Paper Menu >>

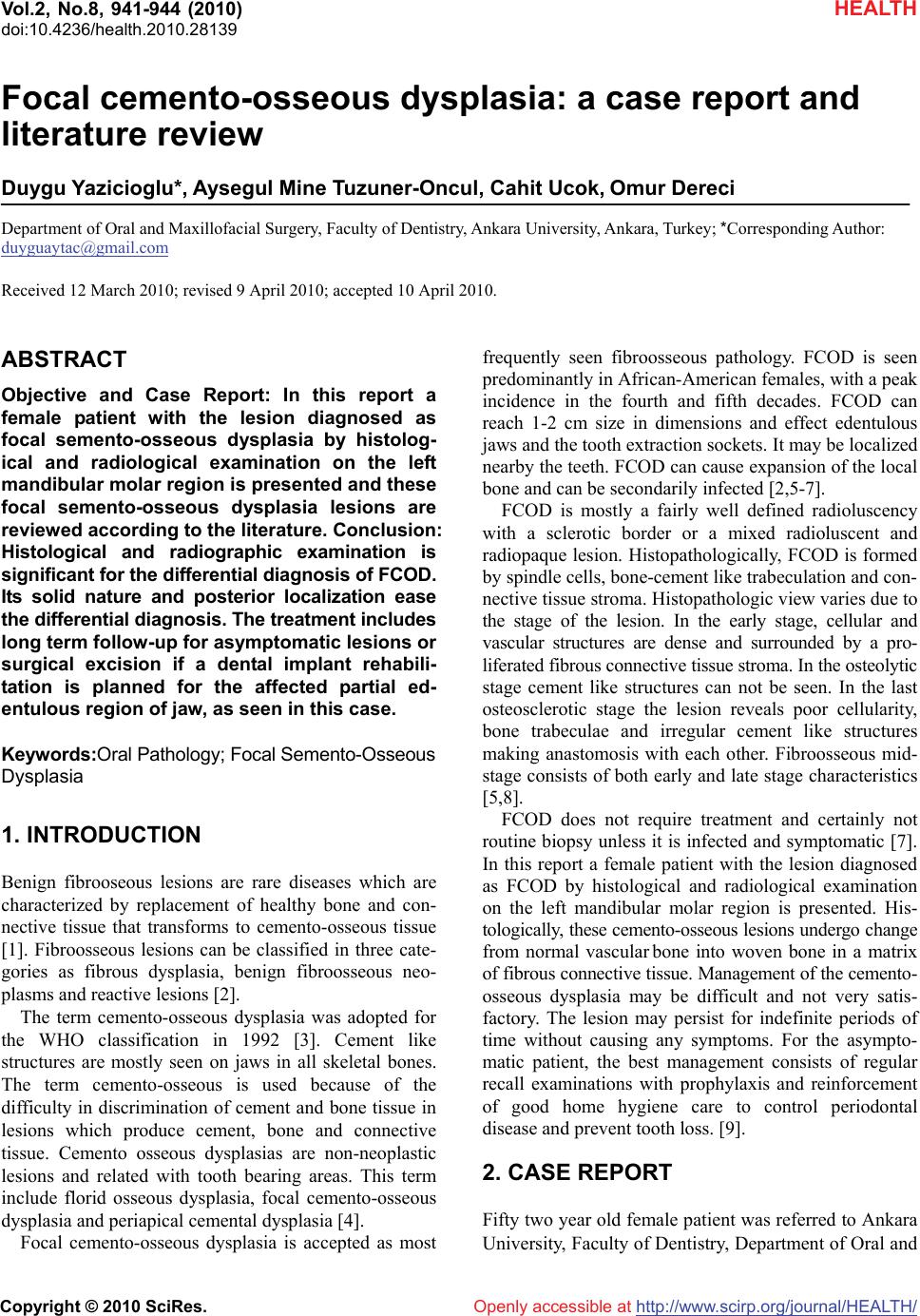

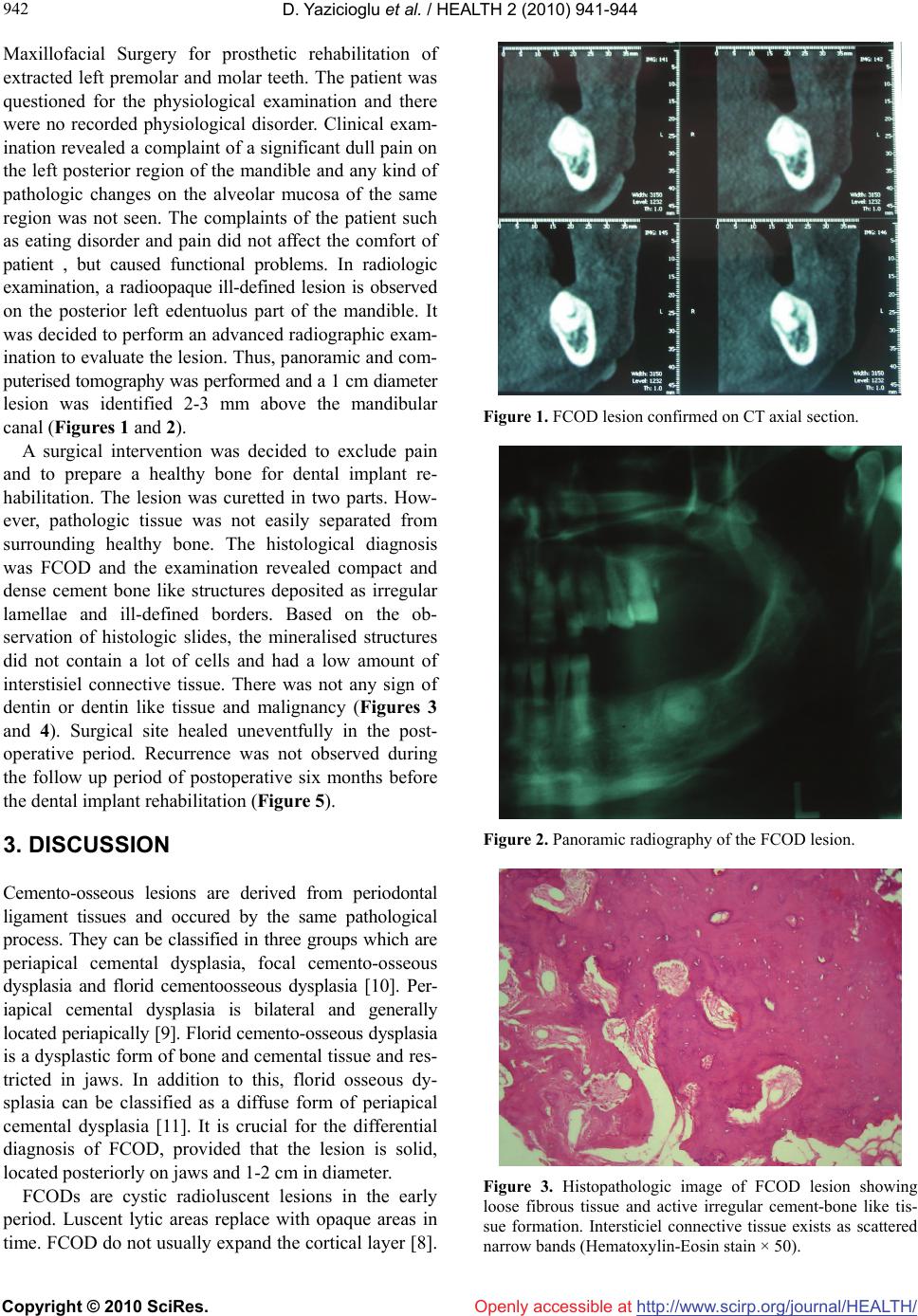

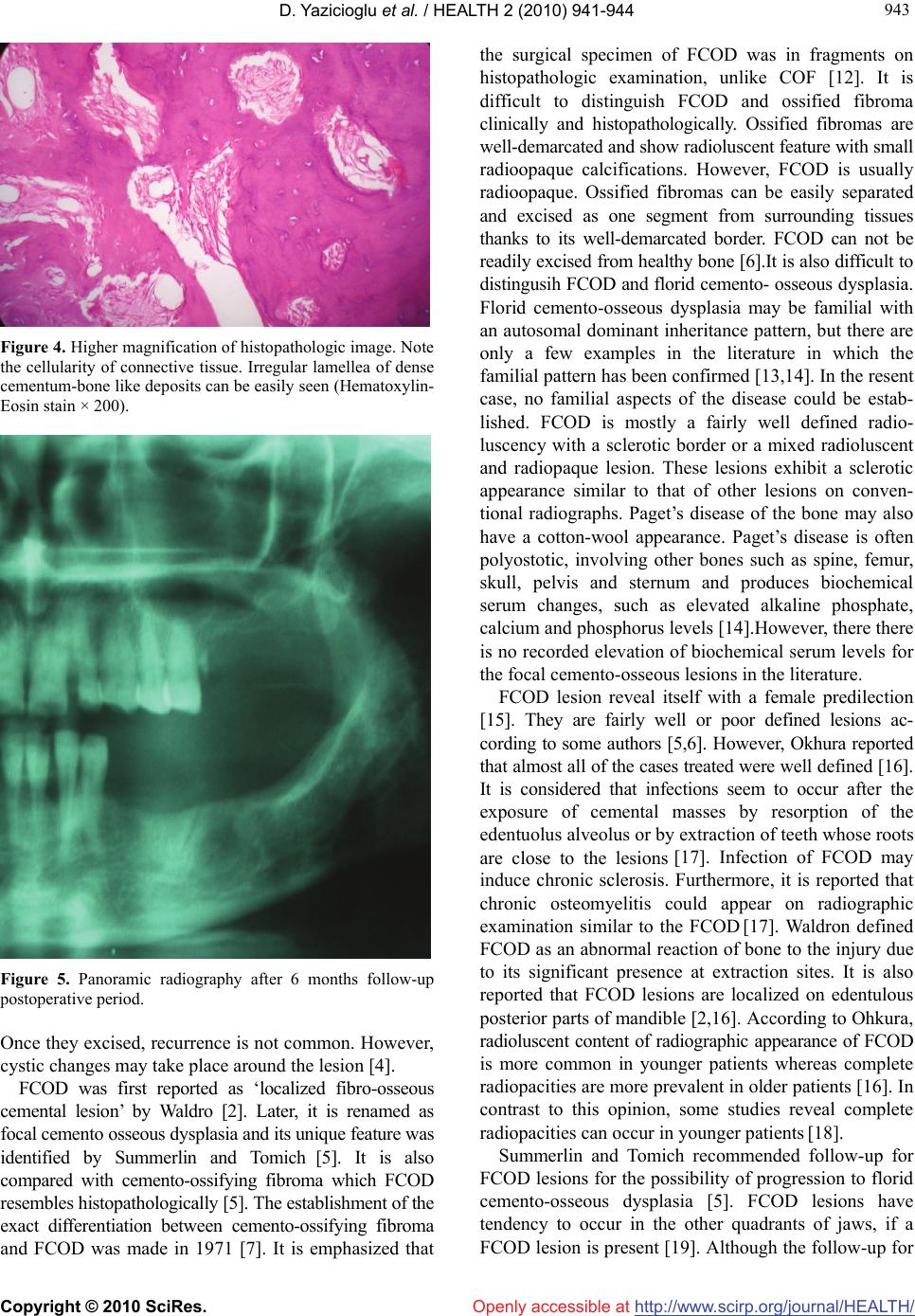

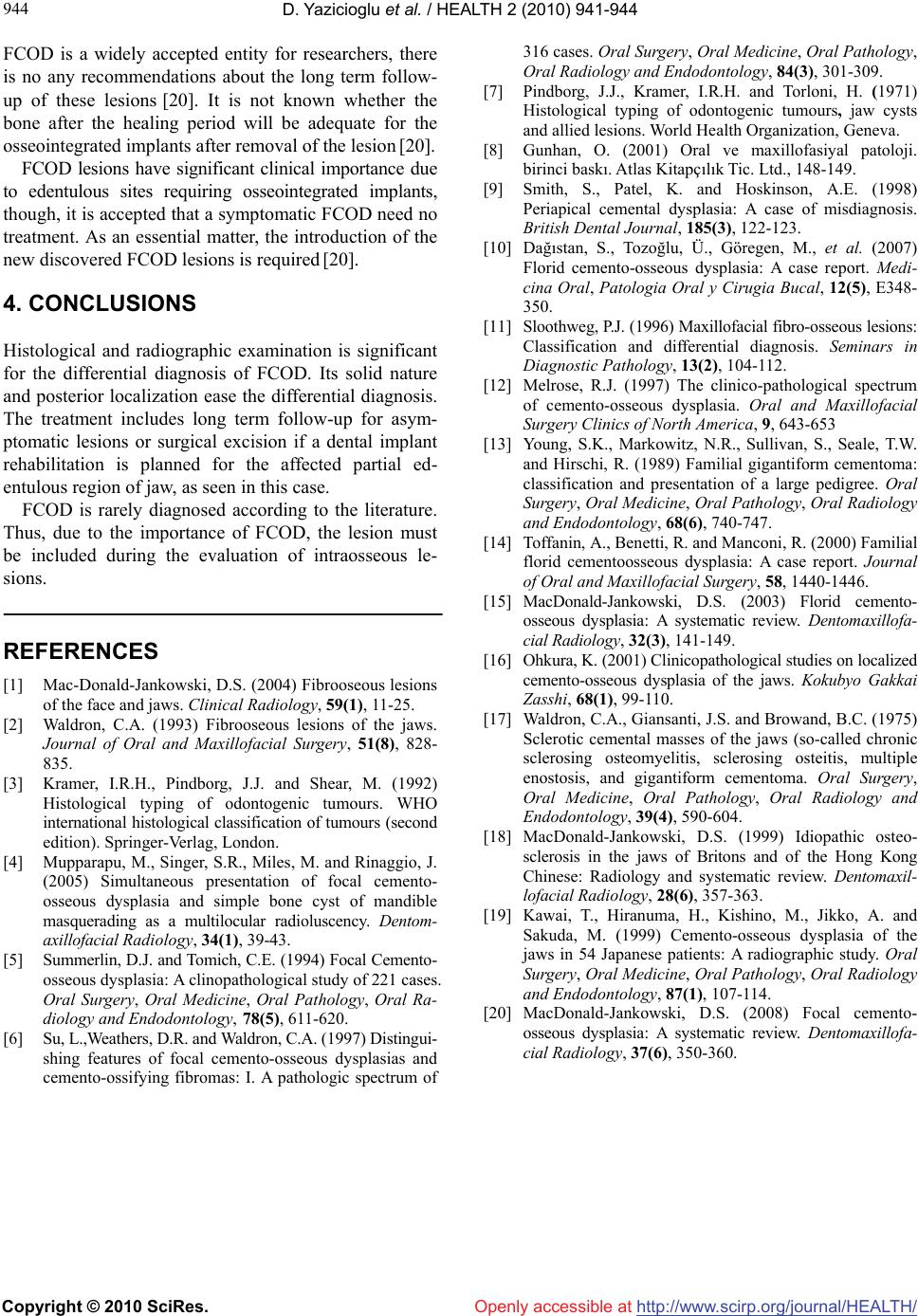

Journal Menu >>

Vol.2, No.8, 941-944 doi:10.4236/health.2010.28139 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journalT / (2010) HEALTH Openly accessible at/HEAL H Focal cemento-osseous dysplasia: a case report and literature review Duygu Yazicioglu*, Aysegul Mine Tuzuner-Oncul, Cahit Ucok, Omur Dereci Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Faculty of Dentistry, Ankara University, Ankara, Turkey; *Corresponding Author: duyguaytac@gmail.com Received 12 March 2010; revised 9 April 2010; accepted 10 April 2010. ABSTRACT Objective and Case Report: In this report a female patient with the lesion diagnosed as focal semento-osseous dysplasia by histolog- ical and radiological examination on the left mandibular molar region is presented and these focal semento-osseous dysplasia lesions are reviewed according to the literature. Conclusion: Histological and radiographic examination is significant for the differential diagnosis of FCOD. Its solid nature and posterior localization ease the differential diagnosis. The treatment includes long term follow-up for asymptomatic lesions or surgical excision if a dental implant rehabili- tation is planned for the affected partial ed- entulous region of jaw, as seen in this case. Keywords:Oral Pathology; Focal Semento-Osseous Dysplasia 1. INTRODUCTION Benign fibrooseous lesions are rare diseases which are characterized by replacement of healthy bone and con- nective tissue that transforms to cemento-osseous tissue [1]. Fibroosseous lesions can be classified in three cate- gories as fibrous dysplasia, benign fibroosseous neo- plasms and reactive lesions [2]. The term cemento-osseous dysplasia was adopted for the WHO classification in 1992 [3]. Cement like structures are mostly seen on jaws in all skeletal bones. The term cemento-osseous is used because of the difficulty in discrimination of cement and bone tissue in lesions which produce cement, bone and connective tissue. Cemento osseous dysplasias are non-neoplastic lesions and related with tooth bearing areas. This term include florid osseous dysplasia, focal cemento-osseous dysplasia and periapical cemental dysplasia [4]. Focal cemento-osseous dysplasia is accepted as most frequently seen fibroosseous pathology. FCOD is seen predominantly in African-American females, with a peak incidence in the fourth and fifth decades. FCOD can reach 1-2 cm size in dimensions and effect edentulous jaws and the tooth extraction sockets. It may be localized nearby the teeth. FCOD can cause expansion of the local bone and can be secondarily infected [2,5-7]. FCOD is mostly a fairly well defined radioluscency with a sclerotic border or a mixed radioluscent and radiopaque lesion. Histopathologically, FCOD is formed by spindle cells, bone-cement like trabeculation and con- nective tissue stroma. Histopathologic view varies due to the stage of the lesion. In the early stage, cellular and vascular structures are dense and surrounded by a pro- liferated fibrous connective tissue stroma. In the osteolytic stage cement like structures can not be seen. In the last osteosclerotic stage the lesion reveals poor cellularity, bone trabeculae and irregular cement like structures making anastomosis with each other. Fibroosseous mid- stage consists of both early and late stage characteristics [5,8]. FCOD does not require treatment and certainly not routine biopsy unless it is infected and symptomatic [7]. In this report a female patient with the lesion diagnosed as FCOD by histological and radiological examination on the left mandibular molar region is presented. His- tologically, these cemento-osseous lesions undergo change from normal vascular bone into woven bone in a matrix of fibrous connective tissue. Management of the cemento- osseous dysplasia may be difficult and not very satis- factory. The lesion may persist for indefinite periods of time without causing any symptoms. For the asympto- matic patient, the best management consists of regular recall examinations with prophylaxis and reinforcement of good home hygiene care to control periodontal disease and prevent tooth loss. [9]. 2. CASE REPORT Fifty two year old female patient was referred to Ankara University, Faculty of Dentistry, Department of Oral and  D. Yazicioglu et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 941-944 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journalT / 942 Openly accessible at/HEALH Maxillofacial Surgery for prosthetic rehabilitation of extracted left premolar and molar teeth. The patient was questioned for the physiological examination and there were no recorded physiological disorder. Clinical exam- ination revealed a complaint of a significant dull pain on the left posterior region of the mandible and any kind of pathologic changes on the alveolar mucosa of the same region was not seen. The complaints of the patient such as eating disorder and pain did not affect the comfort of patient , but caused functional problems. In radiologic examination, a radioopaque ill-defined lesion is observed on the posterior left edentuolus part of the mandible. It was decided to perform an advanced radiographic exam- ination to evaluate the lesion. Thus, panoramic and com- puterised tomography was performed and a 1 cm diameter lesion was identified 2-3 mm above the mandibular canal (Figures 1 and 2). A surgical intervention was decided to exclude pain and to prepare a healthy bone for dental implant re- habilitation. The lesion was curetted in two parts. How- ever, pathologic tissue was not easily separated from surrounding healthy bone. The histological diagnosis was FCOD and the examination revealed compact and dense cement bone like structures deposited as irregular lamellae and ill-defined borders. Based on the ob- servation of histologic slides, the mineralised structures did not contain a lot of cells and had a low amount of interstisiel connective tissue. There was not any sign of dentin or dentin like tissue and malignancy (Figures 3 and 4). Surgical site healed uneventfully in the post- operative period. Recurrence was not observed during the follow up period of postoperative six months before the dental implant rehabilitation (Figure 5). 3. DISCUSSION Cemento-osseous lesions are derived from periodontal ligament tissues and occured by the same pathological process. They can be classified in three groups which are periapical cemental dysplasia, focal cemento-osseous dysplasia and florid cementoosseous dysplasia [10]. Per- iapical cemental dysplasia is bilateral and generally located periapically [9]. Florid cemento-osseous dysplasia is a dysplastic form of bone and cemental tissue and res- tricted in jaws. In addition to this, florid osseous dy- splasia can be classified as a diffuse form of periapical cemental dysplasia [11]. It is crucial for the differential diagnosis of FCOD, provided that the lesion is solid, located posteriorly on jaws and 1-2 cm in diameter. FCODs are cystic radioluscent lesions in the early period. Luscent lytic areas replace with opaque areas in time. FCOD do not usually expand the cortical layer [8]. Figure 1. FCOD lesion confirmed on CT axial section. Figure 2. Panoramic radiography of the FCOD lesion. Figure 3. Histopathologic image of FCOD lesion showing loose fibrous tissue and active irregular cement-bone like tis- sue formation. Intersticiel connective tissue exists as scattered narrow bands (Hematoxylin-Eosin stain × 50).  D. Yazicioglu et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 941-944 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 943 943 Openly accessible at Figure 4. Higher magnification of histopathologic image. Note the cellularity of connective tissue. Irregular lamellea of dense cementum-bone like deposits can be easily seen (Hematoxylin- Eosin stain × 200). Figure 5. Panoramic radiography after 6 months follow-up postoperative period. Once they excised, recurrence is not common. However, cystic changes may take place around the lesion [4]. FCOD was first reported as ‘localized fibro-osseous cemental lesion’ by Waldro [2]. Later, it is renamed as focal cemento osseous dysplasia and its unique feature was identified by Summerlin and Tomich [5]. It is also compared with cemento-ossifying fibroma which FCOD resembles histopathologically [5]. The establishment of the exact differentiation between cemento-ossifying fibroma and FCOD was made in 1971 [7]. It is emphasized that the surgical specimen of FCOD was in fragments on histopathologic examination, unlike COF [12]. It is difficult to distinguish FCOD and ossified fibroma clinically and histopathologically. Ossified fibromas are well-demarcated and show radioluscent feature with small radioopaque calcifications. However, FCOD is usually radioopaque. Ossified fibromas can be easily separated and excised as one segment from surrounding tissues thanks to its well-demarcated border. FCOD can not be readily excised from healthy bone [6].It is also difficult to distingusih FCOD and florid cemento- osseous dysplasia. Florid cemento-osseous dysplasia may be familial with an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern, but there are only a few examples in the literature in which the familial pattern has been confirmed [13,14]. In the resent case, no familial aspects of the disease could be estab- lished. FCOD is mostly a fairly well defined radio- luscency with a sclerotic border or a mixed radioluscent and radiopaque lesion. These lesions exhibit a sclerotic appearance similar to that of other lesions on conven- tional radiographs. Paget’s disease of the bone may also have a cotton-wool appearance. Paget’s disease is often polyostotic, involving other bones such as spine, femur, skull, pelvis and sternum and produces biochemical serum changes, such as elevated alkaline phosphate, calcium and phosphorus levels [14].However, there there is no recorded elevation of biochemical serum levels for the focal cemento-osseous lesions in the literature. FCOD lesion reveal itself with a female predilection [15]. They are fairly well or poor defined lesions ac- cording to some authors [5,6]. However, Okhura reported that almost all of the cases treated were well defined [16]. It is considered that infections seem to occur after the exposure of cemental masses by resorption of the edentuolus alveolus or by extraction of teeth whose roots are close to the lesions [17]. Infection of FCOD may induce chronic sclerosis. Furthermore, it is reported that chronic osteomyelitis could appear on radiographic examination similar to the FCOD [17]. Waldron defined FCOD as an abnormal reaction of bone to the injury due to its significant presence at extraction sites. It is also reported that FCOD lesions are localized on edentulous posterior parts of mandible [2,16]. According to Ohkura, radioluscent content of radiographic appearance of FCOD is more common in younger patients whereas complete radiopacities are more prevalent in older patients [16]. In contrast to this opinion, some studies reveal complete radiopacities can occur in younger patients [18]. Summerlin and Tomich recommended follow-up for FCOD lesions for the possibility of progression to florid cemento-osseous dysplasia [5]. FCOD lesions have tendency to occur in the other quadrants of jaws, if a FCOD lesion is present [19]. Although the follow-up for  D. Yazicioglu et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 941-944 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journalT / 944 FCOD is a widely accepted entity for researchers, there is no any recommendations about the long term follow- up of these lesions [20]. It is not known whether the bone after the healing period will be adequate for the osseointegrated implants after removal of the lesion [20]. Openly accessible at /HEALH FCOD lesions have significant clinical importance due to edentulous sites requiring osseointegrated implants, though, it is accepted that a symptomatic FCOD need no treatment. As an essential matter, the introduction of the new discovered FCOD lesions is required [20]. 4. CONCLUSIONS Histological and radiographic examination is significant for the differential diagnosis of FCOD. Its solid nature and posterior localization ease the differential diagnosis. The treatment includes long term follow-up for asym- ptomatic lesions or surgical excision if a dental implant rehabilitation is planned for the affected partial ed- entulous region of jaw, as seen in this case. FCOD is rarely diagnosed according to the literature. Thus, due to the importance of FCOD, the lesion must be included during the evaluation of intraosseous le- sions. REFERENCES [1] Mac-Donald-Jankowski, D.S. (2004) Fibrooseous lesions of the face and jaws. Clinical Radiology, 59(1), 11-25. [2] Waldron, C.A. (1993) Fibrooseous lesions of the jaws. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, 51(8), 828- 835. [3] Kramer, I.R.H., Pindborg, J.J. and Shear, M. (1992) Histological typing of odontogenic tumours. WHO international histological classification of tumours (second edition). Springer-Verlag, London. [4] Mupparapu, M., Singer, S.R., Miles, M. and Rinaggio, J. (2005) Simultaneous presentation of focal cemento- osseous dysplasia and simple bone cyst of mandible masquerading as a multilocular radioluscency. Dentom- axillofacial Radiology, 34(1), 39-43. [5] Summerlin, D.J. and Tomich, C.E. (1994) Focal Cemento- osseous dysplasia: A clinopathological study of 221 cases. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Ra- diology and Endodontology, 78(5), 611-620. [6] Su, L.,Weathers, D.R. and Waldron, C.A. (1997) Distingui- shing features of focal cemento-osseous dysplasias and cemento-ossifying fibromas: I. A pathologic spectrum of 316 cases. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology and Endodontology, 84(3), 301-309. [7] Pindborg, J.J., Kramer, I.R.H. and Torloni, H. (1971) Histological typing of odontogenic tumours, jaw cysts and allied lesions. World Health Organization, Geneva. [8] Gunhan, O. (2001) Oral ve maxillofasiyal patoloji. birinci baskı. Atlas Kitapçılık Tic. Ltd., 148-149. [9] Smith, S., Patel, K. and Hoskinson, A.E. (1998) Periapical cemental dysplasia: A case of misdiagnosis. British Dental Journal, 185(3), 122-123. [10] Dağıstan, S., Tozoğlu, Ü., Göregen, M., et al. (2007) Florid cemento-osseous dysplasia: A case report. Medi- cina Oral, Patologia Oral y Cirugia Bucal, 12(5), E348- 350. [11] Sloothweg, P.J. (1996) Maxillofacial fibro-osseous lesions: Classification and differential diagnosis. Seminars in Diagnostic Pathology, 13(2), 104-112. [12] Melrose, R.J. (1997) The clinico-pathological spectrum of cemento-osseous dysplasia. Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Clinics of North America, 9, 643-653 [13] Young, S.K., Markowitz, N.R., Sullivan, S., Seale, T.W. and Hirschi, R. (1989) Familial gigantiform cementoma: classification and presentation of a large pedigree. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology and Endodontology, 68(6), 740-747. [14] Toffanin, A., Benetti, R. and Manconi, R. (2000) Familial florid cementoosseous dysplasia: A case report. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, 58, 1440-1446. [15] MacDonald-Jankowski, D.S. (2003) Florid cemento- osseous dysplasia: A systematic review. Dentomaxillofa- cial Radiology, 32(3), 141-149. [16] Ohkura, K. (2001) Clinicopathological studies on localized cemento-osseous dysplasia of the jaws. Kokubyo Gakkai Zasshi, 68(1), 99-110. [17] Waldron, C.A., Giansanti, J.S. and Browand, B.C. (1975) Sclerotic cemental masses of the jaws (so-called chronic sclerosing osteomyelitis, sclerosing osteitis, multiple enostosis, and gigantiform cementoma. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology and Endodontology, 39(4), 590-604. [18] MacDonald-Jankowski, D.S. (1999) Idiopathic osteo- sclerosis in the jaws of Britons and of the Hong Kong Chinese: Radiology and systematic review. Dentomaxil- lofacial Radiology, 28(6), 357-363. [19] Kawai, T., Hiranuma, H., Kishino, M., Jikko, A. and Sakuda, M. (1999) Cemento-osseous dysplasia of the jaws in 54 Japanese patients: A radiographic study. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology and Endodontology, 87(1), 107-114. [20] MacDonald-Jankowski, D.S. (2008) Focal cemento- osseous dysplasia: A systematic review. Dentomaxillofa- cial Radiology, 37(6), 350-360. |