Open Journal of Medical Psychology, 2013, 2, 17-24 doi:10.4236/ojmp.2013.24B004 Published Online October 2013 (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ojmp) Body-focused Anxiety in Women: Associations with Internalization of the Thin-ideal, Dieting Frequency, Body Mass Index and Media Effects Aileen Pidgeon, Rachel A. Harker Bond University, Australia Email: apidgeon@bond.edu.au Received July, 2013 ABSTRACT Exposure to media that portrays thin women as ideal and attractive can lead to women internalizing the thin ideal, which results in incorporating societal standards of thinness into belief systems. Internalization of the thin-ideal is asso- ciated with numerous detrimental effects on women, including decreased levels of self-esteem and increased levels of body-focused anxiety, negative emotions and disordered eating. The present study utilized a sample of women (N = 208) aged between 18 and 67 years (M = 29.44, SD = 13.08) to examine the relationship between internalization of the thin- ideal, body-focused anxiety, body mass index (BMI), and dieting frequency. Correlational, regression and mediation analyses conducted on the data showed that internalization of the thin-ideal, BMI and dieting frequency significantly contributed to body-focused anxiety in women. In addition, body-focused anxiety fully mediated the relationship be- tween internalization of the thin-ideal and dieting frequency among women. BMI did not moderate the relationship be- tween internalization of the thin-ideal and body-focused, indicating that women who internalize the thin-ideal are less vulnerable to dieting unless experiencing body-focused anxiety. The results of the current study enhance our under- standing of the relationship between internalization of the thin-ideal, body-focused anxiety, BMI, and dieting frequency among women. Clinical implications will be discussed. Keywords: Body-focused Anxiety; Internalization of the Thin-ideal; BMI; Dieting 1. Introduction The thin-ideal relates to current societal standards of fe- male beauty, in particular the female body, portrayed by the media as a level of thinness that is impossible for most women to achieve [1].The standards of appearance and beauty portrayed by the media, which includes the consistent portrayal of women of an unattainable stature and portraying underweight female models as ‘normal’, contributes to poor body image amongst women. Inter- nalization of societal standards includes both the accep- tance and endorsement of the messages sent by the media that thin women are attractive [2]. The term internaliza- tion of the thin-ideal is the degree that women cogni- tively adopt socially defined beliefs of attractiveness, which results in women engaging in behaviors, such as chronic dieting, to achieve a body in line with the thin-ideal [3,4]. Some women incorporate the values of the thin-ideal such as, ‘women must be thin to be consid- ered attractive’, which become the guiding principles in their lives [5]. Reinforcement and perpetuation of the thin-ideal is achieved through socialization agents such as the mass media encouraging women to diet and lose weight exemplified in the glorification of ultra-thin mod- els [4]. Furthermore, the mass media targets women by promoting new diets, exercise regimens, and beauty treatments to rectify and conceal flaws in their bodies to achieve attractiveness and the thin-ideal [6]. The factors examined in this paper are defined as fol- lows. Body-focused anxiety, which is analogous to body dissatisfaction, refers to the extent in which a woman feels at unease about her body and physical appearance [7, 8]. Dieting frequency is the frequency women diet to lose weight to ease the anxiety and dissatisfaction felt about their bodies. Positive expectancies associated with being thin refers to women adopting the belief that the associated benefits of being thin are increased success, happiness and popularity [9,10]. Women who perceive the thin-ideal as the norm and believe it is attainable with effort and sacrifice tend to selectively expose themselves to media content that is congruent with this belief system [11, 12]. Exposure to media that portray thin women as ideal women can result in women internalizing the thin-ideal, developing body dissatisfaction and chronic dieting [13, 14]. Over the past Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OJMP  A. PIDGEON, R. A. HARKER 18 decades, the average weight of women has increased [15], while women portrayed in the media, particularly models, have become increasingly thinner [16]. The gap between the typical thin ideal body of women portrayed by the media and the size of the average woman’s body haswi- dened [17] promoting the notion that thin models are more attractive than the realistically sized women. Re- cent research indicates that it is the thinness of the mod- els, rather than their attractiveness, that leads to increased body-image concerns [18, 19]. These studies controlled for attractiveness and found that exposure to thin size 8 models, but not to size 14 models, resulted in increased body-focused anxiety. The thin-ideal internalization directly cultivates body- focused anxiety and dissatisfaction because the thin-ideal portrayed by the media is unattainable for most women [20]. Body dissatisfaction is identified as women having negative thoughts and feelings about their body [7, 8], such as believing parts of their body are not thin enough. Body dissatisfaction is proposed to arise from socio cul- tural pressures from the media to conform to the thin-ideal and physical deviation from the ideal espoused for women [21]. Body dissatisfaction can result from heightened internalization of the thin-ideal and the belief that attaining the thin-ideal will result in a multitude of benefits [7, 22, 23]. Additionally, dieting is a behavioral indicator of body-focused anxiety and dissatisfaction [7]. How the thin-ideal standard of appearance and beauty for women portrayed in the media influences the preva- lent phenomenon of body dissatisfaction among women is explained by sociocultural theory and self-discrepancy theory. Sociocultural theory postulates there is a link between pressures from social sources, such as the media, and body dissatisfaction. This theory attains there is per- vasive societal pressure, from the media, on women to conform to the thin-ideal and that this pressure has re- sulted in a culture of thinness in Western society [24]. The mass media is identified as the most pervasive and powerful social influence [25]. The sociocultural pres- sures by the media on women to be thin are associated with body dissatisfaction among women [26]. Self-discrepancy theory refers to the beliefs held by women about who they are (actual self), who they would like to be (ideal self) and who they ought to be (ought self)[27]. When a discrepancy exists between the actual and ideal self, this is called an ideal discrepancy [27]. Women who report experiencing an ideal discrepancy between their actual body size and body mass index (BMI), and their ideal body size report low body satis- faction, self-criticism, emotional distress and engage in self-regulatory behaviors, such as dieting, to mitigate the distress and moderate the incongruity [28-30]. The media is a key player in propagating the thin-ideal, resulting in women feeling dissatisfied with their bodies [31]. In par- ticular, the media communicates expectations pertaining to the benefits of conforming to the thin-ideal (“thin is good”), from which women develop positive expectan- cies and belief relative to thinness and dieting (e.g., in- creased success, confidence, respect and attractiveness) [10,32]. These expectations play a key role in the propa- gation of the thin-ideal, with advertisements (ranging from beer to make-up commercials) consistently using “successful” and attractive women who look like the significantly underweight models also seen in the fashion magazines [31]. As a result, society is inundated with the message that thin women are successful and attractive, and women begin to internalize expectancies associated with conforming to the thin-ideal. Whilst the media em- phasizes and glorifies thinness, there is a powerful socie- tal stigma against obesity; to the extent society associates obese individuals with personality traits such as laziness, gluttony and lack of self-control [11, 33]. A meta-analytic review revealed the negative effect on women being exposed to the thin-ideal as portrayed in the mass media [3]. Results found that for body dissatis- faction there was a small to moderate mean effect size (d) of -0.28 across 90 independent effect sizes, indicating a relationship between exposure to the ultra-thin images by the mass media, analogous to the exemplar models in the media and body dissatisfaction in women [3]. In addition, results found a relationship between the media and inter- nalization of the thin-ideal, with over 23 independent effect sizes for internalization of the thin-ideal having a small to moderate mean effect size (d) of -0.39 [3]. These results support the socio cultural perspective that the me- dia propagates a thin-ideal for women which contributes to body dissatisfaction among women [25].In addition, internalization of the thin-ideal has been shown to sig- nificantly influence the relationship between body dis- satisfaction and perceived media pressure in young women aged between 10-13 years [34]. BMI is a significant moderator of internalization of the thin-ideal. Research indicates that women with high lev- els of internalization of the thin-ideal and high BMI’s, also report significantly greater levels of body dissatis- faction [35]. Previous research suggests that being over- weight does not result in body-focuses anxiety and dis- satisfaction unless the thin-ideal has been internalized [24]. 1.1. The Current Study The current study seeks to further our understanding of the effect of the media on women by examining the di- rectional links between internalization of the thin-ideal, body-focused anxiety and dieting frequency within a testable mediation model shown in Figure 1. Figure 1 shows the hypothesized pathway between internalization of the thin-ideal and body-focused anxiety (pathway a). Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OJMP  A. PIDGEON, R. A. HARKER Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OJMP 19 mediate the relationship between internalisation of the thin-ideal and dieting frequency. Previous research has demonstrated internalization of the thin-ideal directly fosters body-focused anxiety because it is unattainable for most women [21]. The predictive pathway between body-focused anxiety and dieting fre- quency (pathway b) was formulated on the proposition that individuals who experience body-focused anxiety are likely to diet as it is a common belief dieting is an effective weight control technique [4]. Based on previous research that shows there is an association between body dissatisfaction and increased dieting frequency, and due to the fact that body-focused anxiety is positively related to internalization of the thin-ideal, it was predicted that internalization would indirectly predict dieting frequency via body-focused anxiety (pathway a and b). The direct effect between internalization and dieting frequency (c’) must be significantly reduced from the total effect (c), before it can be reliably suggested that mediation exists [36]. Hypothesis 4 statedBMI would moderate the relation- ship between internalization of the thin-ideal and body- focused anxiety. 2. Method The sample consisted of208women aged between 18 and 67 years (Mage= 29.44, SD = 13.08). 2.1. Measures Body mass was measured with BMI collected via the demographics. BMI = Weight (kg) / Height2 (m2), based on self-report data. Self-reported dieting frequency was collected via the demographics. Sociocultural Attitudes towards Appearance Scale-3 (SATAQ-3) is a 30-item self-report questionnaire that provides a reliable measure of the sociocultural influence of multiple dimensions of media on female body image [5]. Items were summed to produce a total score, and higher scores indicated increased internalization of so- cially presented views regarding the importance of at- tractiveness in society [37]. The current study used the internalization-general subscale, which assesses inter- nalization and acceptance of societal standards of the thin-ideal. The current study builds on previous research by ex- amining the relationship between body-focused anxieties, internalization of the thin-ideal, BMI, dieting frequency, desirability and positive expectances. In addition, the current study will examine the moderating effect of BMI between internalization and body-focused anxiety among women. 1.2. Hypotheses Physical Appearance Trait and State Anxiety Scale (PASTAS [Trait Subscale]) was used to measure body- focused anxiety for eight weight-related (e.g., thighs and buttocks) body sites [38]. Scores were summed to reveal a weight-related anxiety total, with higher scores indi- cating higher levels of body-related, appearance anxiety. The following hypotheses were formulated from past research and literature reviewed above. Hypothesis 1 stated internalization of the thin-ideal, body-focused anxiety, BMI, dieting frequency, desirabil- ity and positive expectancies associated with being thin would be significantly positively related. Media Attitudes Questionnaire (MAQ) is a 22-item measure used to assess media skepticism [9]. Higher scores indicate lower levels of media skepticism and greater endorsement of the statements. The current study used the desirability and positive expectancies associated with being thin subscales. Hypothesis 2 stated BMI, dieting frequency, internali- zation of the thin-ideal, desirability and positive expec- tancies associated with being thin would significantly predict body-focused anxiety. Hypothesis 3 stated body-focused anxiety would fully Body-Focused Anxiety Internalization Dieting Frequency a c’ (c) b Figure 1. Hypothesized mediation model of the relations between body-focused anxiety, internalization of the thin-ideal and dieting frequency.  A. PIDGEON, R. A. HARKER 20 2.2. Design A cross-sectional, correlational design using bivariate correlation, standard multiple regression, mediated re- gression and moderated regression analyses was used. The standard multiple regressions were performed using the predictor variable body-focused anxiety and criterion variables BMI, dieting frequency, internalization of the thin-ideal, desirability, and positive expectances. The mediated regression was performed using body-focused anxiety as the mediator, internalization of the thin-ideal as the predictor and dieting frequency as the criterion variable. A moderated regression was conducted using BMI as the moderator, internalization of the thin-ideal as the predictor and body-focused anxiety as the criterion variable. 3. Results 3.1. Correlational Analysis Table 1 show that BMI was significantly positively cor- related with dieting frequency and body-focused anxiety. Dieting frequency was significantly positively correlated with internalisation, body-focused anxiety and positive expectancies and contrary to predictions did not signifi- cantly correlate with desirability. Internalisation was sig- nificantly positively correlated with body-focused anxi- ety, desirability and positive expectancies. Body- focused anxiety was significantly positively correlated with de- sirability and positive expectancies. In addition, desir- ability and positive expectancies were significantly posi- tively correlated. 3.2. Main Analyses Standard Multiple Regression Analysis. Body-focused anxiety was regressed onto BMI, dieting frequency, in- ternalization of the thin-ideal, desirability, and positive expectances. As predicted, the model accounted for a significant amount of variance in body-focused anxiety, R2 = 0.50, adjusted R2 = 49, F (5, 202) = 40.18, p < 0.001. As indicated by the R2 value of .50, 50% of the variance in body-focused anxiety is predicted by BMI, dieting frequency, internalization of the thin-ideal, desirability, and positive expectances. The regression coefficients for BMI, dieting frequency and internalization of the thin- ideal differed significantly from zero. However, in con- trast to prediction, the regression coefficients for desir- ability and positive expectancies did not differ signifi- cantly from zero. Therefore, desirability and positive expectancies were excluded from all further analyses. BMI contributed 11.16% unique variance to body-focused anxiety, whilst dieting frequency contributed 6.55%, and internalization of the thin-ideal contributed 6.81% unique variance. Thus, 24.12% of the variance in body-focused anxiety can be attributed to shared variability amongst the predictor variables; dieting frequency, BMI, inter- nalization of the thin-ideal, desirability and positive ex- pectancies. Mediated Analysis.Linear and hierarchical multiple regression procedures and a Sobel test [39] were per- formed to test the third hypothesis. In the simple regres- sion analysis internalisation accounted for a significant amount of variance in body-focused anxiety, R2 = 0.25, Adjusted R2 = .25, F(1, 206) = 68.17, p < .001. Moreover, the coefficient for internalisation was significant β = .50, p < 0.001. A hierarchical multiple regression analysis was conducted predicting dieting frequency. Internaliza- tion was entered on Step 1 and body-focused anxiety on Step 2 of the regression equation. The results of the hier- archical multiple regression equation are summarized in Table 2. As shown in Table 2, internalization accounted for 10.9% of the variance in dieting frequency at Step 1, R2change = 0.11, Fchange = (1, 206) = 25.18, p < 0.001, addi- tionally the coefficient for internalization was significant, β = .33, p < 0.001. Table 2 shows that at Step 2, body-fo- cused anxiety explained a significant increment in the variance accounted for in dieting frequency, R2change = 0.15, Fchange = (1, 205) = 40.87, p < 0.001. The coeffi- cient for body-focused anxiety was significant at Step 2, β = 0.44, p< 0.001. When body-focused anxiety was en- tered on Step 2, the coefficient for internalization mark- edly decreased to β = 0.11 and was not significant (p = 0.119), these findings are in support of hypothesis three. A Sobel test [39] was conducted to establish if the de- crease in the coefficient for internalization was significant. Table 1. Means, standard deviations and Pear son correlation coefficients among the variables. Measure 1 2 3 4 5 6 M SD 1. Body Mass Index .18** -.09 .36*** -.03 -.01 23.53 4.55 2. Dieting Frequency .33*** .50*** .13 .29*** 2.61 1.25 3. Internalization .50*** .47*** .68*** 27.47 9.52 4. Body-Focused Anxiety .20*** .44*** 16.74 7.31 5. Desirability .48*** 12.52 2.72 6. Positive Expectancies 12.71 5.87 *p< 0.05. **p< 0.01. ***p< 0.001. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OJMP  A. PIDGEON, R. A. HARKER 21 Table 2. Hierarchical multiple regression analysis predicting dieting frequency from internalization of the thin-ideal and body-focused anxiety (N = 208). Predictor ∆R2 β B SE B 95% CI for B Step 1 .11*** Constant 2.61 0.08 [2.45, 2.77] Internalization .33*** 0.04 0.01 [.03, .06] Step 2 .15*** Constant 2.61 0.08 [2.46, 2.76] Internalization .11 0.01 0.01 [-.00, .03] Body-Focused Anxiety .44*** 0.08 0.01 [.05, .10] Total R2 = .26*** Note:. CI = Confidence Interval; *p< 0.05. **p< 0.01. ***p< 0.001. Sobel’s test indicated perfect mediation, as the decrease in the coefficient was significant (z = 5.04, p < 0.001). Moderated Analysis. A moderated regression analy- sis was performed to examine the fourth hypothesis. A hierarchical multiple regression analysis was performed to examine the variance accounted for by internalization of the thin-ideal, BMI and the interaction term (Inter- nalization X BMI) when predicting body-focused anxiety. Internalization and BMI were entered at Step 1, and the interaction term (Internalization X BMI) was entered at Step 2. However, entering the interaction term (Inter- nalization X BMI) did not add significantly to the ex- plained variance after controlling for the main effects of internalization of the thin-ideal and BMI on body-focused anxiety. BMI did not moderate the rela- tionship between internalization and dieting frequency and did not support the fourth hypothesis. 4. Discussions The current study examined the relationships between body-focused anxiety, internalization of the thin-ideal, BMI, dieting frequency, desirability and positive expec- tancies among women. Results provided partial support for hypothesis one, with all variables significantly posi- tively correlated with the exception of the correlations between BMI and internalization of the thin-ideal, BMI and desirability and, BMI and positive expectancies. These results were contrary to the prediction that BMI- would have a significant relationship with all three vari- ables. In addition, converse to expectations the results indicated there was a non-significant correlation between dieting frequency and desirability. Post hoc interpretation suggests the negative correla- tion between BMI and internalization of the thin-ideal could be explained by the fact that those women with a high BMI may reject societal norms and not have the desire to conform to the thin-ideal. This result supports Harrison’s [11] argument that women selectively expose themselves to media content that conforms to their exist- ing worldview. Women who have a greater BMI and have rejected the thin-ideal might selectively expose themselves to media content that conforms to their per- sonal worldview (e.g., average to overweight models). The result that dieting frequency was not significantly correlated with desirability was unexpected as it was anticipated women who desire to look like the thin mod- els portrayed in the media would have elevated dieting frequencies in order to achieve the thin-ideal. It is possi- ble that the women in the current study who desire to look like the thin exemplar model portrayed by the me- diamay use healthy means to lose or maintain weight, such as exercise and balanced diets. Hypothesis two was partially supported. Whilst BMI, dieting frequency and internalization significantly con- tributed to body-focused anxiety, desirability and posi- tive expectancies did not. Despite desirability and posi- tive expectancies having moderate to strong bivariate correlations with body-focused anxiety, they did not play a significant unique role in the extent to which women experience body-focused anxiety. The finding that BMI played a significant unique role in body-focused anxiety was consistent with previous research that found that being overweight is a major determinant of body dissat- isfaction [24]. The result that dieting frequency significantly contrib- utes to unique variance to body-focused anxiety was ex- pected. This finding supports previous research that in- dicates body-focused anxiety promotes dieting [10]. The results of Stice’s [10] study, in conjunction with the re- sults from the current study demonstrate the relationship between dieting frequency and body-focused anxiety may be cyclical. Specifically, body-focused anxiety promotes dieting, but despite dieting, many women fail to achieve the thin-ideal as it is unattainable for most women, which leads to dieting promoting body-focused anxiety [6]. In addition, the strong positive correlation between di- eting and body-focused anxiety provides support for self-discrepancy theory. Women who experience a dis- crepancy between their actual and ideal self tend to en- gage in behaviors to try and “fix” the discrepancy [27]. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OJMP  A. PIDGEON, R. A. HARKER 22 As such, the relationship between dieting and body-focused anxiety can be explained in terms of dis- satisfaction, which can results from a discrepancy be- tween the actual and ideal self, and attempts to amend the discrepancy involve dieting. In support of hypothesis three, the results indicated body-focused anxiety fully mediated the relationship between internalization of the thin-ideal and dieting fre- quency. Women who internalize the thin-ideal do not necessarily diet unless they experience body-focused anxiety. These findings highlight the importance of de- veloping interventions aimed at preventing and decreas- ing body-focused anxiety in women of all ages. Body- focused anxiety can lead to dieting, and can be a precur- sor to disordered eating. Although BMI was significantly correlated with body-focused anxiety and contributed unique variance to body-focused anxiety, the final hypothesis was not sup- ported by the results. These findings are consistent with past research [34].Internalization of the thin-ideal and BMI significantly predicted body-focused anxiety indi- vidually, but the interaction between the two variables did not predict body-focused anxiety. The strong associa- tion between BMI and body-focused anxiety in the cur- rent study demonstrates that women with a high BMI can also experience body-focused anxiety and not internalize the thin-ideal. The result may be explained in terms of the stigma society places on overweight women and obe- sity [33]. Being thin is associated with a number of bene- fits [22] and being overweight is not [11,33].The results are contrary to arguments that theoretically having a greater BMI would only produce body-focused anxiety if the thin-ideal had been internalized[24]. The results of the current study demonstrate that in- ternalization of the thin-ideal; BMI and dieting are con- tributing factors to body-focused anxiety. Adapted from Blowers et al. [34], Figure 2 proposes an updated model on the relationship between these variables that includes both psychological (e.g., internalization) and physical features (e.g., BMI). The potential cyclical relationship between dieting and body-focused anxiety is shown in Figure 2. Some limitations of the current study warrant consid- eration, including the cross-sectional, correlational de- sign of the current study limits the interpretation from the results, as no causal inferences can be made. Therefore, it is recommended that future research investigate causal priority by experimentally manipulating variables of in- terest. 5. Conclusions The relationship between internalization of the thin-ideal and body-focused anxiety was demonstrated in the current study among women across a broad range ages (18-67 Figure 2. Modified model of the relationships between body-focused anxiety, internalization of the thin-ideal, diet- ing frequency and BM I. years). These further our understanding of the relation- ships between body-focused anxiety, internalization of the thin-ideal, BMI and dieting. These results provide evidence of a need for change, as it seems that women across a broad age range may be manipulating their bod- ies through dieting to achieve the thin-ideal and body- focused anxiety. In conclusion, the current study high- lights the importance of addressing body-focused anxiety in women across the adult life span by developing multi- focus interventions aimed at preventing and decreasing body-focused anxiety and internalization of the thin- ideal. REFERENCES [1] M. Tiggemann, “Body Image across the Adult Life Span: Stability and Change,” Body Image, Vol. 1, 2004, pp. 29-41. doi:10.1016/S1740-1445(03)00002-0 [2] L. J. Heinberg, J. K. Thompson and S. Stormer, “Devel- opment and Validation of the Sociocultural Attitudes to- wards Appearance Questionnaire,” Journal of Eating Dis- orders, Vol. 17, 1995, pp. 81-89. doi:10.1002/1098-108X(199501)17:1<81::AID-EAT2260 170111>3.0.CO;2-Y [3] S. Grabe, L. M. Ward and J. S. Hyde, “The Role of the Media in Body Image Concerns among Women: A meta-analysis of Experimental and Correlational Studies,” Psychological Bulletin, Vol. 134, 2008, pp. 460-476. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.134.3.460 [4] J. K. Thompson and E. Stice, “Thin-ideal Internalization: Mounting Evidence for a New Risk Factor for Body-image Disturbance and Eating Pathology,” Current Directions in Psychological Science, Vol. 10, 2001, pp. 181-183. doi:10.1111/1467-8721.00144 [5] J. K. Thompson, P. van den Berg, M. Roehrig, A. S. Guarda and L. J. Heinberg, “The Sociocultural Attitudes towards Appearance Scale-3 (SATAQ-3): Development and Validation,” International Journal of Eating Disor- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OJMP  A. PIDGEON, R. A. HARKER 23 ders, Vol. 35, 2004, pp. 293-304. doi:10.1002/eat.10257 [6] J. Rodin, L. Silberstein and R. Striegel-Moore, “Women and Weight: A Normative Discontent,” In: Sonderegger, T.B., Ed., Nebraska symposium on motivation: Vol. 32. Psychology and gender, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, 1984, pp. 267-307. [7] S. Grogan, “Body image: Understandin g Body Dissati sfac- tion in Men, Women, and Children (2nd Ed.),” Routledge, London, 2008. [8] T.A. Myers and J. H. Crowther, “Sociocultural Pressures, Thin-ideal Internalization, Self-objectification, and Body Dissatisfaction: Could Feminist Beliefs be a Moderating Factor?” Body Image, Vol. 4, 2007, pp. 296-208. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2007.04.001 [9] L. M. Irving, J. DuPen and S. Berel, “A Media Literacy Program for High School Females,” Eating Disorders, Vol. 6, 1998, pp.119-131. doi:10.1080/10640269808251248 [10] E. Stice, “A Prospective Test of the Dual Pathway Model of Bulimic Pathology: Mediating Effects of Dieting and Negative Affect,” Journal of Abnormal Psychology, Vol. 110, 2001, pp.124-135. doi:10.1037//0021-843X.110.1.124 [11] K. Harrison, “The Body Electric: Thin-ideal Media and Eating Disorders in Adolescents,” Journal of Communi- cation, Vol. 50, 2000, pp. 119-143. doi:10.1093/joc/50.3.119 [12] J. Kilbourne, “Can’t Buy My Love,” Simon &Schuste, New York, 1999. [13] P. G. Krones, E. Stice, C. Batres and K. Orjada, “In Vivo Social Comparison to a Thin-ideal Peer Promotes Body Dissatisfaction: A Randomized Experiment,” Interna- tional Journal of Eating Disorders, Vol. 38, 2005, pp. 134-142. doi:10.1002/eat.20171 [14] E. Stice, “Sociocultural Influences on Body Image and Eating Disturbance,” In: Fairburn, C.G and Bronwell, K.D., Eds., Eating Disorders and Obesity: A comprehen- sive Handbook, The Guildford Press, New York, 2002, pp. 103-107. [15] K. M. Flegal, M. D. Carroll, C. L. Ogden and C. L. John- son, “Prevalence and Trends in Obesity among US Adults, 1999-2000,” Journal of the American Medical Associa- tion, Vol. 288, 2002, pp. 1723-1727. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.14.1723 [16] N. Hawkins, P. S. Richards, H. Granley and D. M. Stein, “The Impact of Exposure to the Thin-ideal Media Image on Women,” Eating Disorders, Vol. 12, 2004, pp. 35-50. doi:10.1080/10640260490267751 [17] B. L. Spitzer, K. A. Henderson and M. T. Zivian, “Gender Differences in Population Versus Media Body Sizes: A comparison over Four Decades,” Sex Roles, Vol. 40, 1999, pp. 545-565. doi:10.1023/A:1018836029738 [18] H. Dittmar and S. Howard, “Professional Hazards? The Impact of Model’s Body Size on Advertising Effective- ness and Women’s Body-focused Anxiety in Professions that Do and Do not Emphasize the Cultural Ideal of Thin- ness,” British Journal of Social Psychology, Vol. 43, 2004, pp. 1-33. doi:org/10.1348/0144666042565407 [19] E. Halliwell and H. Dittmar, “Does Size Matter? The Impact of Model’s Body Size on Women’s Body-focused Anxiety and Advertising Effectiveness,” Journal of So- cial and Clinical Psychology, Vol. 23, No. 1, 2004, pp. 104-122. doi:10.1521/jscp.23.1.104.26989 [20] R. D. Peterson, S. Tantleff-Dunn and J. S. Bedwell, “The Effects of Exposure to Feminist Ideology on Women’s Body Image,” Body Image, Vol. 3, 2006, pp. 237-246. doi:org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2006.05.004 [21] J. K. Thompson, L. J. Heinberg, M. Altabe and S. Tantleff-Dunn, “Exacting Beauty: Theory, Assessment, and Treatment of Body Image Disturbance,” American Psychological Association, Washington, 1999. [22] P. C. Evans, “If Only I Were Thin like Her, maybe I could be Happy like Her: The Self-implications of Asso- ciating a Thin Female Ideal with Life Success,” Psycho- logical of Women Quarterly, Vol. 27, 2003, pp. 209-214. doi:10.1111/1471-6402.00100 [23] E. Stice and S. K. Bearman, “Body-image and Eating Disturbances Prospectively Predict Increases in Depres- sive Symptoms in Adolescent Girls: A growth curve analysis,” Developmental Psychology, Vol. 37, 2001, pp. 597-607. doi:10.1037//0012-1649.37.5.597 [24] E. Stice, “Review of the Evidence for a Sociocultural Model of Bulimia Nervosa and an Exploration of the Mechanisms of Action,” Clinical Psychology Review, Vol. 14, 1994, pp. 633-661. doi:10.1016/0272-7358(94)90002-7 [25] L. M. Groesz, M. P. Levine and S. K. Murnen, “The Ef- fect of Experimental Presentation of Thin Media Images on Body Satisfaction: A Meta-analytic Review,” Interna- tional Journal of Eating Disorders, Vol. 31, 2002, pp. 1-16. doi:10.1002/eat.10005 [26] W. Stice and H. E. Shaw, “Role of Body Dissatisfaction in the Onset and Maintenance of Eating Pathology.A Syn- thesis of Research Findings,” Journal of Psychosomatic Research, Vol. 53, 2002, pp. 985-993. doi:10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00488-9 [27] K. Harrison, “Ourselves, our bodies: Thin-ideal media, self-discrepancies, and eating disorder symptomatology in adolescents,” Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, Vol. 20, 2001, pp.289-323. doi:10.1521/jscp.20.3.289.22303 [28] H. Dittmar, E. Halliwell and E. Stirling, “Understand the Impact of Thin Media Models on Women’s Body-focused Affect: The Roles of Thin-ideal Internalization and Weight- related Self-discrepancy Activation in Experi- mental Exposure Effects,” Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, Vol. 28, 2009, pp. 43-72. doi:10.1521/jscp.2009.28.1.43 [29] E. Halliwell and H. Dittmar, “Associations between Ap- pearance-related Self-discrepancies and Young Women’s and Men’s Affect, Body Dissatisfaction, and Emotional Eating: A Comparison of Fixed-item and Participant-gen- erated Self-discrepancies,” Personality and Social Psy- chology Bulletin, Vol. 32, 2006, pp. 447-458. doi:10.1177/0146167205284005 [30] L. J. Heinberg, “Theories of Body Image Disturbance: Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OJMP  A. PIDGEON, R. A. HARKER Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OJMP 24 Perceptual, Developmental, and Sociocultural Factors,” In: Thompson, J. K. and Smolak, L., Eds., “Body Image, Eat- ing Disorders, and Obesity in Youth: Assessment, pre- vention, and Treatment,” American Psychological Asso- ciation, Washington, 2001, pp. 27-47. [31] P. A. Klaczynski, K. W. Goold and J. J. Mudry, “Culture, Obesity Stereotypes, Self-esteem, and the “thin ideal”: A Social Identity Perspective,” Journal of Youth and Ado- lescence, Vol. 33, 2004, pp. 307-317. doi:10.1023/B:JOYO.0000032639.71472.19 [32] L. A. Hohlstein, G. T. Smith and J. G. Atlas, “An Appli- cation of Expectancy Theory to Eating Disorders: Devel- opment and Validation of Measures of Eating and Dieting Expectances,” Psychological Assessment, Vol. 10, 1998, pp. 49-58. doi:10.1037//1040-3590.10.1.49 [33] M. B. Schwartz and K. D. Brownell, “Obesity and body image,” In: Cash, T.F. and Pruzinsky, T., Eds., Body im- age: A Handbook of Theory, Research, and Clinical Practice, The Guildford Press, New York, 2002, pp. 200-209. [34] L. C. Blowers, N. J. Loxton, M. Grady-Flesser, S. Oc- chipinti and S. Dawe, “The Relationship between So- ciocultural Pressure to be Thin and Body Dissatisfaction in Preadolescent Girls,” Eating Behaviors, Vol. 4, 2003, pp. 229-244. doi:10.1016/S1471-0153(03)00018-7 [35] K. G. Low, S. Charanasomboon, C. Brown, G. Hiltunen, K. Long, K. Reinhalter and H. Jones, “Internalization of the Thin Ideal, Weight and Body Image Concerns,” So- cial Behavior and Personality, Vol. 31, 2003, pp. 81-90. doi:10.2224/sbp.2003.31.1.81 [36] K. J. Preacher and A. F. Hayes, “SPSS and SAS Proce- dures for Estimating Indirect Effects in Simple Mediation Models,” Behaviour Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, Vol. 36, 2004, pp. 717-731. doi:10.3758/BF03206553 [37] G. Tsiantas and R. M. King, “Similarities in Body Image in Sisters: The Role of Sociocultural Internalization and Social Comparison,” Eating Disorders, Vol. 9, 2001, pp. 141-158. doi:10.1080/10640260127717 [38] D. L. Reed, J. K. Thompson, M. T. Brannick and W. P. Sacco, “Development and Validation of the Physical Ap- pearance State and Trait Anxiety Scale (PAS- TAS),”Journal of Anxiety Disorders, Vol. 5, 1991, pp. 323-332. doi:10.1016/0887-6185(91)90032-O [39] K. J. Preacher and G. J. Leonardelli, “Calculation for the Sobel Test: An Interactive Calculation Tool for Mediation Tests [Online software],” 2010. http://www.people.ku.edu/~preacher/sobel/sobel.htm

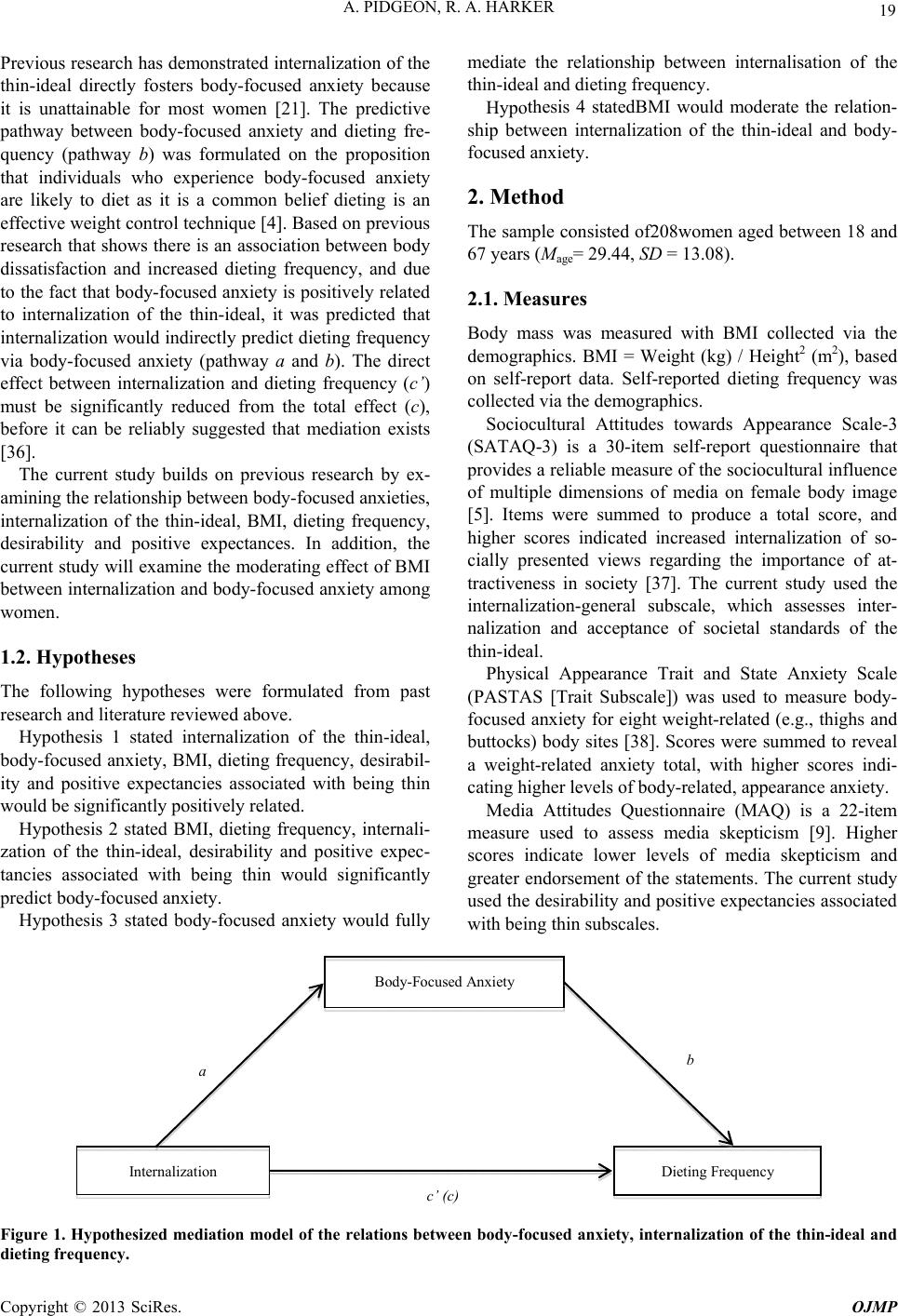

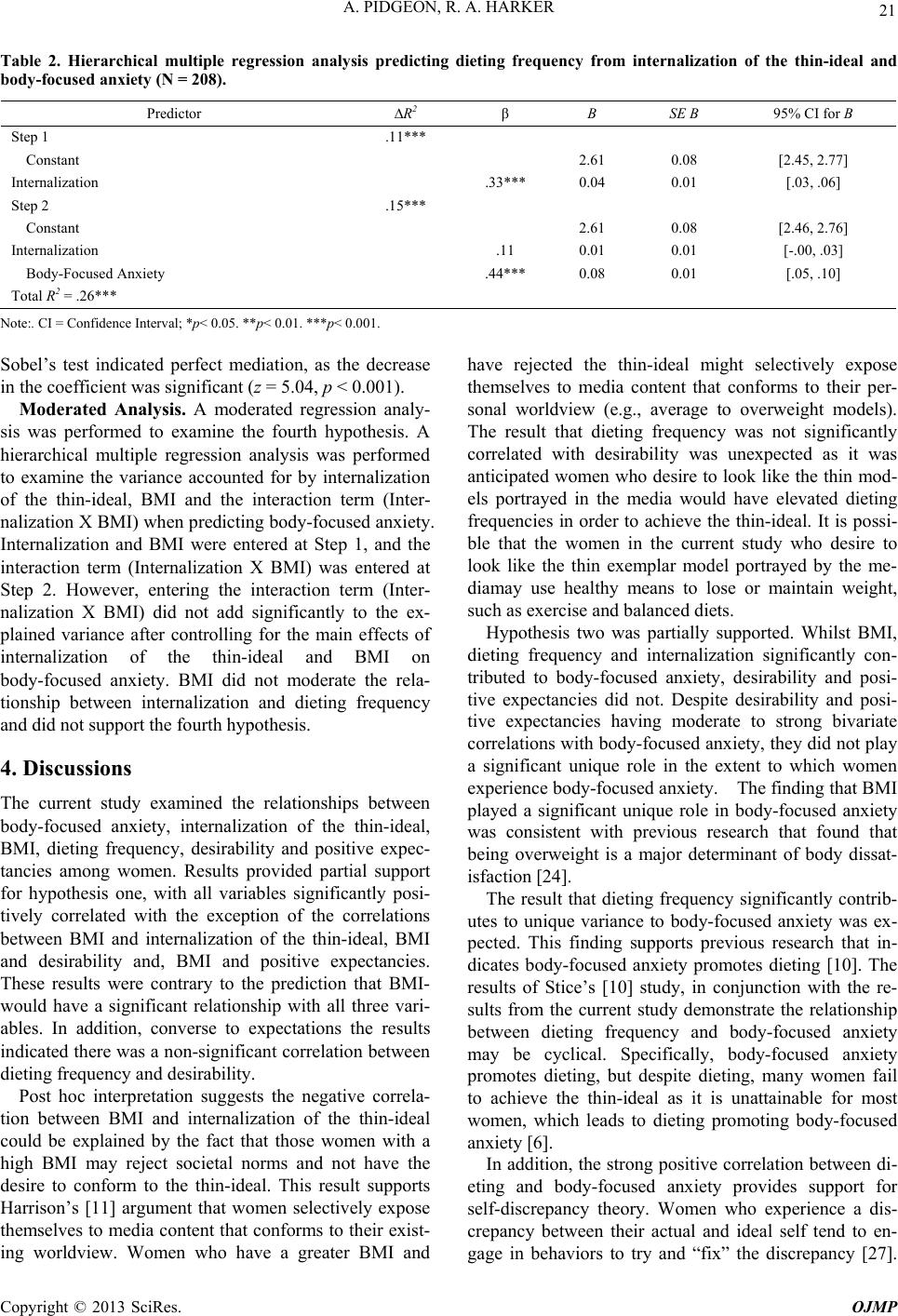

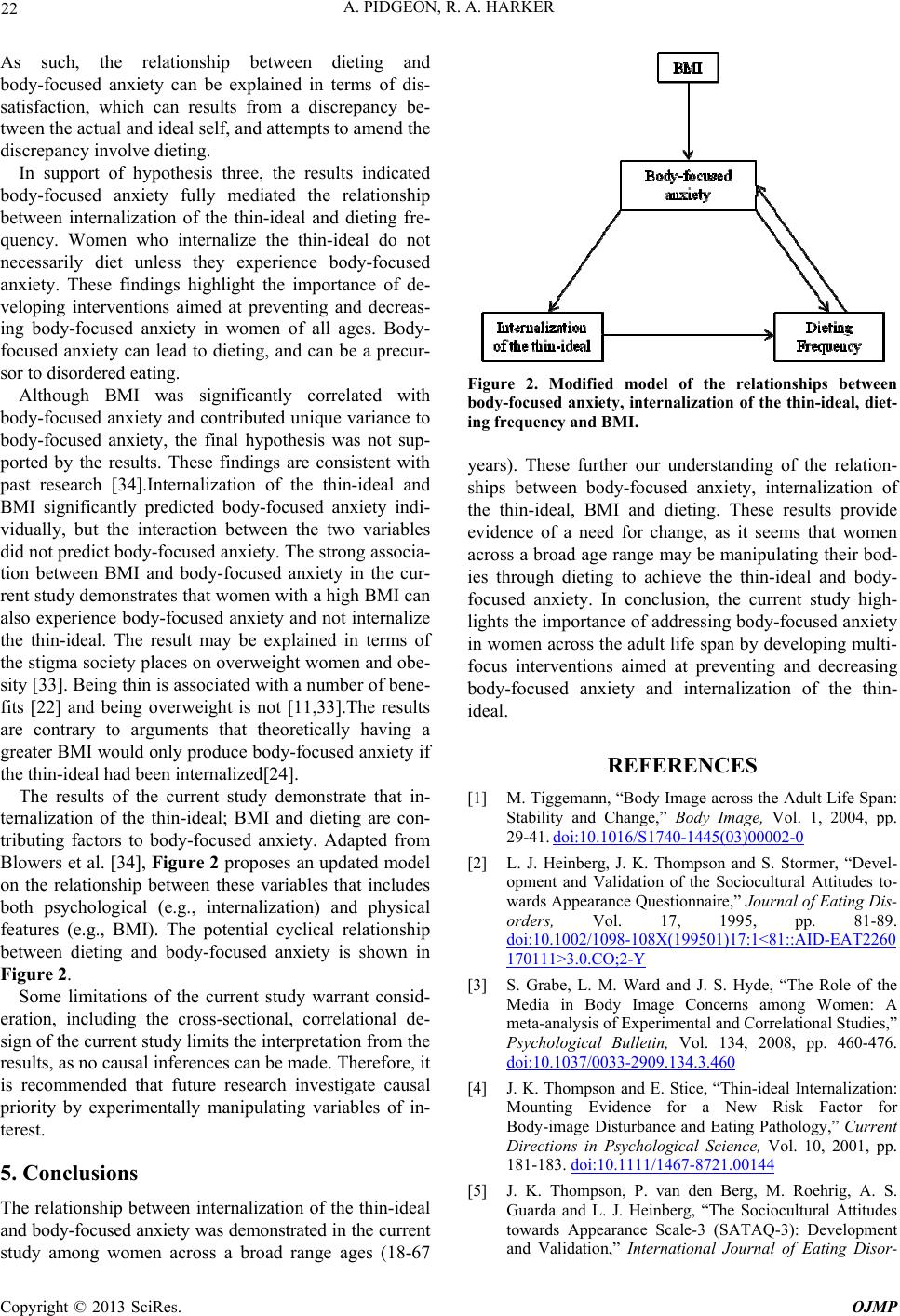

|