Creative Education 2013. Vol.4, No.6, 376-387 Published Online June 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ce) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ce.2013.46054 Copyright © 2013 SciR e s . 376 Using Figurative Language to Assess the Stage of Acceptance of Learning Disability as a Springboard for Treatment of Students with Learning Disabilities Sara Givon Education Department, Lifshitz College for Teachers, Jerusalem, Israel Email: givonsara@gmail.com Received March 25th, 2013; revised April 27th, 2013; accepted May 7th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Sara Givon. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribu- tion License, which permits unrestricted use, dist ribution, and r eproduction in any medium, provided the o riginal work is properly cited. In order to examine the emotional and cognitive processes experienced by adolescents with learning dis- abilities (LD), twenty tenth grade Israeli students were studied over three years. Data gathered through in-depth interviews underwent an axial-coding process, and a grounded theory model was constructed. The findings revealed various coping styles adopted by students throughout the process of accepting the disability. Participants were asked to use figurative language to describe their method of coping with the disability. Participants’ choice of phrase, metaphor or image characterized the phase of their acceptance as well as their coping style. This can be served as an effective tool of detection. Identifying the stage of students’ acceptance and their coping style may promote optimal treatment for students with LD. Keywords: Figurative Language; Adolescents with Learning Disabilities; Coping Styles; Grounded Theory Introduction Growing awareness among parents and teachers of the need of students with learning disabilities to acquire education as a basic requirement towards obtaining a profession and integrat- ing into society, led to increased commitment to diagnosis of LD and hence an increase in dispensations and accommoda- tions granted to students with LD (Margaolit, Efrati, & Da- nino, 2002). In addition to accommodations, allocation of re- sources and educational restructuring are also required, based on understanding the factors that help or hinder the success of these students in matriculation examinations (Ellis & Larkin, 1998; Ellis & Siegler, 1997; Larkin, 2009). The purpose of this study was to add to theoretical and practical knowledge of cognitive and emotional intra-personal and inter-personal pro- cesses. The study identified the factors involved in both the emotional and cognitive stages of accepting (and thus coping with) learning disabilities, distinguishing between various types of disabilities. Based on grounded theory, a model was cons- tructed for the purpose of enabling counselors, teachers and caregivers to match the type of intervention to the specific needs of each group in order to improve the effectiveness of in- tervention programs. Students’ figurative language was shown to assist in identify- ing the stage where they are at in the process of accepting the disability. The figurative speech, phrase or image that students choose for describing their acceptance of their learning disabi- lity, reveals both the phase in the process and the style of their coping with the disability. Detection of the stage and the coping style may help counselors to create an intervention program tailored to the precise needs of individual adolescents. Learning Disabilities: Definition and Characterization The definition1 of the National Joint Committee on Learning Disabilities (NJCLD) is generally accepted by the US Ministry of Education. This definition refers to a possible source of disabilities- central neurological dysfunction, i.e. primary disability that aff- ects the learning ability and the connection between the indi- vidual and his or her environment. Even in Israel it is now customary to use this definition in order to characterize and diagnose students with learning disabilities (Israeli Ministry of Education, 2003) though this definition is somewhat contro- versial and has undergone new formulations even in the United States. The Relationship between Cognitive and Emotional Characteristics Until now, most studies of LDs have focused on the qua- litative and quantitative aspects of the limitations of students with learning disabilities and with understanding the reasons 1“Learning disability isa general term referring to a heterogeneous group o disorders as expressed in significant difficulties acquiring listening, speaking, reading, writing, conceptualizing and/or mathematical abilities and the use thereof. These disorders are intrinsic to the individual, and assumed to stem from a central n eurological dysfunct ion. They may appear at any point along the life cycle. Although the learning disability can occu at the same time with other restrictive conditions (sensory damage, mental retardation,emotional and social disorder) or external conditions (cultural differences, inadequate or unfit instruction), the learning disabilities a not a direct result of these conditions” (NJCLD, 1994).  S. GIVON for their difficulties in functioning. However, clinical ex- perience has indicated that it is difficult to predict the chances of adjustment in children with learning disabilities, if the only aspect related to is their disability level and cognitive disability (Frith, 1999). In the adolescence years, increased demands from the environment, along with the need for independence and building new friendships, raise in adolescents tensions and feelings of commitment, ambivalence towards school and fam- ily, plus the desire to belong to their peer group. Studies show that sub-specific types of students with learning disabilities, with clear patterns of capabilities and neuro-cognitive short- comings, show different patterns of psychosocial functioning. These patterns are evident especially among students with non- verbal learning disabilities (NLD) who are more likely to deve- lop emotional problems during adolescence into adulthood (Court & Givon, 2003; Greenham, 1999; Little, 1999; Rour- ke,1995). It was also found that the difficulties of students with NLD increase with age and lead to reduced self-esteem in adulthood, placing these students at increased risk of introvert reactions of loneliness, depression, feelings of victimization and chronic feelings of shame (Little, 1999; Palombo, 2001; Petti et al., 2003; Pelletier, 2001). Emotional Distress and Depression The Children with learning disabilities reported more intense feelings of depression than children without learning disa- bilities; they also reported negative moods and a sense of sad- ness and loneliness (Bloom & Heath, 2010; Lackaye & Mar- galit, 2006; Margalit, Efrati & Danino, 2002). The prevalence of depression symptoms is higher among adolescents than among younger children and also higher among girls than boys (Huntington & Bender, 1993). This is due to the fact that adole- scence itself is characterized by sharp fluctuations in mood, hormonal changes, search for identity and a desire to achieve high social status. Symptoms of depression are more common in students with NLD than in those with verbal LD (Dorfman, 2001; Petti et al., 2003). Lackaye et al. (Lachaye, Margalit, Ziv & Ziman, 2006) found that even when students with learning disabilities get higher marks than their friends because of the extra help they receive, their social profile is still lower; they are depressed, lack hope for the future, are lonelier and have darker moods than their friends. Thus they are less acade- mically effective because they lack motivation. Self-Perception and Copying with Learning Challenges For a long time researchers thought that students with learn- ing disabilities would have lower self-esteem than their peers. This assumption was based on the belief that the continued academic failure of these students would undermine their self- esteem (Chapman, 1988; Rogers & Saklofski, 1985). However, a study which used multi-dimensional tools for the estimation of self-perception and self-esteem, revealed that self-image is composed of different sub-perceptions in different areas that separate gradually over the period of formation of the self- image (Dyson, 1996, 2010). Therefore, students with learning disabilities who allocate a special place for their disability are able to formulate a positive self-concept despite the disability. The perception of disability (recognizing its existence and reducing its importance), is another meaningful element in the overall self-concept of students with learning disabilities (Ger- ber, Ginsberg, & Gerber, 1994; Madaus, Gerber, & Price, 2008; Mather & Gregg, 2006). A perception that refers to the limited issue instead of a global perception can help foster self-esteem in children with learning disabilities (Rothman & Cosden, 1995). The above research noted that self-image served as an index to predict academic achievement, while the emotional block, resulting from lack of awareness and non-acceptance of the disability, prevents the formation of effective ways of cop- ing. Academic Copying of Adolescents with Learning Disabilities In interaction with the environment, the individual is subject to external and internal requirements which oblige him or her to recruit cognitive and emotional efforts. When these require- ments exceed the resources at his or her disposal, it is said that the individual is required to “cope” (Bailey, Barton, & Vignola, 1999). Gramzey and Masten (1991) define “durability” as the individual's ability to successfully reach the stage of adaptation, despite challenging or threatening circumstances. Many studies have shown that an internal focus of control and higher self- esteem are associated with better ability to withstand stress- related learning tasks, higher persistence and greater willing- ness to accept assistance and guidance in school (Abouserie, 1994; Maqsud, 1993; Mooney, Sherman, & LoPresto, 1991; Sterbin & Rakow, 1996). Therefore, the more the student deve- lops the sense of comprehensibility, control and meaning, the more he or she will be able to persist in efforts to succeed. But how can the student do so when the resources at his or her disposal are few? The adaptive child, who is also the effective learner, is an active learner, while the behavior strategies of children with learning disabilities are characterized by passive learning; they hold beliefs that attribute their difficulties to uncontrollable factors and they develop acquired helplessness. Both erroneous beliefs and passive attitudes affect the student’s ability to learn and contribute to the creation of academic problems, low self-efficacy, hopelessness and lack of motiva- tion (Margalit, 1996). Ways of Bypassing or Wa ys of Copying The education system recognizes the special needs of students with learning disabilities and invests efforts and re- sources in the advancement of these students. The main ques- tion in this regard is, whether it is more worthwhile to take care of the disability itself or to teach the student ways around it. For many years the prevailing view was that learning disabilities tend to disappear by themselves. Today it is understood that learning disabilities do not disappear with age; they are caused by cognitive-neurological deficiencies, and except for slight and gradual improvement which is a natural part of growing up, the disability accompanies the person throughout his or her life (Gerber et al., 1992; Gerber, 1994; Gregg, 2007; Gregg, Hoy, & Gay, 1996; Madaus, Gerber, & Price, 2008; Mather & Gregg, 2006; Taymans, Swanson, Schwatrz, Gregg, Hock, & Gerber, 2009). Therefore, students with learning disabilities should re- ceive learning accommodations. In order to reach the optimal degree of utilization of those accommodations, caregivers should listen to the students and learn their wishes and opinions as to the various types of accommodation methods that are offered, with reference to the effectiveness of each. This listen- ing should be done with sensitivity, in an attempt to understand Copyright © 2013 SciRe s . 377  S. GIVON the differences that may exist between students with different types of learning disabilities (Margalit, Efrati, & Danino, 2002). Figurative Language as a Tool for Diagnosis and Treatment Figurative language includes words and phrases that function in a symbolic or indirect manner, as they are taken from a cert- ain field and transferred to another one, carrying their original meaning along with them. Figurative language consists of phra- ses with an unclear semantic status that illustrates the abstract. The main kinds of figurative speech are simile, metaphor, personification, metonymy (“I am not Rothschild”), imagery and irony. Symbols serve an important role in understanding the human soul, since they represent an essence which is be- yond their literal meaning (Young, 1964). Metaphor, as well as metonymy and image, is a kind of linguistic expression which can be used to convey an idea using a phrase from another discipline, sometimes completely different, in order to add “borrowed” meaning, and better explain the intent of the origi- nal idea, add another layer of meaning, or “load” additional meaning that was absent before. The use of figurative language may assist in treatment, since sometimes the student and the educational professional face a dead-end when searching for a fitting word or definition and only disengagement from the limitations of language helps in overcoming and relocating from the verbal channel to the visual, sensory or emotional alternatives. Using figurative language is a very common practice in the clinical disciplines for the pur- pose of treatment, but also for diagnosis, since figurative lan- guage and images do not bear within them any threat. The user can stay remote to some extent, and this fact is helpful in identifying hidden messages (Elitzur, 1986). In a semi-struct- ured in-depth interview, the access to the patient is direct, which makes it difficult to discover hidden feelings as may be expressed by the subjects without self-censorship (Sobel, 2006). In understanding young people with learning disabilities, meta- phor may help clarify the relationship between unexpressed feelings and emotions and the manifest declarations that stud- ents use to define their disability and describe the hardships of studying. Learning disabilities are often related to central cognitive impairment or deficiency, and may involve the speech center in the brain (verbal learning disability). Even in the case of non- verbal learning disabilities, there are indirect effects on verbali- zation. Metaphorical expression or figurative language is some- times a solution if a particular idea or explanation that one wishes to express is too difficult or abstract and a metaphorical phrase adds the desired meaning. It is extremely important to hear the views of young people with learning disabilities who have difficulties in expressing themselves and to encourage them to find the right way around words in order to express their thoughts and feelings, to enable them to receive meaningful assistance. Figurative linguistic “detours” can help even when the disability is associated with a deficiency in verbal expression. The ability to think on “bo- rrowed” meanings and to find alternative images or express- ions in order to convey their intentions may help youth with learning disabilities to express ideas which they find difficult to express. There are cases, especially when the disability is a result of multi-system impairment, that metaphors and figura- tive language are the only way to communicate and convey ideas (Olsen, 2010). Research Questions The current study was guided by the following questions: 1) What are the emotional processes that students with diff- erent learning disabilities undergo during their studying for a high school diploma? 2) How do students with learning disabilities perceive their coping with the academic goal of achieving a high school diplo- ma, and what are the perceptions of students regarding the difficulties they will face in the future? 3) How does figurative language reveal student’ stage of ac- ceptance of their disability and their method of coping? Research Method This study was based on the testimonies of Israeli high school students with diverse learning disabilities, with empha- sis on students with non-verbal disabilities. The study was con- ducted over three years (grades 10 - 12). In-depth, semi- structured interviews were conducted during each year of the study. In the eleventh grade interview, the participants were asked to describe their coping with disability by using figu- rative language. In the final interview participants were asked to describe the process they went through by using an image or a “linguistic drawing” and also to give a title to their life story. This was not an intervention; it was a research study. But it became clear that the conversations that the researchers had with the students gave the students access to their inner world in new ways and deepened their understanding of what they were going through. Once this became clear, we added an end-of-examinations interview with an additional student, Ofer, who was interviewed only after the matriculation exams. Ofer acted as a kind of “control group” since he did not experience the “intervention” of the interviews. The theoretical paradigm chosen was a qualitative, grounded theory approach. After locating the core categories, new infor- mation was re-assembled, while systematically referring cate- gories to each other, and the data was axially coded as shown in Figure 1. In addition, a link to previous theories was made and finally a grounded theory was constructed, the center of the model being the central phenomenon under investigation—the central category around which the theoretical model was de- veloped (Gibton, 2001; Strauss, 1987). This method is des- cribed thoroughly in a previous article (author reference, 2008). Study Par tic ip ants Out of all the students in ninth grade in a six-year compre- hensive school in central Israel, 20 students with learning disa- bilities were selected as a directed sample. The sample consist- ed of ten girls and ten boys with various learning disabilities, verbal (VLD), non-verbal (NLD) and with Attention deficit- hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Data Collection Semi-structured in-depth interview was a tool to get ac- quainted with the experiences of the adolescents and listen to their voices. The interviews were conducted at three time points related to dealing with matriculation exams: 10th grade, 11th grade and 12th grade. Copyright © 2013 SciR e s . 378  S. GIVON Copyright © 2013 SciRe s . 379 Figure 1. Model of the axial coding that describes the causal conditions and context around the core category led to select the style of coping , and the coping results. Research Procedure In ninth grade, the 20 students with learning disabilities who were selected underwent psychological and didactic diagnoses. In tenth grade, the students were interviewed before the first matriculation exams. In eleventh grade, the students were interviewed for the second time before the matriculation exams of that year. During that interview they were asked to supply a metaphor describing their coping with disability. After completing the matriculation exams and at the end of the twelfth grade, students were inter- viewed for the third time. During the last interview participants were asked to describe the process of coping during the school years by using a metaphor and to give a title to their life story. Findings Data collected in the interviews helped in establishing thema- tic connections, while examination of the nature of relation- ships between the categories helped to re-formulate the know- ledge and organize it in a model of axial coding around a core category that includes two key ideas: In the field of learning—learning difficulties and repetitive failures caused a feeling of helplessness and lack of control. In the emotional field—fear of being labeled as incapable; a sense of threat to the self. The model shows the causative conditions and the internal context that contributed to the ways students coped with accep- tance of their disability—and the outcome—the results of this coping. The process of accepting the disability. We found three stages in the process of acceptance of dis- ability, starting at the discovery stage and ending at the stage of reconciliation: 1) Understanding the meaning of the diagnosis, its objective and importance; understanding the nature of the disability and its significance. 2) Readiness to recruit inner resources in order to invest efforts, and to accept and use accommodations the educational system provides to assist in learning. 3) Readiness to use the recommendations in full, and insis- tence on the right to receive accommodations even if this invol- ves a struggle, exposure or labeling. Identification of the phase at which the student currently is, provides a starting point for the beginning of treatment. For this reason it is highly recommended that school counselors become acquainted with the model as shown in Figure 1. Our data indicate that all students undergo a similar process, from the day they receive the significant diagnosis, to the day when they understand the meaning of the diagnosis and its importance, are willing to reconcile with and accept it, and it becomes part of their self-perception, as expressed by Ofra: [...] From the moment of diagnosis, all the time it is a  S. GIVON matterof process. At least for me it was an endless process in order to accept... You accept yourself every time anew, every time you step through another phase [...] (Ofra ). As the process continues over a longer period, from middle school to the beginning of high school, students go through the various stages gradually, until they are willing to accept the disability and reach a kind of reconciliation before the matri- culation exams. With acceptance they are freed to invest the bulk of their struggle in dealing with challenges of learning and with the cognitive difficulty accompanying the matriculation exams. When the process is prolonged or gets “stuck” in the initial stage of denial, the students find it difficult to make their energies available for cognitive tasks and they engage in deal- ing with the emotions that accompany the problem, as Ofra explained; It is very difficult because beyond the fact that you need to get used to being read aloud to, and all the technical things, for me the mental process was a very significant thing, a very inhibiting thing, when I came to the exam with depression and a specific mental block [...]. (Ofra) Although the learning disability shows its first signs long before the diagnosis, when the adolescent faces the diagnostic results this has an immediate effect and serves as an objective point of reference. He or she gets the results objectively, from an outside person, and the immediate result is a sense of loss- loss of the fact that “I am like all the others.” This important stage of discovery and coping with the loss is a necessary condition to moving on to the stages that follow, until one reaches the stage of reconciliation and adaptation. It seems that the standard model of coping with a loss is compatible with the process of acceptance of the disability. One can look at the moment of diagnosis as the moment from which the process of coping with the loss begins. Characteristics of personality include self-perception and the internal resources with which the adolescent copes with the challenges she/he faces, particularly the matriculation exams. These characteristics are influential in how the adolescent accepts the disability, and the path of progress along the se- quence the stages of accepting the disability as part of each student’s self-identity. One girl said: “Once I accepted it, the society accepted it better as well.” She explained that this did not come easily. She called it “an endless process” with “steps that went up and down”, and said that a cynical remark could throw her back to the starting point of the process. Copying Styles How the adolescent first conceives the situation—as a threat or a challenge—is the main factor in his or her selection of the response to the stressful situation (Ellis & Larkin, 1998). Reactions may focus on the problem itself, in an attempt to channel resources into solving the problem that created the stressful situation, or they may focus on emotions to ease the tension. Our findings reveal two frequently mentioned categories, fear of being labeled and helplessness in learning, leading to developing two parallel core strategies for coping. One is di- rected toward dealing with the emotions that accompany the difficulty, making the adolescent able to avoid being flooded with emotions of threat to self and fear of being labeled as incompetent. The other is aimed at coping with the learning- cognitive difficulty—in order to overcome the helplessness, powerlessness and lack of control over learning. The study found four patterns of coping (these results are related fully in author reference, 2008). These patterns can characterize a stage in the process, can be situation-dependent or can even be asso- ciated with primary features related to the disability, or other characteristics of the adolescent’s personality. Abstaining—or avoidance—a defensive pattern that includes lack of faith in help, unwillingness to cooperate, suppression of the situation, recessive behavior, tendency to withdrawal, seclu- sion or excessive dependency on an adult. Rebellion—a negative and denying pattern, resisting help, with a tendency to blame others for their situation, rebellious behavior, lack of acceptance of their situation, bargaining with the surroundings. Reconciliation—partial reconciliation with the disability. Having not yet reached full adaptation, they sigh and cope, feel limited in some sense, but are willing to cope and invest resour- ces. Determination—reconciliation and acceptance of the disa- bility as part of the self-image. Behavior reflected in the per- ception of the situation as a challenge and desire to prove abi- lity despite the disability. In addition to these four patterns of coping, three adaptive strategies for coping with the sense of threat to self were iden- tified. These were perception of the disability and its contain- ment as part of self-identity, reconstruction of the difficulty and translation of the threat into something less threatening, and changing the attitudes of others, a response that creates a change in the position of the others. In-depth study of various patterns of coping among sub- groups of students with learning disabilities sharpens the differences between the coping styles of students with verbal and nonverbal learning disabilities (Little, 1999). The descrip- tion by our participants of their coping patterns indicates that students with verbal learning disabilities ultimately reach a state of behavior that is more adaptive, reconciled or even deter- mined. In contrast, students with non-verbal learning disa- bilities tend to demonstrate coping styles that are abstaining or rebellious, and sometimes unrealistically determined, a poor match for their situation. This is a result of an unrealistic self- perception of their situation both because of denial and because of personality characteristics rooted in the disability. This is why some participants said that they were not going to report their learning disability at university; they were planning to start a new page. There is great importance to the way the disability is defined on the day of the diagnosis and the feedback conversation that follows. If the definition and conversation are done correctly, they have the power to positively motivate the process of ac- ceptance of the disability. Intervention in the process to enable the student’s advancement should be done by identifying the stage where he or she is, the emotional or cognitive coping style that he or she chooses and the factors that influence this choice. Creating a personalized program tailored to the student on both the emotional and cognitive levels helps him or her reach the stage of adaptive behavior. This study shows that most students have the ability to make appropriate choices for the future when selecting further educa- tional paths, realistically distinguishing between the desired and the possible options and the unattainable and unrealistic ones, while demonstrating academic initiative and efficacy. One par- ticipant spoke of his desire to become a doctor, and said that if Copyright © 2013 SciR e s . 380  S. GIVON he cannot study in Israel because of his low grade-point average, he would go to study in another country but won’t give up, a behavior that tends to indicate a determined style. The choice, at the end of which stands the desire to advance and develop, reinforces the impression that the prolonged experience of difficulties and the continuous struggle that most participants undergo, can be turned into both a spurring and an immunizing factor, unifying all the personality elements toward being capa- ble and withstanding difficulties in future studies. This is evident from their answers to the question whether they will use the academic accommodations in the future. As Ofra answered: “No doubt. I know that otherwise I cannot succeed at the university; it will affect me very much. This is something I need, without someone reading the questionnaire aloud to me—I’m lost.” Using Figurative Language to Identify Students’ Stage of Acceptance of Their Learning Disability In order to detect the inner feelings of the participants, they were asked to use figurative language to describe the difficulty. The goal was to explore the relationship between emotions that were not expressed and the open declarations that were part of their definition of the disability and description of their diffi- culties in school. The question was asked of participants in eleventh grade and again in twelfth grade. In the second inter- view in eleventh grade, when they were well into the process of acceptance of the disability, students were asked to find an image that defined their difficulty by completing the sentence: “For me, studying for tests with a learning disability is like …” The second time, at the end of senior year, after concluding the matriculation exams, the question was asked in the past tense: “For me, coping with the matriculation exams was like …” In the eleventh grade interview not all participants responded in imagery, some due to their cognitive difficulty in creating a figurative image of an emotional, abstract situation. These stu- dents they gave concrete answers, descriptions of the difficulty itself. Others found it difficult to give an image due to their ongoing denial of their situation, and claimed that they had no difficulty at all. But most students presented graphic and co- lorful images taken from their inner world, opening a window into their hidden feelings through a mechanism that allowed them to be less controlled by rational criticism and self- censorship. In eleventh grade seven students said they did not know how to give an image. Some of them claimed to have no learning difficulty. Batya said: “No. I do not have any difficulty, it does not bother me.” Na’ama said: “I do not know. Studying is not hard for me, but doing tests is hard for me.” Adam said: “It (the difficulty) is not as high as the clouds, it’s not that hard.” And Sara said: “It’s just pressure, pressure caused by the need to complete all th e material.” Describing their experience in concrete terms, some partici- pants saw dealing with the difficulty as part of coping with difficulties in life. Eli said: “This is another stage in life—it will pass.” Michael said: “This is one more difficulty in life one must pass.” Zohar explained: “It’s like dealing with life itself, when you learn from your experience and improve.” Nir said: “It’s all the time persevering with the difficulty, but it’s only a difficulty related to school.” Tali did use an image when she defined disability as a feature: “It’s a weak side to deal with”, adding “It’s like wanting to lose weight.” It should be noted that Tali’s use of the image of losing weight may be revealing of an emotional problem related to weight. Due to drastic reduction of her weight she had to work hard to gain weight back, in order to return to normal weight. Nine of the twenty participants did express themselves in images, some of which were focused on the difficulty and some on the process. Those images focused on the difficulty concen- trated on the disability, the restriction and being exceptional. Ofra said: “It’s like hanging out with another five gallons on your back, for nothing.” Later in the interview she described her difficulty in day to day coping: “I feel like a person with one hand tied behind her back.” Chaim said this, too: “It’s as if my hands are tied” and added, “Yes, when someone is a special person he is so special because of a unique feature, perhaps he is wise in a way, perhaps he is very strong, any kind of special advantage [...] it’s just that his hands are tied because of the framework, because of the technical conditions, because of the framework, just a person with tied hands”. Michal emphasized the emotional aspect: “It’s like a man with a hole in his heart.” Aviya defined learning as “an endless war.” Martin said: “It’s like running 2000 meters without stopping, it’s tough.” Two girls described the pressure as a state before explosion. Odeya said, “It’s like a box inside the brain that’s going to explode soon.” Zohar also described it in this way: “It’s a pressure cooker about to explode.” Meira described the process as “extremely difficult, like building a house, something like that.” To the question of how she would build the house, she replied: “Gradually, step by step, that’s the way it, like, has to be done, really consistently.” At the end of the matriculation exams, in the final interview, all twenty students took up the challenge of describing in images the difficulties they faced. It may be that they were more mature at this time and felt it was easier for them to look back and “draw” their coping retrospectively. The descriptions and images given by students in the twelfth grade can be characterized by the fact that these images revealed the whole process they had undergone as well as their current situation. Some focused on the difficulty, some focused on success and some on the process or the transition from difficulty to success. Although there were differences between the students regarding their ability to “draw” images or even to give a concrete “flat” description, they all admitted that they had difficulties. Aviad, Uri and Zohar said it was like overcoming any dif- ficulty, and stressed the overcoming. Sarah and Michal said it was “like coping with something very big, difficult and impor- tant that is very crit i c al in your life.” Six students, when describing the process, focused on the difficulty, but found it difficult to give a figurative description and only said that it was like “a thing that had to be done”. David said: “It was like a difficult thing that needed to be done and there was no choice”. Na’ama said: “It was hard, like dealing with a tough characteristic.” Michael said: “It was like a difficult and annoying thing bothering you all the time.” Adam said it was like “the feeling of showing everyone that I can, like when you want to scream in order to silence everyone.” Odeya said: “Like recruiting forces when there is a desire to reach a certain destination.” Tali, when describing the entire process said: “[It was] like everything that is at first difficult and then easy.” She gave an example: “Like a puzzle with many parts [...] It’s difficult at first, then everything works out and it’s easy” Figurative descriptions that describe the process were given by seven participants. Ofra said: “Like the Copyright © 2013 SciRe s . 381  S. GIVON exodus from Egypt.” Eli: “Like climbing up the stairs.” Aviya: “Like learning to drive a car.” Meira : “Like a long run and then you finally reach the finish line,” moving her shoulders forward in a motion as if she were touching the finish line (Meira is an acclaimed runner and athlete). Nir at first described the diffi- culty of the process as like a man recently weaned from smok- ing being shown a cigarette, but then corrected himself and said: “There is nothing that can compare to it (the difficulty) [...] It was very difficult [...]”. Then he added, “Perhaps like a horse and rider, the horse always feels it is being spurred and wants the rider to get off his back and yet keeps going on and on, something like this. Although you accept the contradictions and all the difficulty you continue, like, to try things” (It is import- ant to note that he imagines himself as the horse, not the rider). He saw his story as a story of overcoming despite enormous difficulty that nothing else can be compared to. Batya, who in twelfth grade agreed to take the exams orally, and managed to succeed, said that the exams were “like a corrective experien- ce.” Danny said it reminded him of “the Bar Mitzvah fears, when you are called to the Torah and have to read in front of everyone and it's difficult [...] but as the Torah portion went on and on it became easier and I was encouraged. It’s just like that in the matriculation exams; at first I had difficulties and then as it progressed I felt it became easier.” Ofer described the coping process as being “like climbing up a mountain [...] to reach its summit at the end, a spot from where you see everything well, you have all of it behind you, you can see that you went through it all”. To the question how he felt after it all, he responded: “I feel good, I feel that I arrived at the mountain okay, not completely exhausted, no, and that way I knew where to exhaust myself hard and where not to. (Ofer) These descriptions show that students, even if at first they denied the difficulty and claimed that it did not exist, admitted at the end of the examinations that there was indeed a difficulty, but they overcame it. Some saw their learning disability as a restriction, a handicap, and stressed the necessity of coping with a “restriction” or “a difficult feature,” a highlighting that characterized the students who were still deep in the difficulty, in the middle of the process. Those who internalized the disabi- lity and accepted it, described a situation of “transfer from diffi- culty to success”, “overcoming difficulty” their descriptions showing flow, motion, riding, a long run without stops, or climbing stairs. The difficulty was mentioned in all the descrip- tions, but also the finish line or summit, and the pride that was felt when looking back at the results. The great upheaval was felt in what Batya said, when in eleventh grade she said angrily, “No! I have no difficulty” when asked if she thought that she had difficulties. In twelfth grade she said that matriculation exams were basically like a “corrective experience”. She came to terms, moderately, with the difficulty and correctly accepted her learning disability as part of her growing up and her self- perception. This is what she said in the final interview, at the end of the end of the twelfth grade: “If I need (accommodations) why not [take them]? It’s like why should I feel ashamed of it or something... I was really ashamed at first, really. I was really, really ashamed at first but now when I think about it I say, like, what was I ashamed about, it is like what we learned in civics, it is “affirmative action.” (Batya) Batya’s words show that she made the transfer from a conception focused on difficulty to a conception that expresses reconciliation, acceptance and a feeling of higher self-esteem. Even the titles students gave to their life stories reveal the stage they were at, since the titles were in accordance with the previously chosen images and show whether they were still focused on the difficulty or had moved to focus on the process of acceptance. This insight could help educators match the treatment to the student’s needs. The data is presented in Table 1. The Story of My Life In the final interview at the end of twelfth grade students were asked to give a title to their life story. Some students were still focused on diffi cu lty. These are the names they gave: Ofra: The never-ending story Tali: Here it all started but it did not end Michal: The difficult years David: The three difficult years Adam: The war of survival Other students were focused on the process of coping and overcoming difficulty. These are the names they gave: Danny: Descending for the need of ascending Odeya: A descent with an ascent at its end Batya: The story that started badly and ended well Eli: Overcoming—the story of an unidentified child Uri: Overcoming the difficulty Martin: A child who overcame, or, A story of overcoming Nir: Overcoming Chaim: Overcoming in spite of everything Aviya: From exile to redemption—a process of self-dis- covery Zohar: The success that followed the failure Two students were focused on success: Michael: A story of success Aviad: A story of success Three students gave a name that shows a conclusion they reached or an insight for life: Na’amah: The way to life Sarah: Do no t despair Offer: The art of education Discussion During this study an attempt was made to outline the journey of the individual in his or her passage through the educational system. Early detection and identification of learning disability and the emotional problems that may accompany it, as well as appropriate intervention, are essential for arming young people to effectively cope with learning disability during high school and beyond. This research demonstrated that students’ perception of the situation, as either a threat or a challenge, is a main factor in their selection of coping style—coping with the learning diffi- culty itself and with the feelings that accompany the difficulty. The selection of coping strategies is related to a variety of in- gredients. The main ingredient is the stage of acceptance of the disability and processing the sense of loss that accompanies diagnosis. It is important to look at the student’s feelings, which are natural to loss or grief, as well as other factors such as personality structure, family system, social environment and school system. It appears that the day of the significant diagnosis, the speci- fic day that a student receives th information about the disabi- e Copyright © 2013 SciR e s . 382  S. GIVON Copyright © 2013 SciRe s . 383 Table 1. How figurative language reveals the stage of acceptance of learning disability and methods of copying: from diagnosis to acceptance. Stage Response and Action Characteri stics of Figurative Language Examples Directions for Intervention Denial, blaming Inability to provide an image; negative words about the disability; images of a criminal dossier I have no difficulty; it’s not hard for me; I don’t have a learning disability; I have n o idea how to give an im age because I don’t have a problem; it’s a whole bunch of things that got thrown at me ; lik e a file they created on me in order to categorize me, a label they stuck on me Developing self-awareness: defining the disability and presenting the idea of recruiting resources t o deal with difficulty Stage 1: The shock of diagnosis: Denial and lack of understanding of the disability Disregarding the disability Comparison with coping with other di f f i culties in life Not relevant; like any difficulty; jus t another one of the difficulti es one has to cope with; another stage of life; like coping with life Developing academ i c competenc e: realistic understanding of the disability and its implications Focus on the process Flow, running, endless galloping movement; path with no exit; ascending and climbing to no destination Like running 2000 m. without stopping; endless war; going up and down stairs and never g etting anywhere; like learning to drive; like a horse with a rider spurring it – the horse wants the rider to ge t off but it goes on and on Setting re alistic goals and providing effective strateg ies: realistic dispersal of pressure and investment in the correct places Stage 2: Adaptation: Understandi ng the nature of the disability; partial readiness to recruit inner resources to ward cognitive a n d emotional cop- ing Focus on the difficulty Being stuck, obstruction, lack, limit, difficult characteristic, heavy burden, war before explosion Like walk in g around with 5 gallons on your back; like a man with his hands tied behind his bac k; li k e a man with a hole in his heart; like a dim screen that you have to get by with; like s omething in your brain that is about to explode; a pressure co ok er about to explode Breaking through emotional barr ie rs and being “stuck” at the difficulty: emotional support for the passage from the fe eling of threa t t o learning challenge, and belief in ability to defend one’s self Focus on coping with the difficulty Difficulty of the passage itself from difficulty to success Overcoming difficulty; a difficult thing that you have no choice but to do; a difficult and frustrating thing that i s always there; coping with a difficult thing that is holding you back in life; something that is difficult in the beginning and the easy; like a puzzle with lo ts of pieces – it’s difficult at the beginning and then as it be gins to fit together it gets easy Inclusion of the disability as part of self-image: emotional support and “straight talk” about t h e nature of the difficulty ; narrative therapy whose goal is freeing the stude n t toward complete acceptance; realistic coping with difficult y; identifying the difficulty as one characteristic that is part of a positive self-i mage; con- structing a positive self-image Stage 3: Complete acceptance of the disability; readiness to accept and use accommodations the educational system provides and insistence on the right to receive them Focus on success a nd thoughts about the future Finish line, reaching the summit and looking back with satisfaction, good experience, redem ptio n Like a long road and you finally reach the finish line; something that requires you to marshal your resources toward a specific goal; like climbing a great peak an looking back at where you came from and saying, “I did that”; like reading the Torah at your bar m itzvah, it gets easier as you go along an d in the end it’s a corrective experience; like the Exodus from Egypt Setting directions and goals for the future: effective preparation for university studies; recruiting determination to realize realistic goals f o r the future lity that he or she has, is an important turning point. If delivery of the information is done properly and accompanied by the right emotional assistance, it has the potential to motivate the process in a positive direction and bring it to the stage of reconciliation and the attribution of appropriate meaning to the situation, such that the student learns to contain the disability as one part of self-perception and treat it as a particular feature, one that makes normal learning more difficult, but something that she/he has the power to cope with. Recruiting and mobili- zation of forces depends on the place that the student allocates to the learning disability within his or her personal world. This study indicates the need to hear the voices of students, learn from them about the ways to cope, what helps them succeed and what drives the process be tter so th ey can re ach the st ag e of reconciliation. In order to understand where and how to inter- vene properly, educators must take into account all the factors involved, such as fear of labeling, personality characteristics, cultural norms and different styles of coping. Proper inter- vention tailored to the stage of acceptance of the disability which the student is at, and to the coping style, will help in  S. GIVON deve- loping optimal intervention program. One fruitful method that can help in detecting the stage of acceptance of disability and the style of coping is open dialogue with the student and the suggestion that students describe their experiences by using figurative language. Figurative language gives expression to overt and hidden feelings that help the edu- cational professional focus on what is needed to help a student emotionally as well as academically. Promoting the emotional process is key to breaking through the obstruction that delays progress during complex academic learning. Optimal treatment-intervention and optimal emotional ad- vancement, as opposed to just promotion of learning in high school students with learning disabilities, will help them in the future in adaptive integration into university, in order to turn their future understanding of higher education from threat to challenge. Conclusion This study found that Figurative Language is an important and effective tool for identifying learning-disabled adolescents’ stage of acceptance of their disability. It also helps to identify the coping style chosen by the adolescent to manage the disa- bility. Accurate identification of the stage and coping style can be a Springboard for Treatment and can help strengthen the student emotionally and academically. It is therefore recom- mended that the tool be used in schools for detection and treat- ment with learning disabled students. One limitation of the stu- dy is the narrow age range researched. Future studies should examine other age groups such as elementary and junior high school students, in order for the tool to be used for detection and preventive care before students reach high school. Pretreat- ment will help adolescents cope better with the challenges of high school. REFERENCES Abouserie, R. (1994). Sources and levels of stress in relation to locus of control and self esteem in university students. Educational Psycho- logy, 14, 323-330. doi:10.1080/0144341940140306 Bailey, J., Barton, B., & Vignola, A. (1999). Coping with children with ADHD: Coping styles of mothers with children with ADHD or challenging behaviors . Early Child Development and Care, 148, 35- 50. doi:10.1080/0300443991480104 Bloom, E., & Heath, N. (2010). Recognition, expression, and under- standing facial expressions of emotion in adolescents with nonverbal and general learning disabilities. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 43, 180-192. doi:10.1177/0022219409345014 Chapman, J. W. (1988). Cognitive-motivational characteristics and aca- demic achievement of learning disabled children: A longitudinal study. Journal of Educational Psychology, 8 0 , 357-365. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.80.3.357 Court, D., & Givon, S. (2003). Group intervention: Improving social skills of adolescents with learning disabilities. Teaching Exceptional Children, 36, 50-55. Dorfman, C. M. (2001). Social language and theory of mind in children with nonverbal learning disability. Dissertation Abstracts Interna- tional, 6, 574B ( UMI No. 3001820). Dyson, L. L. (1996). The experiences of families of children with learn- ing disabilities: Parental stress, family functioning and sibling self- concept. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 29, 280-286. doi:10.1177/002221949602900306 Dyson, L. (2010). Unanticipated effects of children with learning dis- abilities on their families. Learning Disabilities Quarterly, 42-54. Elitzur, A. (1986). Birds inside the head, butterflies inside the stomach and other animals, the use of figurative language in the treatment process. Lectures, 6, 157-166. (Hebrew) Ellis, E. S., & Larkin, M. J. (1998). Strategic instruction for adolescents with learning disabilities. In B. Y. L. Wong (Ed.), Learning about learning disabilities (2nd ed., pp. 585-656). San Diego: Academic Press. Ellis, E. S., & Siegler, R. S. (1997). Planning as a strategy choice, or why don’t children plan when they should? In S. L. Friedman, & E. K. Scholnick (Eds.), The developmental psychology of planning: Why, how, and when do we plan? (pp. 183-208). Mahwah, NJ: Law- rence Erlbaum. Frith, U. (1999). Paradoxes in the definition of dyslexia. Dyslexia: An International Journal of Research and Practice, 5, 192-214. Garmezy, N., & Masten, A. S. (1991). The protective role of compe- tence indicators in children at risk. In E. M. Cummings, A. L. Greene, & K.H. Karraker (Eds.), Life-span developmental psychology: Per- spectives on stress and coping (pp. 151-174). Hillsdale, NJ: Law- rence Erlbaum. Gerber, P. J. (1994). Researching adults with learning disabilities from an adult-development perspective. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 27, 6-9. doi:10.1177/002221949402700103 Gerber, P. J., Ginsberg, R., & Reiff, H. B. (1992). Identifying alterable patterns in employment success for highly successful adults with learning disabilities. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 25, 475-487. doi:10.1177/002221949202500802 Gibton, D. (2001). Grounded theory: The meaning of the data analysis process and building theory in qualitative research. In N. Tazabar- Ben Yehoshua (Ed.), Traditions and trends in qualitative research (pp. 227-195). Lod: Dvir. (Hebrew) Greenham, S. L. (1999). Learning disabilities and psychosocial adjust- ment: A critical review. Child Neuropsychology, 5, 171-196. doi:10.1076/chin.5.3.171.7335 Gregg, N., Hoy, C., & Gay, A. F. (1996). Adults with learning disabili- ties: Theoretical and practical perspectives. New York: Guilford Press. Gregg, N. (2007). Underserved and unprepared: Postsecondary learning disabilities. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 22, 219-228. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5826.2007.00250.x Huntington, D. D., & Bender, W. N. (1993). Adolescents with learning disabilities at risk? Emotional well-being, depression, suicide. Jour- nal of Learning Disabilities, 26, 159-166. doi:10.1177/002221949302600303 Rogers, H., & Saklofski, D. H. (1985). Self-concepts, locus of control, and performance expectation of LD children. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 18, 273-277. Israeli Ministry of Education (2003). Accommodations on testing me- thods for examinees with learning disabilities (Internal). Jerusalem: The Director Gener al’s circular: Standing Orders 4 (b). Lackaye, T., & Margalit, M. (2006). Comparisons of achievement, ef- fort, and self-perceptions among students with learning disabilities and their peers from different achievement groups. Journal of Learn- ing Disabilities, 39, 432-446. doi:10.1177/00222194060390050501 Lackaye, T., Margalit, M., Ziv, O., & Ziman, T. (2006). Comparisons of self-efficacy, mood, effort, and hope between students with learn- ing disabilities and their non-LD-matched peers. Learning Disabili- ties Research & Practice, 21, 111-121. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5826.2006.00211.x Little, L. (1999). The misunderstood child: The child with a nonverbal learning disorder. Journal of the Society of Pediatric Nurses, 4, 113- 121. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6155.1999.tb00044.x Madaus, J., Gerber, P., & Price, L. (2008). Adults with learning dis- abilities in the workforce: Lessons for secondary transition programs. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 23, 148-153. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5826.2008.00272.x Mather, N., & Gregg, N. (2006). Specific learning disabilities: Clarify- ing, not eliminating, a construct. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 37, 99-106. doi:10.1037/0735-7028.37.1.99 Maqsud, M. (1993). Relationships of some personality variables to academic attainment of secondary school pupils. Educational Psy- chology, 1, 11-18. doi:10.1080/0144341930130102 Copyright © 2013 SciR e s . 384  S. GIVON Copyright © 2013 SciRe s . 385 Margalit, M. (1996). Development trends in special education: Pro- moting coping with loneliness, friendships and s e n s e o f c o h e rence. In D. Chen (Ed.), Education towards the twenty-first century (pp. 501- 489). Tel-A viv : R amot. (Hebrew ) Margalit, M., Efrati, M., & Danino, M. (2002). Accommodations in exams for students with learning disabilities: Review of the research and its implications. Educational Co un se lin g, 11, 63-48. (Hebrew) Mooney, S. P., Sherman, M. F., & Lo Presto, C. T. (1991). Academic locus of control, self-esteem, and perceived distance from home as predictors of college adjustment. Journal of Counseling and Devel- opment, 69, 445-448. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6676.1991.tb01542.x National Joint Committee on Learning Disabilities (1994). Collective perspectives on issues affecting learning disabilities. Position pa- pers and statements (2nd ed.). Austin, TX: PRO-ED. (ERIC Docu- ment Reproduction Service No. ED385079). Olsen, M. H. (2010) Metaphors and their relevance to special education. Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research, 1-15. Palombo, J. (2001). Learning disorders and disorders of the self in children and adole s c e n t s . New York: Norton. Pelletier, P. M. (2001). NLD and BPPD: Rules for classification and a comparison of psychosocial subtypes. Dissertation Abstracts In- ternational, 61, 5030B (UMI No. NQ52437). Petti, V. L., Voelker, S. L., Shore, D. L., & Hayman Abello, S. E. (2003). Perception of nonverbal emotion cues by children with non-verbal learning disabilities. Journal of Developmental and Physical Dis- abilities, 15, 23-36. doi:10.1023/A:1021400203453 Rothman, H. R., & Cosden, M. (1995). The relationship between self- perception of a learning disability and achievement, self-concept and social support. Learning Disability Quarterly, 18, 203-2 12. doi:10.2307/1511043 Rourke, B. P. (1995). Syndrome of nonverbal learning disabilities: Neurodevelopmental manifestations. New York: Guilford Press. Seidman, I. E. (1998). Interviewing as qualitative research: A guide for researchers in education and the social sciences (2nd ed.) New York: Teachers College Press. Sobel, S. (2006). The world of figurative language of the learning dis- abled in treatment: Conceiving the self and the academy, conceiving the learning disability and sense of coherence. MA Thesis, Haifa: Haifa University. (Hebrew) Sterbin, A., & Rakow, E. (1996). Self-esteem, locus of control and student achievement. Paper Presented at the Annual Meeting of the Mid-South Educational Research Society, Tuscaloosa, AL, Novem- ber 1996. Strauss, A. L. (1987). Qualitative analysis for social scientists. Cam- bridge: Cambridge University Press. Taymans, J., Swanson, H., Schwarz, R., Gregg, N., Hock, M., & Gerber, P. (2009). Learning to achieve: A review of the research literature on serving adults with learning disabilities. The National Institute for Literacy, Washington DC. Young, K. M. (1975). The self and the subconscious. Translated from German into Hebrew by Chaim Isaac. Tel Aviv: Dvir.  S. GIVON Appendix Guide to Interview 1: semi-structured in-depth interview conducted for participants in the tenth grade before matri- culation exams: I’m interested in the life stories of the students taking their matriculation exams while using accommodations. Please tell me the story of your life since you recall to this day. Specific Questions (According to the Subjects that Students Bring Up) History of education: First signs of difficulty, the response of the surrounding and the coping. Who located the difficulty, in what grade and how? What did you use as educational assistance - how effective was it? Replies of the family, friends and teachers at the various stations at school. What grade did you formally started using the accommo- dations and how did the surrounding respond? How did the transfers between educational frameworks affect you, in the context of learning difficulties? Concept of learning disability and its effects: When were you diagnosed (the full diagnosis), what were you told and how did your parents react? Can you define the difficulty and what is it like? How did friends react and when did you, decide, if ever to share the information with them? Describe positive and negative experiences in the context of the disa bi lity. How do you cope today with learning and with responses from the surrounding? What do you do at leisure—do you have other occupations? Vision for the Future What is your chance of success in matriculation exams? How do you see yourself in future practice? What will you advise another child who started high school and is in your sit uation? How will the difficulty affect your choice of profession? What would you like to do “when you grow up”? Interview Guide 2: Semi-Structured In-Depth Interview for Eleventh Grade Students before Matriculation Exams An Open Question A year has passed since we met the day before Passover last year. I’m still interested in what goes on with students who struggle with matriculation exams while using the accommo- dations. Please tell me what happened since we parted until today. Specific Questions (According to the Subjects That Students Bring Up) Description of cognitive coping with matriculation exams; How do you prepare for the tests/and what are the support systems you use within and outside the school? Describe the test event and what you thought before/after it. Describe your daily routine during the tests. Describe how to cope, in your learning and emotionally, with academic stress. Describe a situation where you felt a change in your attitude towards yourself and towards the school. Support of parents, teachers, family—who helped you par- ticularly? Friends’ attitude—social coping—social activities outside of school and in leisure. Description of the way the accommodations were used, their effectiveness, how the school organized for that and the response of the surrounding. Describe difficulties - what is difficulty un learning? Give an image to the difficulty: for me to study for the matriculation exams is like… Describe the experience of coping with learning - how it puts you in compare of the others? Implications for the Future Results against expectations—what is the feeling? Are the grades so far compatible with the expectations? Description of an event—the day when he/she received the results and his/her personal response/reaction of the surround- ing/parents. Thoughts about the continued success in matriculation exams and the extent of investment required. Thoughts about the chances of success in adulthood. Tips to another child who has difficulties and is in the be- ginning of the way. Plans for the future and how learning disability will affect the choice of profession. Message to the school and teachers. Interview Guide 3: Semi-Structured In-Depth Interview with Students in the Twelfth Grade An Open Question A year has passed since we parted the day before Passover last year. I’m still interested in what goes on with students who struggling with matriculation exams while using the accom- modations. Please tell me what happened since the day we parted until today. Specific Questions (According to the Subjects that Students Bring Up) Description of experience and difficulties: Description of test preparation, support systems and daily routines. Compare 10th grade, 11th grade and 12th frade (senior year in terms of emotional and cognitive coping.Use of the accom- modations, the attitude of teachers, friends and estima- tion of the extent of effectiveness and organizing. Observing the experience—a description of things that have changed/if cha nged: The attitude of the society, parents, teachers. The role of counselor/psychologist/diagnosist. Self-Perceptions I as compared to the others—self-perception in relation to peer group. Copyright © 2013 SciR e s . 386  S. GIVON Copyright © 2013 SciRe s . 387 Perception of disability and its impact on coping with learn- ing. Are the results consistent with expectations so far? New Insights and Vision for the Future Thoughts of the future—how difficulty will affect occu- pational or profession choices. How will the difficulty or what you learned from your coping on your future and your life? Will you use accommodations out of school, in future learning? Thinking back—what was most helpful to you? What is the message to school, and what advice will you give to a child with a learning disability in the beginning of his way? Give an image to your coping: For me, to pass the matri- culation exams, was like: _________________ What would you like/want to contribute to others from your experience? Plans for next year and their connection to what you went through. The process you went through—Name the story: Choose a name for yourself:

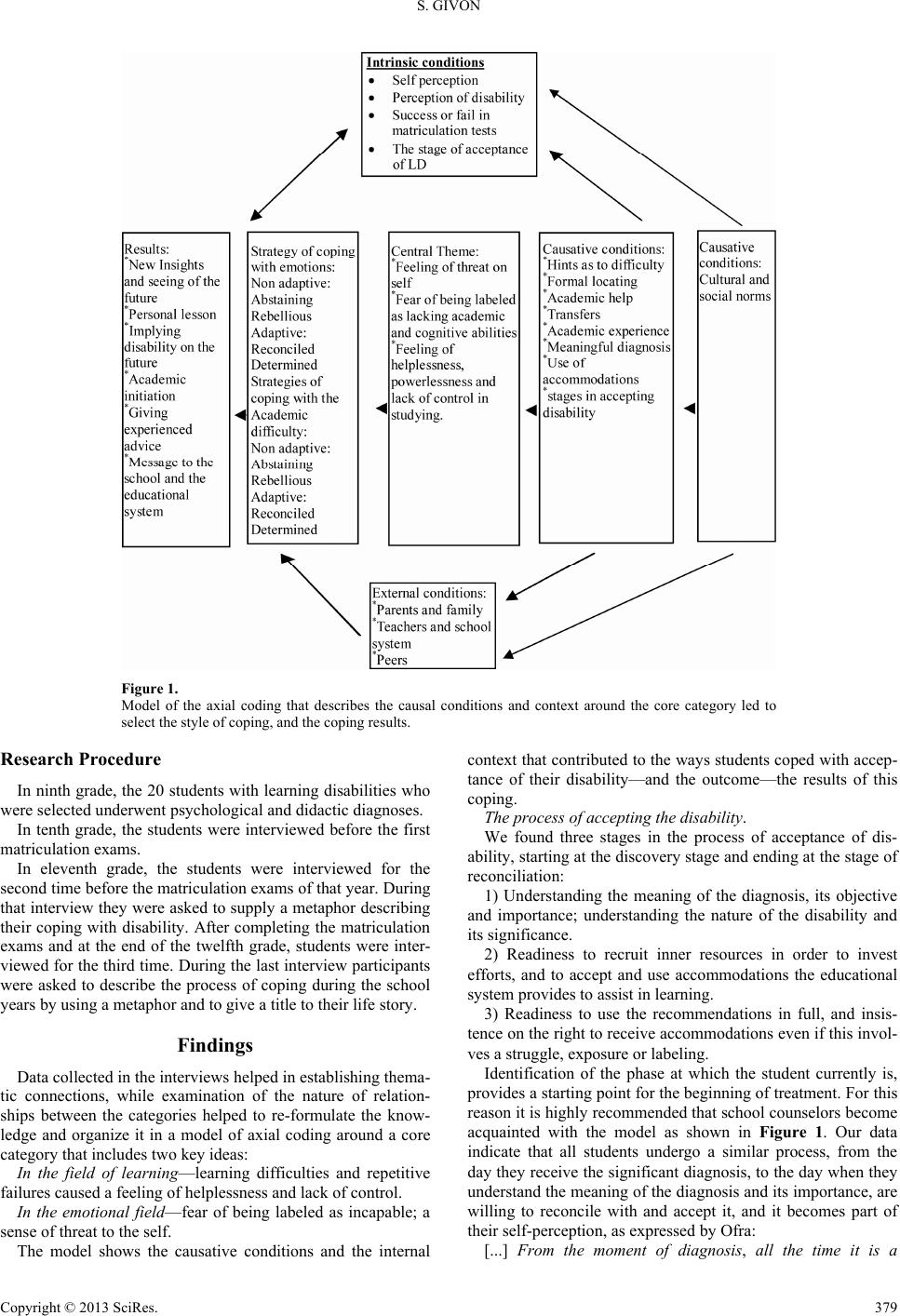

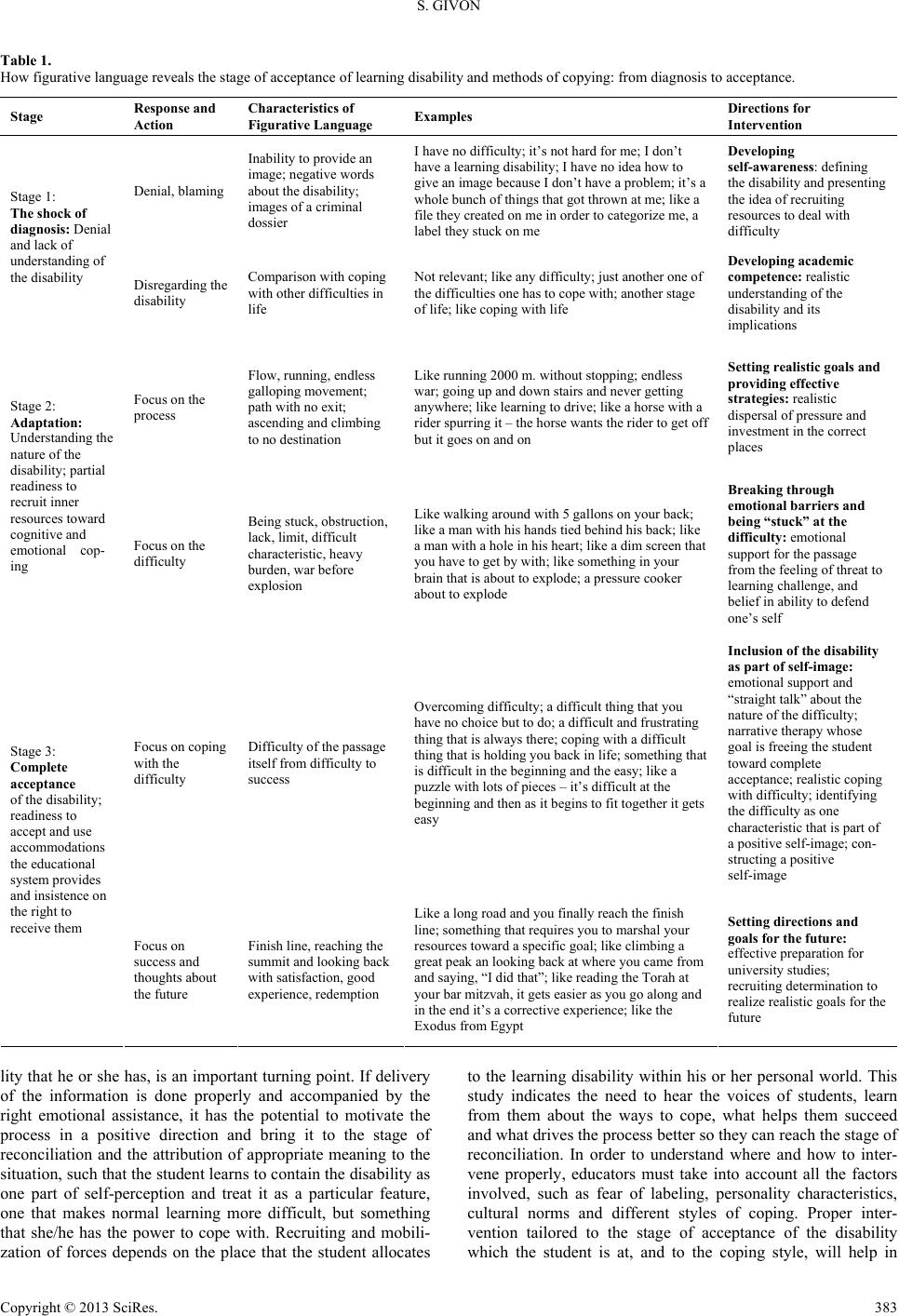

|