Communications and Network

Vol.5 No.4(2013), Article ID:39581,11 pages DOI:10.4236/cn.2013.54038

A Novel Outage Capacity Objective Function for Optimal Performance Monitoring and Predictive Fault Detection in Hybrid Free-Space Optical and RF Wireless Networks

Department of Physics and Engineering Physics, Stevens Institute of Technology, Hoboken, USA

Email: bschmidt@stevens.edu

Copyright © 2013 Barnet M. Schmidt. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Received July 18, 2013; revised August 15, 2013; accepted August 21, 2013

Keywords: Free-Space Optical Networks; Outage Capacity; Hybrid Networks; Performance Monitoring; Fault Management; MIMO; Wireless Networks; Network Management

ABSTRACT

This study develops an optimal performance monitoring metric for a hybrid free space optical and radio wireless network, the Outage Capacity Objective Function. The objective function—the dependence of hybrid channel outage capacity upon the error rate, jointly quantifies the effects of atmospheric optical impairments on the performance of the free space optical segment as well as the effect of RF channel impairments on the radio frequency segment. The objective function is developed from the basic information-theoretic capacity of the optical and radio channels using the gamma-gamma model for optical fading and Ricean statistics for the radio channel fading. A simulation is performed by using the hybrid network. The objective function is shown to provide significantly improved sensitivity to degrading performance trends and supports of proactive link failure prediction and mitigation when compared to current thresholding techniques for signal quality metrics.

1. Introduction

Current techniques of free-space optical (FSO) and radio frequency (RF) link performance measuring and monitoring are traditionally applied at the physical and lower link layer, at the RF and FSO signal in space (SiS) and at the bit/packet levels. Performance metrics commonly used include received signal level, optical signal-to-noise ratio (OSNR) for the optical links, quality (Q) factor, eye diagram, signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) or signal-to-interference ratio (SIR) for the RF links, and bit error rate (BER). Traditional methods of link health analysis include observation of these parameters in attempt to determine their trends. In good atmospheric conditions the received optical signal level and OSNR will be high and will fluctuate within some previously-defined normal range as determined by the optical channel fading characteristics. In good RF propagation conditions, the received signal level will be correspondingly high as the SNR/SIR, and in turn it will also fluctuate within a bounded acceptable range. Degrading optical conditions of the atmosphere will in turn degrade the received optical signal level and OSNR. Degrading RF propagation conditions, such as fading and multipath will have similar effects upon the received signal level, SNR, and/or SIR.

The error correcting codes (ECCs) used in most digital communications systems provide excellent performance until a specific threshold of SNR is exceeded at which point the error rate increases rapidly. In most cases, by the time the performance monitor (PM) component of the network management system (NMS) has determined that the SNR and other performance metrics have crossed the acceptable threshold, user data are lost. Current methods of thresholding by themselves are therefore inadequate to predict link failure.

In poor transmission conditions the NMS institutes corrective actions consisting of reducing the transmitted data rate, increasing the signal power, instituting more frequent retransmissions (usually managed independently by the link layer protocol used in the network), or combinations of these techniques. Traffic offloading and rerouting may also be used to reassign traffic and better performing links in lieu of those with degraded performance temporarily until transmission conditions improve and the PM observes the performance metrics to once again cross their acceptable thresholds.

The optimal performance monitoring function developed in this study is the Outage Capacity Objective Function (“Objective Function”). The objective function is defined as the outage capacity of the hybrid FSO/RF channel as a function of BER. It is demonstrated that the objective function provides an extremely sensitive measure of the network performance, identifying impending failure well in advance of signal quality thresholding alone.

2. Network Topology and Characteristics

This hybrid FSO and radio wireless network considered in this study has the topology shown in Figure 1. The network characteristics are described below:

1) Wavelength, Frequency, and Structure: The FSO channels operate at the “long” mid-infrared (MIR) wavelength of 10,000 nm. Studies in this range of wavelengths predict improvements in performance over shorter wavelengths (see Related Work, below). The frequency of the RF channels is 1.9 GHz, a widely used band in cellular radio systems.

2) Propagation: Line-of-sight (LOS) propagation is assumed for both the FSO and RF links.

3) Cellular Topology: The RF segment utilizes a cellular topology with 12 cells and K users per cell. Handoff is used as in commercial cellular systems.

4) MIMO: The FSO channels are analyzed for the single input-single output (SISO) case using only one transmitter and receiver, and the multiple input-multiple output (MIMO) case. The objective function is produced for both SISO and several MIMO levels.

Each RF transceiver is capable of communicating with the co-located FSO transceiver using a baseband digital

Figure 1. Hybrid network topology.

link. This allows the optical and RF transceivers to balance user traffic between the FSO and RF links (for simplicity these cross-links are not shown on the network diagram).

3. Outage Capacity

The outage capacity, C, for both the optical and RF channels is defined as the maximum throughput (load) that the hybrid channel can support at a given BER:

(1)

(1)

The outage capacity of the optical and RF channels is determined from the application of information theory to the fading statistics of the channels.

The optical channel capacity is determined by the instantaneous mutual information of the channel and its fading distribution. Information theory shows that the capacity of the channel is the mutual information of the channel maximized over all possible distributions of inputs. This assertion is valid in the absence of fading. In the presence of fading, the instantaneous capacity of the channel is the product of the instantaneous mutual information conditioned upon the channel information and the instantaneous value of the signal intensity (fading) is determined by the instantaneous mutual information, T(p,x), where x is the instantaneous channel realization given the instantaneous channel state, i, conditioned upon the probability distribution function (PDF) of the irradiance (the fading distribution), fi(x), and p, the power distribution of the N MIMO transmitters:

(2)

(2)

Rewriting the outage capacity in terms of the mutual information and the fading distribution:

(3)

(3)

3.1. Related Work

MIR wavelengths have been shown to improve FSO performance due to lower Mie scattering losses in [1] and [2]. Studies [2,3], and [4] have demonstrated that atmospheric FSO channel fading is accurately characterized by the Gamma-Gamma distribution. In the gamma-gamma statistics two independent fading models that characterize the fading effect of strong and weak turbulence, including scattering and scintillation are used. Each of the distributions is a gamma distribution and is an extension of prior studies that establish a doubly-stochastic model as the optical fading channel. Influence of diversity methods on the RF channels has been studied in [5]. Performance improvements in FSO at MIR wavelengths are considered in [6]. Effects of atmospheric turbulence, as well as further support of the Gamma-Gamma fading distribution on FSO channel capacity have been studied in [7] and [8]. The effect of pointing errors and misalignment on the outage capacity of purely FSO channels has been investigated in [9] and [10].

3.2. Instantaneous Mutual Information

The instantaneous mutual information of the channel is a measure of the dependence between the random variables that characterize the channel: p, i, and x (4):

In the information-theoretic sense, the mutual information quantifies the degree to which knowing any of the random variables p, x, and/or i reduces the uncertainty about the others. In many analyses of channel capacity (including this one) and/or error performance knowledge of the channel state i increases the mutual information. When channel state is unknown or unreliable, estimation methods may be used to obtain these values.

The channel capacity is the instantaneous mutual information of the channel maximized over all possible distributions of the transmitted information:

(5)

(5)

Expanding this equation produces (6):

and is used in developing the outage capacity for the gamma-gamma channel. The outage capacity is the maximum throughput of the channel at a given specified error probability (which, in turn, implies a specific BER at that rate).

3.3. Outage Probability

An analytical derivation of the exact outage probability for the gamma-gamma model is an intractable problem in closed form [4]. Instead, the asymptotic behavior of the outage probability as a function of OSNR and the lower bound is investigated.

The error probability with respect to (conditioned upon) the instantaneous mutual information, instantaneous channel realization, and the data rate R can be stated as:

(7)

(7)

The probability of an error at a given OSNR and data rate is simply the probability of the instantaneous mutual information of the channel being less than the data rate. This is intuitive since the instantaneous mutual information of the channel averaged over the inputs represents the information capacity of the channel under the given impairment conditions (that is, OSNR) while the data rate represents the transmission rate required by the user. The Shannon-Hartley theorem imposes an upper bound on the capacity of any channel as a function of the bandwidth and the SNR. The summations in the mutual information Equation (4) may be expressed in terms of the Shannon capacity and (2) rewritten as (8):

where: L is the length of the transmitted block in codewords, zq are additive white Gaussian noise (AWGN) samples with zero mean and variance (normalized power) 1, xq is the channel realization when codeword q is received, and Q is the number of codewords.

The inner term of the summation in (8) is the mutual information of an AWGN channel with an OSNR of . The asymptotic behavior of the outage probability can be determined by introducing the OSNR exponent, defined as:

. The asymptotic behavior of the outage probability can be determined by introducing the OSNR exponent, defined as:

(9)

(9)

where P is the total transmitted power of the M transmitters.

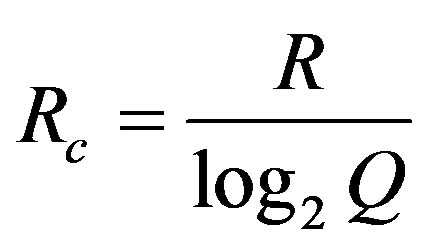

Evaluating (9) using the Shannon capacity while substituting the Shannon-Hartley equation for the rate R yields:

(10)

(10)

where B is the system bandwidth, N is the number of receivers in the MIMO system, and Rc is the binary code rate, which is:

(11)

(11)

A strategy to maximize the outage capacity in the gamma-gamma channel is to allocate the transmitted power among the N transmitters so as to satisfy the condition of (7) being minimized as much of the time as possible.

In this analysis, the transmit power is equally allocated to each of the M transmitters (instantaneous power at each transmitter is 1/M). Allocating the transmitted power to the transmitters is subject to both the short and long term power constraints of the system. In the short term, more power than the total available system power can be allocated to a subset of the transmitters if that optimizes the instantaneous mutual information rate under at that particular OSNR. The long term power, which is the expected value of the short term power, places a limit on how long such short-term allocation can be performed. The SNR exponent corresponding to the long term power constraint is the same as the short-term power constraint SNR exponent when the value of the SNR exponent is less than 1. If the value of the (short-term power constraint) SNR exponent is greater than 1, the long-term SNR exponent is infinite. In this case the outage probability curve slope is infinite and there is an instantaneous increase in the outage probability under these conditions.

The optimal OSNR exponent and thus the outage probability is a strong function of the number of transmitters and receivers in the MIMO system, specifically their product MN. As will be shown in the results, as the number of transmitters and receivers are increased (hence, the product MN) the ultimate floor of the outage probability drops at a sufficiently high OSNR. This demonstrates the value of spatial diversity which is one of the reasons for using a MIMO system. However, the slope of the outage probability curve increases with increasing MN. This results in a tradeoff of the minimum outage probability vs slope or tolerance to OSNR. In systems having low OSNR (which is the usual case for FSO systems) it is advantageous to maximize the number of transmitters and receivers. In this case, the high slope of the outage probability as a function of OSNR can be tolerated since the high OSNR/low outage probability mode will be the usual operating condition. If the system operates over a wide range of OSNR, particularly in low OSNR regime, it is advantageous to have a smaller number of transmitters and receivers. This is borne out by the fact that at low OSNR, the outage probability increases rapidly as the OSNR decreases. In this case, the ultimate minimum outage probability is traded off. If MN were to be large in this case, there would be frequent cases where the outage probability rapidly increases to 1 over a narrow range of (decreasing) OSNR.

3.4. Outage Capacity of the Optical Channel

In considering the effect of the gamma-gamma channel (or any other optical fading channel) it is realized that the received signal irradiance in any fading channel is the equal to the received signal in an AWGN channel scaled by the instantaneous value of the fading. The distribution of the received signal irradiance as previously described is simply the distribution of the signal received from an AWGN channel scaled by the distribution of the fading. This is simply a linear model of the channel, which is an AWGN channel followed by a spatial filter whose optical transfer function replicates the fading. We use this result to determine the instantaneous mutual information of the gamma-gamma channel.

The fading probability distribution function of an AWGN channel is a Gaussian distribution. The instantaneous mutual information of the fading channel is bounded by that of a Gaussian (AWGN) channel. Information theory proves that the Gaussian distribution contains the maximum entropy and therefore also represents the maximum mutual information. As a function of the optical signal irradiance variance  (which is the normalized signal power) and the two-sided noise power spectral density (PSD) No, the instantaneous mutual information becomes:

(which is the normalized signal power) and the two-sided noise power spectral density (PSD) No, the instantaneous mutual information becomes:

(12)

(12)

The upper bound of channel capacity is the outage capacity when conditioned upon the probability of failure. The capacity of the gamma-gamma channel is the upper bound of the mutual information of the Gaussian channel scaled by the filtering of the Gaussian-Gaussian channel. Since the ergodic capacity and the Gamma-Gamma distributions are independent, the upper bound is obtained from the product of the Gaussian mutual information upper bound and Gamma-Gamma distributions and then averaging over the irradiances. In this relationship P is the total transmitted power of the MIMO array, i is the received signal irradiance, ψ is a variable dependent upon the distance between the transmitted symbols in the complex signal space (the square of the incremental distance between the points in the transmitted On-Off Keying (OOK) constellation), and ξ is the normalized power per bit (p/R). The maximum capacity is (13):

In this equation the final product term of the integrand is the gamma-gamma fading distribution. The gamma functions Γ(α) and G(α) quantify the fading contributions from weak and strong turbulence, respectively. The values of α and β are the number of eddy currents in the turbulent atmospheric flow, where a is the number associated with the small-scale refractive index changes and scattering, and β being the number of large scale eddy currents associated with strong turbulence [5]. These parameters depend upon the physical dimensions of the FSO system, the wavelength, transmission distance, and altitude:

(14)

(14)

(15)

(15)

where: ,

,  , and the wave number,

, and the wave number, .

.

D: Diameter of the receiver lens aperture (0.01 m).

L is the transmission distance (1500 m).

is the refractive index structure parameter (1.7 × 10−14, altitude-dependent. The altitude is 100 m. in this study).

is the refractive index structure parameter (1.7 × 10−14, altitude-dependent. The altitude is 100 m. in this study).

The integration in (13) is carried out to produce a closed form solution, resulting in (16):

where:  is Meijer’s G-Function [11].

is Meijer’s G-Function [11].

3.5. Error Rate Performance

The error rate performance of the gamma-gamma channel is determined below. In the MIMO receiver some form of combining must be used to coherently add the received signal energy from each of the receivers in the array. The most frequently used combining method is equal gain combining (EGC). In EGC the outputs of the receivers are equally weighted and summed. While optical beamforming methods have been investigated (using complex weighting of the individual receivers’ outputs in an attempt to maximize the resultant SNR) EGC remains the dominant method. The probability density function (pdf) of the irradiance (gamma-gamma distribution) is a component of the capacity Equation (13). To determine the error probability with combining at the receiver array we need to modify the irradiance pdf considering the combining gain introduced by the receiver array.

The moment generating function resulting from the introduction of diversity combining results a new pdf or conditioned probability that is a function of the gammagamma fading and the diversity combining (the function f(S) incorporates the subchannel state S which is discussed below) (17):

The error probability conditioned upon the irradiance as a function of the transmitted symbol X, the received symbol  and the PSD is:

and the PSD is:

(18)

(18)

where Q(.) is Marcum’s Q function.

Each channel of the MIMO array has its own channel state that is specific to the mth transmitter and the nth receiver which is the subchannel state, . The state of the aggregate MIMO channel S is a linear combination of all the subchannel states for the system consisting of M total transmitters and N total receivers:

. The state of the aggregate MIMO channel S is a linear combination of all the subchannel states for the system consisting of M total transmitters and N total receivers:

(19)

(19)

With EGC, all the receiver outputs,  , are equally weighted. The combined receiver output is therefore:

, are equally weighted. The combined receiver output is therefore:

(20)

(20)

where ε is a sum of Gaussian random variables, xn:

(21)

(21)

Having a variance of:

(22)

(22)

Under the assumption that the channel state information is perfectly known to the receiver the combined receiver output is:

(23)

(23)

where ES is the energy and IS the irradiance per symbol, respectively. Substituting the combined receiver output from (20) into the OSNR in the expression for the conditioned error probability yields:

(24)

(24)

Conditioning with the gamma-gamma fading pdf and averaging over the fading (that is, the entire gammagamma pdf conditioned upon the channel state S) results in the error probability as:

(25)

(25)

Substituting the fading pdf, which is the last term of the gamma-gamma capacity Equation (13) into the conditioned error probability (17) results in the bit error probability for the gamma-gamma channel with scattering, where γ is the Mie scattering coefficient (see Equation (26)).

4. Outage Capacity of the Radio Channel

The radio frequency (RF) segment of the hybrid network is designed using a cellular topology, similar to that of commercial cellular radio systems. In this study, the cellular RF network consists of twelve cell sites, each with N channels. The allocated bandwidth per user is 30 MHz. As with the optical channel, we apply the fundamental capacity limits of information theory to determine the outage capacity given the total allocated bandwidth and SNR.

The RF segment outage capacity is determined for AWGN and Ricean fading channels. Ricean fading is often encountered in urban environments containing buildings and other structures that give rise to shadowing and multipath. The outage capacity is determined using two forms of spatial diversity: transmit diversity and beamforming. The transmit diversity scenarios utilizes EGC while the beamforming scenario utilizes equal weighting of each beam.

4.1. AWGN

Outage capacity was discussed as a measure of link capacity in the optical domain earlier in this paper. As in the optical domain we define the outage capacity as the rate of the channel conditioned upon outage probability. It is the greatest possible data rate with probability 1 – Pr, where Pr is the outage probability:

(27)

(27)

We can now calculate the pdf of the transmit diversity channel capacity is determined using the methods of [5]:

(28)

(28)

Then:

(29)

(29)

where  is a chi-square distribution of the M transmitters, Z is the total SNR, z is the SNR at an individual receiver, and wm and am are the complex weight and amplitude of the mth received signal, respectively.

is a chi-square distribution of the M transmitters, Z is the total SNR, z is the SNR at an individual receiver, and wm and am are the complex weight and amplitude of the mth received signal, respectively.

The pdf of the outage capacity can then be expressed as:

(30)

(30)

For the beamforming case, the pdf of the outage probability as:

(31)

(31)

Using (31), the outage probability is:

(32)

(32)

The outage probability differs between the beamforming and the transmit diversity system in the number of degrees of freedom of the chi-square distribution.

For transmit diversity the number of degrees of freedom contains the factor of M whereas for beamforming it is fixed at 2.

We consider here two measures of channel capacity in the forward link. The maximum normalized channel capacity is the Shannon capacity, which is equal to log2(1+z). Substituting (30) into the Shannon capacity equation we obtain the capacity with transmit diversity as:

| |

(33)

(33)

Note that the integration in the above two equations yields the expected value of the Shannon capacity with respect to the variation of signal-to-noise ratio with the diversity level M. For beamforming, the Shannon capacity is similar to that for receive diversity, with this factor added for the beamforming gain, M:

(34)

(34)

The channel capacity CT for the 12-cell system is the sum of the individual cell capacities Ci across all users:

(35)

(35)

Applying the summation of (35) to (33) and (45) for transmit diversity and beamforming respectively, yields the total system capacity as:

(36)

(36)

(37)

(37)

where  is the total allocated RF bandwidth (30 MHz), M is the total number of rays, and

is the total allocated RF bandwidth (30 MHz), M is the total number of rays, and  and

and  are the signal-to-interference ratios (SIR) at the ith user for transmit diversity and beamforming, respectively.

are the signal-to-interference ratios (SIR) at the ith user for transmit diversity and beamforming, respectively.

4.2. Transmit Diversity in the Ricean Channel

To calculate the capacity with transmit diversity of the RF segment with frequency selective (Ricean) fading, we calculate the distribution of SNR imposed by the Ricean pdf. This yields a Ricean-distributed sequence of ray amplitudes and phases, whose individual capacities we then integrate over the total number of rays, m, to find the total system capacity. The signal envelope of the Ricean fading channel is defined by the pdf [5]:

(38)

(38)

where X is the contribution to the mean signal power of the diffused signal component, t is time, and s is 2ry – vt(0) (where y is average interference-to-noise ratio).

The pdf of the interference-to-noise ratio is the sum of identical interfering signal powers. The pdf of the total interference-to-noise ratio for Ricean fading is thus (39):

where J0 is the zeroth order Bessel function, Y is mean power of ith interferer, and I is the total number of interferers. The channel capacity for transmit diversity with Ricean fading is similar to AWGN case, using the pdf of the SNR in the Ricean channel and the topology of the cellular RF network [5] (40):

4.3. Beamforming in the Ricean Channel

To calculate the capacity of beamforming in the RF segment with frequency selective (Ricean) fading, we calculate the distribution of signal-to-noise ratio resulting from the application of the Ricean fading. This yields a Ricean-distributed sequence of ray amplitudes and phases, whose individual capacities we then integrate over the total number of rays, m, to find the total system capacity.

The Shannon capacity of the RF segment with beamforming is similarly determined to that for the AWGN case, using the pdf of the SNR in the Ricean channel:

(41)

(41)

5. Objective Function

The objective function for the hybrid channel is produced by summing the outage capacity of the optical and RF channels with respect to (w/r/t) to the joint BER. The joint BER is the joint error rate pdf of the optical and RF channels. Since the FSO and RF fading pdfs are independent, the joint BER is the product of the two pdfs.

Figure 2 illustrates the objective function for the hybrid FSO/AWGN RF channel with beamforming. The outage capacity of the hybrid channel, in Mbps, is the sum of (16) and (37). The BER is the product of (26) and the AWGN error probability [7],

:(42)

:(42)

Figure 3 provides the objective function for the Ricean

Figure 2. Objective function—FSO/AWGN beamforming.

Figure 3. Objective function—FSO/Ricean transmit diversity.

RF channel with transmit diversity, The outage capacity of the hybrid channel is the sum of (16) and (40). The BER is the product of (26) and the Ricean error probability with transmit diversity [7],

(43)

(43)

where U is the SIR, UAVG is the average value of U, and δ is the ratio of the power of the diffuse signal components to the direct component.

Figure 4 incorporates the Ricean channel with beamforming. The outage capacity of the hybrid channel is the sum of (16) and (41). The BER is the product of (26) and the Ricean error probability with transmit diversity [7],

(44)

(44)

Figure 4. Objective function—FSO/Ricean beamforming.

where Nb is the number of beams.

6. Simulation

The objective function for the FSO and AWGN RF hybrid channel is simulated using the network described in Section 1. The objective function is characterized for the AWGN and Ricean cases by loading the hybrid channel and observing the BER until failure occurs while evaluating the corresponding outage capacities over the gamut of BER in the simulation model.

The optical and RF channel parameters used in the simulation are provided in Table 1. The optical channels are operated as MIMO using 10 transmitters and receivers. A Gaussian optical pulse shape is used for the FSO channels, while for the RF channels a sinc(x) chip shape is used. The optical transmit power is 200 mW, which is typical of contemporary laser diodes. RF transmit power is 200 mW, an average value of microcell base stations. The transmission distance for both the FSO and RF links is 1500 m. (1.5 km). This distance is sufficient to operate the gamut of OSNR required and is at the upper limit of generally reliable FSO operation with low-altitude (100 m.) turbulence and other atmospheric impairments. The values of α = 3.0and β = 2.1represent moderately turbulent conditions.

Due to the high available bandwidth, the FSO channels use OOK modulation (1 bit per symbol) whereas due to limited bandwidth the RF channels use quadrature amplitude modulation (QAM) with two bits per symbol.

A total RF bandwidth of 30 MHz is used. The RF channels use quadrature amplitude modulation (QAM) and direct-sequence spread spectrum (DSSS) with a processing gain (ratio of spread to unspread bandwidth) of Gp = 6. The FSO channels do not use DSSS, therefore Gp = 1.

Table 1. Hybrid channel parameters.

Figure 5 demonstrates a scenario in which the hybrid network experiences degrading optical propagation conditions:

6.1. Initial Condition: Still Air, No Rain

With no turbulence or rain attenuation, BER is less than 5 × 10−4 and outage capacity is greater than 5.01 × 104 Mbps. The channel is assigned a load of 5.01 × 104 Mbps. No loss of data or users occurs under this condition.

6.2. Onset of Rain

BER transitions from the low to the high regime, increasing to 0.20. Outage capacity is now 3.6 × 104 Mbps which is lower than the offered load of 5.01 × 104. The channel experiences an outage since the offered load is greater than the outage capacity under this BER condition (note that the BER scale has been expanded).

6.3. Increasing Turbulence

The onset of turbulence causes BER increase to 0.24. Outage capacity is reduced to 3.3 × 104 Mbps which is still lower than the offered load of 5.01 × 104. The channel outage continues. Applying load shedding as commanded by the optimal PM service results in the following behavior:

6.4. Load Shedding and Correction

BER has increased to 0.24. The PM service observes the increasing BER trend. Prior to allowing the outage capacity to drop below the offered load, the PM service reduces the offered load (by removing users from the channel) from 5.01 × 104 to 2.6 × 104 Mbps corresponding to a maximum BER of 0.29. Since the offered load is now less than the outage capacity at the actual BER (0.24), which is 3.3 × 104 Mbps service of the hybrid channel is restored.

Figure 5. Outage capacity objective function in the hybrid FSO/Ricean channel onset of turbulence.

The feedback dynamics of the traffic balancing and load-shedding algorithms are designed to effect the required adjustment in traffic while maintaining the actual load at an acceptable margin above the outage capacity at the current BER.

Figures 6 and 7 compare the sensitivity of the objective function with that of a measurement based purely on error rate vs. OSNR in the high BER regime. The derivative of both functions is determined as a measure of the sensitivity of the parameter with respect to the independent variable (in the case of the objective function, the derivative of the outage capacity with respect to the BER, and for the BER/OSNR measurement, the derivative of the BER with respect to the OSNR).

The high BER example here is the same as that in the previous section demonstrating the use of the objective function in a degrading environment. To compare sensitivities in a typical example, we calculate the derivative of the objective function (outage capacity) with respect to BER, and the derivative of the BER with respect to OSNR for the hybrid channel with Ricean RF (beamforming).

The first observation made in the high BER regime sensitivity comparison is that the objective function’s sensitivity is greater than that of BER vs. OSNR (corresponding to this high BER range) measurement by a factor of 1300 - 1700 or 31 - 62 dB. The BER vs OSNR slope is essentially constant in this BER regime while the objective function’s slope exhibits an increase with BER. Thresholding based on OSNR/SIR alone often yields less than desirable results since the error rate exhibits a large slope with respect to SNR near the knee of the error rate performance curve. The control system utilizing the objective function is provided with this gain improvement and can thus effect a significantly faster adjustment of

Figure 6. Derivative of objective function, hybrid FSO and ricean channel with beamforming.

Figure 7. Derivative of BER w/r/t OSNR, hybrid FSO/ Ricean channel.

the offered load than one using a BER vs OSNR measurement. A significant observation is that the slope of the BER vs OSNR measurement in the high BER regime is very small, starting with an optical MIMO system of 10 transmitters. For any size system above 10, the response of the BER measurement to changes in OSNR is very low compared to that of the outage capacity.

The objective function shows that outage capacity of the network may be traded off for BER. In applications in which the maximum capacity is the most important factor, a higher error rate may be tolerated in favor of high capacity. The outage capacity objective function allows equally reliable and optimal performance monitoring in both types of applications, high capacity/high BER and reduced capacity/low BER. In many applications BERs in the high BER regime are unacceptably high. The previous example applies to cases in which a high BER may be tolerated.

The low BER regime below 0.02 experiences similar behavior. In the low BER regime it is noted that the objective function’s sensitivity is once again greater than that of BER vs OSNR. The BER vs OSNR slope exhibits a small variation of −2.1 to −2.4 in this range. In this regime the control system is provided with an average 46 dB of gain improvement. The speed of adjustment of the offered load using the objective function is thus improved using the objective function in low BER regime over that of measuring BER vs OSNR alone. As in the high BER case the slope of the BER vs OSNR measurement in the high BER regime is low, starting with an optical MIMO system of 10 transmitters.

7. Conclusions

The sensitivity of the objective function to channel performance degradation is significantly higher than that of the BER measurement as demonstrated by the previous comparisons. The derivative of the BER vs OSNR measurement in the high BER regime shows no change between 0.2 and 0.29 BER, and for much of the high BER regime starting with an optical MIMO system of 10 transmitters. For any size system above 10, there is very little response of the BER measurement to changes in OSNR. The control system that is adjusting the offered load based on a BER measurement can effect very little correction in this case, due to low or zero gain, in this regime for large MIMO arrays. As a result of the low sensitivity of BER upon the SIR/SNR and OSNR, the network manager, using these performance metrics, is unable to offload the traffic from degrading channels prior to failure. In contrast, the objective function provides high sensitivity. The NMS will be able to effect an early correction by offloading the degrading channel to maintain an acceptable margin below the outage capacity before any outage is experienced by the user.

In addition to high sensitivity, the objective function has several major advantages as a performance monitoring parameter over traditional figures of merit including simplicity—it is a function of a single independent variable), ease of measurement—error rate measurement is provided by most optical and RF transmission equipment, cross-domain (FSO and RF) characterization, and intrinsic correction—the objective function continuously provides the adjustment in traffic load required to restore channel operation.

8. Further Research

The objective function has been characterized for other RF fading environments such as Rayleigh and Nakagami-m, Nakagami-n, and Nakagami-c. Research is also conducted to characterize the objective function with the Hata-Nakamura transmission model that is widely used in characterizing performance in urban environments. In the case of Rayleigh and Nakagami environments, the fading distributions associated with the Rayleigh and Nakagami PDFs are analytically determined and the capacity model conditioned upon them—using the method developed for the Ricean case in this study. The HataNakamura model, for which much numerical performance data exists, is currently being incorporated into the network simulation. The simulation, parameterized with the Hata-Nakamura propagation data for the RF channels, will then be operated over the OSNR/SIR gamut to empirically derive the objective function.

9. Acknowledgements

The author thanks Profs. R. Martini, W. Carr, and K. Stamnes for their valuable suggestions in the course of this work.

REFERENCES

- J. Li and M. Uysal, “Optical Wireless Communications: System Model, Capacity, and Coding,” Proceedings of the IEEE Vehicular Technology Conference, Orlando, 6-9 October 2003, pp. 168-172.

- E. Bayaki, R. Schober and R. K. Mallik, “Performance Analysis of Free-Space Optical Systems in GammaGamma Fading,” IEEE Global Telecommunications Conference, (GLOBECOM 2008), New Orleans, 30 November-4 December 2008, pp. 1-6.

- X. Zhu and J. Kahn, “Free-Space Optical Communication through Atmospheric Turbulence Channels,” IEEE Transactions on Communications, Vol. 50, No. 8, 2002, pp. 1293-1300. http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/TCOMM.2002.800829

- W. Gappmair and S. Muhammad, “Error Performance of PPM/Poisson Channels in Turbulent Atmosphere with Gamma-Gamma Distribution,” Electronics Letters, Vol. 43, No. 16, 2007, pp. 880-882. http://dx.doi.org/10.1049/el:20070901

- B. Friedlander and S. Scherzer, “Beamforming vs Transmit Diversity in the Downlink of a Cellular Communications System,” IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology, Vol. 53, No. 4, 2004, pp. 1023-1034. http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/TVT.2004.830980

- R. Martini and E. Whittaker, “Quantum Cascade LaserBased Free Space Optical Communications,” Journal of Optical and Fiber Communications Reports, Vol. 2, No. 4, 2005, pp. 279-292. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10297-005-0052-2

- B. Schmidt, “Optimal Performance Monitoring for a Hybrid Long-Wavelength FSO and Radio Frequency Wireless Network in Fading Channels,” Ph.D. Dissertation, Department of Physics, Stevens Institute of Technology, Hoboken, 2013.

- A. Garcia-Zambrana, C. Castillo-Vazquez and B. Castillo-Vazquez, “On the Capacity of FSO Links over Gamma-Gamma Atmospheric Turbulence Channels Using OOK Signaling,” European Society for Information Processing (EURASIP) Journal on Wireless Communications and Networking, Vol. 2010, 2010, Article ID: 127657. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2010/127657

- A. Farid and S. Hranilovic, “Outage Capacity Optimization for Free-Space Optical Links with Pointing Errors,” IEEE Journal of Lightwave Technology, Vol. 25, No. 7, 2010, pp. 1702-1710. http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/JLT.2007.899174

- A. Farid and S. Hranilovic, “Diversity Gain and Outage Capacity Probability for MIMO Free-Space Optical Links with Misalignment,” IEEE Transactions on Communications, Vol. 60, No. 2, 2012, pp. 1702-1710. http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/TCOMM.2011.121611.110181

- L. Andrews, “Special Functions for Engineers and Applied Mathematicians,” MacMillan, New York, 1985.