Open Journal of Nursing, 2013, 3, 379-388 OJN http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojn.2013.35051 Published Online September 2013 (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ojn/) Constructing family identity close to death Ida Carlander1,2, Britt-Marie Ternestedt1,3, Jonas Sandberg1,4, Ingr i d Hel l st rö m 1,5 1Palliative Research Centre, Ersta Sköndal University College & Ersta Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden 2Department of Learning, Informatics, Management and Ethics, Medical Management Center, Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, Sweden 3Research and Development Unit, Stockholm Sjukhem Foundation, Stockholm, Sweden 4Jönköping Department of Nursing, School of Health Science, Jönköping University, Jönköping, Sweden 5Department of Social and Welfare Studies, Linköping University, Norrköping, Sweden Email: ida.carlander@erstadiakoni.se Received 28 June 2013; revised 28 July 2013; accepted 15 August 2013 Copyright © 2013 Ida Carlander et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. ABSTRACT Daily life close to death involves physical, psycho- logical, and social strain, exposing patients and their family members to major transitions affecting rela- tional patterns and identity. For the individual family member, this often means sharing life with a chang- ing person in a changing relationship, disrupting both individual identity and family identity. Our aim was to deepen the understanding of individual experiences that are important in constructing family identity close to death at home. We performed a secondary analysis of qualitative data collected through 40 in- terviews with persons with life-threatening illness and the family members who shared everyday life with them. The analysis resulted in interpretive descrip- tions which provided three patterns important for creating family identity, which we here call “we-ness” close to death. The patterns were: being an existential person, being an extension of the other, and being together in existential loneliness. Together, these three patterns seemed to play a part in the construc- tion of family identity; we-ness, close to death. One important finding was the tension between the search for togetherness in “we-ness” while dealing with an existential loneliness, which seemed to capture an essential aspect of being a family of which one mem- ber is dying. Keywords: Dying; Identity; Family; Palliative Care; Secondary Analysis 1. INTRODUCTION This article is based on human experiences of everyday life at home, when one person in the family is severely ill and dying. We focus on central concepts such as identity, death, and togetherness. In the context of palliative homecare, daily life for both patients and their family members means facing physical, psychological, and so- cial strain. For the family member, it also means sharing life with a changing person in a changing relationship. Life-threatening illness causes a rupture in a well-estab- lished rhythm [1], marking a transition and simultane- ously a time of limbo [2]; the result of this is a d isruption in identity. According to Schumacher and Meleis [3], the concept of transition can be useful when exploring the experience of individuals facing periods of instability, for example when a family member is dying. Family mem- bers are often involved in caregiving in several ways, and have to deal with a series of new events which might occur either suddenly, or gradually over a longer time. The ill person’s body may be attached to medical devices or tubes, and may need potent drugs and a number of auxiliary devices. The care team enters the home, bring- ing these materials, drugs, and auxiliary d evices; this not only impacts on family life, but also sometimes changes the home environment itself [4]. In this changed every- day life, the focus shifts to the dying p erson’s illness and treatment, which affects all involved emotionally, so- cially, and physically [5]. Family caregivers, for example, have been shown to suffer from sleep deficit [6]. Despite distress and burden, many people prefer to live and die in their own homes [7,8]. From the perspective of family members, caring is often described as something natural and, despite the strain, well worthwhile [9-13], at least from a retrospective perspective [14]. For both the dying person and their family members, living close to death means being aware of and dealing with one’s own finitude. Jaspers [15] refers to death as one of mankind’s existential limitations, and uses the term “border situations” to describe confrontations with impending death. Spiritual and existential needs become especially prominent during life close to death [16-19]. OPEN ACCESS  I. Carlander et al. / Open Journal of Nursing 3 (2013) 379-388 380 Death itself is seen as an individual event, but one that must be dealt with in the family and social network. So- cial relations are of essential importance for wellbeing in end-of-life care [20,21]. When closeness to death be- comes a part of everyday life, it can be difficult to remain the “same family as before” [22,23]; in such situations, family members face the loss of both their mutual future [24] and the image of themselves as a family [25]. Eve- ryday life close to death means that previous patterns of doing things together will not always work, and may need to be rethought [2 5,26]. In an earlier project studying families’ everyday life close to death, we developed two concepts which we found useful in exploring identity work within these families: me-ness and we-ness [author]. Me-ness was used to describe individual identity, regardless of whether the individual in question was the ill person or a family member, and we-ness was used to describe a group iden- tity embracing the ill person and their closest family members. Erikson [27] argues that identity is developed in a complex social context, and is a configuration of the self that develops over time; it is not fixed and frozen. Hence, we-ness could be seen as a collective identity present in the shared and interactive experiences of eve- ryday life close to death [25]. It is likely that the sense of we-ness might shift over time, to include more or fewer people. Studies in palliative care describing positive aspects of relations at the end of life have found togetherness to be a relevant concept in terms of relations between family members, friends, professional caregivers, and other pa- tients [28-35]. According to Milberg and Strang [36], togetherness involves trust, shared responsibility, and being a resourceful contributor to the care process. To- getherness has also been described as the opposite of social loneliness and isolation [36-38]. Togetherness and belonging could be examples of positive feelings which make family membership meaningful and characterize a sense of group identity. Even though being close to fam- ily members and sharing togetherness have been found to be important when one family member is dying, there have been few and sparse explorations of the aspects of individual experiences that are important in constructing family identity close to death. Hence, the aim of this study was to deepen the understanding of individual ex- periences relevant to constructing family identity; we- ness, close to death at home. 2. METHODS This study is based on a secondary analysis of interview data collected in 2004 and 2008 [14,22]. Initially, the qualitative data used here was used through two distinct inquiries that fo cused on similar to pics using comparable research methods. The overall aim was to advance un- derstanding about family members’ everyday life close to death at home, with a focus on identity (Table 1). In qualitative second ary analysis, the potential of one’s own data has been recognized [39]. Secondary analysis is thought to be an appropriate approach when the intention is to answer extended questions [40]. For this current paper, both sets of data were reanalyzed to answer ques- tions related to experiences relevant for constructing family identity in daily life close to death. During the analyses, we kept the focus on the individual’s experi- ence on the shared everyday life. The analysis was un- derpinned by the idea that narratives are connected to the construction of both an individual and a group identity [41]. 2.1. Participants The sample from 2004 consisted of ten family caregivers who had cared for a diseased family member at home 6-12 months earlier, all of whom were interviewed indi- vidually. The sample from 2008 covered five families, from which 5 patients and 14 family members (Ta ble 2) participated in 30 interviews (18 individual, 8 couple, and 4 family interviews with 3 to 4 persons) with differ- ent time gaps of 2 to 18 months between the first inter- Table 1. Original studies. Study Opening question Data, period of sampling Results Data analysis [14] Can you tell me how your life was when X was ill? Interviews with 10 family caregivers 2004 Three patterns characterized the experiences: “challenged id e a l s ” , “stretched limits” and “interdependency ”. These patterns formed the core theme: the modified self Interpretive description [43,44]. [22] Can you tell me about your current life situation? Interviews with 5 patients and their 14 fa mil y membe r s 2008-2009 We found two patterns: “being me in a family living close to death” and “being us in a family living close to death” while “striving for t he optimal way of living close to death” presented as the core theme. Interpretive description [43,44] Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  I. Carlander et al. / Open Journal of Nursing 3 (2013) 379-388 381 Table 2. Characteristics of study participants. Characteristics 2004 2008 Total Gender Male 3 8 11 Female 7 11 18 Age 5 - 15 3 3 >29 1 1 30 - 39 1 1 2 40 - 49 4 5 9 50 - 59 0 6 6 60 - 69 4 1 5 >70 1 2 3 Illness Cancer 3 3 Heart disease 2 2 Relation Ill person 5 5 Child 3 5 8 Grandchild 1 1 Sibling 1 3 4 Partner 6 5 11 view and last for each family. All 40 interviews took place at a location of the participants’ choice, often around the kitchen table in their homes. The interviews lasted between 1 and 2 hours, and were recorded and transcribed verbatim. The opening question was: “Can you tell me about your daily life?” The interviewer then asked probing questions to explore and gain a deeper understanding of the situations and experiences that the participants considered challenging, as well as those that they considered to promote wellbeing in their life situa- tion. The first author (I.C.) conducted all the interviews except for five interviews performed in 2004. A full de- scription of the study procedures is published elsewhere [author]. All participants lived in a middle-class neigh- borhood consisting of multiple dwellings in a large city in central Sweden. The participants had access to ad- vanced palliative home care. All individuals who were asked agreed to participate in the project. Written consent was obtained from all participants, and the study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical Fac- ulty in Stockholm (ref: 04-047/2) and the Regional Ethi- cal Review Board in Uppsala, Sweden (ref: 2008/051). 2.2. Analysis An interpretive description approach [39,42-44] was se- lected to guide the thematic, secondary analysis of the data set of 40 interviews. All interviews contained rich descriptions of how family members handled daily life close to death. During the exploration of the phenome- non of family identity construction, the following broad research question guided the analysis: what characterizes the individual experience in a family close to death? The inductive analysis was performed via a cyclic movement between all data, and between cases. Although the analy- sis did not proceed entirely in a step by step fashion, the following procedures guided the analysis. The research question directed the reading. Broad-based codes and descriptions were produced to enhance the initial inter- pretation. Next came a systematic analysis of the de- scriptions which had similar meanings and seemed to be thematically linked. The resulting interpretations were examined and grounded in the data set; the three dimen- sions were na m e d as part of t hi s procedure. 3. RESULTS We found three interconnected patterns conceptualizing aspects of individual experiences relevant for construct- ing family identity close to death at home. The first, “being an existential person”, describes the need to be seen and respected as a person living close to death. The second, “being an extension of the other”, covers both the fundamental and insightful practical work that takes place, and a responsibility for problems arising in rela- tion to the ill person’s uncooperative physical and some- times mental functions. The third pattern, “being together in existential lon eliness”, exemplifies ho w being together can sometimes alleviate the suffering and grief connected with life close to death. Th ese three aspects of individual experiences were connected to the construction of family identity: we-ness (see Figure 1). Figure 1. Patterns conceptualizing aspects of experiences rele- vant for constructing family identity close to death at home. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  I. Carlander et al. / Open Journal of Nursing 3 (2013) 379-388 382 3.1. Being an Existential Person The first pattern of individual experiences was seeing oneself as a person close to death, regardless of whether one is the dying person or another family member. The dying person was in transition to being dead—something unknown—and this situation brought thoughts on exis- tential matters to the surface. Facing up to the end of one’s existence was a lonely task, but being a family of- fered the opportunity to deal with everyday life close to death together. On some occasions, the exploration of existential questions led to thinking of loved ones who had alread y died. One dying man spoke about his thoughts regarding life after death: I have a very strong belief that … when I die … I don’t believe it will be painful in any way. It will be more of a relief. Then you end up … then I’ll see my grandfa- ther and grandmother and other relatives. And yes, meet Jesus and God, and ask forgiveness of the angels who had to … wh o have worked so hard to keep me alive. This man’s existential and religious values were brought to the fore by his limited remaining life, and the construction of we-ness went beyond his living family. The narrative could be interpreted as a transcendent ex- perience—as being in contact with higher values—but he is also being comforted by the thought of meeting close relatives who had moved to the state of being dead be- fore him, maybe giving him hope of a prolonged exis- tence after death. The family members had to deal with the knowledge that one person in the family would die soon while the others continued living, involving a role transition for those who would become, for example, widowed or parentless. This gave a new meaning to the experience of everyday life, and created insecurity and uncertainty among all family members. Both the dying person and their family members tried to integrate their earlier self-image with the new role of a person receiving and/or giving care, while trying to keep their relationship intact. A sister gave an example of this: … he had trouble understanding what he was sup- posed to do with those diapers… He put them on but still peed [urinated on] himself. When he had peed through them… I thought it was very, very difficult, because it was so private. It was difficult, as a sister, to try to get it to work for him. However, being engaged in, and feeling responsible for, making family life work seemed to confirm feelings of being a person of value. Experiences such as being a part of a greater whole, being loved, and being someone who mattered for another person seemed to alleviate feelings of losing control when the known existence was challenged. A diminishing social life was described, and the family members played vital roles as listeners to the dying person’s and each other ’s life stories. Being able to share memories and talk about life as it was earlier ap- peared important not only for constructing individual identity (me-ness), but also for constructing family iden- tity (we-ness), as it gave a reminder of all parties’ earlier roles and functions within the family. These were re- minders of special situations that were of particular value, as they gave some sort of acknowledgment to the dying person and to the family as a group as they used to be. Pointing out a shared past and history also seemed to be central when creating a joint we-ness. The manner in which professional caregivers acknowledged the ill per- son and his or her family members mattered for the sense of individual identity (me-ness). One dying woman talked about the lack of access she had to information concerning her body and illness: It’s me. I decide for myself, but this thing that I men- tioned, not being able to sit down with the medical re- cords, not knowing exactly where my tumors are located, that is rather absurd. And there I ... I see the battle as lost; I just don’t have the energy to argue and nag. I’m afraid of being difficult and nagging too much, because that too is some kind of … I need to have some sort of balance … The quotation above implicitly suggests that being treated as unable to read one’s own medical records could also be interpreted as not being trusted to make decisions about one’s own limited remaining life. Thus, being invited to discuss the care plan on a regular basis was one example of promoting feelings of control both for the ill person and for the person in th e caregiving role. The care plan then could be seen as an active part in the life plan, giving a sense of being in charge of planning a unique period in life. Being dependent on others some- times threatened autonomy and obstru cted the possibility to make demands. The woman quoted above experienced little influence on her care plan, and consequently felt less in control over that specific part of life. The pattern of being an existential person was concerned with being me—me-ness—and as such being seen as a unique per- son facing the border of existence, and at the same time being a family member who helped to make family life work. 3.2. Being an Extension of the Other As the ill person’s strength decreased, the family became involved in a series of new practical activities which were often associated with emotional strain, both for the ill person and for other family members. New asymmet- rical relationships developed when family members per- formed caring activities at home, such as giving injec- tions, or keeping tr ack of and administering analgesics or enteral nutrition. Even though caregiving meant being physically close to each other, it was not easy to remain emotionally and/or intimately close in the same way as Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  I. Carlander et al. / Open Journal of Nursing 3 (2013) 379-388 383 before, due to the tubes and smells coming from the ill person’s body and the other bodily changes occurring, for example weight loss. Wife: But of course there’s been a period with a so rt of yuck … don’t come here with your disgusting wounds and all that . Ill person: Yeah, and bugs ... and crap like that … I sure understand that. The fact that I’m full of that, and holes and all those ma rks left after the holes. Behind the remark above, a glimpse can be caught of a threshold for physical closeness; even a sense of disgust, which could influence relations between the family members to a greater or lesser extent. Using humor, laughing together, and joking about the misery was one strategy to handle the concrete and severe situations which occurred in this precarious life situation. A joke could make it possible to talk about the ambivalent ex- perience of helping a loved husband with his hygiene. There seemed to be no limits to what could be joked and laughed about together; all sorts of human shortcomings and even death could be ridiculed. Gallows humor and jargon could be seen as a way of still being “us”, and thus of maintaining we-ness. As the dying person’s condition became worse, the family member often became an extension of the other, compensating for the ill person’s declining physical and mental functions. As the ill person’s increasing physical limitations created gradual change in many day to day activities, the logistics of practical everyday life had to be solved. A severely ill husband talked about his wife with deeply felt gratitude: She stands up for me in an outstanding manner, being helpful as my extended arms and extended legs and ex- tended head and everything else, and I will never be able to pay her back. She tells me that I would have done the sam e thing fo r her, a nd I surely hope so, but I must say I am not sure … but I really hope I would have made all these tremendous sacrifices [that she makes]… Accordingly, the ill person and their family members had to relate to each other in a new way, and adapt to the fact that things had to be done in a different way to be- fore. Work, going to school, and different commitments outside the home were always prioritized even if the ac- tivities were sometimes limited due to demands in the home situation. When the ill person could not communi- cate his or her needs as before due to sedatives or drowsiness, the partner stepped forward and took over even more functions, both practical and emotional, re- lated to the needs of other family members such as chil- dren or elderly persons. It was a challenge trying to fit in the logistics, and to continue living life as much as pos- sible as before. Being an extension of the other also meant having to deal with legal and financial matters both belonging to th e presen t and coming up in th e fu ture, such as matters affecting the survivors’ lives after the death of the ill person, writing a last will and testament, and planning the funeral, all of which were emotionally demanding. Dealing with all the practical matters in everyday life close to death was one concrete aspect of facing individual challenges of consequence for con- structing family identity, or we-ness. Accordingly, being an extension of the other was recognized as a central part of life close to death. 3.3. Being Together in Existential Loneliness Family members h ad to live in a situation which to so me extent was new, and had to adapt to new roles within the family relationship. This meant doing things together in a new way, at a time when the personal sphere diminished and personal priorities had to be put on hold. This ap- plied to both the ill person and their family members, but displayed itself in diverse ways. The need for doing things in a new way was especially obvious to the family members during periods when the ill person was troubled by physical symptoms or worried about the life situation. One man told his story of a shared everyday life some weeks before his brother died: No, I tried to lie down and sleep for a while, but he was so unsettled, and then he managed to get up and sit by the kitchen table and start ph ilosophizin g abo ut thing s, and then I also sat down by the kitchen table, and several times I fell asleep there opposite him, you know. It was just like that, there was nothing strange about it, I was supposed to be with him but I could have practically slept standing up. The smallest peep and I was up again, you know. The story is about sharing a moment around the kitchen table, but not being able to share the experience of the moment. A shared everyday life meant being in- volved in the stress of living with life-threaten ing illness, but not always sharing the individual meaning of it. Fac- ing death, and existential loneliness, was ultimately an individual challenge. The anxiety was handled both to- gether and indiv idually; some family members dealt with it silently, others talked a lot. The family member quoted below emphasized the shared experience as an important aspect of handling everyday life. Well, we have of course experienced this together. It becomes “us” automatically; it’s not something you go through alone. It’s really us both living through this. Family identity, or we-ness, close to death, was not always verbalized but sometimes expressed via a sensi- tivity towards the other person’s experiences. This sensi- tivity came from wanting to understand the other per- son’s world and perspective; it was an act of love. Some participants said they had no choice in this: being close to and caring for the other person was unquestionable, and just a part of being human. One husband described Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  I. Carlander et al. / Open Journal of Nursing 3 (2013) 379-388 384 how he and his wife as a couple had learned to face dif- ficult times together over the years; each new challenge brought a new dimension to their relationship, making them appreciate each other even more. The imminent death of his wife made them connect in an even deeper way than before: And I’m so glad we had all these years together, be- cause it has given us the opportun ity to reach this phase. We have learnt so much. We have fought through so much. I hadn’t counted on this, with the short time they gave us. The quotation above illumina tes how this husband saw the immediate death of his wife as a mediator to reach a new phase of togetherness based on insights gained from her illness. For this coup le, sharing everyday life created a strong sense of community, we-ness, making it possible to handle the ex istential lonelin ess. Sharing everyday life with other family members did not diminish the search for understanding and ways to share the existential meaning with other people. For example, our informants participated in interest groups, or met others in similar situations. In the absence of meeting people face to face, the Internet, TV, books, or movies were common sources, often complementing the purely disease-oriented infor- mation delivered by the health care professionals. Social media were also used to share the experience of being severely ill as well as the family members’ own situation; this method of communication was often expressed as positive and rewarding. The Internet could be used to search for information and research results concerning the diagnosis and treatment, but it also offered advice on how to deal with leaving the children, and offered a way to communicate with others about these matters. The Internet was thus an important part of being together in existential loneliness, since it allowed sharing of experi- ences with others outside the group of family and profes- sional caregivers. 4. DISCUSSION The main findings in this study distinguish three central aspects of individual experiences close to death that are important for constructing family identity: being an ex- istential person, being an extension of the other, and be- ing together in existential loneliness. According to Jen- kins [45], identity is the understanding of who we are and who other people are, and can be seen as a practical matter which involves comparisons of both similarity and difference. Living close to death could be seen both as a situation and as a process that may involve questions of meaning, but also interaction, communication, and negotiation. The relationship between aspects of indi- vidual identity and identity with a group lies in the rec- ognition of “us” (or we-ness) primarily by not being “them”. Our results exemplify some aspects that exag- gerate the similarities between the individuals within their family. These similarities differentiate them from other groups, for example families not living close to death; this is important for creating family identity, we-ness. The first pattern, “being an existential person”, de- scribes the challenges of facing the ultimate existential loneliness close to death. Man is basically alone, and existential loneliness is a given for all humans [35,46]. The results in our study show, in line with the findings of Waldrop et al. [47], that be ing in transition to end-of-life care for family caregivers also meant sharing the short period of life before a loved one’s imminent death, fac- ing the fact of human evanescence [see also 48,49]. Sharing stories, experiences, and thoughts of a mutual family life close to death could be seen as approaching the existential dimensions of life. In doing this, both the ill person and other family members sometimes had to adapt to other people’s points of view, feelings, and reac- tions. Finding oneself as an existential person became evident in a period that was characterized by significant changes, concretized by the ill person’s increasing de- pendency on others [see also 50]. Those living close to death found themselves in a period of change, which affected their sense of individual identity and self-image (me-ness), but also challenged their ways of being a group; a family with a sense of we-ness. It is important to emphasize that individual experiences close to death were complex. The results also show that the ill person had a need for acknowledgement, and needed to share their thoughts about existential questions. Family mem- bers were often engaged in their own grief related to a different transition. Our informants expressed strong feelings of being tied down and being trapped. According to Schumacher and Meleis [3], indicators of successful transition are subjective wellbeing, role mastery, and the wellbeing of relationships—indicators that are closely related to constructing family identity. This could be de- scribed as a transition (Schumacher & Meleis, [3] which affects both the ill person and the surviving family members. In our study, the ill persons perceived that life was soon to end, meaning a final separation from life and family members, an insight brought by the closeness to their own impending death. Schumacher & Meleis [3] call this type of transition “health/illness-related”. For the family members, the transition was situational. This means they were affected by the illness and death of their family member, but transitions concerning death, grief, and mourning are also developmental, being a part of life for all people [51]. No one walks away unaffected. In order to make the everyday manageable, it is necessary to change one’s own accustomed patterns of relations and roles. How this is done will probably be of impor- tance for how daily life is altered. Professional support Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  I. Carlander et al. / Open Journal of Nursing 3 (2013) 379-388 385 plays a significant role, which was also confirmed by our findings. We found that the nurse played a key role in guiding people through these complex passages in life in as successful a way as possible [51]. Being in need of support, whether as a family caregiver or as a patient, did not take away the need to be seen and respected as a competent person. This has been described in other stud- ies as being offered partnership in the care with the health care professionals [52]. Ward-Griffin and Mc- Keever [53] describe four types of nurse-family care- giver relationships: nurse-helper, worker-w or ker, manager- worker, and nurse-patient. The second type, also de- scribed as a co-workers’ relationship, is based on ac- knowledging the expertise of the family members. Sahl- berg-Blom et al. [54] describe four variations of patient participation in decisions about care planning during the terminal phase of life: self-determination, co-determin- ation, delegation, and non-participation. The studies mentioned above emphasize the importance of asking to what degree individuals and family members want to be self-determined and participate in decisions that impact directly on their everyday life. Hence, how and by whom the care is planned may influence the way family mem- bers live their lives, and thus to some exten t is of impor- tance for construction of family identity. In concrete terms, being an extension of the other meant making the day work practically. For instance, there needed to be food in the home, so someone had to go to the grocery store; someone had to take the children to the day care center and school; and so on. Bo th family members and the ill person strived to create normality in an emotionally and physically challenging everyday life. The well-known everyday life was highly v alued in a life period characterized by uncertainty. Creating normality included both doing and being. Some examples of this included finding ways of preserving habits and things which defined and promoted wellbeing, as well as taking time to just be together. One theme that was woven through all three pa tterns was the idea of creatin g as little change as possible in daily routines and habits. This could be interpreted to be one way of holding on to some concrete activities that constructed family identity, we-ness. According to Milberg and Strang [55], retaining everyday life could also represent an aspect of making the current situation meaningful. Other studies have shown that the relationship between spouses was strengthened by caregiving close to death [23,34]. The family members strove to share experiences with each other, but they also needed support from the professional caregivers. In addition, there was also the urge to know more about the illness and treatments; the Internet was used for this purpose. Our findings suggest that humor has an important role when creating family identity, we-ness, in everyday life close to death. This may not be surprising; humor is present in most human interactions. However, few studies illuminate the meaning of humor in palliative care. As explained in a study by Dean and Gregory [56], humor builds relationships, is energizing, and nurtures community; it can also assist in preserving dignity and acknowledging personhood. Humor could also make difficult care situations easier [57], although it cannot alter the reality of terminal illness [58]. It is rea- sonable to assume that jokes and laughter are a liberating force that can help to handle difficulties in life, but that can also preserve both the individual’s and the family’s identity in an altered everyday life. Linked to this are th e concepts of “me-ness” (being me) and “we-ness” (being us) that we have put forward in previous articles [author]. Further research is needed to examine how humor influ- ences wellbeing. There is also a need to examine when humor becomes a hindrance to dialogue, or when it is not in line with the needs of the ill person . According to Hollman et al. [59], a sense of belonging to a family and the feeling of being needed have been found to improve togetherness. Our results indicate that relations and togetherness can alleviate strains such as existential loneliness, in line with other research (e.g. Sand & Strang, [35]. Interestingly, the pattern of “being together in existential loneliness” showed that the search for a new belonging was not exclusively directed to- wards living persons. For example, one of the informants quoted above derived comfort from and got acknowl- edgement by feeling “connected” to those of his loved ones who had already died, and through religious beliefs. A sense of togetherness was also found in sharing ex- periences with other people in similar situations—other family caregivers or others afflicted with life-threatening illness, and hence dealing with their own finitude. The ill people and family members in the present study fre- quently sought information beyond that supplied by pro- fessional caregivers. The finding s also illuminate that the way professional caregivers talked about care planning, death, and dying was important in the everyday life of dying persons and their family members. The partici- pants expressed the need to know what is known about the end of life. The need for communication and straightforward information is well described in the lit- erature [60-62], which may raise the question of how to talk about death and dying, an d whether there is a gap in knowledge. It was not always the knowledge from the palliative care professionals that was the most needed or wished for. The participants appeared to want to share subjective experiences with other people in a similar situation, and to find out their way of thinking about practical, emotional, social, and existential issues. Hence, it seems important to offer different kinds of encounters for the sharing of experiences. In addition, professional caregivers could also serve as facilitators, using dialogue Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  I. Carlander et al. / Open Journal of Nursing 3 (2013) 379-388 386 grounded in the family’s earlier ways of living everyday life to guide the ill person and their family members through the transition. It seems reasonable to assume that this would assist dying individuals and their families in handling the existential challenge of sharing everyday life close to death at home. 4.1. Methodological Considerations This study has some limitations. It is important to con- sider the ethical principles of a secondary analysis [40], such as the participan ts’ informed co nsent. In the present study, this was addressed by checking that the aim of the study was included within the overall aim of the orig inal studies. Another concern is the relation between the re- searcher, as an instrument for data collection, and the quality of the data. Secondary analysis is heavily reliant on the quality of the original data sets. We judged that the data were rigorously collected and captured rich sto- ries. Because of the in-depth interview analysis neces- sary for a qualitative study, we included 29 per sons (par- ticipating in 40 interviews) with experience of living everyday life close to death. However, our purposeful sampling method was effective in including a variety of experiences. To enhance trustworthiness, we performed prolonged engagement via repeated interviews over time, and also did member checking. We started the analysis confident that the phenomenon of interest was well rep- resented and would therefore yield applicable and useful knowledge. Our research objective was to generate a richly detailed and interpretive examination of this com- plex phenomenon, articulated by individuals experienced in living everyday life close to death. The risk of re- searcher bias is well known in all qualitative research, and secondary analysis without doubt holds the possibil- ity of increasing this bias [63]. Peer review and thick descriptions were used to ensure methodological sound- ness. The product of an interpretive description includes elements of both thematic summary and an integrative interpretation of the phenomenon under study. This means that it cannot be generalized, but by providing rich descriptions it is likely that the knowledge can be transferred to other persons living their everyday lives close to death. 5. CONCLUSION Although much has been written about the burdens of everyday life close to death and the existential needs of both persons with life-threaten ing illness and their family members, this study adds knowledge by proposing as- pects of individual experiences relevant to constructing group identity in families liv in g close to death . Exp loring the concept of family identity could contribute to our understanding of what helps people endure, and even benefit from, this special time in life. Togetherness can be seen as a dimension of humanness; a driving force that is especially important when everyday life is turned upside down and everything is changed by life-threat- ening illness. A better understanding of patterns within constructing family identity could be helpful for pallia- tive care profession als supporting patients and th eir fam- ily members in living their everyday lives during the transition to death. Furthermore, being in transition to something new raised existential questions, and togeth- erness and community seemed to alleviate some of the strains related to everyday life close to death. Family identity close to death thus incorporated the tension be- tween searching for community and facing existential loneliness, revealing some of the challenges of being a family in which one member is dying. 6. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We wish to thank the study participants for generously sharing their experiences. The authors received financial support for the research project from the Erling-Persson Family Foundation and the Signhild Engkvist Foundation. REFERENCES [1] Ek, K., Ternestedt, B.M., Andershed, B. and Sahlberg- Blom, E. (2011) Shifting life rhythms: Couples’ stories about living together when one spouse has advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Journal of Pal- liative Care, 27, 189-197. [2] Ekwall, E., Ternestedt, B.M. and Sorbe, B. (2007) Re- currence of ovarian cancer-living in limbo. Cancer Nursing, 30, 270-277. [3] Schumacher, K.L. and Meleis, A.I. (1994) Transitions: A central concept in nursing. Image: The Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 26, 119-127. doi: 10 .1111/j. 1547 -5069.1994.tb00929.x [4] Williams, A.M. (2004) Shaping the practice of home care: Critical case studies of the significance of the meaning of home. International Journal of Palliative Nursing, 10, 333-342. [5] Gomes, B., Calanzani, N., Curiale, V., McCrone, P. and Higginson, I.J. (2013) Effectiveness and cost-effective- ness of home palliative care services for adults with advanced illness and their caregivers. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 6, Article ID: CD007760. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007760.pub2 [6] Carlsson, M.E. (2012) Sleep disturbance in relatives of palliative patients cared for at home. Palliative & Sup- portive Care, 10, 165-170. doi:10.1017/S1478951511000836 [7] Stajduhar, K., Funk, L., Toye, C., Grande, G., Aoun, S. and Todd, C. (2010) Part 1: Home-based family care- giving at the end of life: A comprehensive review of published quantitative research (1998-2008). Palliative Medicine, 24, 573-593. doi:10.1177/0269216310371412 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  I. Carlander et al. / Open Journal of Nursing 3 (2013) 379-388 387 [8] Funk, L., Stajduhar, K., Toye, C., Aoun, S., Grande, G. and Todd, C. (2010) Part 2: Home-based family care- giving at the end of life: A comprehensive review of published qualitative research (1998-2008). Palliative Medicine, 24, 594-607. doi:10.1177/0269216310371411 [9] Andershed, B. (2006) Relatives in end-of-life care—Part 1: A systematic review of the literature the five last years, January 1999-February 2004. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 15, 1158-1169. d oi:10 .1111 /j.1365 -2702.2006.01473.x [10] Henriksson, A. and Andershed, B. (2007) A support group programme for relatives during the late palliative phase. International Journal of Palliative Nursing, 13, 175-183. [11] Wells, J.N., Cagle, C.S., Bradley, P. and Barnes, D.M. (2008) Voices of Mexican American caregivers for family members with cancer: On becoming stronger. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 19, 223-233. doi:10.1177/1043659608317096 [12] Hudson, P. (2004) Positive aspects and challenges associated with caring for a dying relative at home. International Journal of Palliative Nursing , 10, 58-65 [13] Anderson, B.A. and Kralik, D. (2008) Palliative care at home: Carers and medication management. Palliative & Supportive Care, 6, 349-356. doi:10.1017/S1478951508000552 [14] Carlander, I., Sahlberg-Blom, E., Hellstrom, I. and Ter- nestedt, B.M. (2011) The modified self: Family care- givers’ experiences of caring for a dying family member at home. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 20, 1097-1105. doi: 10 .1111/j. 1365 -2702.2010.03331.x [15] Jaspers, K. (1970) Philosophy. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago. [16] Chochinov, H.M. and Cann, B.J. (2005) Interventions to enhance the spiritual aspects of dying. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 8, S103-S115. doi:10.1089/jpm.2005.8.s-103 [17] Bryson, K.A. (2004) Spirituality, meaning, and trans- cendence. Palliative & Supportive Care, 2, 321-328. doi:10.1017/S1478951504040428 [18] Williams, A.L. (2006) Perspectives on spirituality at the end of life: A meta-summary. Palliative & Supportive Care, 4, 407-417. doi:10.1017/S1478951506060500 [19] Browall, M., Melin-Johansson, C., Strang, S., Danielson, E. and Henoch, I. (2010) Health care staff’s opinions about existential issues among patients with cancer. Palliative & Supportive Care, 8, 59-68. doi:10.1017/S147895150999071X [20] Koffman, J., Morgan, M., Edmonds, P., Speck, P. and Higginson, I.J. (2012) “The greatest thing in the world is the family”: The meaning of social support among black Caribbean and white British patients living with advanced cancer. Psycho-Oncology, 21, 400-408. doi:10.1002/pon.1912 [21] Arnold, B.L. (2011) Mapping hospice patients’ perception and verbal communication of end-of-life needs: An exploratory mixed methods inquiry. BMC Palliative Care, 10, 1. doi:10.1186/1472-684X-10-1 [22] Carlander, I., Ternestedt, B.M., Sahlberg-Blom, E., Hel- lström, I. and Sandberg, J. (2010) Being me and being us in a family living close to death at home. Qualitative Health Research , 21, 683-695. [23] Jo, S., Brazil, K., Lohfeld, L. and Willison, K. (2007) Caregiving at the end of life: Perspectives from spousal caregivers and care recipients. Palliative & Supportive Care, 5, 11-17. doi:10.1017/S1478951507070034 [24] Kristjanson, L.J. and Aoun, S. (2004) Palliative care for families: Remembering the hidden patients. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 49, 359-365. [25] Carlander, I., Ternestedt, B.M., Sahlberg-Blom, E., Hellstrom, I. and Sandberg, J. (2011) Being me and being us in a family living close to death at home. Qualitative Health Research , 21, 683-695. doi:10.1177/1049732310396102 [26] Pickens, N.D., O’Reilly, K.R. and Sharp, K.C. (2010) Holding on to normalcy and overshadowed needs: Family caregiving at end of life. Canadian Journal of Occu- pational Therapy, 77, 234-240. [27] Erikson, H. (1998) Life cycle completed. Extended ver- sion with new chapters on the ninth stage of development by Joan M. Erikson. W.W. Norton & Company, New York. [28] Midtgaard, J., Rorth, M., Stelter, R. and Adamsen, L. (2006) The group matters: An explorative study of group cohesion and quality of life in cancer patients par- ticipating in physical exercise intervention during treat- ment. European Journal of Cancer Care, 15, 25-33. [29] Stoltz, P., Lindholm, M., Uden, G. and Willman, A. (2006) The meaning of being supportive for family care- givers as narrated by registered nurses working in pal- liative homecare. Nursing Science Quarterly, 19, 163- 173. [30] Avis, M., Elkan, R., Patel, S., Walker, B.A., Ankti, N. and Bell, C. (2008) Ethnicity and participation in cancer self-help groups. Psychooncology, 17, 940-947. doi:10.1002/pon.1284 [31] Kurz, J.M. (2001) Experiences of well spouses after lung transplantation. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 34, 493- 500. [32] Milberg, A. and Strang, P. (2007) What to do when “there is nothing more to do”? A study within a salu- togenic framework of family members’ experience of palliative home care staff. Psycho-Oncology, 16, 741-751. doi:10.1002/pon.1124 [33] Brannstrom, M., Ekman, I., Boman, K. and Strandberg, G. (2007) Narratives of a man with severe chronic heart failure and his wife in palliative advanced home care over a 4.5-year period. Contemporary Nurse, 27, 10-22. [34] Palm, I. and Friedrichsen, M. (2008) The lived experience of closeness in partners of cancer patients in the home care setting. International Journal of Palliative Nursing, 14, 6-13. [35] Sand, L. and Strang, P. (2006) Existential loneliness in a palliative home care setting. Journal of Palliative Me- dicine, 9, 1376-1387. doi:10.1089/jpm.2006.9.1376 [36] Milberg, A. and Strang, P. (2004) Exploring compre- hensibility and manageability in palliative home care: An Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  I. Carlander et al. / Open Journal of Nursing 3 (2013) 379-388 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 388 OPEN ACCESS interview study of dying cancer patients’ informal carers. Psycho-Oncology, 13, 605-618. doi:10.1002/pon.774 [37] Dale, B., Saevareid, H.I., Kirkevold, M. and Soderhamn, O. (2010) Older home nursing patients’ perception of social provisions and received care. Scandinavian Jour- nal of Caring Sciences, 24, 523-532. [38] Nilsson, B., Lindstrom, U.A. and Naden, D. (2006) Is loneliness a psychological dysfunction? A literary study of the phenomenon of loneliness. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 20, 93-101. [39] Thorne, S. (1994) Secondary analysis in qualitative research: Issues and implications. Critical issues in qua- litative research methods. Sage, Thousand Oaks. [40] Thorne, S. (1998) Ethical and representational issues in qualitative secondary analysis. Qualitative Health Re- search, 8, 547-555. doi:10.1177/104973239800800408 [41] McAdams, D., Josselson, R. and Lieblich, A. (2006) Identity and story: Creating self in narrative. American Psychological Association, Washington DC. doi:10.1037/11414-000 [42] Thorne, S. (2008) Interpretive description. Left Coast Press, Walnut Creek. [43] Thorne, S., Kirkham, S.R. and MacDonald-Emes, J. (1997) Interpretive description: A noncategorical quali- tative alternative for developing nursing knowledge. Research in Nursing & Health, 20, 169-177. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-240X(199704)20:2<169::AID-N UR9>3.0.CO;2-I [44] Thorne, S., Reimer, K.S. and O’Flynn-Magee, K. (2004) The analytical challenge in interpretive description. Inter- national Journal of Qualitative Methods, 3, 1-11. [45] Jenkins, R. (2008) Social identity. 3rd Edition, Routledge, New York. [46] Yalom, I. (1980) Existential psychotherapy. Basic Books, Inc., New York. [47] Waldrop, D.P., Kramer, B.J., Skretny, J.A., Milch, R.A. and Finn, W. (2005) Final transitions: Family caregiving at the end of life. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 8, pp. 623-638. doi:10.1089/jpm.2005.8.623 [48] Glaser, B.S. (1965) An awareness of dying. Aldine, New York. [49] Andrews, T. and Nathaniel, A.K. (2009) Awareness of dying revisited. Journal of Nursing Care Quality, 24, 189-193. [50] Grothe, T.T., Rydahl, H.S. and Wagner, L.I. (2012) Prioritising, downpalying and self-preservation: Pro- cessess significant to coping in advanced cancer patients. Open Journal of Nursing, 2, 48-57. doi:10.4236/ojn.2012.22009 [51] Meleis, A.I. (2010) Theoretical development of tran- sistions. In: Meleis, A.I., Ed., Transition Theory Middle- range and Situation-Specific Theories in Nursing Re- search and Practice, Springer Publishing Company, New York, 13-51. [52] Andershed, B. and Ternestedt, B.M. (2001) Development of a theoretical framework describing relatives’ invol- vement in palliative care. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 34, 554-562. [53] Ward-Griffin, C. and McKeever, P. (2000) Relationships between nurses and family caregivers: Partners in care? Advances in Nursing Science, 22, 89-103. [54] Sahlberg-Blom, E., Ternestedt, B.M. and Johansson, J.E. (2000) Patient participation in decision making at the end of life as seen by a close relative. Nursing Ethics, 7, 296- 313. [55] Milberg, A. and Strang, P. (2003) Meaningfulness in palliative home care: An interview study of dying cancer patients’ next of kin. Palliative & Supportive Care, 1, 171-180. doi:10.1017/S1478951503030311 [56] Dean, R.A. and Gregory, D.M. (2004) Humor and lau- ghter in palliative care: An ethnographic investigation. Palliative & Supportive Care, 2, 139-148. doi:10.1017/S1478951504040192 [57] Astedt-Kurki, P. and Isola, A. (2001) Humour between nurse and patient, and among staff: Analysis of nurses’ diaries. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 35, 452-458. [58] Dean, R.A. and Gregory, D.M. (2005) More than trivial: Strategies for using humor in palliative care. Cancer Nursing, 28, 292-300. [59] Hollman, G., Ek, A.C., Olsson, A.G. and Bertero, C. (2004) Meaning of quality of life among patients with familial hypercholesterolemia. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 19, 243-250. doi:10.1097/00005082-200407000-00004 [60] Kirk, P., Kirk, I. and Kristjanson, L.J. (2004) What do patients receiving palliative care for cancer and their families want to be told? A Canadian and Australian qualitative study. British Medical Journal, 328, 1343. [61] Benzar, E., Hansen, L., Kneitel, A.W. and Fromme, E.K. (2011) Discharge planning for palliative care patients: A qualitative analysis. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 14, 65-69. doi:10.1089/jpm.2010.0335 [62] Sahlberg-Blom, E., Ternestedt, B.M. and Johansson, J.E. (2001) Is good “quality of life” possible at the end of life? An explorative study of the experiences of a group of cancer patients in two different care cultures. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 10, 550-562. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2702.2001.00511.x [63] Thorne, S. (1994) Secondary analysis in qualitative re- search: Issues and implications. In: Morse, J., Ed., Criti- cal Issues in Qualitative Research Methods, Sage, Thou- sand Oaks, pp. 263-279.

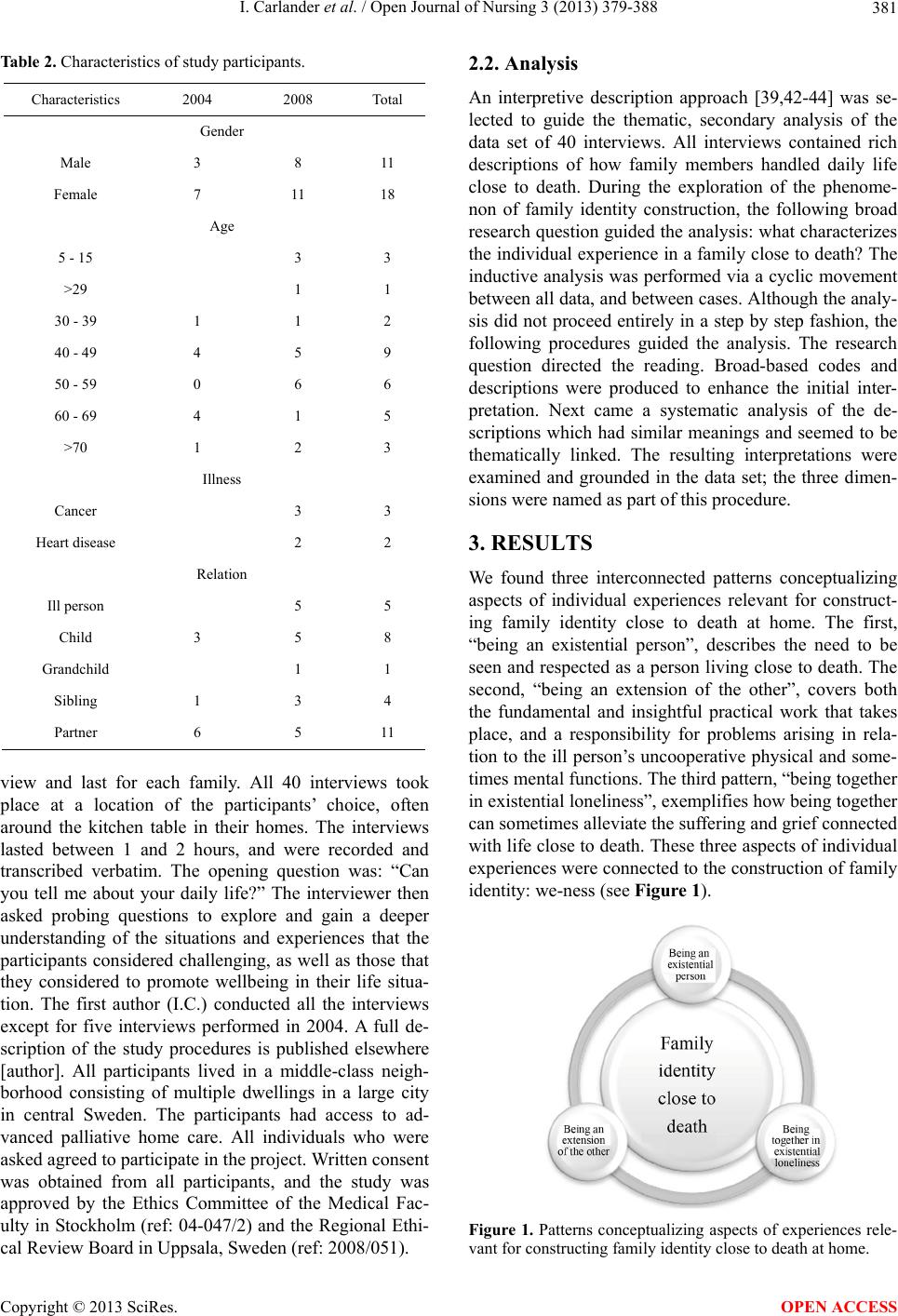

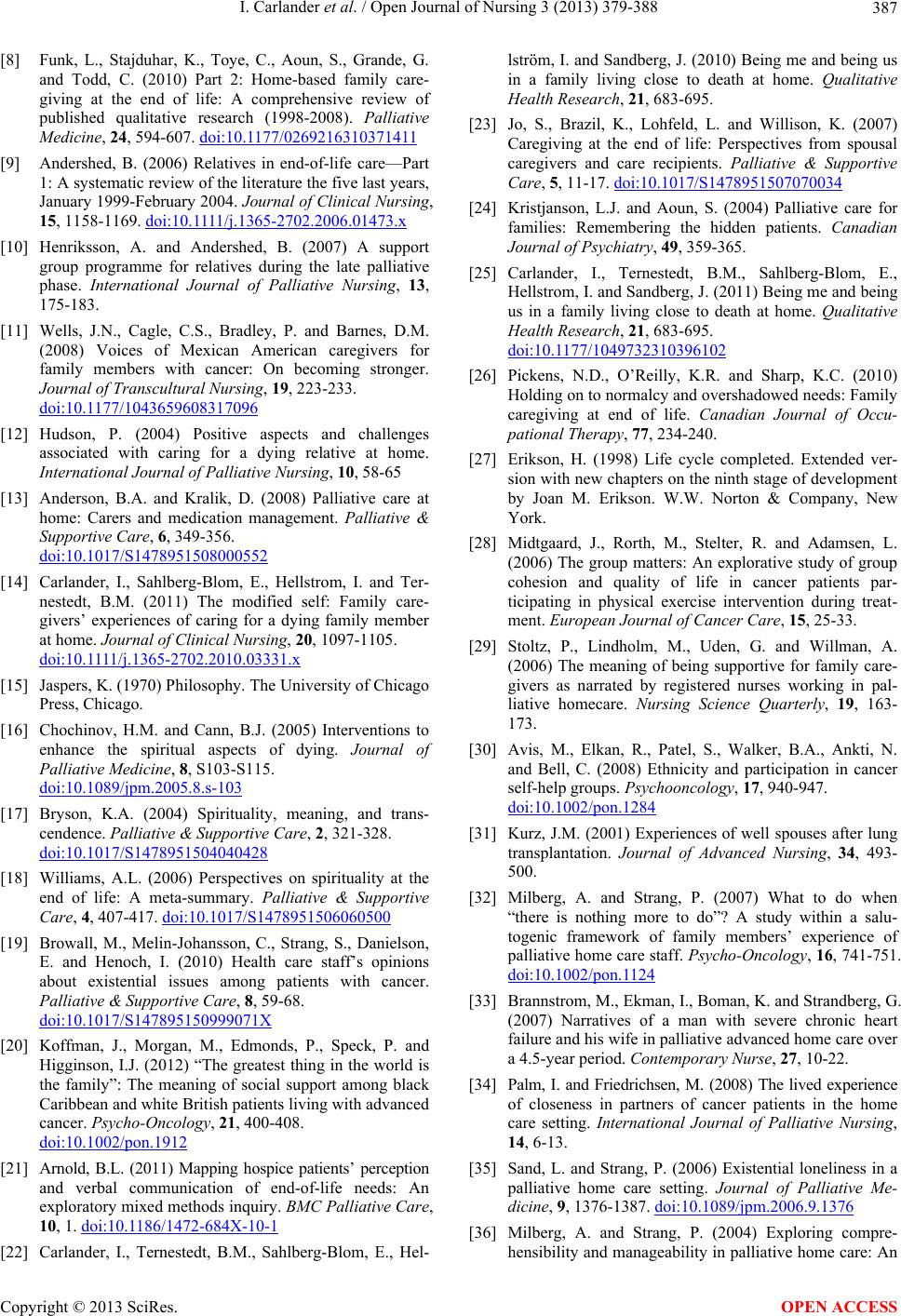

|