Open Journal of Leadership 2013. Vol.2, No.2, 36-44 Published Online June 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ojl) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojl.2013.22005 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 36 The Organizational Culture Audit: Countering Cultural Ambiguity in the Service Context Mark R. Testa, Lori J. Sipe San Diego State University, San Diego, USA Email: mtesta@mail.sdsu.edu, lsipe@mail.sdsu.edu Received January 11th, 2013; revise d Fe bruary 7th, 2013; acce pted May 10th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Mark R. Testa, Lori J. Sipe. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the origina l w o rk is properly cited. Development of a compelling organizational culture continues to be an imperative for organizations seeking a competitive advantage. Identifying culture deficiencies or gaps is an important step in creating such a culture. For culture development efforts to be successful, leaders must first know the reality of the current organizational culture, however assessing the organizations’ true culture may be more compli- cated than it appears. Several theoretical frameworks illustrate how highly committed mangers may have difficulty in this regard. The following study links theory with application providing an action research based model of culture assessment. First, the rationale and conceptual model of cultural analysis is pro- vided based on past research. Next, a five-step model analyzing ten cultural areas is proposed, and rec- ommendations are provided for implementation. Keywords: Organizational Culture; Leadership; Culture Assessment; Gap Analysis Introduction As competition increases and customers become more demanding, organizational leaders are faced with the di- lemma of creating a sustainable competitive advantage. One method of developing su ch an adva ntage is to actively build a compelling organizational culture. This may particularly true in organizations where stakeholders deal directly with cus- tomers. This is well known by leading organizations with rich organizational cultures such as Southwest Airlines, Star- bucks and Ritz Carlton, a nd is supported by some forty years of research (Schein, 1992). Whether termed “corporate” or “organizational” culture, the construct has become a main- stay variable in investigations of organizational development (Leidner & Kayworth, 2006; Sche in, 2004; T refry, 2006). Past studies have looked extensively at the relationship between culture and important organizational variables in- cluding organizati onal performance (Kotter & Heske tt, 1992; LeBlanc & Mills, 1995; Xenikou & Simosi, 2006), effec- tiveness (Denison & Mishra, 1995; Kemp & Dwyer, 2001), and profitability (Tidball, 1988). In organizations that pro- vide services, customer perceptions are critical for success and culture may be an even more important variable as it has been linked to work-related attitudes (Bim baum & Sommers, 1986), and can influence individu al and group behavior (Tre- fry, 2006). In the service setting, leaders do not have direct control over customer perceptions of quality or employee behavior (Ueno, 2010). Consequently, creating a compelling service-oriented culture may be one of the few organization influence tactics available for senior mana gers. In spite of the importance of an organization’s culture on essential outcomes, disconnects between the desired and actual culture may be occurring often. Mainstream examples of cultural disparity abound with problem companies such as Enron, BP and Home Depot. In these troubled organizations, espoused values were in direct conflict with actual organiza- tional practices. Such dissonance may not lead to complete organizational failure to be worth note. Indeed, disconnects may be more subtle. For example, behavioral standards may not be practiced thoroughly by employees when manageme nt “talks-up” the importance of customer service, but does not role model the behavior. Morale may be reduced as man- agement decisions conflict with espoused organizational val- ues. The airline segment provides a good example as major carriers claim the importance of customer satisfaction, yet consistently rate lowest on factors important to customers (American Customer Satisfaction Index, 2011). Conversely, Southwest Airlines, which credits its culture to much of its success (Freiberg & Freiberg, 1997), recently scored satis- faction ratings 17 points higher than the balance of the in- dustry. In a recent survey in the hotel segment, some 78% of employees felt that their organization was committed to ser- vice quality (Savitt, 2012). At the same time, only 56% of these employees felt that their organization’s administrative policies and practices promoted the most effective service quality. There are several potential reasons for a disparity in or- ganizational culture perceptions. First, organizational culture is not a completely objective concept. In deed, components of an organization’s culture may be evaluated by different peo- ple in very different ways (Reichers & Schneider, 1990). This may be particularly true for organizational leaders who believe strongly in, and are loyal to the company. It is con- ceivable that senior managers can see their culture as positive and effective, despite evidence to the contrary. Leaders who  M. R. TESTA, L. J. SIPE demonstrate high levels of commitment to the organization and its goals may see themselves as an extension of the or- ganization (Testa, 2001). Subseque ntly , ide ntifyi ng any nega- tive factors related to the organization can be tantamount to self-criticism. Both self-theory (Snyder & Williams, 1982) and social identity theory (Ashforth & Mael, 1989) provide theoretical support for this notion. Given the need for a strong, focuse d organizational cultur e, the question becomes, what specifically needs to be streng- thened? Little has been done which helps researchers or sen- ior managers identify organizational culture gaps. More spe- cifically, little has been done which provides a purposeful assessment of the culture using an action research approach, which allows for understanding unique organizational dif- ferences. The purpose of the current study is t o illustrate how organizational culture assessment can be ambiguous, par- ticularly for senior managers. Next, a theoretical foundation for cultural analysis is provided. Finally, implementation of the culture audit process is discussed using a five-step proc- ess, with a ten-category model. This work adds to an early version of this model proposed to hospitality executives. In this expanded work, four primary differences exist. First, a review of cultural ambiguity is provided which provides greater support for the need to accurately assess the true cul- ture. Next, a full section focused on disparities in leader per- ceptions of organizati on cult ure is pr ovided to fu rther support the importance of the audit. In this more complete paper, examples of fieldwork using the model are provided as well. This helps to illustrate the varying ways the audit process may be implemented. Finally, a greate r focus on implications of the model is offered to illustrate how its use may impact organizations seeking quality guest experiences. It is hoped that this effort can be used in taking a proactive approach to improving organ izational effectivene ss as well a s a means for diagnosing the source of chronic organizational problems. Organizational Culture Ambiguity In spite of many attempts, there has been no clear consensus about the definition and measurement of organizational culture among researchers and practitioners (Deshpande & Webster, 1989). Indeed, an early study found no less than 164 varying definitions of culture (Kroeber & Kluckhohn, 1952, cited in Leidner & Kayworth, 2006). The ambiguity of culture as a construct is further illustrated by two schools of thought on how to approach culture. Some view the culture as “something the organization has” where others see it as “something the organization is” (Reichers & Schneider, 1990: p. 22; Smirchich, 1983). In the first instance, culture is used as a variable in the study of antecedents and outcomes. This allows comparison of organizations/cultures based on internal and external variables. In the second approach, the organization and the culture are indistinguishable. This “root metaphor” (Smirchich, 1983) ap- proach is more descriptive in nature and identifies the meaning connected with the culture. Using an anthropological approach, the richness of an organizational culture is identified by shared cognition, shared symbols and unconscious processes (Driskill & Brenton, 2005). The current study seeks to provide direction based on this school of thought. Definitions of culture are both numerous and varying. Some definitions simply state the central notion of culture, and others include multiple components. Table 1 provides a summary of the various definitions of culture provided in the research. Schein (1992) provides the most commonly cited definition of culture and will provide much of the foundation for the cul- ture audit discussed here. Schein defines culture as: “a pattern of shared basic assumptions learned by a group as it solved its problems of external adaptation and internal integration which has worked well enough to be considered valid and therefore, to be taught to new members as the correct way to perceive, think, and feel in relation to those problems” (p. 12). This definition identifies “assumptions” as the key compo- nent of organizational culture. An important message regarding culture is provided by Pettigrew (1990) in his summary of a collection of essays on climate and culture. The author notes that “climate and culture are complex, multidimensional, and multilevel constructs” (p. 421). As such they must be viewed at varying levels. Schein (2004) agrees providing three levels of culture which flow from the more physical to the more cogni- tive components as shown in Figure 1. At the first level are organizational artifacts. Artifacts refer to the things one might see, hear or feel when confronted with a new environment and are easily identifiable. For example, a standard guest greeting used by hotel employees or a sign high- lighting the importance of guest service may convey standards of conduct. Similarly, the physical environment, layout or cli- mate may indicate what is acceptable or not acceptable in the work environment. Schein (2004) notes that while easily ob- ser vabl e, t hese artifacts may be difficult to decipher. Put simply , symbols can be ambiguous, and subsequently may send mixed messages to the observer. For example, a new employee view- ing a manager who follows rules and policies meticulously may only describe him or her as such if past experience allows it. If the employee previously worked at an organization with ex- ceedingly strict rules and policies, he or she may interpret the new environment as lacking. Greater exposure to the culture’s deeper levels and use of a variety of artifacts to craft an accu- rate depiction becomes important to counter ambiguity. At the next level, Schein (2004) describes collective beliefs or values. Groups learn collectively and begin to create belief systems. For example, if a manager uses technology to counter a difficult scheduling problem, the group may collectively be- lieve that this is the appropriate way to confront such issues. Over time, these beliefs become ingrained in the culture and become both motivational and restrictive. Beliefs can be moti- vational in the sense that they can drive behavior, and restric- tive because they may prevent a greater range of choices or options in solving problems. An interesting conflict may emer- ge at the belief level when there is a disconnect between what the organization says it believes, and what it actually does. Stated or espoused values are not always in sync with organiza- tional action. For example, a company that says it values cus- tomers, but continues to find ways to provide lower product quality or treat employees poorly, may be out of sync. Similar to artifacts, beliefs can sometimes be so broad as to be ambiva- lent. A look at the assumptions made by the organization helps to clarify the cul ture. At the deepest level, organizations make assumptions about how the world works and how it operates within it. These as- sumptions are created over time and provide behavioral influ- ence. For example, if it is assumed that customer satisfaction is predominantly determined by the technical components of ser- vice (i.e., speed of service, efficiency, etc.), the personal side of service quality may be discounted. Further, programs and plans Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 37  M. R. TESTA, L. J. SIPE Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 38 Artifacts Observable Culture Comp o nents (10 Areas) Goals, norms and principles held by the organization Unconscious beliefs, perceptions and feelings. Source of values and action Values Assumptions Interpretation Interpretation Figure 1. Culture audit process based on Schein 2004 levels of culture model. Table 1. Definitions of organizational culture. Author Definition Rossi & O’Higgins (1980) “Culture is a system of shared cognitions or a system of knowledge and beliefs.” Hofstede (1 9 80) “The collective progra mming of the mind which distinguishes members of one human group from another.” Deal & Kennedy (1982) “The way things get done around he re.” Drennan (1992) “How things are done around here.” House, Wright & Aditya (1997) “Distinctive normative systems consisting of modal patterns o f shared psy chological properties among members of collectivities that result in compelling common affec ti ve, attitudinal, and behavioral orientations that are transm itted a cross gene rations a nd that dif fere ntiate collec tivities fr om each othe r.” Ogbonna & Lloyd (2002) “The collective sum of b eliefs, values, meanings and assumptions that are s hared by a so cial group and that help to shape the ways in which they respond to each other and to their external environment.” made to increase organizational effectiveness may be greatly influenced. To the extent those assumptions are no longer valid, it becomes easy to see that poor decisions will result. This may be commonplace in an environment with a predominant “way we do it around here” mentality. It’s important to highlight the role of interpretation in this process. One viewing a particular cultural artifact has freedom to determine the corresponding values and assumptions it re- veals. Similarly, senior managers have freedom to determine if the current organization culture is the desired organizational culture. Several obstacles may prevent leaders from accurately evaluating this symmetry. Leader Perceptions of Culture Senior managers may have the greatest impact on an organi- zations’ culture. Given their ability to control resources and decide on important organizational initiatives, senior leaders should be responsible for actions taken to craft a particular culture. This presupposes that these leaders see the need for change. Self-based theories share the common assumption that humans have a basic need to protect or improve one’s self. This essential motivation may cause highly committed managers to avoid acknowledging negative components of the organiza- tional culture. Both self-theory (ST) (Snyder & Williams, 1982; Sullivan, 1989) and social identity theory (SIT) (Ashforth & Mael, 1989) provide frameworks that might explain how senior managers might lose touch with the true organizational culture. Self-theory suggests that individuals have a basic need to maintain a positive self-image to protect psychological well- being (Snyder & Williams, 1982; Sullivan, 1989). One may develop a view of the “ideal self.” That is, a positive image which includes traits, competencies and values one would ide- ally possess (Leonard, Beauvais, & Scholl, 1999). Maintenance of this belief can become a motive for behavior. It is important to note that “self” changes reluctantly. Indeed, the more central a belief, the more likely one is to resist changing that belief. From a leadership standpoint, self-theory may contribute to an inability of some managers to see organizational negatives. For example, a senior manager who has spent considerable time and energy developing an organization is likely to be highly com- mitted to that organization and its goals, and may see his goals as a function of the organizations’. Consequently, such a man- ager may be protective of the organization just as he would be protective of himself. Seeking to develop the “ideal” image of the organization, he may consciously or unconsciously, defend any attacks on the organization. The result may be an inability to fully accept criticism or constructive feedback in the form of data, survey responses, etc. In an extreme case, rationalization may emerge with the manager seeking to maintain the positive image.  M. R. TESTA, L. J. SIPE Difficulty in spotting cultural deficiencies is further sup- ported by social identity theory (SIT) (Ashforth & Mael, 1989). Social identity theory can be viewed synonymously with group identification. The theory suggests that individuals classify themselves based on the characteristics of the groups in which they belong (Ashforth & Mael, 1989). Past research indicates that individuals who identify with a particular group (i.e., the organization) feel a strong attraction to the group as a whole (Stets & Burke, 2000). Consequently, individuals will act in concert with the group. In a practical sense, this suggests that leaders would tend to avoid acting in a way counter to the or- ganization and its needs. Although failing to see negative com- ponents of the organization may be harmful in the long-run, a consequence of SIT can be defense of the group and any nega- tivity that threatens it. Give the potential difficulty leaders may face in confronting organizational culture realities, a process which immerses the leader into the culture as means of assessment may be useful. In addition, such a process may help to counter the challenges of accurately measuring the current culture. Organizational Culture Assessment In addition to ambiguity in defining organizational culture, no clear consensus exists regarding its measurement (Desh- pande & Webster, 1989). Such measurement can be difficult as Lund (2003) points out because shared assumptions reside be- neath the conscious level. A variety of questionnaire measures exist attempting to assess culture such as the Organizational Culture Profile (Orielly et al., 1991) and the Organizational Values Congruence Scale (Enz, 1986), but tend to focus pri- marily on person-organization fit or compatibility. The issue with the person-organization fit model is its focus on individual attitudes towards the organization and does so in a quantitative way. Compatibility with the organization is not the same as a deficiency or failing effort in the organizations culture. The Competing Values Framework (Quinn, 1988) and The Organi- zational Culture Assessment Instrument (OCAI) (Cameron and Quinn, 1999) allow organizations to go farther in culture analy- sis than the previous measures. The current version of the as- sessment determines which of four typologies best describe the organization’s culture. These categories are titled Clan, Adho- cracy, Hierarchy and Market. In addition, the model will iden- tify the desired culture and allow comparison to the actual cul- ture. The limitation of the assessment is that disparities between desired and actual culture are identified in the context of the four categories and may not be as specific as necessary. Going further, the process does not allow for management involve- ment in the data collection process. Consequently, identifica- tion of deficits and actual change that needs to be addressed outside of the model may be difficult. Some criticism of questionnaire-based culture measures ex- ists, suggesting that these measures are too similar to job satis- faction measures (Hofstede, 1998; Johannesson, 1973). Sur- prisingly, little direction is provided in the way of conducting a cultural audit, which would counter the limitations of ques- tionnaire research. An early study by Wilkins (1983) provides some suggestions, but the process cannot be viewed as a mana- gerial tool. Fletcher and Jones (1992) discuss cultural auditing in terms of measurement, and attempt to provide a quantitative formula for comparison. Driskill and Brenton’s (2005) work is comprehensive and well-done, but takes an approach which may not be directly suitable in practical application. An as- sessment that provides a richer analysis of various aspects of the organizational culture may be valuable. The proposed as- sessment is designed to be broad enough to include varying types of industries, but specific enough to provide useful or- ganizational information. Given the influence of self-theory previously discussed, see- ing the culture as it truly is becomes paramount. The culture audit is an applied method of assessing the synchronicity of these cultural levels and any inconsistencies that might exist. To that end, the goals of the audit are as follows: 1) To examine cultural artifacts and determine their consis- tency with espoused values and assumptions; 2) To identify conflicts in espoused and actual beliefs and values; 3) To re-examine deeply held assumptions and identify their validity; 4) To develop an action plan for addressing inconsistencies in any of the cultu ra l l evels. The Culture Audit The ideal circumstance for conducting a culture audit is the paring of an executive team and organizational development researcher. The uniqueness of the current model is the ability to link theory and practice in a very experiential way. While the executive team can engage in much of the data collection, the researcher can guide their efforts, minimize bias and ensure the generated results are valid. A five-step model was developed for implementation of the culture audit with this executive team-researcher tandem in mind. These steps include: 1) Identification of the organization’s vision, mission, values, and strategic goals; 2) A brief narrative on the desired culture; 3) Selection of the audit team; 4) Data collection; 5) Interpretation and reporting. Step 1: Vision, Mission, Values and Strategic Goals The first step in the audit process is to clearly state where the organization is going and how it plans to get there. Clearly articulating vision, mission, values and goals will identify any inconsistencies at the strategic level. Further, statement of these important concepts will provide some direction for the type of culture necessary for their accomplishment. For example, an organization desiring to provide the highest levels of customer service, or values employees and customers, must have a cul- ture that supports these notions. In the study of organizational culture, the context in which the culture operates may be criti- cal for understanding both its strengths and weaknesses. A cur- rent overview of key organizational metrics and the “story” behind the organization may be useful as well. Step 2: Culture Narrative The focus of the culture audit is to identify disparities in the organizational culture. That is, to identify areas that are not in sync with the desired culture. Therefore, an initial step must be a clear description of the desired culture. The value of the ex- ecutive team in this process becomes evident their collective sense becomes the ultimate goal of the process. Whether or not to include other layers or departments in this process are Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 39  M. R. TESTA, L. J. SIPE dependent on the particular circumstance confronted by the researcher. A variety of questions may be asked which will help to illustrate important organizational values. For example: 1) How do you want your employees to view the organiza- tion? 2) How do you want customers to view the organization? 3) What “feeling” do you want to permeate throughout or- ganization? 4) What stories best represent what this organization stands for? 5) Who are the legendary leaders in this organization and what do they represent? The narrative should be long enough to convey important values and beliefs, but short enough that stakeholders can grasp the most important components of the culture. This description will provide the comparison necessary to identify any potential gaps in the culture. Step 3: Selection of the Audit Team To identify cultural deficits, using an executive team from varying areas of the organization would be ideal. The goal of the audit is to search for the meaning behind the artifacts, sym- bols, policies, practices, etc., that make up the organizational culture. Given the limitations of self-theory as previously dis- cussed, implementing methods to ensure objectivity becomes critical. Using leaders from accounting, operations, HR, sales and marketing, etc., may be useful by allowing for multiple view points and prevent the emergence of groupthink. Similar- ly, using a group of both new and long-tenured leaders may be valuable depending on the specific needs of the organization under review. Step 4: Data Collection A variety of methods focusing on a variety of areas should be used to collect the data for the culture audit. Taking a patch- work approach, researchers should not rely on one or two pieces of information to assess the culture, but should examine multiple aspects over multiple instances from multiples sources. This could include employee interviews, manager interviews, customer interviews and focus groups. To assess the physical artifacts of the culture, focused walk-throughs and physical plant reviews would be useful. To capture deeper components of the culture, observation of employee-employee, employee- customer, and employee-leader interactions would be revealing. Finally viewing various documents such as training manuals, orientation manuals, standard operating procedures may pro- vide insight. In the current model, ten areas of culture analysis are rec- ommended. Table 2 provides a comprehensive list of the cul- ture areas, questions to ask and specific aspects to review. Each area of analysis listed is a common element of an or- ganizational culture as described in past research (Driskill & Brenton, 2005; Kotter & Heskett, 1992; Schein, 2004). Each area of the analysis is the foundation of a gaps analysis between the stated or desired organizational culture (i.e., the narrative) and the actual organizational culture. Through a variety of ob- servations, leaders are able to compare the two, and draw con- clusions regarding the actual state of the organizational culture. Step 5: Interpretation and Reporting The final step in the audit process is to interpret the data col- lected. At face value, this may seem a direct process. However, given the potential bias that can result during such a process (see Woodman & Wayne, 1985 for a review), care must be taken in drawing conclusions regarding the results. Again, us- ing a trained researcher in this process may prevent such bias from occurring. First, results of the observation can be placed into summary worksheets. Table 3 provides an example of such a worksheet. This can be completed by the entire executive team or by sub-teams based on unique knowledge, interest, etc. The goal of the analysis is to draw down on values and assumptions that are revealed through the process. That is, the meaning behind the observations is the important factor rather than the observations themselves. To ensure objective and thorough results, several factors should be considered: 1) Combinations of observed elements to form consistent themes should be used. Rather than focusing on a single obser- vation or example, multiple examples from various sources would help to identify patterns in the culture. These patterns or themes provide the basis for identifying beliefs and assump- tions. 2) Both positive and negative observations should be utilized to form themes. Often, negative examples can be more reveal- ing then positive examples. Disconnects between desired cul- tural artifacts and observed artifacts help to create a shared sense of reality and the organizations true state. 3) Themes should be discussed in a group setting with no judgments. Members of the audit team must be able to honestly reveal their interpretation with no threat of criticism or retalia- tion. A group dialogue that allows for connections among the observers is desirable. 4) Telling stories rather than revealing facts may be valuable. Stories help to provide linkages in a thorough and compelling way. In addition, stories help to reveal deep dimensions of the culture such as values and assumptions. Stories provide a path- way for revealing the true story behind the culture. 5) Conflicts between artifacts and beliefs, as well as conflicts between espoused values and actual organizational action should be identified. These conflicts can form the basis of ac- tions that should be taken to strengthen the culture. 6) Values and assumptions should be identified by the themes that emerge. The ability to take the analysis to the root level as discussed by Schein (1992) will be a measure of the success of the audit. In addition, the validity of these assump- tions should be questioned. Are the assumptions still valid or have they been negated by innovation or changes in the mar- ketplace? 7) Findings should be used to take action. Once the results have been discussed and deciphered, the critical next step is to act based on the findings. The categories used in the culture analysis can also be used as a model for such action planning. Field Work To date, the culture audit has been used exclusively in the educational setting in both graduate and executive education. In the graduate setting, a recent group of 12 Master’s students were asked to follow the five-step model and assess their own organization. These organizations ranged from three-person small businesses to major organizations. A variety of job-situa- tions confronted the students from new hires, to those on the verge of leaving the organization. In each circumstance the student was able to successfully apply the model and identify Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 40  M. R. TESTA, L. J. SIPE Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 41 Table 2. Areas of cultural analysis. Culture Category and Questions Author What to Look For 1 Physical Characteristics an d General Environment (F-O-H vs B-O-H) What do the p hysical components of the organiza tion say about the culture? Is there consistency behind the scenes? How does it feel? Are employee and customer needs considered in the planning? Layout? Design? Hatch (199 3) Hatch & Schultz (199 7 ) Schein (1992, 2004) Signage (qua ntity and styl e) Furniture and accessories Tradition vs modern Colors Symbols & logos Lighting Sounds, level and type Uniforms Cleanliness and org anization 2 Customs & Norms What regular behaviors and expectations are in place that affect the culture? What impact do these have on the culture? Are guest needs a norm? Is facilitation of employ ee needs a norm? Farrell (2005) Hallett (2003) Schein (1992, 2004) Greetings Language & phrases Expectations set by leadership Common employee interactions Common leader-employee interactions Common leader/employee-guest interactions Unspoken rules Uniforms norms 3 Ceremonies & Events What is systematically ce l ebrated and rec o gnized at this organization? Are service champions recognized? What impact does this have on the culture? Hatch (199 3) Schein (1992, 2004) Trice & Beyer (1984) Regular staff events held Birthdays Tenure celebrations Service quality acknowledgement Certifications Holiday part i es Quarterly celebrations Formal vs. In formal gatherings 4 Rules & Policies How formalized is organization? Is the culture more rule-based or empowering? Does it strike a balance? Are rules and po l ices absolutes or guidelines? Are guest/employee needs balanced wi th p olicies? Farrell (2005) Hallett (2003) Schein (1992, 2004) What is prohibi ted vs what is permitted Number o f r u l es or polices Formal vs informal rules Depth of manuals Rule signage Number of SOPs Amount of training on policies a n d proce du r es Employee perceptions of formalization Leade r p erceptions of their role and function (rules vs empowerment vs balance) 5 Measurement & Accountability What gets measured in t h is organization? What measures are most important? Is there accountability? Are measurements consistent with vision, mission, values? Are guest and employee needs central to measurement ? Hallett (2003) Schein (1992, 2004) Types of measures used How senior leaders, supervisors and employees are evaluated Measures vs espoused Values Promotion criteria Dismissal criteria Discipline s ystem 6 Leader Behavior What do leaders make a priority here? Are leaders at varying levels role models? Do these le aders role model guest service behaviors? Which leaders are most respected here and why? How does this impact the culture? Bass & Avolio (1993) Schein (1992, 2004) Tusi et al. ( 2006) Leader focus task vs people Leader-employee interactions Leader-gue st in teractions Employee perceptions of leadership Legendary leaders Outlaw leaders 7 Rewards & Recognition What gets rewarded in this organization? How are employees recognized for their efforts? How does this impact the culture? Bushardt, Lambert, & Duhon (200 7) Milne (200 7) Schein (1992, 2004) Types and quantity of rewards provided Formal vs informal re wards Employee perception of reward value Amount of enc ouragement provided Are leaders genuine in their praise? Programs planned  M. R. TESTA, L. J. SIPE Continued 8 Training & Development What efforts are made to invest in human resources? What impact do these efforts have on the culture? Does the discipline system promote guest and employee needs? Bunch (200 7) Kissack & Callahan (2010) Amount a n d t ypes of training Certifications On-the-job vs formal Orientation processe s Service quality vs rule based efforts/technical Leadership development programs Succession planning 9 Communication How are messages, both formal and informal communicated? What is the impact on the culture? What do stories told in th is organization reveal? Are guests/employees valued or criticized in the stories told. Farrell (2005) Hallett (2003) Schein (1992, 2004) Trice & Beyer (1993) How do employees fin d things out? Email vs memos vs signage vs face-to-face Number and type of meetings Senior leader communication Are the methods effective? Are the methods appropriate? Is confidentiality ensured How much do employees find out through t he grapevine? Metaphors use d 10 Structure and Culture Development Efforts How is the organization structured? Does the organizational structure (hierarchy) impact the culture? How quickly are decisions made? Are employees empowered to solve gu est problems rapidly? Does the organization actively work towards develo p i ng its culture? Hallett (2003) Schein (1992, 2004) Smircich (1983) Layers on the organ i zational c hart Formal are the chains of command Disconnects between the top and bottom of the structure Communication barriers Vision, mission, values, goal consistency Senior leader activiti es to build the culture Employee perception of culture development efforts Employee view the culture organizational culture gaps. This required some flexibility in the approach; however the validity of the model at face value seemed apparent. Although the specific findings of each inves- tigation are beyond the scope of this paper, the ability to ac- tively engage organizational stakeholders was valuable in iden- tifying the true organizational culture and subsequent gaps. In similar fashion, the culture audit was used successfully with two groups of 30 senior leaders in the attractions industry. As part of a five-day executive education program, the execu- tives were asked to conduct an audit of a local attraction and report back to management on their findings. In this case, the cultural narrative came after the audit to be used as a compari- son to the findings. This removed any bias that might emerge after the desired culture was identified. Working in three-per- son teams, the executives spent a full-day at the attraction en- gaging staff, observing interactions, assessing front and back areas, and speaking with departmental leaders. Again, at face value, the audit appears to provide a means for identifying some cultural gaps. While further study is required, these pre- liminary findings are encouraging. Implications The intangible, co-constructed nature of the customer experi- ence makes measuring business performance difficult, particu- larly where stakeholder and customer interactions take place (Gallouj, 2002). The culture audit provides an opportunity to assess business performance beyond guest satisfaction ratings or financial me trics. T he model prese nte d here allows ma nagers to examine how the product is delivered in their organization as well as what the customer observes. Essentially, it provides an opportunity to blend assessment of what the guest experiences with what the employee experiences. Given the linkage and interdependence of the two groups, this may be very valuable. In addition, the cultural audit process provides an opport uni t y f or managers to practice making rounds of their organizations with the sole purpose of enhancing organizational culture. The structure of the audit provides a focus that goes beyond just “management by walking around” or empty face time. It is similar to the notion of “rounding for outcomes” introduced by the health care industry. Much like physicians make patient rounds, the leading healthcare organizations encourage the rounding for outcomes process as a way to encourage managers to focus on the positive with their employees (Studer, 2003). Having a plan when making rounds has become common prac- tice for senior leaders in healthcare and is cited by some as critical to improvements in both patient and employee satisfac- tion scores (Hotko, 2004). The cultural audit offers a structured approach to purposeful rounding for organizational leaders. Finally, the result of the audit process should be a greater understanding of the true organizational culture. Leaders seek- ing to deliver the highest levels of service or maximizing guest experiences have a critical need for such an understanding. Simply put, leaders can make better decisions regarding their organization, operations, and various stakeholders when more complete information is available. An audit as described here can help in this regard. Going farther, regardless of the out- comes, the audit process itself may be seen positively by em- ployees. By actively engaging employees to identify their per- ceptions, challenges, successes and failures, the culture itself is positively impacted. Indeed, the dialogue that emerges moves the organization closer to i ts vision. Conclusion The purpose of this study was to illustrate how organiza- tional culture can be an ambiguous construct and show why leaders may have difficulty identifying their true culture. In addition, this study provides a teoretical foundation for, and h Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 42  M. R. TESTA, L. J. SIPE Table 3. Audit summary sheet e xa mple. Culture Category What to Look For Gaps 1 Physical Characteristics an d General Envir onment (F-O-H vs B-O-H) What do the ph ysical components o f the organization say about the culture? Is there consistency behind the scenes? How does it feel? Are employee and customer needs considered in the planning? Layout? Design? Signage (qua ntity and styl e) Furniture and accessories Tradition vs Modern Colors Symbols & logos Lighting Sounds, level and type Uniforms Cleanliness and org anization Actions to Be Taken: 2 Customs & Norms What regular behaviors and expectations are in place that affect the culture? What impact do these have on the culture? Are guest needs a norm? Is facilitation of employ ee needs a norm? Greetings Language & phrases Expectations se by leadership Common employee interactions Common leader-employee interactions Common leader/employee-guest interactions Unspoken rules Uniforms norms Actions to Be Taken: practical means to, conducting an organizational culture audit to counter these issues. It seems clear that a compelling culture would be beneficial in gaining competitive advantage. In an effort to craft such a culture, an action research model is pro- posed which should allow leaders and their executive commit- tees to conduct a thorough assessment of their culture. By iden- tifying deficiencies or gaps, action may be taken to strengthen the culture. In addition, this process may be valuable in that it stimulates dialogue among the executive team. Using an action research approach, this process facilitates discussion among the key decision makers regarding both the desired and actual cul- ture. It is hoped the direction provided here is useful for re- searchers seeking a deeper assessment of culture, particularly in the field setting, however several limitations exist. First, cultural auditing can be a very complex task and one that requires careful application. This model may simplify the process, but caution must be used in both the data collection and the interpretation. Next, while many areas of organizational culture are provided here, the model may not be useful for all organizations as is. Every culture is different and there may be additional areas of analysis that should be included. This study should however provide an adequate starting point for varying types of organizations. Next, further study of, and application of the model is required. While some face validity is provided from the field work described here, more rigorous testing is needed. Finally, the literature on organizational culture is vast. While mainstay authors and studies have been included, an expanded version of this model can pay greater attention to components of culture assessment that could not be addressed here. REFERENCES American Customer Satisfaction Index (2011). ACSI commentary June 2011. http://www.theacsi.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=articl e&id=256:acsi-commentary-june-2011&catid=14&Itemid=335 Ashforth, B. E., & Mael, F. (1989). Social identity theory and the or- ganization. Academy of Management Review, 14, 20-39. Bass, B. M., & Avolio, B. J. (1993). Transformational leadership and organizational culture. Public Administration Quarterly, 17, 112- 121. Birnbaum, D., & Sommers, M. J. (1986). The influence of occupational image subcultures on job attitudes, job performance, and the job atti- tude-job performance relationship. Human Relations, 39, 661-672. doi:10.1177/001872678603900705 Bunch, K. (2007). Training failure as a consequence of organizational culture. Human Resource Developm e n t R e v i e w , 6, 142-163. doi:10.1177/1534484307299273 Bushardt, S. C., Lambert, J., & Duhon, D. L. (2007). Selecting a better carrot: Organizational learning formal rewards and culture—A be- havioral perspective. Journal of Organizational Culture, Communi- cation and Conflict, 11, 67-79. Cameron, K. S., & Quinn, R. E. (1999). Diagnosing and changing or- ganizational cultur e. New York, NY: Addison Wesley. Denison, D. R., & Mishra, A. K. (1995). Toward a theory of organiza- tional culture and effectiveness. Organizational Science, 6, 204-223. doi:10.1287/orsc.6.2.204 Deshpande, R. & Webster, F. E. (1989). Organizational culture and marketing: Defining the research agenda. Journal of Marketing, 53, 3-15. doi:10.2307/1251521 Drennan, D. (1992). Transforming company culture. London: McGraw- Hill. Driskill, G.W., & Brenton, A. L. (2005). Organizational culture in ac- tion: A cultural analysis workbook. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publica- tions. Enz, C. A. (1986). Power and shared values in the corporate culture. Ann Arbor: UMI Research Press. Farrell, M. A. (2005). The effect of market-oriented organisational cul- ture on sales-force behavior and attitudes. Journal of Strategic Mar- keting, 13, 261-273. doi:10.1080/09652540500338295 Fletcher, B., & Jones, F. (1992). Measuring organizational culture: The cultural audit. Managerial A cc o un ti ng Journal, 7, 30-36. doi:10.1108/eb017606 Freiberg, K. & Freiberg, J. (1997). Nuts! Southwest Airlines’ crazy recipe for business and personal success. New York, NY: Broadway Books. Gallouj, F. (2002). Innovation in services and the attendant old and new myths. Journal of Socio-Economics, 31, 137-154. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 43  M. R. TESTA, L. J. SIPE doi:10.1016/S1053-5357(01)00126-3 Hallett, T. (2003). Symbolic power and organizational culture. Socio- logical Theory, 21, 128-149. doi:10.1111/1467-9558.00181 Hatch, M. J. (1993). The dymanics of organizational culture. The Acad- emy of Management Review, 18, 657-693. Hatch, M. J., & Schultz, M. (1997). Relations between organizational culture, identity and image. European Journal of Marketing, 31, 356- 365. doi:10.1108/eb060636 Hofstede, G. (1980). Motivation, leadership, and organization: Do Am- erican theories apply abroad? Organizational Dynamics, 9, 42-58. doi:10.1016/0090-2616(80)90013-3 Hofstede, G. (1988). Attitudes, values and organizational culture: Dis- entangling the concepts. Organization Studies, 19, 477-492. doi:10.1177/017084069801900305 Hotko, B. (2004). Rounding for outcomes. Studer Group Newsletter, 1, 1. House, R. J., Wright, N., & Aditya, R. N. (1997). Cross-cultural re- search on organizational leadership: A critical analysis and a pro- posed theory. In P. C. Earle y, & M. E rez (Eds .), New perspectives on international/organizational psychology (pp. 535-625). San Fran- cisco: New Lexington. Kemp, S., & Dwyer, L. (2001). An examination of organizational cul- ture—The Regent Hotel, Sydney. International Journal of Hospital- ity Management, 20, 77-93. doi:10.1016/S0278-4319(00)00045-1 Kissack, H. C., & Callahan, J. L. (2010). The reciprocal influence of organizational culture and training and development programs. Jour- nal of European Industrial Training, 34, 365-380. doi:10.1108/03090591011039090 Kotter, J. P., & Heskett, J. L., (1992). Corporate culture and perform- ance. New York: Free Press. Leonard, N. H., Beauvais, L. L., & Scholl, R. W. (1999). Work motive- tion: The incorporation of self-concept-based processes. Human Re- lations, 52, 969-998. doi:10.1177/001872679905200801 LeBlanc, C. L., & Mills, K. E. (1995). Competitive advantage begins with positive culture . Nation’s Restaurant News, 29, 22-24. Leidner, D. E., & Kayworth, T. (2006). Review: A review of culture in information systems research: Toward a theory of information tech- nology culture conflic t . MIS Quarterly, 30, 357-399. Lund, D. (2003). Organizational culture and job satisfaction. Journal of Business & Industrial M a r k et i n g , 18, 219-236. doi:10.1108/0885862031047313 Milne, P. (2007). Motivation, incentives and organisational culture. Journal of Knowledge Management, 1 1, 28-38. doi:10.1108/13673270710832145 Ogbonna, E., & Lloyd, C. H. (2002). Managing organizational culture: Insights from the hospitality industry. Human Resource Management Journal, 12, 33-53. doi:10.1111/j.1748-8583.2002.tb00056.x O’Reilly, C. A., Chatman, J. A., & Caldwell, D. F. (1991). People and organizational culture: A profile comparison approach to assessing person–organization fit. Academy of Management Journal, 34, 487- 516. doi:10.2307/256404 Quinn, R. E. (1988). Beyond rational management. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Reichers, A. E., & Schneider, B. (1990). Climate and culture: An evo- lution of constructs. In B. Schneider (Ed.), Organizational climate and culture (pp. 5-39). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Reichfield, F., & Sasser, W. (1990). Zero defections: Quality comes to customer service. Harvard Business Review, 68, 105-111. Savit, M. (2012). Above and beyond. Lodging Magazine, 37, 42-44. Schein, E. (1992). Organizational culture and leadership (2nd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Schein, E. (2004). Organizational culture and leadership (3rd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Smircich, L. (1983). Concepts of culture and organizational analysis. Administrative Science Quarterly, 28 , 339-358. doi:10.2307/2392246 Snyder, R. A., & Williams, R. R. (1982). Self-theory: An integrative theory of work motivation. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 55, 257-267. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8325.1982.tb00099.x Stets, J. E., & Burke, P. J. (2000). Identity theory and social identity theory. Social Psychology Quarterly, 63, 224-237. doi:10.2307/2695870 Studer, Q. (2003). Hardwiring excellence: Purpose, worthwhile work, making a difference. Gulf Breeze, FL: Fire Starter Publishi ng . Sullivan, J. J. (1989). Self theories and employee motivation. Journal of Management, 15, 345-363. Testa, M. R. (2001). Hospitality leaders: Do they know how their em- ployees feel about them? Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administra- tion Quarterly, 42, 80-89. Tidball, K. H. (1988). Creating a culture that builds your bottom line. Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Quarterly, 29, 63- 69. doi:10.1177/001088048802900118 Trefry, M. G. (2006). A double-edged sword: Organizational culture in multicultural organizations. International Journal of Management, 23, 563-575. Trice, H. M., & Beyer, J. M. (1984). Studying organizational culture through rites and ceremonials. Academy of Management Review, 9, 653-669. Trice, H. M., & Beyer, J. M. (1993). The cultures of work organizations. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. Tsui, A. S., Zhang, Z. X., Wang, H., Xin, K. R., & Wu, J. B. (2006). Unpacking the relationship between CEO leadership behavior and organizational culture. The Leadership Quarterly, 17, 113-137. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2005.12.001 Ueno, A. (2010). What are the fundamental features supporting service quality? Journal of Services Marketing, 24, 74-86. Woodman, R. W., & Wayne, S. J. (1985). An investigation of posi- tive-findings bias in evaluation of organization development inter- ventions. Academy of M an a g em e nt J ou r n al , 28, 889-913. doi:10.2307/256243 Wilkins, A. L. (1983). The culture audit: A tool for understanding or- ganizations. Organizational D yn a m i cs, 12, 24- 39. doi:10.1016/0090-2616(83)90031-1 Xenikou, A., & Simosi, M. (2006). Organizational culture and trans- formational leadership as predictors of business unit performance. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 21, 566-579. doi:10.1016/0090-2616(83)90031-1 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 44

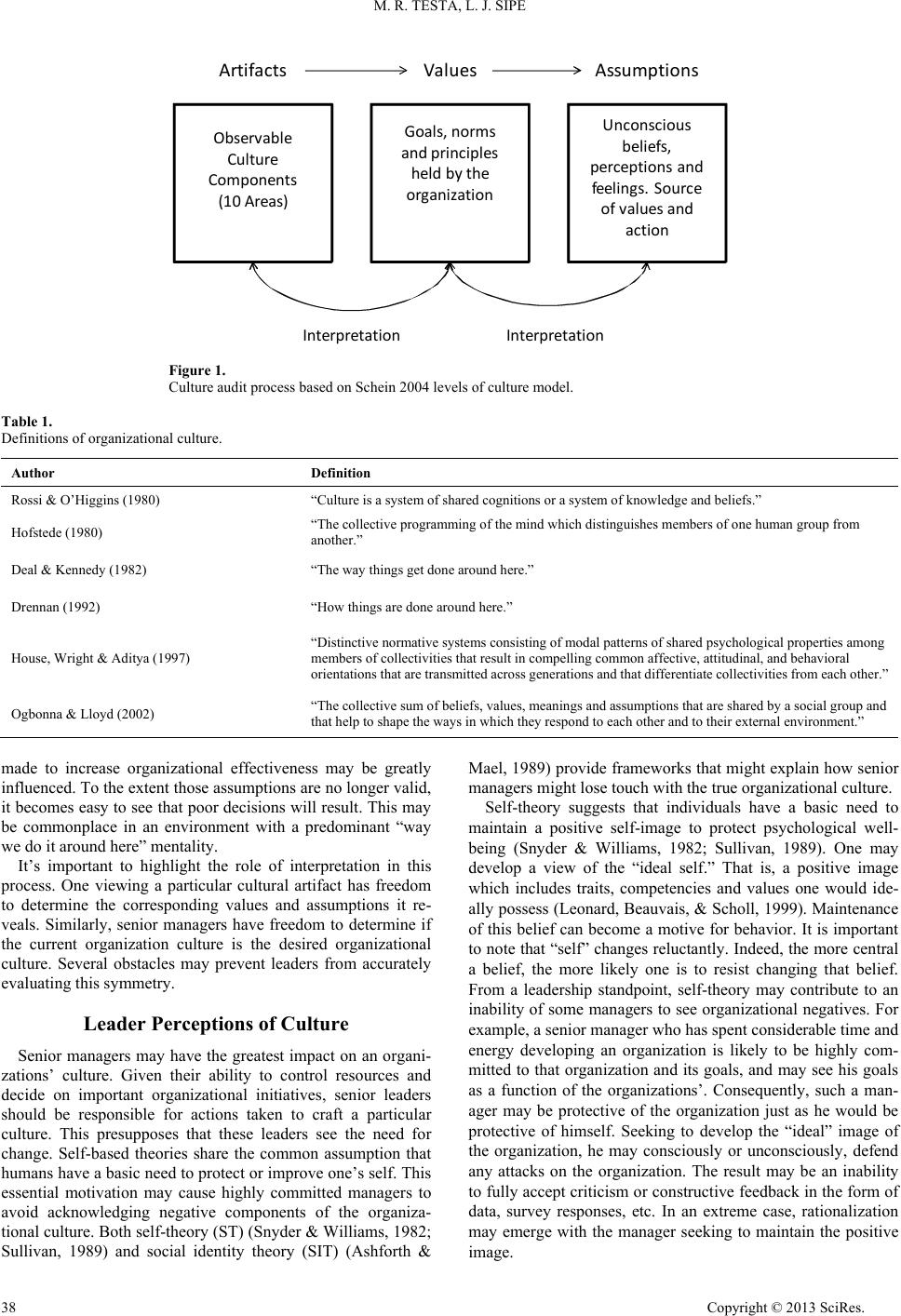

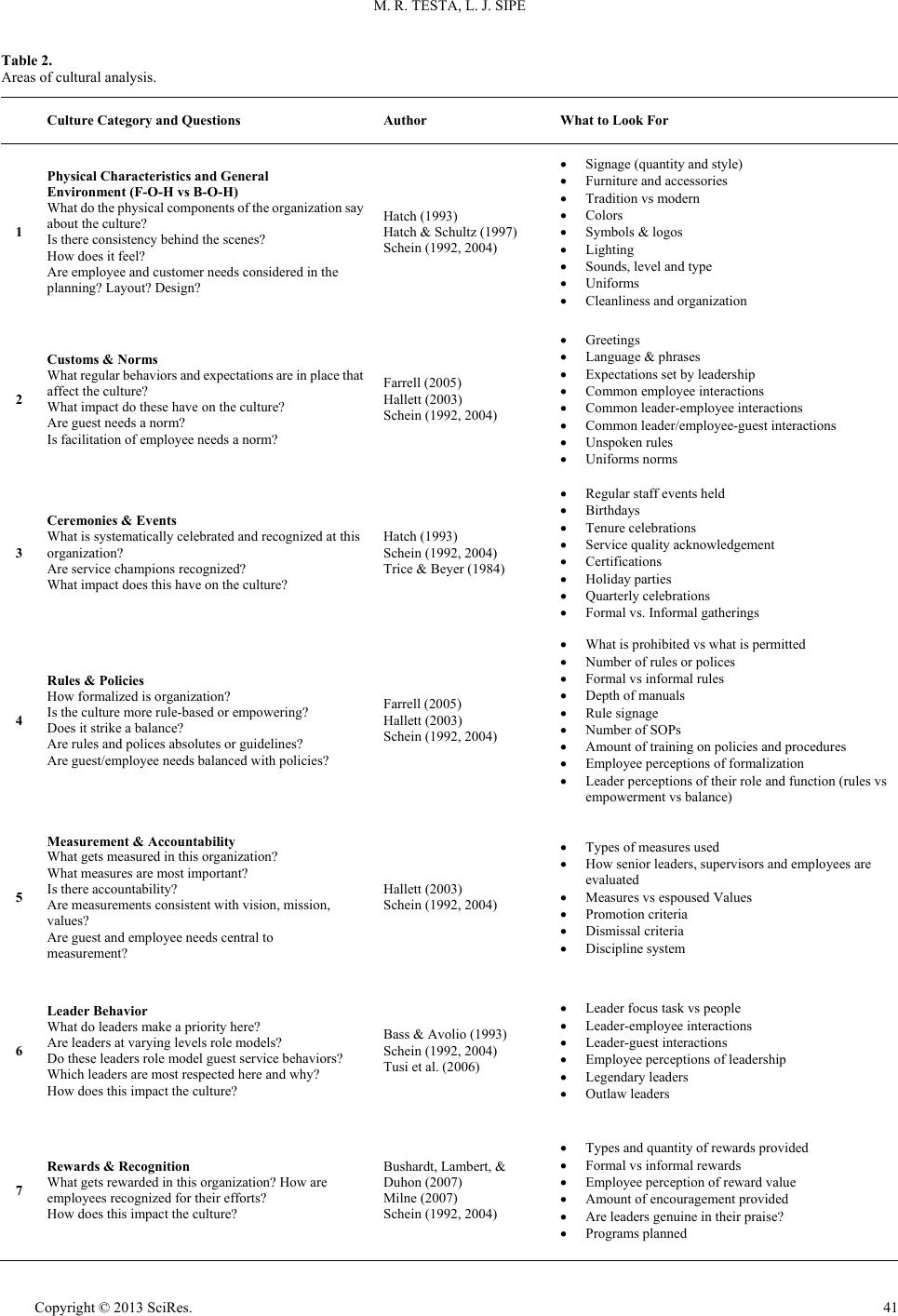

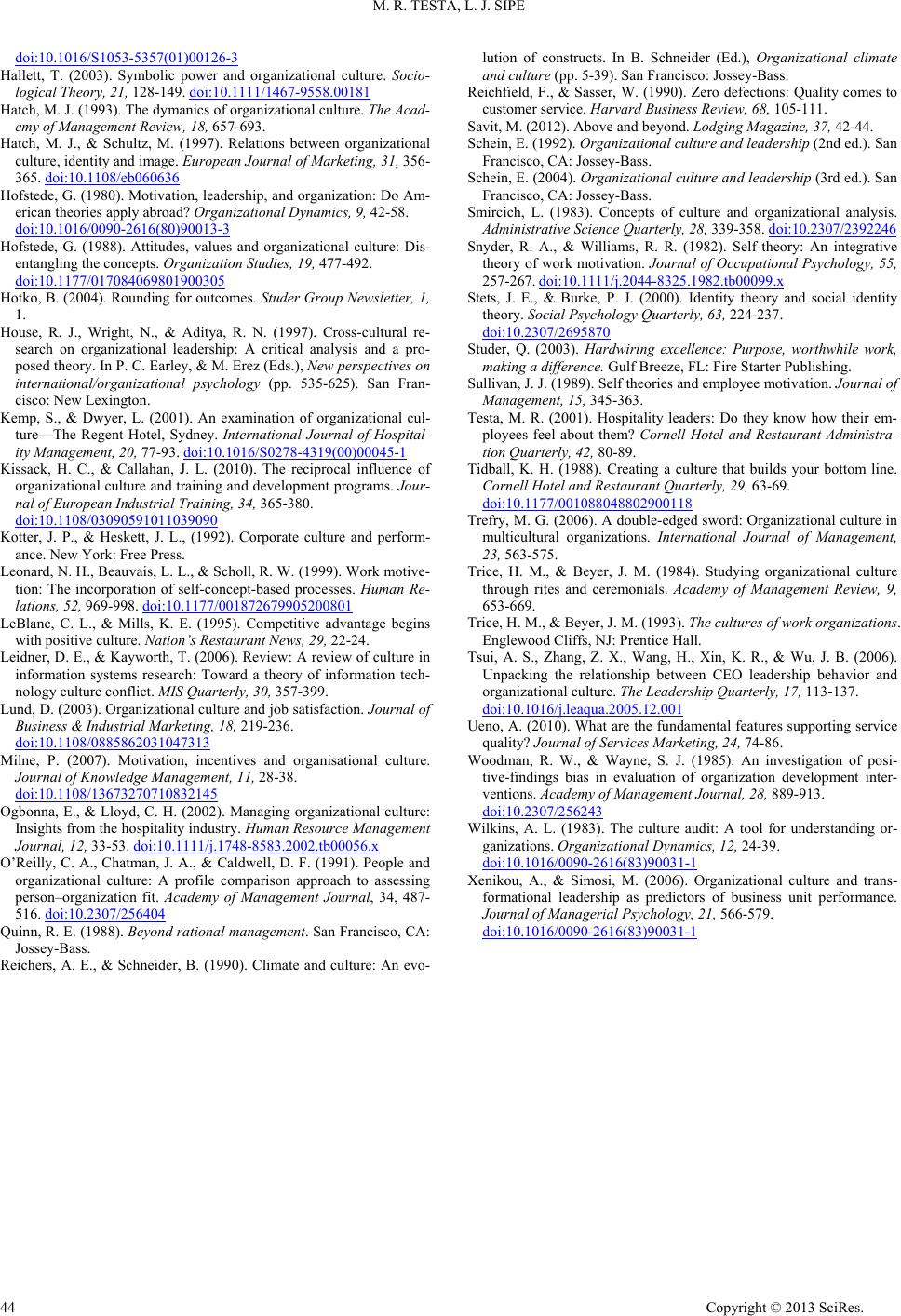

|