Creative Education 2013. Vol.4, No.9, 29-34 Published Online Septe mber 201 3 in SciRes (http ://www.scirp.org/journal/ce) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ce.2013.49B007 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. Application of Form-Focused Instruction in English Pronunciation: Examples from Mandarin Learners Yizhou Lan1, Mengjie Wu2 1Department of Chinese, Translation and Linguistics, City University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, C hina 2Department of the Chinese Language, Beijing Language and Culture University, Beijing, China Email: eejoe.lan@gmail.com, woobluedream@126.com Received June 2013 Training L2 learners’ pronunciation by using a controlled perception procedure has long been the main- stream of L2 speech pedagogy research. However, endeavors have also been done to explore more com- municative teaching methods. The current study presents a paradigm that tests both communicative teaching methods’ renderings of pronunciation pedagogy and a form-focused instruction which is less used in pronunciation pedagogy. The authors introduced a focus-on-form method to pronunciation teach- ing by giving participants information about the speech articulators to help five Mandarin-speaking stu- dents to improve the accuracy in production of English /r/. For the sake of contrasting, another group of five students received communicative training for the same amount of time. Stimuli words for both groups in both pre-test and post-test were embedded in a discourse for participants to read aloud. Produc- tions were recorded and went through both acoustic analysis and native speaker perception for the mea- surement of nativeness. Results showed that the focus-on form method is more effective at least in the presented participants to improve segmental pronunciation performance. Keywords: Pronunciation Pedagogy; Second Language Speech Production; Communicative Language Teaching; Focus on Form Introduction Pedagogical researchers and practitioners have been search- ing throughout the past century for an effective method to tac- kle the “most difficult and persistent part of language learning”, pronunciation. The discussion of pronunciation teaching has come through days of direct method before the reform move- ment, and developed into behavioral (e.g., audiolingualism, Lado, 1964; total physical response, Asher & Price, 1967; Ash- er, 1969) and more cognitive approaches (e.g., the silent way, Gattegno, 2010; desuggestopedia, Lozanov & Gateva, 1988). Both methods stressed pronunciation to be taught by imitation and pattern drills, such as minimal pairs and tape recording- listening. Overall, the teaching of pronunciation was seen as it- self, as a purely psychological factor that requires either beha- vioral stimulus-response cycle or a cognitive-development pro- cess which requires a journey of stages (Stevick, 1976). However, the rise of Communicative Language Teaching (CLT) has the belief that teaching pronunciation should include more meaningful contexts (Celce-Murcia, 1996). CLT was also referred to as “meaning-focused” instruction, which is later challenged by “form-focused” (or Focus on Form, FonF) in- struction because the latter has re-emphasized on the formal and linguistic aspect of language learning (Long, 1998). The debate has been intensive in areas involving reading and speak- ing classrooms but very few studies have empirically tested these two methods in a classroom of pronunciation. According to the Speech Learning Model (SLM, Flege, 1995), L2 sounds that is similar to L1 categor ies are diffic ult to be acquired because their differences will be easily overlooked and the two categories will be classified equivalently. The /r/ sound is presented in the English phonological inventory; and /r/ is at the same time an allophone of the “ri mu”, or “r” onset traditionally transcribed as /ʐ/ in Mandarin. This onset has two allophonic variations with an English-like /r/ and a retroflex fri- cative (Shi, 2012). This distribution of one phoneme correspon- ding to an allophonic variation would make the sound difficult to be categorized because of the L1 influence (Flege, 1987). This study compares the teaching outcome of both CLT and FonF instructions on Mandarin ESL learners’ pronunciation performance of English /r/, especially in cluster, and intends to draw a conclusion that the FonF instruction is more targeted to students and thus more desirable in the pronunciation class- room. Two Teaching Methods: A Review o f Literature Pronunciation Learning in CLT CLT was a very influential teaching method (or more exactly, an approach of teaching) that emphasizes on the importance of involving real communication in language teaching. In its sup- porters’ point of view, only involving communication in teach- ing would give students authentic input, as the function of lan- guage is communicative (Widdowson, 1978). The discussion of CLT had been very popular in pronunciation education. It has been explicitly explained as follows, representatively. “This focus on language as communication brings renewed urgency to the teaching of pronunciation, since both empirical and anecdotal evidence indicates that there is a threshold level of pronunciation for nonnative speakers of English” (Hinofotis & Bailey, 1980). The importance of communicative intelligibility was brought  Y. Z. LAN, M. J. WU Copyright © 2013 SciRes. about by Derwing and Munro (2005). His work confirmed that learning can only be effective when communication takes place. Many other studies echoed this idea and it had become an im- portant message CLT delivered on L2 pronunciation teaching. Morley (1994) had pointed out that heavy cognitive loads in independent speech tasks would lead to more pronunciation errors and hence it is necessary to incorporate guided practice and spontaneous speech together in an integrated curriculum. In his curriculum guidelines for instructional planning of pronun- ciation courses, a practice mode that moves from dependent practice through guided practice to independent practice was introduced. The last one was represented by an extemporaneous speech, which gave students full freedom to generate their own meaningful speech. The communicability of pronunciation practices should be included in the curriculum and more authentic materials, as well as native speakers as teachers should be utilized as part of the communicative logistics of the classroom as a part of its function (Celce-Murcia, 1996) to approximate the real-time si- tuation in language contact. The core of CLT is creating a genuine context which invol- ves the negotiation of information (Widdowson, 1978). How- ever, it seems to be only useful for information processed as long-term memory that has discrete functions, such as the di- verse semantic and pragmatic functions of a certain expression. For lower-end elements, such as L2 phonology, the “function” is not defined in the meaningful context inherently and is more easily interfered by L1 than lexical or syntactic constraints (La- do, 1961). Moreover, in a UG perspective of L2 acquisition, phonology may also become fossilized more easily in devel- opment (Krashen & Terrell, 1988). The predecessors of CLT might have already noticed the li- mitation of CLT in guiding the teaching practices in the pro- nunciation classroom. Guidelines of CLT-based pronunciation curriculum has always been a blend of both formal and mea- ningful tasks, as Celce-Murcia (1996) has identified, the major activities in a communicative pronunciation classroom should include “listen and imitate, phonetic training, minimal pair drills, contextualized minimal pairs, visual aids, development appro- ximation drills, reading aloud or recitation” are just echoing back methods used in the behavioral and cognitive times. The innovation lies in putting the drills in a real-time communica- tion framework, such as contextualized minimal pair practice, to stimulate students’ pronunciation learning through meaning- ful contexts. Interestingly, Foote et al. (2013) recently found, through a corpus-based study, that c ommunicative language teac hing could be more effective in pronunciation when real-time contextua- lized feedback is given to students. Learning was proved to be in effect when spontaneous recast was given to students. This is actually a core concept in form-focused instruction. It may seem that this method, though less discussed in the context of pronunciation learning, might be of some merits. Pronunciation Learning in Focus on Form The primitives of speech is still linguistic, and we all resort to linguistic form of speech sounds to get the meaning across, no matter the primitive is acoustic (Kuhl, 2000) or gestural (Fowler, 1986). The method of FonF was born under this consideration. It is argued that classroom feedback of recast (Long, 1998; Doughty & Williams, 1998). FonF instruction is a method of L2 instruc- tion focusing both linguistic forms and communication. It is an alternative to focus on meaning instruction of the school of Na- tural Approach (Krashen & Terrell, 1988), which prohibits di- rect grammar teaching and promotes natural input of L2 texts and listening materials only. The defect of meaning-focused in- struction becomes clear “when classroom second language learning is entirely experiential and meaning-focused” (Dough- ty & Williams, 1998). FonF will enable students to contemplate after absorption of language knowledge, which is a precious process of self- learning after class, and will also foster interaction between the instructor and students, because the discussions of linguistic forms is much inclusive, interesting and inspiring than mere imitation. The FonF method has been widely used in linguistic forms other than phonetic acquisition in L2 English teaching. For example, in syntax, instead of solely presenting sentences for students to pattern after, instructors often make use of ge- nerative grammar to introduce abstract terms like NP, VP and clauses. But there are no previous empirical studies that test whether focus on form can be applied in pronunciation instruc- tion by experiment. That is why this study is proposed and I think this study will serve as a ground-breaker in broadening this method's application in Greater China, which is of some significance. However, the biggest problem of the method is to avoid ex- cessive theoretical dogmatization in instruction. Language lear- ners are not expected to, nor interested in (in most cases) of the complex anatomical, phonetic and phonological aspects of the speech sounds. Simply giving them form-focused linguistic in- formation will do harm to their motivation and increase an- xiety, which will in turn affect learning outcomes (MacIntyre & Gardner, 2006). Method Two groups of participants, namely the experiment group and control group, were given 15 minutes of CLT and FonF in- structions about the English /r/ cluster respectively. Before and after the instruction, a pre-test and a post-test were done for both groups. Their task is to read a short discourse with stimuli embedded inside. Their productions were examined by both acoustic measuring and native speaker perception. Parti ci pa nt Participants were ten adults enrolled as students of Master of Arts in Translation program at the department of Chinese, Translation and Linguistics at City University of Hong Kong (6 females, 4 males, mean age = 25.5). They had over 20 years of learning English and started English learning before the age of 6. They used English as their working language and in their daily communication. They were all raised up from Beijing, with their parents or care-takers speaking monolingual Beijing Mandarin. None of them had exposure to other foreign languag- es except English. All participants were right-handed with no reported hearing or motor-control defects. They did not have prior exposure to phonetic or musical training. For controlling, two native monolingual English speakers (1 female and 1 male, mean age = 26.5) from California, US also participated in the study and went through the same procedure in the pre-test and post-test.  Y. Z. LAN, M. J. WU Copyright © 2013 SciRes. Instruction Two Instruction methods are carried out as below. The two types of instruction were both given in the same classroom with same amount of time (15 minutes). For form-focused instruc- tion, the instruction time was more approximate because of dif- ficulty to control the exact time in this non-syllabus-based me- thod. • CLT Instruction For communicative language teaching, the plan follows the major activities brought about by Celce-Murcia (1996) as much as possible to be applied to the instruction of /r/. Students first read aloud the material to be tested in the study for five minutes. Teacher will give students guidance and stu- dents will do role play to take turns to read as well. After that, contextual minimal pair exercise will be done for students for five minutes. Minimal pairs should consider /r/-/w/ contrast, /r/-deletion contrast and /r/-/l/ contrast, which is found in many studies (Hung, 2002; Chan, 2006; Au, 2002). First, a listening exercise will be conducted by playing native English speakers’ production of sentences like “I would like to buy the toy ring” and “I would like to buy the toy wing”; “Could you help us watch the load?” and “Could you help us watch the road?” • FonF instruction For form-focused information, recasting were used when stu- dents have problem of pronouncing the /r/ because recasting rather than deliberate syllabus-based learning is the core to form-focused pedagogy. However, a detailed general guideline is listed below to serve as a summary of how formal instruction may be effectively given when students are in need. Firstly, the knowledge of basic theory of articulatory phonet- ics could help students whose pronunciation has already been partly fossilized to improve pronunciation. These students may have problems to manage right sounds because they don’t have the knowledge of exact variables to control a sound and articu- late it. If students depict problems of articulator control of the /r/ sound, here is a sample recast for the student. Firstly the teacher will give out a description of /r/ sound: /r/ is an appro- ximant, and there are two variations for initial /r/: curled /r/ and bunched /r/ by different varieties of English speakers. It con- tains three major gestures: tip-curling or raising (Tongue Tip), tongue body retracting (Tongue Body) and lip-rounding, and teacher will demonstrate with his own voice and the comput- er-aided demonstration as well (Browman & Goldstein, 1992). Contrast with gestures of /l/ (Tongue Tip and Tongue Body but contact alveolar ridge) and /w/ (more Lip protrusion and no Tongue Tip gesture) will also be demonstrated. Secondly, the aid of visual phonetics can make theories easi- er to understand. After all, the whole system of phonetics may- be too informative to learn by heart easily and the textual in- troduction seems tedious and scattered. A pioneering example was a Spanish pronunciation learner's helper created by Barru- tia (1970) into our types of instruction activities, which can be easily adapted, catering to English pronunciation learners. Here, to help students understand the abstract movements in the vocal tract which is not easily seen, an fMRI mid-sagittal display with highlighted places of gestures will be given to students. To further provide visual aid, hand gestures can be given to stu- dents. Different from previous groups using arbitrary symbols, we use hand gesture to imitate tongue positions. It might be more iconic and easier for student to recall after they find con- fusion again in later production (see Figure 1). Basic knowledge of syllable structure will enable students to improve pronunciation with a more targeted awareness for er- rors concerning the L2 syllable. For example, mainland stu- dents intend to add a schwa sound in between initial consonant- r clusters. It will influence the /r/ production in the cluster, part- ly because of lack of knowledge in the difference of syllable structures (the syllable of Mandarin being [(C)V(C)] and Eng- lish being [(C)(C)(C)V(C)(C)(C)(C)]). Stimuli for Tests Identical stimuli words containing initial clusters were used for both Mandarin and English speakers. Stimuli consisted of three types of words: target words and two types of control words. Target words were real words containing initial C-r clu- sters (e.g., break, treat, and great). All stimuli words were gua- ranteed of high word-frequency by choosing them from a pri- mary school word list (Graham et al., 1993). Word frequency was considered to ensure that all participants read the stimuli fluently and easily. Target words were measured for acoustic reliability for the physical property of /r/ according to four variables: (a) The third formant value (F3). This is a measurement used in Lehiste (1962). (b) The distance between the F3 and the second formant (F2). This is al so a mea surement used to distinguish /r/ with other ap- proximants (Ladefoged & Johnson, 2010). (c) Duration of the r, which can be used to see whether /r/ has been fully art iculated. (d) Native speaker’s perception, in the procedure of 0 and 1 force-choice of whether the sound is native-like, was done as well. Filler words are chosen to contrast with the target words in two ways: For contrasting C-r cluster with non-[r] environment, words with single stop initial such as bit, tip, and keen are cho- sen; for contrasting C-r cluster with an environment without onset plosives and to see if cluster [r] is assimilated to other approximants, words with single liquid or glide initial such as rear, win, and lean are chosen. These words were not included in the data analysis. All stimuli were put into a coherent short passage (see Ap- pendix) to ensure that all participants read the stimuli fluently and naturally in conversational style, without any problem in Figure 1. Hand gestures imitating tongue pos ition by the instructor and also to be performed by students: the gesture of /r/ is on the left and /l/ on the right. The fingers represent tongue tip and the palm represents tongue dorsum.  Y. Z. LAN, M. J. WU Copyright © 2013 SciRes. spelling out the words. Some originally included stimuli tokens are deleted because the vowels are articulated significantly wrong. e.g., pronouncing “grind” as [grInd]. Originally we designed a set of stimuli consisting of six to- kens per place category with distinction on vowels. But it is extremely hard to control the vowels and at the same time keep the word frequency high, so we did not control strictly about the vowel distribution. As a result the number of tokens is alto- gether 55 for each speaker in the pre-test and post-test. So in total there are 55*10 = 550 tokens for Mandarin participants and 55*5 = 275 analyzed. Procedure for Tests All participants did the recordings in the Research Laborato- ry for Phonetic s and Cognitive Studies at City University of Hong Kong. They were recorded at the sampling frequency of 44100Hz in mono channel. Participants were instructed to read the passage three times and for each stimulus, the steadiest word in three repetitions was picked for analysis. Speakers were asked to sit in front of the recording apparatus and read the stimuli with chair height adjusted to their ease of reading. Microphone was placed with a 10 cm, 45 degree dis- tance away from the speaker’s mouth. The stimuli sheet, both pages in a paper stand, was placed in front of the speakers’ eye and subject to the speakers’ adjustment. The font size was 24. Speakers have the chance to try and familiarize with the equip- ment. The researcher left the room while recording was in pro- gress. Result Difference by Mandarin and English Speakers Acoustical differences of F3 and F3-F2, especially F3, are both significant for Mandarin and English speakers for both pre-test [F3: t = −8.292, df = 548, p < .0001; F3-F2: t = −4.828, df = 548, p < .001] and post-test [F3: t = −8.630, df = 548, p < .0001; F3-F2: t = −6.560, df = 548, p < .0001] and overall [F3: t = −10.616, df = 823, p < .0001; F3-F2: t = −6.823, df = 823, p < .001]. The bar-chart of overall difference of Mandarin and English speakers’ measurement was shown below (see Figure 2). Duration data was not collected for native English speech due to technical reasons, and will be compared in the group- wise results in the next section. Difference by Groups The comparison of pre-te st and post-test i n control and expe- riment groups will be presented below. For the experiment group, the difference between the pre-test and post-test was significant in all three measurements (F3, F3-F2 and duration) [F3: t = 2.039, df = 548, p = .04, F3 -F2: t = 1.989, df = 548, p = .50, duration: t = −9.183, df = 548, p < .0001] (see Figure 3). However, for the control group, the difference between pre- test and post-test is only significant for duration [t = 6.199, df = 548, p = .014], near-significant for F3-F2 [t = 3.817, df = 548, p = .053] and insignificant for F3 [t = 0.813, df = 548, p = .910,] (see Figure 4). The difference in native English speakers’ perception result changes across the pre-test and the post-test is larger in the Figure 2. Overall comparison of F3 and F3-F2 values (in Hz) in E nglish an d Mandarin speakers’ production (irrespective of groups and tests). An F3 value which is lower th an 2000 Hz indicates a canonical /r/ production. The Blue bar re pre s ents F3 and The gree n bar, F3-F2. Figure 3. Comparison of pre-test and post-test’s F3, F3-F2 (in Hz) and du- ration (in ms.) values in Mandarin experiment group’s production. An F3 value which is lower th an 200 0 Hz indicates a canonical /r/ production. The Blue bar re pre s ents F3 and The gree n bar, F3-F2. Figure 4. Comparison of pre-test and post-test’s F3, F3-F2 (in H z) and du- ration (in ms.) values in Mandarin control group’s production. An F3 value which is lower than 2000 Hz indicates a canonical /r/ production. The Blue bar re pre s ents F3 and The gree n bar, F3-F2.  Y. Z. LAN, M. J. WU Copyright © 2013 SciRes. experiment group (69% and 74%) than control group (65% and 68%). [F (3, 546) = 4.578, p < .05] (see Figure 5). General Discussi on The results of acoustic difference by Mandarin and English speakers in an overall manner had showed that Mandarin and English speech of /r/ do have significant differences acousti- cally. The difference in individual pre-test or post-test also echoes back the same significance level. The acoustic comparison of control (CLT instruction) and experiment (FonF instruction) groups showed that the acoustic improvement patterns are different between the control group and the experiment group. In the control group, only the im- provement of duration is significant. F3-F2 is near-significant as well. However, we should note that the F3 indicator for /r/ quality is the most important one, and the significance of F3-F2 without a significance of F3 only indicates the change of F2, which corresponds to more global tongue positions in the vocal tract, and is not a desirable result for improvement of /r/. Therefore, the spectral aspect did not improve much for the control group. Probably it is because in a communicative in- struction environment, students are more sensitive to prosodic factors, and hence temporal cues of speech sounds rather than spectral cues. This has been introduced by Celce-Murcia (1996) in the main effect of CLT application in pronunciation. In fact, supra-segmental features of pronunciation are more emphasized in CLT-based syllabi (Morley, 1994). On the contrary, the experiment group had significant im- provement in all three aspects, indicating a full-ranged im- provement on the pronunciation. This is probably due to the ability for form-focused instruction to give direct and compre- hensive recasts immediately after an occurrence of a pronuncia- tion error (Long, 1998) irrespective it being spectral or tempor- al. Moreover, all errors are not responded just by repetition of the sound stimuli which can only have influence on the sensory store, but also by linguistic knowledge and articulatory me- chanisms which could be restored in the learner’s long term memory or to be rote-learned and work as self-generated feed- backs when similar errors occur again. Therefore, we could in- clude FonF as a useful method in teaching speech sounds. Figure 5. Comparison of native speaker perceived accuracy rate in the control group’s pre-test and post-test (two bars on the l eft) and the experiment group’s pre-test and post-test (two bars on the right), respectively. Moreover, the perception data by native English speaker across the pre-test and post-test had improved more signifi- cantly in the experiment group, than that in the control group. Therefore both physically and perceptually, FonF method would introduce more improvements in this case. From the results we could see clearly that the effect of tea- ching in FonF method is better than CLT. However, a cautious explanation of this result would be concerned on the limitation of the procedure. As has been touched upon in the literature review, the FonF method is inherently a highly spontaneous teaching method independent from a pre-designed syllabus. The effect of which is highly dependent on the experience and competence of the instructor. Therefore, the effect of both methods should also be examined by different instructors. However, due to lack of re- sources and difficulty of controlling the variant of teaching performance, especially the effect of recast in FonF which may vary on the specific situations, only one instructor, the resear- cher, had participated in the instruction. Conclusion This study has examined, from both the perspective of acou- stic quality and perceptual native-likeness, the effect of two teaching methods of pronunciation of /r/ in cluster. At least in the current case, we could arrive at a conclusion that pronuncia- tion teaching can be better assisted by form-focused learning rather than a communication context because of its ability to capture both temporal and spectral errors in speech. Acknowledgemen t s The authors thank Sunyoung Oh for her suggestions to an earlier draft of this article. REFERENCES Asher, J. J. (1969). The total physical response approach to second language learning. The Modern Language Journal, 53, 3-17. Asher, J. J., & Price, B. S. (1967). The learning strategy of the total physical response: Some age differences. Child Development, 1219- 1227. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1127119 Barrutia, R. (1970). Visual phonetics. The Modern Language Journal, 54, 482-486. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.1970.tb03582.x Browman, C. P., & Goldstein, L. (1992). Articulatory phonology: An overview. Phonetica, 49, 155-180. http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000261913 Celce-Murcia, M . (1 99 6). Teaching pronunciation audio cassette: A re- ference for teachers o f English to speakers of other la nguages. New York: Cambridge University Press. Derwing, T. M., & Munro, M. J. (2005). Second language accent and pronunciation teaching: A research-based approach. TESOL Quar- terly, 39, 379-397. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3588486 Doughty, C., & Williams, J. (1998). Focus on form in classroom se- cond language acq uisition. New York: Cambridge University Press. Flege, J. E. (1987). The production of “new” and “similar” phones in a foreign language: Evidence for the effect of equivalence classifica- tion. Journal of Phonet ics, 15, 47-65. Flege, J. E. (1995). Second lang uage speech learning: Theory, findings, and problems. In W. Strange (Ed.), Sp eech perception and linguistic experience: Issues in cross-language researc h, 233-277. Foote, J. A., Trofimovich, P., Collins, L., & Urzúa, F. S. (2013). Pro- nunciation teaching practices in communicative second language classes. The Language Learning Journal, ( ahead-of-print), 1-16. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09571736.2013.784345  Y. Z. LAN, M. J. WU Copyright © 2013 SciRes. Fowler, C. A. (198 6). An ev ent app roach to the stud y of speech percep- tion from a direct-realist perspective. Journal of Phoneti cs, 14, 3-28. Gattegno, C. (2010). T eaching foreign languages in s chools: The silent way. Educational Solutions World. Graham, S., Harris, K. R., & Loynac han, C. (1993). The basic spelling vocabulary list. The Journal of Educational Research, 86, 363-368. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00220671.1993.9941230 Ingram, D. E. (1974). Beyond audiolingualism—A linguistic and psy- cholinguistic view. Babel, 10, 9-15. Krashen, S. D., & Terrell, T. D. (1988). The natural approach: Lan- guage acquisition in the classroom, language teaching methodology series. Kuhl, P. K. (2000). A new view of language acquisition. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 97, 11850-11857. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.97.22.11850 Ladefoged, P., & Johnson, K. (2010). A course in phonetics. Wads- worth Publishing Company. Lado, R. (19 61). Language testing: The construction and use of foreign language tests: A teacher’s book. Bristol, Inglate rra: Lon gmans, G reen and Company. Lado, R. (1964). Language teaching: A scientific approach. Lehiste, I. (19 64). Acoustical characteristics of selected English conso- nants. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University. Long, M., & Robinson, P. (1998). Focus on form: Theory, research and practice. In C. Doughty, & J. Williams (Eds.), Focus on form in classroom second language acquisition. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. MacIntyre, P. D., & Gardner, R. C. (2006). Methods and results in the study of anxiety and language learning: A review of the literature. Language Learning, 41, 85-117. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-1770.1991.tb00677.x Morley, J. (1994). Pronunciation pedagogy and theory: New views, new directions. TESOL, 1600 Ca meron Street, Suite 300, Alexandria, VA 22314. Scovel, T. (1983). Emphasizing language: A reply to humanism, neo- audiolingualism, and notional-functionalism. M. A. Clarke and J. Handscombe, 85-96. Shi, F. (2008). Yuyin Geju, phonetic patterns. Beijing: Shangwu. Stevick, E. W . (197 6). Memory, meaning and method: Some Psycholo- gical perspectives on language learning. Widdowson, H. G. (1978). Teaching language as communication. New York: Oxford University Press. Appendix Hello everyone, my name is Bree. My topic of the presenta- tion today is my dream. //I have a great dream. I want every friend of mine can afford the fee of the train to many places. //I also want them to pray, just like a priest, so they don’t have to wash and dry t heir clothes every day. //And they can drink milk and eat bread without looking at the price or paying a tip. Moreover, my friends can draw everything they want to try, and they can grow many big apple trees in their gardens. //By the way I hope my brave friends won’t drop from the top to the ground and then died. //Instead, it’s much better to glide from the tree and after that they can lean on it and have some rest. //And at school, I wish they don’t have to do group presenta- tions in front of the class president, because they can just flee away like a cat. //And when they play football after school, they won’t cry even if a truck has hit them. //Instead, they can bring the football home or go for a trip even if their legs broke. Again, sometimes when you pray, you can get more money to pay for things you dream of. //Like now, my stomach is dead crazy for a bite of fried chicken burger with raw onion! //And get me some seaweed and crisps! By the way do you know the crazy story of the frog prince? //I’m so keen to it. I thought the princess is so proud of herself and I cry every time when I read it. Well boys, soon will be Halloween and be bright! Remember to say “trick or treat” to get sweeties. //Even you face the risk of crushing with each other, it’s OK. //You can still find a way to win the game. Lead your team and rob for free sweeties! //After that your friends and parents will even pay the price of a cream soda for you after you are bumped blue and green. //Well, I think it’s time to lie down and sleep but I grind my teeth every night when I dress on my clean night gowns.

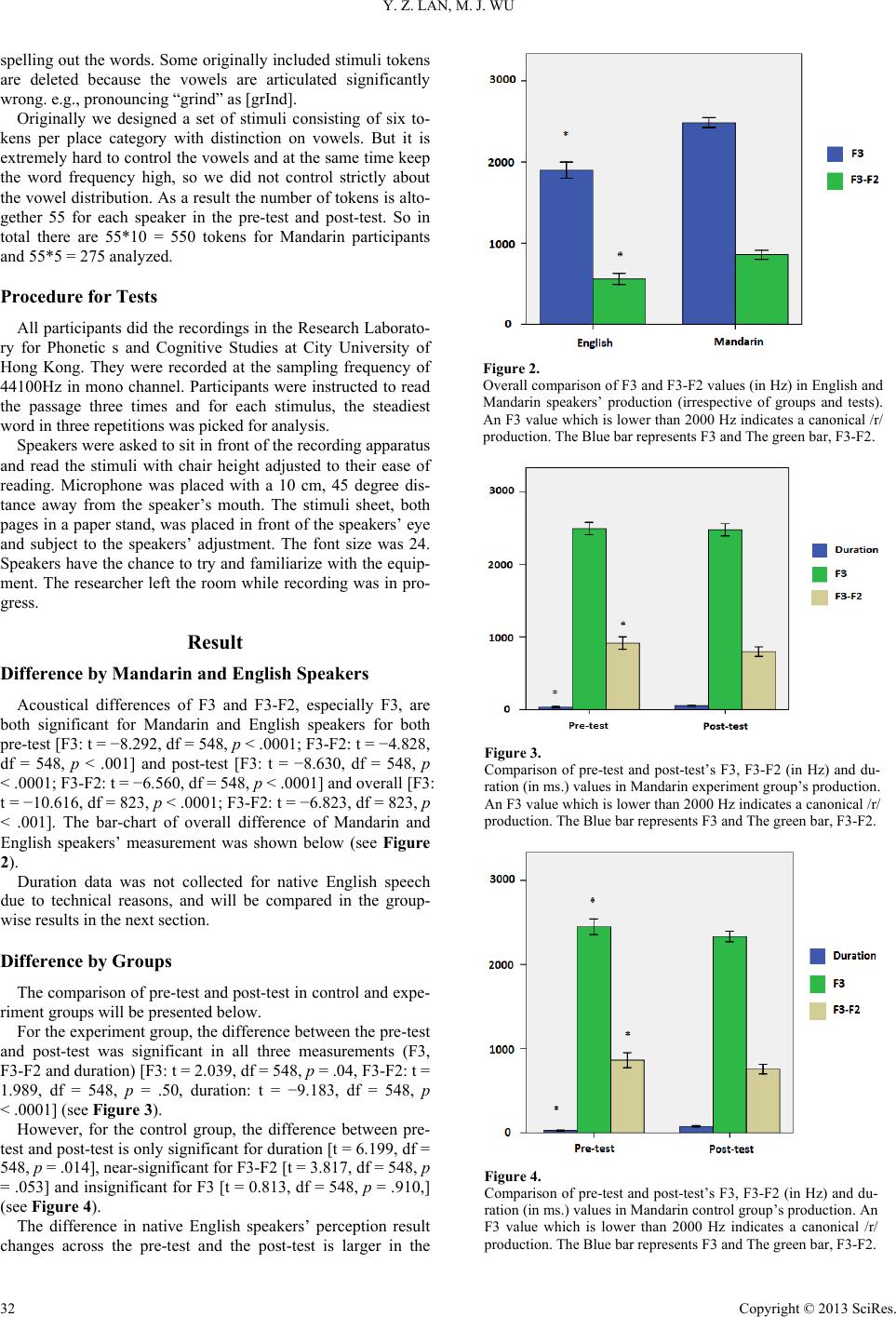

|