Perforation of the Nasal Septum and Nasal Ulcers29

Centre for PCR study and specific Leishmania culture.

Pending the outcome of specific cultures, empirical

therapy was replaced with liposomal amphotericin B 3

mg/kg/day (six weekly doses with a received dose of 900

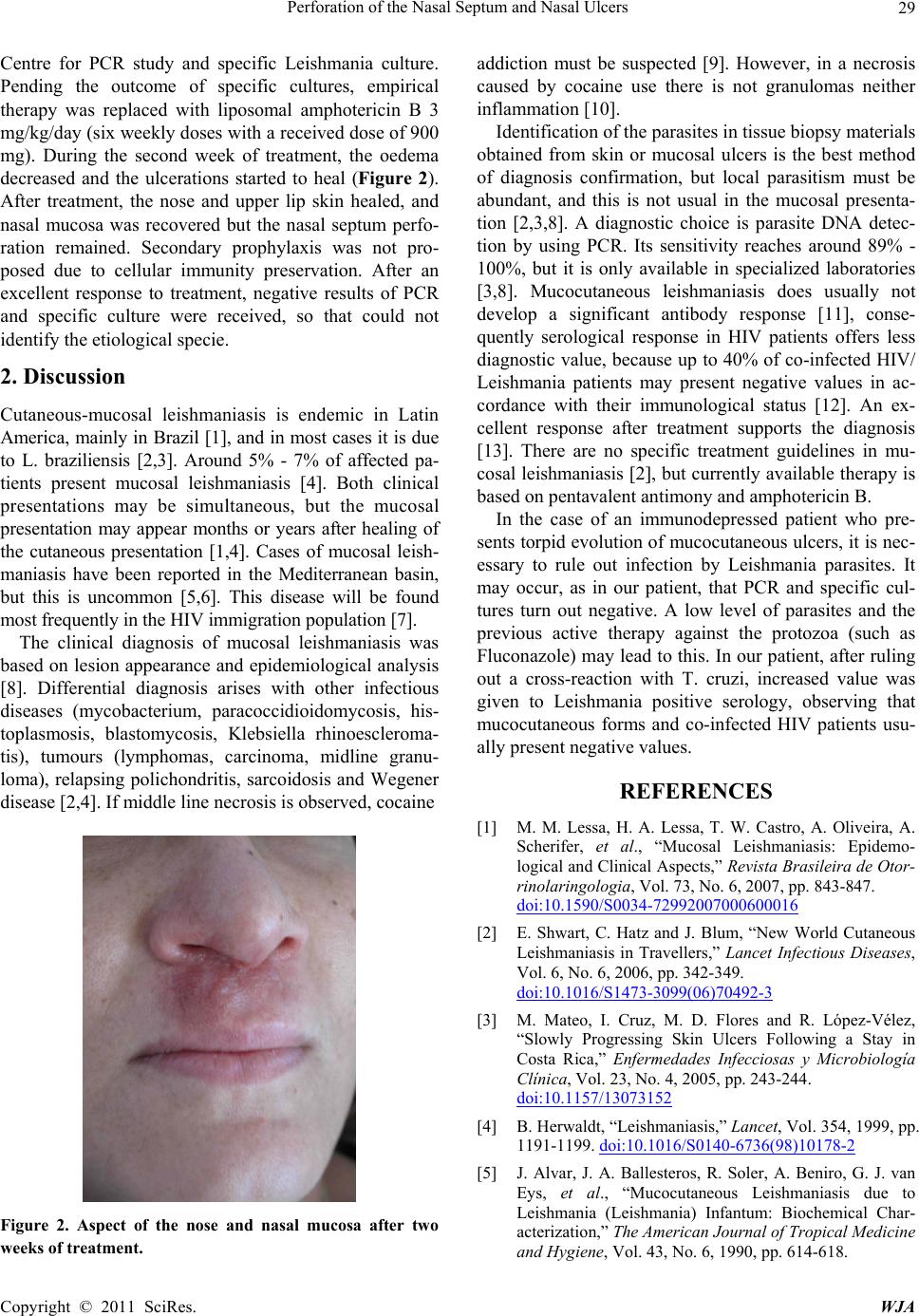

mg). During the second week of treatment, the oedema

decreased and the ulcerations started to heal (Figure 2).

After treatment, the nose and upper lip skin healed, and

nasal mucosa was recovered but the nasal septum perfo-

ration remained. Secondary prophylaxis was not pro-

posed due to cellular immunity preservation. After an

excellent response to treatment, negative results of PCR

and specific culture were received, so that could not

identify the etiolog ical specie.

2. Discussion

Cutaneous-mucosal leishmaniasis is endemic in Latin

America, mainly in Brazil [1], and in most cases it is due

to L. braziliensis [2,3]. Around 5% - 7% of affected pa-

tients present mucosal leishmaniasis [4]. Both clinical

presentations may be simultaneous, but the mucosal

presentation may appear months or years after healing of

the cutaneous presentation [1,4]. Cases of mucosal leish-

maniasis have been reported in the Mediterranean basin,

but this is uncommon [5,6]. This disease will be found

most frequentl y i n t he HIV immigrati on po pul at i on [7] .

The clinical diagnosis of mucosal leishmaniasis was

based on lesion appearance and epidemiological analysis

[8]. Differential diagnosis arises with other infectious

diseases (mycobacterium, paracoccidioidomycosis, his-

toplasmosis, blastomycosis, Klebsiella rhinoescleroma-

tis), tumours (lymphomas, carcinoma, midline granu-

loma), relapsing polichondritis, sarcoidosis and Wegener

disease [2,4]. If middle line necrosis is observed, cocaine

Figure 2. Aspect of the nose and nasal mucosa after two

weeks of treatment.

addiction must be suspected [9]. However, in a necrosis

caused by cocaine use there is not granulomas neither

inflammation [10].

Identification of the parasites in tissue biopsy materials

obtained from skin or mucosal ulcers is the best method

of diagnosis confirmation, but local parasitism must be

abundant, and this is not usual in the mucosal presenta-

tion [2,3,8]. A diagnostic choice is parasite DNA detec-

tion by using PCR. Its sensitivity reaches around 89% -

100%, but it is only available in specialized laboratories

[3,8]. Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis does usually not

develop a significant antibody response [11], conse-

quently serological response in HIV patients offers less

diagnostic value, because up to 40% of co-infected HIV/

Leishmania patients may present negative values in ac-

cordance with their immunological status [12]. An ex-

cellent response after treatment supports the diagnosis

[13]. There are no specific treatment guidelines in mu-

cosal leishmaniasis [2], but currently availab le therapy is

based on pentavalent antimony and amphotericin B.

In the case of an immunodepressed patient who pre-

sents torpid evolution of mucocutaneous ulcers, it is nec-

essary to rule out infection by Leishmania parasites. It

may occur, as in our patient, that PCR and specific cul-

tures turn out negative. A low level of parasites and the

previous active therapy against the protozoa (such as

Fluconazole) may lead to this. In our patient, after ruling

out a cross-reaction with T. cruzi, increased value was

given to Leishmania positive serology, observing that

mucocutaneous forms and co-infected HIV patients usu-

ally present negative values.

REFERENCES

[1] M. M. Lessa, H. A. Lessa, T. W. Castro, A. Oliveira, A.

Scherifer, et al., “Mucosal Leishmaniasis: Epidemo-

logical and Clinical Aspects,” Revista Brasileira de Otor-

rinolaringologia, Vol. 73, No. 6, 2007, pp. 843-847.

doi:10.1590/S0034-72992007000600016

[2] E. Shwart, C. Hatz and J. Blum, “New World Cutaneous

Leishmaniasis in Travellers,” Lancet Infectious Diseases,

Vol. 6, No. 6, 2006, pp. 342-349.

doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70492-3

[3] M. Mateo, I. Cruz, M. D. Flores and R. López-Vélez,

“Slowly Progressing Skin Ulcers Following a Stay in

Costa Rica,” Enfermedades Infecciosas y Microbiología

Clínica, Vol. 23, No. 4, 2005, pp. 243-244.

doi:10.1157/13073152

[4] B. Herwaldt, “Leishmaniasis,” Lancet, Vol. 354, 1999, pp.

1191-1199. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(98)10178-2

[5] J. Alvar, J. A. Ballesteros, R. Soler, A. Beniro, G. J. van

Eys, et al., “Mucocutaneous Leishmaniasis due to

Leishmania (Leishmania) Infantum: Biochemical Char-

acterization,” The American Journal of Tropical Medicine

and Hygiene, Vol. 43, No. 6, 1990, pp. 614-618.

Copyright © 2011 SciRes. WJA