Advances in Anthropology 2013. Vol.3, No.2, 101-111 Published Online May 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/aa) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/aa.2013.32014 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 101 DNA Genealogy and Linguistics. Ancient Europe Anatole A. Klyosov1, Giancarlo T. Tomezzoli2 1The Academy of DNA Genealogy, Newton, USA 2European Patent Office, Munich, Germany Email: aklyosov@comcast.net, gtomezzoli@epo.org Received March 19th, 2013; revised April 20th, 2013; accepted April 27th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Anatole A. Klyosov, Giancarlo T. Tomezzoli. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. This article attempts to merge the data of contemporary linguistics and DNA genealogy in order to de- scribe the migrations and settlement of peoples and languages in Europe after the last Ice Age. In the new paradigm, three important groups of players have been identified: —R1a haplogroup bearers, condition- ally identified as Aryans. They arose around 20,000 years before the present (ybp) in central Asia and the Altai Mountains; after their migration along the southern route, they arrived in Europe between 10,000 - 9000 ybp, bringing proto-Indo European (PIE) and Indo European (IE) languages. In 4800 ybp they mi- grated eastward from Europe to the Russian Plane and then to India. About 3000 - 2500 ybp they mi- grated with their IE languages from the Russian Plain back to central, western, and southern Europe, lay- ing the genetic groundwork for peoples later called Celts, Germans, Italics, Greeks, Illyrians, and Balto-Slavs. —E, F, G, J, I, K haplogroup bearers. The dates of their arrival in Europe (sometime before 5000 ybp) and their migration routes remain obscure. They apparently spoke non-IE languages. —R1b haplogroup bearers, called the Arbins. They arose about 16,000 ybp in central Asia, and migrated to Europe along a northern route. They arrived in Europe between 4800 and 4500 ybp bringing with them several non-IE languages. It seems that the arrival of the Aryans (R1a) in Europe was peaceful. There are no clear indica- tions that their arrival triggered any sort of violence. However, the migration of the Arbins (R1b) was marked by an almost complete elimination of the E1b, F, G2a, J, I1, I2, and K haplogroups from Europe. Our analysis of current linguistic theories in the light of DNA genealogy data demonstrates that: —the Anatolian theory is generally compatible with DNA genealogy data; —the Vasconic and Afro-asiatic substratum theory is partially in agreement with DNA genealogy data; —the Kurgan theory and the Pa- laeolithic Continuity Theory (PCT) appear incompatible with the history of Europe based on haplogroup data. —the “Out of Africa” theory has questionable validity. Keywords: Y Chromosome; Mutations; Haplotypes; Haplogroups; SNP; Linguistics; Anatolian Theory; Vasconic; Kurgan; Palaeolithic Continuity Introduction DNA genealogy is an historical science that allows research- ers to trace the migration and evolution of populations. DNA genealogy studies the molecular history of DNA by analyzing the mutations in the Y chromosome (in males) and in the mtDNA (in males and females). The haplotypes of the Y chro- mosome are rather accurate tools; for example, using 111- marker haplotypes resolves DNA-lineages down to 5-genera- tion increments; mtDNA is a much cruder tool, and its resolu- tion stops at a few thousand years. Many distinct linguistic theories have attempted to pin down when ancient populations speaking different languages settled in Europe after the last Ice Age. These theories offer supporting arguments, discuss the interrelationships with other theories, and often contest, contradict, or reject aspects of other linguistic theories concerning the settlement of ancient Europe. In this paper, we 1) establish a reasonable migration/linguistic/settle- ment paradigm for ancient Europe from the Paleolithic to the Common Era, and 2) summarize the major linguistic theories of the last 120 years. Then, using the tools of DNA genealogy, we 3) compare our results with the hypotheses of the linguistic theories. Ancient Migrations to, from, and wi thin Europe as Revealed by DN A Genealogy The α-haplogroup of the Y-chromosome (cf. Figure 1), which is present in almost all males living today (except certain archaic African lineages A0, A00, etc., not shown in Figure 1, since their dating is still uncertain), arose around 160,000 ybp (Klyosov & Rozhanskii, 2012a) in a location currently un- known. Essentially, the α-haplogroup was carried by the com- mon ancestor of what we think of as anatomically modern man. We can only conjecture where that common ancestor might have lived; it seems that he could have lived in the vast triangle from Central Europe and Ireland to the west, through the Rus- sian Plain to the east, to the Levant in the south (Klyosov & Rozhanskii, 2012a). This huge area is defined by the greatest number of ancient skeletal fragments of anatomically modern homo sapiens (AMH) found in Europe (dated between 45,000 - 43,000 ybp) (Benazzi et al., 2011; Higham et al., 2011), and in the Russian Plains of eastern Europe (dated between 40,000 and  A. A. KLYOSOV, G. T. TOMEZZOLI Figure 1. Haplogroup tree of the H. sapiens Y-chromosome derived from haplotypes and subclades (Klyosov & Rozhanskii, 2012a). The African branch is on the left, the non-African one is on the right. The diagram was composed using 7415 haplotypes from 46 subclades of 17 major haplogroups. The timescale on the vertical axis shows thousands of years from the common ancestors of the haplogroups and subclades. 35,000 ybp or even between 45,000 and 42,000 ybp, when op- tically stimulated luminescence dating of the settlements is used) (Prat et al., 2011; Anikovich et al., 2007). Figure 1 shows the estimated dates of the occurrence of hu- man haplogroups (Klyosov & Rozhanskii, 2012a). To compose this tree, we analyzed 7415 haplotypes from 46 subclades of 17 major haplogroups. The α-haplogroup, which is ancestral to both the African and non-African haplogroups, arose about 160,000 ybp. The left branch represents current African hap- logroups, which arose 160,000 - 140,000 ybp. The non-African β-branch arose ~64,000 ybp; β and its descendants were not descendants of the African branch but share a common ancestor. Haplogroups F through T represent Europeoids (Caucasoids) who arose ~58,000 ybp (Klyosov & Rozhanskii, 2012a). Some contemporary Africans are bearers of recently discov- ered haplogroups A0, A00, etc. which arose some 200,000 - 260,000 years ybp, or even earlier (Mendez et al., 2013). These might be the only truly African haplogroups. With respect to mutation, they are very distant from other haplogroup A haplo- types. This study concentrates on the haplogroups on the right-hand side of the diagram in Figure 1. Two of them, R1a and R1b, descended from the R1 haplogroup, which is shown in Figure 1. R1a is the group, conditionally called the Aryans, which em- braces about 50% of the current population of Eastern Europe. This group has the same DNA as the legendary Aryans, who arrived to India around 3500 ybp. Currently, approximately 72% of the some upper Indian castes belong to the R1a haplogroup (Sharma et al., 2009). Haplogroup R1a apparently arose about 20,000 ybp (Klyosov & Rozhanskii, 2012b) in central Asia and possibly in the southern Siberia region of the Altai Mountains. Its ancient sub- clade M17 is observed in north China (Klyosov, 2009). R1a bearers migrated from central Asia across Tibet, Hindustan, the Iranian Plateau, and Anatolia between 12,000 and 10,000 ybp. Their downstream subclade, M417, crossed Asia Minor and en- tered the Balkans between 10,000 and 8000 ybp. It is appar- ently their arrival in the Balkans which strontium isotope mea- surements dated at 8200 ybp (Boric & Price, 2013). The M417 subclade spread all over Europe sometime between 9000 and 5000 ybp. Around 5700 ybp, the recently discovered Z645 branch of haplogroup R1a developed. In 4900 ybp (Rozhanskii & Klyosov, 2012), we find a Eurasian branch, Z283, and its South-Eastern branch Z93, along with the downstream branch Z342.2/Z94 and the central Eurasian branch Z280. The central Eurasian branch R1a-Z280 embraces about half of all contem- porary east European males, and the Aryan branch R1a-Z94 is currently observed in Russians, Ukrainians, and in southern Asian populations in like the Kyrgyz, the Kazakh, and the Tajik peoples. This branch also exists in Iran, India, in the Middle East, and along the ancient migration route from the Russian Plain to the Middle East, particularly in Armenia and Turkey. The R1a haplotypes which were excavated in the Andronovo archaeological sites east of the Ural Mountains, and which have been dated at between 3800 and 3400 ybp (Keyser et al., 2009), probably belong to the Z94-L657 subclade (Klyosov, 2013). It seems that only two subclades, Z94 and L657, can be con- sidered descendants of the Aryans in the traditional sense. These subclades match the history, archaeology, and languages of the steppe people. They rode chariots and, in the middle of the 2nd millennium BC, arrived in India (Indo-Aryans), Iran (Avesta Aryans), and Mesopotamia (Mitanni Aryans) (Klyosov & Rozhanskii, 2012b). R1b bearers, called the Arbins, comprise about 60% of the current population of western and central Europe. R1b appa- rently arose around 16,000 ybp (Klyosov, 2012b) in central Asia, perhaps in the Altai region. Its subclade, M73, is ob- served in Siberia and central Asia; subclade M269 is found in Bashkortostan near the South Urals; between 6200 and 5500 ybp, subclade L23 and its downstream subclade Z2105 can be found on the Russian Plain, in the Caucasus, and in Mesopota- mia; between 5500 and 5000 ybp subclades L51 and L11 are found on the migration route between the Middle East and the Pyrenees. R1b-U106 and P312 arose in Iberia around 4800 ybp Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 102  A. A. KLYOSOV, G. T. TOMEZZOLI and apparently became the initial population of the Bell Beaker culture of continental Europe. L21 apparently arose in the south of France about 4000 ybp and moved to England and Ireland sometime later. A common ancestor of nearly 25% of the cur- rent Irish population, who lived around 1500 ybp (Klyosov, 2012b), belonged to M222, a subclade downstream of L21. In addition to R1a bearers, since ~9000 ybp in Europe, and R1b bearers, since ~4800 ybp in Europe, ancient Europe was inhabited by bearers of other haplogroups, among them E1b, G2a, F, I1, I2, J2, K. Their migration routes and dates of arrival in Europe remain obscure. Haplogroups E1b and J2 apparently moved to Europe from North Africa or from the Middle East. Haplogroup G2a moved apparently from the Near Asia, proba- bly from the Iranian Plateau. Haplogroups I1 and I2 might have moved westward from the Russian Plain, as had haplogroups IJK (see Figure 1), between 45,000 and 40,000 ybp. The arrival of haplogroups F and K in Europe has not been dated. Recently, ancient bones in Spain dated as 7000 ybp (Lacan et al., 2011) have been shown to belong to E1b-V13. Strikingly enough, present day bearers of E1b-V13 haplotypes all coalesce to a common ancestor who lived only 3600 ybp. In other words, the contemporary V13 haplotypes reveal a gap between 7000 and 3600 ybp. The same gap pattern is observed in almost all the haplotypes of ancient Europe—except haplogroup R1b, which apparently played an important role not only in the set- tlement of, but also in the replacement of other haplogroups in Old Europe. It seems that the arrival of the Aryans (R1a) in Europe had been peaceful; there are no indications that it might have been genetically or otherwise violent. However, the arrival of the Arbins (R1b) was marked by almost complete elimination of the autochthonous haplogroups from Europe; E1b-V13 prac- tically disappeared, and started to proliferate only around 3600 ybp; G2a fled to the Asia Minor and to Mesopotamia and Cau- casus; R1a fled to the Russian Plain; I1 nearly disappeared and started to proliferate only around 3600 ybp; I2 fled to England, Ireland, and to the Russian Plain. I2 started to proliferate in Eastern Europe only around 2300 ybp. Only R1b itself has proliferated without pause from approximately 4200 ybp; a gap between 4800 and 4200 ybp is not filled with their common ancestors as yet. This brief historical outline of the settlement of Europe pro- vides the basis for our consideration of the movement of peo- ples and languages in Europe from about 9000 to the beginning of the Common Era (2000 ybp). How Haplogroups and Languages Are Connected DNA genealogy allows us to trace the migrations of ancient tribes and peoples, but, to date, it has not helped us to unambi- guously trace languages. Neither haplogroups nor languages stay the same in the course of migrations: haplogroups can disappear as a result of extermination, epidemics, and ecologi- cal catastrophes; in such cases the languages spoken by the haplogroup bearers typically disappear. On occasion, however, the languages are adopted by other tribes. In some cases the invaders adopt the language of the conquered people—when, for example, the women of a conquered people continue to teach their own language to their children, or when a conquered people has a more advanced civilization than its conquerors. Even if the haplogroup maintains itself during the course of long migrations, languages evolve following the rules of glot- tochronology and the natural dynamics of linguistic evolution. However, in some cases, a language can migrate and evolve along with the migration and evolution of haplogroups over long periods of time and over large distances. There are several conditions that must be met if our study of these cases is to be productive: 1) the connection between the haplogroups and languages has to be verified by linguistics, DNA, and archae- ology, 2) the languages must have evolved in time and distance, 3) the languages can be adopted by bearers of different hap- logroups in certain cases. We have said above that haplogroup R1a migrated across Anatolia to the Balkans between 10,000 and 8000 ybp; the group spread throughout Europe, moved east to the Russian Plain, and then went to India. The first date is supported by the fact that we find PIE in Anatolia between 10,000 and 9000 ybp (Gray & Atkinson, 2003; Bouckaert et al., 2012). PIE could have been formed and evolved during the long migration from the Altai Mountains to Anatolia. Then, the language migrated with the same R1a haplogroup to the Balkans and across Europe, where around 6000 ybp it split into branches; members of haplogroup R1a arrived around 4800 - 4600 ybp on the Rus- sian Plain as speakers of Indo-European language(s). DNA genealogy has confirmed that haplogroup R1a arrived in India as the legendary Aryans around 3500 ybp; even today nearly 72% of some Indian upper castes are R1a bearers (Sharma et al., 2009). Therefore, it seems that it was indeed haplogroup R1a carried PIE from about 20,000 to 10,000 ybp, and IE (or some kind of proto- or pre-IE languages from about 10,000 to 3500 ybp. The facts that 1) the peoples of the Russian Plain continue to speak IE languages, and 2) up to 63% of Russians today belong to haplogroup R1a, and 3) there are marked similarities between the Slavic languages and Sanskrit, permit us to conclude that the migration of bearers of haplogroup R1a were also bearers of Proto Indo European and Indo European languages. We can add to our earlier description of haplogroup R1b’s (the Arbin’s) migratory route the following points: around 6500 - 6000 ybp, on its way from the Russian Plain south over the Caucasus and probably—concurrently—along the eastern side of the Caspian Sea and Eastern Iran, it moved to the Middle East, the Tigris and Euphrates basin; between 6000 and 5000 ybp it apparently established the Sumerian civilization; between 4800 and 4500 ybp it moved to Europe following several routes. One route brought the Arbins through Northern Africa to the Pyrenees. Between 4800 and 4500 ybp, they arrived in conti- nental Europe as bearers of the Bell-Beaker culture; another route brought the Arbins to Europe through the Mediterranean islands and the Apennines; around 4500 ybp, yet another route brought the Arbins to Europe via the Pontic steppes. In the first part of their migration, along the northern Eura- sian route, the Arbins crossed territories, populated at least for the last two millennia (and very probably also much earlier), by speakers of Turkic languages, such as Chuvashes, Bashkirs, Tatars. We can conclude that the Arbins might have carried languages which were proto-Turkic, or Dene-Caucasian, or Sino-Tibetan. We tentatively call these languages Arbin, or R1b, or Non Indo European (NIE) agglutinative languages. In the Caucasus, the Arbins left the northern Caucasian group of lan- guages, together with a characteristic vigesimal counting sys- tem. Two thousand years later, the Arbins brought the same base-20 counting system to the Pyrenees. The R1b bearers Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 103  A. A. KLYOSOV, G. T. TOMEZZOLI brought their Arbin language(s) first to Mesopotamia, then to the Sumer state (Assyrians, the likely descendants of the Sumerians, today are largely R1b bearers, which is unusual for the Middle East [Klyosov, 2012b]), then to Iberia, where the present day Basques, 87% - 93% of whom belong to hap- logroup R1b, also employ the vigesimal counting system. As Bell Beaker tribes the Arbins moved north to continental Europe, and brought their agglutinative NIE languages, which apparently were spoken in Europe between 4500 and 3500 - 3000 ybp, and up into the Common Era (e.g., probably, Picts) and to the present (Basques). During the period of 3000 - 2300 ybp many R1a tribes mi- grated with their IE languages from the Russian Plain to central, western and southern Europe bringing to Europe the peoples later called Germans, Italics, Greeks, Illyrians, Balto-Slavs, and Celts (the Hallstatt and La Tene cultures flourished between 2600 and 2400 ybp). We posit that some Arbin peoples adopted the IE languages from the R1a bearers and, in exchange, intro- duced NIE loan words and grammatical structures. One group of Arbins were forebears of the Basques in the Pyrenees and the South of France, as well as the Picts in northern Scotland, and, possibly, the Etruscans in Tuscany. Linguistic Theories Regarding the Ancient European Settlements Let us move now to current linguistic theories about ancient European settlements, and compare their notions with those of DNA genealogy. The Vasconic and Afro-Asiatic Substratum Theory: The Linguistic View The Vasconic and Afro-asiatic substratum theory of Venne- mann (2003) proposes that several millennia after the end of the last Ice Age, when the glaciers receded (around 10,000 ybp), NIE peoples started to settle in southern Europe. These peoples were responsible for many European toponyms, hydronyms, and floral and faunal names, some of which have survived up to our times. Krahe (1954, 1964) believed that many of these toponyms and hydronyms were Indo European, but Vennemann was convinced that they contained NIE roots. Krahe argued that hydronyms from the Atlantic were imposed on the Baltic shore areas before 3500 ybp, and preceded the formation of the IE Baltic, Celtic, Germanic, Illyrian, Venetic and Italic language groups. Because of their similarities, Krahe concluded that the toponyms and hydronyms descended from a common language system he named Old European (OE). According to him, Old European constituted a language layer intermediate between PIE and the IE Baltic, Celtic, Germanic, Illyrian, Venetic and Italic language groups. Schmid (1987, 2001) extended Krahe’s OE concept by in- cluding the Eastern Slavic languages. Vasconic is what Ven- nemann called the language family of the NIE populations which imposed the toponyms and hydronyms. The Basque language would be the only surviving language of this family. Another argument in support of the Vasconic theory is the per- sistence in modern languages of traces of the base 20 counting system that would be a relic of the Vasconic culture. Vennemann (2003) also observed that on the Atlantic shore area of Europe there are toponyms that are neither Vasconic nor IE. He named the languages responsible of these toponyms Se- mitidic. According to Vennemann, these languages were related to the Mediterranean Hamito-Semitic languages, and were spo- ken along the Atlantic shore between 7000 and 3000 ybp. The Semitidic languages influenced IE superstratically (i.e., loaning terms for animals, advanced cattle breeding, buildings, warfare, and social organization—especially among the Germans of northern Europe) and substratically (i.e. contributing loan terms for plants, animals and herding, especially among the insular Celts). From about 7000 ybp onward, the Semitidic peoples— thought to be builders of megaliths—moved north along the Atlantic coast, reaching Great Britain and Ireland about 6000 ybp and Sweden about 5000 ybp. According to Baldi et al. (2006) there are several weak points in this theory: no megaliths have been dated before the Bronze Age (3500 - 2800 ybp); contrary to the traditionally accepted evidence that the Celts settled the Britain and Ireland no earlier than 4000 ybp, Vennemann’s theory requires a Celtic presence in England and Ireland about 7000 ybp; the building of mega- liths by Semitidic settlers is opposed by Renfrew and other ar- chaeologists; finally, Vennemann (2003) assumed that the Picts of northern Scotland were an Atlantic population or at least a population speaking an Atlantic language. A similar hypothesis, according to which the Picts were a NIE people, was set out by Zimmer (1898) on the basis of the Pictish customs of tattooing and their matrilineal social organization. Vennemann assumes no genetic connection between IE lan- guages and Vasconic and Semitidic languages. The expansion of the OE toward north Europe was restricted by the expansion of IE populations which adopted the Vasconic toponyms, hy- dronyms, and other lexical items related to the natural envi- ronment. The Basques, now living in a restricted region be- tween France and Spain, speak the only descendant language of OE or, according to Trask (1995, 1997), a patchwork of NIE languages is uncertain. Kuzmenko (2011) has reviewed the lexical borrowings made by the Indo-European languages of Europe from an “unknown substrate.” In his opinion, most linguists of the last century agree that an unknown substrate contributed not only to Ger- man languages but to all European IE languages. Kuzmenko finds merit in Vennemann’s hypothesis (2003) that the Basque language is the only surviving representative of the unknown European substrate. The Vasconic and Afro-Asiatic Substratum Theory: The View of DNA Genealogy The Vasconic and Afro-asiatic substratum (VAAS) theory is partially confirmed by DNA genealogy. DNA genealogy does not support the assumption of the VAAS theory that NIE populations began their European set- tlement in southern Europe after the end of the last Ice Age (about 10,000 ybp). Instead, it reveals that between 4800 and 4500 ybp (Klyosov, 2012b) the Arbins (R1b) moved into Europe using several routes (Northern Africa and the Pyrenees; the Mediterranean and the Apennines; the Pontic steppes). There were no speakers of Vasconic in Europe before 4800 ybp. However, the notion that Vasconic is a descendant of the an- cient Arbin language is in agreement with DNA genealogy data. Concerning the European toponyms, hydronyms, and the names of flora and fauna which have survived to the present, Venne- man’s hypothesis—that they are NIE—is acceptable, provided Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 104  A. A. KLYOSOV, G. T. TOMEZZOLI that his temporal estimate (10,000 ybp) be adjusted to 4800 ybp or later. DNA genealogy is in general agreement with the hy- pothesis of Krahe—that the languages are OE because, accord- ing to DNA genealogy, the Arbins (R1b) and their NIE lan- guages migrated as bearers of the Bell-Beaker culture (mainly R1b) and apparently dominated Europe between 4500 and 3000 ybp. Krahe (1954, 1964) appears to be correct in assuming that the Vasconic toponyms and hydronyms were imposed before 3500 ybp. According to DNA genealogy, the Vasconic language family is nothing other than an alternate name for the NIE languages of the Arbins (R1b). In other words, the NIE language of the contemporary Basques (R1b haplogroup) is probably a surviv- ing descendent language of the NIE languages of the ancient Arbins (R1b). A common ancestor of present day Basques, most of whom belong to haplogroup R1b, lived around 3700 ybp, which reflects a population bottleneck of the Arbins who arrived in Europe 4800 years ago (Klyosov, 2012b). The vigesimal counting system used both by the Basques and by the people of the Caucasus is supported by DNA genealogy data as a characteristic suggesting a connection between the ancient Arbins (R1b) (who migrated along the Northern route across the Caucasus, the Mediterranean islands, and northern Africa to Central Europe) and the isolated ancestors of the Basques in the Pyrenees region. Concerning the Semitidic, or Atlantic group of languages postulated by Vennemann (2003), they might indeed have sur- vived into the Common Era, and could have been spoken by the Picts of northern Scotland. The haplogroup of the Picts is un- known at present, but it might have been I1 or I2, because both haplogroups can be found in Britain today, and their common ancestor lived more than 15,000 ybp (Klyosov, 2010; see also Figure 1). The majority of the population of England and Ire- land carry the R1b haplogroup, which came to Britain and Ire- land after 4200 ybp. Indo European apparently belonged to the Aryan tribes (R1a); Non Indo European belonged to the Arbin tribes; Semitidic belonged to haplotypes I1, I2, and G2. The three linguistic communities had a common ancestor who lived around 55,000 ybp (Klyosov & Rozhanskii, 2012a). Therefore, Vennemann’s suggestion that there were no genetic connec- tions between IE languages, Vasconic languages, and Semi- tidic/Atlantic languages seems to be justified. The Anatolian Theory: The Linguistic View Renfrew (2001), in summarizing the Anatolian theory, af- firms that PIE, or the PIE family of languages, or the pre-PIE languages (Diakonov, 1984), were formed in central Anatolia during the Neolithic (about 9000 ybp), and that the PIE or IE languages were diffused throughout Europe from West Anato- lia along with the diffusion of the agriculture, which was Phase I of the PIE. According to Renfrew (2001), reliable radiocarbon datings indicate that the domestication of plants and animals from West Anatolia reached Greece and Crete around 8500 ybp. Linguistic changes in Greece and in the Danube and Balkan areas were due mainly to demic migrations during the 9th and 7th millennia ybp. It is possible that around 3500 ybp the diffusion of agri- culture east of what is now Ukraine could have brought speak- ers of Tocharian to the Chinese Sinkiang/Xinjiang. On the basis of their study of 87 languages and 2449 lexical items, Gray and Atkinson (2003) and Gray et al. (2011), sug- gest that an initial IE divergence occurred between 11,800 and 9800 ybp, allegedly in Anatolia. This is consistent with the separation of archaic PIE from pre-PIE; Ryder and Nicholls (2011) indicate a unimodal posterior distribution for PIE at about 10,400 ybp, which supports the Anatolian theory; other linguistic studies by Sturtevant (1962), Dolgopolsky (1987, 1993), Gamkrelidze and Ivanov (1984, 1995), Pringle (2012) and Bouckaert et al. (2012) also support the Anatolian theory. Interestingly, Bouckaert’s study is based on a model of spatial diffusion of infectious diseases. Renfrew (2001) affirms that a first linguistic advergence area was formed in the Balkan region between 7000 and 5000 ybp, which was Phase II of PIE. Some linguistic characteristics of the Celtic and Tocharian languages indicate that they were not part of the Balkan lin- guistic advergence area. The disaggregation of the Balkan ad- vergence linguistic area, which occurred at around 5000 ybp, indicates the end of Phase II of PIE, and the separation of proto-Greek from proto-Thracian, proto-Dacian, proto-Phrygian and others. At about the same time, there was a separation of the proto-Indo-Iranian spoken in the northern area of the Black Sea from its diffused form on the Iranian plateau and in India. Renfrew (2001) asserts that other IE languages were developed in advergence areas, where now their descendant languages are spoken. The Anatolian Theory: The View of DNA Genealogy The Anatolian theory is generally compatible with DNA ge- nealogy data, although the linguistic theory is silent about the evolution of PIE before 10,000 - 9000 ybp. As we discussed above, the proto-Aryans (R1a) migrated westward across Anatolia around 10,000 - 9000 ybp, which fits the linguistic estimates of Renfrew—9000 ybp (2001), Diako- nov—11,800 to 9800 ybp (1984), and Gray et al. (2003, 2011). Diffusion of agriculture, demic diffusion, and non-demic diffu- sion are concepts beyond the purview of DNA genealogy, though migrations of the proto-Aryans (R1a) from Anatolia to the Balkans about 9000 - 8000 ybp could represent Phase I of PIE. The later spreading of the Aryans (R1a) along with their IE languages across Europe about 8000 - 5000 ybp could rep- resent Phase II of PIE. The migrations eastward of Proto-Ary- ans to the Russian Plain and their split (about 4500 - 3500 ybp) into at least four migration routes to the south, southeast, east southeast, and east toward India could represent Phase III of PIE. The suggestion of the Anatolian hypothesis that Tocharian languages were not part of the Balkan linguistic advergence area is conditionally supported by DNA genealogy. According to Gray and Atkinson (2003), the Tocharian languages were an archaic branch, which arose around 7900 ybp, and were spoken by R1a populations in the Tarim basin. Based on the dating of the Tocharian language and the relatively high linguistic dis- tance of Tocharian A and B from the other IE languages (Tomezzoli & Kreutz, 2011), it is unlikely that the proto- Tocharians migrated westward to Europe and the Russian Plain with the proto-Aryans (R1a), and then moved back to the Tarim Basin. It is more likely that the proto-Tocharians migrated from the Altai region of north China to the nearby Tarim basin and remained there (never going to Europe), forming the autoch- thonous R1a peoples of Central Asia. The Anatolian hypothesis groups these Tocharians rather superficially with Europeans (Li et al., 2010), without any DNA justification—their haplotypes Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 105  A. A. KLYOSOV, G. T. TOMEZZOLI were not even reported for a comparison with European R1a haplotypes. It is not enough to consider Tocharians as Europe- ans on the basis of their somatic features and their clothing which, in 4000 ybp, looked like Scottish plaid. In fact, plaiding techniques could equally well have been brought to Europe by R1a tribes from the Altai and Central Asia. Still, there is some room for the Tocharian languages to be considered as derivatives of the archaic European R1a lan- guages of the IE family. Tocharian is possibly an ancient Cen- tum branch. In that case, we have to admit that Gray and At- kinson’s (2003) estimate of their appearance (7900 ybp) should be reduced at least to around 6000 ybp. There should also be a recognition of an earlier migration (between 6000 - 5500 ybp) of R1a bearers from Europe to the Altai region, and their possi- ble contributions to the Afanasyevo archaeological culture and perhaps to the Centum Tocharian languages in the area, includ- ing the Tarim basin. This concept is verifiable; if Afanasyevo bones not too far away from the Tarim basin are dated at least 5000 ybp and are shown to belong to the R1a-Z93 subclade, the case for a migration of R1a from Europe to the Tarim basin will be well supported. DNA genealogy data disallows Anatolia as the homeland of PIE and IE languages. DNA records show that these languages had no specific homelands—R1a bearers migrated over thou- sands of miles during the course of thousands of years. No ar- chaeological site can be possibly identified as a location in which IE split into branches—the branching of IE was a con- tinuous process of divergence and convergence over millennia. According to DNA genealogy data (see Figure 1), the prede- cessors of those who spoke PIE languages might have migrated 50,000 ybp or earlier from the unknown birthplace of the β-haplogroup. The birthplace might have been in Europe, the Russian Plain, or south Siberia (where they arrived between 40,000 - 35,000 ybp). Much later, sometime after 20,000 ybp, they migrated westward along with the R1a haplogroup via Ana- tolia, to the Balkans, to the Russian Plain and Pontic steppes, to the Middle East, Middle Asia, the Iranian plateau, the Ural mountains, Hindustan, South Siberia (again), North China, and Mongolia. All of these locations are migrational passing points and not homelands for the predecessors of the IE languages. The Kurgan Theory: The Linguistic View During the Mesolithic and the Neolithic, during the dry and cold period of the Younger Dryas (12,800 - 11,500 ybp), NIE and PIE peoples settled along the shores of the Black Sea. Ac- cording to the Kurgan theory, Proto Indo European formed in this area. At about 7600 ybp (Ryan et al., 1998), due probably to a cataclysm, the waters of the Mediterranean Sea entered the Black Sea through the Bosporus, triggering a rise in the water level and the submersion of many human settlements. The cata- clysm caused extensive migrations toward the Balkan region and Central Europe; it ultimately gave rise to the formation of the Neolithic cultures of Vinča and the Linearbandkeramic (LBK). Marija Gimbutas (1991) defined Ancient Europe as the European Culture developed between the 9th and the 7th millen- nia bp in the area of the Balkans, Greece, Adriatic region, Moldavia and Ukraine before the arrival of the IE bearers. Ear- lier (1956), she had provided a rather comprehensive descrip- tion of the cultural level of an ancient Europe characterized by well organized settlements, mixed orticular economies, high quality sculpture and ceramics, and elaborate religious tradi- tions. This materialized in the cultures of Bükk, Butmir, Cu- cuteni-Trypillia, Dimini, Karanovo, Lengyel, Petreşti, Vinča, and LBK. The languages spoken in Ancient Europe were NIE, as indi- cated by the survival of NIE agricultural, technological and social terms, toponyms, and personal and tribe names. Between 7500 and 6300 ybp Ancient Europe developed an advanced civilization, excelling in metallurgy. The Model of the Steppe, or the Kurgan model, or the Kurgan hypothesis, or the Kurgan theory was developed mainly by Gimbutas (1994, 1997), (see the synthesis by Marler [2001]); it proposes the presence, in about the 7th millennium bp, of territorial, nomadic, pastoral peoples speaking PIE languages. This Kurgan culture was situ- ated in the area of the Dnepr and Don basins, the middle and lower Volga basin, and in the Caucasus and Ural mountains. The tombs, covered by round tumuli named kurgans often con- tained weapons and other artifacts, suggest a culture that was patrilineal, pastoral (with rudimentary agriculture), territorial, and nomadic. The Kurgans had domesticated the horse around 7000 ybp (Bököny, 1997; Gimbutas, 1956). The Kurgan culture had characteristics different from those of the cultures of Ancient Europe, indicating to Gimbutas that it had not developed from the cultures of Ancient Europe. A first migration of Kurgan peoples, according to Gimbutas’ theory, took place about 6400 - 6300 ybp, as a result of the progressive drying of the steppes during the 8th and the 7th mil- lennium bp. The Kurgans moved towards Bulgaria, the Danube basin, and Central Europe. This migration is given support by the increasing number of kurgan tombs (discovered between the egalitarian tombs of the Ancient Europe cultures), the fortifica- tion of settlements, the damage to the settlements of the Varna, Karanovo-Gulmeniţa, Vinča, Lengyel and LBK cultures, and the replacement of some Ancient Europe cultures by new Kur- gan cultures. The development of IE languages was due to lan- guage substitution and bilinguism. A second migration took place around 5500 ybp from the area north of the Black Sea through Ukraine toward Poland, and central and east Germany. This migration led to the forma- tion of hybrid-cultures: the Baden complex in the middle Da- nube basin (which had the Vinča culture as substrate), the Ez- ero culture in Bulgaria (which had the Karanovo culture as substrate), the Globular Amphora culture in Romania, West Ukraine, Poland, and Germany (which had the Trichterbe- cherkultur [BK] as substrate). In parallel with the development of these hybrid-cultures, the fragmentation of PIE into several IE languages took place. A third migration, this one from the Volga steppes, took place between 5000 and 4800 ybp. It was more massive than the other two as witnessed by the numerous Yamnaya culture burials in the Balkan region and East Hungary. This migration caused the displacement of the hybrid cultures of central Europe toward northern Europe, southern Scandinavia, the Baltic area, and central Russia. This last migration was followed by a pe- riod of stability characterized by the formation of cultural groups (Gimbutas, 1994, 1997) which spoke distinct IE lan- guages. The Kurgan Theory: The View of DNA Genealogy DNA genealogy data suggests that the Kurgan theory is incompatible with the history of Europe. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 106  A. A. KLYOSOV, G. T. TOMEZZOLI According to the DNA data, PIE arrived in the Balkans after a long migration from central Asia. Using strontium isotopic measurements, Boric and Price (2013) have shown a significant increase in non-local individuals in the Balkans from ~8200 ybp. This generally coincides with the arrival in the Balkans of R1a peoples and IE languages. Neither the people nor the lan- guages came from the Pontic steppes. DNA genealogy indicates 1) a migration of R1a peoples eastward from Europe to the Russian Plain between 4800 and 4600 ybp (i.e. a direction opposite to that suggested by the Kurgan theory), and 2) a migration of R1b peoples from Asia to the Russian Plain and then southward between 7000 and 5000 ybp, and westward, between 5500 and 4500 ybp. In other words, the migrations of the Arbins (R1b) and the Aryans (R1a) were separated in time and went in largely opposite directions. Over- all, NIE speakers were moving west to Europe and south to the Caucasus; IE speakers were moving east. The Kurgan theory posits language migration in the opposite directions. In other words, the Kurgan theory distorts the whole pattern of what happened in Europe and the Russian Plain between 5000 and 3000 ybp. Additionally, contrary to what is proposed by the Kurgan theory: —PIE speakers and their languages were not settled or formed along the shores of the Black Sea between 12,800 and 11,500 ybp. At present, we don’t know which haplogroups were the most affected by the Black Sea cataclysm. The victims might have been G2a, E1b, F, I1, I2, etc., with survivors mov- ing westward, to Europe. —Ancient Europe cannot be considered as having an estab- lished European culture developed between the 9th - 7th millen- nia bp in the area of the Balkans, Greece, the Adriatic, Molda- via, or Ukraine before the arrival of IE. In fact, the IE speakers (R1a) arrived in the Balkans and further in Europe between the 10th - 8th millennia bp. —The languages spoken in Gimbutas’ Ancient Europe were not totally NIE. In fact, the arriving IE speakers (R1a) intro- duced their IE languages between the 10th - 8th millennia bp. The survival of NIE agricultural, technological and social terms, toponyms, and personal and tribe names cannot be considered an argument supporting a totally NIE Ancient Europe, since from the 10th millennium on IE and NIE languages co-existed in Europe —Gimbutas’ theory is in error when it proposes the forma- tion of territorial, nomadic, pastoral populations speaking PIE languages (collectively named the Kurgan culture), in the 7th millennium bp in the area of the Dnepr and Don basins, the middle and lower Volga basin, the Caucasus and the Ural mountains. In fact, there were no PIEs (R1a) at those times in those territories. The Kurgan theory apparently has inverted the roles of the NIE (R1b) and the IE (R1a). —The Kurgan theory is in error in ascribing kurgans, no- madism, and the domestication of horses to speakers of IE who lived around 7000 ybp. Instead, these cultural features should be ascribed to NIEs (R1b) who migrated westward. —Gibutas claims that IE speakers migrated to Europe three times--first, between 6400 and 6300 ybp; second, around 5500 ybp (from the area North of the Black Sea); third, between 5000 and 4800 ybp (allegedly from the Volga steppes). These claims are unsupportable. There were no IEs (R1a) in the Volga step- pes between 5000 and 4800 ybp or earlier; they arrived between 4600 and 4300 ybp. Had they been in the steppes, they would have been moving from Europe eastward. As we suggested above, there might have been an ancient migration route for R1a bearers (between 6000 - 5000 ybp). That route has not been proven as yet. If it is proven, it will most certainly be a migration to the east rather than the west as Gimbutas alleged. The Palaeolithic Continuity Theory: The Linguistic View Writing a half century after Gimbutas proposed the Kurgan theory, Alinei (2001) asserts that a great IE invasion in the Chalcolithic, triggering a total ethnic and linguistic substitution on a continental scale, is simply inconceivable. He suggests that the greater part of the common Neolithic IE lexicon, (i.e. loan words designating innovative devices like the plow, the yoke, the wheel, some domesticated animals, plants, and some met- als), was already diversified in almost all the IE languages dur- ing the Mesolithic and the Neolithic. With respect to the Anatolian hypothesis, Alinei (2001) ob- serves that limited migrations in the Balkans and Central Europe from Anatolia, even over a few millennia, are not suffi- cient explanation for the development and differentiation of IE languages in Europe. Moreover, these migrations cannot ex- plain the relatively large number of NIE toponyms in the Ae- gean area and the NIE words in Greek and other languages in southern Italy, Sicily, Sardinia, Corsica, and Spain. These ob- servations, according to Alinei, support the hypothesis that the populations coming from Anatolia were NIE speakers and that the Neolithic in Europe was a period of complex acculturation and geographical differentiation in which small migrating groups played a limited role with respect to the populations already inhabiting Europe. The fact that the greater portion of the grammatical structure of Celtic, Germanic, Italic, Greek, Illyrian, and Balto-Slavic is different from IE grammatical structures indicates that they could not have been formed in the Chalcolithic or Eneolithic. Alinei (2001) indicates that that the only possible solution to the linguistic conundrum is offered by the Palaeolithic Continu- ity Theory (PCT). PCT is supported by paleoanthropologists who have concluded that that not only Homo erectus but also Homo habilis and perhaps even Australopitecus were able to speak (Tobias, 1996). Some researchers in the cognitive sci- ences have reached the same conclusion, (i.e., to explain the innate character of human language it is necessary that Austra- lopithecus had some capacity for language [Pinker, 1994]). Thus, the structural portions of all human languages, including PIE (i.e. words, affixes, syntax) allegedly were formed a long time ago in Africa as part of human evolution. Alinei (2001) believes that Neolithic Europe would have been occupied by IE, NIE and Uralic peoples, though the NIE speakers would have influenced the IE languages only by con- tact and adstrates. Although he excludes the possibility of a massive invasion of Europe during the Chalcolithic or Neolithic, Alinei (2001) notes that an important hybridization took place in southern Europe at the beginning of the Neolithic as a result of the infiltration of NIE populations and the migrations of the Kurgan peoples during the Chalcolithic. Other hybridizations took place during the Bronze Age. However, these hybridiza- tions would have altered the languages and cultures of the IE populations only superstratically. Alinei (2001) asserts that Celtic and northCeltic peoples oc- cupied western Europe, including Brittany and Ireland, before the retreat of the glaciers, and that they created megalithism and the TBK cultures. During the Palaeolithic, the Italide or Italoide Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 107  A. A. KLYOSOV, G. T. TOMEZZOLI ethnolinguistic peoples occupied southern Europe from the Iberian Peninsula to Dalmatia. During the Neolithic, the Balkan area was influenced by NIE migrant groups of farmers, who created the Balkan Sprachbund, (i.e. the Balkan group of lan- guages: Greek, Serbian, Bulgarian, Macedonian, Albanese, and Romanian). According to Alineli (2001) the Kurgan culture introduced Turkic, not Iranian, influences to IE languages, and the border between the Trypillia and the Srednyj Strog cultures is the bor- der between Slavic and Turkic cultures. In this theory, the late Combat Axe population were the IE peoples influenced by the Kurgan culture. Furthermore, according to the Uniformity Prin- ciple of historical linguistics, the languages of Europe during the Bronze Age correspond to the languages of modern Europe (i.e., the areas of Bronze Age civilizations correspond to dia- lectal language areas, which in turn correspond to each IE lan- guage). The Palaeolithic Continuity Theory: The View of DNA Genealogy The Palaeolithic Continuity Theory appears incompatible with the history of Europe based on DNA genealogy data. The PCT places the origin of PIE languages in Europe in the Upper Palaeolithic (minimum 10,000 ybp), and links it to the arrival of people in Europe from Africa; it proposes the conti- nuity of peoples and languages in Europe for the last at least 10,000 ybp. This view is contradicted by DNA genealogy data. The only parts of the PCT which find support from DNA genealogy are: —PIE languages arrived in Europe around 10,000 ybp; they did not, however, arrive from Africa, but from Asia, via Anato- lia. —Words designating innovative devices, domesticated ani- mals, plants and some metals, were already diversified in IE languages, and were not brought by R1b “invaders” who ar- rived in Europe at the beginning of the 5th millennium bp. According to DNA genealogy data, genealogical lineages or haplogroups, and languages in Europe have not shown a con- tinuous pattern. In fact, according to DNA genealogy data: —IE (R1a) populations fled from Europe to the Russian Plain around 4600 ybp. There were at least ten R1a tribes each with a distinct subclade/SNP and/or branch of haplotypes, which migrated back to Europe after 3000 ybp. —Haplogroup G populations were almost completely elimi- nated in Europe between 4500 and 4000 ybp, apparently by the arrival of the Arbins (R1b); the survivors fled to Asia Minor, Mesopotamia and the Caucasus. There are excavated haplo- types of E-V13 dated 7000 ybp; however, the common ancestor of contemporary E-V13 bearers lived only 3500 ybp, indicating a population bottleneck . —Haplogroup I1 populations were almost completely elimi- nated in Europe between 4500 and 4000 ybp; they went through a severe population bottleneck until around 3600 ybp, which was a new beginning for I1 haplotypes in Europe. —Haplogroup I2 populations were almost completely exter- minated in Europe 4500 ybp, and the survivors fled to England and Ireland, and to eastern Europe. Present day I2 populations have common ancestors at 4800 ybp and 2300 ybp, respectively (Klyosov, 2012c). —NIE speakers (R1b) arrived in Europe near the Pyrenees around 4800 ybp; they arrived at the Apennines and the Bal- kans from the Pontic steppes, around 4500 ybp. These migra- tions caused major disruptions in the populations and languages of Old Europe. There are other aspects of PCT that are questionable in the light of DNA genealogy: —The notion that a few millennia in the Neolithic and a lim- ited number of migrations to the Balkans and central Europe from Anatolia were not sufficient for the development and dif- ferentiation of the IE languages in Europe is questionable. In fact, IE speakers (R1a) were in Europe from about 10,000 to about 4500 ybp. Thus, it cannot be assumed that there was a too short time for “development” and “differentiation” of IE lan- guages. —The proposal of the PCT that the arrival of IE languages from Anatolia cannot explain the relatively large number of NIE toponyms in the Aegean area and the NIE words in Greek and other languages of South Italy, Sicily, Sardinia, Corsica and Spain (see above; Alinei, 2001) is questionable. The IE speakers (R1a) did not come to an empty Europe, there already were NIE populations of haplogroups E, F, G, I1, I2, J2, K, etc. So, IE languages were very likely introduced in a NIE speaking Europe. Moreover, the PCT assumption that the populations coming from Anatolia were NIEs (see above) is contradicted by DNA genealogy data. It might well be, though, that some other haplogroups/tribes speaking NIE languages also migrated to Europe about between 10,000 and 9000 ybp; nevertheless, even if that had happened, it would not change the language land- scape of ancient Europe. —The PCT suggestion that the structural portions of all hu- man languages, formed long ago in Africa in connection with human evolution (see above) appears erroneous. Nobody can responsibly exclude the idea that H. habilis and Australopith- ecus were able to speak; however, DNA genealogy has shown that non-Africans do not have “African” SNPs on their Y chromosomes (Klyosov & Rozhanskii, 2012; Klyosov et al., 2012). Africans and non-Africans have plenty of SNP-muta- tions from a common ancestor of humans and chimpanzees; however, non-Africans have apparently, not received them from the Africans (ibid.). As a consequence of this lack of DNA data, it is hard to imagine that African languages could have evolved into PIE languages. Overall, it is highly ques- tionable that “anatomically modern homo” arose in Africa (Klyosov & Rozhankii, 2012; Klyosov et al., 2012; Bednarik, 2012, 2013), see also Figure 1. —The suggestion of the PCT that Celtic and north Celtic populations occupied Western Europe, including Brittany and Ireland, as long ago as before the retreat of glaciers appears erroneous. According to DNA genealogy data, Celtic IE lan- guages reached England and Ireland in the 3rd millennium bp. Their languages were imposed on the existing NIEs (R1b). This explains why Indo European languages are spoken today in Britain and Ireland by R1b populations (around 90% and above of today populations) plus a few (singular per cent) of R1a, I1, I2, and other minor haplogroups populations in Britain and Ireland. Earlier Genetic Studies This section describes a number of erroneous statements made in the early stages of genetic genealogy (also called genogeography and/or population genetics), in the 1990s and 2000s. Some of these statements still carry weight in linguistics. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 108  A. A. KLYOSOV, G. T. TOMEZZOLI The founding fathers of genetic genealogy claim, for example, that bearers of R1b lived in Europe 30,000 ybp (Wells et al., 2001; Wells, 2006), or between 40,000 and 35,000 ybp years ago (Semino et al., 2000). The main reason for this presumption is, apparently, that if R1b populations live in Europe now, they have lived there always. The claim that there were R1b tribes in Europe about 30,000 ybp, stuck for 15 years and even continues to be cited in contemporary population genetics literature. The date has been cross-cited hundreds of times in academic publi- cations. However, according to DNA genealogy, R1b tribes arrived to Europe only between 4800 and 4500 ybp (Klyosov, 2012b). The founding fathers of genetic genealogy claimed initially that haplogroup R1a arose in the southern Russian steppes about 15,000 ybp (Wells et al., 2001). Five years later, the es- timate date was changed (without explanation) to 10,000 ybp (Wells, 2006). In fact, both dates were invented. Without offer- ing any substantiation for the claim, the founders postulated that the oldest R1a bearers survived the Ice Age in a Ukrainian refuge (Semino et al., 2000). As a result, R1a was called the Ukrainian haplogroup (e.g., Wiik, 2008) for years—without any justification. Genetic genealogists claim, without any supporting facts (for a mini-review see Klyosov et al., 2012) that genetic data show that man left Africa some 70,000 ybp (or 50,000 or 60,000 ybp). They make no calculations based on Y chromosome markers. They base their “Out of Africa” theory on the comparative di- versity of African haplogroups. However, diversity as a crite- rion of age is valid only in closed systems. In open systems, such as Africa in this particular case, diversity is a consequence of the mixing of bearers of different Y chromosomes. Unfortu- nately, these erroneous dates have been used in academic lit- erature from the 1990s to the present time. More recent genome studies have shown that there is a wide gap between the African genome exemplified with indigenous hunter-gatherer peoples (Schustler et al., 2010; Lachance et al., 2012, and ref. therein; Klyosov et al., 2012), and the non-African genome, as, in fact, should follow from Figure 1 above. There are no indications that non-Africans descended from Africans. African SNPs are absent, for example, in Europeans (Klyosov & Rozhankii, 2012; Klyosov et al., 2012). Klyosov et al. (2012) have shown that the stream of SNP mutations from a common ancestor with chim- panzees goes to the α-haplogroup, from which the African lineage (haplogroup A) split around 160,000 ybp, and evolved in a separate Y-chromosomal lineage from the Europeoid line- age. Another archaic African lineage split even earlier, some 200,000 ybp or perhaps some 350,000 ybp (Mendez et al., 2013); bearers of this archaic lineage still live in Africa. In other words, the “Out of Africa” hypothesis has presented a dis- torted pattern not only of the origin of man but also of the de- velopment of human languages (Klyosov & Rozhanskii, 2012; Klyosov et al., 2012; Bednarik, 2012, 2013). The population geneticists of the 1990s-2000s, have tried, apparently, to match the historical convictions of those decades by bending their DNA-based theories. They uncritically con- sider gradients of frequency (or clines), which can always be found for whatever reason, including population bottlenecks, ignoring the existence of downstream subclades. In many stud- ies (Hammer, 2009; Underhill, 2009; Zhivotovsky, 2004) erro- neous mutation rates were employed (e.g., population rate con- stants or Zhivotovsky mutation rates—which increase the ac- tual number of years to common ancestors by 300% - 400%). As a result, the dating of populations are inflated by a factor of 3 or 4. Using these measures, Indo Europeans first appeared in India 14,000 ybp rather than 3500 ybp. There are dozens of examples of this kind in the literature. Similarly, Semino et al. (2000) concluded that some Euro- pean peoples (e.g., the Basques) are genetically different from others. But the majority of contemporary Basques belong to haplogroup R1b and share with about 60% of all Europeans the same arrival-in Europe-date. This conclusion was recently con- firmed using a genome-wide study of the Basques, according to which Basques are not genetic outlier among European popula- tions (Laayouni et al., 2010). In fact, southern Europe has many Palaeolithic haplogroups, such as E, F, G, K, J, which passed through a severe population bottleneck around 4500 ybp ap- parently as a result of the Arbins’ (R1b) arrival in Europe. Similarly, northern Europe has Palaeolithic haplogroups, such as I1, which passed the same bottleneck and started to recover only about 3600 ybp. We do not know their “genetic compo- nents” before that. Conclusion To sum up, early genetic studies of the origin of Europeans often present superficial conclusions based on scarce data that has not been subjected to serious scientific scrutiny. DNA ge- nealogy has not only enabled us to re-construct migration and settlement patterns in ancient Europe, it has also permitted us to put the leading linguistic theories under scrutiny. We have been able to disprove the Kurgan theory and the Palaeolithic Conti- nuity Theory and bring into question the “Out of Africa” hy- pothesis. We have also been able to fine tune the Vasconic and Anatolian theories. Acknowledgements The authors are indebted to Dr. Judith Remy Leder for her valuable help with the preparation of the manuscript. REFERENCES Alinei, M. (2001). An alternative model of the people-related sources in European languages: The “continuity theory”. In B. Mondadori (Ed.), The first roots of Europe (pp. 177-234). (in Italian) Anikovich, M. V., Sinitsyn, A. A., Hoffecker, J. F., Holliday, V. T., Popov, V. V., Lisitsyn, S. N., Forman, S. L. et al. (2007). Early upper paleolithic in Eastern Europe and implications for the dispersal of modernhumans. Science, 315, 223-226. doi:10.1126/science.1133376 Baldi, P., & Page, R. B. (2006). Review europa vasconica—Europa semitica. Lingua, 116, 2183-220. (in German) Bednarik, R. G. (2012). The origins of human modernity. Humanities, 1 , 1-53. Bednarik, R. G. (2013). Pleistocene palaeoart of Africa. Arts, 2, 6-34. Benazzi, S., Douka, L., Fornai, C., Bauer, C. C., Kullmer, O., Svoboda, J., Pap, I., et al. (2011). Early dispersal of modern humans in Europe and implications for Neanerthal behaviour. Nature , 479, 525-528. doi:10.1038/nature10617 Bököny, S. (1997). Horses and sheep in East Europe. In S. N. Skomal, & E. C. Polomé (Eds.), Proto-Indo-European: The archaeology of a linguistic problem. Studies in honour of Marija Gimbutas (pp. 136- 144). Washington DC: Institute for the Study of Man. Boric, D., & Price, T. D. (2013). Strontium isotopes document greater human mobility at the start of the Balkan Neolithic. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA, 110, 3298-3303. doi:10.1073/pnas.1211474110 Bouckaert, R. et al. (2012). Mapping the origins and expansion of the Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 109  A. A. KLYOSOV, G. T. TOMEZZOLI Indo-European language family. Science, 337, 957-960. doi:10.1126/science.1219669 Schustler, S. C., Miller, W., Ratan, A., Tomsho, L. P., Giardine, B., Kasson, L. R., Harris, R. S. et al. (2010). Completer Khoisan and Bantu genomes from southern Africa. Nature, 46 3, 943-947. doi:10.1038/nature08795 Diakonov, J. M. (1984). On the original home of the speakers of Indo European. Soviet Anthropolog y and Archaeology, 23, 5-87. doi:10.2753/AAE1061-195923025 Dolgopolsky, A. B. (1987). The Indo-European homeland problem. Mediterranean Archaeological Review, 3, 7-31. Dolgopolsky, A. B. (1993). More about the Indo-European homeland problem. Mediterranean Archaeological Review, 6-7, 251-272. Gamkrelidze, T. V., & Ivanov, V. V. (1984). Indo-European and the Indo-Europeans. Tbilisi: Tbilisi State University. Gamkrelidze, T. V., & Ivanov, V. V. (1995). Indo-Europeans and the Indo-Europeans.. In J. Nichols, & M. de Gruyter (Eds.), A recon- struction and historical analysis of a proto-language and a proto- culture (1128 pp). Berlin-New York. Gimbutas, M. (1991). The civilization of the goddess: The world of Old Europe, Harper. 544 pp. Gimbutas, M. (1956). The prehistory of Eastern Europe. Mesolithic, neolithic and copper age cultures in Russia and the Baltic area. American school of prehistoric researches. Harvard University Bul- letin, 20, Cambridge: Peabody Museum, Gimbutas, M. (1994). Das ende alteuropas (The end of the Old Euro pe ) (135 pp). Budapest: Verlag des Instituts fur Sprachwissensvhaft der Universitat Innsbruck. (in German) Gimbutas, M. (1997). The fall and transformation of Old Europe: Reca- pitulation. Journal of Indo-European Studies, 18, 351-372. Gray, R. D. & Atkinson, Q. D. (2003). Language-tree divergence times support the Anatolian theory of Indo-European origin. Nature, 426, 435-439. doi:10.1038/nature02029 Gray, R. D., Atkinson, Q. D., & Greenhill, S. J. (2011). Language evo- lution and human history: What a difference a date makes. Philoso- phical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 366, 1090-1100. doi:10.1098/rstb.2010.0378 Hammer, M. F., Behar, D. M., Karafet, T. M., Mendez, F. L., Hallmark, B., Erez, T., Zhivotovsky, L. A. et al. (2009). Extended Y chromo- some haplotypes resolve multiple and unique lineages of the Jewish priesthood. Human Genet ics, 126, 707-717. doi:10.1007/s00439-009-0727-5 Higham, T., Compton, T., Stringer, C., Jacobi, R., Shapiro, B., Trinkaus, E., Chandler, B. et al. (2011). The earliest evidence for anatomically modern humans in northwestern Europe. Nature, 479, 521-524. doi:10.1038/nature10484 Keyser, C., Bouakaze, C., Crubezy, E., Nikolaev, V. G., Montagnon, D., Reis, T., & Ludes, B. (2009). Ancient DNA provides new insights into the history of south Siberian Kurgan people. Human Genetics, 126, 395-410. doi:10.1007/s00439-009-0683-0 Klyosov, A. A. (2009). DNA genealogy, mutation rates, and some historical evidences written in Y-chromosome. II. Walking the map. Journal of Genetic Genealogy, 5, 217-256. Klyosov, A. A. (2010). Haplogroup I. Proceeding of Academy of DNA Genealogy, 3, 96-158. Klyosov, A. A. (2012a). Microsatellites and genes of Y-chromosome. Proceeding of Academy of DNA Genealogy, 5, 911-913. Klyosov, A. A. (2012b). Ancient history of the Arbins, bearers of hap- logroup R1b, from Central Asia to Europe, 16,000 to 1500 years be- fore present. Advances in Anthropology, 2, 87-105. doi:10.4236/aa.2012.22010 Klyosov, A. A. (2012c). Dinaric (East-European) and the “Isle” bran- ches of haplogroup I2a. Proceeding of Academy of DNA Genealogy, 5, 1304-1317. Klyosov, A. A., & Rozhanskii, I. L. (2012a). Re-examining the “Out of Africa” theory and the origin of Europeoids (Caucasoids) in light of DNA genealogy. Advances in Anthropology, 2, 80-86. doi:10.4236/aa.2012.22009 Klyosov, A. A., & Rozhanskii, I. L. (2012b). Haplogroup R1a as the proto Indo-Europeans and the legendary Aryans as witnessed by the DNA of their current descendants. Advances in Anthropology, 2, 1- 13. doi:10.4236/aa.2012.21001 Klyosov, A. A., Rozhanskii, I. L., & Ryanbchenko, L. E. (2012). Re- examining the Out-of-Africa theory and the origin of Europeoids (Caucasoids). Part 2. SNPs, haplogroups and haplotypes in the Y chromosome of Chimpanzee and Humans. Advances in Anthropol- ogy, 2, 198-213. doi:10.4236/aa.2012.24022 Klyosov, A. A. (2013). Subclade R1a-L342-L657 beyond Ancient Urals. Proceeding of Academy of DNA Genealogy, 6, 446-451. Krahe, H. (1954). Language and prehistory: European history accord- ing to the testimony of the language. Heidelberg: Quelle und Meyer. (in German) Krahe, H. (1964). Our oldest river nam es. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. Kuzmenko, Y. (2011). Earlier Germans and their neighbours: Linguis- tics, archaeology, genetics. St. Petersburg: Nestor-History. Laayouni, H., Calafell, F., & Bertranpetit, J. (2010). A genome-wide survey does not show the genetic distinctiveness of Basques. Human Genetics, 127, 455-458. doi:10.1007/s00439-010-0798-3 Lacan, M., Keyser, C., Ricaut, F.-X., Brucato, N., Tarrús, J., Bosch, A., Guilaine, J. et al. (2011). Ancient DNA suggests the leading role played by men in the Neolithic dissemination. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 108, 18255-18259. doi:10.1073/pnas.1113061108 Lachance, J., Vernot, B., Elbers, C. C., Ferwerda, B., Froment, A., Bodo, J.-M., Lema, G. et al. (2012). Evolutionary history and adapta- tion from high-coverage whole-genome sequences of diverse African hunter-gatherers. Cell, 150, 1-13. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2012.07.009 Li, C., Li, H., Cui, Y., Xie, C., Cai, D., Li, W., Mair, V. H. et al. (2010). Evidence that a west-east admixed population lived in the Tarim Basin as early as the early Bronze Age. BMC Biology, 8. doi:10.1186/1741-7007-8-15 Marler, J. (2001). L’Eredità di Marija Gimbutas: Una ricerca arche- omitologica sulle radici della civiltà europea. In B. Mondadori (Ed.), The first roots of Europe (pp. 3-22). (in Italian) Mendez, F. L., Krahn, T., Schrack, B., Krahn, A.-M., Veeramah, K. R., Woerner, A. E., Fomine, F. L. M. et al. (2013). An African American paternal lineage adds an extremely ancient root to the human Y chromosome phylogenetic tree. The American Journal of Human Genetics, 92, 454-459. Pinker, S. (1994). The language instinct: The new science of language and mind. London-New York: Penguin Books. Prat, S., Pean, S. C., Crepin, L., Drucker, D. G., Puaud, S. J., Valladas, H., Galetova-Laznickova, M. et al. (2011). The oldest anatomically modern humans from far southeast Europe: Direct dating, culture and behavior. PLoS ONE, 6, e20834. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0020834 Pringle, H. (2012). News & analysis: New method puts elusive Indo- European homeland in Anatolia. Science, 337, 902. doi:10.1126/science.337.6097.902 Renfrew, C. (2001). Origini indoeuropee: Verso una sintesi. In B. Mondadori (Ed.), The first roots of Europe. (in Italian) Rozhanskii, I. L., & Klyosov, A, A. (2012). Haplogroup R1a, its sub- clades and branches in Europe during the last 9000 years. Advances in Anthropology, 2, 139-156. doi:10.4236/aa.2012.23017 Ryan, W., & Pittman, W. (1998). Noah’s flood: The new scientific discoveries about the event that changed history. New York: Simon & Schuster. Ryder, R. J., & Nicholls, G. K. (2011). Missing data in a stochastic Dollo model for binary trait data and its application to the dating of Proto-Indo-European. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series C (Applied Statistics), 60, 71-92. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9876.2010.00743.x Schmid, W. P. (1987). “Indo-European”—“Old European”. In S. N. Skomal., & E. C. Polomé (Eds.), Proto-Indo-European: The archa- eology of a linguistic problem: Studies in honour of Ma ri j a G i mb u t as (pp. 322-338). Washington: Institute of the Study of Man. Schmid, W. P. (2001). Was Gewässernamen in Europa besagen. Aka- demie-Journal, 2, 42-45. Semino, O., Passarino, G., Oefner, P. J., Lin, A. A., Arbuzova, S., Beckman, L. E., De Benedictis, G. et al. (2000). The genetic legacy of Paleolithic Homo sapiens sapiens in extant Europeans: A Y chro- mosome perspective. Science, 290, 1155-1159. Sharma, S., Rai, E., Sharma, P., Jena, M., Singh, S., Darvishi, K., Bhat, Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 110  A. A. KLYOSOV, G. T. TOMEZZOLI Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 111 A. K. et al. (2009). The Indian origin of paternal haplogroup R1a1* substantiates the autochthonous origin of Brahmins and the caste system. Journal o f H u m a n Genetics, 54, 47-55. Sturtevant, F. H. (1962). The Indo-Hittite hypothesis. Language, 38, 376-382. doi:10.2307/410871 Tobias, P. V. (1996). The evolution of the brain, language and cogni- tion. In F. Facchini (Ed.), Colloquium VIII: Lithic-industries, lan- guage and social beh a v i o u r i n t h e f irst human form (pp. 87-94), Forli. Tomezzoli, G. T., & Kreutz, J. (2011). The linguistic position of the Tocharian. Proceedings of the 9th International Topical Conference: Origin of Europeans, Ljubljana, 67-86. Trask, R. L. (1995). Origin and relatives of the Basque language: Re- view of the evidence. In: J. L. Hualde et al. (Eds.), Toward a history of the Basque language (pp. 65-77). Amsterdam: Benjamin. Trask, R. L. (1996). The history of basque (480 pp). London, New York: Routledge. Underhill, P. A., Myres, N. M., Rootsi, S., Metspalu, M., Zhivotovsky, L. A., King, R. J. et al. (2009). Separating the post-glacial coancestry of European and Asian Y chromosomes within haplogroup R1a. European Journal of H um an Ge ne ti cs , 18, 479-484. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2009.194 Vennemann, T. (2003). Europa Vasconica-Europa semitica (999 pp). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. Wells, R. S., Yuldasheva, N., Ruzibakiev, R., Underhill, P. A., Evseeva, I., Blue-Smith, L., Jin, L. et al. (2001). The Eurasian heartland: A continental perspective on Y-chromosome diversity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United Stated of America, 98, 10244-10249. doi:10.1073/pnas.171305098 Wells, S. (2006). Deep ancestry: Inside the genographic project. Na- tional Geographic, 248, 247 pp. Wiik, K. (2008). Where did European men come from? Journal of Genetic Genealogy, 4, 35-85. Zhivotovsky, L. A., Underhill, P. A., Cinnoglu, C., Kayser, M., Morar, B., Kivisild, T., Scozzari, R. et al. (2004). The effective mutation rate at Y chromosome short tandem repeats, with application to human population-divergence time. The American Journal of Human Ge- netics, 74, 50-61. doi:10.1086/380911 Zimmer, H. (1898). Matriarchy among Picts. In G. Henderson, & G. Zimmer (Eds.), Leabhar nan gleann (The book of the glens) (pp. 1-42). Edinburgh: Norman Macleod

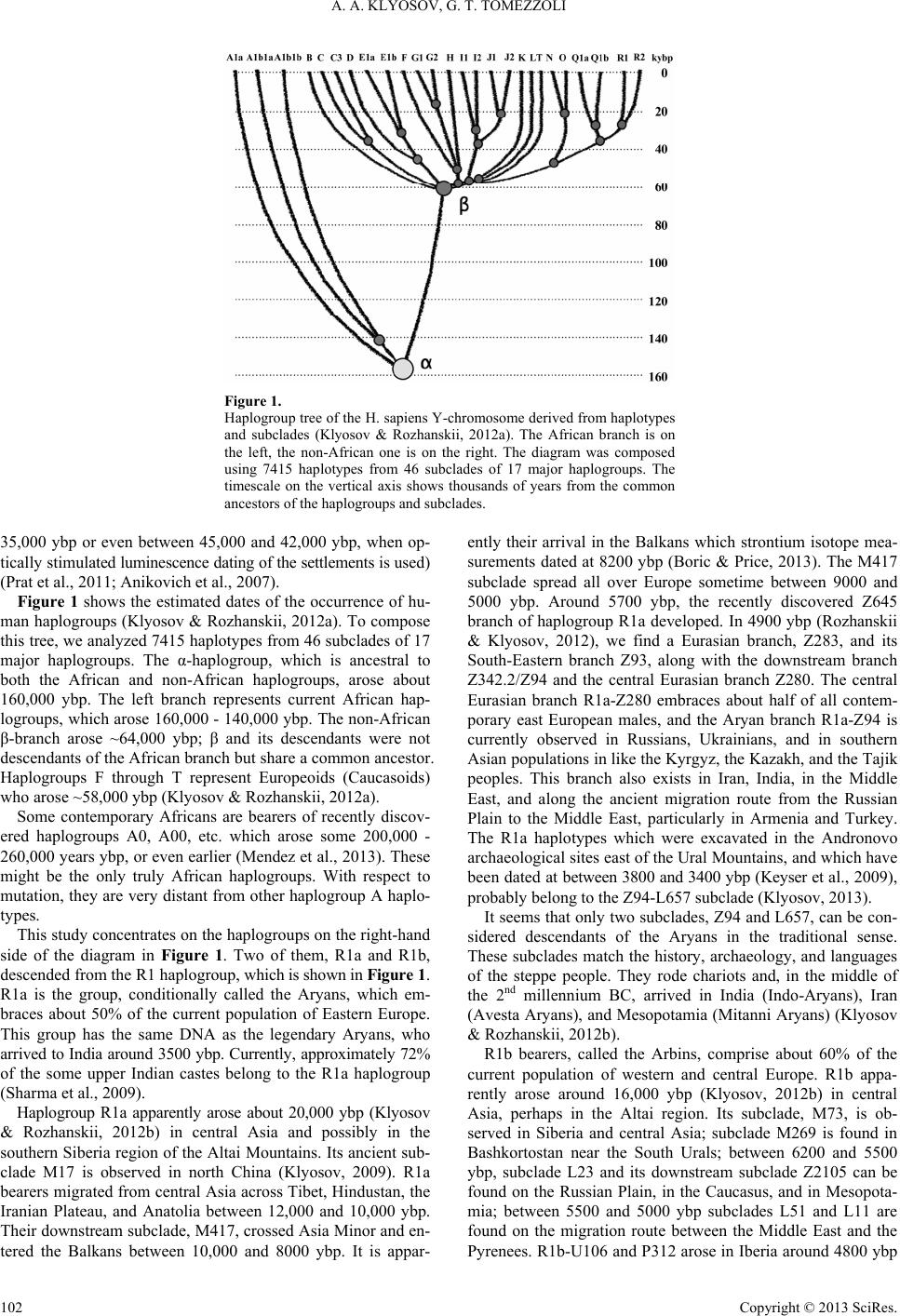

|