Open Journal of Respiratory Diseases, 2013, 3, 97-106 http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojrd.2013.32015 Published Online May 2013 (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ojrd) Sleep Quality among Hispanics of Mexican Descent and Non-Hispanic Whites: Results from the Sleep Health and Knowledge in US Hispanics Study Xavier Soler1*, Carolina Diaz-Piedra2, Wayne A. Bardwell1, Sonia Ancoli-Israel1, Lawrence A. Palinkas1,3, Joel E. Dimsdale1, Jose S. Loredo1 1University of California San Diego, San Diego, USA 2University of Granada, Granada, Spain 3University of Southern California, Los Angeles, USA Email: *xsoler@ucsd.edu Received April 1, 2013; revised May 3, 2013; accepted May 10, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Xavier Soler et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. ABSTRACT Objectives: To investigate differences in sleep quality between Hispanics of Mexican descent (HMD) and Non-His- panic Whites (NHW) and evaluate the effect of acculturation to the US lifestyle in sleep health. We hypothesize that the detrimental effect of acculturation on health outcomes will impact sleep quality among HMD. Design: We performed a population-based random digit dialing telephone survey to determine sleep quality in HMD and NHW. We collected from 3667 subjects, demographics, previous diagnosis of depression or anxiety, past treatment for sleep disorders, the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) and the Short Acculturation Scale for Hispanics. Results: The prevalence of poor sleep quality (PSQI > 5) was 64.4% for HMD and 64.3% for NHW (p = 0.93). A prior diagnosis of depression or anxiety was an independent predictor of poor sleep quality in both groups (OR 3.4 and 2.7 for HMD and NHW. Ethnic- ity was not a predictor of poor sleep quality in HMD or NHW. Acculturation was not a predictor of poor sleep quality in HMD. However, highly acculturated young HMD males had significantly more prevalence of poor sleep quality com- pared to NHW (64.8% vs. 49.8%, p < 0.001). Conclusion: The absence of sleep quality differences in a large sample of HMD and NHW living in San Diego County is contrary to current data of having poorer sleep quality among Latinos. We found that neither ethnicity nor acculturation were predictors of poor sleep quality in HMD. However, we demon- strated a highly prevalent poor sleep quality among the two ethnic groups. The finding of significantly lower sleep qual- ity in young highly acculturated HMD men may represent the heterogeneity of ethnicity related to sleep. Programs to improve sleep quality in subjects with depression and/or anxiety, and in young highly-acculturated HMD seems war- ranted. Keywords: Sleep Quality; Race/Ethnicity; Acculturation; Hispanics; Latinos; Mexican-Americans; PSQI 1. Introduction Sleep is restorative in daily functioning [1] and is intrin- sically important in sustaining physical and psychosocial well-being that theoretically is thought to be dependent of ethnicity and culture [2,3]. Furthermore, sleep disor- ders are linked to poor mental and physical health and directly impact quality of life [4-8]. Prior studies have suggested ethnic differences in sleep-related disorders such as obstructive sleep apnea, restless legs syndrome, insomnia, and in sleep continuity and architecture [9-19]. The majority of sleep research has been conducted in Non-Hispanic Whites (NHW), and to a lesser extent in African-Americans and Asians. Therefore, these results cannot be easily generalized to other ethnic groups such as Hispanics, the second largest ethnic group and the fastest-growing minority in the United States [20,21]. An understanding of the epidemiology of sleep disorders among different ethnic groups is of key importance to appreciate the links between sleep problems and cardio- vascular disorders such systemic hypertension, stroke or metabolic syndrome, quality of life, and the use of medi- cal care among general populations [22]. As part of the Sleep Health and Knowledge in US Hispanics project (aimed at characterizing sleep disorders and health-re- *Corresponding author. C opyright © 2013 SciRes. OJRD  X. SOLER ET AL. 98 lated knowledge of Hispanics of Mexican descent (HMD) and NHW in San Diego County), we studied ethnic dif- ferences on sleep quality on both groups. Because ethnic differences in health outcomes may be attributable to both biological and environmental factors, we also wished to determine the role of acculturation in sleep quality in this population, questions that are relevant for future public health policies planning on these groups. Assum- ing that acculturation may negatively impact health out- comes, [23] we hypothesize that HMD will have signifi- cantly poorer sleep quality compared to the group of NHW measured with the PSQI. 2. Methods 2.1. Subjects From January 2007 to September 2009, a total of 149,552 phone numbers were randomly dialed from which 14,162 households responded and showed interest in participat- ing in the telephone survey (9.5% of response rate). Of these, 10,495 (74%) were not qualified to participate be- cause no one in the household was HMD or NHW or over quota for NHW in 59 cases. To be included in the study, subjects should have >18 years old, self-identified as HMD or NHW ethnic group, and living in San Diego County, California. A total of 3667 subjects were ana- lyzed (1754 HMD and 1913 NHW). Informed consent was obtained over the telephone. Only subjects with complete and valid responses to the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) were included in the analyses. Cases were excluded when discrepancies were found in the reports. For instance, if the subject reported habitual sleep duration longer than the habitual sleep period (i.e. patient reporting to sleep usually 9 hours, and in follow- ing question answered going to bed at 11 pm and waking up at 6 am, so time in bed is 7 hours total). Also, subjects reporting sleeping time greater than 12 hours were ex- cluded. Final analyzed sample was 3138 subjects. The study was approved by the University of California San Diego Human Research Protections Program. 2.2. Study Design The Waksberg random digit dialing procedure was used for recruitment [24]. This method is used for popula- tion-based epidemiological studies. A computerized da- tabase randomly assign and call phone numbers based in a previously criteria of interest. It permits to accurately select populations having certain characteristics such gender or ethnicity. The survey was administered by trained, bilingual, culturally competent telephone inter- viewers (California Survey Research Services, Inc., Van Nuys, CA) utilizing a computer assisted telephone inter- view system. In order to adjust for the racial/ethnic dis- tribution of the San Diego County population, zip codes with higher concentrations of Mexican Americans were over sampled. Once a qualifying household was identi- fied a randomization procedure was utilized to recruit only one adult participant per household. The survey took approximately 40 minutes to com- plete. We included: 1) demographics; 2) the sleep quality questionnaire (PSQI) (25); 3) prevalence of smoking, alcohol use, coffee use; 4) a previous diagnosis of anxi- ety and/or depression (“have you ever been told that you have had anxiety and/or depression?”); 5) and existence of sleep disorder treatments (“have you ever been treated for a sleep disorder?”). HMD subjects were also asked to take the Short Acculturation Scale for Hispanics [25]. The telephone questionnaires were administered in Eng- lish or Spanish based on participant’s preference. 2.3. Evaluation of Sleep The PSQI assesses subjective sleep quality and sleep disturbances over the previous month. It consists of 19 items evaluated over 7 domains that include subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleep medication- sand daytime dysfunction. Domains are scored on a 0 to 3 scale where 3 indicate severe impairment. The 7 sub- scale scores are then totaled to provide a global PSQI score, which has a range of 0 - 21, with higher scores indicating worse sleep quality [26]. The PSQI has estab- lished acceptable reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.82 - 0.89) and validity (specificity rates to the clinical diag- nosis of insomnia: 80% - 100%). Global scores > 5 were interpreted as an indicator of poor sleep quality. Both English and Spanish versions of the PSQI were available for administration. The PSQI has been translated into Spanish by various authors and validated in Spanish speaking populations in Spain, [27] Colombia, [28] and Mexico [29]. Each translation varies slightly. We made minor changes to some of the expressions to adapt the instrument to a telephone interview format and to the Mexican American population. For example, question 5c, we used “baño” instead of “servicio” to denote the bath- room. 2.4. Evaluation of Acculturation Level Those subjects identifying themselves as HMD were further asked to take the Short Acculturation Scale for Hispanics, a 12-item validated instrument, available in both English and Spanish, which provides a global nu- merical measure of acculturation to the American life- style based on language familiarity and usage, language preference in media interactions, ethnic social and per- sonal interaction and identity. HMD participants were classified as highly acculturated or leastacculturated based Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OJRD  X. SOLER ET AL. 99 Table 1. Hispanics of Mexican descent and non-Hispanic Whites characteristics. on whether their acculturation score fell above or below the group median. Higher scores suggest more accultura- tion. HMDa NHWb n 1445 1693 p Gender (% Male/Female) 42.5/57.5 50.6/49.4<0.001 Age (years, mean ± SD) 41.5 ± 15.8 55.4 ± 17.2<0.001 BMIc (kg/m2, mean ± SD) 28.1 ± 6.5 27.2 ± 5.7<0.001 Smokers (%) 15.2 19.1 0.005 Alcohol consumers (%) 33.1 51.2 <0.001 Caffeine consumers (%) 64.3 65.5 0.469 Sleep disorders treatment (%) 8.7 14.9 <0.001 Depression/anxiety diagnosis (%)27.6 31.4 0.061 2.5. Statistical Analysis Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 17.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Descriptive statistics for continuous variables were expressed as means with standard deviations, and categorical data were described as frequencies and percentages. “Don’t know” and “Re- fuse to answer” responses were set to missing values and excluded from analyses. Student t-tests were used to compare mean values of PSQI. Pearson’s Chi-Square test was used to compare frequency data. For each ethnic group, anxiety, depression, gender, age and use of to- bacco, alcohol and/or coffee scores were entered in to logistic regression models taking PSQI score value (≤5 vs. >5) as the dependent variable. Acculturation was in- cluded in the Hispanic model. Post hoc analyses of prevalence of poor sleep quality were performed on HMD data dividing the population by the median age into young and older adults (≤47 and ≥48 years, respec- tively). A p value < 0.05 was regarded as statistically sig- nificant. aHispanics of Mexican descent; bNon-Hispanic Whites; cBody mass index. Table 2. Least and highly acculturated Hispanics of Mexi- can descent characteristics. Least acculturated HMDa Highly acculturated HMDa n 898 541 p Gender (% Male/Female) 39.5/60.5 47.3/52.7 Age (years, mean ± SD) 42.6 ± 15.8 39.6 ± 15.6<0.001 BMIb (kg/m2, mean ± SD) 28.1 ± 6.8 28.1 ± 6.00.977 Smokers (%) 13.8 17.4 0.068 Alcohol consumers (%) 25.7 45.3 <0.001 Caffeine consumers (%) 69.3 56 <0.001 Sleep disorder treatment (%) 8.8 8.5 0.920 Depression/ anxiety diagnosis (%)27.8 27 0.692 Poor sleep quality (PSQIc > 5) 62.6 67.2 0.077 3. Results 3.1. Socio-Demographic Variables Subject characteristics appear in Table 1. From the 3138 subjects that were analyzed (1445 HMD and 1693 NHW), 1471 were males and 1667, females. HMD were signifi- cantly younger than NHW (41.5 ± 15.8 years old vs. 55.4 ± 17.2 years old, p < 0.001). Table 2 shows the subject characteristics of highly acculturated vs. least accultur- ated HMD. In general, highly acculturated Hispanics were younger, had a higher prevalence of use of alcohol and lower prevalence of use of caffeinated beverages. There was no difference in BMI, prevalence of smoking, prior treatment for sleep disorders or previous diagnosis of anxiety and/or depression between highly and least acculturated Hispanics. aHMD = Hispanics of Mexican descent; bBMI = Body mass index; cPitts- burgh Sleep Quality Index. acculturated, compared with the least acculturated was not significantly different (67.2% vs. 62.6%, p = 0.077), Table 2. Assessment of PSQI individual components (subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbance, use of sleep- ing medication and daytime dysfunction) showed sig- nificant differences between both ethnic groups only in the use of sleeping medication and habitual sleep effi- ciency. HMD were less likely to use sleep medication than NHW (17.2% vs. 28.8%, p < 0.001), and reported significantly lower sleep efficiency (83.8% ± 14.7 vs. 85.6% ± 13.6, p = 0.001). 3.2. Subjective Sleep Quality Table 3 depicts reported sleep quality as measured by the PSQI in both HMD and NHW. The proportion of sub- jects reporting poor sleep quality was not significantly different between HMD and NHW (64.4% and 64.3% for HMD and NHW respectively, p = 0.933). There was also no significant difference in the mean PSQI global score between ethnic groups (6.65 ± 4.1 for HMD vs. 6.67 ± 4.1 for NHW, p = 0.904). On average, women reported significantly worse sleep quality than men (PSQI global scores 7.0 ± 4.2 vs. 6.2 ± 3.8, p < 0.001). The proportion of HMD reporting poor sleep quality among the highly 3.3. Predictors of Sleep Quality We performed logistic regression analysis to determine risk factors for poor sleep quality in the overall sample and for HMD and NHW separately. When the entire population was included, ethnicity was not a risk factor Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OJRD  X. SOLER ET AL. 100 Table 3. Pittsburgh sleep quality index sub-scale scores for Hispanics of Mexican descent and Non-Hispanic Whites (Mean ± SD). HMDa NHWb n 1445 1693 p PSQIc Components PSQI 1: Subjective sleep quality 1.03 ± 0.82 0.99 ± 0.810.176 PSQI 2: Sleep latency 1.14 ± 0.95 1.09 ± 0.970.102 PSQI 3: Sleep duration 1.02 ± 1.08 1.13 ± 1.190.075 PSQI 4: Sleep efficiency 0.74 ± 0.99 0.63 ± 0.970.001 PSQI 5: Sleep disturbances 1.25 ± 0.68 1.26 ± 0.600.613 PSQI 6: Sleep medication use 0.39 ± 0.92 0.67 ± 1.14<0.001 PSQI 7: Daytime dysfunction 0.89 ± 0.92 0.89 ± 0.810.934 Sleep efficiency (%) 83.80 ± 14.68 85.56 ± 13.630.003 Poor sleep quality (PSQI > 5, %) 64.4 64.3 0.933 Poor sleep quality (PSQI > 5, %) (M/Fd) 59.9 / 67.7 61.6 / 66.90.012/ 0.002 PSQI global index 6.65 ± 4.10 6.67 ± 4.060.904 aHispanics of Mexican descent; bNon-Hispanic Whites; cPittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; dMale/Female. for sleep quality after controlling for age, gender, BMI, smoking, use of alcoholic or caffeinated beverages, re- ported presence of sleep disorders or reported diagnosis of anxiety or depression. Ta ble 4 shows the predictors of poor sleep quality for HMD. In HMD, a reported diagno- sis of depression or anxiety (OR 3.444, 95% CI 2.512, 4.722, p < 0.001) and being female (OR 1.388, 95% CI 1.091, 1.766, p = 0.008) were independent predictors of poor sleep quality. Acculturation to the US lifestyle was not a predictor of poor sleep quality. Highly acculturated young HMD males had a significantly higher prevalence of poor sleep quality (64.8% vs. 49.8% p < 0.001) after Bonferroni correction, than older HMD males, or women regardless of acculturation status (Figure 1). Table 5 shows the predictors of poor sleep quality for NHW. In NHW, the report of a diagnosis of depression or anxiety was the strongest independent risk factor for poor sleep quality (OR 2.699, 95% CI 2.093, 3.481, p < 0.001). In addition, being female (OR 1.26, 95% CI 1.015, 1.564, p = 0.036) and smoking (OR 1.656, 95% CI 1.240, 2.212, p = 0.001) were independent predictors and age and BMI were weak but statistically significant predictors of poor sleep quality. 4. Discussion The present study examined subjective sleep quality in a large sample of US HMD living in San Diego County (California, US) and compared them to NHW. We dem- onstrated that that poor sleep quality is highly prevalent in 49.8 69 63.4 72.0 64.8 65.0 70.3 68.2 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 Least Acculturated Highly Acculturated p<0.05 a Short Acculturation Scale for Hispanics Figure 1. Sleep quality and acculturation by age and gender in Hispanics of Mexican-descent. The results show no dif- ferences among less and highly acculturated women. How- ever, young highly acculturated men had significantly poorest sleep quality compared with least acculturated young men adults (p < 0.001). HMD and NHW living in San Diego County, CA, but not significantly different between these ethnic groups. We found that the strongest predictor of poor sleep qual- ity was the prior diagnosis of depression or anxiety. In addition, our data suggest that the level of acculturation to the US lifestyle could play a significant role in deter- mining an impaired sleep quality among young HMD men. Previous research in general population has shown a great variability in the prevalence of poor sleep quality, [30-32] however; it is not clear yet what causes these heterogenic results. For example, Buysse et al. found poor sleep quality on the PSQI in 50.8% of 187 adults in a US community sample where 41.2% were African- Americans, [31,32] while Ramsawh and collaborators found poor sleep quality in 35% of 4181 German sub- jects using the PSQI as well [31,32]. In our large sample, we found an even higher prevalence of poor sleep quality among subjects. For instance, sleep complaints and prevalence of poor sleep quality may be affected by the measuring instrument, race/ethnic, age, and gender pro- portions, health status, socioeconomic and cultural makeup of the study population, all of which may ex- plain the differences among studies published comparing ethnic groups [30,32,33]. In the recent Sleep America Poll 2010, which focused on ethnicity, the reported prevalence of sleeping poorly at least one day a week was 60% regardless of ethnicity, results comparable to our findings [34]. It is important to notice, that there have been very few researches exploring thoroughly sleep dis- turbances among different ethnic groups and furthermore, studies among Hispanics are almost nonexistent. With few exceptions, US Hispanics are only a small proportion of epidemiologic studies, although it is the second largest ethnic group in the United States [16]. In a study evalu- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OJRD  X. SOLER ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OJRD 101 Table 4. Risk factors of poor slee p quality (Pittsburgh sleep quality index global index > 5) for Hispanics of Mexican descent (n = 1386). 95% CI for Exp(B) Variables in the equation B SE Wald df Sig. Exp(B) Lower Upper Depression/ anxiety 1.237 0.161 58.994 1 <0.001 3.444 2.512 4.722 Sleep disorder 0.388 0.269 2.084 1 0.149 1.474 0.870 2.496 Gender 0.328 0.123 7.130 1 0.008 1.388 1.091 1.766 Alcohol 0.255 0.132 3.739 1 0.053 1.290 0.997 1.670 Smoking 0.214 0.169 1.599 1 0.206 1.239 0.889 1.726 Acculturation 0.184 0.124 2.205 1 0.138 1.202 0.943 1.534 BMI 0.004 0.010 0.211 1 0.646 1.004 0.986 1.023 Age 0.003 0.004 0.429 1 0.512 1.003 0.995 1.010 Caffeine −0.208 0.127 2.684 1 0.101 0.812 0.634 1.042 Constant −0.176 0.315 0.313 1 0.576 0.838 Note: Acculturation = level of acculturation to the US lifestyle; Alcohol = reported use of alcoholic beverages; BMI = body mass index; Caffeine = reported use of caffeinated beverages; Depression/Anxiety = prior diagnosis of depression and/or anxiety; Sleep Disorder = prior treatment for a sleep disorder. Table 5. Risk factors of poor sleep quality (Pittsburgh sleep quality index global score > 5) for non-Hispanic Whites (n = 1675). 95% CI for Exp(B) Variables in the equation B SE Wald df Sig. Exp(B) Lower Upper Depression/ anxiety 0.993 0.130 58.503 1 <0.001 2.699 2.093 3.481 Smoking 0.505 0.148 11.691 1 0.001 1.656 1.240 2.212 Sleep disorder 0.321 0.167 3.686 1 0.055 1.378 0.993 1.911 Gender 0.231 0.110 4.380 1 0.036 1.260 1.015 1.564 BMI 0.029 0.010 8.182 1 0.004 1.029 1.009 1.050 Alcohol 0.014 0.110 0.016 1 0.899 1.014 0.817 1.259 Age -0.006 0.003 3.874 1 0.049 0.994 0.988 1.000 Caffeine -0.140 0.115 1.476 1 0.224 0.869 0.694 1.090 Constant -0.279 0.352 0.629 1 0.428 0.756 Note: Alcohol = reported use of alcoholic beverages; BMI = body mass index; Caffeine = reported use of caffeinated beverages; Depression/Anxiety = prior diagnosis of depression and/or anxiety; Sleep Disorder = prior treatment for a sleep disorder. ating sleep complaints in 88,062 people from the US Be- havioral Risk Factor Surveillance System survey (4.7% Hispanics), Chowdhury et al. found that African-Ameri- cans, Hispanics and Asians were less likely to report sleep complaints compared to Caucasians [35]. Grandner et al. did a similar study with 159,856 subjects (17.4% Hispanics) and found that African-American and His- panic women and Asian men had less sleep complaints than NHW women and men respectively [36]. We did not find significant differences between HMD and NHW in their global sleep quality or in their reported sleep la- tency, sleep duration, daytime dysfunction and sleep dis- turbances as measured by the PSQI. However, a few dif- ferences were noted: NHW reported greater use of sleep medications compared to HMD, which conforms to pre- vious reports [37,38]. Potential reasons have been ad- vanced including racial/ethnic differences in the percep- tion of illness, safety and efficacy of medications, and reduced access to physicians and prescription medica- tions among minorities [39]. Another difference found in our study was that HMD also reported significantly lower sleep efficiency. The sleep efficiency of NHW was 85.6% (normal ≥ 85%), while that of HMD was signifi- cantly lower and below the clinical level of normality at 83.8%. Our findings differ from the sleep efficiency ob- served among various ethnic groups including Whites and Hispanics reported by Redline and collaborators [40]. Redline’s study showed no ethnic differences in sleep efficiency using polysomnography. The PSQI provides an average of the assessment of sleep quality over the past month while the subjects sleep in their natural envi- ronment; the polysomnogram, however, is based on one overnight study that by its nature changes and standard- izes the subjects’ usual sleep conditions thus potentially  X. SOLER ET AL. 102 explaining the finding of no ethnic difference in sleep efficiency. We did not evaluate the effect of sleep envi- ronment on sleep quality in this study, but the sleep en- vironment may be an important determinant of sleep quality as noted by the Ruiter et al.’s meta-analysis where African Americans had worse sleep continuity and duration when sleeping at home than in the sleep labora- tory [41]. According to the 2003 National Institute of Health National Sleep Disorders Research Plan, racial and ethnic minorities, and those who are socioeconomi- cally disadvantaged are more likely to sleep in less than optimal environments (e.g., too hot or too cold, noisy, or crowded) and may explain our findings [42]. We evaluated potential risk factors for poor sleep quality by multivariate analyses in HMD and NHW. A prior diagnosis of depression or anxiety was a strong risk factor for poor sleep quality in both ethnic groups. In previous work studying predictors of insomnia in breast cancer survivors, we found that of 27 potential risk fac- tors, only depression and vasomotor symptoms were sig- nificant [43]. Our results are also in agreement with mul- tiple reports that found a correlation of poor sleep quality with several factors such mood impairment, anxiety, be- ing female and ethnic groups including NHW, Afri- can-American, German, and Chinese populations [30-32]. [44-47] Buysse et al. reported that being a woman, higher scores in perceived stress, anxiety, anger, hostility and pessimism were also risk factors for poor sleep qual- ity [32]. Ramsawh et al. reported also that being a woman and anxiety were risk factors for poor sleep qual- ity [31]. Baker et al. found that poor sleep quality was associated with lifestyle, health status, and socio-demographic factors [30]. In our current study, the use of alcoholic beverages approached significance (OR 1.29, p = 0.05) as a predictor of poor sleep quality only in HMD. Recently, Ehlers et al., evaluated a group of young Hispanic men (ages 18 to 30) in San Diego County and reported that life time diagnosis of alcohol- use disorder, family history of alcohol dependence, ac- culturation stress, and lifetime diagnoses of major de- pressive disorder were all correlated with significantly poorer sleep quality as measured by the global score on the PSQI, [48] which appears to agree with our finding. Similar to our findings, some published datashow that women more frequently report poor sleep quality [49-51]. We found that both HMD and NHW women had higher prevalence of poor sleep quality as compared to men, and significantly higher mean PSQI global score. Hall et al. evaluated 370 NHW, African-American, and Chinese women and found that 66% of participants reported poor sleep quality, with African-American women reporting more complaints about sleep measured with the PSQI, similar results to current study [52]. On his study, Hall studied middle-aged women who may had been affected by physiological changes, such as menopause, which may have a high impact on sleep quality [53] and also sleep complaints that may increase with aging [54]. Studies of Hispanic immigrants and their descendants have documented higher rates of obesity [55-58], diabe- tes [55,59,60], cardiovascular disease [60-63], and psy- chiatric disorders [65,66] with increasing acculturation to the US lifestyle. Little is known of the effects of accul- turation on sleep and sleep quality. A study of middle- aged and elderly Hispanic women examined sleeping habits among other health habits and found that accul- turation negatively affected the sleep habits of mid- dle-aged but not elderly Hispanic women [67]. A study of adolescent Hispanic men (ages 11 - 19), suggested that higher levels of acculturation were associated with an increased likelihood of fewer hours of sleep per night, among other deleterious health behaviors [68]. In the current study, in the overall sample analysis, accultura- tion to the US lifestyle was not a significant predictor of sleep quality on multivariate analyses, suggesting that acculturation may be only one of many factors in the sleep quality of Hispanics living in the US [69,70]. Our findings are similar to those of Roberts et al. who found that ninth-grade-Hispanic students who identified them- selves as Mexican-Americans rather than Mexican were at a higher risk for poor sleep quality as denoted by in- somnia. However, it is an interesting observation that in the current study, on post hoc analyses, highly accultur- ated young HMD males had a significantly greater prevalence of poor sleep quality when compared to their least acculturated counterparts. Results consistent with reports from Cantero [67] and Ebin [68] suggesting that younger Latinos may be more susceptible to negative health outcomes of acculturation including poor sleep quality. Potential causes for acculturation-associated poor sleep quality include reduced hours of sleep, ir- regular sleep schedules, increased use of alcohol, tobacco, and stimulants, and the social stress needed to keep up with the busy American lifestyle [55,65,71-83]. 4.1. Limitations We endeavored to obtain the most representative sample population of HMD and NHW in San Diego County by using random digit dialing and randomization of quali- fying household adult members, which greatly increases confidence in the applicability of our findings. We also utilized professional culturally competent interviewers to conduct the study in the subject’s language of choice. However, only land lines were called. That can introduce a selection bias as many people don’t use land lines anymore, or even sometimes, they may not answer in- coming calls. It is unknown the impact to the study, fur- thermore perhaps more stay-home subjects responded the land line phone leading to a misrepresented cultural or Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OJRD  X. SOLER ET AL. 103 economic populations. Of the 3667 subjects who took the call and agreed to participate, all completed the survey. However, the sample population had to be reduced sig- nificantly, potentially reducing power, due to exclusion of cases where the subject reported logically inconsistent information about their sleep. Another limitation was the cross-sectional nature of the study, which did not allow us to make causal associations. Measurement of sleep quality using the PSQI, although subjective, may have an advantage over objective measurements of sleep quality such as polysomnography or actigraphy, since it repre- sents the subjects experience over the last 30 days rather than the sleep quality over one night or a few nights. Quality of sleep can be influenced by many other poten- tial factors that due to time constraints and subject bur- den were not evaluated in the study. 4.2. Conclusion Poor sleep quality was common and equally prevalent between HMD and NHW in a large sample of subjects living in San Diego County. Having been diagnosed of depression and/or anxiety and being a woman were strong predictors of poor sleep quality in both ethnic groups. Post hoc analyses suggested that sleep quality of young male HMD might be more susceptible to the dele- terious effects of acculturation to the US lifestyle. Fur- ther research is warranted to better understand the high prevalence of poor sleep quality among this large popu- lation and to study the role of acculturation in young HMD subjects and its certain negative health effect. 5. Key Findings Hispanics of Mexican descent and non-Hispanic Whites living in San Diego, CA, had a highly prevalent poor sleep quality. Ethnicity was not a predictor of poor sleep quality on those two racial groups. A prior diagnosis of depression or anxiety was the best predictor of poor sleep quality regardless the ethnic group. An elevated acculturation to the US lifestyle has a negative impact on sleep health in young Hispanics of Mexican descent males. 6. Acknowledgements This study was supported by NIH-HL075630 grant (JSL and XS); by AG08415 grant (SAI); and by Spanish Min- istry of Education AP 2007-02965 fellowship grant (CDP). REFERENCES [1] M. Vandekerckhove and R. Cluydts, “The Emotional Brain and Sleep: An Intimate Relationship,” Sleep Medi- cine Reviews, Vol. 14, No. 4, 2010, pp. 219-226. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2010.01.002 [2] M. D. Althuis, L. Fredman, P. W. Langenberg and J. Magaziner, “The Relationship between Insomnia and Mor- tality among Community-Dwelling Older Women,” Jour- nal of the American Geriatrics Society, Vol. 46, No. 10, 1998, pp. 1270-1273. [3] D. F. Kripke, S. Ancoli-Israel, M. R. Klauber, D. L. Wingard, W. J. Mason and D. J. Mullaney, “Prevalence of Sleep-Disordered Breathing in Ages 40 - 64 Years: A Population-Based Survey,” Sleep, Vol. 20, No. 1, 1997, pp. 65-76. [4] J. W. Shepard, Jr., “Hypertension, Cardiac Arrhythmias, Myocardial Infarction, and Stroke in Relation to Obstruc- tive Sleep Apnea,” Clinics in Chest Medicine, Vol. 13, No. 3, 1992, pp. 437-458. [5] H. Schafer, U. Koehler, S. Ewig, E. Hasper, S. Tasci and B. Luderitz, “Obstructive Sleep Apnea as a Risk Marker in Coronary Artery Disease,” Cardiology, Vol. 92, No. 2, 1999, pp. 79-84. doi:10.1159/000006952 [6] L. J. Findley, M. Fabrizio, G. Thommi and P. M. Suratt, “Severity of Sleep Apnea and Automobile Crashes,” New England Journal of Medicine, Vol. 320, No. 13, 1989, pp. 868-869. doi:10.1056/NEJM198903303201314 [7] T. Young, M. Palta, J. Dempsey, J. Skatrud, S. Weber and S. Badr, “The Occurrence of Sleep-Disordered Breathing among Middle-Aged Adults,” England Journal of Medi- cine, Vol. 328, No. 17, 1993, pp. 1230-1235. doi:10.1056/NEJM199304293281704 [8] S. D. Youngstedt, P. J. O’Connor and R. K. Dishman, “The Effects of Acute Exercise on Sleep: A Quantitative Synthesis,” Sleep, Vol. 20, No. 3, 1997, pp. 203-214. [9] G. Jean-Louis, C. Magai, G. J. Casimir, F. Zizi, F. Moise, D. McKenzie, et al., “Insomnia Symptoms in a Multieth- nic Sample of American Women,” Journal of Women’s Health, Vol. 17, No. 1, 2008, pp. 15-25. doi:10.1089/jwh.2006.0310 [10] J. Profant, S. Ancoli-Israel and J. E. Dimsdale, “Are There Ethnic Differences in Sleep Architecture?” Ameri- can Journal of Human Biology, Vol. 14, No. 3, 2002, pp. 321-326. doi:10.1002/ajhb.10032 [11] U. Rao, C. L. Hammen and R. E. Poland, “Ethnic Differ- ences in Electroencephalographic Sleep Patterns in Ado- lescents,” Asi an Journal of Psych iatry, Vol. 2, No. 1, 2009, pp. 17-24. doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2008.12.003 [12] M. E. Ruiter, J. DeCoster, L. Jacobs and K. L. Lichstein, “Sleep Disorders in African Americans and Caucasian Americans: A Meta-Analysis,” Behavioral Sleep Medi- cine, No. 4, 2010, pp. 246-259. doi:10.1080/15402002.2010.509251 [13] C. J. Stepnowsky Jr., P. J. Moore and J. E. Dimsdale, “Effect of Ethnicity on Sleep: Complexities for Epidemi- ologic Research,” Sleep, Vol. 26, No. 3, 2003, pp. 329- 332. [14] S. F. Quan, J. L. Goodwin, S. I. Babar, K. L. Kaemingk, P. L. Enright, G. M. Rosen, et al., “Sleep Architecture in normal Caucasian and Hispanic Children Aged 6 - 11 Years Recorded during Unattended Home Polysomno- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OJRD  X. SOLER ET AL. 104 graphy: Experience from the Tucson Children’s Assess- ment of Sleep Apnea Study (TuCASA),” Sleep Medicine, Vol. 4, No. 1, 2003, pp. 13-19. doi:10.1016/s1389-9457(02)00235-6 [15] P. R. Castillo, J. Kaplan, S. C. Lin, P. A. Fredrickson and M. W. Mahowald, “Prevalence of Restless Legs Syn- drome among Native South Americans Residing in Coastal and Mountainous Areas,” Mayo Clinic Proceedings, Vol. 81, No. 10, 2006, pp. 1345-1347. doi:10.4065/81.10.1345 [16] S. Shafazand, D. M. Wallace, S. S. Vargas, Y. Del Toro, S. Dib, A. R. Abreu, et al., “Sleep Disordered Breathing, Insomnia Symptoms, and Sleep Quality in a Clinical Co- hort of US Hispanics in South Florida,” Journal of Clini- cal Sleep Medicine, Vol. 8, No. 5, 2012, pp. 507-514. [17] S. Subramanian, B. Guntupalli, T. Murugan, S. Bopparaju, S. Chanamolu, L. Casturi, et al., “Gender and Ethnic Dif- ferences in Prevalence of Self-Reported Insomnia among patients with Obstructive Sleep Apnea,” Sleep & Breath- ing, Vol. 15, No. 4, 2011, pp. 711-715. doi:10.1007/s11325-010-0426-4 [18] L. Tomfohr, M. A. Pung, K. M. Edwards and J. E. Dims- dale, “Racial Differences in Sleep Architecture: The Role of Ethnic Discrimination,” Biological Psychology, Vol. 89, No. 1, 2012, pp. 34-38. doi:10.1016/j.biopsycho.2011.09.002 [19] Y. Song, X. Zhang, J. Ma, B. Zhang, P. J. Hu and B. Dong, “Behavioral Risk Factors for Overweight and Obe- sity among Chinese Primary and Middle School Students in 2010,” Chinese Journal of Preventive Medicine, Vol. 46, No. 9, 2012, pp. 789-795. [20] K. Ladenheim, “Collecting from the Uninsured: Hospital Billing Practices,” NCSL Legisbrief, Vol. 14, No. 34, 2006, pp. 1-2. [21] B. Guzman and E. D. McConnell, “The Hispanic popula- tion: 1990-2000 Growth and Change,” Population Re- search and Policy Review, Vol. 21, No. 1-2, 2002, pp. 109- 128. doi:10.1023/A:1016541906218 [22] L. E. Skolarus, L. D. Lisabeth, L. B. Morgenstern, W. Burgin and D. L. Brown, “Sleep Apnea Risk among Mexican American and Non-Hispanic White Stroke Sur- vivors,” A Journal of Cerebral Circulation, Vol. 43, No. 4, 2012, pp. 1143-1145. [23] M. R. Benjamins, J. Hirschman, J. Hirschtick and S. Whitman, “Exploring Differences in Self-Rated Health among Blacks, Whites, Mexicans, and Puerto Ricans,” Ethnicity & Health, Vol. 17, No. 5, 2012, pp. 463-476. doi:10.1080/13557858.2012.654769 [24] J. Waksberg, “Sampling Methods for Random Digit Di- aling,” Journal of the American Statistical Association, Vol. 73, No. 361, 1978, pp. 40-46. doi:10.1080/01621459.1978.10479995 [25] G. Marin, F. Sabogal, B. V. Marin, R. Otero-Sabogal and E. J. Perez-Stable, “Development of a Short Acculturation Scale for Hispanics,” Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 9, No. 2, 1987, pp. 183-205. doi:10.1177/07399863870092005 [26] D. J. Buysse, C. F. Reynolds, 3rd, T. H. Monk, S. R. Berman and D. J. Kupfer, “The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: A New Instrument for Psychiatric Practice and Research,” Psychiatry Research, Vol. 28, No. 2, 1989, pp. 193-213. doi:10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4 [27] A. M. J. Royuela, “Propiedades Clinimétricas de la Versión Castellana del Cuestionario de Pittsburgh,” Vigilia-Sueño, No. 9, 1997, pp. 81-94. [28] F. Escobar-Cordoba and J. Eslava-Schmalbach, “Colom- bian validation of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index,” Revista de Neurologia, Vol. 40, No. 3, 2005, pp. 150-155. [29] A. Jimenez-Genchi, E. Monteverde-Maldonado, A. Nen- clares-Portocarrero, G. Esquivel-Adame and A. de la Vega-Pacheco, “Reliability and Factorial Analysis of the Spanish Version of the Pittsburg Sleep Quality Index among Psychiatric Patients,” Gaceta medica de Mexico, Vol. 144, No. 6, 2008, pp. 491-496. [30] F. C. Baker, A. R. Wolfson and K. A. Lee, “Association of Sociodemographic, Lifestyle, and Health Factors with Sleep Quality and Daytime Sleepiness in Women: Find- ings from the 2007 National Sleep Foundation ‘Sleep in America Poll’,” Journal of Women’s Health (Larchmt), Vol. 18, No. 6, 2009, pp. 841-849. doi:10.1089/jwh.2008.0986 [31] H. J. Ramsawh, M. B. Stein, S. L. Belik, F. Jacobi and J. Sareen, “Relationship of Anxiety Disorders, Sleep Qual- ity, and Functional Impairment in a Community Sample,” Journal of Psychiatric Research, Vol. 43, No. 10, 2009, pp. 926-933. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2009.01.009 [32] D. J. Buysse, M. L. Hall, P. J. Strollo, T. W. Kamarck, J. Owens, L. Lee, et al., “Relationships between the Pitts- burgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), and Clinical/Polysomnographic Measures in a Community Sample,” Journal of Clinical Sleep Medi- cine, Vol. 4, No. 6, 2008, pp. 563-571. [33] E. J. Mezick, K. A. Matthews, M. Hall, P. J. Strollo, Jr., D. J. Buysse, T. W. Kamarck, et al., “Influence of Race and Socioeconomic Status on Sleep: Pittsburgh Sleep SCORE Project,” Psychosomatic Medicine, Vol. 70 No. 4, 2008, pp. 410-416. doi:10.1097/PSY.0b013e31816fdf21 [34] National Sleep Foundation, “2010 Sleep in America Poll.” http://www.sleepfoundation.org/article/sleep-america-poll s/2010-sleep-and-ethnicity [35] P. P. Chowdhury, L. Balluz and T. W. Strine, “Health- Related Quality of Life among Minority Populations in the United States, BRFSS 2001-2002,” Ethnicity & Dis- ease, Vol. 18, No. 4, 2008, pp. 483-487. [36] M. A. Grandner, N. P. Patel, P. R. Gehrman, D. Xie, D. Sha, T. Weaver, et al., “Who Gets the Best Sleep? Ethnic and Socioeconomic Factors Related to Sleep Complaints,” Sleep Medicine, Vol. 11, No. 5, 2010, pp. 470-478. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2009.10.006 [37] S. Ram, H. Seirawan, S. K. Kumar and G. T. Clark, “Prevalence and Impact of Sleep Disorders and Sleep Habits in the United States,” Sleep & Breathing, Vol. 14, No. 1, 2010, pp. 63-70. doi:10.1007/s11325-009-0281-3 [38] E. P. Cherniack, J. Ceron-Fuentes, H. Florez, L. Sandals, O. Rodriguez and J. C. Palacios, “Influence of Race and Ethnicity on Alternative Medicine as a Self-Treatment Preference for Common Medical Conditions in a Popula- tion of Multi-Ethnic Urban Elderly,” Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, Vol. 14, No. 2, 2008, pp. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OJRD  X. SOLER ET AL. 105 116-123. doi:10.1016/j.ctcp.2007.11.002 [39] M. A. Clark, M. L. Rogers and S. M. Allen, “Conducting Telephone Interviews with Community-Dwelling Older Adults in a State Medicaid Program: Differences by Eth- nicity and Language Preference,” Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, Vol. 21, No. 4, 2010, pp. 1304-1317. [40] S. Redline, H. L. Kirchner, S. F. Quan, D. J. Gottlieb, V. Kapur and A. Newman, “The Effects of Age, Sex, Eth- nicity, and Sleep-Disordered Breathing on Sleep Archi- tecture,” Archives of Internal Medicine, Vol. 164, No. 4, 2004, pp. 406-418. doi:10.1001/archinte.164.4.406 [41] M. E. Ruiter, J. Decoster, L. Jacobs and K. L. Lichstein, “Normal Sleep in African-Americans and Caucasian- Americans: A Meta-Analysis,” Sleep Medicine, Vol. 12, No. 3, 2011, pp. 209-214. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2010.12.010 [42] “2003 National Sleep Disorders Research Plan,” Sleep, Vol. 26, No. 3, 2003, pp. 253-257. [43] W. A. Bardwell, J. Profant, D. R. Casden, J. E. Dimsdale, S. Ancoli-Israel, L. Natarajan, C. L. Rock, J. P. Pierce, and Women’s Healthy Eating & Living (WHEL) Study Group, “The Relative Importance of Specific Risk Factors for Insomnia in Women Treated for Early-Stage Breast Cancer,” Psychooncology, Vol. 17, No. 1, 2008, pp. 9-18. [44] M. M. Ohayon, “Epidemiology of Insomnia: What We Know and What We Still Need to Learn,” Sleep Medicine Reviews, Vol. 6, No. 2, 2002, pp. 97-111. doi:10.1053/smrv.2002.0186 [45] O. Dogan, S. Ertekin and S. Dogan, “Sleep Quality in Hospitalized Patients,” Journal of Clinical Nursing, Vol. 14, No. 1, 2005, pp. 107-113. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2004.01011.x [46] J. F. Owens and K. A. Matthews, “Sleep Disturbance in Healthy Middle-Aged Women,” Maturitas, Vol. 30, No. 1, 1998, pp. 41-50. doi:10.1016/S0378-5122(98)00039-5 [47] A. G. Wheaton, G. S. Perry, D. P. Chapman and J. B. Croft, “Sleep Disordered Breathing and Depression among US Adults: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2005-2008,” Sleep, Vol. 35, No. 4, 2012, pp. 461-467. [48] C. L. Ehlers, D. A. Gilder, J. R. Criado and R. Caetano, “Sleep Quality and Alcohol-Use Disorders in a Select Population of Young-Adult Mexican Americans,” Jour- nal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, Vol. 71, No. 6, 2010, pp. 879-884. [49] A. Dzaja, S. Arber, J. Hislop, M. Kerkhofs, C. Kopp, T. Pollmacher, et al., “Women’s Sleep in Health and Dis- ease,” Journal of Psychiatric Research, Vol. 39, No. 1, 2005, pp. 55-76. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2004.05.008 [50] M. L. Unruh and S. Redline, M. W. An, D. J. Buysse, F. J. Nieto, J. L. Yeh, et al., “Subjective and Objective Sleep Quality and Aging in the Sleep Heart Health Study,” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, Vol. 56, No. 7, 2008, pp. 1218-1227. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01755.x [51] B. Zhang and Y. K. Wing, “Sex Differences in Insomnia: A Meta-Analysis,” Sleep, Vol. 29, No. 1, 2006, pp. 85-93. [52] M. H. Hall, K. A. Matthews, H. M. Kravitz, E. B. Gold, D. J. Buysse, J. T. Bromberger, et al., “Race and Finan- cial Strain Are Independent Correlates of Sleep in Midlife Women: The SWAN Sleep Study,” Sleep, Vol. 32, No. 1, 2009, pp. 73-82. [53] H. Hachul, M. L. Andersen, L. R. A. Bittencourt, R. San- tos-Silva, S. G. Conway and S. Tufik, “Does the Repro- ductive Cycle Influence Sleep Patterns in Women with Sleep Complaints?” Climacteric, Vol. 13, No. 6, 2010, pp. 594-603. doi:10.3109/13697130903450147 [54] M. M. Ohayon, M. A. Carskadon, C. Guilleminault and M. V. Vitiello, “Meta-Analysis of Quantitative Sleep Pa- rameters from Childhood to Old Age in Healthy Indi- viduals: Developing Normative Sleep Values across the Human Lifespan,” Sleep, Vol. 27, No. 7, 2004, pp. 1255- 1273. [55] H. P. Hazuda, S. M. Haffner, M. P. Stern and C. W. Eifler, “Effects of Acculturation and Socioeconomic Status on Obesity and Diabetes in Mexican Americans. The San Antonio Heart Study,” American Journal of Epidemiol- ogy, Vol. 128, No. 6, 1988, pp. 1289-1301. [56] I. G. Pawson, R. Martorell and F. E. Mendozam, “Preva- lence of Overweight and Obesity in US Hispanic Popula- tions,” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, Vol. 53, Suppl. 6, 1991, pp. 1522S-1528S. [57] L. K. Khan, J. Sobal and R. Martorell, “Acculturation, Socioeconomic Status, and Obesity in Mexican Ameri- cans, Cuban Americans, and Puerto Ricans,” Interna- tional Journal of Obesity and Related Metabolic Disor- ders, Vol. 21, No. 2, 1997, pp. 91-96. doi:10.1038/sj.ijo.0800367 [58] J. Sundquist and M. Winkleby, “Country of Birth, Accul- turation Status and Abdominal Obesity in a National Sample of Mexican-American Women and Men,” Inter- national Journal of Epidemiology, Vol. 29, No. 3, 2000, pp. 470-477. doi:10.1093/ije/29.3.470 [59] J. M. Samet, D. B. Coultas, C. A. Howard, B. J. Skipper and C. L. Hanis, “Diabetes, Gallbladder Disease, Obesity, and Hypertension among Hispanics in New Mexico,” American Journal of Epidemiology, Vol. 128, No. 6, 1988, pp. 1302-1311. [60] M. P. Stern, J. A. Knapp, H. P. Hazuda, S. M. Haffner, J. K. Patterson and B. D. Mitchell, “Genetic and Environ- mental Determinants of Type II Diabetes in Mexican Americans. Is There a ‘Descending Limb’ to the Mod- ernization/Diabetes Relationship?” Diabetes Care, Vol. 14, No. 7, 1991, pp. 649-654. doi:10.2337/diacare.14.7.649 [61] J. Sundquist and M. A. Winkleby, “Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Mexican American Adults: A Transcultural Analysis of NHANES III, 1988-1994,” American Journal of Public Health, Vol. 89, No. 5, 1999, pp. 723-730. doi:10.2105/AJPH.89.5.723 [62] P. W. Goslar, C. A. Macera, L. G. Castellanos, J. R. Hussey, F. S. Sy and P. A. Sharpe, “Blood Pressure in Hispanic Women: The Role of Diet, Acculturation, and Physical Activity,” Ethnicity & Disease, Vol. 7, No. 2, 1997, pp. 106-113. [63] C. J. Crespo, C. M. Loria and V. L. Burt, “Hypertension Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OJRD  X. SOLER ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OJRD 106 and Other Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors among Mexican Americans, Cuban Americans, and Puerto Ri- cans from the Hispanic Health and Nutrition Examination Survey,” Public Health Reports, Vol. 111, Suppl. 2, 1996, pp. 7-10. [64] M. P. Stern, M. Rosenthal, S. M. Haffner, H. P. Hazuda and L. J. Franco, “Sex Difference in the Effects of So- ciocultural Status on Diabetes and Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Mexican Americans. The San Antonio Heart Study,” American Journal of Epidemiology, Vol. 120, No. 6, 1984, pp. 834-851. [65] M. A. Burnam, R. L. Hough, M. Karno, J. I. Escobar and C. A. Telles, “Acculturation and Lifetime Prevalence of Psychiatric Disorders among Mexican Americans in Los Angeles,” Journal of Health and Social Behavior, Vol. 28, No. 1, 1987, pp. 89-102. doi:10.2307/2137143 [66] E. Alderete, W. A. Vega, B. Kolody and S. Aguilar- Gaxiola, “Effects of Time in the United States and Indian Ethnicity on DSM-III-R Psychiatric Disorders among Mexican Americans in California,” Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, Vol. 188, No. 2, 2000, pp. 90-100. doi:10.1097/00005053-200002000-00005 [67] P. J. Cantero, J. L. Richardson, L. Baezconde-Garbanati and G. Marks, “The Association between Acculturation and Health Practices among Middle-Aged and Elderly Latinas,” Ethnicity & Disease, Vol. 9, No. 2, 1999, pp. 166-80. [68] V. J. Ebin, C. D. Sneed, D. E. Morisky, M. J. Rothe- ram-Borus, A. M. Magnusson and C. K. Malotte, “Ac- culturation and Interrelationships between Problem and Health-Promoting Behaviors among Latino Adolescents,” Journal of Adolescent Health, Vol. 28, No. 1, 2001, pp. 62-72. doi:10.1016/S1054-139X(00)00162-2 [69] R. E. Roberts and E. S. Lee, “The Health of Mexican Americans: Evidence from the Human Population Labo- ratory Studies,” American Journal of Public Health, Vol. 70, No. 4, 1980, pp. 375-384. doi:10.2105/AJPH.70.4.375 [70] R. E. Roberts, E. S. Lee, M. Hemandez and A. C. Solari, “Symptoms of Insomnia among Adolescents in the Lower Rio Grande Valley of Texas,” Sleep, Vol. 27, No. 4, 2004, pp. 751-760. [71] E. Alderete, W. A. Vega, B. Kolody and S. Aguilar- Gaxiola, “Lifetime Prevalence of and Risk Factors for Psychiatric Disorders among Mexican Migrant Farm- workers in California,” American Journal of Public Health, Vol. 90, No. 4, 2000, pp. 608-614. doi:10.2105/AJPH.90.4.608 [72] O. I. Bermudez, L. M. Falcon and K. L. Tucker, “Intake and Food Sources of Macronutrients among Older His- panic Adults: Association with Ethnicity, Acculturation, and Length of Residence in the United States,” Journal of the American Dietetic Association, Vol. 100, No. 6, 2000, pp. 665-673. doi:10.1016/S0002-8223(00)00195-4 [73] R. Caetano and M. E. Mora, “Acculturation and Drinking among People of Mexican Descent in Mexico and the United States,” Journal of Studies on Alcohol, Vol. 49, No. 5, 1988, pp. 462-471. [74] J. P. Elder, F. G. Castro, C. de Moor, J. Mayer, J. I. Can- delaria, N. Campbell, et al., “Differences in Cancer- Risk-Related Behaviors in Latino and Anglo Adults,” Preventive Medicine, Vol. 20, No. 6, 1991, pp. 751-763. doi:10.1016/0091-7435(91)90069-G [75] D. V. Espino and D. Maldonado, “Hypertension and Ac- culturation in Elderly Mexican Americans: Results from 1982-84 Hispanic HANES,” Journal of Gerontology, Vol. 45, No. 6, 1990, pp. M209-M213. doi:10.1093/geronj/45.6.M209 [76] G. Marin, E. J. Perez-Stable and B. V. Marin, “Cigarette Smoking among San Francisco Hispanics: The Role of Acculturation and Gender,” American Journal of Public Health, Vol. 79, No. 2, 1989, pp. 196-198. doi:10.2105/AJPH.79.2.196 [77] K. S. Markides, N. Krause and C. F. Mendes de Leon, “Acculturation and Alcohol Consumption among Mexi- can Americans: A Three-Generation Study,” American Journal of Public Health, Vol. 78, No. 9, 1988, pp. 1178- 1181. doi:10.2105/AJPH.78.9.1178 [78] R. Otero-Sabogal, F. Sabogal, E. J. Perez-Stable and R. A. Hiatt, “Dietary Practices, Alcohol Consumption, and Smoking Behavior: Ethnic, Sex, and Acculturation Dif- ferences,” Journal of the National Cancer Institute. Mono- graphs, No. 18, 1995, pp. 73-82. [79] L. A. Palinkas, J. Pierce, B. P. Rosbrook, S. Pickwell, M. Johnson and D. G. Bal, “Cigarette Smoking Behavior and Beliefs of Hispanics in California,” American Journal of Preventive Medicine, Vol. 9, No. 6, 1993, pp. 331-337. [80] R. E. Roberts and E. S. Lee, “Medical Care Use by Mexi- can-Americans: Evidence from the Human Population Laboratory Studies,” Medical Care, Vol. 18, No. 3, 1980, pp. 267-281. doi:10.1097/00005650-198003000-00002 [81] J. M. Solis, G. Marks, M. Garcia and D. Shelton, “Accul- turation, Access to Care, and Use of Preventive Services by Hispanics: Findings from HHANES 1982-84,” Ameri- can Journal of Public Health, Vol. 80, Supplement, 1990, pp. 11-19. doi:10.2105/AJPH.80.Suppl.11 [82] K. B. Wells, J. M. Golding, R. L. Hough, M. A. Burnam and M. Karno, “Factors Affecting the Probability of Use of General and Medical Health and Social/Community Services for Mexican Americans and Non-Hispanic Whites,” Medical Care, Vol. 26, No. 5, 1988, pp. 441- 452. doi:10.1097/00005650-198805000-00001 [83] M. A. Winkleby, S. P. Fortmann and B. Rockhill, “Health- Related Risk Factors in a Sample of Hispanics and Whites Matched on Sociodemographic Characteristics. The Stanford Five-City Project,” American Journal of Epidemiology, Vol. 137, No. 12, 1993, pp. 1365-1375.

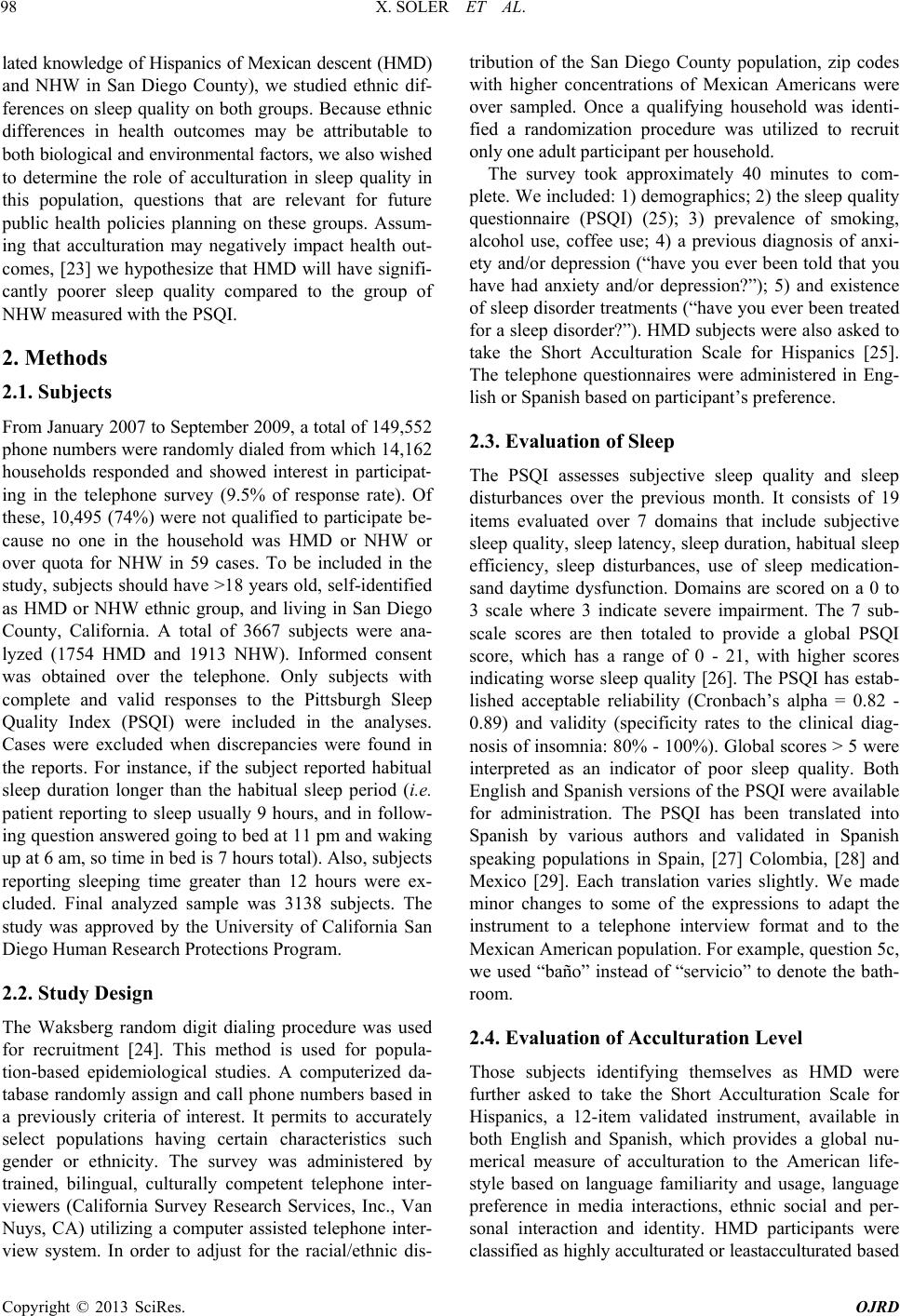

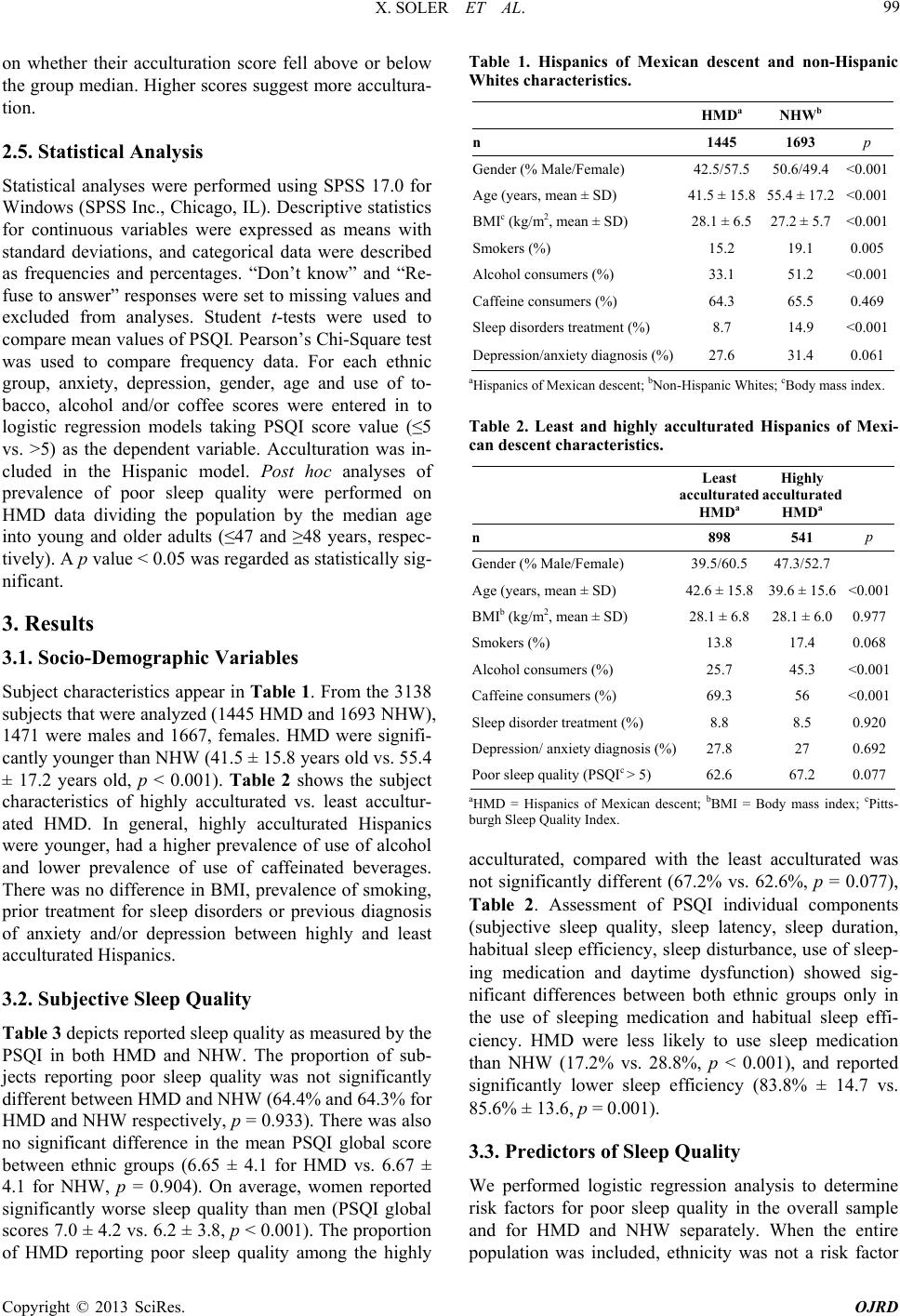

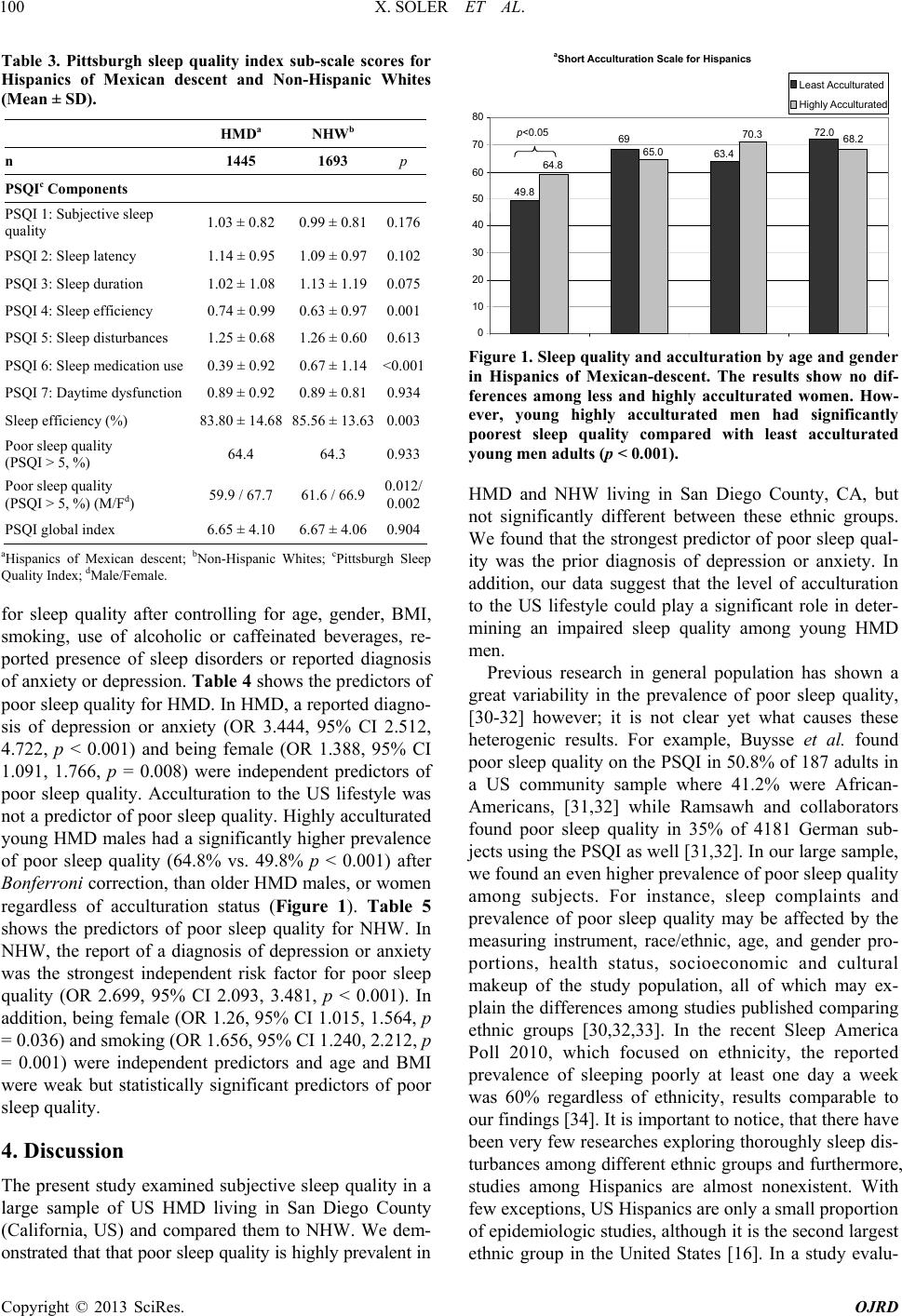

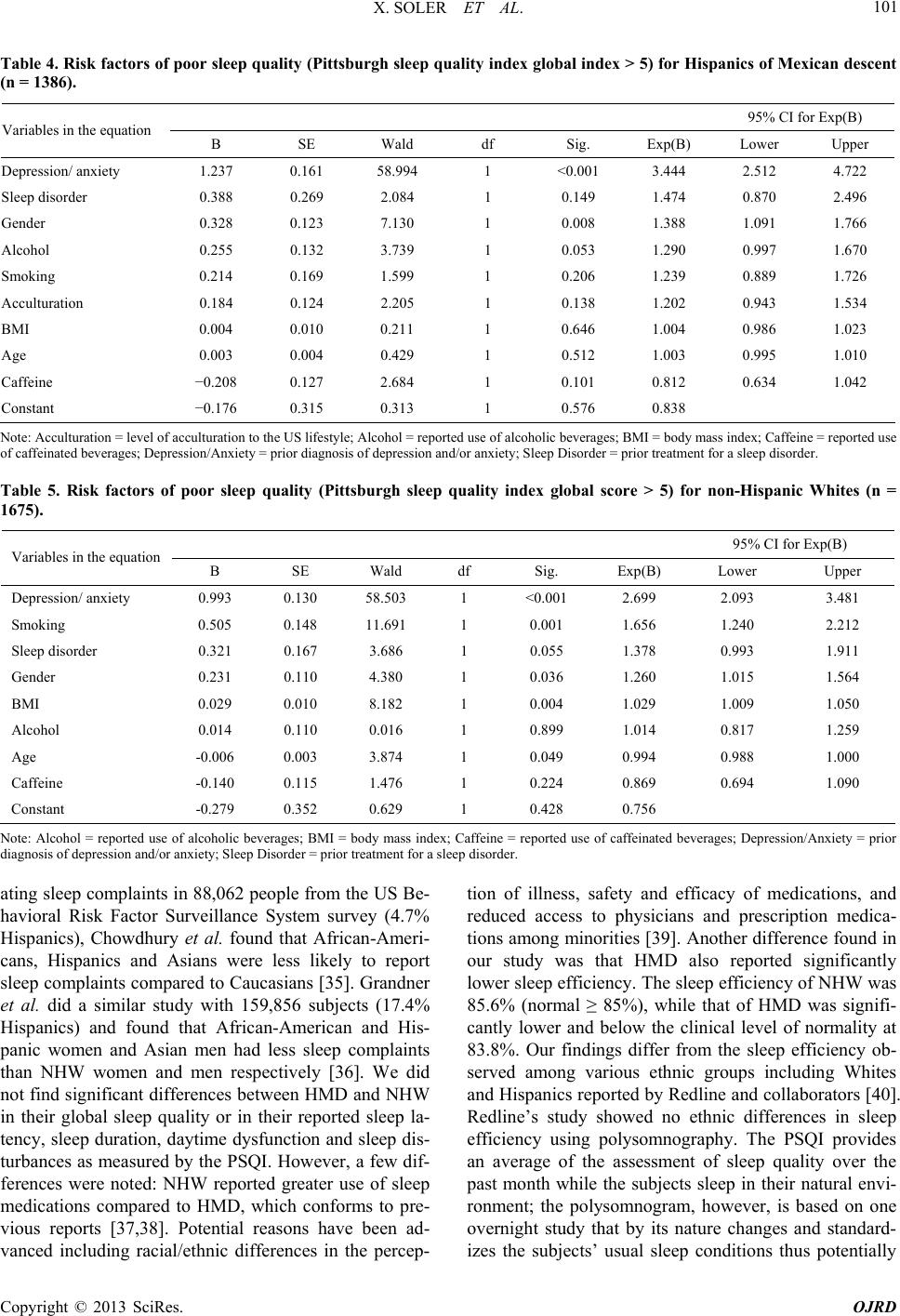

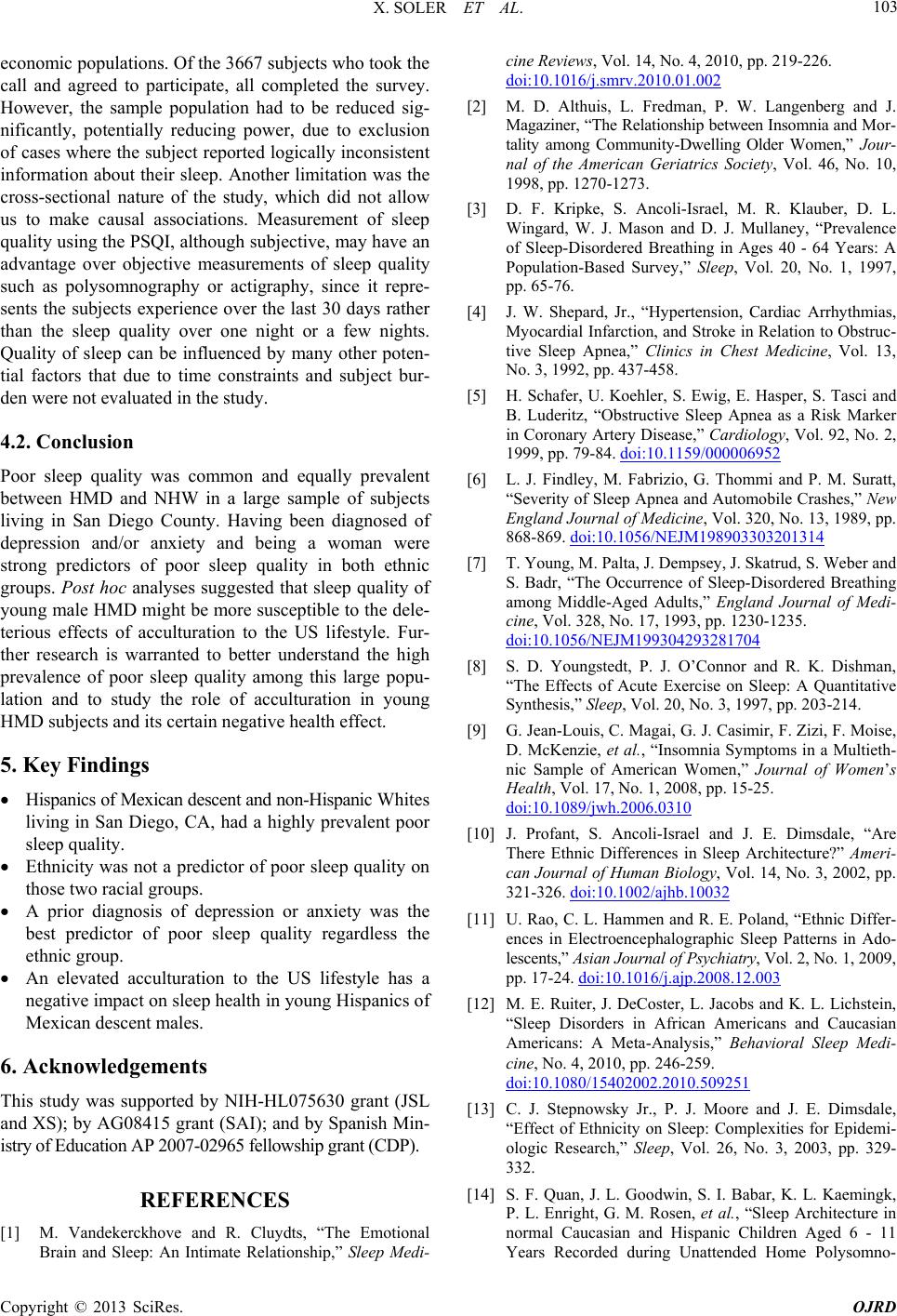

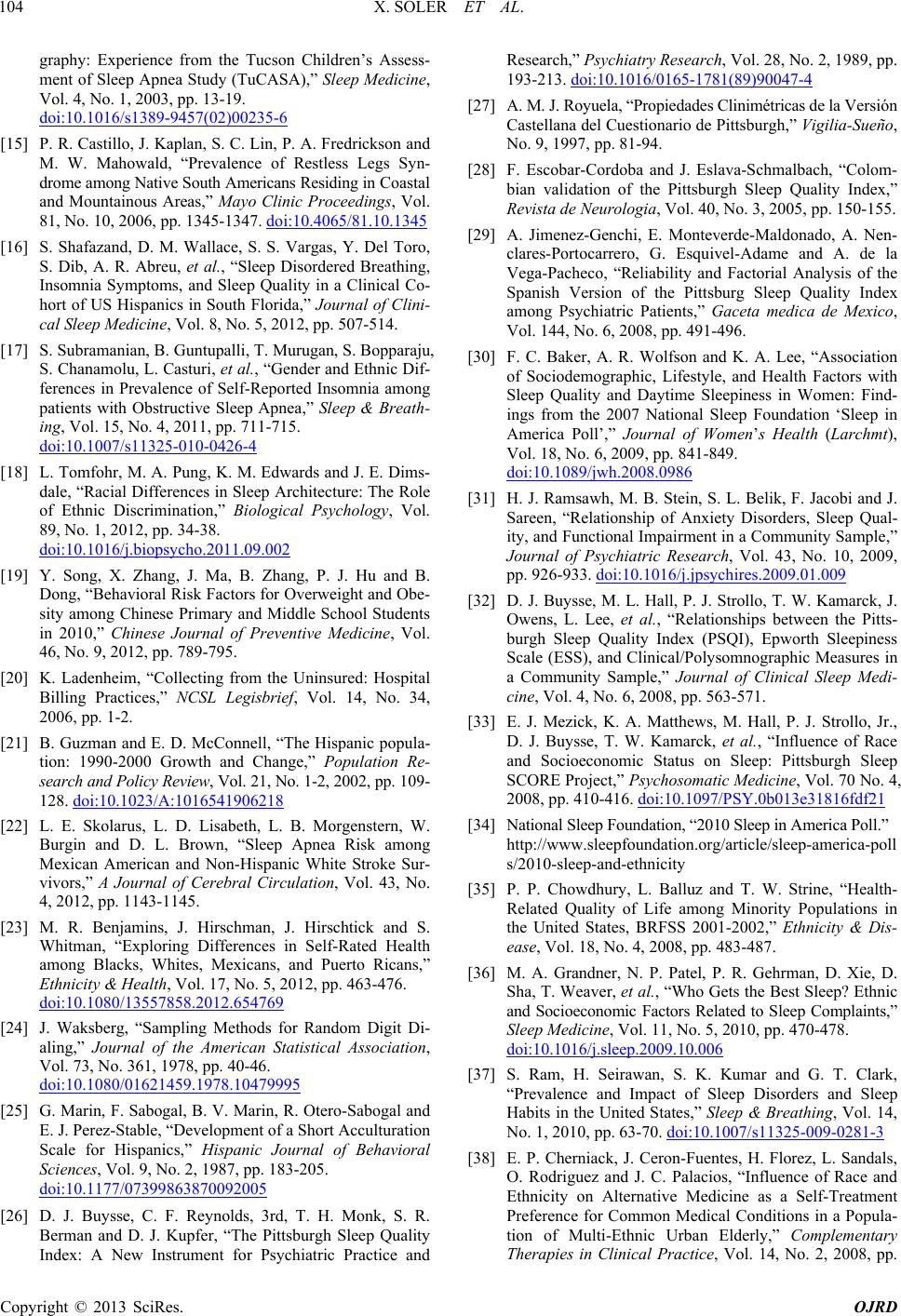

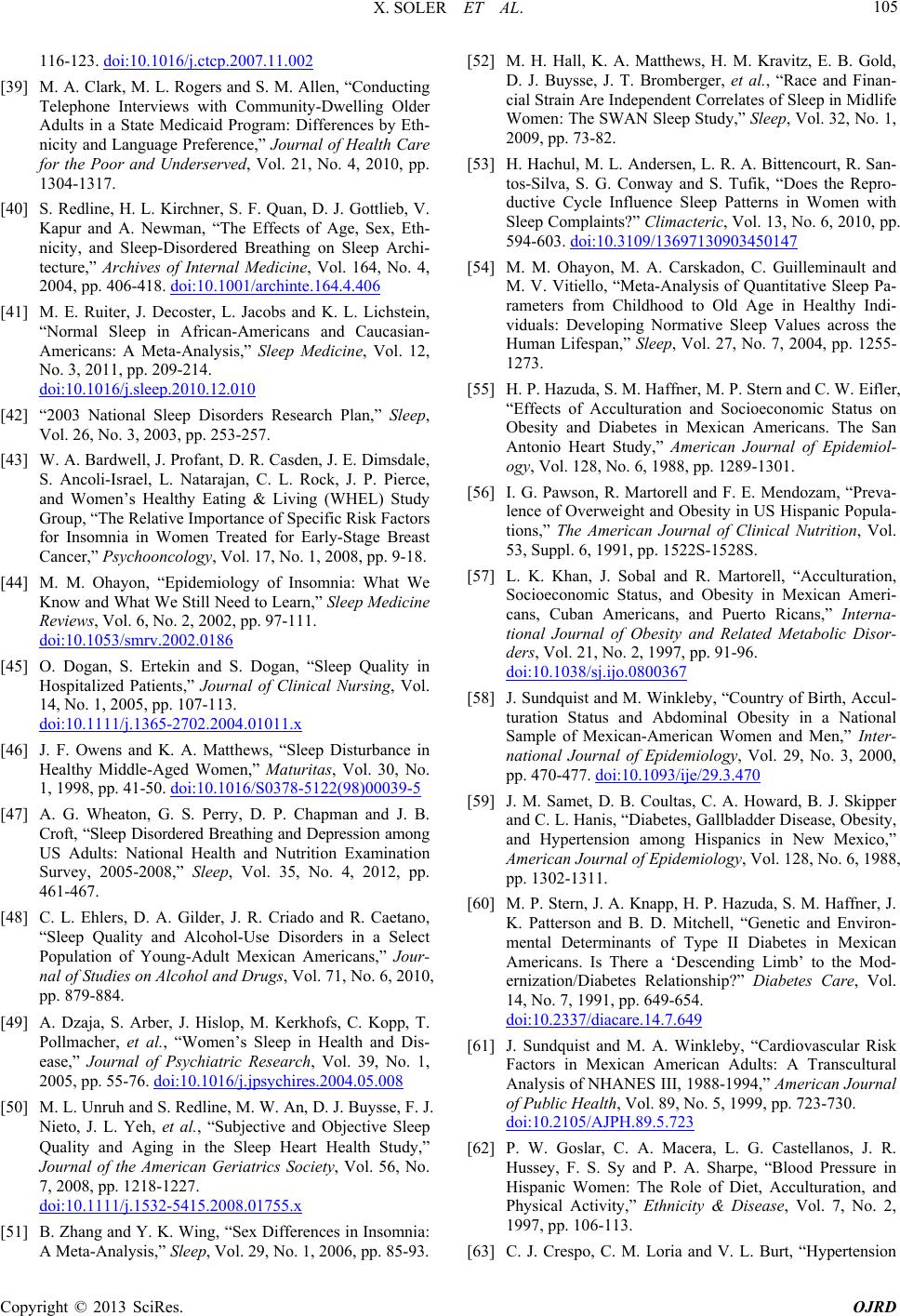

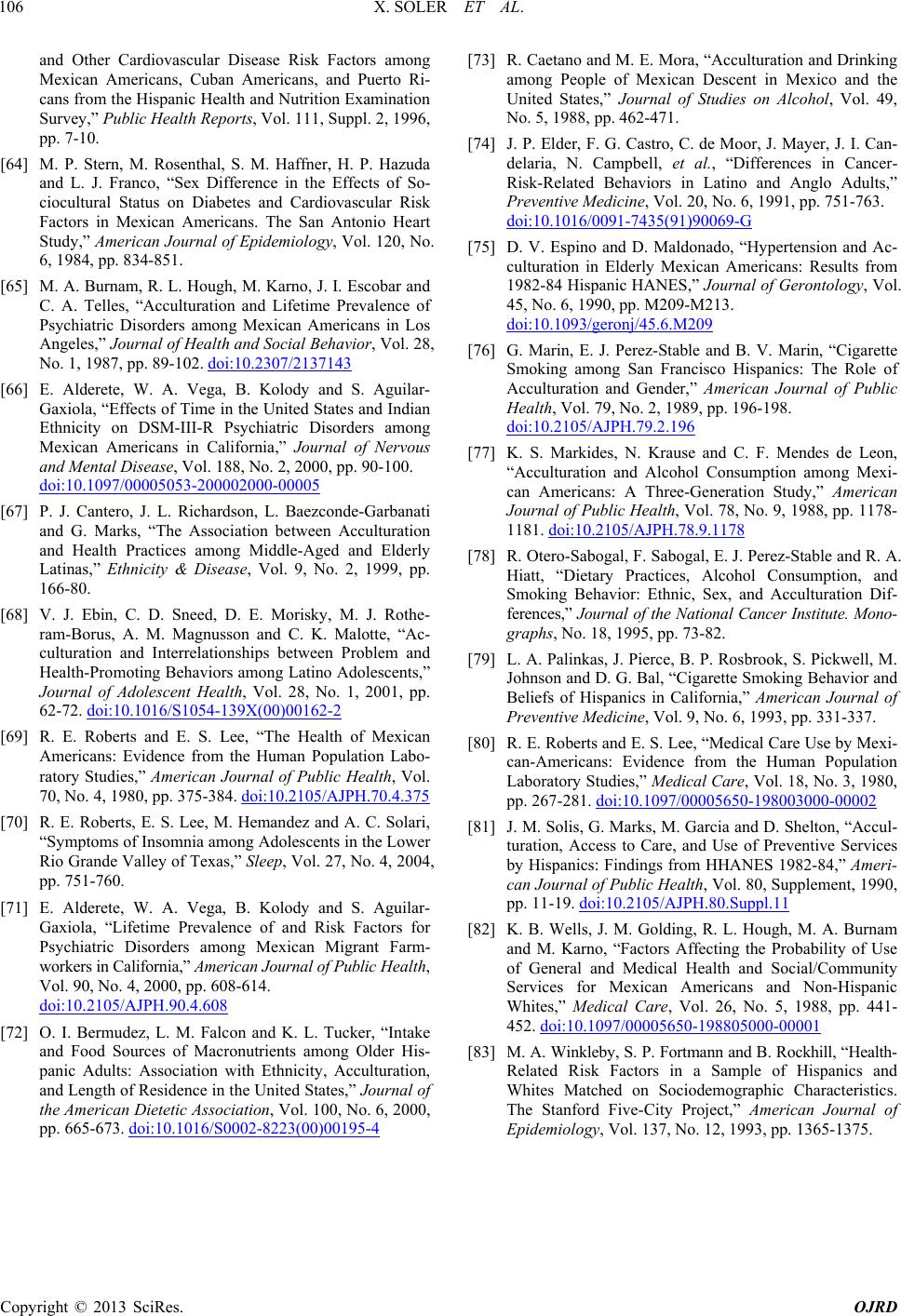

|