Creative Education 2012. Vol.3, No.8, 1311-1319 Published Online December 2012 in SciRes (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/ce) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ce.2012.38192 Copyright © 2012 SciRe s . 1311 The Evolution of Curriculum Development in the Context of Increasing Social and Environmental Complexity Richard Plate Department of Forest Resources and Conservation, University of Florida, Gainesville, USA Email: richarp@ufl.edu Received October 2nd, 2012; revised November 4th, 2012; accepted November 18th, 2012 The history of curriculum development has been characterized and a series of “crises” with the pendulum shifting between traditionalists’ call for getting back to the basics and the progressives’ focus on the learner. However, tracing this history, one can see a common theme in the criticisms expressed by both parties: the failure of the existing curriculum to meet the demands presented by an increasingly complex society. I follow this theme in order to provide historical context for contemporary calls by scientists and educators for wider use of systems-oriented curricula (i.e. curricula designed to improve systems thinking) at primary, secondary, and tertiary levels of education. With this context, one can view these current calls not as a radical shift of direction, but as a logical next stage in the evolution of curriculum. I conclude with a call for more research assessing the effectiveness of systems-oriented instruction and provide guidelines for enhancing the usefulness of such research in the current United States system. Keywords: History of Curriculum Development; Systems Thinking; Complexity Introduction One can hardly believe there has been a revolution in all history so rapid, so extensive, so complete. Through it the face of the earth is making over, even as to its physical forms; political boundaries are wiped out and moved about, as if they were indeed only lines on a paper map; population is hurriedly gathered into cities from the ends of the earth; habits of living are altered with startling abruptness and thoroughness; the search for the truths of nature is infinitely stimulated and facilitated, and their ap- plication to life made not only practicable, but comer- cially necessary (John Dewey). In his 2006 State of the Union address, George W. Bush an- nounced his new educational program, the American Competi- tiveness Initiative, committing over $136 billion over the next ten years “to encourage innovation throughout our economy” (Bush, 2006). A US Department of Education (D.O.E.) report, titled Meeting the Challenge of a Changing World: Strengthen- ing Education for the 21st Century, explains the administra- tion’s view of “innovation”: To Americans, innovation means much more than the lat- est gadget. It means creating a more productive, prosper- ous, mobile and healthy society. Innovation fuels our way of life and improves our quality of life. And its wellspring is education. (US D.O.E., 2006: p. 3) Educator David W. Orr has sharply criticizes Americans’ view of innovation, what he calls “technological fundamental- ism”—a “kind of technological immune deficiency syndrome that renders us vulnerable to whatever can be done and too weak to question what it is that we should do” (2002: p. 63). Nonetheless, Orr would likely find much to agree with in the above characterization, for he aims his criticisms specifically at Americans’ focus on the latest gadget and the general disregard for a more healthy society. In Orr’s words, Americans favor “innovations that produce fast wealth, whatever their ecological or human effects... on long-term prosperity” and neglect inno- vations “having to do with human survival” (2002: p. 69). Both Bush and Orr cite the need for education to respond to the changing global situation. The difference is a matter of focus. For the current Bush administration, a more productive, prosperous, and healthy society implies the need to graduate students who are prepared to compete in a global market and maintain a high level of national security. While Orr acknowl- edges the importance of enabling individuals “to compete more favorably in the global economy”, he suggests that there are “better reasons to rethink education” (1994: p. 26)—among them, the challenges of stabilizing world population, reducing greenhouse gas emissions, protecting biodiversity, and manag- ing renewable resources sustainably. In short, Orr explains, students today “must begin the great work of repairing as much as possible, the damage done to the earth in the past 200 years of industrialization” (1994: p. 26). For Bush, a renewed focus in science and math represents the best way to meet current educational challenges; for Orr, the most important curriculum change involves using environ- mental lessons to integrate school subjects, turning them into a cohesive whole and producing ecologically literate graduates. With these suggestions, both Bush and Orr echo a charge made often during the history of curriculum development in the USA: our schools do not adequately prepare their students to meet the demands of contemporary society. Reasons cited for this failure can be put into two broad categories. One, a critic may find the educational theory to be lacking. That is, new research on edu- cation or cognitive development may have produced findings that point toward new developments in curriculum. And two, the educational context—that is, the demands placed upon stu- dents by society—may have changed, necessitating a corre- sponding change in curriculum. These categories are not mutu-  R. PLATE ally exclusive. In practice critics of curriculum often cite some combination of the two. The focus of this article favors the second category. My ar- gument is not that conventional curricula used at primary, sec- ondary, and tertiary levels of education are fundamentally wrong. Rather, I believe, along with Bush and Orr, that conven- tional curriculum does not prepare students for the new chal- lenges they will face as a result of industrialization and, more recently, globalization. In this article I review how the needs of both the individual and the society have shifted over the last century and trace the response to these shifts in curriculum development. A brief note on terminology is in order. The field of curricu- lum development has come to mean something significantly different from its original meaning. In the seminal text The Curriculum Franklin Bobbitt offers two definitions for curricu- lum: “1) it is the entire range of experience, both undirected and directed, concerned in unfolding the abilities of the individual; or 2) it is the series of consciously directed training experiences that the schools use for completing and perfecting the unfold- ment” (1918: 43, quoted in Jackson, 1992: p. 7). Bobbitt ex- plains, “Our profession uses the term usually in the latter sense” (1918: p. 43, quoted in Jackson, 1992: p. 7). More recently, the field of curriculum development (or simply curriculum) has been broadened to include investigations into the former defini- tion, focusing on the “hidden curriculum” (i.e. implicit lessons that students receive during their educational experience). Thus contemporary studies in the curriculum often analyze the school experience in terms of gender, race, or politics, just to name a few. While this is a rich area of research, I will confine the present discussion to the latter definition, staying, as Phillip Jackson describes “within the single tradition of curriculum specialist as advice giver to practitioners” (1992: p. 27). Efforts regarding this more narrow view of curriculum de- velopment have been criticized for lacking historical perspec- tive (Bellack, 1969; Davis, 1976; Moore et al., 1997). Veteran educators, having over the course of their careers seen countless educational fads move in and out of fashion, have perhaps earned the skepticism with which they often view new educa- tional techniques and tools. As one contemporary educational theorist admits in the introduction of his text on a new theory, “The promise of a new educational theory… has the magnetism of a newspaper headline like ‘Small Earthquake in Chile: Few Hurt’” (Egan, 1997: p. 2). Fortunately, I am not trying to intro- duce a new educational theory here. My objective is much more humble: to point out a specific shortcoming common in con- temporary curricula in our public schools and universities and to suggest systems-oriented instruction as a promising tool for correcting that shortcoming. In the following section, I provide a general history of cur- riculum development in the USA since the end of the nine- teenth century. From this context, Section 3 emphasizes spe- cific aspects of curriculum change and describes its relationship with social change. In Section 4, I describe contemporary social challenges and discuss how systems-oriented instruction, as a reasonable next step in the evolution of curriculum, might ad- dress these challenges. A Short History of Crises in US Education In The Saber-Toothed Curriculum Harold Benjamin (1939) tells the story of a Paleolithic educational system. In this par- ticular tribe schools focused on three skills that were crucial for their young people to learn: fish-grabbing, horse-clubbing, and tiger-scaring. The first skill provided food, the second pro- vided both food and skins, and the third was a matter of safety. Under this system, the young people were taught the skills they needed to prosper in the future and to help the entire tribe prosper in the future as well. There is no shortage of reported crises in the history of cur- riculum design in this country. The first came at the turn of the twentieth century. For most of the nineteenth century American educators emphasized the traditional Latin and Greek curricula of the classics. The field of faculty psychology (also called mental discipline) provided the scientific foundation for these traditional curricula. Proponents of faculty psychology viewed the mind as a muscle to be exercised by memorization and recitation (Pinar et al., 1995: pp. 71-73). Often cited by cur- riculum history scholars, The Yale Report on the Defense of the Classics expresses the motivation behind much of the tradi- tional curriculum: “Familiarity with the Greek and Roman writers is especially adapted to form the taste, and to discipline the mind, both in thought and diction… It must be obvious even to the most cursory observer, that the classics afford mate- rials to exercise talent of every degree” (Yale Report, 1828: pp. 35-36). Nineteenth century critics voiced their objection to the tradi- tional curriculum on two fronts. First, the choice of curriculum was cited as evidence of an over-emphasis by public high schools on college preparation. At its outset American public education was designed to give all of its citizens an equal op- portunity to education. The traditional curriculum, critics charg ed, failed to address the needs of students not bound for college—a group that in the 1889-1890 school year comprised 85% of American high school students (Meyer, 1967: p. 405, Tanner & Tanner, 1990: p. 68). This problem worsened as enrollment in city schools skyrocketed due to large waves of immigrants and the general trend toward urbanization (Cremin, 1961: p. 20; Ornstein & Levin, 2000: p. 152). School was no longer just for the elite; it was for the masses. As such, it was subject to criti- cisms of practicability. Secondly, the focus on memorization and recitation was seen as responsible for shortcomings in students’ basic reasoning skills. As a result, Americans were seen as particularly suscep- tible to persuasive rhetoric. Charles Eliot, the president of Har- vard at the turn of the century and a leading curriculum scholar, argued that the traditional curriculum would not “protect a man or woman…from succumbing to the first plausible deduction or sophism he or she may encounter” (Eliot, 1892: pp. 75-76). He continued, “One is fortified against the acceptance of unrea- sonable propositions only by skill in determining facts through observation and experience, by practice in composing facts or groups of facts, and by the unvarying habit of questioning and verifying allegations” (Eliot, 1892: pp. 75-76). Other leading scholars of the period expressed fear that most Americans were being educated by the “cheap newspapers” that were shaping public opinion “via the emotional appeal of sensational events” (Tanner & Tanner, 1990: p. 91)1. By the turn of the century the work of Edward L. Thorndike, who is credited with the rise of experimental psychology in education, had discredited faculty psychology, taking away the traditionalists’ scientific foundation (Cremin, 1961; Pinar et al., 1995). However, Tanner and Tanner (1990) suggest that a more 1See also Cremin (1971). Copyright © 2012 SciRe s. 1312  R. PLATE powerful force of change was at work as well. They explain that the traditional curriculum, as well as faculty psychology, “had originally evolved to serve an aristocratic society and, in addition to being absolutely unfounded from a scientific stand- point, it did not meet the new social and industrial demands of a democratic society. These demands, rather than the findings of experimental psychology, proved to be the most powerful ar- gument against mental discipline” (1990: p. 110). As a result of this failure, in 1900 the vast majority of students (almost 90%) enrolled in public schools dropped out before graduating high school, citing a lack of need for what was being taught (Tanner & Tanner, 1990: p. 72)2. The result of the criticism and public dissatisfaction was a broadening of the curriculum and a shift of emphasis toward the learner. Classical studies gave way to contemporary and voca- tional studies, and it was in this context, during the first few decades of the twentieth century, that John Dewey’s progres- sive ideas of education came to exert more influence on cur- riculum. The focus shifted from classical materials and lan- guages to meeting the individualized needs of the student. This shift is evidenced in catch phrases like “the needs of learners,” “teaching children, not subjects,” and “adjusting the school to the child” (Cremin, 1961: p. 328). In addition to bringing the learner into focus, this period also saw a new emphasis on the connection between education and the welfare of society as a whole. More specifically, Lester Frank Ward—and later Dewey—proclaimed the potential for a school system to create social change (Pinar et al., 1995: p. 104). Many educational reformists believed that the industriali- zation of society not only created a demand for a skilled public, but also “had dissolved the fabric of community leaving alien- ation in its wake” (Cremin, 1961: p. 60). In this context the role of school broadened to include preparing students not only for a career, but also for understanding their career in the context of the larger social system3. A statement from the oft-cited 1917 National Education Association (NEA) report, “The Cardinal Principles of Secondary Education,” illustrates how the inclu- sion of both the individual student and the larger connections to society had become part of the institutionalized focus of educa- tion: “Education in a democracy…should develop in each indi- vidual the knowledge, interests, ideals, habits, and powers whereby he will find his place and use that place to shape both himself and society toward ever nobler ends” (1918: p. 157). This shift of focus met with its own set of critics who be- lieved that the progressive influence was making education soft, ultimately depriving students of a sound background in basic lessons. Such criticism came to a head after the end of World War II, energized by new concerns regarding communist ex- pansion and the rise of the Soviet Union. These concerns com- bined with budgeting problems brought about by the war, ram- pant inflation, and ever-increasing industrial demands for a trained, intelligent workforce to usher in “the deepest educa- tional crisis in the nation’s history” (Cremin, 1961: p. 339). Numerous texts, including Bernard Iddings Bell’s Crisis in Education (1949) and Arthur Bestor’s Educational Wastelands (1953), accused education of misplaced emphasis on social and emotional matters to the detriment of fundamental, academic skills. Curriculum scholar Hilda Taba suggested, “Public edu- cation today is facing a crisis which may be deeper and more fundamental than any preceding one” (1962: p. 1). The launch of the Soviet satellite Sputnik in 1957 galvanized concerns regarding Soviet supremacy over the USA, reinforc- ing the back-to-the-basics attitude in school and placing science education at the center of concern. Congress responded with the National Defense Education Act (NDEA) in 1958, directing federal funding to improve science and mathematics curricula and increase opportunities for exceptional students seeking training in critical scientific fields4. The National Academy of Sciences organized a conference at Woods Hole in Cape Cod, gathering together leading psychologists, scientists, and mathe- maticians to discuss how best to help American students be- come the scientific leaders of the future. Jerome Bruner, chair of the conference, published the results in the physically unas- suming book, The Process of Education (1953). Weighing in at ninety-two pages, The Process of Education is widely viewed as the most influential curriculum text of its time (Tanner & Tanner, 1980; Willis et al., 1993; Pinar et al., 1995; Marshal et al., 2000), during a period referred to as “one of the largest and most sustained educational reform move- ments in American history” (Silberman, 1970: p. 158). Bruner devoted the opening two chapters to the importance of teaching the “structure of the disciplines,” meaning basic concepts re- garding each subject (e.g. chemistry, language, mathematics). This phrase—and indeed the whole text—was understood by back-to-the-basics proponents as supporting the need for a rig- idly defined discipline-centered curriculum. Richard Hofstadter (1963) even stretched Bruner’s ideas to support Hofstadter’s own arguments for a resurgence of faculty psychology. While Bruner’s ideas are at times overly rigid5, Marshal et al. point out, “To be fair, Bruner’s ideas were far more complex than the manner in which they were eventually employed” (2000: p. 57). We will revisit the complexity of Bruner’s ideas later in the article. For all of its influence, Bruner’s strict, top-down system of curriculum development did not match the 1960s trend toward liberation. By 1969, educators had come to associate the top- down curriculum with “the military-industrial complex, patri- archal hierarchies, heterosexual orthodoxies and conventional wisdom,” (Marshal, 2000: p. 92), to which they had become resistant. As a result, they pushed for a more responsive cur- riculum, giving rise to what Pinar et al. characterize as a “crisis of meaning” (1995: p. 188). Charles Silberman’s (1970) widely read indictment of education Crisis in the Classroom helped to usher in a new stage of curriculum development—humanistic reform. Silberman argued that “schools can be genuinely con- cerned with gaiety and joy and individual growth and fulfil- 3In Democracy and Social Ethics, Jane Addams provides many examples o how the industrial work could be humanized by providing future workers with a broader perspective of the system. For example, she explains, “It takes thirty-nine people to make a coat in a modern tailoring establishment, yet those same thirty-nine people might produce a coat in a spirit of ‘team work’ whi ch would make th e entire proces s as much mor e exhil arating than the work of the old solitary tailor” ( 1902: p. 219). 4The current Bush administration cites the success of this program as a model for the A merican Competitiveness Initia tive (US D.O.E., 2006: p. 4). 5In addit ion to being ass oci ated wit h a back -t o-t he- asics movement, Bruner is also criticized for removing the curriculum specialist and teacher from the rocess of curriculum development. The almost total absence of teachers and curriculum specialists at the Woods Hole conference lends credence to this critici s m. 2Kliebard (1995) reports of a 1913 survey of child laborers in Chicago. Helen M. Tood, a factory inspector asked 500 children working in the facto- ries if they would prefer to be in school if their families could afford it. Kliebard explains, “Of the 500,412 told her, sometimes in graphic terms, that they preferred the often-grueling factory labor to the monotony, hu- miliation, and even sheer cruelty that they experienced in school” (6). Copyright © 2012 SciRe s . 1313  R. PLATE ment without sacrificing concern for intellectual discipline and development” (1970: p. 208). It was in this context that the Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development enti- tled their 1970 yearbook To Nurture Humaneness and devoted it to how to remain humane in the midst of the broad social changes that were taking place. In one chapter of the yearbook, Francis S. Chase identifies several types of knowledge needed in order to develop “in the individual those capabilities believed to be distinctively human,” including “knowledge of self,” “knowledge of others,” and “knowledge of the evolution and functioning of institutions” (pp. 98-100). Other curriculum texts of the period (e.g. Weinsten and Fantini’s (1971) Toward Hu- manistic Education)—exhibit a similar focus on personalizing the curriculum, teaching students to retain their sense of hu- manity despite the pressures of modern society. But this focus on humaneness did not last for long. By the 1980s the USA’s global economic dominance was diminishing, and just as critics of the 1950s blamed lack of educational rigor for the USA falling behind in the space race, 1980s critics cited lack of educational rigor for the USA’s waning economic po- wer. In 1983 the National Commission on Excellence in Educa- tion, appointed by the Reagan administration, published A Na- tion at Risk, accusing educators of “losing sight of the basic purpose of education” and squandering “the gains in student achievement made in the wake of the Sputnik challenge” (Na- tional Commission on Excellence in Education 1983: p. 1)6. Authors of the report call for a return to the core subjects that had been neglected as a result of schools attempting to provide “solutions to personal, social, and political problems” (National Commission on Excellence in Education, 1983: p. 1). While many have since challenged the evidence used (Ber- liner & Bingman, 1997) or the conclusions drawn (e.g. Willis et al., 1993; US Department of Education, 1986) in A Nation at Risk, no one denies its broad impact on schools and curriculum. First, it served to widen the gap between the field of curriculum and the development of “consciously directed training experi- ences.”7 Second, it brought ideas like educational assessment and school/teacher accountability to the center of the conversa- tion about US schools. These topics have retained their central position through to the present, but while many decry the cur- rent focus on standardized tests as the sine qua non of educa- tional assessment, contemporary texts on curriculum develop- ment still include a combination of progressive and traditional themes. For example, Arthur K. Ellis divides Exemplars of Education (2004) into chapters on “Learner-Centered Curricu- lum,” “Society-Centered Curriculum,” and “Knowledge-Cen- tered Curriculum,” echoing the historical themes of curriculum development. In the next section, I will identify an additional theme—the co-adaptive curriculum—in order to place systems- oriented instruction within the history just discussed. The Co-Adaptive Curriculum With the Paleolithic educational system conveying the three most important skills—fishgrabbing-with-bare-hands, woolly- horse-clubbing, and tiger-scaring-with-fire—the tribe pros- pered for many years with “fish or meat for food,” “hides for clothing,” and “security from the hairy death.” Benjamin ex- plains, “It is to be supposed that all would have gone well for- ever with this good educational system if conditions of life in that community had remained the same forever” (1939: p. 33). However, the tribe did so well that after generations of fish- grabbing, the slow fish available for grabbing had all been eaten, leaving only the faster, more alert fish. And after gen- erations of horse-clubbing, the small woolly horses available for clubbing had left and been replaced by shy and speedy an- telopes that could smell attackers long before they were within a club’s reach. The saber-toothed tigers had become extinct (due to reasons unrelated to the scaring itself) and were re- placed by bears that were not as easily repe lle d with fire as the tigers were. In The Child and the Curriculum, John Dewey (1902) de- scribes two camps of thought regarding education—those who support a traditional core curriculum and those who support changing the curriculum to better reflect the interests of the child. After describing each of these positions for several pages, Dewey notes, “Such oppositions are rarely carried to their logi- cal conclusion” (1902: p. 15). While Dewey is famous for his ideas regarding educational reform, he recognized that the di- vide between traditionalists and reformists is not absolute. Dewey continues, “Common-sense recoils at the extreme char- acter of each of these results. They are left to the theorists, while common-sense vibrates back and forward in a maze of inconsistent compromise” (1902: p. 15). This understanding should be kept in mind when interpreting the above history of crises. A key theme runs throughout the ebb and flow between progressivism and traditionalism: the attempt to adjust educa- tion to meet the needs of an increasingly complex society. Before tracing the history of this theme in curriculum devel- opment, let us pause for a moment to reflect on what meeting the needs of modern society means. The systems concepts of bi-directional causality and scale may be useful here for under- standing the nature of this challenge. Figure 1 shows a two- by-two matrix, illustrating four distinct aspects of meeting so- II. A. Abilitytounderstand currentsocialneeds B. Abilitytomeet nationaloccupational needs I. A. Personalskillsfor everydaylife B. Skillsfor employability III. A. Abilitytoforge one抯senseof individuality B. Inclinationtoward personal development IV. A. Abilitytoperceive/ respondtofuture socialneeds B. Abilitytoprovide innovativemeansto improvesociety SocietyEducation EducationSociety Individual Social one’s sense of 6George Willis et al. (1993) note a key difference between this and the post-Sputnik efforts of the 1960s: “In that era the federal government began to supply large amounts of funding for schools; in the 1980s, in contrast, the federal government placed responsibility for funding educational reforms on state and local governments while at the same time reducing the overall level of revenues it dis persed to stat es and local communities” (401). 7Recall this term from Bobbit’s duality explained in the opening of this chapter. In the 1970s and 1980s the field of curriculum moved away from lanning the classroom experience and focused instead on understanding aspects of the “hidden” or unofficial curriculum. This scholarship involves deconstruction of the curriculum in order to identify hidden power relation- ships with an eye toward, for example, feminist, racial, and literary theory (e.g. Pinar, 1998; McCarthy & Crichlow, 2005). Figure 1. The co-adaptive relationship between education and society. Copyright © 2012 SciRe s. 1314  R. PLATE ciety’s needs. Quadrants I and II illustrate the how society in- fluences education. On the individual scale, schools are sup- posed to develop in students those skills necessary for em- ployment and for dealing with the challenges of everyday life8. On a social level, this function may translate into a number of educational goals, from meeting community or national occu- pational needs to creating a voting public able to understand the political and social concerns of the day9. In quadrants III and IV the arrow of influence is reversed. In this context, schools are expected to produce students who have the ability to take a proactive role in defining both their own identity within society and redefining society to meet future unforeseen needs. Scholars may argue about where the proper balance lies in meeting these goals, but most would agree that all four are nec- essary to some degree. Quadrants I and II serve immediately practical goals of meeting current individual and social chal- lenges and provide social cohesion, while quadrants III and IV enable society to grow, for each generation to find its own truths within the context of the truths it has learned. I have used the term co-adaptive in describing the curriculum to emphasize this dual nature. Responding to society’s needs does not simply mean molding the individual to fit society; it must also include developing individuals who can help to mold society. Using this model, one can trace the theme of meeting soci- ety’s changing needs through the history of curriculum devel- opment crises. Even in the Yale Report of 1828, the argument for retaining the classic Latin and Greek curricula was ex- pressed as more than a historical appreciation for our cultural heritage. Classic texts were presented as the most useful means of providing students with “the discipline and the furniture of the mind” (Italics in original text: 28)—i.e., providing student with thinking skills such as “the art of fixing the attention, di- recting the train of thought, analyzing a subject proposed for investigation” (p. 28). The focus here was on the development of the individual—quadrants I and III. While the Yale Report might be considered more readily connected to quadrant III (e.g. creating a civilized society as measured by knowledge of clas- sic texts) than to quadrant I, the report’s authors contended that skills acquired in the classic curricula could be generalized and applied to modern challenges. This report has been criticized not for its focus on thinking skills, but for its contention that these skills could be best developed by memorizing passages of classic texts. That is, critics agreed with the central importance of improving students thinking skills, but argued that the classic curricula were almost entirely divorced from the skills required in an industrializing nation of the 1890s. This same criticism lies at the heart of both the turn of the century crisis that resulted in the rise of progressive education and the post WWII crisis that saw the fall of progressivism. Taba characterizes the difference between these two crises, noting that while the “criticisms of the1890s flailed against formalism, hard discipline, [and] narrowness of education,” 1950s critics faulted schools “for their softness, anti-intellectu- alism, progressivism, egalitarianism, [and] a lack of emphasis on fundamentals and academic skills” (1962: p. 2). But she explains that both crises were “caused by the transforming ef- fects of technology and science on society, with criticism fo- cusing on the failure of the schools to solve the problems cre- ated by that transformation” (1962: pp. 1-2). Similarly, Cremin suggests in 1955, “As in the period between 1893 and 1918, new social and intellectual currents are calling for new educa- tional outlooks” (1955: p. 308). Just as traditionalists of the nineteenth century had failed to adapt to contemporary needs, the progressives of the mid-twentieth century “failed to keep pace with the continuing transformation of American society (Cremin, 1961: p. 351). Tanner and Tanner echo this sentiment, citing the progressives’ “inability to recognize social change” (1990: p. 262) as a primary reason for their decline. The NEA’s 1918 report (quoted earlier)10 illustrates how this theme of adjustment to modern needs came to be emphasized on both individual and social scales. The focus on shaping both the individual and society “toward ever nobler ends” demon- strates the inclusion of quadrants III and IV in the NEA’s view of education. Dewey’s writing during this period also empha- sizes the inclusion of the social scale. Indeed, an emphasis on the impact that education can have on social development, as well as on the connections between individual and social wel- fare, stands as a defining contribution of Dewey’s progressive ideas (e.g. Dewey, 1902, 1916). While many scholars empha- size the stark differences between the progressivism before WWII and the return to a more structured core curriculum post- Sputnik, a close evaluation of the dominant texts of the late 1950s shows a continuation of this same theme of individual and social adjustment to meet the challenges arising from a more complex soci ety. Smith, Stanley, and Shores’ (1957) synoptic text Fundamen- tals of Curriculum Development provides a good example, not only because it was highly influential, but because their de- scription of the social challenges of the day appear no less relevant half a century later. Their discussion rests on the premise that “the progress of science and technology has been attended by far-reaching cultural changes, which have created grave social problems” (p. 25). The authors develop this idea with a detailed account of how specialization—“minute divi- sion of labor” (p. 32)—has paradoxically increased both social interdependence and individual isolation—the former because nothing gets produced without a team effort and the latter be- cause “each individual carries around in his head a specialized picture of society, representing but a fragment of the total social pattern” (p. 32). Devoting a little space early on to bemoaning the changes at hand, the authors proceed to describe the need for “a new common sense,” better suited for the realities of the day, and they are clear about the role of education in meeting this need: It is the obligation of those who are responsible for cur- riculum building to provide opportunities for children, young people, and adults to engage in the common task of rebuilding ideas and attitudes so as to make them valid for the purpose of social judgment and action in a period dominated by the complex web of impersonal relations. (pp. 52-53) 8Philosopher Richard Rorty explains, “Even ardent radicals, for all their tal of ‘education for freedom’, secretly hope that the elementary schools will teach the k ids to wai t their turn in lin e, not to s hoot up in the johns , to obey the cop on the corner, and to spell, punctuate, multiply, and divide” (1999: p 117). 9Large scale social norms, such as valuing the tenets of a democratic gov- ernment, might also fit into this quadrant, but would overlap into quadrant IV. 10“Education in a democracy…should develop in each individual the know- ledge, interests, ideals, habits, and powers whereby he will find his place and use that place to shape both himself and society toward ever nobler ends” (Department of the Interior, 1908: p. 157). Copyright © 2012 SciRe s . 1315  R. PLATE The focus here is clearly in quadrant II. And perhaps more importantly, the focus is on item A of this quadrant, a signifi- cant distinction given the charges that curriculum development during this period was focused too narrowly on the USA’s need for future scientists in order to compete technologically with the Soviet Union (i.e. focus on item IIB). Such a characterization is overly simplistic. Even texts fo- cused on the nation’s occupational needs viewed the challenge more broadly. The 1958 Rockefeller Report, Education and the Future of America—after describing social changes similar to those identified by Smith et al. (1957)—emphasizes the need for more future scientists, but the authors explain that the chal- lenge lies not in filling shortages in one or two occupations, but something more inclusive: “It is not a shortage now of engi- neers, now of economists, that lies at the root of the problem. It is the constant pressure of an ever more complex society against the total creative capacity of its people” (Italics in original: 10). The upshot of this constant pressure is clear: “Among the tasks that have increased most frighteningly in complexity is the task of the ordinary citizen who wishes to dis- charge his civic responsibilities intelligent l y” (p. 11). If the curriculum crisis of the 1950s was brought about by the difficulty in understanding the new social complexities of the time, then the 1970s crisis was a matter of retaining a sense of personal connection to others amidst those complexities. The sense of individual isolation described by Smith et al. (1957) had increased, and curriculum scholars sought to address the problem in an affective context. Introducing the 1970 yearbook for the Association for Supervision and Curriculum Develop- ment, Scobey and Graham express their interest in “educating for humaneness during the so-called ‘human revolution,’ the ‘technological revolution,’ and the ‘revolution of expanding knowledge’ now in progress” (1970). Like Smith et al. (1957), contributors to Scobey and Graham (1970) identify widespread changes in society and suggest ways to adjust curriculum to best aid students in meeting new demands brought about by those changes. In terms of the educational needs model in Fig- ure 1, attention shifted from quadrants I and II to quadrant III. But this shift was short-lived. The US Department of Educa- tion’s 1983 report A Nation at Risk quickly steered the discus- sion of educational objectives back to quadrants I and II. Most of the attention received by this report has focused on the enormous influence it had on assessment and accountability in education, but the authors’ expression of the social needs of the time is more pertinent to the current discussion. In the context of quadrant I, the authors explain that in an age of globalization, Americans are not only competing against other Americans, but against a global pool of potential employees and businesses. As a result, “individuals in our society who do not possess the levels of skill, literacy, and training essential to this new era will be effectively disenfranchised” (1983: p. 2). As before, technology fuels this new era, “penetrating every aspect of our lives” and “transforming a host of … occupations” (1983: p. 3). And again, the civic importance of curriculum reform is high- lighted: “For our country to function, citizens must be able to reach some common understandings on complex issues,” at- taining “the mature and informed judgment needed to secure gainful employment, and to manage their own lives, thereby serving not only their own interests but also the progress of so- ciety itself” (1983, pp. 2-3). My contention here is not that these historical texts are all calling for the same thing. Indeed, one could hardly find a pair of texts that differed more than To Nurture Humaneness and A Nation at Risk. The disparity between these texts only strength- ens the point at hand: Historical calls for educational reform, for all of their differences, have shared a focus on adjusting curriculum to meet the increasingly complex demands of an increasingly complex society. In the following section, we will look at our contemporary social needs and how they translate to educational goals. A New Crisis? As a result of the prehistoric changes, the Paleolithic tribe no longer had food, clothes, or security from the hairy death. But in a short time, the Paleolithic tribe’s innovators caught up with the changes of the fish, the antelope, and the bears. Fish- ers learned to net fish rather than grab them, horse-clubbers learned to snare antelope instead of clubbing them, and tiger- scarers learned to dig bear pits instead of using fire. As a result, the tribe had more fish, meat, and skins than they had ever had before. Some suggested that in light of these new conditions the educational curriculum be adjusted to address these new skills. But the majority argued that the curriculum was already filled with fish-grabbing, horse-clubbing, and tiger-scaring, leaving no room for “fads and frills like net-making, antelope-snaring, and—of all things—bear killing” (Benjamin, 1939: p. 43). In light of the history recounted above, one might be hesitant to declare yet another crisis in education. Given the luxury of historical perspective, one can view the series of crises as sim- ply the continuing development of curriculum necessary to meet the changing demands of a changing society. In this con- text, it may be worth surveying some contemporary changes in society. Let us start in quadrant I with occupational demands. Describing the collapse of progressive education after WWII, Cremin explains, “The econo my had entered upo n an era m a rked by the harnessing of vast new sources of energy and the rapid extension of automatic controls in production, a prodigious advance that quickly outmoded earlier notions of vocational education” (1961: p. 351). A recent report from the US De- partment of Education echoes this same shift: “Whether filling “blue collar” or “white collar” positions, employers seek… practical problem-solvers fluent in today’s technology. If cur- rent trends continue, by 2012, over 40 percent of factory jobs will require postsecondary education” (2006: p. 4). In this context, being a practical problem-solver means more than being technologically savvy. In a 1989 article in Fortune Magazine Brian Dumaine, describes a new trend in US industry, explaining that “the most successful corporation of the 1990s will be something called a learning organization, a consum- mately adaptive enterprise with workers freed to think for themselves, to identify problems and opportunities, and to go after them” (p. 48)11. A joint report produced a decade later by the US Departments of Commerce, Education, and Labor sup- ports Dumaine’s assertion, predicting that economic success in the 21st century “will require adopting organizational work sys- tems that allow workers to operate with greater autonomy and accountability” (1999). Table 1, taken from the 1999 report, illustrates the organizational shift from linear hierarchies to flexible networks that will require employees to have a broader understanding of their organization’s operations (US Depart- ments of Commerce, Education, and Labor, 1999: p. 3). Note 11One might cite 3 M as an example of the type of organization Dumaine describes. Copyright © 2012 SciRe s. 1316  R. PLATE Copyright © 2012 SciRe s . 1317 Table 1. Organizational shift in companies and the need for systems thinking skills in employees (from U.S. Department of Commerce, Education, and Labor, 1999). Element Old System New System Workplace organization Hierarchical Rigid Function/specialized Flat Flexible Networks or muti/cross- functional Teams Job design Narrow Do one job Repetitive/simplified Standardized Broad Do many jobs Multiple responsibilitie s Employee skills Specialized Multi/Cross-skilled Workforce management Co mmand/control systems Self-management Communications Top down Need to know Widely diffused Big picture Decision-making responsibility Chain of com mand Decentralized Direction Standard/fixed operating procedures Procedures under constant change Worker autonomy Low High Employee knowledge of organization Narrow Broad that the difference on this table between the Old System and the New System is analogous to the shift called for by proponents of systems-oriented curricula. But today’s students will also face a number of new chal- lenges represented in the social challenges of quadrant II. Re- call that in the history of educational crises, calls for curriculum change were generally made in the context of social change. That is, observations regarding increased complexity referred primarily to changes in relationships between people, often brought about by technological advance. Today, in addition to changing the nature of our relationships with each other, tech- nological advance has also changed our relationship with the environmental systems that support us. Ervin Laszlo alludes to this change in his discussion of the logic of the modern Indus- trialized society—“a logic”, he explains, “that led from the “progressive appropriation of the world” to “progress that mas- ters the world”, all the way to the environmental, economic, social and cultural limits inherent in industrialization” (Laszlo et al., 1993). In other words the complexity inherent in earlier stages of industrialization involved learning to succeed in a world made faster, busier, less personal, and more complicated by increased appropriation of resources, but the resources themselves were believed to be infinite, as was the ability of the earth to deal with the wastes produced through the use of those resources. The complexity cited in the early quotations above still refers to a world without limits. Today, the idea of a “complex soci- ety” has grown to include the limits of a finite world, and as we approach these limits, Laszlo suggests, “the developmental curve of modern industrial society registers a turnaround” (Laszlo et al., 1993). One need not look very hard to observe evidence of this turnaround. For example, the earth currently holds 6.3 billion people, roughly twice the population of the 1960s when human effects on environmental systems first became widely noticed in the USA, and that number is expected to grow to almost 9 billion by 2050 (Cohen, 2003). In addition, the level of con- sumption per capita in industrialized nations has increased. In the USA personal consumption expenditures increased 33% from 1993 to 2004 (Council of Economic Advisors, 2005). Increased human population and consumption has led to in- creased problems managing wastes from human activity. For example, industrial air pollution now poses a serious health risk on both regional and global scales (Akimoto, 2003; Ezzati et al., 2005), and global climate change has now been officially rec- ognized by leading nations, including the USA, as a “serious and long-term challenge” attributed “in large part” to human activities (G8 Gleneagles, 2005). Add to these concerns the loss of biodiversity (Jenkins, 2003), the collapse of large fisheries (Pauly et al., 2003; Essington et al., 2006), the loss of forests and soils (Stocking, 2003; Wright & Muller-Landau, 2006), and the projected scarcity of potable water (Tully, 2000; Gleik 2003), and one might be tempted to look nostalgically back at, say, the 1950s, when an increase in the complexity of society referred only to the dehumanization of the individual as a result of industrialization. Ecologists Howard Odum and Elizabeth Odum (2001) write extensively about this turnaround in the text A Prosperous Way Down. The Odums argue that, as their title suggests, the pros- pect of making the adjustments necessary to address these challenges need not inspire apocalyptic visions of collapse. In their view “the global society can turn down and descend pros- perously, reducing assets, population, and unessential baggage while staying in balance with its environmental life-support system” (2001: p. 3). However, such a path would require sig- nificant changes in social policies and institutions analogous to those outlined in Table 1. Therefore, without belittling the pro- blems of prior generations, it seems fair to say that today’s stu- dents will face a set of challenges qualitatively different than those facing students when Smith et al. wrote: An educational program must include new patterns of thin- king, wherein a number of social variables in politics, economics, and the like are kept in the picture in the process of reaching conclusions about social policies and actions, instead of the prevailing and now obsolete habit of thinking in a linear and compartmentalized fashion (where, for example, the attempt is made to keep political and economic thought in their separate spheres) (1957: p. 95).  R. PLATE We can nevertheless learn from their wisdom, continuing to ask ourselves what new patterns of thinking might best enable us to address contemporary challenges. Conclusion The story of the Paleolithic tribe struggling with its own cur- riculum controversies (e.g. tiger-scaring versus bear-pit-digging) ends with the Paleolithic youths, bored by the obsolete curricu- lum, becoming listless underachievers. Meanwhile, a neighbor- ing tribe—a thinly veiled version of Hitler’s Germany that has taken a more pragmatic position regarding curriculum af- fairs—invades. The story, written in 1939, is in some ways a product of its time, but one need not try very hard to see echoes of it in the stories implied by George W. Bush and David W. Orr at the opening of this article. In Bush’s version, the neighboring tribe would not be Nazi Germany, but perhaps China or India. And the invasion would not be military, but economic. In Orr’s version, the invading tribe would not be people at all, but rather the compounding problems created by our own environmental negligence collapsing upon us. In any case, the point would be the same: a curriculum must evolve with the society for which it is designed. In this article I have reviewed the history of curriculum de- velopment, characterizing it as a series of curriculum changes brought about through co-adaptation with changes in society itself. The practice of adjusting curriculum in order to address the educational needs of an increasingly complex society is nothing new. However, the degree of complexity has grown exponentially with our population and our technological capa- bility to affect large-scale systems (e.g. climate change). In 1861, Herbert Spencer asked a question that has been quoted so often in curriculum texts, one might consider it the north star of the field of curriculum development: “What knowl- edge is of most worth?” (p. 11). We might also take Smith et al. lead and ask, What patterns of thought are of most worth? Many scholars (Boulding, 1953; Meadows, 1991), scientists (Odum, 1994; Forrester, 1996), educators (Orr, 1994; Booth Sweeney & Sterman, 2000), business leaders (Agyris, 1976; Ackoff, 1999), and politicians (Strong, 2001; Gore, 2006) have suggested that systems thinking represents a set of skills par- ticularly well suited for addressing our current challenges. De- spite this fact, systems-oriented instruction remains an under- used and under-studied aspect of curriculum development. There are numerous anecdotal accounts of the usefulness of systems-oriented instruction for improving students’ ability to understand and manage complexity. However, convincing more educators and administrators to explore this avenue will require quantitative data, and any methodology used to acquire that data will likely need to have the following attributes: 1) Short assessment period: Standardized tests are popular, largely beca use they are easy to administe r in large numbers. A number of studies (e.g. Maani & Maharaj, 2004) utilize meth- odologies of assessing systems-oriented instruction that are useful as early explorations, but are too time consuming—for both the researchers and the participants—to be used on a broader scale. Producing the amount of data necessary to draw strong conclusions about the effectiveness of systems-oriented instruction will require efficiency and ease of implementation. It is a truism in education that teachers are always strapped for time. Designing an assessment methodology that requires large periods of class time for assessment is one of the best ways to ensure it is not widely adopted. 2) Broadly applicable design: Existing attempts to implement systems-oriented instruction span a broad range of subjects and educational levels. The methodology, therefore, needs to be usable in a variety of contexts. 3) Focus on learning: Systems thinking is a skill, so any as- sessment of it should focus on evaluating not what students know, but how they learn. 4) Objective evaluation: Some earlier studies assessing sys- tems-oriented instruction rely heavily on feedback from the participants themselves (Huz et al., 1997; Cavaleri & Sterman, 1997). This feedback is important, particularly in situations where the participants are interested in taking an active role in their own education. However, such data will likely not be as persuasive to teachers and school administrators as objectively calculated cores and indices analogous to those included in standardized tests. In the short term studies may be kept simple, focusing on the performance of students who have received systems-oriented instruction compared to those who have not. However, long- term research plans should include more nuanced comparisons that explore the advantages and disadvantages of various ap- proaches toward systems-oriented curricula. Such comparisons are difficult to make at present due to the dearth of systems- oriented educational programmes. Thus it is my hope that this article will evoke interest both on the part of researchers and practitioners to devote more time and resources to study this promising path for curriculum development in the 21st century. Acknowledgements The author would like to thank Leslie Thiele, Martha Monroe, Stephen Humphrey, Anna Peterson, and Mark Brown for their guidance and assistance. REFERENCES Ackoff, R. L. (1999). Ackoff’s best: His classic writings on manage- ment. John Wiley & Sons: New York. Akimoto, H. (2003). Global air quality and pollution. Science, 302, 1716-1719. doi:10.1126/science.1092666 Agyris, C. (1976). Increasing leadership effectiveness. New York: John Wiley & Sons. Bell, B. I. (1949). Crisis in education: A challenge to American com- placency. New York: Whittlesey House. Bellack, A., & June A. (1969). History of curriculum thought and prac- tice. Review of Educational Research, 39, 283-292. Benjamin, H. R. W. (1939). Saber-tooth curriculum, including other lectures in the history of paleolithic education. New York: McGraw- Hill. Berliner, D. C., & Bingman, V. P. (1997). The manufactured crisis: Myths, fraud, and the attack on America’s public schools. White Plains, NY: Longman Publishers. Bestor, A. (1953). Educational wastelands: A retreat from learning in our public schools. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press. Booth Sweeney, L., & Sterman, J. (2000). Bathtub dynamics: Initial results of a systems thinking inventory. System Dynamics Review, 16, 249-286. doi:10.1002/sdr.198 Boulding, K. (1953). Toward a general theory of growth. Canadian Journal of Economics and Political Science, 19, 326-340. doi:10.2307/138345 Bruner, J. (1953). The process of education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Copyright © 2012 SciRe s. 1318  R. PLATE Copyright © 2012 SciRe s . 1319 Bush, G. W. (2006) . State of the union address. URL http://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/stateoftheunion/2006/ Cavaleri, S, & Sterman, J. (1997). Towards evaluation of systems thinking interventions: A case study. System Dynamics Review, 13, 171-186. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1727(199722)13:2<171::AID-SDR123>3.0. CO;2-9 Cremin, L. (1955). The revolution in American secondary education. Teachers College Record, 56, 295-308. Cremin, L. A. (1961). The transformation of the school: Progressivism in American education. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. Cremin, L. A. (1971). Curriculum-making in the United States. Teach- ers College Record, 73, 207-220. Cohen, J. (2003). Human population: The next half century. Science, 302, 1172-1175. doi:10.1126/science.1088665 Council of Economic Advisors (2005). The economic report of the president. Washi n g t on: Government Printing Offices. Davis, O. L. (1976). Perspectives on curricular development 1776- 1976. Washington: Association for Supervision and Curriculum De- velopment. Dewey, J. (1902). The child and the curriculum. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Dewey, J. (1916). Democracy and education: An introduction to the philosophy of education. New York: MacMillan. Dumaine, B. (1989). What the leaders of tomorrow see. Fortune, 120, 48-54. Egan, K. (1997). The educated mind. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Eliot, C. (1892). Wherein popular education has failed. In E. A. Krug, (Ed.), Charles W. Eliot and popular education. New York: Teachers College, Columbia University. Ellis, A. K. (2004). Exemplars of curriculum theory. New York: Eye on Education, Inc. Essington, T. E., Beaudreau, A., & Wiedenmann, J. (2006). Fishing through marine food webs. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 103, 3171-3191. doi:10.1073/pnas.0510964103 Ezzati, M., Utzinger, J., Cairncross, S., Cohen, A. J., & Singer, B. H. (2005). Environmental risks in the developing world: Exposure indi- cators for evaluating interventions, programmes, and policies. Jour- nal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 59, 15-22. doi:10.1136/jech.2003.019471 Forrester, J. W. (1996). System dynamics and K-12 teachers. Char- lottesville, VA: University of Virginia. G8 Gleneagles (2005). Climate change, clean energy and sustainable development. URL http://www.unglobalcompact.org/docs/about_the_gc/government_su pport/PostG8_Gleneagles_Communique.pdf Gleik, P. H. (2003). Global freshwater resources: Soft-path solutions for the 21st century. Science, 302, 1524-152 8. doi:10.1126/science.1089967 Gore, A. (2006). Interview with terry gross. Washington: National Public Radio. Hofstadter, R. (1963). Anti-intellectualism in American life. New York: Knopf. Huz, S., Andersen, D. F., Richardson, G. P., & Boothroyd, R. (1997). A framework for evaluating systems thinking interventions: An experi- mental approach to mental health system change. System Dynamics Review, 13, 149-169. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1727(199722)13:2<149::AID-SDR122>3.0. CO;2-S Jackson, P. (1992). Conceptions of curriculum and curriculum special- ists. In P. Jackson (Ed.), Handbook of research on curriculum. New York: MacMillan. Jenkins, M. (2003). Prospects for biodiversity. Science, 302, 1175-1177. doi:10.1126/science.1088666 Laszlo, E., Masulli, I., Artigiani, R., & Csanyi, V. (1993). The evolu- tion of cognitive maps: New paradigms for the twenty-first century. Amsterdam: Gordon and Breach Publishers. Marshall, J. D. (2000). Turning points in curriculum: A contemporary American memoir. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill. Meadows, D. (1991). The global citizen. Washington : Island Press. Meyer, A. (1967). An educational history of the American people. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company. Moore, D. W., Monaghan, E. J., & Hartman, D. K. (1997). Values of literacy history. Reading Research Quarterly, 32, 90-102. doi:10.1598/RRQ.32.1.6 National Education Association (1918). The cardinal principles of se- conddary education. In G. Willis, W. H. Schubert, R. V. Bullough, C. Kridel, & J. T. Holton (Eds.), The American curriculum: A docu- mentary history (pp. 153-162). Westport: Greenwood Press. National Commission on Excellence in Education (1983). A nation at risk: The imperative for educational reform. Washington: US De- partment of Education. Odum, H. T. (1994). Ecological and general systems. Niwot: Univer- sity Press of Colorado. Odum, H. T., & Odum, E. C. (2001). A prosperous way down. Boulder: University Press of Colorado. Ornstein, A. C. & Levine D. U. (2000). Foundations of education (7th ed.). Boston: Houghton M ifflin Company. Orr, D. W. (1994). Earth in mind: On education, environment, and the human prospect. Washington: Island Press . Orr, D. W. (2002). The nature of design: Ecology, culture, and human intention. New York: Oxford University Press. Pinar, W., Reynolds, W., Slattery, P., & Taubman, P. (1995). Under- standing curriculum: An introduction to the study of historical and contemporary curriculum discourses. New York: Peter Lang. Rockefeller Brothers Fund (1958). The pursuit of excellence: Education and the future of America. Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Com- pany. Scobey, M.-M., & Graham, G. (1970). To nurture humaneness. Wash- ington: National Education Association. Silberman, C. (1970). Crisis in the Classroom: The Remaking of Ame- rican Education. New York: Random House. Smith, B. O., Stanley, W. O., & Shores, J. H. (1957). Fundamentals of curriculum. Yonkers -on-Hudson, NY: Worl d Boo k Company. Stocking, M. A. (2003). Tropical soils and feed security: The next 50 years. Science, 302, 1356-1359. doi:10.1126/science.1088579 Strong, M. (2001). Forward. In Marten, G. (Ed.) Human Ecology. Ster- ling, VA: Earthscan. Taba, H. (1962). Curriculum development: Theory and practice. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World. Tanner, D., & Tanner, L. (1980). Curriculum development: Theory into practice. Columbus, OH: Merrill. Tanner, D., & Tanner, L. (1990). History of the school curriculum. New York: MacMillan. The Yale Report (1828). The American curriculum: A documentary history. In G. Willis, W. H. Schubert, R. V. Bullough, C. Kridel, & J. T. Holton (Eds.). Westport: Greenwood Press. Tully, S. (2000). Water, water everywhere. Fortune, 141, 342-354. United States Department of Commerce, United States Department of Education, United States Department of Labor (1999). 21st century skills for 21st century jobs. Washington: US Government Printing Office. United States Department of Education (1986). What works: Research about teaching and learning. Washington: US Government Printing Office. United States Department of Education (2006) Meeting the challenge of a changing world: Strengthening education for the 21st century. Washington: US Gover nment Printing Office. Weinstein, G., & Fantini, M. D. (1971). Toward humanistic education: A curriculum of affect. New York: Praeger. Willis, G., Shubert, W., Bullough, R. V., Kridel, C., & Holton, J. T., (Eds.) (1993). The American curriculum: A documented history. Westport: Greenwood Press. Wright, J., & Muller-Landau, H. (2006). The future of tropical forest species. Biotropica, 38, 287-301. doi:10.1111/j.1744-7429.2006.00154.x

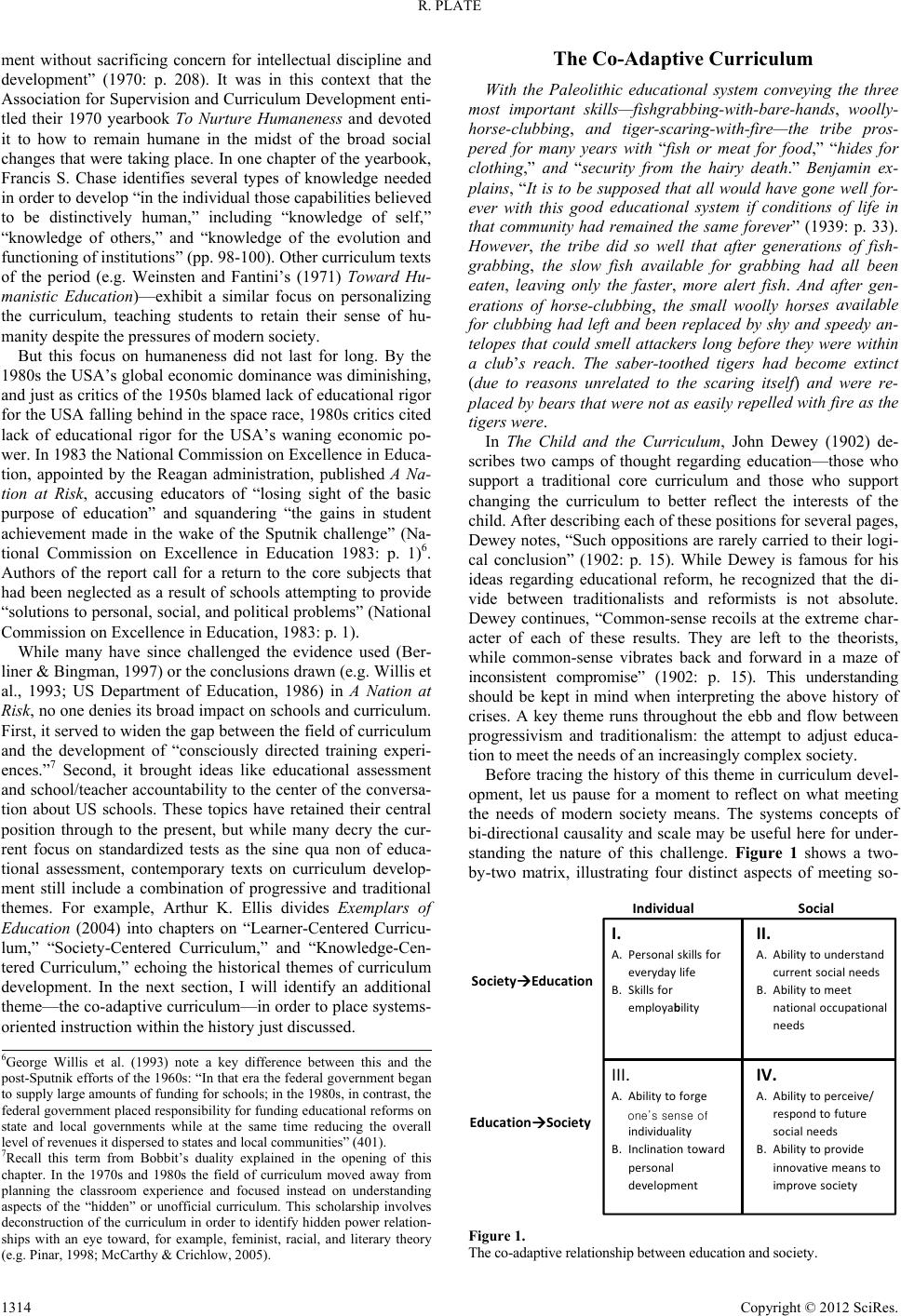

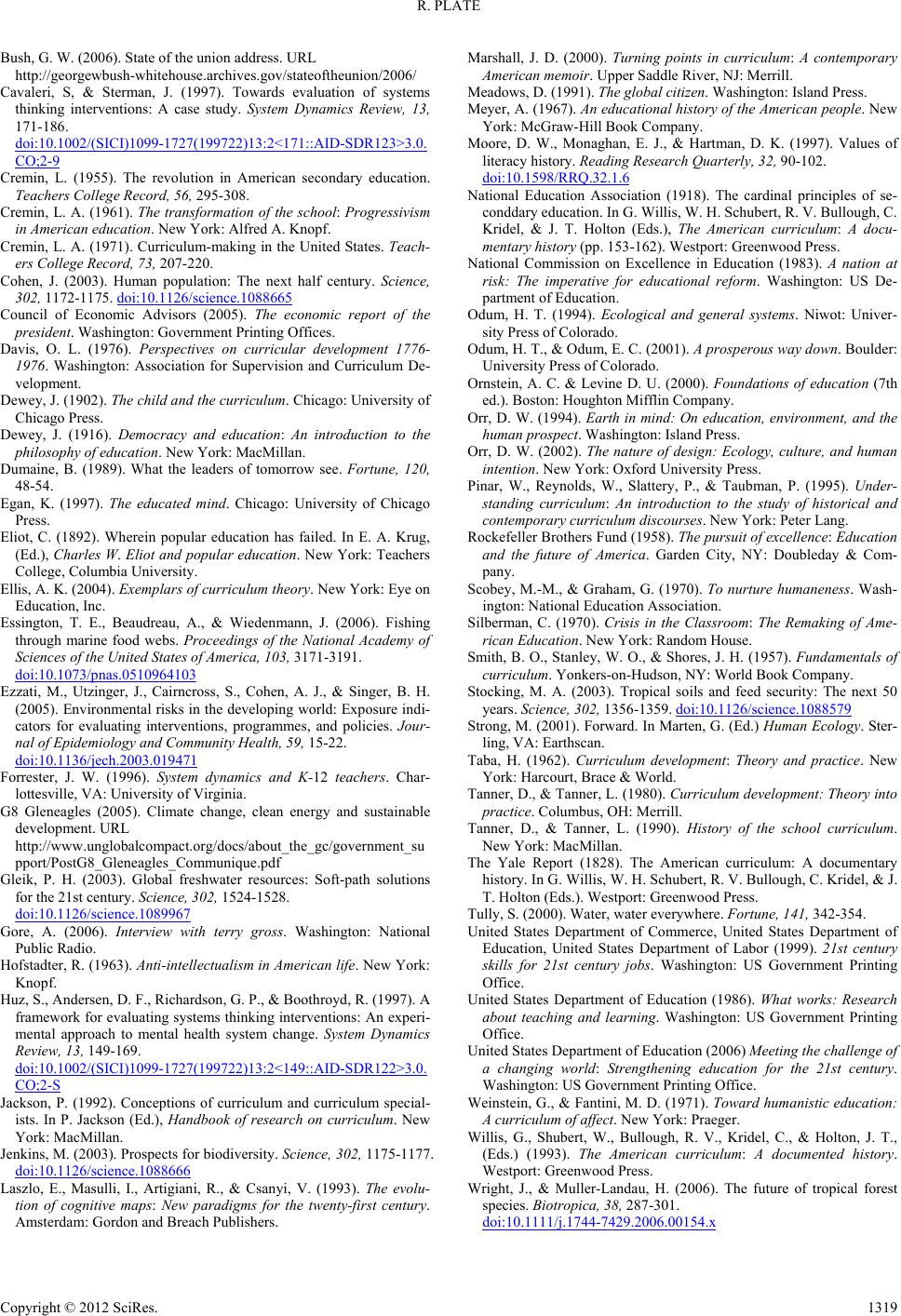

|