odd we get

sign depends upon whether n is odd or even. If n is odd we get![]() , else we get

, else we get![]() .

.

Upon whether n is odd or even. If n is odd we get![]() , else we get

, else we get![]() .

.

2.13. Backward Division Triangle

Definition 8: Let ![]() then do 1st operation is dividing each element with its successive element of 1st line elements, 2nd operation is dividing each element with its successive element of 1st operation, and 3rd operation is dividing each element with its successive element of 2nd operation. By this way we do the same up to nth operation. These 1st line to nth operation diagonal elements degrees construct Pascal’s triangle.

then do 1st operation is dividing each element with its successive element of 1st line elements, 2nd operation is dividing each element with its successive element of 1st operation, and 3rd operation is dividing each element with its successive element of 2nd operation. By this way we do the same up to nth operation. These 1st line to nth operation diagonal elements degrees construct Pascal’s triangle.

Now we construct backward division triangle:

![]()

From the above, using the colored diagonal exponents, we can construct a Pascal’s triangle:

1

−1 1

−1 2 −1

−1 3 −3 1

−1 4 −6 4 −1

−1 5 −10 10 −5 1

−1 6 −15 20 −15 6 −1

- - - - - - - -

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() - - -

- - - ![]()

![]() , where

, where ![]() sign depends

sign depends

2.14. Backward Exponent Difference Triangle

Definition 9: Let ![]() then do 1st operation is multiplying each element with its successive element of 1st line elements, 2nd operation is multiplying each element with its successive element of 1st operation, and 3rd operation is multiplying each element with its successive element of 2nd operation. By this way we do the same up to nth operation. These 1st line to nth operation diagonal elements degrees construct Pascal’s triangle.

then do 1st operation is multiplying each element with its successive element of 1st line elements, 2nd operation is multiplying each element with its successive element of 1st operation, and 3rd operation is multiplying each element with its successive element of 2nd operation. By this way we do the same up to nth operation. These 1st line to nth operation diagonal elements degrees construct Pascal’s triangle.

Theorem 2: Let ![]() be an exponent of any

be an exponent of any ![]() then “n”th difference of

then “n”th difference of ![]() would be n!.

would be n!.

Let we construct backward difference triangle, in which first line numbers are “n”th exponent of whole numbers. For any![]() ,

,

1st line: ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

1st operation: ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

2nd operation: ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

3rd operation: ![]()

![]()

![]()

…

nth operation:![]() . □

. □

2.15. Forward Exponent Difference Triangle

Definition 10: Let ![]() then do 1st operation is subtracting each element with its successive element of 1st line elements, 2nd operation is subtracting each element with its successive element of 1st operation, and 3rd operation is subtracting each element with its successive element of 2nd operation. By this way we do the same up to nth operation. These 1st line to nth operation diagonal elements degrees construct Pascal’s triangle.

then do 1st operation is subtracting each element with its successive element of 1st line elements, 2nd operation is subtracting each element with its successive element of 1st operation, and 3rd operation is subtracting each element with its successive element of 2nd operation. By this way we do the same up to nth operation. These 1st line to nth operation diagonal elements degrees construct Pascal’s triangle.

Theorem 3: Let ![]() be an exponent of any

be an exponent of any ![]() then “n”th difference of

then “n”th difference of ![]() would be

would be![]() .

.

Proof:

Let we construct forward difference triangle, in which first line numbers are “n”th exponent of whole numbers. For any![]() ,

,

1st line: ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

1st operation: ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

2nd operation: ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

3rd operation: ![]()

![]()

![]()

…

nth operation:![]() . ■

. ■

Examples for backward exponent difference method:

1) Let m = 0 and n = 5 then

![]()

2) Let m = −1 and n = 5 then

![]()

3) Let m = 1 and n = 5 then

![]()

Examples for backward exponent difference method:

1) Let m = 0 and n = 4 then

![]()

2) Let m = −1 and n = 4 then

![]()

3) Let m = 1 and n = 5 then

![]()