Open Journal of Modern Linguistics 2013. Vol.3, No.1, 9-19 Published Online March 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ojml) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojml.2013.31002 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 9 Thematic and Lexical Repetition in a Contemporary Screenplay Starling Hunter1, Susan Smith2 1Tepper School of Business, Carnegie Mellon University in Qatar, Do ha , Q at ar 2School of Mass Communication, American Univer sity of Sharjah, Sharjah, UAE Email: starling@qatar.cmu.edu Received October 21st, 2012; revised December 5th, 2012; accepted December 12th, 2012 Several works on film theory and screenwriting practice take up the question of repetition within narrative. However, few if any, have articulated theories about the relationship between the repetition of the words that comprise the screenplay itself and repetition of the themes that lend coherence to the narrative. In this study we address this gap in the screenwriting and film literature. Specifically, we analyze repetition of words and themes in the screenplay of Sunshine Cleaning, a critically-acclaimed independent film. Based on our survey of the literature, we expect and we find several varieties of repetition among words associ- ated with the major themes in SunshineCleaning. This repetition includes but is not limited to polyptoton (words formed by inflections, declensions, and conjugations of a common stem), homonymy, paregmenon (words sharing a common derivation), and compounding (words formed by combining two or more words). We further expect and find that the repetition of words linked to themes is extensive and found in the large majority of the scenes of the screenplay. Finally, we expect and find that words associated with the themes are repeated far more frequently than in a random sample of screenplays contained within the Corpus of Contemporary American English. We conclude the paper with a discussion of our study’s im- plications for the art and craft of screenwriting. Keywords: Narrative Structure; Narrative Repetition; Narrative; Rhetoric; Morphology; Etymology; Screenplay; Screenwriting Introduction Academic studies of the role of repetition within narrative are numerous, encompassing countless cultures and language groups, written and oral traditions, literary and linguistic genres. The subjects of these investigations include, but are not limited to, novels (Suleiman, 1983; Sprague, 1987; Shostak, 1995; Fahy; 2000), folktales (Yen, 1973, 1974; Seydou, 1983; Nad- daff, 1991; Pinault, 1992; Luthi, 1992), epic poetry (Culbert, 1963; Lord, 2000; Reich, 2006); the Old and New Testaments (Capel, 1994; Walsh, 2001; Bullinger, 2003); comic strips (La- cassin, 1972), short stories (Toolan, 2008), children’s fantasies (Botvin & Sutton-Smith, 1977), oral personal histories (Blum- Kulka, 1993; Yemenici, 2000) and the narrative discourses of indigenous peoples (Somsonge, 1992; Brody, 1986; Axelrod & Garcia, 2007) and elderly Alzheimer’s patients (Moore & Dav- is, 2002). Within the cinematic arts, repetition within narrative has been considered in a wide variety of contexts including early American cinema (Auerbach, 2000), contemporary action films (Higgins, 2008), experimental feminist film (Smith, 2008), adapted screenplays (Turner, 1977), soap operas (Nochimson, 1997), westerns (Browne, 1975), dramas (Sadkin, 1974), docu- mentaries (Robson, 1983), horror films (Briefel, 2009) and the boxing genre (Grindon, 1996). The subject has also been taken up in works on film production (Bellour, 1977) and the art and craft of screenwriting (e.g. Horton, 2000; Parker, 2002; Nor- man, 2007; Cunningham, 2008). Generalizing across these many and varied domains is ex- ceedingly challenging: investigations can and do differ accord- ing to which elements of a narrative are repeated, where they are repeated, and how often. One characteristic common to this research is the focus on great works and classics. But this pref- erence also limits generalization because it strongly favors in- depth analyses of a few texts over less detailed comparisons of multiple texts. That said, we believe that research in one of the above fields hold particular relevance for the cinematic arts— narrative theory, particularly that applied to folklore. A central concern of that field is the relationship between narrative struc- ture and theme, i.e. “any unifying idea or image, which is re- peated and developed throughout a literary work” (The Literary Encyclopedia, 2012). We recognize in the literature on folkloric narrative several concepts and methods similar to those de- scribed in works on film theory and screenwriting practice. Of special interest are those theories and concepts concerning the repetition of certain words and its relationship to the repetition and development of themes central to the narrative. In this paper we apply several such concepts to the study of Megan Holley’s Sunshine Cleaning, a critically-acclaimed in- dependent film directed by Christine Jeffs and starring Amy Adams (Julie and Julia), Emily Blunt (My Summer of Love), and Alan Arkin (Little Miss Sunshine). To paraphrase Toolan (2008), a major goal of this study is to derive a skeletal version of the story—one comprised of themes and the words that rein- force them and one that includes the key events and character arcs. Drawing from research on the narrative structure of folk- lore and of screenplays, as well as the conceptual vocabulary of classical rhetoric, we develop herein three propositions con- cerning the repetition of themes and of words associated with them. Respectively, these propositions concern 1) how words associated with themes are repeated 2) where they are repeat ed and 3) how often they are repeated. We then empirically test these three propositions on the text of the screenplay of Sun- shine Cleaning.  S. HUNTER, S. SMITH How Are Words Associated with Themes Repeated? If there is one point of agreement among the many studies of repetition in narrative, it is that themes, however defined, are repeated in different ways and places in a story. Words—both as dialog and description—are invariably included among the ways that this repetition is manifested. However, it is rare to find more than anecdotal evidence offered in support of this point, let alone thoroughgoing theories. For example, in an essay entitled The Values of Close Analysis, Andrew (1971) makes a compelling case for the in-depth and systematic study of narrative structure in transcribed “film scripts”. The principal benefits he anticipated were the possibility of scrutinizing “the sequence of events”, the “catalouging of interrelationships be- tween fragments scattered throughout the film”, and an en- hanced understanding of patterns in dialog, narrative structure, and image “clustering” (pp. 49-51). Yet, he did not specify what form the sequences, fragments, patterns, and clusters could take, let alone what relationships, if any, they could or should bear to one another. A second example comes from Robson’s (1983: p. 45) study of the narrative structure of Grey Gardens. Repetition is essen- tial to four “recurrent themes” that he says characterize the lives of the mother and daughter protagonists, Big Edie and Little Edie. Although Robson arranges the themes into several “clus- ters of antinomies”, each of which is “linked with an often elaborate network of visual and verbal references”, only two examples are provided. The most relevant one concerns how the subtheme of modesty and promiscuity is underscored by “repeated references to clothing” (ibid). But beyond noting Little Edie’s insistence upon wearing girdles, Robson does not place references to girdles within the context of other refer- ences to clothing. Nor does he indicate what relationship those articles have to one another or to the four recurring themes. A third example comes from Bordwell & Thompson’s (2008: p. 49) best-selling textbook, Film Art—An Introduction. The authors devote an entire chapter to the significance of “film form”, a term they define as “a unified set of related, interde- pendent elements” and “the overall system of relations that we can perceive among the elements in the whole film”. They also def i ne five principles which “help create relationships a mong the parts” and which “the spectator perceives in a film’s formal system”. These are “function, similarity and repetition, differ- ence and variation, development, and unity/disunity”. Con- cerning the second of these they state: Repetition is basic to our understanding any film. For in- stance, we must be able to recall and identify characters and settings each time they reappear. More subtly, through- out any film we can observe repetitions of everything from lines of dialogue and bits of music to camera posi- tions, characters’ behavior, and story action (61). Bordwell and Thompson use the term “motif” to describe these manifold “formal repetitions” and define it as “any sig- nif i ca n t re p eated element in a film” including, but not lim it e d t o , “an object, a color, a place, a person, a sound, or even a char- acter trait” (2008: p. 61). Despite offering several examples of the repetition of motifs, discussion of the relationship of words to the repetition of motifs is cursory. The closest that the au- thors come is this sidebar quotation from Robert Towne, the screenwriter of Chinatown: You can take a movie, for example, like Angels with Dirty Faces, where James Cagney is a child and say s to his pal Pat O’Brien, “What do you hear, what do you say?”— cocky kid—and then as a young rough on the way up when things are going great for him he says, “What do you hear, what do you say?” Then when he is about to be executed in the electric chair and Pat O’Brien is there to hear his confession, he says, “What do you hear, what do you say?” and the simple repetition of the last line of dia- log in three different places with the same characters brings home the dramatically changed circumstan ces muc h more than any extensive diatribe would (ibid). While more examples could be provided, these three suffice to confirm our earlier assertion concerning the repetition of words in support of themes and other elements of film form: the repetition of words—whether as dialogue or description—is recognized as very important, but evidence to support this claim is mostly anecdotal and largely atheoretical. While work in the field of narrative folklore is similarly an- ecdotal, one advantage it provides our investigation is its con- ceptual vocabulary, namely the terms it employs to distinguish between different types and functions of repetition within nar- rative. For example, in the book Story-telling Techniques in The Arabian Nights, Pinault (1992) describes four forms of repe- tition in narrative—repetitive designation, leitwortstil, thematic patterning and formal patterning, and dramatic visualization. They are summarized and described by El-Shamy (1996: p. 187) as follows: Repetitive designation: repeated references to some char- acter or object that appears insignificant when first men- tioned but which reappears later to intrude suddenly on the narrative. Leitwortstil (or leading word): a concept borrowed from Biblical studies that denote “a word or word root that re- curs significantly in a text, in a continuum of texts, or in a configuration of texts; by following these repetitions, one is able to decipher or grasp a meaning of a text.” Thematic patterning and formal patterning: “The struc- ture is disposed so as to draw the audience’s attention to certain narrative elements over others. Recurrent vocabu- lary, repeated gestures, accumulation of descriptive p hr as es around selected objects: such patterns guide the audience in picking out particular actions as important in the flow of narrative.” Dramatic visualization: “The representing of an object or character with abundance of descriptive detail, or the mi- metic rendering of gestures and dialogue in such a way as to make the given scene ‘visual’ or imaginatively present to an audience.” Another of Pinault’s definitions of thematic patterning is “the distribution of recurrent concepts and moralistic motifs among the various incidents and frames of a story” (1992: p. 22). He asserts that in “skillfully crafted” tales, this technique empha- sizes “the unifying argument or salient idea which disparate events and disparate narrative frames have in common” (ibid). That description strongly echoes the one given for “theme” by Yen (1973: p. 163), i.e. “a recurrent description or incident with varying degrees of verbal correspondence in repeated sections Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 10  S. HUNTER, S. SMITH of a narrative”. In his study of Japanese folktales, Yen (1974: p. 2) employs “story-pattern” or “thematic-pattern” analysis, a me- thod that “abstracts a group of essential and frequently recur- ring elements from a narrative and formulates them in a mean- ingful sequence of configuration.” His analysis of one Japanese folktale, The Listening Hood, describes what he calls a “typical example of oral narrative” because it demonstrates repetition on many distinct levels. The first of these is the “formulary lan- guage level” where he describes what Lord (1960: p. 145) called “word-for-word correspondence”: the description of the girl’s recovery—“the daughter’s ill- ness began to disappear day by day, like the peeling off of layers of thin paper”—is repeated in the rich man’s re- covery—“the master’s illness then began to disappear day by day like the peeling off of layers of thin paper.” Yen also finds repetition on the “thematic” level where a “composition unit” about a conversation among crows is paral- leled shortly thereafter by another conversation among tree spirits. Finally, Yen also finds repetition on the “thematic-pat- tern” level where the recurrence of eight themes—poverty, journey, sleep, otherworld, knowledge, return, sickness, and reward—comprises the narrative. One thing is apparent from the above examples: compared to research in the cinematic arts, research on narrative folklore has given more detailed attention to defining terms and concepts describing the repetition of themes and words. From this re- search we expect that the repetition of words associated with themes will take several forms. Our first proposition is that these forms will include: 1) repeated references to characters and objects 2) recurring words and word roots 3) recurrent vo- cabulary and descriptions of objects 4) abundant descriptive detail and 5) the “word-for-word correspondence” and “mi- metic rendering” of dialogue. Where Are Words Associated with Themes Repeated? Also emphasized in the above definitions is information about the location of the various forms of repetition. For exam- ple, another of Pinault’s definitions of thematic patterning is “the distribution of recurrent concepts and moralistic motifs among the various incidents and frames of a story” (1992: p. 22). He continues, stating that in “a skillfully crafted tale, the- matic patterning may be arranged so as to emphasize the unify- ing argument or salient idea which disparate events and dispa- rate narrative frames have in common” (ibid, emphasis added). In Writing Your Screenplay, Dethridge (2003: p. 50) draws a distinction with similar implications. She distinguishes between the “central” or primary theme of a screenplay, the one she calls the “premise”, and subsidiary or secondary themes. The premi se is “the overall concept that governs the story” and, she tells us: the most difficult theoretical element to discuss, as it represents one of the most ethereal aspects of the writing. The writer must have the patience or the focus to identify a premise in their own work. The premise is often invisi- ble to the audience. Rather than being stated baldly or acted out... (the premise) works at a subliminal or sub- conscious level to help convey a strong idea that goes be- yond concrete action into the realm of feeling or mood. Think of your premise as the central, most important theme. It’s an idea which will be repeated again and again in different ways throughout the script (ibid, emphasis added). Dethridge also discusses the relationship of subsidiary sec- ondary themes to the premise. She states that “the strongest stories” are built “around a well-organized set of themes which help to cement the premise and to imbue the story and charac- ters with flavor or attitude”. She illustrates this point using The Silence of the Lambs, a film in which “metamorphosis” is the central theme, a premise invisible yet present “in every scene” (150). Dethridge further underscores this point when she asserts that any randomly-picked scene in a screenplay “can be read as a kind of sample or miniature, scaled-down version of the entire screenplay... because each scene will reflect the larger tone, mood, premise and themes of the screenplay” (ibid, emphasis added). Based on the literature reviewed in this and the preceding subsection of the paper, our second proposition is that words associated with key themes should be repeated in the large ma- jority of scenes in the screenplay, if not all of them. How Often Are Words Associated with Themes Repeated? One point of agreement among screenwriters and film theo- rists concerns the limited number of themes a screenplay ought to contain—very few. For Mehring (1990) the number is one: in Body and Soul it’s “self-respect”, in Beverly Hills Cop it’s “chutzpah”, and in Rebel without a Cause it’s “responsibility”. For Field (2005), the number i s small. In The Royal Tenenbaums he identifies three themes—“family, failure, and forgiveness”. In Chinatown and Pulp Fiction, the number drops to one. In the former the theme is “water” and it is, he writes, “an organic thematic thread, woven through the story”. In the latter, the theme is “revenge”. Dethridge’s (2003) analysis of The Silence of the Lambs identifies one premise or central theme—“meta- morphosis”—and three secondary themes, each having to do with the idea of gaining or taking on a “new life”. Notably, the themes in each above example are different. But of course, this is to be expected—each belongs to a different genre, e.g. boxing, action, comedy, drama, mystery, film-noir, etc. The premise behind film genre is that it is possible to cate- gorize films according to similarities among their narrative elements (Langford, 2005). Although the number and names of genres is constantly evolving, the two dozen or so provided in The Internet Movie Database are broadly representative of typologies developed by scholars of this subject. The existence of so many distinct gen- res has an interesting implication for this study. Since themes can be one of the narrative elements used to classify films into genres, then there should be a high similarity of themes and associated words within a genre and lower similarity across genres. For example, words like jab, punch, gloves, ring, bell, trainer, ropes, decision, opponent, and knock-out should be more common in the boxing genre than in other genres. Simi- larly, films whose theme is revenge or water or metamorphosis should contain many more words associated with these themes than do films with different themes. Thus, our final proposition is as follows: the observed fre- quency of words associated with primary and secondary themes significantly exceed the expected frequency of those same Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 11  S. HUNTER, S. SMITH words in a representative sample of contemporary screenplays. As far as we are aware, no prior research on repetition within the narrative of screenplays has considered such specific propositions as the three posited here. Before detailing our methodological approach, we first provide a plot summary and an overview of the main characters. Characters & Plot Summary Sunshine Cleaning is the first screenplay written by Megan Holley and thus far the only one to be produced (Holley, 2007). Directed by Christine Jeffs (Rain) and filmed in Albuquerque, New Mexico, this independent film was nominated for the Grand Jury Prize at the Sundance Film Festival and for Best Supporting Actress by the London Critics Circle. According to The Internet Movie Database the film also won an award for Outstanding Achievement in Casting-Low Budget Feature from the Casting Society of America. Nine characters appear in five or more of the 175 scenes in the “Green Revision” of the screenplay. In order of appearance they are: Rose Lorkowski (Amy Adams), the protagonist and founder of the eponymous Sunshine Cleaning; Joe Lorkowski (Alan Arkin) her father; Norah Lorkowski (Emily Blunt), her sister; Oscar Lorkowski, her 7-year-old son; Carl Swanson, the owner of Clean Sweep, a rival cleaning firm; “Mac” Macdowell, (Steve Zahn), Rose’s former high school boyfriend; Randy, Norah’s itinerant boy- friend; Winston, the owner of a cleaning supply company and Rose’s mentor; and Lynn Wiseman (Mary Lynn Rajskub), the daughter of a client and Norah’s girlfriend. In short, Rose has gone from a high school cheerleading captain dating the quarterback to single mother cleaning houses, attending night classes, and having an affair with a married police officer, Mac. Her sister, Norah, is a disaffected and un- der-achieving waitress still living at home with their father, Joe. An obstinate middle-aged salesman still hoping to get rich quick, Joe doggedly hawks “Fancy Corn” to candy stores and shell fish to restaurants in between purchases of scratch cards. When Oscar, Rose’s son, is expelled from public school for abnormally mischievous behavior, Rose can’t afford private alternatives. To raise funds, she puts real estate classes on hold, opting instead for work as a biohazard removal and crime-scene cleaner. With moral support from Joe, job leads from Mac, guidance and supplies from her mentor, Winston, and the un- steady assistance of Norah, Rose launche s Sunshine Cleaning. As the operation evolves, the sisters face several difficult and unexpected circumstances. These involve everything from do- mestic disturbances, burning houses, highway accidents, and bereaved parents to the disposal of bloody remains and ques- tions of professional ethics and qualifications. Confronted al- most daily by the loss of life, Norah and Rose are eventually forced to deal with the still-lingering after-effects of their own family tragedy—their mother’s suicide some twenty years ear- lier. Doing so reconstructs an important family tie and brings a newfound measure of fulfillment in their personal lives. Methodology As a practical matter, methods for finding themes in stories vary widely. Methods recommended by film theorists range from the “close analysis” of key scenes and sequences (An- drew, 1971; Mehring, 1990), of frequently-used objects (Seger, 2010), and of oft-repeated lines of dialog or description (Bord- well & Thompson, 2008). In order to find themes in short-sto- ries, Toolan (2008) compared the “prominent repetition” of keywords with their base rates in a reference corpus. This tech- nique is very common in corpus linguistics and in the burgeon- ing sub-field of corpus stylistics (Hoover, 2002) but as of yet, it has not been applied to the analysis of screenplays. We begin our analysis by noting that at least well-known two figures of speech correspond directly to Pinault’s forms of re- petition and Yen’s “verbal correspondence”. For example, Pin- ault’s definition of leitwortstil is very similar to that for poly- ptoton, a figure of speech defined in the Encyclopedia Britan- nica as “the rhetorical repetition within the same sentence of a word in a different case, inflection, or voice or of etymologi- cally related words in different parts of speech.” Examples include verbs repeated in different moods and tenses, e.g. have and had, verbs and their cognate nouns, e.g. compute and com- puter, and nouns repeated in different numbers e.g. horse and horses. Another figure of speech similar to leitwortstil is pareg- menon, defined by Bullinger (2003: p. 304) as “the repetition of words derived from the same root”. Grindon’s (1996: p. 66) analysis of the boxing genre makes an excellent case for the applicability of paregmenon to film studies. Working from the premise that film “genres trade on the expectations of the viewer… (and) promise a particular emotional response” he posits that “the characteristic emo- tions elicited by the boxing film are nostalgia and pathos.” But unlike prior studies of the boxing genre, Grindon uses etymol- ogy to relate these two words to recurring themes. After assert- ing that “a bittersweet longing for the past finds expression in the boxing film in multiple ways”, Grindon insightfully ob- serves that “nostalgia finds its etymological root in the Greek words for home and pain; pathos has a close relationship, as its Greek etymology is rooted in the word for suffering. Bearing witness to suffering is central to spectatorship in the boxing genre” (ibid). Inspired by Field’s (1998) discussion of title and theme in The Silence of the Lambs, our thematic analysis starts with the two words comprising the title—“sunshine” and “cleaning”. And following Grindon’s (1996) discussion of etymological roots in the boxing genre, we begin our search for themes with roots of the three stems of the title words—sun, shine, and clean. According to The American Heritage Dictionary of Indo- European Roots (AHDIER), the word “sun” descends from the Indo-European (IE) root sawel-which means “the sun” (Wat- kins, 2000). Its derivatives include helium, solar, sun, and south. The latter two of those appear in the screenplay. According to the Online Etymological Dictionary (Harper, 2012), “shine” descends from the Old English scinan which means “shed li- ght, be radiant”. The stem is found twice in the screenplay—in the compound sunshine and as the adjective shiny. The same source also has clean descending from the Old English claene which means “clean, pure”. Several variants are found in the screenplay—cleaner, cleaners, cleaning, and cleans. These ety- mological roots and derivatives are displayed in Figure 1, be- low. The title, Sunshine Cleaning, appears in the top box. Be- neath are three boxes, one for each stem, its root, and deriva- tives of that root appearing in the screenplay. Taken as a group, the derivatives of the three stems exhibit both forms repetition mentioned in the first proposition. Firstly, polyptoton is present: among these derivatives we find inflec- tions, declensions, and conjugations of the three stems, e.g. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 12  S. HUNTER, S. SMITH Figure 1. Roots and derivatives of the three stems. shine and shiny, clean and cleans. Secondly, we find several derivatives of each etymological root present in the screenplay. Notably, several of these are compound words, e.g. sunshine, sunroom, and sunlight. Identifying Themes In order to identify recurrent themes associated with the three stems, we first ask what conceptual, grammatical, semantic, or other relationships, if any, exist among them. One such rela- tionship is fairly obvious: the word sunshine is a closed com- pound comprised of the stems sun and shine. An analogous but much less obvious relationship exists between “shine” and “clean”. That relationship involves another closed compound— “purblind”—a combination of the words “pure” and “blind”. According to the Compact Oxford English Dictionary the word previously meant “completely blind” but now means “partially sighted” and “lacking in discernment or understanding”. Nota- bly, the “pure” in “purblind” means “utterly” not clean but it descends from the IE root peu- meaning “to purify; cleanse”. The word “blind” is highly polysemous. Its many definitions span four parts of speech—verb, noun, adjective, and ad- verb—and fall into the three broad categories: the lack of sight, i.e. impaired visual acuity; deficient insight, i.e. impaired dis- cernment, reason, evidence, forethought, information, percep- tion, understanding; and concealment or covering, i.e. a hiding place and/or that which hinders, shuts out, and/or deprives of light or sight. The word “blind” descends from the Indo-Euro- pean root bhel-1, “to shine, flash, burn; shining white & various bright colors.” What we have in “purblind”, then, is a com- pound whose first half descends from a root meaning “to cleanse” and whose second half descends from a root meaning “to shine.” Thus, while the compound “sunshine” links “sun” and “shine” explicitly while the compound “purblind” links “shine” and “clean” implicitly. This subtle dichotomous relationship is pregnant with the- matic potential, as much as any of the numerous examples pro- vided earlier. In the two compounds “sunshine” and “purblind” we have outer light and inner darkness, sight and blindness, insight and ignorance among many possible antinomies. Indi- vidually, each could constitute a premise. Taken together they might comprise the “well-organized set of themes” around which the story is structured (Dethridge, 2003: p. 150), the “ne t wo r k ” o f r e pe a t ed “verbal references” (R obson, 1983: p. 45 ) that create “relationships” among the many elements of film form (Bordwell & Thompson, 2008). In order to determine whether this is the case, we examine the etymological roots of seven related words—the three stems (sun, shine, and clean), the two linking compounds (sunshine, purblind), and two addi- tional stems (pure, blind). We begin by recalling that sun descends from the Indo- European (IE) root sawel- which means “sun” and that shine descends from the Old English scin an, “shed light, be radiant.” Somewhat surprisingly, nine IE roots include the word shine in their definitions: the roots aus-, bha-1, dyeu-, ghel-2, and kand- each mean “to shine”; the root bhel-1 means “to shine, flash, burn”; bherg- means “to shine, bright, white; and the definitions of arg- and bhel-1 both refer to “shining white”, i.e. silvery, and other bright colors. Several derivatives of seven of these roots appear in the screenplay including argument, fancy, black, bleach, glad, glass, incense , strawberry, and white. As it pertains to the third stem, just one IE root explicitly connotes “clean.” That root is peu- and it means “to purify; cleanse”. Its derivatives include pour, purblind, pure, puree, purge, puritan, and purity. Among these, only the verbs pour and pours appear in the screenplay. In Table 1, below, the first column contains the three initial stems. The second column shows the roots with which each stem is associated. Eleven of these thirteen roots have derivatives that appear in the screenplay. Those deriva- tives are listed in the third column. To identify additional Indo-European roots associated with the compound sunshine we begin with its synonyms. Interest- ingly, Roget’s 21st Century Thesaurus contains no entry for “sunshine” itself. The word does, however, appear as a syno- nym of four others—day, daylight, light, and the drug LSD. The word “day” descends from the root the IE root agh- which means “a day considered a span of time”. Other derivatives of agh- include dawn and the compound words daylight and today. Another IE root possessing a synonymous meaning is ayer- (day, morning). The word “light” is linked to two IE roots— leuk- (light, brightness) and legwh- (light, having little weight). Table 2, below, contains two columns. In the first are the above four roots and their definitions. The second column lists deriva- tives of these roots that are found in the screenplay. The aforementioned sense of “pure” has nine single-word synonyms in Roget’s 21st Century Thesaurus—blasted, com- plete, confounded, infernal, mere, sheer, thorough, unmitigated, and unqualified. Eight Indo-European roots associated with these synonyms are displayed in the second column of Table 3 below. The third column lists the derivatives of these roots that appear in the screenplay. Recall that the first two aspects of “blind” concerned “sight” and “insight”. Roget’s 21st Century Thesaurus lists 16 single- word synonyms for “sight” as a noun meaning the “ability to see with the eyes” and another twenty for “insight” as a noun meaning “intuitiveness, awareness”. Although there is much overlap in the two lists, twenty-two synonyms descending from sixteen IE roots were identified. In Table 4, below, the second column displays these synonyms while the third column lists the roots from which they descend. Across from each root, in the fourth column, are listed its derivatives found in the screen- play. The third aspect of “blind” concerns both concealment and covering. The former descends from the IE root kel-1 (t o cove r, Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 13  S. HUNTER, S. SMITH Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 14 Table 1. Roots and derivatives associated with three stems. Stem Root (definition) Derivatives in the screenplay sun sawel (the sun) south, sun, sunshine, sunroom, sunlight shine scinan (shed l ight, be radiant) shiny, sunsh ine shine arg (to shine, white; the shining or white metal silver) argument shine aus (to shine) shine bha-1 (to shine) fancy, fantastic, fantasy, phase shine bhel-1 (to shine, flash, burn; shining white & various bright colors) black, blanches, blank, bleach, blinds, bl ond, blue, flames, strawberry, flashes, flashlight shine bherg (to shine, bright, white) bright, brightly shine dyeu (to shine) shine ghel-2 (to shine; colors, bright materials) glad, glance, glances, glares, glass, glasses, glows, gold, golden, yellow shine kand (to shine) incense shine kwe it (white; to shine) white clean claene (clean, pure) clean, cleaner, cleaners, cleaning, cleans clean peu (to purify, cleanse) pour, pours Table 2. Roots and derivatives associated with synonyms of “sunshine”. Roots (definition) Derivatives in the screenplay agh (a day) day, days, today Ayer (day, morning) early, or legwh (light, having little weight) carnival, lightly, lighten, relieve d Leuk (light, brightness) illustrated, lit, l ights, flashlight, headlights, hi g hlighted, sunlight Table 3. Roots and derivatives associated with synonyms of “pure”. Synonyms Root (definition) Derivatives unmitigated ag (to drive, do) act, action, actually , agent, exactly, examine, examines, examining, reaction, reacts, squatter, transaction blasted bhle (to bl ow) blast, blow, flavoring unqualified dhe (to set, put) benefit, defeat, defeated, difficult, face, faced, faces, fact, factor, features, office, officer, perfect confounded gheu (to pour, pour a libation) confused, confusion, found, foundation, trust funder, infused, profound infernal ndher (unde r) under, und erstand, understa nding, unde r- whelmed, underbelly, underneath complete pele-1 (to fill, abundance, multitude) complete , completed, completely, fill, filled, full, supplies, supply Mere smer-2 (to get a share of somethin g) Merely thorough tere-2 (to cross over, pass through, overcome) through, trunk conceal, save). Several of this root’s derivatives appear in the screenplay including cell, colored, discolored, and holding. The later descends from the root wer-4 (to cover). Only one of its derivatives appears in the screenplay—coveralls. Two Indo- European roots have synonymous definitions: skeu - (to cover, conceal) and steg- (to cover). Table 5 summarizes the roots and derivatives associated with “conceal” and “cover”. Thus far, we have identified 43 roots and 267 derivatives as- sociated with the two compounds (sunshine and purblind) and five stems (sun, shine, clean, pure, and blind). This was accom- plished by first relating stems of the title to one another through a compound word (sunshine) and then relating them through a second compound formed from derivatives of associated ety- mological roots. This process resulted in a large and wide range of words being associated with the title. The number is cer- tainly wider than we would have obtained had we confined the analysis to inflections of the three stems. And while quantity is not the objective of this analysis, the large number of words associated with the title and with each other suggests the pres- ence of something more than mere repetition. At a minimum, the 267 deri vatives could be t he raw material from which repetition in narrative is constructed, the kind of repetition called thematic patterning, leitwortstil, verbal corre- spondence, repetitive designation in the literature on folkloric narrative. As such, we will at this juncture identify four themes derived from the above analysis—daylight, purity, sight/insight, and conceal/cover. Repetition of these themes is evidenced by the occurrence in the screenplay of the derivatives found in Tables 2-5, respectively. The Distribution of Derivatives across Scenes In our second proposition we argued that the repetition of  S. HUNTER, S. SMITH derivatives would be extensive, as measured by their presence in the large majority of the screenplay’s 174 scenes. As we expected, this proposition is also strongly supported: 163 of the 174 scenes contain one or more derivatives—nearly 94%. The average is 5.3 derivatives per scene with twenty-one derivatives being the most contained in any one of them. Other aspects of the distribution of the derivatives across the scenes reveal much about their role in the narrative. Twenty-three scenes contain 11 or more derivatives—over twice the average. These scenes were easily grouped according to one or more story or thematic pat- terns, as described by Pinault (1992) and by Yen (1974). In addition, these patterns are supported by repetition of related derivatives. For example, in Scene 28 Oscar, Rose’s son, dis- covers and shows considerable interest in his late grand- mother’s binoculars. Unfortunately for Oscar they have much sentimental value for his grandfather, Joe, who takes them away after Oscar nearly damages them. In Scene 162 Oscar gets the binoculars as his 8th birthday present. The word bin- ocular and binoculars appear a total of sixteen times in the screenplay, fourteen of which are found in these two scenes. They descend from the roots dwo- (two) and okw- (to see). The latter was one of several roots associated with the theme sight/insight. This is a clear example of Pinault’s (1992) “re- petitive designation”, i.e. “repeated references to some charac- ter or object), of leitwortstil, i.e. “a word or word root that re- curs significantly in a text”, of “thematic patterning”, i.e. “re- current vocabulary”, and an “accumulation of descriptive phra- ses around selected objects”. Other equally significant instances are evident among the 23 scenes. In Scenes 40 and 52 belong depict Joe, Rose’s father, in the course of his work as an independent salesman. In Scene 40 we find him at a local bar discussing sales of the latest product he is hawking—“Fancy Corn”. In Scene 52 we see him on a sales call, trying to convince a candy store owner to stock “Fancy Cor n ” an d to p ro mo t e i t a s “ wh o l e so me ” a n d as a “health food”. When the store owner balks at this suggestion, Joe signals Oscar to deploy a ruse to convince the store owner that there is growing demand for the product. Derivatives of two etymo- logical roots are common to both scenes—sak- (to seek out) and sta- (to stand). Both of these roots were previously shown to be associated with the sight/insight theme. One derivative of the former root is found in both scenes—sake. In both scenes the word is part of dialog spoken by Joe, dialog that evidences repetition extending beyond the word itself. Specifically, in scene 40 Joe uses the word in a discussion with a regular bar patron about the pace of “Fancy Corn” sales: “It’ll get there. Takes time to get to know the market. Develop a relationship with the buyers. But it’ll get there. Who doesn’t like popcorn for Christ’s sake.” In Scene 52, he uses the word again in the same context, this time when speaking to the store owner: Table 4. Roots and derivatives associated with synonyms of “sight” and “insight”. Theme Synonym Roots Derivatives Appearing in the Screenplay SIGHT afterimage aim (copy) image, imaginable, imagine INSIGHT acumen ak (sharp) acumen, heaven, heavens SIGHT appearance apparere (to come forth, be vi sible) appear, appears, disappear, disappears INSIGHT judgment deik (to show, pronounce solem nl y) condition, index, indicates, indicating, teacher, teachers, teach, teaching, toes, toke INSIGHT wavelength del-1 (long) long, alon g, belong, lounges SIGHT apprehension ghend (to seize, take) forgotten, guess, pregnant, reprieve SIGHT ken gno (to know) acknowledging, acknowledgement, acquainted, can, could, enormous, ignore, ignores, kne w, know, knowing, known, knows, knowledge, normally, note, notes, notice, noticed, not ices, recognition SIGHT apperception, perception kap (to grasp) accept, anticipation, behavior, catch, catches, chases, chasing, concept, cop, except, heavy, occupies, receive, receiver , recovery INSIGHT discernment krei (to sieve, discriminate, distinguish)concern, crime, critical, excrement, secretary SIGHT eye, eyes, eyeshot, eyesightokw (to see) binocular, binoculars, eye, eyeballs, eyebrow, eyelash, eyes, window, windows INSIGHT sagacious sag (to seek out) sake SIGHT seeing sekw-2 (to pe r ceive, see) saw, see, see i n g , seen, sees, sight, si ghts SIGHT observing spek (to observe) self-respecting, expecting, expect INSIGHT understanding sta (to stand) assistant, circumstances, distance, distant, real estate, resist, rest, restaurant, restaurants, res t s , s tand, standing, stands, state, s tation, statue , stay, steady, st eering, stool, store, stores INSIGHT wavelength webh (to weave, to move quickly) wave, waves, weaves SIGHT view, viewing, vision, visibility weid (to see) advice, envied, guidelines, guy, guys, histo r y, idea, ideas, provides, stories, story, supervise, surveys, visit, TV Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 15  S. HUNTER, S. SMITH Table 5. Roots and derivatives associated with “conceal and cover”. Roots Derivatives in Sunshine Cleaning kel-1 (to cover, conceal, save) asshole, cell, colored, discolored, doghouse, hallway, hold, holding, holds, hole, house, warehouses skeu- (to cover, conceal) hose, hut, recoils, sky steg- (to cove r) detective, detective s , p r ot ective, tile wer-4 (to cover) over, coveralls JOE: Read that. The manager leans close. MANAGER: High fructose-- JOE: No. The first thing listed. The number one ingredient. MANAGER: Corn. JOE: Exactly. Corn. Can you think of anything more wholesome? It’s all American for Christ’s sake. The manager’s not buying it. Oscar takes action. He posi- tions himself next to the girl. Recall earlier that the root sta- was related to the sight/insight theme by way of the word “understanding”, one of the syno- nyms of “insight”. Four derivatives of sta- appear five times in Scenes 40 and 52: understand, restaurants, stool, and store. Another eight scenes depict Rose as she manages and oper- ates her cleaning service. In Scenes 60 and 61 Rose and Norah make their first visit to Winston’s cleaning supply store where they get advice and information about competitors along with their purchase. In Scene 73, she brings Oscar with her and proudly shows Winston the logo that Oscar made for her new business cards. Winston also gives Rose advice on how to market her service to funeral homes and insurance companies. In Scene 76 Rose buys a van for carrying her equipment and supplies while Scenes 89 and 91 find her and Norah arriving at a home where an elderly man has earlier committed suicide. Rose tenderly comforts the grief-stricken widow as she waits for a family member to arrive. Scenes 132 and 151 are closely linked, as well. In the former, while preparing to attend Paula’s baby-shower, Rose receives a call from a State Farm insurance agent offering her a rush job. In what turns out to be a major lapse in her judgment, Rose sends Norah alone to start the job, promising to arrive after she leaves the shower. In Scene 151, when Rose does finally arrive, she finds the whole house ablaze, fire trucks surrounding it, and learns that Norah’s carelessness was the cause. As shown in Table 6, below, 62 derivatives of 30 roots are repeated 107 times in these eight scenes. The relationship of the roots and derivatives to their parent themes is readily apparent, the most strongly emphasized theme being, once again, sight/ insight. Specifically, 27 derivatives associated with thirteen roots are found 37 times in these eight scenes, an amount far more than with any other theme or stem. Frequency Distribution of the Derivatives Recall that our third proposition predicted that the observed frequency of words associated with themes would exceed the average or expected frequency. In other to determine these expected values, we turned to Davies (2009, 2012) Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA). According to its creator, that corpus is “the largest freely-available corpus of English, and the only large and balanced corpus of American English” (Davies, 2012). The corpus is “equally divided among spoken, fiction, popular magazines, newspapers, and academic texts” and contains over 400 million words, twenty-million each from 1990-2009 (ibid). The fiction texts in the COCA are further divided into several sub-categories including Science Fiction/Fantasy, Juvenile, General-Journalism, General-Books, and Movies. The 267 derivatives identified above appear 975 times in the screenplay of Sunshine Cleaning—nearly 5% or one in every twenty of the 20,432 words. According to the Movies sub-cate- gory of the COCA, the expected frequency of these words in a screenplay of this length is 581 times or just 2.8% of the total. The latter is over 70% lower and a highly significant difference statistically. Figure 2 below plots the observed versus expected frequencies of the derivatives by stem and theme. In every in- stance the observed frequency is much higher than expected. The differences range from a low of just 28% for the deriva- tives associated with “pure” to a 900% difference for deriva- tives associated with “clean.” Statistically, all of these differ- ences are highly significant for a screenplay with 20,432 words. Notably, the highest percentage differences are found among the first three stems—sun, shine, and clean. It is also notewor- thy that the derivatives associated with the “sight” and “insight” appear far more often than those associated with any other theme. Also, the repetition of words associated with that theme is very extensive: the 388 appearances of these 123 related derivatives are found in 123 of the screenplay’s 174 scenes— just under 71%. Taken together, these results strongly support the third propo- sition, i.e. that the observed frequency of words associated with major themes exceeds that associated with the typical contem- porary screenplay. Recall that we expected this because of the relationships of theme and words to genre. That makes the dif- ference one of kind rather than quality. That is to say, we would expect any screenplay belonging to an identifiable genre to differ significantly from a representative sample of screenplays from many genres. What is noteworthy, however, is that we have a significantly higher number of words being repeated in support of the themes—over 400—most of which would not have been identified by any other methods than those described here. Conclusion Earlier in this paper we offered three propositions concerning the form, extensiveness, and frequency of the repetition of w or ds associated with this screenplay’s themes. As expected, we found strong support for all three. Regarding the first proposition , Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 16  S. HUNTER, S. SMITH Table 6. Recurring them es , roots an d derivatives in eight scenes depicting rose at wor k. Source Stem or Theme Root Derivatives Occurrences of Derivatives title sun sawel (the sun) sun, sunshine, sunlight, sunroom 7 title shine bha-1 (to shine) Fancy 1 title shine bhel-1 (to shine, flash, burn) Blue 3 title shine ghel-2 (to shine; colors) glasses, golden, yellow 3 title shine kweit (white; to shine) White 2 title clean claene (clean, pure) clean, clean-up, cleaner , cleaners, cleaning 14 title clean peu (to purify, cleanse) Pours 2 sunshine daylight ayer (day, morning) Earlier 1 sunshine daylight legwh (light, having little weight)Lightly 1 sunshine daylight leuk (light, brightness ) Sunlight 1 purblind pure ag (to drive, d o) actually, exactly 2 purblind pure dhe (to set, put) difficult, doing, does, done 7 purblind pure pele-1 (to fil l , abundance) full, supply, supplies 8 purblind pure tere-2 (to cross over, p ass through )Through 2 purblind insight aim (copy) Image 1 purblind insight ak (sharp) heaven, heavens 2 purblind insight deik (to show) Indicates 2 purblind insight ghend (to seize, take) Forgotten 1 purblind insight gno (to know) note, notice, noticed, notices 4 purblind insight kap (to grasp) Recovery 1 purblind insight krei (to sieve, disc riminate) Crime 1 purblind insight okw (to see) eye, window, windows 4 purblind insight sekw-2 (to pe rceive, see) Sight 1 purblind insight spek (to observe) Expect 1 purblind insight sta (to stand) rests, stand, stands, stay, state farm, steering wheel, store 13 purblind insight webh (to weave) Waves 1 purblind insight weid (to see) TV, guidelines, s urveys 5 purblind cover/conceal kel-1 (to cover, conceal, save) hold, holds, house, 13 purblind cover/conceal skeu (to cover, conceal) hose, pantyhose 2 purblind cover/conceal steg (to cover) Protective 1 we expected and found repetition of words taking several rhe- torical and grammatical forms, among them polyptoton, i.e. inflection, declension, and conjugation of a stem; paregmenon, i.e. repetition of words derived from the same etymological root; homonymy, i.e. repetition of words with the same sound and/or spelling but with different meaning; and finally, compounding, i.e. repetition of a word through combination with one or more other words. Our second proposition was that these forms of repetition would be extensive. Specifically, we argued that the repetition would present in a large majority of the screenplay’s scenes. This prediction was strongly supported, as evidenced by the fact that at least one derivative and as many as twenty-one de- rivatives were found in every one on the screenplay’s 174 sce- nes. The final proposition concerned the frequency of the afore- mentioned repetition of theme-associated words. As in with the preceding two, this prediction was also very strongly supported. In particular we found that the observed frequency of deriva- tives associated with themes was far in excess of the expected frequency. We this comparison was made according to theme, we found the observed frequency of derivatives exceeding the expected frequency by as little as 38% to over 900%. Interest- ingly, derivatives associated with the theme “insight” appeared the most frequently—some 388 times in the screenplay—and were found in the greatest number of scenes—123 of 174. This suggests that though this move is ostensibly about a crime scene clean-up business, our results suggest it is really about insight, about developing the capacity to discern the true and inner causes of a situation. To the best of our knowledge, ours is the first study of screenplays to close text analysis and techniques from corpus linguistics to the study of a screenplay. We also believe that the results that arise from these methods of analysis are unique of among studies of the narrative and structure of screenplays. More importantly, we think that these results can make impor- tant and unique contributions to the extant literature on screen- writing theory and practice. The most important of these may be for character development and its link to the plot. At the risk of oversimplifying, we note in the screenwriting literature a Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 17  S. HUNTER, S. SMITH Figure 2. Frequency distribution of derivatives by stem and theme. strong distinction between structure and plot-driven (e.g. Field, 2005) and character-driven (e.g. Viders et al., 2006) approaches. There are dozens of books promoting each approach, few if any of which integrate them. And while we can affect no such rec- onciliation here, we note that the same roots and derivatives that pervade Sunshine Cleaning, that underlie the thematic pat- terns and character arcs, are also used to describe the characters themselves. Our future research will more deeply investigate the etymological roots of character, as well as the relationship between the repetition of roots and derivatives, character, and narrative structure. As we proceed we intend to remain cognizant of the limita- tions of this study and this approach. In this study we applied techniques of computational linguistics to the study of a con- temporary screenplay. Although we can point to measures like word counts, our approach involves a mixture of qualitative and quantitative methods—methods that we think complement each other well. That is to say, together they produced results that would not be possible if employed independent. That said, there is considerable element of choice in our approach which tilts the balance decidedly in favor of the qualitative or subjective element. The words and their etymologies are relatively fixed, but our decision to employ synonyms of key words, as well as roots with synonymous definitions, means that the results here are not completely replicable. That having been said, the gen- eral approach we adopted can surely be used on other screen- plays. For example, consider how the methods described here could be applied to The Hurt Locker, the Academy Award winner for best original screenplay and best motion picture in 2010. Following the analysis of Sunshine Cleaning, we would find the etymological roots of “hurt” and “locker” as well as those of their close synonyms. From there we would examine the screenplay for the presence of other derivatives of those roots. At some point along the way dominant themes would emerge and the grouping of the repeated words by theme would occur. Relationships among the title words (or their stems) would then be examined for evidence of thematic-patterning. Such an analysis might again direct our gaze upon the unstated premise, the primary theme of the story. Obviously, the title would not be the place to begin if applying this method to movies with unusual titles like Thelma and Louise, Alfie, Rambo, or Forest Gump. However, in the former example the word “outlaw” might serve the same purpose. Regardless of the starting point, it is clear that our method rises and falls on the analysis of etymological roots or word histories. Given that that “history” and “story” descend from the same root, weid-, which means “to see”, perhaps we should not be surprised at what this approach reveals about this largely invisible as p e c t of nar r a ti v e . Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank E. Anna Claydon, Jesse Stommel, Donald McCorkindale, Debra Call, Liahna Arm- strong, and other participants of the 2010 Rocky Mountain Modern Language Association conference for their many in- sightful and supportive comments on an earlier draft of this manuscript. REFERENCES Andrew, J. D. (1971). The values of close analysis. Cinema Journal, 11, 48-52. doi:10.2307/1225348 Auerbach, J. (2000). Chasing film narrative: Repetition, recursion, and the body in early cinem a. Critical Inquiry, 26, 798-820. doi:10.1086/448992 Axelrod, M., & Gomez de Garcia, J. (2007). Repetition in Apachean narrative discourse: From discourse structure to language learning in morphologically complex languages. Language, Meaning and Soci- ety, 1, 107-142. Bellour, R. (1979). Cine-repetitions. Screen, 20, 65-72. doi:10.1093/screen/20.2.65 Bordwell, D., & Thompson, K. (2008). Film art: An introduction. New York: McGraw-Hill Higher Education. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 18  S. HUNTER, S. SMITH Botvin, G., & Sutton-Smith, B. (1977). The development of structural complexity in children’s fantasy narratives. Developmental Psychol- ogy, 13, 377-388. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.13.4.377 Briefel, A. (2009). What some ghosts don’t know: Spectral incogni- zance and the horror film. Narrative, 17, 95-110. Brody, J. (1986). Repetition as a rhetorical and conversational device in Tojolabal (Mayan). International Journal of American Linguistics, 52, 255-274. doi:10.1086/466022 Browne, N. (1975). The spectator-in-the-text: The rhetoric of stage- coach. Film Quarterly, 29, 26-38. doi:10.2307/1211746 Bullinger, E. (2003). Figures of speech used in the Bible: Explained and illustrated. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books. Capel, J. (1994). Matthew’s narrative web: Over, and over, and over again. Sheffield, UK: Sheffield Academic Press. Culbert, T. (1963). Narrative technique in Beowulf. Neophilologus, 47, 50-61. doi:10.1007/BF01514944 Cunningham, K. (2008). The soul of screenwriting: On writing, dra- matic truth, and knowing yourself. New York: C ontinuum. Davies, M. (2009). The 385+ million word corpus of contemporary American English (1990-present). International Journal of Corpus Linguistics, 14, 159-190. doi:10.1075/ijcl.14.2.02dav Davies, M. (2012). Cor pu s of American contemporary Eng lish. http://www.americancorpus.org/ Dethridge, L. (2003). Writing your screenplay. Crows Nest, Australia: Allen & Unwin. Doherty, T. (2007). Hollywood’s censor: Joseph I. Breen & the Pro- duction Code Administration. New York: Columbia University Press. El-Shamy, H. (1996). Review: Story-telling techniques in The Arabian Nights by David Pinault. Asian Folklore Studies, 55, 186-189. doi:10.2307/1178883 Fahy, T. (2000). Iteration as a form of narrative control in Gertrude Stein’s The Good Anna. Style, 34, 25-35. Field, S. (1998). The screenwriter’s problem solver. New York: Dell Publishing. Field, S. (2005). Screenplay: The foundations of screenwriting. New York: Delta. Grindon, L. (1996). Body and soul: The structure of meaning in the boxing film genre. Cinema Journal, 35, 54-69. Harper, D. (2012). Online etymological dictionary. http://www.etymonline.com/ Higgins, S. (2008). Suspenseful situations: Melodramatic narrative and the contemporary action film. Cinema Journal, 47, 74-96. doi:10.1353/cj.2008.0010 Holley, M. (2007). Sunshine cleaning. http://www.imsdb.com/scripts/Sunshine-Cleaning.html Hoover, David (2002). Frequent word sequences and statistical stylis- tics. Literary and Linguistic Computing, 17, 157-180. doi:10.1093/llc/17.2.157 Horton, A. (2000). Writing the character-centered screenplay, updated and expanded edition. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. Lacassin, F. (1972). The comic strip and film language. Film Quarterly, 26, 11-23. doi:10.2307/1211407 Langford, B. (2005). Film genre: Hollywood and beyond. Edinburgh: Edinburgh Universi ty Press. The Literary Encyclopedia Concise Glossary (2012). http://www.litencyc.com/glossary_search.php?term=theme&Submit =Search Lord, A. (1960). The singer of tales. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univer- sity Press. Luthi, M. (1982). The European folktale: Form and nature. Blooming- ton, IN: Indiana University Press. Mehring, M. (1990). Screenplay: The blend of film form and content. Boston, MA: Focal Press. Moore, L., & Davis, B. (2002). Quilting narrative: Using repetition techniques to help elderly communicators. Geriatric Nursing, 23, 262-266. doi:10.1067/mgn.2002.128786 Naddaff, S. (1991). Magic time: The movement and meaning of narra- tive repetition. In S. Naddaff (Ed.), Arabesque: Narrative structure and the aesthetics of repetition in the 1001 nights (pp. 89-108). Evanston: Northwestern University Press. Nochimson, M. (1997). Amnesia “R” us: The retold melodrama, soap opera, and the representation of reality. Film Quarterly, 50, 27-38. doi:10.2307/1213614 Norman, M. (2007). What happens next: A history of American screenwriting. New York: Random House. Parker, P. (2002). The art and science of screenwriting. Bristol, UK: Intellect Books. Pinault, D. (1992). An Introduction to the Arabian nights. In D. Pinault (Ed.), Story-telling techniques in the Arabian nights (pp. 16-30). Leiden, Netherlands: E.J. Brill. Reich, A. (2006). The narrative functions of repetition in John Milton’s Paradise Regained. Lewiston, NY: Mellen Press. Robson, K. (1983). The crystal formation: Narrative structure in Grey Gardens. Cinema Journal, 22, 42-53. doi:10.2307/1225218 Sadkin, D. (1974). Theme and structure: The last tango untangled. Literature/Film Quarterly, 2, 162-173. Seger, L. (2010). Making a good script great. Beverly Hills, CA: Sil- man-James Press. Seydou, C. (1983). A few reflections on narrative structures of epic texts: A case example of Bambara and Fulani epics. Research in Af- rican Literature, 14, 312-331. Shostak, D. (1995). Plot as repetition: John Irving’s narrative experi- ments. Critique, 37, 51-70. doi:10.1080/00111619.1995.9936480 Smith, S. (2008). Lip and love: Subversive repetition in the pastiche films of tra cey Moffatt. Screen, 49, 209- 215. doi:10.1093/screen/hjn031 Somsonge, B. (1992). Kui narrative repetition. Mon-Khmer Studies, 22, 149-162. Sprague, C. (1987). Rereading Doris Lessing: Narrative patterns of doubling and repetition. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Caro- lina Press. Suleiman, S. (1983). Authoritarian fictions: The ideological novel as a literary genre. New York: Columbia University Press. Toolan, M. (2008). Narrative progression in the short story: First steps in corpus stylistic approach. Narrative, 16, 105-120. doi:10.1353/nar.0.0000 Turner, J. (1977). Little big man, the novel and the film: A study of narrative structure. Literature/Film Quarterly, 5, 154-163. Viders, S., Storey, G. C., & Martinez, B. (2006). 10 steps to creating memorable characters. New York: Lone Eagle. Walsh, J. (2001). Style and structure in Biblical Hebrew narrative. Collegeville, MN: The Liturgical Press. Watkins, C. (2000). The American heritage dictionary of Indo-Euro- pean roots. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Yemenici, A. (2002). Categories and functions of repetition in Turkish oral narratives. Boğaziçi University Journal of Education, 19, 13-35. Yen, A. (1973). On Vladimir Propp and Albert B. Lord: Their theo- retical differences. Journal of American Folklore, 86, 161-166. doi:10.2307/539749 Yen, A. (1974). Thematic-patterns in Japanese folktales: A search for meanings. Asian Folklore Studies, 33, 2-19. doi:10.2307/1177548 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 19

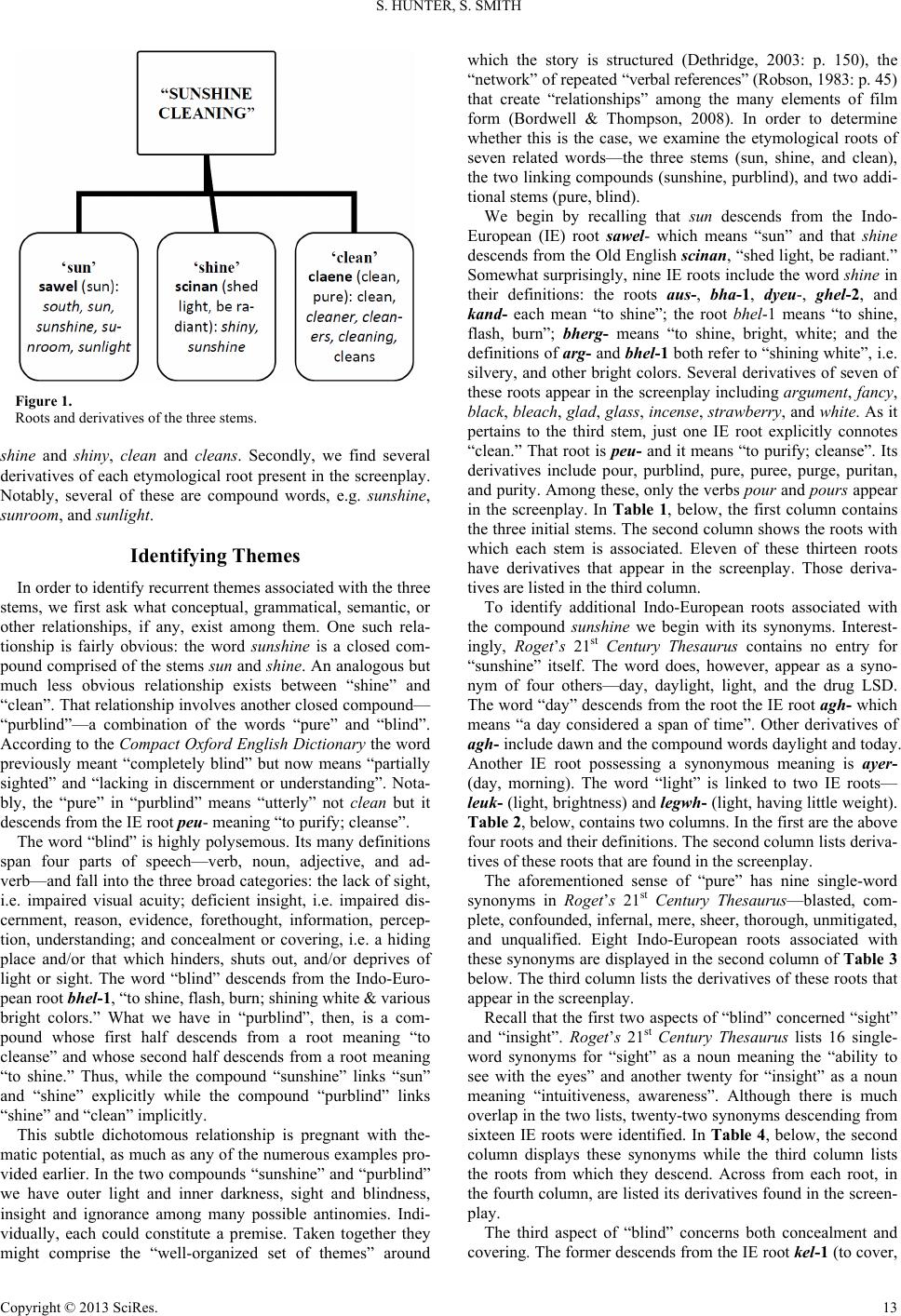

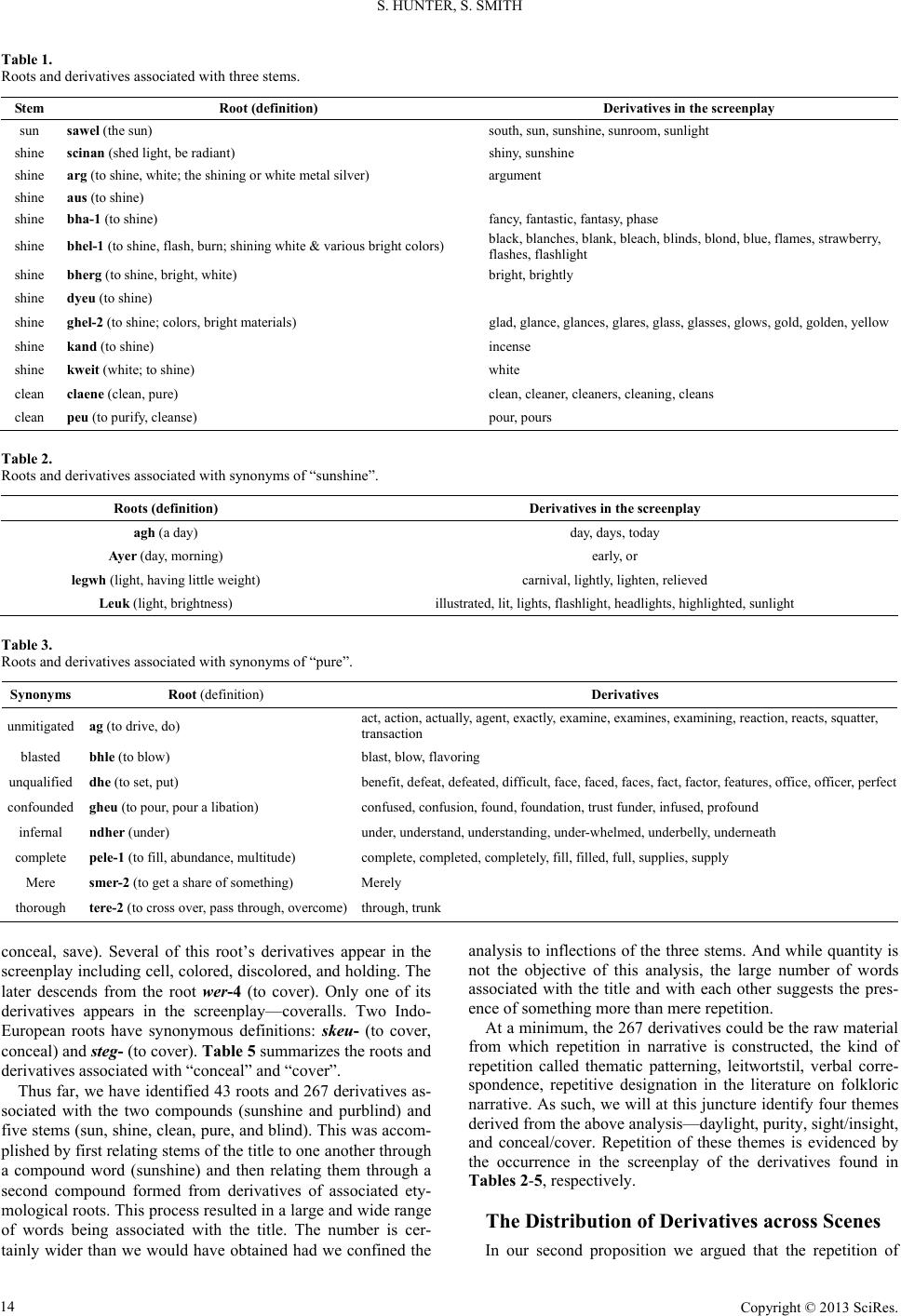

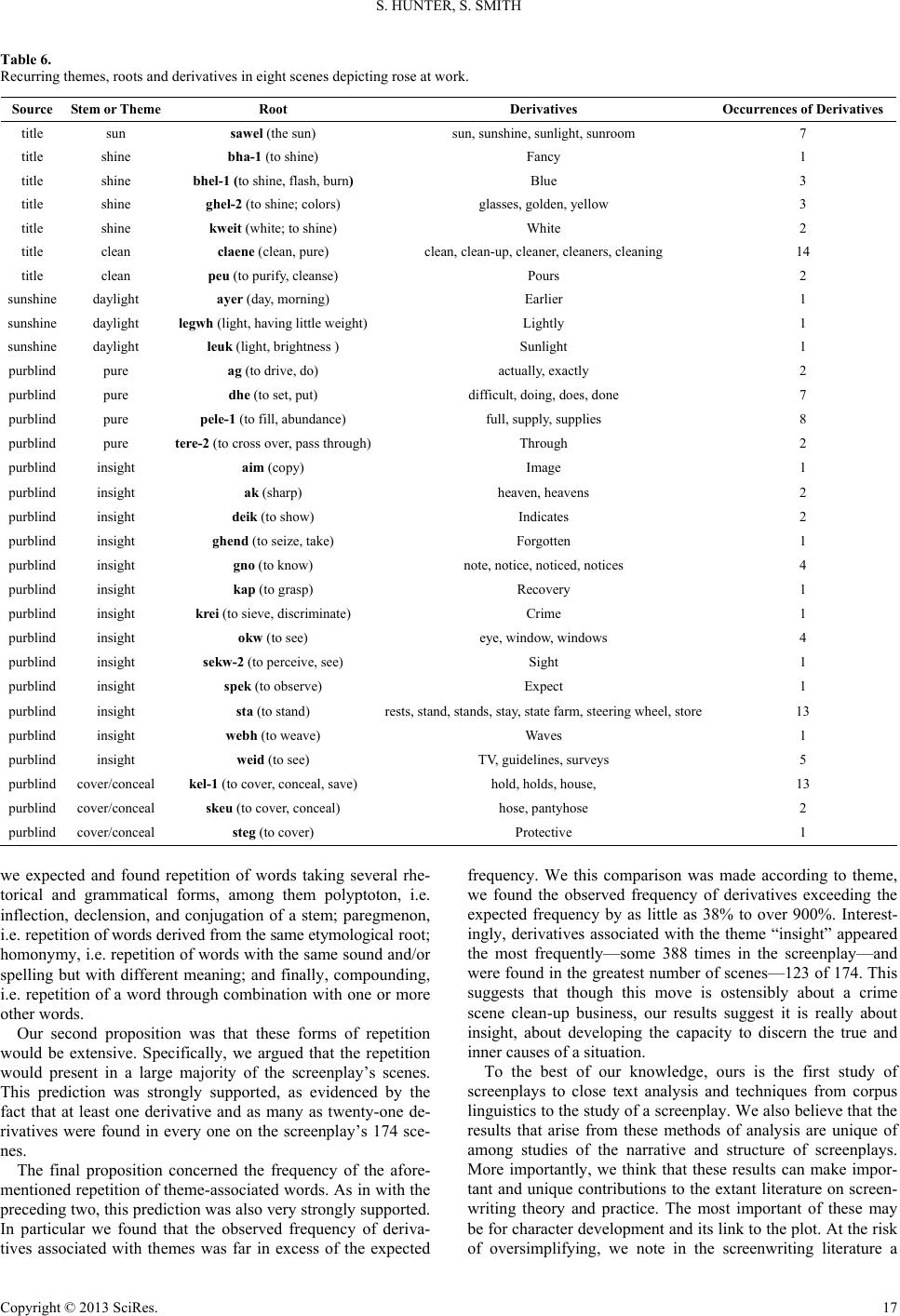

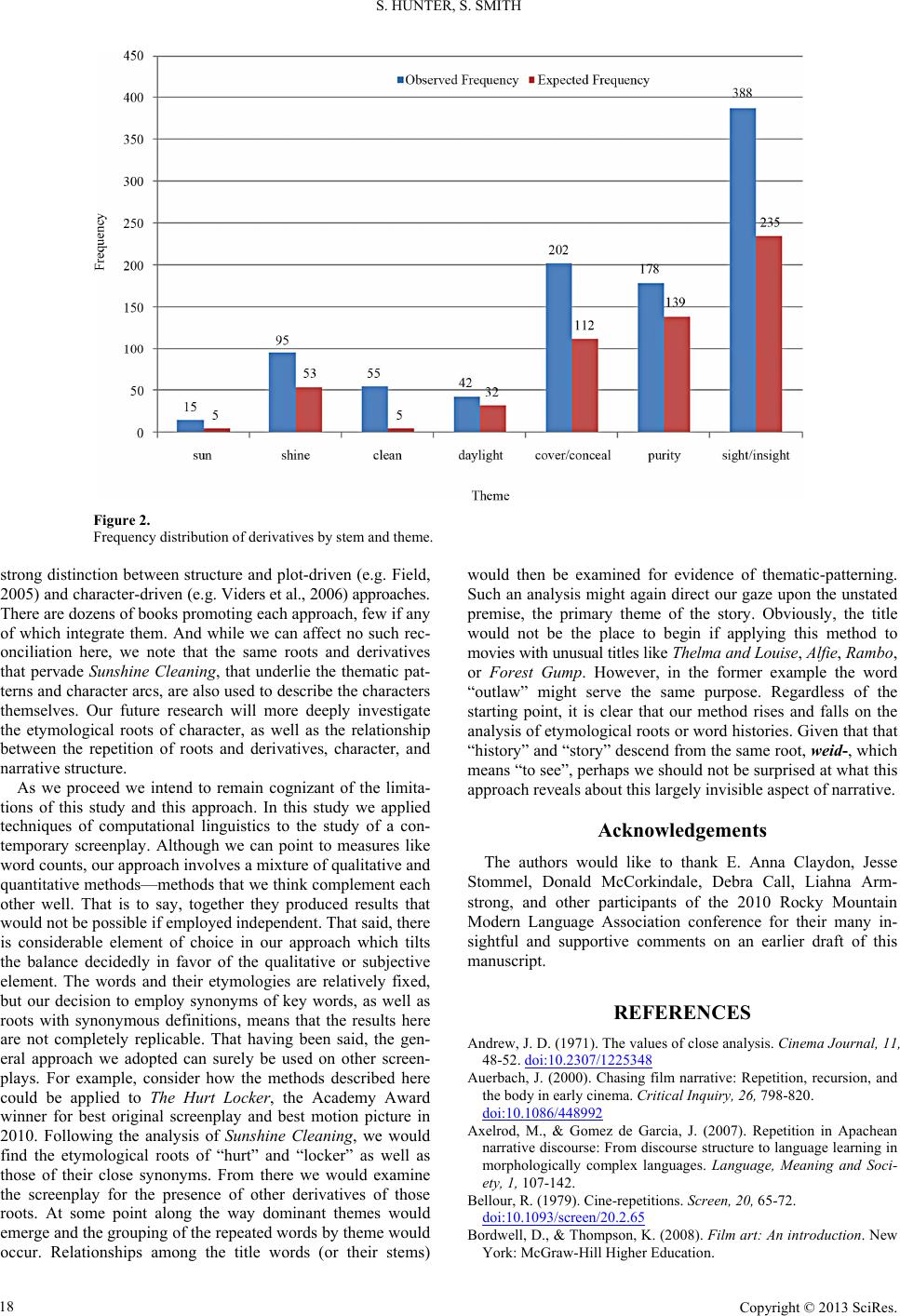

|