Creative Education 2013. Vol.4, No.4A, 19-28 Published Online April 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ce) DOI:10.4236/ce.2013.44A004 A Global Classroom for International Sustainability Education Arnim Wiek1, Michael J. Bernstein1, Manfred Laubichler2,3,4, Guido Caniglia2, Ben Minteer2, Daniel J. Lang5 1School of Sustainability, Arizona State University, Tempe, USA 2School of Life Sciences, Arizona State U niversity, Tempe, USA 3Santa Fe Institute, Santa Fe, USA 4Marine Biological Laboratory, Woods Hole, USA 5Institute of Ethics and Transdisciplinary Sustainability Research, Faculty Sustainability, Leuphana University of Lüneburg, Lüneburg, Germany Email: arnim.wiek@asu.edu Received February 11th, 20 1 3 ; revised March 15 th, 2013; accepted March 27th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Arnim Wiek et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons At- tribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Sustainability studies put emphasis on social-environmental-technical problems with local manifestations and global impacts. This makes especially poignant the need for educational experiences in which stu- dents confront the challenges of crossing cultural, national, and geographical boundaries in a globalized world and understand the historical, epistemological and ethical underpinnings of these diverse cultural conditions. The success criteria to evaluate the educational experiences demanded by the globalization of education, however, are yet to be specified and used in novel educational opportunities. A brief review of international sustainability education options currently available to students reveals a gap between the knowledge students may need to succeed in a globalized world and the opportunities available. Into this landscape, we introduce The Global Classroom, an international collaboration between Leuphana Univer- sity of Lüneburg in Germany and Arizona State University in the US. The project strives for an interdis- ciplinary and cross-cultural approach to equipping students with the knowledge, skills, and attitudes re- quired to take on sustainability challenges in international settings. We discuss the structure and organiza- tion of the Global Classroom model and share preliminary experiences. The article concludes with a re- flection on institutional structures conducive to providing students with the international learning oppor- tunities they may need to tackle sustainability problems in a globalized world. Keywords: Sustainability Education; International Education; Project- and Problem-Based Learning; Interdisciplinary Education Introduction Sustainability challenges, including climate change, loss of biodiversity, poverty, epidemics, and violent conflicts, manifest at specific locations; yet, the underlying causes are linked to other regions, nations, and even the global society. Hence, po- tential mitigation and solution options require coordinated and collaborative efforts around the world (Van der Leeuw et al., 2012). The coming generations of decision-makers, government agents, entrepreneurs, farmers, engineers, consultants, and oth- ers will have to face these challenges while collaborating across local, regional, national, geographical, and cultural boundaries. Collaboration of this extent requires the broad acquisition of specific competence, knowledge, skills, and attitudes, which in return has major implications for teaching and education (de Haan, 2006; Rowe, 2007; Sipos, 2008; Brundiers & Wiek, 2011). With these new teaching challenges, educators must deter- mine how to best equip students with these trans-boundary competencies. Classroom exercises that present sustainability problems and solution options are an important part of such a competency-focused approach. These classroom exercises, however, lack the cross-cultural and real-world experience that is critical for developing competencies that account for the local nuances of sustainability problems and solutions. There is a particular need for diverse and rich cross-cultural learning opportunities that simultaneously prepare students for under- standing sustainability challenges and build student capacity to develop robust solution options to these challenges. The success criteria or general learning objectives for such international educational experiences can be summarized as follows. Students need to be capable of working across national, geographical, and cultural boundaries, recognizing the cultural, historical, epistemological and ethical context of perceiving sustainability problems and developing solution options; and drawing on a pool of internationally-sourced solution ideas that can, when adapted, be transferred to different local contexts. Students ought to become: Sensitive to cultural differences and their historical origins (general cultural sensitivity). Attuned to how sustainability problems and potential solu- tions differ in diverse local contexts (context-specific prob- lem and solution orientation). Recognize, distill, adapt, and transfer sustainability knowl- edge, problem-solving frameworks, concepts, and best prac- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 19  A. WIEK ET AL. tices to local settings (problem-solving through adaptation and transfer). Integrate perceptions, knowledge, and skills across different disciplines and communities of practice in order to com- prehensively understand sustainability challenges and their ethical implications and to develop evidence-based solution options (interdisciplinarity). Capable of working in teams composed of individuals with diverse cultural backgrounds (cross-cultural teamwork). In the following, we briefly review international sustainabil- ity education options that are currently available to students and summarize the strengths and weaknesses of these education op- tions. Against this review background, we present the concept and structure of the Global Classroom, an international collabo- ration between Leuphana University of Lüneburg in Germany and Arizona State University in the US. The Global Class- room offers cross-cultural and interdisciplinary educational experiences with the intent to equip students with the knowl- edge, skills, and attitudes required to take on sustainability challenges in international settings. We conclude the article with a discussion of institutional structures best suited to pro- vide students with such international learning opportunities. The article offers a tangible example of how to provide in- ternational educational opportunities in line with the general criteria for advanced sustainability education. We hope the article provides a valuable source of inspiration for other uni- versities to initiate similar efforts or expand ongoing ones. International Opportunities for Sustainability Education Universities are in the process of recognizing the need for shifting and transforming established structures and practices in research, teaching, and operations in order to meet the sustain- ability challenges of the 21st century (Ferrer-Balas et al., 2008; Whitmer et al., 2010; Wiek et al., 2011b; Lang & Wiek, 2012). One important domain of this transformation is the emergence of international educational programs in sustainability. We first review the current state of international sustainability education opportunities through the lens of 17 international programs featured by the Association for the Advancement of Sustain- ability in Higher Education (AASHE). AASHE is a support network for educational organizations to advance sustainability in teaching, research, and operations. AASHE maintains a list of sustainability study abroad programs offered by various or- ganizations across the US1. We limit our review to academic institutions (as opposed to including other organizations) pro- viding undergraduates with sustainability study abroad oppor- tunities. While not comprehensive, the selected 17 programs present a robust spectrum of opportunities currently available to students in the US. We reviewed these programs based on the information available on the web (we did not request further information, conduct interviews, etc.). For the purpose of this review, we sought only information easily and readily accessi- ble to students landing on the program page. We use a review scheme based on the quality criteria for in- ternational sustainability education in a globalized world we explored above. For each program we asked the following questions. In how far does this program: Promote cross-cultural education? Address the context-specificity of sustainability problems and potential solutions? Offer capacity-building in complex problem-solving (solu- tion orientation)? Adopt an interdisciplinary approach to sustainability prob- lems and potential solutions? Teach teamwork in cross-cultural settings? To keep our review cursory, as intended, we reviewed if an element was either “strong,” predominantly “absent,” or “not clear” from available material. We formulated our answers based on keywords and phrases available on program landing pages. In particular, we focused on sentences beginning with phrases like, “The program is designed […]” or “this program’s goal […]” or “students will explore […]” For example, the phrase to provide “students with an opportunity to learn about contemporary and historical issues that impact development and social change in Southern Africa” is deemed a “strong” opportunity for cross-cultural education. The phrase, “This course will examine watershed management and its role in sustainable development,” represents a “strong” solution orien- tation; use of the word “transdisciplinary” indicated a “strong” interdisciplinary approach. The statement that students will, “cross borders, working collaboratively to solve problems” is deemed evidence of “strong” teamwork in cross-cultural set- tings (Table 1). The majority of international sustainability education oppor- tunities we reviewed lasted between one and two months (Ta- ble 2). Our review reveals that a majority of programs (14 of 17) provide students with a cross-cultural educational opportunity (Table 1). The majority of programs available address the con- text-specificity of sustainability problems and potential solu- tions (10 of 17); slightly fewer build capacity in complex prob- lem-solving (solution orientation) (8 of 17), or adopt an inter- disciplinary approach (8 of 17; 3 additional programs may, but this was “not clear” from available information). Our review reveals a dearth of programs offering students experience to work on cross-cultural teams (1 of 17). Only one program meets all of the presented criteria for international sustainability education opportunities (Table 3). The Global Classroom Experiment Into this landscape, we introduce The Global Classroom, an international collaboration between Leuphana University of Lüneburg in Germany and Arizona State University in the US. Background During the academic year 2009/2010, an international group of fellows in residence at the Institute for Advanced Studies in Berlin (Wissenschaftskolleg zu Berlin) formed a working group on curriculum reform. These fellows represented a wide range of disciplines (from physics and biology to political science and art history) and geographical regions (US, Europe, India, Israel). The group produced a manifesto and a set of recommendations (see: http://curriculumreform.org; Elkana et al., 2010). The central recommendation was to prepare students from the be- ginning of their studies to understand and deal with real-life problems at a global scale and to understand contextual (geo- graphical, cultural) dimensions of knowledge. 1Available at: http://www.aashe.org/about/aashe-mission-vision-goals Based on these discussions, the group began to explore the Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 20  A. WIEK ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 21 Table 1. International sustainability education oppo rtunities feature d by the Association for the Advancement of Sustainability in Higher Education (AASHE).  A. WIEK ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 22  A. WIEK ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 23 Table 2. Duration of the reviewed internatio nal programs. Program du ration 1 - 2 seme s t ers 1 - 2 months 1 - 3 weeks Number of programs 4 7 3 Table 3. Narrowing of the opportunity space for students in international sustainability education as more quality criteria are applied. Number of programs evaluated Number of programs promoting cross-cultural education Number of programs promoting cross-cultural education AND addressing context specificity Number of programs promoting cross-cultural education AND addressing context specificity AND having a solution o ri entation Number of programs promoting cross-cultural education AND addressing context specificity AND having a solution orientation AND adopting an interdisci plinary approach Number of programs promoting cross-cultural education AND addressing context specificity AND having a solution orientation AND adopting an interdisciplinary ap roach AND teaching cross-cultural teamwork 17 14 11 7 6 1 tive research model that is inquiry-based, problem-driven, con- text-sensitive and solution-oriented. By combining interdisci- plinary liberal arts approaches based on historical, epistemo- logical, ethical and sociological analyses with a problem- and solution-oriented sustainability science research educational model, the Global Classroom uses virtual technologies to edu- cate students on ways to engage and contextualize complex sustainability problems. The Global Classroom adopts method- ology and computational tools developed in other educational projects to facilitate teaching and learning. These include the Embryo Project (http://embryo.asu.edu), which developed workflows and manuals for peer review, writing and publishing based on modular research projects; system thinking ap- proaches to sustainability challenges; mapping methodologies inspired by urban sociology; walking methods developed in the fields of urban studies, photography, and sociology; and a Problem- and Project-Based Learning (PPBL) approach de- veloped in the School of Sustainability at ASU (Wiek et al., 2013). The Global Classroom is built on the understanding that when we deal with problems in isolation, without recognition of broader context and cause, we fail to generate effective, possibility of an educational pilot that would allow pursuing these recommendations. Of the institutions represented in this group, Arizona State University (ASU) and Leuphana Univer- sity of Lüneburg (LUL) provided the best opportunity to con- duct a pilot project. Both universities had recently begun a process of radical transformation that challenged traditional conceptions of research and education (Crow, 2010; Lang & Wiek, 2012), similar to other universities around the world (Ferrer-Balas et al., 2008); professional relationships (student exchange, co-teaching, joint supervision, etc.) already existed among faculty and students from both institutions; and both institutions were willing to facilitate and support a pilot in global education for continuation and expansion, beyond a one- off experiment. A new group emerged from these initial discussions that was tasked to develop the Global Classroom as an integrated joint program between ASU and LUL for 12 credit hours (US) or 30 credit points (Germany) that would run over 3 semesters and initially involve three overlapping cohorts of 40 students each (20 from each institution). With this idea, the group success- fully approached the Stiftung Mercator for funding. Through a series of virtual and in-person meetings involving faculty members, post-docs and teaching assistants from both institu- tions, we developed an integrated curriculum and a technology platform for start in January 2013. lasting solutions. Our educational institutions have a long re- cord of successfully training topical experts with narrowly con- strained skill sets. The Global Classroom draws off of these critical basic knowledge foundations. But where current educa- tional institutions seek only to better understand urban systems, the Global Classroom builds capacity for generating knowledge that sustainability change-makers—be they researchers, practi- tioners, or general citizens—can use to advance urban sustain- ability in addition to gaining a broader contextual understand- ing of these issues. Basic Features The initial Global Classroom focuses on one topic—Sus- tainable Cities—and approaches it from a variety of perspec- tives, including sustainability studies, sociology, social geog- raphy, history, history and philosophy of science and medicine, environmental ethics, and economics. The background of the first cohort of students is equally diverse. Applying the prince- ples of the curriculum reform manifesto as well as similar ef- forts in re-conceptualizing sustainability education (Wiek et al., 2011b), the Global Classroom is built on a hands-on, collabora- To equip students with the knowledge and tools they need to systematically engage urban sustainability challenges and drive toward positive change, the Global Classroom pairs an in- quiry-based mode of researching and experiencing the city with a sustainability competency approach to education. Further- more, the Global Classroom provides students with the skills to  A. WIEK ET AL. analyze the historical, epistemological and ethical foundations of these problems. A competency framework provides a “con- verging set of key competencies that can guide the design of programs and courses in sustainability, teaching and learning evaluations” (Wiek et al., 2011a). The key competency frame- work proposes five domains of knowledge and skill as critical to sustainability science research and education: systems think- ing, anticipatory thinking, normative thinking, strategic think- ing, and interpersonal skills (ibid.). Table 4 illustrates how learning outcomes of the Global Classroom map onto key competencies. The Global Classroom is designed and taught by an interna- tional team of faculty and graduate students, drawing on diverse disciplinary backgrounds from sustainability to biology to phi- losophy to environmental ethics, promoting an interdisciplinary approach. The Global Classroom engages in the first cohort 22 ASU undergraduate students and 20 LUL undergraduate stu- dents of diverse disciplinary backgrounds from art, psychology, biology, sustainability, and others. The students both in Germany and in the United States start with an open exploration of their cities. From the beginning, they work in international teams on collaborative projects that get refined over the course of the three semesters. The research projects include a focus on context-specific sustainability chal- lenges, using problem- and project-based learning approaches (Steinemann & Asce, 2003; Thomas, 2009; Yasin & Rahman, 2011; Wiek et al., 2013) but also emphasize the various con- textual factors needed to fully comprehend the issues. For ex- ample, in Phoenix, students have the opportunity to focus on water resource management, urban sprawl, or urban heat island; in Lüneburg, students have the opportunity to focus on sus- tainability-oriented business development, energy transitions, and urban-rural development tensions. In both cases, students will also investigate the larger cultural context and historical constraints for all these issues. Student research teams are ex- pected to investigate not just urban sustainability challenges, but also potential solutions, focusing on lessons to be learned from sustainability advancements in Phoenix, and Lüneburg, and around the world. Active exploration of the cities is complemented by discus- sion and instruction in background knowledge on cities, sus- tainability, history, ethics, etc. To this end, online-material is provided for discussion in the joint transatlantic sessions en- abled by the use of Vydio® technology. Other electronic teach- ing and communication platforms, such as social media and discussion forums, accompany in-class presentations and dis- cussions. Funding from Stiftung Mercator allows for two ex- change visits to the partner university by each cohort. During the first visit, students refine, defend, and plan their group re- search projects; during the second one they finish up and pre- sent their findings in an open event. Modular Design The Global Classroom curriculum on urban sustainability unfolds over three semesters spanning three core stages com- bining problem-based and solution-oriented sustainability ap- proaches with perspectives from history and philosophy of science as well as ethics (Figure 1). Each student’s resident cities, Phoenix and Lüneburg, frame case studies for urban challenges. Each of the six modules engage students through a suite of diverse content, context, and methodologies framed, augmented, and achieved through teamwork, stakeholder engagement, and Table 4. Linking learning outcomes of the global classroom to sustainability key competencies. Systems think i ng Anticipatory thinking Normative think i ng Strategic thinking Analyze complex feedbacks amon g cross-sector and cross-scale urban sustainabili ty challenges, l ike land-use change a nd energy c onsumption, as well as path dependencies that constrain directions o f development in society, as with transportation infrastructure. Create a n d craft plausible sustainability visions (desirable future states), for example a vision of healthy and livabl e urban communities. Evaluate implications of and trade-offs among different conceptions of the city, different motivations for devel op ment, and alternative visions of the future; assess how different w orldviews shape the reality of a city. Develop strategies t o s upport change in different societal contexts, for example a strategy for initiating and maintaining urban agriculture. Interpersonal skills Engage, motivate, collaborate with peers, decision-makers, stakeholders, and the public. Module 1 Teambuilding skills workshop Introduction to sustainability and cities Mapping and walking audits Stage 1 Basic Content Development Module 2 Introduction to sustainability research methodologies Mapping and walking audits Begin teamwork Module 3 Leuphana University students visit Arizona State University Teambuilding and project development Stage 2 Group Project Development Module 4 International group work continues Module 5 International group work continues Final presentations through virtual exhibition Module 6 Arizona State University students visit Leuphana University Final in-person presentations Stage 3 Synthesis Figure 1. Working model for t h e s t a g es a n d modules of the Global Classroom. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 24  A. WIEK ET AL. ational co ntent component of each module becomes the entry Study experience to bear on Methodology le, instructors cultivate an apprecia- The complexity and diversity of sustainability challenges a collaborative approach to problem and solution re- search. Students in the Global Classroom tackle sustainability llenges in international and interdisciplinary teams study s to de- e Global Classroom enriches the op- tions available in the landscape of international sustainability ed - liv eed to be capable of working across cultures, recognize cultural contexts, and draw upon a pool of at can, when adapted, be trans- fe cr intern llaborat io n. calls for Content The co point for student engagement with sustainability problems. By building systemic understanding of urban sustainability chal- lenges and pushing students to grapple with the potential out- comes of different societal trajectories and evaluate the impli- cations of these trajectories, the content component empowers students with a nuanced, holistic appreciation for the complex- ity of the urban environment. Students review the broad history of urban development; learn about current urbanization challenges related to popula- tion growth, social and demographic change, land-use land- cover change, water and energy systems, decision making, and infrastructure decay; encounter visions of sustainable cities and successful responses to urban challenges; and develop an un- derstanding of how change happens in cities. When synthesized and framed in a problem-based and solution oriented context, the knowledge developed in the content section provides a foundation for place-based, student-driven research on solution development. In addition, students will also further explore the historical origins and ethical challenges behind all these sus- tainability solutions. Context: The “Local” Case Just as an individual brings his/her own an issue and uses his/her experience as a medium of exchange in dialogue with his/her peers, the context component, here urban sustainability issues in Phoenix and in Lüneburg, will be the medium of engagement and exchange for Global Classroom students. By challenging students to apply their competency- based approach to conceive of specific urban sustainability problems in Phoenix and in Lüneburg, the context component equips students with place-based issues on which to engage their international peers. By collaborating across cities as dif- ferent as Phoenix and Lüneburg students cultivate an apprecia- tion for the diversity of urban sustainability challenges and solutions. Through engaging specific place-based challenges and learning about different problems shared or unique to dif- ferent cities and cultures around the world, students bring richer perspectives to problem conceptualization and solution-oriented research. Research Throughout each modu tion of exploring knowledge gaps. They discuss different types of knowledge generated by different types of research and how to apply different methods of knowledge generation when un- dertaking solution-oriented sustainability research. Furthermore, they will also convey to students how to critically evaluate, reflect and problematize these solutions and their constraints in light of historical, epistemological, and ethical considerations. Students obtain a broad methodological skill set to perform solution-oriented sustainability research. In addition to learning the importance of a dialectic approach to critical engagement, students are being introduced to problem analysis, sustainabil- ity visioning, and transition strategy development methods. Teamwork research cha to prepare them for this reality. By supplementing knowledge cultivation with professional skills development, including project management, team document organization, meeting facilitation, conflict resolution, and virtual collaboration, the Global Classroom provides students with an experience base on which to draw for future professional work and research. International Collaboration and Virtual Teamwork The majority of sustainability challenges have global causes and implications. The Global Classroom experience is designed to address problems of this scope by having students local problems and then engage with international peer velop a richer understanding of how global problems manifest differently (and similarly) in other local contexts. The Global Classroom allows students to explore not just different cities, but also cultures. Students develop an appreciation for diverse values and perceptions influence sustainability challenges and solutions. By providing coaching support and virtual platforms for international communication, the Global Classroom builds student capacity for cross-cultural collaboration, a critical in- gredient for interacting successfully in a globally intercon- nected world. The Global Classroom project pursues the goals of international education as a hybrid course that takes advan- tage of new media, technology, and learning theory. In addition, students gain first-hand experience with cutting-edge tools in video communication, online course environments, and online project presentation. Collaborative virtual group workspaces for participants and an online course environment that houses sup- porting course resources complete the Global Classroom learn- ing environment. Initial Experience with the Global Classroom In light of our review of international sustainability education opportunities, we find th ucation. Below, we discuss the ability of this model to de er on quality criteria for international sustainability education; we present our plan for formative and summative assessments of student performance and program learning objectives; and we delve into the challenges (expected and experienced) of implementing the program, as well as strategies for coping with experienced challenges. Continuous Assessment To succeed in addressing sustainability challenges in a glob- alized world, students n internationally-applied ideas th rred to different local contexts. The Global Classroom project provides various opportunities to acquire these capabilities through international education. Global Classroom students work in international team on di- verse place-based sustainability challenges in Phoenix and Lüneburg. As they shape their research, students are constantly challenged to combine the perspectives of international team members. In this way, students gain first-hand experience with oss-cultural teamwork and the different norms, perspectives, Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 25  A. WIEK ET AL. and approaches of their peers. Additionally, students and in- structors draw on diverse epistemological backgrounds to craft research questions—teams composed of students from the arts, psychology, biology, sustainability and other programs are being coached by instructors to tackle urban sustainability is- sues that do not recognize disciplinary boundaries. Student teams not only delve into sustainability problems, but are also encouraged to research potential solutions—drawing from German, US, and international expertise across disciplines. This includes recognizing, distilling, transferring, and adapting sus- tainability knowledge, problem-solving frameworks, concepts, and best practices to local settings. For continuous improvement, we are instituting a range of formative assessments to help us evaluate student learning and course effectiveness. One of our approaches to evaluating ef- fectiveness is through the sustainability key competencies framework (Wiek et al., 2011a). Adopting the competencies fr for on e vision of the Global Classroom runs up against university logistics, virtual collaboration, and ot rsity Logistics In conducting a three semester long collaboration, as op- s exhibited in many of th -month, and semester-to semester issues of te g criterity education opportunities. Promote cross-cultural context-specificity of Have a solution Adopt an interdisciplinary approach to sustainabili ty Teach teamwork in ttings amework allows for a comprehensive set of proxies for many of the quality criteria of international sustainability education outlined above (Table 5). For example, practice in cross-cul- tural teamwork develops interpersonal skills; synthesizing in- terdisciplinary perspectives to tackle an urban sustainability problem builds capacity in systems think about complex webs of influence among, say, infrastructure and political power. We are evaluating the development of student competencies though pre-, interim-, and post-assessments that will be coded, with standards of inter-rater reliability, at the conclusion of the first cohort. In addition, we conduct periodic student-student, student-instructor, and instructor-instructor reviews to allow going formative assessment of the structural aspects of the Global Classroom itself (e.g., effectiveness of virtual platforms, relevance of content, availability of instructor support, sources of conflict, course strengths and areas of improvement, etc.). Challenges Table 5. Exemplary use of sustainability key competencies as indicators for meetin Address the At times, th the reality of her challenges. Below, we explore a few of these challenges we have encountere d and coping strategies we have adopted as the program develops. Time Zones and Unive posed to shorter international courses a e international sust ainability education options, two logistical challenges arise. The first challenge occurs at the micro-level: the day-to-day issues of communicating with partners across an 8-hour time difference. Time zones present a two-fold challenge related to when classes can be held (either far earlier than nor- mal for one institution or far later for another), and when fac- ulty can find time to collaborate and plan for classroom and program activities. E-mail, video conferencing services, and the cloud-based software packages each present important tools for the Global Classroom to span the international dateline and communicate synchronously and asynchronously. As we dis- cuss later, however, such technological solutions come with their own issues. The second challenge occurs at the macro-level: the week- to-week, month-to aching a course simultaneously at two universities with sig- nificantly different semester calendars. Semester start- and end-dates, and holiday schedules perforate Global Classroom calendars. But these challenges also offer opportunities as they enable us to take advantage of non-overlapping semesters to organize exchange visits to Phoenix and Lüneburg, respec- tively. a of international sustainabili education sustainability problems and potential solutions orientation problems a nd potential solutions cross-cultural se S thi ystems nking ts fferent physical landscapes. al tions. Differences in urban decision-making contex leading to di Recognition of how loc factors contribute to diversity urban sustain abi li ty challenges and solu Incorporation of div erse knowledge domains to urban sustainability research questions. Anticipator thinking y ms or s research questions. onsideration of diverse rspectives to avoid conflict. xts over others. onsideration of winners rs when researching potential sustainabi lity solutions. . of ustainability solutions. y to solutions. cal Leverage disciplinary or test sustai n ability solutions. individual development. Interpersonal skills Navigatio n o f local contexts and multi-cultural team dynamics. Navigatio n o f local contexts and multi-cultural team dynamics. Navigatio n o f local contexts and multi-cultural team dynamics. Ability to bridge disciplines in team setti ng s and in public com munication . Navigatio n o f local contexts, cult ural, and disciplinary perspe ctives. Considera ti on of diverse perspectives to avoid conflict. Consideration of con t ext when analyzi ng ur ban proble solutions. Considera ti on of how different disciplinary approaches may or may not fully addres C pe Normative thinking Considera ti on of diverse perspectives to avoid conflict. Not privileging certain cultural conte C and loseNot privileging certain wa ys of knowing over others Considera ti on of diverse perspectives to avoid conflict. Strategic thinking Leverage cultural diversity to research and test suite potential s Leverage cultural diversit research and test suite of potential sustainability Appropriate, translate, and adapt knowledge of lo contexts in problem-solv ing efforts. diversity to more fully address research questions Cultivate dyna mic that draws on teammate strengths and supports team and Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 26  A. WIEK ET AL. Virtual Collabo co dail ens hats several transatlantic visits that were necessary to plan and con- solidate the s orga standinome up we and acceptabl olutions, sometimes last minute. Therefore, we are still seek- tional strategies for successful virtual C roaches we take to planning Global Classroom activities. Tensions are often palpable between those with more proc- “crea- al Classroom Ex- periment was presentedm inspiration, design, approach, and ability to mpiled criteria. Finally, w sustainability education will require more substantial change at ch- and eoselyl- lenges of potentpatible semetion sche- ll alty, se es. In as tol resources for sufficient virtual collaboration and technological ration llaboration is not a full s espite our best efforts. In of hours of video c Virtual teractions, and doz ubstitute for in-person in- deed, hundreds of e-m could not compensate for s the level of acad sarily affect adm yet interconnect Administratio yllabus and course ges require a lot of good g in order to c nization. In general, plan will, trust, flexibility, an ith feasibl - d e dules, as we post-docs, and re challeng ning challen under s ing and exploring addi collaboration. Beyond these more intangible issues of virtual collaboration are the invariable rules of using technologies in the classroom. If you need to use it, and your entire meeting revolves around the need of a technology to work correctly, it will fail some- times (we have empirical evidence). Institutional technology support (technician), patient students, and good-humored in- structors are instrumental in surmounting such technical hic- cups. ross-Disciplinary and Cross-Cultural Collaboration The Global Classroom seeks to equip students with tools and experiences on working in interdisciplinary, cross-cultural teams. The same applies to the instructors. We often experience first-hand the need for patience, broad perspectives, and flexi- bility when it comes to attempting to globalize the educational landscape. Different epistemological perspectives manifest in the app ess-driven, meticulous approaches vs. those with a more tive” attitude, for instance, when developing proposals, work plans, and course material. These tensions, when not addressed, can lead to frustration and reluctance to fully engage in con- tinuous deliberation and collaboration. If not addressed early, this could lead to resentment capable of undermining the entire Global Classroom effort. In response, we are learning to prac- tice the very process checks we teach to our students about successful international collaboration; listen to colleague- perspectives, respect the work being done, question assump- tions about differences in approaches, and communicate ques- tions appropriately, and institute regular assessment of team interactions. So far we have been successful. Conclusion This article started out with quality criteria for international educational experiences to prepare students for confronting sustainability challenges crossing cultural, national, and geo- graphical boundaries. With these criteria in hand, we reviewed student opportunities in international sustainability education. Our rough appraisal found that only one of seventeen programs reviewed fulfill all of the criteria. The Glob with its progra deliver on the co e reviewed the challenges of designing a program that we find fulfills the quality criteria of international sustainability educa- tional experiences. The Global Classroom is but one program between two in- stitutions supported by a generous external grant. While we find our model of international collaboration valuable, its scope is limited. True transformation of the landscape of international support, as well as intermittent travel funding, is essential. With institutional support, we can imagine generic global classroom teams securing outside funding of site visits, but only with the demonstrated institutional support for other facets of the class- room experience as we have experienced from Arizona State an emic institutions. Su inistration, faculty, d ways. n needs to work cl ially incom changes would neces students in different, to navigate the cha ster and vaca s establishing incentive search and teaching as ddition, finding way structures for facu sistants to tackle the leverage institutiona d Leuphana universities. Faculty need to develop skills in international collaboration and project management. In addition, faculty with valuable disciplinary perspectives but relatively untrained in working on interdisciplinary teams needs to learn to navigate the tension of such worldview-challenging experiences. Although at first dif- ficult, we expect the benefits of such work to far exceed the costs, opening up new streams for fruitful research, travel, and educational opportunities for faculty and students alike. Students need to develop exceptional flexibility as Global- Classroom-like programs come online. At a most basic level, the majority of the students may never have experienced chal- lenges to their worldviews. In addition, those participating in the class must be prepared to manage heavy workloads that may fall at odd-times in their conventional semester as accom- modations are made to pair university schedules. Students also need to be flexible regarding out-of-class working hours, as in- ternational peers may not be easily reached during conventional work times (e.g., the evening hours for one set of students may be the class hours for another). Where international travel is involved, faculty and administration need to coach students on how to secure outside funding (to ensure that all who are inter- ested have access to these international experiences), as well as on proper travel etiquette. All parties involved need to adopt to and integrate the prom- ising practices of virtual educational technologies. From in- class video conferencing to out-of class times, emails, and workflows, all parties will likely need to cultivate patience and skill in navigating the online world. These forays into virtual spaces, however, allows universities to tap into the growing body of resources available to online education efforts. A fully global classroom can take advantage of “flipped classroom” models (Strayer, 2007) in which students are free to interact with lesson content outside of the class and instructors are free to use class time to engage students on the nuances of cross- cultural perspectives, collaboration and knowledge translational and adaptation. In addition, such a “flipped” model would also secure valuable and scarce time in which students know they will be able to work together on joint projects, using the para- digm of problem- and project-based learning (Steinemann & Asce, 2003; Wiek et al., 2013). A critical step to internationalizing sustainability education is to establish the standards vital to ensuring quality student ex- periences. The Global Classroom can serve as a real-world laboratory for consolidating such standards and practices. Ad- ditional “meta research” along a clearly structured research design is required to evaluate, generalize, and transfer the in- sights gained. While more detailed studies need to be done, our Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 27  A. WIEK ET AL. review demonstrates the distance to go in closing the gap be- tween the knowledge, skills, and perspectives students need to, and the opportunities they have to hone these skills in interna- tional sustainability education. Future global classrooms will also need to press the envelope of cross-cultural fluency. Our Germany-US collaboration looks much different than, say, a US-China or Germany -South Africa collaboration might. Should our institutions choose advance the ideas embodied by the Global Classroom model, multiple and diverse partnerships will be required to encourage broad-based cultural exchanges. The suite of institutions providing student opportunities in interna- tional sustainability education, universities, like Arizona State University, Leuphana University of Lüneburg, and those re- viewed in this article, will play a critical role in providing stu- dents with the international learning opportunities they need to tackle sustainability problems in a globalized world. Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank their colleagues at Arizona State University and Leuphana University of Lüneburg, in- cluding Beatrice John, Sacha Kagan, Jane Maienschein, Rich- ard Creath, Sean Cohmer, Andrew Ells, Irma Sandercock, Charles Kazilek, Nils Ole Oermann, Robert Page and Sascha Spoun and our first cohort of Global Classroom students for their collaborative engagement and support in the first Global Classroom. The authors acknowledge financial support from the Stiftung Mercator. REFERENCES Brundiers, K., & Wiek, A. (2011). Educating students in real-world sustainability research: Vision and implementation. Innovative High- er Education, 36, 107-124. doi:10.1007/s10755-010-9161-9 Brundiers, K., & Wiek, A. (2013). Do we teach what we preach? An international comparison of problem- and project-based learning courses in sustainability. Sustainability, 5, 1725-1746. Crow, M. M. (2010).ch to address the grand challenges ioScience, 60, 488- 489. doi:10.1525/b Organizing teaching and resear of sustainable development. B io.2010.60.7.2 De Haan, G. (2006). The BLK “21” programme in Germany: A “Ges- taltungskompetenz”-based model for education for sustainable de- velopment. Environm e n t a l Education Resources , 1, 19-32. doi:10.1080/13504620500526362 Elkana, Y., Laubichler, M. D., & Wilkins, A. S. (2010). Call to reshape university curric u la . Nature, 467, 788. doi:10.1038/467788c Ferrer-Balas, D., Adachi, J., Banas, S., Davidson, C. I., Hoshikoshi, A., Mishra, A., Motododa, Y., Onga, M., & Ostwald, M. (2008). An in- :10.1108/14676370810885907 ternational comparative analysis of sustainability transformation across seven universities. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 9, 295-316. doi develop- can. Lang, D. J., & Wiek, A. (2012). The role of universities in fostering urban and regional sustainability. In H. A. Mieg, & K. Töpfer (Eds.), Institutional and social innovation for sustainable urban ment (pp. 393-411). London: Earths Rowe, D. (2007). Education for a sustainable future. Science, 317, 323- 324. doi:10.1126/science.1143552 Sipos, Y., Battisti, B., & Grimm, K. (2008). Achieving transformative sustainability learning: Engaging head, hands and heart. Interna- tional Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 9, 68-86. doi:10.1108/14676370810842193 teinemann, A., & Asce, M. (2003). Implementing sustainable devSel- opment through problem-based learning: Pedagogy and practice. Journal of Professional Issues in Engineering Education and Prac- tice, 129, 216-224. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)1052-3928(2003)129:4(216) trayer, J. F. (2007). The effect of the claSssroom flip on the learning t used an intelligent tutoring sys- Trnal 5-264. environment: A comparison of learning activity in a traditional classroom and a flip classroom tha tem. Ph.D. Thesis, Columbus, OH: Ohio State University. homas, I. (2009). Critical thinking, transformative learning, sustain- able education, and problem-based learning in universities. Jou of Transformative Education, 7, 24 doi:10.1177/1541344610385753 an der Leeuw, S., Wiek, A., Harlow, J., & Buizer, J. (2012). How much time do we have? Urgency and rhetoric in sustainability sci- ence. Sustainability Science, 7, 115-120. V doi:10.1007/s11625-011-0153-1 hitmer, A., Ogden, L., Lawton, J., Sturner, P., Groffman, P. M., Schneider, L., Hart, D. et al. (2010). The engaged university: Pro- viding a platform for research that transforms society. Fr W ontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 8, 314-321. doi:10.1890/090241 iek, A., Withycombe, L., & Redman, C. L. (2011a). Key competen- cies in sustainability—A reference framewo development. Sustainability Scien Wrk for academic program ce, 6, 203-218. doi:10.1007/s11625-011-0132-6 iek, A., Withycombe, L., Redman, C. L., & Banas Mills, S. (2011b). Moving forward on competence in sustain lem solving. Environment: Scien Wability research and prob- ce and Policy for Sustainable De- velopment, 53, 3- 12. doi:10.1080/00139157.2011.554496 iek, A., Xiong, A., Brundiers, K., & van der Leeuw, S. (2013). Inte- grating problem- and project-based learning into sustainability pro- grams—A case study on the School of Sustainability at Arizona W State Yted project based education for sustainable develop- University. Intern ational Journal of Sustainability in Higher Educa- tion, under Review. asin, R. M., & Rahman, S. (2011). Problem orien learning (POPBL) in promoting ment. Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences, 15, 289-293. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.03.088 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 28

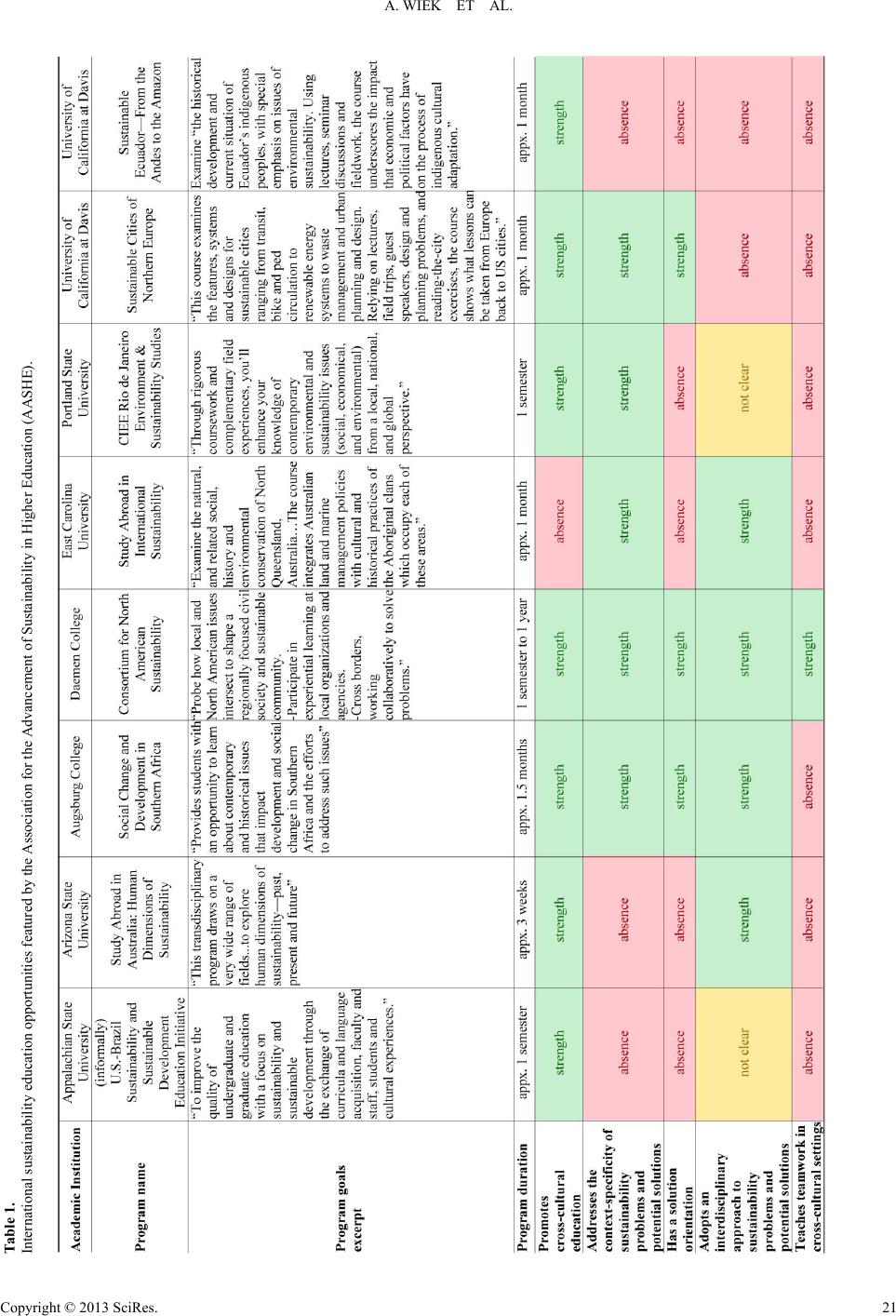

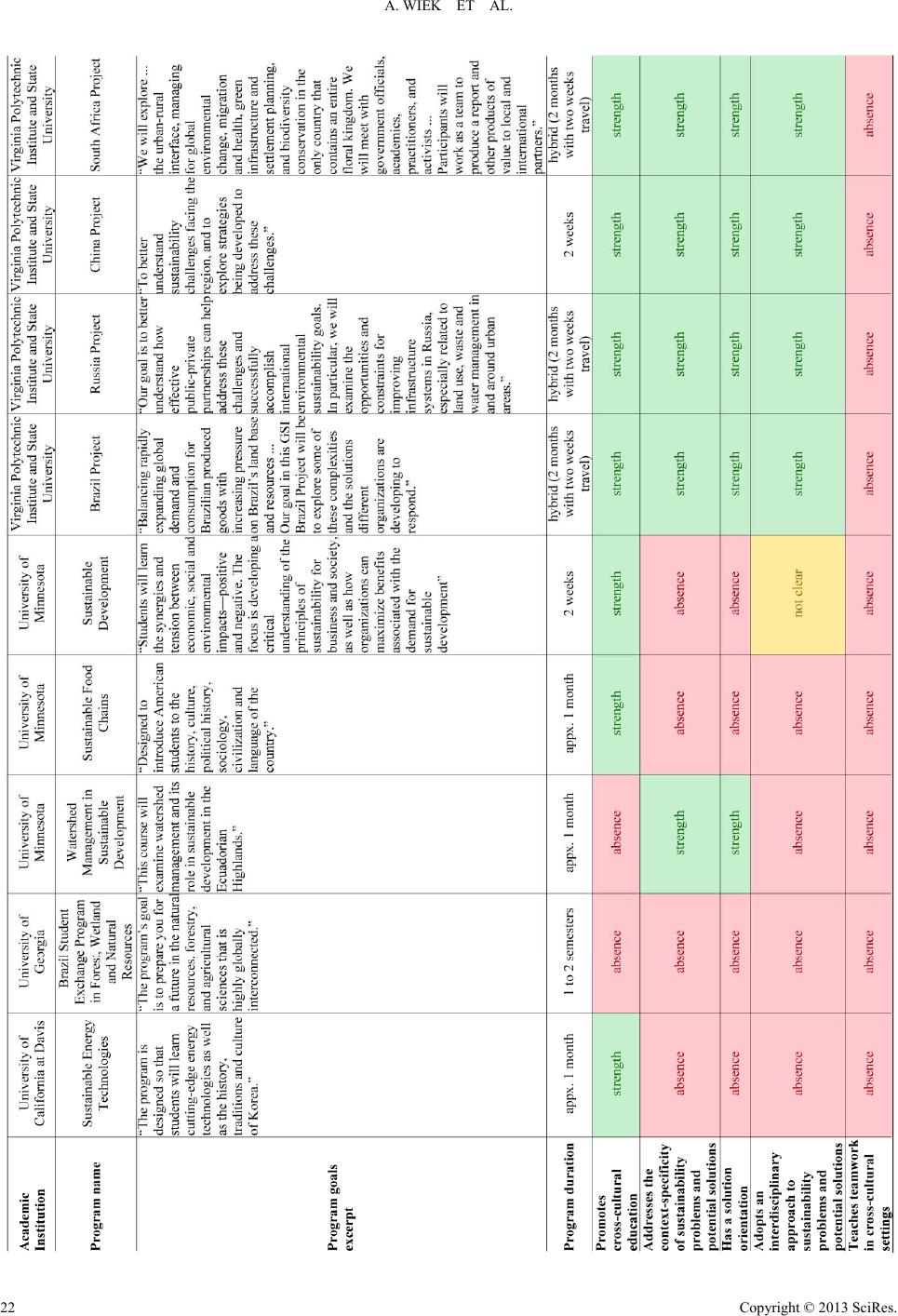

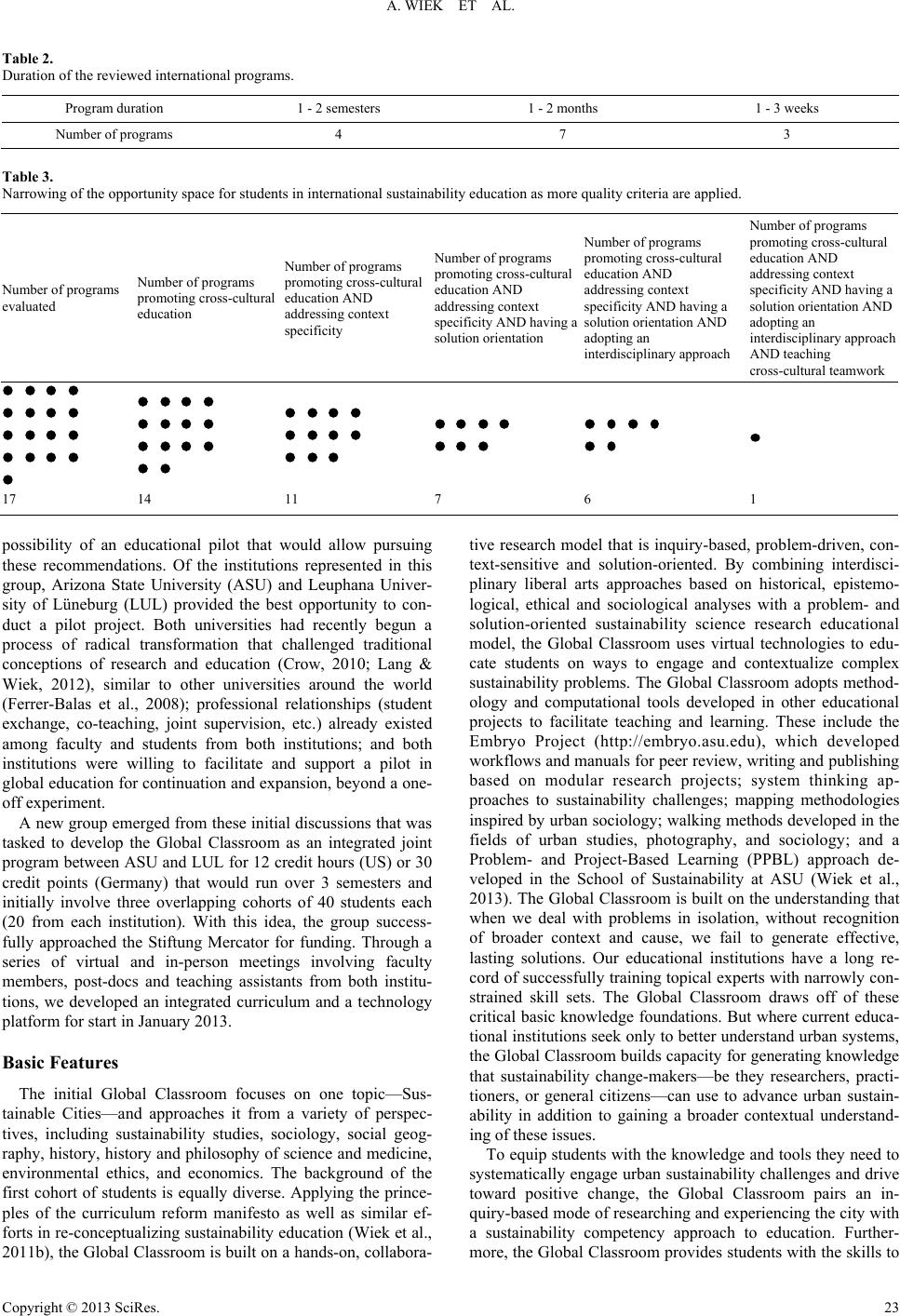

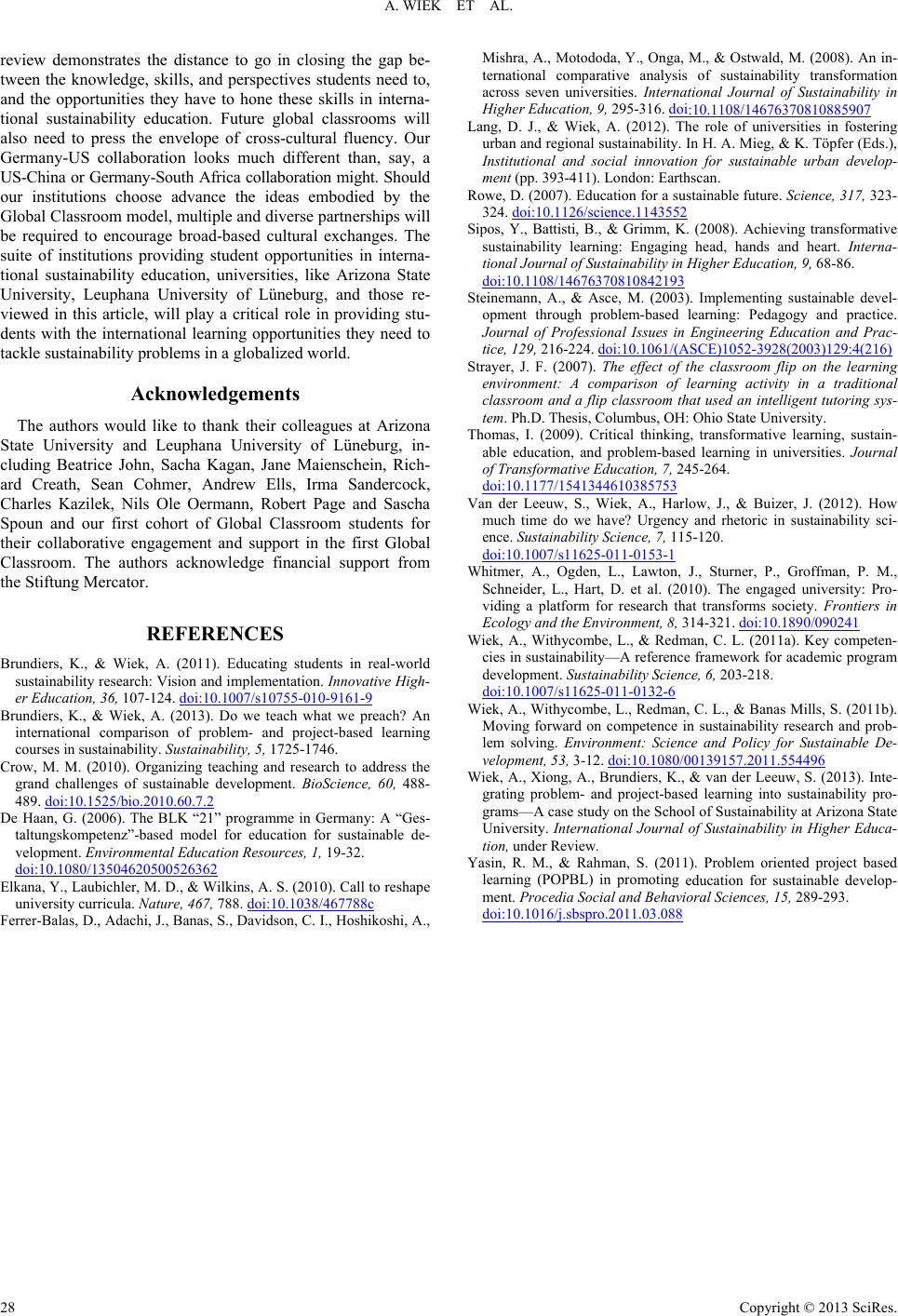

|