Open Journal of Psychiatry, 2013, 3, 329-334 OJPsych http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojpsych.2013.33034 Published Online July 2013 (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ojpsych/) Clinical and therapeutic implications of psychiatric comorbidity in high functioning autism/Asperger syndrome: An Italian study Silvia Giovinazzo1, Sara Marciano1, Graz ia Giana2, Paolo Curatolo1, Maria-Cristina Porfirio1 1Department of Child Neurology and Psychiatry, Tor Vergata University, Rome, Italy 2Department of Neuroscience, Child and Adolescence Psychiatry Unit, Children Hospital Bambino Gesù, Rome, Italy Email: silviagiovinazzo@yahoo.it Received 10 March 2013; revised 12 April 2013; accepted 20 April 2013 Copyright © 2013 Silvia Giovinazzo et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. ABSTRACT The present study describes the occurrence of psychi- atric comorbid disorders in a cohort of 86 high func- tioning autism (HFA)/Asperger syndrome (AS) pa- tients, examined at Child Neurology and Psychiatry Unit of Tor Vergata University. 38 patients out of 86 (44.2%) presented one or more psychiatric comorbid- ities, such as mood disorders, Attention Deficit/Hy- peractivity Disorder (ADHD), Tourette syndrome (TS), anxiety disorders, including obsessive-compul- sive disorder (OCD), and psychotic symptoms. We compared our sample with the evidences from the scientific literature on psychiatric comorbidity in ASD patient, in particular in HFA/AS. In this paper we focu s on the high frequency of comorbid psy chiat- ric disorders in HFA/AS patients, such as mood dis- orders, Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), Tourette syndrome (TS), anxiety disorders, including obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and psychosis, including schizophrenia. We analyzed rates of all psichiatric comorbidities diagnosed in a sample of HFA/AS subjects and we compared findings from our study with the evidences from the scientific lit- erature on psychiatric comorbidity in ASD patients, in particular HFA/AS. We point out that comorbid psychiatric symptoms can be hardly diagnosed, be- cause they could present atipically in ASDs then in general population. Furthermore, they could be mask- ed by ASD core symptoms. Keywords: Autistic Spectrum Disorders; Psychiatric Comorbidity 1. BACKGROUNDS Despite of the increased knowledge about the pathoge- netic mechanisms and an improvement of the diagnostic criteria, clinical practitioners have a really poor under- standing that Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASDs) occur most frequently than thought in general population (prevalence rate for all ASD is estimated at 1%) [1]. ASDs are neurobiological disorders, caused by complex gene-environment interactions, not yet fully identified [2]. Several studies on patients with ASDs indicate that up to 70.8% of them are affected by one or more psychiatric condition in comorbidity [3]. Psychiatric comorbidity occurs highly in patients with High Functioning Autism (HFA) and Asperger syndrome (AS) [4-6], which are milder forms of autism, according to some authors. HFA individuals have a good cognitive level, expressed by an IQ > 70. AS is characterized by high verbal IQ, impaired social interaction, restricted interests and ritualistic be- haviours, in absence of language delay. It is still debated if a comorbid d isorder could occur in ASD patients with a range of different symptoms from those on es that ar e pathognomon ic in g eneral popu lation. The identification of psychiatric comorbidity is difficult in ASD patients: any psychiatric symptoms could overlap with or be masked by ASD symptoms themselv es. In this regard, HFA/AS patients could provide clinical information about their emotional states, due to their high cognitive level and great verbal communication. Moreover, those characteristics allow them to attend mainstream school and so they often experience more bullying and less social support, which seem to be re- lated to increasing psychiatric comorbidities, like con- duct problems and disruptive behavi o rs [ 1] . On the other hand, it was found that ASDs are much less recognized and diagnosed in those with milder core symptoms. HFA/AS patients may therefore present to health services for other psychiatric symptoms and these OPEN ACCESS  S. Giovinazzo et al. / Open Journal of Psychiatry 3 (2013) 329-334 330 surface features may not clearly signal the presence of an ASD [1]. According to DSM-IV-TR [7], ADHD, OCD, schizo- phrenia are excluded from ASD diagnostic criteria and diagnosis of anxiety disorders is to be avoided. But many people with ASD also have a range of psychiatric symp- toms quite corresponding to diagnostic criteria for those psychiatric dis order s. Furthermore, according new DSM-V diagnostic crite- ria, AS will not be provided for in ASDs. Nevertheless, we led our study while DSM-IV-TR criteria were still valid and we could recruit AS patients. However, both our and the other findings about psychiatric comorbidity in AS, hereafter should alert clinicians abou t the high risk of psychopathology in an “AS-like” people, although it can no longer be considered as “autistic” people. Have not yet been identified specific risk factors for the development of co-morbidity in ASDs. Risk factors that are well recognized in general popu lation to be asso- ciated with child psych iatric disorders show similar rela- tionship in children with ASDs [1]. It has been demo- strated that individuals with less severe ASDs, as HFA and AS, are equally likely to show additional psychiat- ric disorders [1]. Frequently are diagnosed anxiety and depression, be- havioral disorders like ADHD or oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) and obsessive disorders [2,8,9]. Some studies report rare cases of comorbidity with schizophre- nia and other disorders, including Tourette’s syndrome, tics, trichotillomania, enuresis or encopresis. Many pa- tients present multiple comorbid disorders: respectively 80% of ASDs plus ADH D, 60% of ASD s plus behavi oral disorder, 40% of ASDs plus affective disorder have an- other or more comorbidities [3]. 2. CLINICAL STUDY 2.1. Objectives Our clinical study aimed to: Describe the psychiatric comorbid disorders in a co- hort of HFA/AS patie nt s; Define the prevalence of every psychiatric conditio ns in the sample, comparing our data with the literature; Identify how many comorbid psychiatric conditions have arisen in each patient; Identify a possible relationship between age of pa- tients and the develop ment of a specific comorbidity; Assess the drugs used for the treatment of psychiatric symptoms, defining how many patients needed to set up a polytherapy. 2.2. Methods and Materials The sample consisted of 86 HFA/AS patients, examined at Child Neurology and Psychiatry Unit of Tor Vergata University, in Rome, from 2009 to 2012. The patient’s mean age was 14.9 years (median 13.1, SD 6.7), with a mean age at evaluation of 11.9 years (SD 7.1). Male patients were 77 out of 86 (89%), with a male/ female ratio of 8.5. Autistic symptoms were assessed by comparing the core clinical features with the DSM-IV diagnostic crite- ria for ASDs; furthermore, the diagnosis of ASD was supported by the Autism Diagnostic Observation Sched- ule (ADOS; Lord et al., 2000) and the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revi sed (A D I -R ; L or d et al ., 1995). Cognitive assessment was performed by the Wechsler Intelligence Scales (WISC-III; Wechsler, 1991) and non verbal Leiter International Performance Scale-Revised (Leiter-R-Visualization and Reasoning, Roid & Miller, 1997). The presence of psychiatric disorders in comorbidity was evaluated by: Kiddie-Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizo- phrenia (K-SADS; Kaufman et al., 1997), a semi- structured interview designed to assess present and past episodes of psychiatric disorders in children and adolescents between the ages of 6 - 18, according to DSM-IV criteria; Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) 4/18 years, a ques- tionnaire completed by parents, about children/ado- lescent behavioral (e.g. internalizing problems-with- drawal, somatic complaints, anxiety/depression-, de- linquent behavior and externalizing behavior aggres- sive and also attention difficulties, social problems and thought prob lems); Conners’ Parent and Conners’ Teacher Rating Scale, which are questionnaires filled by parents or teachers, which provide to assess an d quantify oppositional be- havior, inattention, hyperactivity and ADHD Index; Swanson, Nolan, and Pelham-IV (SNAP-IV), a ques- tionnaire designed to assist in diagnosing a child’s behavioral problems, like Attention Deficit Disorder with Hyperactivity (ADHD) and Oppositional Defi- ant Disorder; Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI), a brief self- report test that assesses signs of depression in chil- dren and adolescents 7 to 17 years old; Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC), a self-report test that assesses the presence of symp- toms related to anxiety disorders in youth aged 8 to 19 years. 2.3. Results In our sample, all 86 subjects were high functioning, with full scale IQ > 70. Mean IQ was 92.4 (SD = 20.9). Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  S. Giovinazzo et al. / Open Journal of Psychiatry 3 (2013) 329-334 331 38 patients out of 86 (44.2%) had one or more psy- chiatric comorbidities. Attention deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) was the most common comorbidity, diagnosed in 25 patients (66%). Were also diagnosed bipolar disorder (n = 7; 18.4%), depression (n = 2; 5.3%), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) (n = 2; 5.3%), positive psychotic symptoms (n = 6; 15.8%), learning disorder (n = 1; 2.6%), obsessive- compulsive disorder (n = 1; 2.6%), eating disorders (n = 1; 2.6%), oppositional defiant disorder (n = 2; 5.3%), tics and Tourette’s syndrome (n = 2; 5.3%) (Table 1). These 38 patients was divided in 3 groups: 1) only with one comorbidity (71%), 2) with 2 comorbidity (24%), 39 with 3 or more (5%) (Table 2). The association between ADHD and Bipolar Disorder occurred most frequently in patients with multiple comorbidities (36.4%). We studied the distribu tion of comorbidities with in the sample (Table 3), according to four age ranges: Childhood, including 6- to 8-year and 11 months-old: n = 7 (18.4% ); Pre-puberty: including 9- to 13-year and 11 months- old subjects: n = 9 ( 23.7%); Adolescence, including 14- to 17-year and 11 months- old subjects: n = 11 (28. 9%); Adulthood, including 18 years-old subjects and over: n = 11 (28 .9%). There was a higher incidence of comorbidity in ado- lescence. The prevalence of multiple comorbidities in- Table 1. Comorbid disorders diagnosed in our sample. Comorbid Disorder Rate of patients (%) Attention deficit/Hyperactivity disorder 66 Bipolar disorder 18.4 Psychosis 15.8 Depression 5.3 Tics and Tourette’s synd rome 5.3 Generalized anxiety disorder 5.3 Oppositional defiant disorder 5.3 Eating disorder 2.6 Obsessive/Compulsive disorder 2.6 Learning disorder 2.6 Table 2. Rate of patients presenting one or more psychiatric comorbidities. Comorbid psychiatric disorder Rate of patients (%) Any psychiatric disorder 44.2% One psychiatric disorder 71% Two psychiatric disorder 24% Three or more psychiatric disorder5% Table 3. Distribution of comorbidities within our sample, according to age ranges. Age ranges Comorbidity [6,9] ys 18.4% [9,14] ys 23.7% [14,18] ys 28.9% >18 ys 28.9% Attention deficit/Hyperact ivity disorder X X X X Bipolar disorder X X X Psychosis X X Depression X Tics and Tourette’s syndromeX X Generalized anxiety disorder X X X Oppositional defiant disorder X X Eating disorder X Obsessive/Compulsive disorder X Learning disorder X creased in puberty and in adolescence. Every age range was characterized by suffering from specific types of comorbidity. Of the 38 patients with comorbidities, 19 (50%) re- ceived pharmacological treatment. Regarding disrup- tive behaviours, most of our ASD plus ADHD patients responded to MPH, one patient did not tolerate that drug and had to change with atomoxetine, and another patient was treated only with atomoxetine. The patients with ODD also were treated with methylphenidate. Psychotic symptoms were treated with atyical antipy- chotics, as well as olanzapine or risperidone in most cases, or aripiprazole in a single case. The patient with GAD received treatment with par- oxetine (SSRI) and OCD was treated with sertraline (SSRI). The patients with depressive disorder received benzo- diazepines or venlafaxine (NSRI) and that with BD re- ceived Valproic Acid, which is the first line treatment for BD in youth. The case of eating disorders was treated with mirtazapine (NARI). 74% of the cases received a polypharmacotherapy. 3. DISCUSSION We compared findings from our study with the evidences from the scientific literature on psychiatric comorbidity in individuals with ASD. We consider at first the only population-study d ealing with several psychiatric co mor- bidities in ASD subject, involving a population-derived sample. We found that 44.2% of our HFA/AS patients had co- morbid psychiatric disorders. Our results differ from the study of Simonoff et al. [3]: they found that 70.8% of 112 ASD patients had at least one psychiatric comorbid- ity. However, that sample also included patients with Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  S. Giovinazzo et al. / Open Journal of Psychiatry 3 (2013) 329-334 332 low-functioning autism, which are more frequently and severely affected by psychiatric symptoms, as well as disruptive or repetitive behaviours, aggression, irritabil- ity [5]. Moreover, they employed more effective diag- nostic tools for screening and diagnosis of psychiatric disorders in ASD, like Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment (CAPA; A ngold and Costello, 2000). In 2009, Mukkades et al. [4] pointed out a >90% prevalence of comorbidity in AS and HFA samples: the high rate was probably due to referral bias in diagnostic process. In 2010, Mattila et al. [5] conducted a study on com- bined community- and clinic-sample of HFA/AS pa- tients, aged from 9.8 to 16.3 years. They highlighted a comorbidity prevalence of 74%, in a cohort aged more restrictely than ours. We considered also the age corre- lated with the comorbidity. This correlation is low and this aspect influenced th e global prevalen ce in our popu- lation. In our sample, 31% of patients had multiple comorbid- ities, as compared to 33% reported by Simonoff et al. [3], and to 37% by Mattila et al. [5]. The same comorbidities have been identified in these studies, as well as in ours: ADHD, GAD, OCD, ODD, eating behavior disorders, BD and depression, tics and TS, learning disorders and psychosis. This recurrent finding of the same associa- tions between disorders emphasizes that they have a common genetic and neurobiological substrate. In our sample, ADHD is the most frequent comorbid disorder (66%), specially presenting in childhood and puberty. In literature, the prevalence of ADHD among individuals with ASD is estimated to be 28.2% [3], particularly among those with HFA/AS it’s 44% - 65% [6]. These findings stress the clinical necessity to assess inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity in ASD [10], and point out also the fact that often is difficult to establish early diag- nosis of HFA/AS, because autistic symptoms could be masked by ADHD symptoms. The neurobiological point of view shows that ASD and ADHD are deficits in executive functioning and re- flect a common dysfunction of fronto-temporal circuits [11]. ASD and ADHD also share genetic background: some chromosomal regions such as 2q24, 16p13, 16p1, 17p11, 5p13, 15q have been identified as susceptibility loci to both ADHD and ASD [12]. Furthermore, two patients had oppositional defiant disorder (5.6%), compared to 1% in the study of Simon- off, to 16% according to Mattila et al. [5], up to 30% according Mukkades et al. [4]. Must be considered that aggression, often found in ODD, is common in ASD pa- tients, most of all in LFA; moreover, could be the epiphenomenon of other types of comorbidity, e.g. mood disorders or anxiety [5]. Bipolar disorder occurred in 5.2% of cases, specially in adolescence, as well as other mood disorders. These data are in accord to the literatu re [13-16] (prevalence of 2% - 9%, usually in adolescence). Depression occurred in 5.2%, with onset in adulthood, compared with 0.9% evidenced by Simonoff [3]. De- pression can often arise with an increase of withdrawal and aggressive behaviours: these symptoms may present more clearly in patients with HFA/AS, rather than in low-functioning autism (LFA), which could primarily presenting withdrawal and aggression. From other stud- ies has been reported a very broad range of prevalence of mood disorders, from 6% up to 70% [4,5,15-19]. This variability could depend to the fact that some authors examined only AS patients, other ones considered de- pressive symptoms rather then a diagnosis of major de- pression. Only one adolescent patient presented OCD and two individuals had a GAD (5.26%), one at puberty, the other at about 18 years. Simonoff et al. [3] found that 2% of ASD patients developed a OCD and up to 44% an anxi- ety disorders. According to the literature, OCD is the anxiety disorder that appears most frequently in ASD [3,20,21]. It is possible to recognize obsessions/compulsions from ASD repetitive behaviours, [6], but standardized diagnostic tools are currently no t yet available. In our sample, 15.8% of patients presented psychotic symptoms, with onset in adulthood. In literature, the prevalence of schizophrenia in ASD is of 0.6% [11], in HFA/AS up to 3.3% [4]. In adults with schizophrenia, there is often a h istory of autistic sympto ms in childhood; autism and schizophrenia share some neurobiological abnormalities and genetic back grounds [17,18]. According to all literature examined [3], tics and Tourette’s syndrome had an overall prevalence of 22% - 30% [4,5,6,22]. Indeed, TS is considered a risk factor for development of further neuropsychiatric disorder, in ASD subjects [22, 23]. In our sample, two individuals presented tics only as comorbidity. About pharmacoterapy in ASDs [24], atypical antipsy- chotics or neuroleptics can be effective against aggres- sion and core symptoms; but it is often necessary to ad- minister multiple drugs to control comorbid psychiatric symptoms. Methylphenidate is the first choice for the treatment of ADHD, benzodiazepines for anxiety symp- toms, SSRI’s for the treatment of OCD and mood disor- ders. This study has some limitations, at first by having a moderate sample size, a too wide age range and no com- parison group. The age-ranged groups were not well- matched in gender and number of patients. Second, the assessment by the parents and children/adolescents may have resulted in some recall and/or referral bias. Fur- thermore, we have not distinctly considered current psy- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  S. Giovinazzo et al. / Open Journal of Psychiatry 3 (2013) 329-334 333 chiatric diagnosis from past comorbidity. Third, the present study only provides the rate and type of psychiatric disorders, and there was no informa- tion provided regarding associated risk factors such as family history and life events. In addition, concerning the diagnostic instruments used in this study, there are no algorithms precisely for ASD. Regarding to the pharmacological treatment, it would be necessary to involve and monitorize a larger sample of treated patients, to verify its short and long term effi- cacy. 4. CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE PROSPECTIVES There is still no consensus about the belief that symp- toms of new onset in ASD should be classified as a manifestati on of furt her psychiatric disor der. It could be useful to assess the possible common pathogenetic mechanisms and risk factors between ASDs and other psychiatric disorders, and to obtain additional information on the underlying disfunction [25]. In literature there are only few data about comorbid psychiatric disorders in ASDs. It could be necessary to increase the sample size and to collect the largest number of clinical-anamnestic information, for studying etiopa- thogenesis and risk factors for the occurrence of comor- bidity [26,27]; meta-analysis studies would be useful, to compare individual researches. It would be interesting to highlight a possible correspondence between age and the development of a specific comorbid disease. This report may be useful for lifetime monitoring patients, to predict the onset of a specific disease, and for early recognition of symptoms, to plan a focused and effective treatment. According to some authors, there is need for caution in interpreting results that use generic measures in higlhy specific and distinct populations, as well as ASDs, with- out first characterizing the instrument properties, e.g. scoring and cut-offs, pertaining to that population [1]. Clinical practicioners should be able to use diagnostic tools which are specific for the diagnosis of comorbidity in ASD patients, to recognize atypical or masked symp- toms (e.g. Autism Comorbidity Interview Present and Lifetime version; ACI-PL; Lefeyer et al., 2006; Devel- opmental Disability Child Global Assessment Scale; DD- CGAS; Wagner et al., 2007). It would also be necessary to update the diagnostic criteria for psychiatric disorders most commonly associated with ASD, adapting them to the characteristics of these patients. REFERENCES [1] Simonoff, E., Jones, C.R., Baird, G., Pickles, A., Happé, F. and Charman, T. (2013) The persistence and stability of psychiatric problems in adolescents with autism spec- trum disorders. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 54, 186-194. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02606.x [2] Abrahams, B.S. and Geschwind, D.H. (2008) Advances in autism genetics: On the threshold of a new neurobiol- ogy. Nature Genetics, 9, 341-353. [3] Simonoff, E., Pickles, A., Charman, T., Chandler, S., Loucas, T. and Baird, G. (2008) Psychiatric disorders in children with autism spectrum disorders: Prevalence, comorbidity, and associated factors in a population-de- rived sample. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 47, 921-929. doi:10.1097/CHI.0b013e318179964f [4] Mukaddes, N.M., Hergüner S. and Tanidir, C. (2010) Psychiatric disorders in individuals with high-functioning autism and Asperger’s disorder: Similarities and differ- ences. World Journal of Biological Psychiatry, 11, 964- 971. doi:10.3109/15622975.2010.507785 [5] Mattila, M.L., Hurtig, T., Haapsamo, H., et al. (2010) Co- morbid psychiatric disorders associated with Asperger syndrome/high-functioning autism: A community- and clinic-based study. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40, 1080-1093. doi:10.1007/s10803-010-0958-2 [6] Mazzone, L., Ruta, L. and Reale, L. (2012) Psychiatric comorbidities in Asperger syndrome and high functioning autism: Diagnostic challenges. Annals of General Psychi- atry, 11, 16. [7] American Psychiatric Association (2000) Diagnostic and statical manual of mental disorders. 4th Edition, APA, Washington, DC. [8] Kim, J.A., Szatmari, P., Bryson, S.E., Streiner, D.L. and Wilson, F. (2000) The prevalence of Anxiety and mood problems among children with autism and Asperger syn- drome. Autism, 4, 117-132. doi:10.1177/1362361300004002002 [9] Gadow, K.D., DeVincent, C.J. and Schneider, J. (2009) Comparative study of children with ADHD only, autism spectrum disorder + ADHD, and chronic multiple tic dis- order + ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders, 12, 474-485. doi:10.1177/1087054708320404 [10] Yoshida, Y. and Uchiyama, T. (2004) The clinical neces- sity for assessing Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disor- der (ADHD) symptoms in children with high-functioning Pervasive Developmental Disorder (PDD). European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 13, 307-314. doi:10.1007/s00787-004-0391-1 [11] Sinzig, J., Morsch, D., Bruning, N., Schmidt, M.H. and Lehmkuhl, G. (2008) Inhibition, flexibility, working memory and planning in autism spectrum disorders with and without comorbid ADHD-symptoms. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 2, 4-15. doi:10.1186/1753-2000-2-4 [12] Rommelse N.N., Geurts H.M., Franke B., Buitelaar J.K., Hartman C.A. (2011) A review on cognitive and brain endophenotypes that may be common in autism spectrum disorder and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and facilitate the search for pleiotropic genes. Neuroscience Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  S. Giovinazzo et al. / Open Journal of Psychiatry 3 (2013) 329-334 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 334 OPEN ACCESS & Biobehavioral Reviews, 35, 1363-1396. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2011.02.015 [13] Raja, M. and Azzoni, A. (2008) Comorbidity of Asper- ger’s syndrome and Bipolar disorder. Clinical Practice and Epidemiology in Mental Health, 4, 26-31. doi:10.1186/1745-0179-4-26 [14] Munesue, T., Ono, Y., Mutoh, K., Shimoda, K., Nakatani, H. and Kikuchi, M. (2008) High prevalence of bipolar disorder comorbidity in adolescents and young adults with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder: A pre- liminary study of 44 outpatients. Journal of Affective Disorders, 111, 170-175. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2008.02.015 [15] Hofvander, B., Delorme, R., Chaste, P., Nydén, A., Wentz, E., Ståhlberg, O., et al. (2009) Psychiatric and psychosocial problems in adults with normal-intelligence autism spectrum disorders. BMC Psy chiatry, 10, 35. [16] Lugnegård, T., Hallerbäck, M.U. and Gillberg, C. (2011) Psychiatric comorbidity in young adults with a clinical diagnosis of Asperger syndrome. Research in Develop- mental Disabilities, 32, 1910-1917. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2011.03.025 [17] Rapoport, J., Chavez, A., Greenstein, D., Addington, A. and Gogtay, N. (2009) Autism-spectrum disorders and childhood onset schizophrenia: Clinical and biological contributions to a relationship revisited. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 48, 10-18. doi:10.1097/CHI.0b013e31818b1c63 [18] Stahlberg, O., Soderstrom, H., Rastam, M. and Gillberg, C. (2004) Bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and other psychotic disorders in adults with childhood onset AD/hd and/or autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Neural Transmission, 111, 891-902. doi:10.1007/s00702-004-0115-1 [19] Ghaziuddin, M., Ghaziuddin, N. and Greden, J. (2002) Depression in persons with autism: Implications for re- search and clinical care. Journal of Autism and Deve- lopmental Disorders, 32, 299-306. doi:10.1023/A:1016330802348 [20] Russel, A.J., Mataix-Cols, D., Anson, M. and Murphy, D.G.M. (2005) Obsessions and compulsions in Asperger syndrome and high-functioning autism. British Journal of Psychiatry, 186, 525-528. doi:10.1192/bjp.186.6.525 [21] Ruta, L., Mugno, R., Genitori, D’Arrigo, V., Vitiello, B. and Mazzone, L. (2008) Obsessive-compulsive traits in children and adolescents with Asperger syndrome. Euro- pean Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 19, 17-24. doi:10.1007/s00787-009-0035-6 [22] Burd, L., Li, Q., Kerbeshian, J., Klug, M. G. and Freema n, R.D. (2009) Tourette syndrome and comorbid pervasive developmental disorders. Journal of Child Neurology, 24, 170-175. doi:10.1177/0883073808322666 [23] Canitano, R. and Vivanti, G. (2007) Tics and Tourette syndrome in autism spectrum disorders. Autism, 11, 19- 28. doi:10.1177/1362361307070992 [24] Benvenuto, A., Battan, B., Porfirio, M.C. and Curatolo, P. (2013) Pharmacotherapy of autism spectrum disorders. Brain & Development, 35, 119-127. doi:10.1016/j.braindev.2012.03.015 [25] Gadow, K.D., Roohi, J., DeVincent, C.J. and Hacthwell, E. (2008) Association of ADHD, tics, and anxiety with dopamine transporter (DAT1) genotype in autism spec- trum disorder. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychia- try, 49, 1331-1338. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01952.x [26] Kanne, S.M., Abbacchi, A.M. and Constantino, J.N. (2009) Multi-informant ratings of psychiatric symptom severity in children with autism spectrum disorders: The importance of environmental context. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 39, 856-864. doi:10.1007/s10803-009-0694-7 [27] Hurtig, T., Kuusikko, S., Mattila, M.L., et al. (2009) Mul- ti-informant reports of psychiatric symptoms among high-functioning adolescents with Asperger syndrome or autism. Autism, 13, 583-598. doi:10.1177/1362361309335719

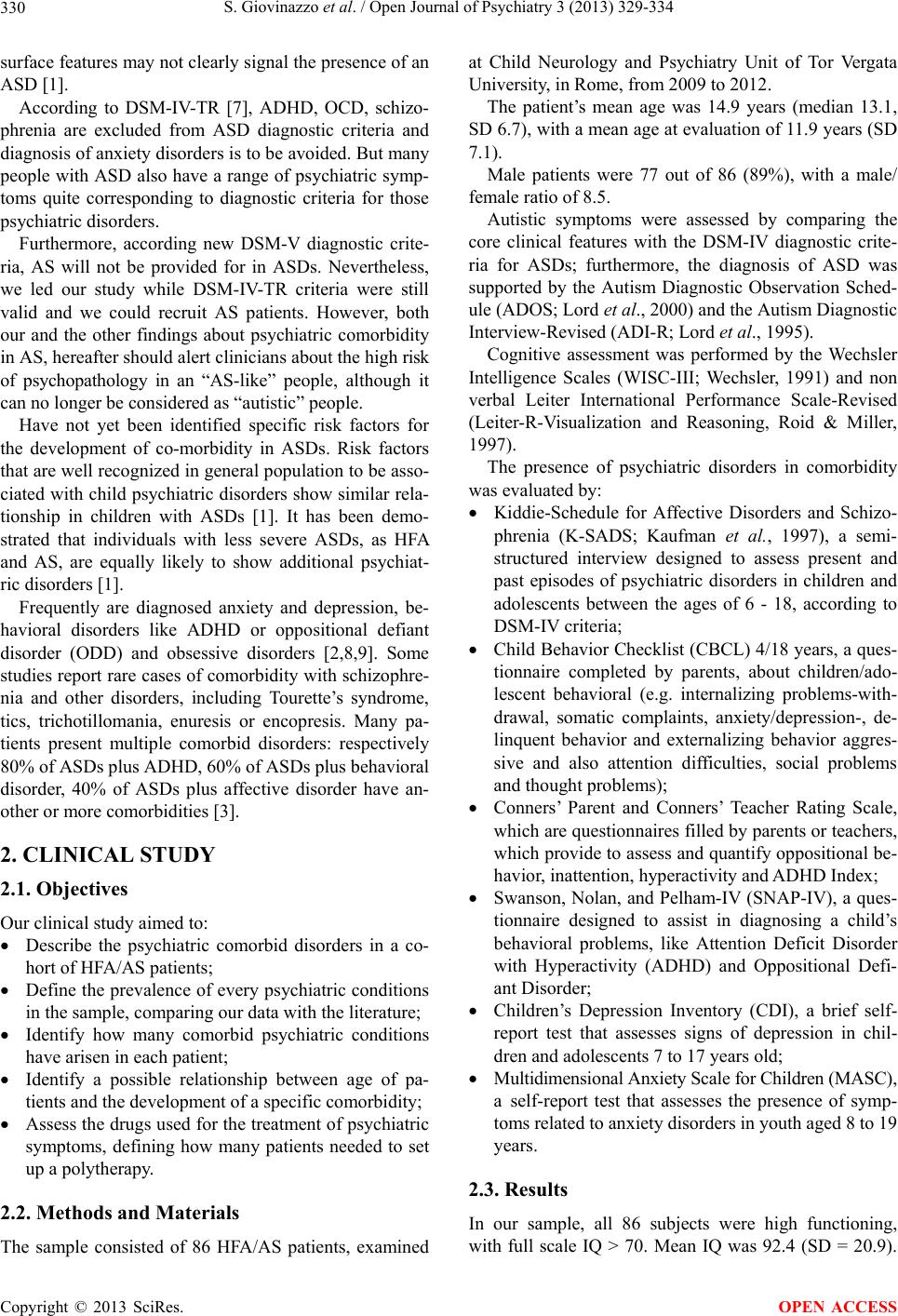

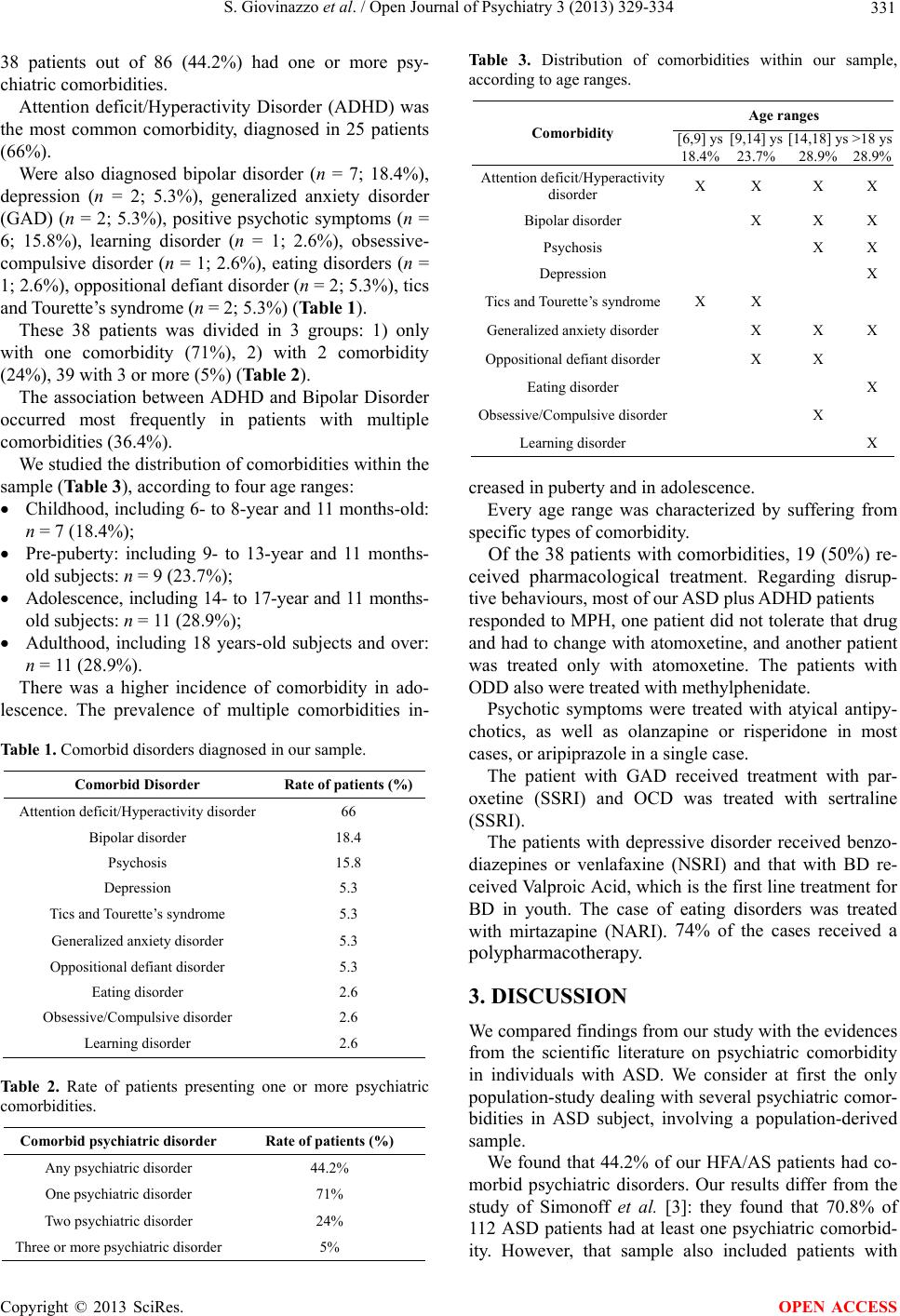

|