Open Journal of Political Science 2013. Vol.3, No.2, 59-68 Published Online April 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ojps) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojps.2013.32009 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 59 Electing an All-Party, Proportional, Power-Sharing Coalition, a Government of National Unity Peter Emerson The de Borda Institute, Belfast, Northern Ireland Email: pemerson@deborda.org Received January 23rd, 2013; revised February 27th, 2013; accepted March 9th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Peter Emerson. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attri- bution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. There are many instances when a group of people might want to choose a committee, a fixed number of individuals to undertake a particular collective function. At their AGM or annual conference, residents in a community group, shareholders of a limited company, members of a trades union, and those of a politi- cal party, may all want to elect an executive: one person to be chair, another secretary, a third treasurer, etc. All these posts require different talents and all the individual office bearers undertake necessary but separate functions for the successful operation of that committee. In like manner, a parliament may choose to elect a government of national unity (GNU). The only voting procedure so far devised by which a given electorate—those concerned at an AGM or members of parliament (MPs)—may elect, not only those whom they wish to be in cabinet, but also the ministerial posts in which each of those chosen will then serve, is the matrix vote. This paper describes 1) an experiment held at the Political Studies Associa- tion of Ireland (PSAI), undergraduate conference in Dublin on 23rd June 2012 in which participants, role playing as members of the Irish parliament, elected a GNU; and 2) the matrix vote methodology, such that others may also employ this voting system. An obvious instance would be for the election of an all-party power-sharing executive in a post-conflict zone. Keywords: Power-Sharing; Consensus; Modified Borda Count (MBC); All-Party Coalition Introduction “Democracy is for everybody, not just 50 per cent and a bit.” The matrix vote1 is a means by which any electorate may choose a fixed number of individuals, each of whom is to un- dertake a specific function, while all of whom are to co-operate for a common purpose. The methodology could be used, for example, for the AGM elections of executive committees by community groups, limited companies and trades unions. It could also be used for the election of: 1) an executive committee at the annual conference of a po- litical party2; 2) a majority coalition government by the parliamentary members of the parties involved (currently, in Ireland, Fine Gael (FG) and Labour); 3) the chairpersons of select committees in parliament and their equivalents in local councils; 4) governments of national unity, (GNUs), especially in plu- ral societies like Belgium and/or post-conflict zones such as Afghanistan and Zimbabwe. The peace process in many such zones often involves a form of power-sharing. In these jurisdictions, general elections are often held under a system of PR, in order to ensure that all the erstwhile opponents are then represented in parliament. Fair- ness in the democratic process is, thus far, achieved, for all the successful candidates have an equal status: they are all MPs. The problem comes when forming the government, for every cabinet minister will have a different status: one will be the prime minister, another the minister of finance, while yet an- other could be in what is considered to be a relatively unimpor- tant department such as that of culture and sport. The question, then, is how to elect a GNU, an all-party coalition cabinet such that, in the election: 1) Every MP is eligible to aspire to office; 2) Every MP is able to cast their preferences, and on an equal basis; While in the outcome: 3) Individually, each minister is appointed to that department for which, in the consensus of parliament, he/she is most suited; and 4) Collectively, the chosen ministers represent the entire par- liament in fair proportion to their party strengths. The methodology by which an electorate may elect such a team is the matrix vote. This paper will consider that which is potentially its most important function, namely, to facilitate the election by a parliament of a GNU; accordingly, all relevant references will apply to Dáil Éireann (the Irish Parliament). 1A full description of this methodology is in (Emerson, 2007: p. 61 et seq.). See also (Emerson, 2011: pp. 21-30). 2The matrix vote has often been used for this purpose by the Northern Ireland Green Party (NIGP). The said methodology enables every Teachta Dála, TD, (member of the Dáil) to choose, not only those whom they wish to be in cabinet, but also the particular ministry in which they  P. EMERSON wish each of their nominees to serve. The matrix vote is PR, so the outcome is (almost) bound to be a proportional, all-party, power-sharing coalition3. It should also be noted that the meth- odology is “ethno-colour blind” and, as such, is ideally suited for use in plural societies, especially in post-conflict jurisdic- tions. An Experiment Earlier experiments have examined the viability of the matrix vote when those concerned have voted as party blocks4. This latest exercise was designed to test whether or not the method- ology is robust, that is, to see how it might work even when individual voters (TDs) act independently of each other. The Candidates For the purposes of this experiment, a short list of only 26 TDs was produced, as shown in the annex to this paper; but a similar process would be expected to take place in real life, as each party chose its principal candidates. The 26, some of the more well known TDs, consisted of 12 Fine Gael (FG), 6 La- bour, 3 Fianna Fáil (FF), 2 Sinn Féin (SF) and 3 “independents”; and the number of 26 was chosen as the best small whole num- ber to represent the relative party strengths in due proportion. The Dáil is not, as yet, gender balanced, so nor was this short list; the balance in the latter, however, was strengthened. The Electorate The participants in the experiment were not representative of any national electorate, neither of the Dáil nor of the Irish population as a whole. There again, the purpose of the experi- ment was only to demonstrate that it is possible to identify a complex collective will, even from a group of disparate indi- viduals. Accordingly, each person present was asked to con- sider themselves to be an un-named, unidentified and unaffili- ated member of the current Dáil. The Ballot Paper It was assumed that parliament had already decided to elect a government of ten ministers, the specific departments being as listed on the ballot paper, as in Table 1. The voter (the first one is male), enters the names of those whom he wishes to serve in government in “The Cabinet” col- umn (shown in Table 1 in tint); his list of names is his choice of cabinet and even if he casts only a 1st preference, the vote is already deemed to be valid. In addition, for all of his nominees, he may choose the portfolio in which he wants each to serve; this he does by marking the relevant box in the matrix with a letter A. Thus a full ballot will consist of ten different names in the light-tinted “Cabinet” column, and then, in the matrix of the ballot, ten As, one in each column and one in each row. An example is shown in Table 2, with the As in a darker tint. In case a candidate elected to the cabinet could not be allo- cated to the department chosen by the particular voter—this would happen if another candidate had received a higher sum for, and was thus already appointed to, that ministry—the voter, (this one is female,) is also entitled to give any or all of her nominees a B and, if desired, a C as well. An example is shown in Table 3. The Voters’ Profile The total number of votes was 16. All of them were valid. All of the voters cast preferences for a full slate of 10 different names from the given short list. Most of the voters cast a num- ber of As, though not all cast a full slate of 10 As, and, with just one exception, every A cast was also valid (i.e., there was only one instance of two As in one row or one column). Four voters also cast some Bs and Cs. The Count A matrix vote works on the basis of two counts: the first is to identify the ten most popular individuals—these then make up the cabinet; and the second is to allocate each of these ten to a particular ministerial department. Both counts are conducted on just the one ballot, the one set of cast preferences. The former is held according to the rules of a quota Borda system (QBS) election5 (Emerson, 2007: p. 39 et seq.); and the latter, as per the rules of a modified Borda count (MBC)6 (Ibid: 15 et seq.). The QBS Count, in Theory As its name implies, success in a QBS election is based upon either a quota of high preferences and/or an MBC total7. The count proceeds in stages on the basis of the following three sets of data: the 1st preference totals for single candidates, the 1st/ 2nd preference totals for pairs of candidates8, and the MBC totals. Throughout the count, the procedure goes to a subsequent only if there are seats still to be filled. Stage 1. candidates with a quota of 1st preferences get elected; Stage 2. if a pair of candidates gets two quotas of 1st/2nd references, both candidates in the pair are elected. p 5In political circles and in any cross-community organisations, the recom- mended methodology is the QBS matrix vote, so the first count is under the rules of QBS, the second under those of MBC (see footnote 6). In those organisations where internal ethno-religious or even gender tensions are not so keenly felt, the simpler MBC matrix vote may be used, in which case both counts are conducted under MBC rules. 6In an MBC, if there are n options/candidates, the voter may cast m prefer- ences, where 1 ≤ m ≤ n. Points are awarded as per the rule (m, m − 1 … 1). Thus he who casts only one preference gives his favourite 1 point; she who casts two preferences gives her favourite 2 points (and her second choice 1 point); and so on. The voter is thus incentivised—but not forced—to cast a full ballot. Evidence suggests that the BC, as originally envisaged by Jean-Charles de Borda, was in fact an MBC (Saari, 2008: p. 197; Emerson, 2013: pp. 353-358). 7A candidate’s MBC total is the addition of all his/her sums plus any unal- located points, i.e., those points where the voter has cast a preference for this particular candidate but has not cast an A for a ministerial post for this nominee. 8If x people give Jean a 1st preference and Joan a 2nd preference; if y people give Joan a 1st preference and Jean a 2nd preference; and if x + y >2 quotas then the Jean Joan air is said to have two uotas E erson 2007: . 41 . 3The matrix vote is based on the quota Borda system (QBS), which like roportional representation—single transferable vote (PR-STV), is oportional according to the wishes of the voters. That is to say, if a quota of individuals decides to vote for all women or all anti-nuke candidates, then one such candidate is bound to be elected. In other roportional systems, PR-list, proportionality is based on party labels only. 4In 2009 under the last Dáil, the de Borda Institute ran an experiment in which participants acted as if they were members of the relevant political parties: FF, FG, GP, Lab, Progressive Democrats and SF (Emerson, 2011: pp. 21-30). Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 60  P. EMERSON Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 61 Table 1. A matrix vote ballot paper The Portfolios The Cabinet Names of Candidates in Order of Preference: Taoiseach (PM) Department of Finance Department For- eign Affairs and Trade Department Of Education A nd Skills Department of Jobs, Entep rise and Innovation Department of Defence Department of Justice and Equal- ity Department of Health Department of Environment, Community an Local Govt Department of Arts, Heritage and the Gaetac ht 1st 2nd 3rd 4th 5th 6th 7th 8th 9th 10th Table 2. A full ballot—an example The Portfolios The Cabinet Names of Candidates in Order of Preference: Taoiseach (PM) Department of Fi nan ce Department Foreign Affairs and Trade Department Of Education And S kills Department of Jobs, Enterprise and Innovatio n Department of Def en ce Department of Justice and Equality Department of He alt h Department of Environment, Community and Local Govt Department of A rts, Heritage and theGaetacht 1st Jean A 2nd Jim A 3rd Jane A 4th Joe A 5th Joan A 6th Jan A 7th James A 8th John A 9th Jo A 10th Jill A  P. EMERSON Table 3. A full ballot—another example The Portfolios The Cabinet Names of Candidates in Order of Preference: Taoiseach (PM) Department of Finance Department For- eign Affairs and Trade Department Of Education A nd Skills Department of Jobs, Enterprise and Innovatio n Department of Defence Department of Justice and Equal- ity Department of Health Department of Environment, Community and Local Govt Department of Arts, Heritage and the Gaeltacht 1st Jean C B A 2nd Jim A C B 3rd Jane A C B 4th Joe A 5th Joan A B C 6th Jan B A C 7th James A B C 8th John B A 9th Jo A 10th Jill A Elected candidates are not counted in any further calculations. Stage 3. if a pair of candidates gets a single quota of 1st/2nd preferences, the more popular, i.e., the one with the Higher MBC total, is elected; Stage 4. candidates are chosen on the basis of their MBC totals. There are no transfers and no eliminations in QBS; further- more, all preferences cast are taken into account9. The QBS Count, in Practice The valid vote was 16. The number of persons to be elected was 10. Therefore the quota was 2. Stage 1. Joan Burton came first with 7 in number 1st prefer- ences. Enda Kenny and Micheál Martin came joint second, so, based on their MBC totals, the former came second and the latter third; Stages 2-3. there were no pairs with 2 quotas, and no pairs with 1 quota10; Stage 4. the remaining seats were awarded on the basis of the MBC totals. The results of the QBS count, the ten persons chosen to form the cabinet, are shown in Table 4. The MBC Count, in Theory Once the ten most popular candidates have been thus identified, the second count takes place, and this is based on the MBC sums, i.e., the number of A points each candidate has received for any one specific department. These sums are then consid- ered, in descending order, allocating in turn each of the ten cabinet members to a specific ministry. If at any time there is a draw between two sums, consideration is given first to the more popular candidate, as measured in the QBS election; and if there is still a draw, priority is given to that ministerial post for which the MBC total was the greater. This last item of data is shown in the bottom row of Table 5 only. It gives an indication of the degree of importance to which the electorate regard each department. The discrepancy between the two overall totals— 873 and 555, in the bottom right hand corner—is because of the 318 points which were cast by the voters for unsuccessful can- didates. The MBC Count, in Practice The matrix is as shown in Table 5, and successful candidates are now appointed to the various ministries in accordance with the sums received. The highest of all, 55—shown in Table 5 in blue—means (Joan) Burton gets Finance. The next highest is 40, also in blue, so Quinn takes on Education. Then comes 33— (Richard) Bruton for Finance, but this post is already allocated; the 33 total of A points is thus redundant, so Bruton’s votes are examined to see if any of these are transferred into B points … and sure enough, 9B points support his candidacy for Health. Redundant sums are shown in yellow, and transferred sums are in green, as in Table 6. The next highest sum is 30 for Burton for Taoiseach (Prime Minister), but she is already in Finance, so this 30 also becomes redundant, with no transfers required as the individual con- cerned has already been appointed. Next comes the sum of 25, of which there are two, but it is an uncontested tie because one sum of 25 gives Gilmore Foreign Affairs and the other 25 allo- cates Higgins to the Jobs department. The next sum, 23, is again Gilmore’s, so this is also redundant, with no transfers required. Then comes 21, for Mary L. McDonald to get De- fence. 9For a comparison of PR-STV and QBS, see (Emerson, 2010: pp. 197-209). 10Pairs of candidates are more likely to occur when participants are acting in blocs. The count continues, and the next highest sum is 20, as shown in Table 7. In this instance both Kenny and Martin are Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 62  P. EMERSON Table 4. The QBS results. The Cabinet Names of Elected Candidates Party 1st Preference Totals1st/2nd Preference Totals QBS Results MBC Totals Joan Burton FG 7 - 1st 108 Enda Kenny FG 2 - 2nd 48 Micheál Martin FF 2 - 3rd 26 Pat Rabbitte Lab 1 - 4th 67 Eamon Gilmore Lab 1 - 5th = 65 Ruairí Qui nn Lab - - 5th = 65 Kathy Lynch Lab - - 7th 52 Mary L. McDonald SF 1 - 8th = 43 Joe Higgins Ind - - 8th = 43 Richard Bruton FG 1 - 10th 38 Table 5. The first MBC matrix The Portfolios The Cabinet QBS Count Names of Elected Candidates Taoiseach (PM) Department of Finance Department Foreign Af- fairs and Trade Department Of Education And Skills Department of Jobs, En- terprise and Innovation Department of Defence Department of Justice and Equality Department of Health Department of Environ- ment, Community and Local Govt Department of Arts, Heri- tage and the Gaeltacht Unallocated As MBC totals 1st Joan Burton 30 55 13 9 1 108 2nd Enda Kenny 20 6 8 11 3 48 3rd Micheál Martin 20 6 26 4th Pat Rabbitte 10 8 15 13 10 4 3 4 67 5th = Eamon Gilmore 23 25 3 8 4 2 65 5th = Ruairí Quinn 7 40 7 4 7 65 7th Kathy Lynch 9 7 13 8 1 11 2 1 52 8th = Mary L McDonald 10 7 21 3 2 43 8th = Joe Higgins 1 25 3 9 3 2 43 10th Richard Bruton 33 4 1 38 555 Total numbers of points cast: 133 132 99 84 79 72 88 73 51 54 8 873 rivals for the post of Taoiseach, so this tie is definitely con- tested. It is however easily solved: Kenny is the QBS more popular cabinet member, so he gets this post. Martin’s A points are therefore transferred as per his B points, and so to Table 8. Next comes 15, Rabbitte for Foreign Affairs, but that is al- ready allocated. His 13 for Education is also redundant, as is Lynch’s which is for Education and Burton’s for Justice. Rab- bitte’s 15 and 13 are examined for any B points, and he gets 6 for Justice; from her own A points, Lynch does not get any B points; while Burton’s votes are not examined for B points because she has already been appointed. Then comes 11: Kenny’s is redundant, Lynch’s 11 appoints Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 63  P. EMERSON Table 6. The second MBC matrix The Portfolios The Cabinet QBS Count Names of Elected Candidates Taoiseach (PM) Department of Finance Department Foreign Aff airs and Trade Department Of Education And Skills Department of Jobs, Enter- prise and Innovation Department of Def en ce Department of Justice and Equality Department of He alt h Department of Environmen t, Community and Local Govt Department of A rts, Herita ge and the Gaeltach t Unallocated As 1st Joan Burton 30 55 13 9 1 2nd Enda Kenny 20 6 8 11 3 3rd Mcheál Martin 20 6 4th Pat Rabbitte 10 8 15 13 10 4 3 4 5th = Eamon Gilmore 23 25 3 8 4 2 5th = Ruairí Quinn 7 40 7 4 7 7th Kthy Lynch 9 7 13 8 1 11 2 1 8th = Mary L. McDonald 10 7 21 3 2 8th = Joe Higgins 1 25 3 9 3 2 10th Richard Brton 33 4 9 1 Table 7. The third MBC matrix The Portfolios The Cabinet QBS Count Names of Elected Candidates Taoiseach (PM) Department of Fi nan ce Department Foreign Affairs and Trade Department Of Education An Skills Department of Jobs , Enterpris e a nd Innovation Department of Def en ce Department of Justice and Equality Department of He alt h Department of En vir onm e nt, Community and Local Govt Department of Arts, Heritage and the Gaeltach t Unallocated As 1st Joan Burton 30 55 13 9 1 2nd Enda Kenny 20 6 8 11 3 3rd Micheál Martin 20 10 6 4th Pat Rabbitte 10 8 15 13 10 4 3 4 5th = Eamon Gilmore 23 25 3 8 4 2 5th = Ruairí Quinn 7 40 7 4 7 7th Kathy Lynch 9 7 13 8 1 11 2 1 8th = Mary L. McDon- ald 10 7 21 3 2 8th = Joe Higgins 1 25 3 9 3 2 10th Richard Bruton 33 4 9 1 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 64  P. EMERSON Table 8. The fourth MBC matrix The Portfolios The Cabinet QBS Count Names of Elected candidates Taoiseach (PM) Department of Finance Department Foreign Affairs and Trade Department Of Edu- cation And Skills Department of Jobs , Enterpris e a nd In- novation Department of De- fence Department of Justice and Equality Department of Health Department of Environment, Community and Local Govt Department of Arts, Heritage and the Gaeltach t Unallocated As 1st Joan Burton 30 55 13 9 1 2nd Enda Kenny 20 6 8 11 3 3rd Micheál Martin 20 10 10 6 4th Pat Rabbitte 10 8 15 13 10 4 6 3 4 5th = Eamon Gil- more 23 25 3 8 4 2 5th = Ruairí Quinn 7 40 7 4 7 7th Kathy Lynch 9 7 13 8 1 11 2 1 8th = Mary L McDonald 10 7 21 3 2 8th = Joe Higgins 1 25 3 9 3 2 10th Richard Bruton 33 4 9 9 1 her to Health, which renders Bruton’s 9B points redundant, and he gets 9C points instead for the Environment. We move on to the next highest matrix sum, which is 10. Mar- tin’s sum of 10B points for Foreign Affairs is redundant, so he gets 10C points for Jobs. But this too is redundant. Rabbitte’s two 10 s are also redundant, but he gains no more B points. McDonald’s 10 is redundant as well, as are Burton’s 9, Lynch’s 9 and Higgins’ 9. Almost done: Table 9. Bruton’s 9 for Environment now comes into play. We move on to 8: Kenny’s, Gilmore’s and Lynch’s 8s are all redundant, as is Rabbitte’s, but only Rab- bitte’s 8 is eligible for a transfer of B points, he being the only one of these four individuals not yet appointed. When it comes to 7, Quinn has three of them, while Lynch and McDonald both have one; but all of these 7 s are redundant. Thus it is the sum of 6 which sees the final two appointments: Martin to Arts and Rabbitte to Justice. The final result, therefore, as shown in Table 10, is an all-party coalition of 1 FF, 3 FG, 1 Ind, 4 Lab and 1 SF. An Analysis As noted above, the electorate was not in any way represen- tative. And while the voters were able to talk to each other, most proceeded to act independently: indeed, not one ballot resembled another, not even in their 1st and 2nd preferences, let alone in all ten. In such a matrix vote, a voter may choose any one of 26 can- didates for her 1st preference; any one of 25 for her 2nd; any one of 24 for her 3rd, and so on. In other words, there are 26!/16! > 19 × 1012 different ways of voting. In theory, then, in an un-whipped Dáil, the chances of any one ballot being even similar to another would be slim. Now the more choices the individual TDs have, the more dif- ficult it is for any party leader or whip to control his/her par- liamentary party. Accordingly, the matrix vote is ideally suited to a free vote. Granted, the electorate in this experiment—16 persons—was small. Nevertheless, the above evidence suggests that this sys- tem is capable of application, no matter how many members are in the parliament, no matter how (small or) large the number of ministers to be appointed to cabinet. The Psychology of the Matrix Vote In any matrix vote election for a GNU cabinet of ten minis- ters, in a parliament of, let us say, four parties—W, X, Y and Z, with 40, 30, 20 and 10 per cent of the seats—each party could expect to win 4, 3, 2 and 1 seats respectively of such an execu- tive. Any W party TD, therefore, could well want to cast four or maybe five preferences for her own party colleagues, but would be wise to cast any other preferences for those whom she con siders to be the best from the other parties. Such a course of action is to her advantage because, as suggested earlier (see footnote 6), an MBC incentivises the voter to cast a full slate of ten preferences. Overall, then, the said TD will have more chance of getting her favourite candidates elected if she casts all ten preferences; and more chance of influencing the final outcome if she votes on a cross-party basis. This is the foundation stone of the ma trix vote, but it is also, surely, the core of any multi-party coali- ion: that TDs talk with each other, and that they vote with each t Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 65  P. EMERSON Table 9. The penultimate MBC matrix The Portfolios The Cabinet QBS Count Names of Elected Candidates Taoiseach (PM) Department of Finance Department Foreign Affairs and Trade Department Of Education A nd Skills Department of Jobs, Enter prise and Innovatio n Department of Defence Department of Justice and Equality Department of Health Department of Environment, Community and Local Govt Department of Arts, Heritage and the Gaeltacht Unallocated As 1st Joan Burton 30 55 13 9 1 2nd Enda Kenny 20 6 8 11 3 3rd Micheál Martin 20 10 10 6 4th Pat Rabbitte 10 8 15 13 10 4 6 3 4 5th = Eamon Gilmore 23 25 3 8 4 2 5th = Ruairí Quinn 7 40 7 4 7 7th Kathy Lynch 9 7 13 8 1 11 2 1 8th = Mary L. McDonald 10 7 21 3 2 8th = Joe Higgins 1 25 3 9 3 2 10th Richard Bruton 33 4 9 9 1 Table 10. The outcome, the final matrix The Portfolios The Cabinet QBS Count Names of Elected Candidates Party Taoiseach (PM) Department of Finance Department For- eign Affairs and Trade Department Of Education A nd Skills Department of Jobs, Enterprise and Innovatio n Department of Defence Department of Justice and Equality Department of Health Department of Environment, Community and Local Govt Department of Arts, Heritage and the Gaeltach t MBC totals 1st Joan Burton FG 55 108 2nd Enda Kenny FG 20 48 3rd Micheál Martin FF 6 26 4th Pat Rabbitte Lab 6 67 5th = Eamon Gilmore Lab 25 65 5th = Ruairí Quinn Lab 40 65 7th Kathy Lynch Lab 11 52 8th = Mary L. McDonald SF 21 4 8th = Joe Higgins Ind 25 43 10th Richard Bruton FG 9 38 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 66  P. EMERSON other. The former interaction will be more likely if the struc- tures for the latter are already in place. Indeed, this inclusive methodology will probably encourage co-operation, just as the procedures laid down in the Belfast Agreement led to “the de- partmental allocations [being] agreed in advance” (Wilford, 2009: p. 186). In the above experiment, because some voters made use of their Bs and Cs, no one cabinet member was appointed to a ministry by default, i.e., by being the last person left for the one remaining department. The chances of such under the present arrangements in the Belfast Agreement are actually quite high11, and while a similar case is always possible with a matrix vote, the prospects in a full Dáil of any one minister being appointed to a ministry for which he/she has no support (a sum of zero) are minimal. Indeed, experience suggests that the use of inclu- sive voting procedures like the MBC and QBS can be the very catalyst of consensus. Conclusion In 2008, at the beginning of the most recent financial crisis in Ireland, there were many calls for a GNU. There was next to nothing, however, on a methodology by which such a cabinet could be (s)elected. Many other countries have had similar calls: the UK had a GNU during the slump and again in WWII; some Belgians were asking for a GNU during their recent protracted paralysis on government formation—it eventually took them 541 days; Greece in its present fiscal difficulties has also heard such sug- gestions, and so on. There have also been calls for power- sharing and unity governance in many plural societies, espe- cially those which have endured internal conflicts: Afghanistan, Bosnia, Cyprus, Egypt, Honduras, Iraq, Kenya, Lebanon, Libya, Northern Ireland and Zimbabwe, to name but a few. Those which have decided to form a GNU have usually relied on a purely verbal process, and often these discussions have been problematic and protracted; Iraq, for example, took 249 days (Emerson, 2012: p. 173). Only one country has moved to a form of permanent all-party governance without first suffering a crisis, namely, Switzerland, where use is made of a mechanism called a magic formula12. Other attempts at devising a mechanism by which a GNU might be chosen have been seen in some conflict zones but, in many instances, sectarianism has often, in effect, thus been institutionalised. The arrangements of the Belfast Agreement, for example, are one of a few reasons why it “remains grounded in the very structures it aspires to transcend” (Taylor, 2009: p. 320); the Agreement uses both party labels and designations. In similar fashion, Bosnia uses ethno-religious distinctions, while Lebanon differentiates on the basis of confessional beliefs. As noted in the introduction, however, the matrix vote, in contrast, is “ethno-colour blind”. It is fair, it is proportional, and it is suitable for any post-conflict society because it caters for all in that society on a non-sectarian basis; furthermore, it will cater for all in the future, when hopefully any ethno religious tensions will be less prominent. The matrix vote is the only voting procedure so far invented by which an electorate—a parliament—may elect a fixed num- ber of persons to form a team, a committee, a cabinet—a gov- ernment—such that each elected member has a different status, as chosen by that electorate. In essence, therefore, it is ideally suited for any society which aspires to a more inclusive polity. The chances that this methodology might find application, not only in Dublin and Belfast, but in other jurisdictions too, are therefore high Acknowledgements Thanks are due, first of all, to the Political Studies Associa- tion of Ireland (PSAI) in general, but especially to Claire McGing thereof, who so arranged the postgraduates’ confer- ence as to facilitate the experiment and who was at all times most accommodating. Secondly, I wish to acknowledge the work of my colleague in the de Borda Institute, Phil Kearney, who is one of four government appointees in the current senate of National University of Ireland (NUI); he was the main driv- ing force behind the first Dublin-based experiment in 2009, and he was here again to assist in the count. I should also add that others involved in 2009, including Professor John Baker of UCD, have given their continued support and interest in this voting methodology. Finally, I would like to thank the partici- pants at the conference who all took part in the exercise with such enthusiasm and good humour. References Emerson, P. (2007). Designing an all-inclusive democracy. Heidelberg: Springer. Emerson, P. (2010). Proportionality without transference: The merits of the quota Borda system. Representation, 46, 20-31. Emerson, P. (2011). The matrix vote: Electing an all-party coalition cabinet. Voting Matters, 29, 197-209. doi:10.1080/00344893.2010.485820 Emerson, P. (2012). Defining democracy. Heidelberg: Springer. Emerson, P. (2013). The original Borda count and partial voting. Social Choice and Welfare, 40, 353-358. Saari, D. (2008). Disposing dictators, demystifying voting paradoxes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511754265 Taylor, R. (2009). The injustice of consociationalism. In R. Taylor (Ed.), Consociational theory. Londen: Routledge. Wilford, R. (2009). Consociational government. In R. Taylor (Ed.), Consociational theory. Londen: Routledge. 11The bigger parties take it in turns to appoint the executive of ten ministers. 12In 1959, Switzerland initiated a collective presidency called the Swiss Federal Council, and party nominees are appointed to this body based upon a Zauberformel of 2:2:2:1 ratio among the four largest parties. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 67  P. EMERSON Annex 1 Short List of 26 TDS Short List of Potential Ministers FINE GAEL (12) FIANNA FÁIL (3) SINN FÉIN (2) Richard Bruton Micheál Martin Gerry Adams Simon Coveney Éamon Ó Cuiv Mary Lou McDonald Lucinda Creighton Willie O’Dea Jimmy Deenihan Frances Fitzgerald “INDEPENDENTS” (3) Phil Hogan LABOUR Joan Collins Enda Kenny Joan Burton Joe Higgins Nicky McFadden Eamon Gilmore Maureen O’Sullivan Michael Noonan Brendan Howlin James Reilly Kathleen Lynch Alan Shatter Ruairí Quinn Leo Varadkar Pat Rabbitte Abbreviations BC: Borda Count. DUP: Democratic Unionist Party. FF: Fianna Fáil. FG: Fine Gael. GP: Green Party. GNU: Government of National Unity. Ind: Independent. Lab: Labour. MBC: Modified Borda Count. MLA: Member of Legislative Assembly (NI). MP: (= TD) Member of Parliament. NI: Northern Ireland. NIGP: Northern Ireland GP. NUI: National University of Ireland. PR: Proportional representation. PR-STV: PR—Single Transferable Vote. PSAI: Political Studies Association of Ireland. QBS: Quota Borda System. SDLP: Social Democratic Labour Party. SF: Sinn Féin. STV: Single Transferable Vote. TD: (= MP) Teachta Dála (Member of Dáil Éireann, the Irish Parliament). UUP: Ulster Unionist Party. Definitions All-party: the term “all-party” implies all the larger parties, but it does not exclude any of the smaller parties or even any independent TDs. Sum: for the purposes of this article, a “sum” is the number of points a candidate gets for any one specific ministerial de- partment. Total: while a total refers to all the points a candidate re- ceives—i.e. a total is the addition of all his/her sums (plus per- haps any un-allocated points—see footnote 7). Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 68

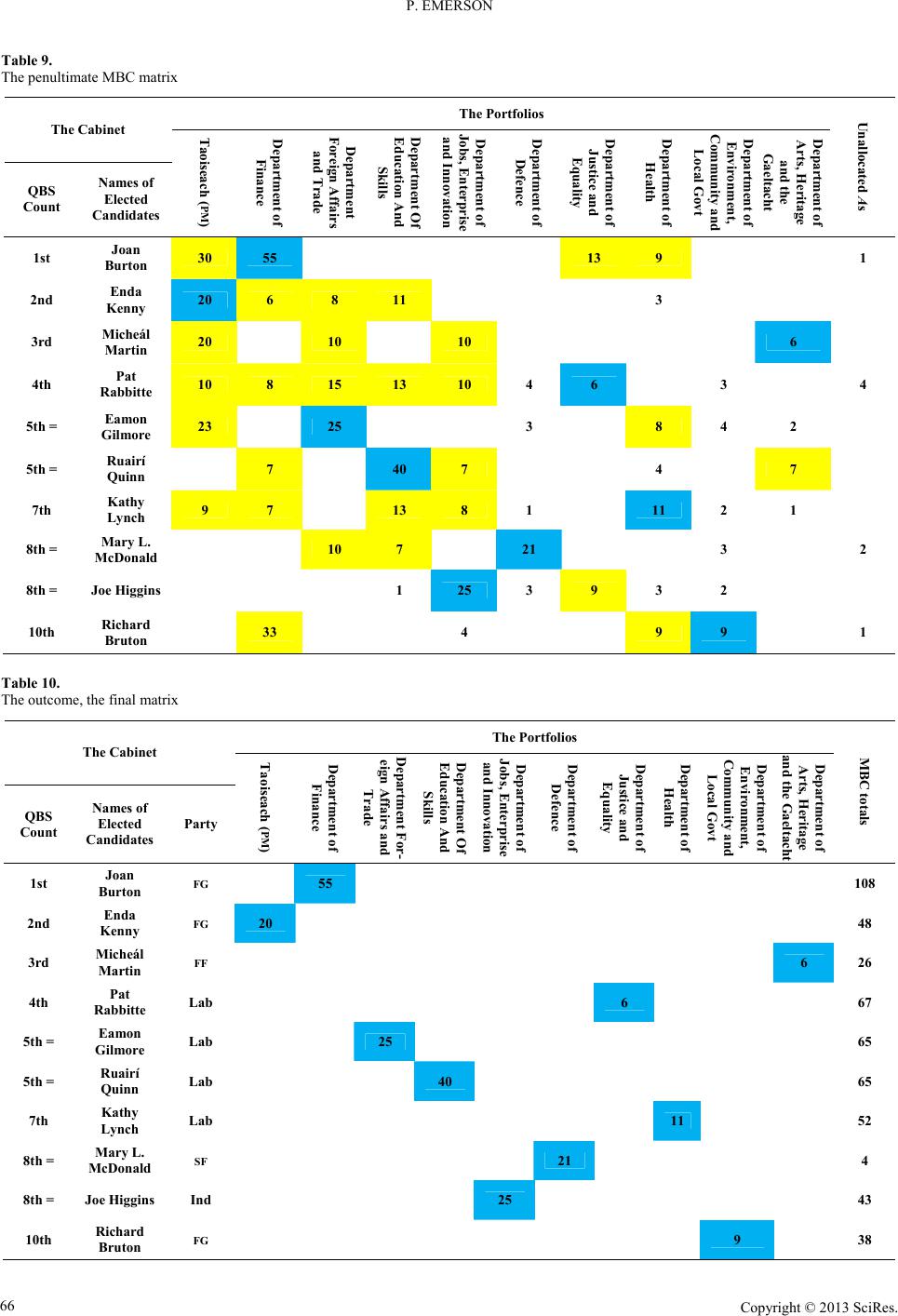

|