Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

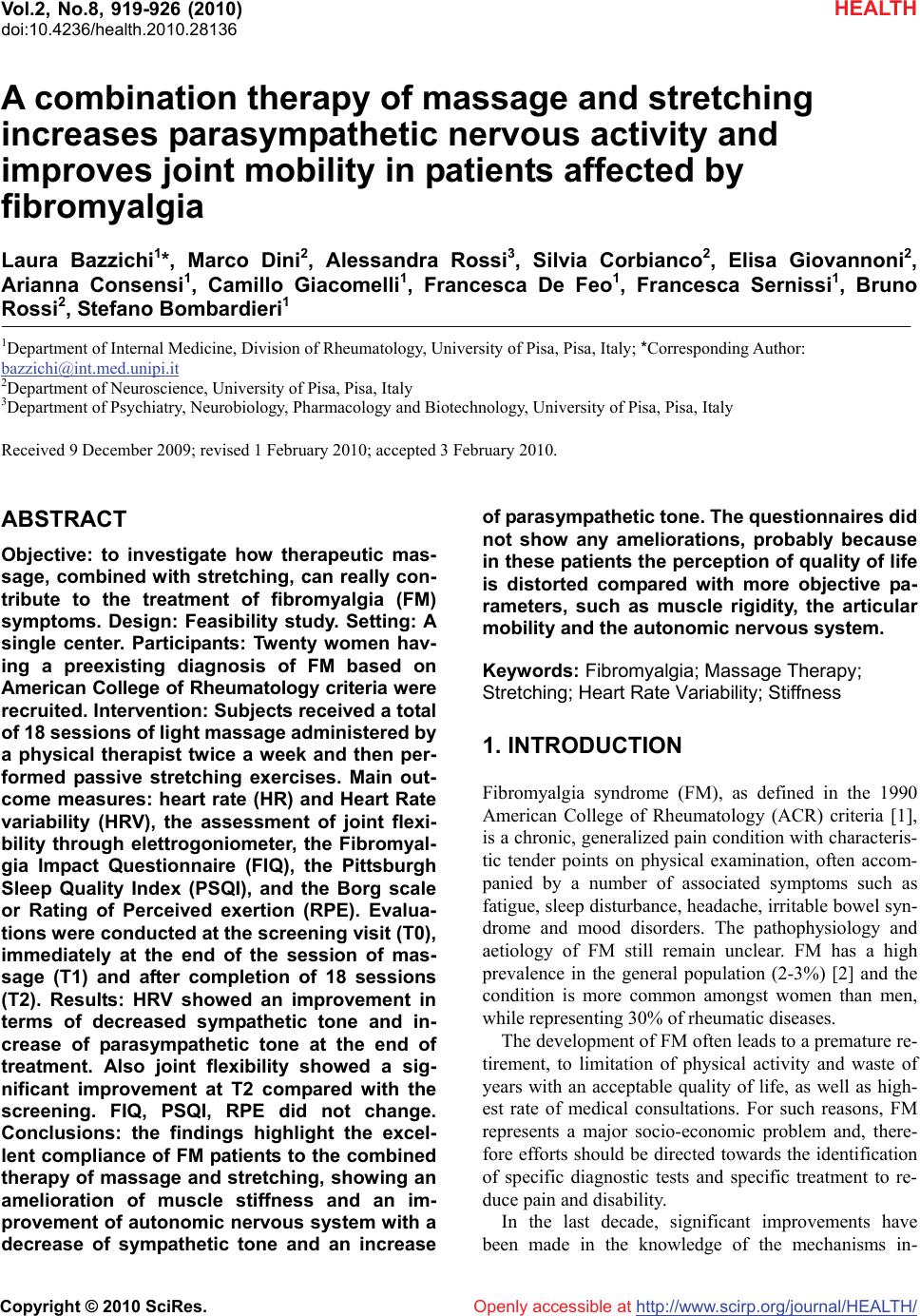

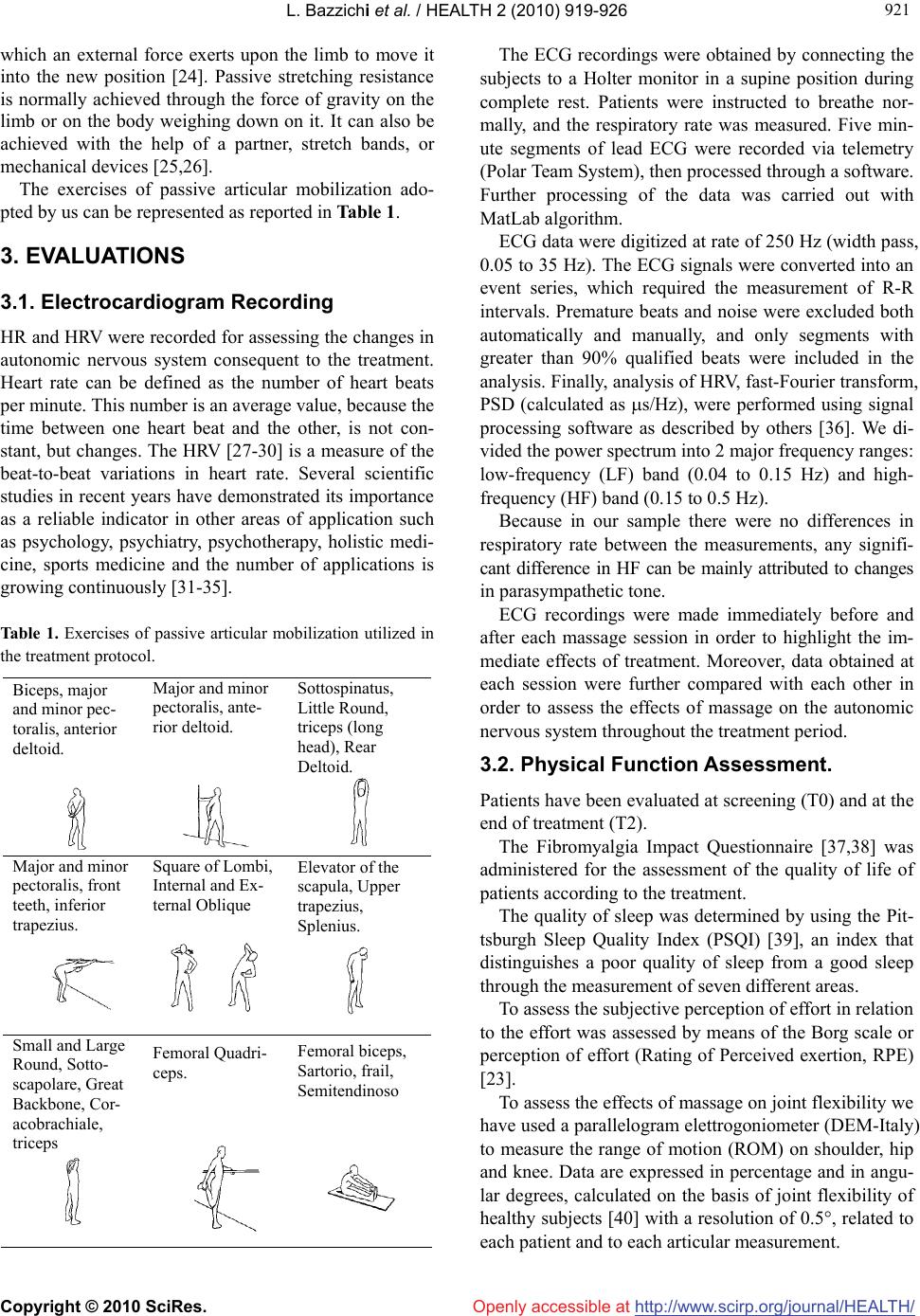

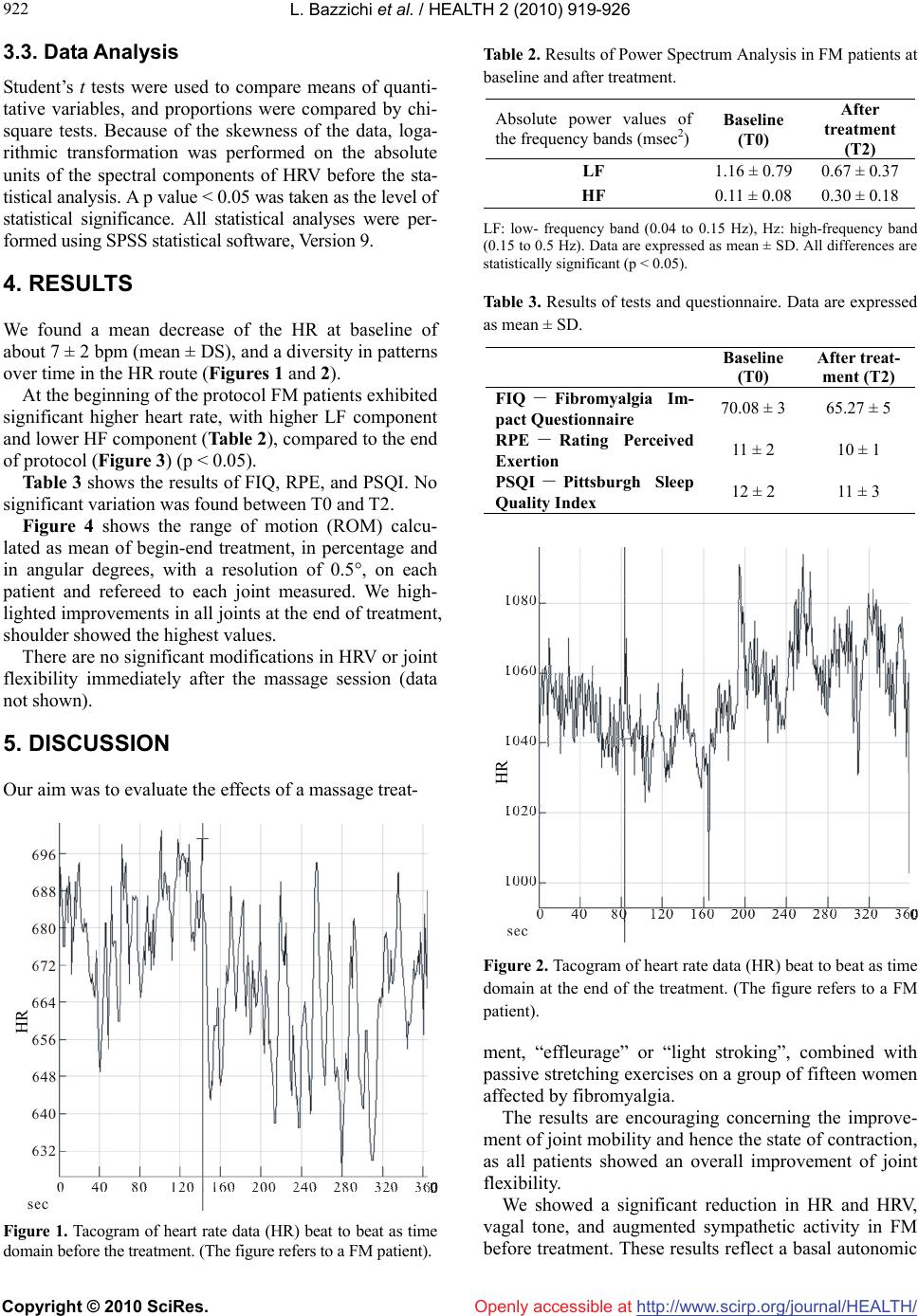

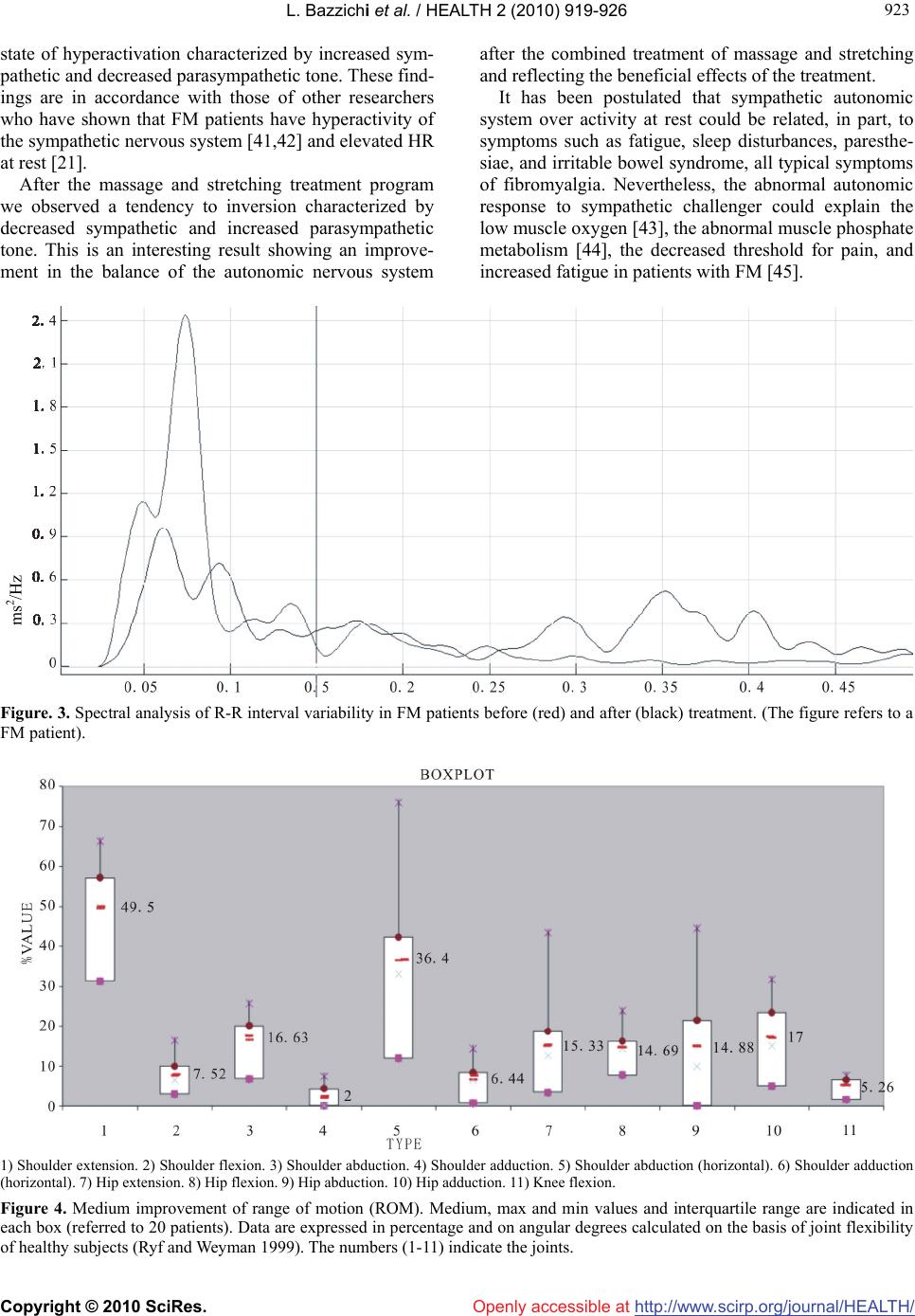

Vol.2, No.8, 919-926 (2010) doi:10.4236/health.2010.28136 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ HEALTH Openly accessible at A combination therapy of massage and stretching increases parasympathetic nervous activity and improves joint mobility in patients affected by fibromyalgia Laura Bazzichi1*, Marco Dini2, Alessandra Rossi3, Silvia Corbianco2, Elisa Giovannoni2, Arianna Consensi1, Camillo Giacomelli1, Francesca De Feo1, Francesca Sernissi1, Bruno Rossi2, Stefano Bombardieri1 1Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Rheumatology, University of Pisa, Pisa, Italy; *Corresponding Author: bazzichi@int.med.unipi.it 2Department of Neuroscience, University of Pisa, Pisa, Italy 3Department of Psychiatry, Neurobiology, Pharmacology and Biotechnology, University of Pisa, Pisa, Italy Received 9 December 2009; revised 1 February 2010; accepted 3 February 2010. ABSTRACT Objective: to investigate how therapeutic mas- sage, combined with stretching, can really con- tribute to the treatment of fibromyalgia (FM) symptoms. Design: Feasibility study. Setting: A single center. Participants: Twenty women hav- ing a preexisting diagnosis of FM based on American College of Rheumatology criteria were recruited. Intervention: Subjects received a total of 18 sessions of light massage administered by a physical therapist twice a week and then per- formed passive stretching exercises. Main out- come measures: heart rate (HR) and Heart Rate variability (HRV), the assessment of joint flexi- bility through elettrogoniometer, the Fibromyal- gia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ), the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), and the Borg scale or Rating of Perceived exertion (RPE). Evalua- tions were conducted at the screening visit (T0), immediately at the end of the session of mas- sage (T1) and after completion of 18 sessions (T2). Results: HRV showed an improvement in terms of decreased sympathetic tone and in- crease of parasympathetic tone at the end of treatment. Also joint flexibility showed a sig- nificant improvement at T2 compared with the screening. FIQ, PSQI, RPE did not change. Conclusions: the findings highlight the excel- lent compliance of FM patients to the combined therapy of massage and stretching, showing an amelioration of muscle stiffness and an im- provement of autonomic nervous system with a decrease of sympathetic tone and an increase of parasympathetic tone. The questionnaires did not show any ameliorations, probably because in these patients the perception of quality of life is distorted compared with more objective pa- rameters, such as muscle rigidity, the articular mobility and the autonomic nervous system. Keywords: Fibromyalgia; Massage Therapy; Stretching; Heart Rate Variability; Stiffness 1. INTRODUCTION Fibromyalgia syndrome (FM), as defined in the 1990 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria [1], is a chronic, generalized pain condition with characteris- tic tender points on physical examination, often accom- panied by a number of associated symptoms such as fatigue, sleep disturbance, headache, irritable bowel syn- drome and mood disorders. The pathophysiology and aetiology of FM still remain unclear. FM has a high prevalence in the general population (2-3%) [2] and the condition is more common amongst women than men, while representing 30% of rheumatic diseases. The development of FM often leads to a premature re- tirement, to limitation of physical activity and waste of years with an acceptable quality of life, as well as high- est rate of medical consultations. For such reasons, FM represents a major socio-economic problem and, there- fore efforts should be directed towards the identification of specific diagnostic tests and specific treatment to re- duce pain and disability. In the last decade, significant improvements have been made in the knowledge of the mechanisms in-  L. Bazzichi et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 919-926 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/Openly accessible at 920 volved in the altered pain threshold of FM patients and new strategies of treatment have been developed or pro- posed. Different medical treatments are used to treat fibromyalgia and beside pharmacological compounds non-pharmacological interventions include psychother- apy, chiropractic, acupuncture, physical therapy and massage [3-12]. There are many studies showing the effect of massage or massage combined with other treatments as progres- sive muscle relaxation or transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulator (TENS), in reducing anxiety, depression, cor- tisol and Corticotropin Releasing Factor-Like Immuno- reactivity levels, pain perception, and stiffness in pa- tients affected by fibromyalgia [13,14]. Moreover it has been showed that massage therapy may increase the number of sleep hours, decrease the sleep movements, reduce substance P levels [15] and improves pain and quality of life related to health (HRQOL) [16]. Other studies confirm only in part these results high- lighting also that benefits of massage in FM are of short term [17], or that the obtained results, even if positive, may not be considered realistic given the low number of the patients studied [18]. These evidence supporting the use of massage for FM are controversial; some works suffers from methodo- logical limitations such as small sample size, inadequate blinding of assessors and an absence of follow-up as- sessments, others found no benefits for massage or short-term benefits. Given these premises and the great request of massage therapy by FM patients, we designed a study to better understand how therapeutic massage can really contrib- ute to the treatment of FM symptoms and how it can affect the quality of life of these patients. For this goal a treatment protocol of rehabilitative massage and stretch- ing exercises has been developed at the Division of Neurorehabilitation of the University of Pisa, for the FM patients recruited by the Division of Rheumatology of the same University. In healthy individuals it has been showed that trigger point massage may have effects on autonomic tone measured by heart rate variability [19], in particular heart rate variability (HRV) analysis revealed a signifi- cant increase in parasympathetic activity, and a decrease in heart rate, systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure have been observed. Some authors [20-22] re- ported that FM patients have hyperactivity of sympa- thetic tone and hypoactivity of parasympathtetic tone, which may be related to the symptomatology, physical and psychological aspects of FM. In light of these evidence a single-center feasibility study was carried out to investigate whether a combined treatment of light massage and stretching, performed by us, could be helpful in treating fibromyalgia. The main outcome measures to verify it were HRV recording, joint flexibility assessing and clinical evaluation. This protocol treatment allowed us to conduct a study for the evaluation and standardization of the effective- ness of massage therapy on such patients. 2. METHODS 2.1. Subjects Twenty women affected by primary FM (aged between 45 and 70 years) were enrolled in the study. Patients, with diagnosis of at least 1 year, were recruited accord- ing to the 1990 American College of Rheumatology cri- teria (ACR criteria) [1]. The concomitant presence of other rheumatic diseases was an exclusion criteria. Patients had not taken any medications known to alter autonomic activity. All patients gave their written con- sent to participate in the study. 2.2. Experimental Protocol The treatment program was carried out 2 time a week for 9 weeks, for a total of 18 sessions. Each session began with the measurement of joint flexibility and continued with the electrocardiographic (ECG) recording for the assessment of heart rate (HR) and heart rate variability (HRV). After these evaluations we proceeded with the mas- sage: it was a light massage, (stroking, effleurage), with the passage of the hands over a large part of the body with constant pressure. This pressure was evaluated by strain gauge, according to about 300-400 gr/cm2. Massage treatment, lasting about 30 minutes, was performed with the patient in “discharge”, or keeping the affected joints in flexion-extension, abdo-adduction and /or intra-extrarotation in order to reduce muscle tension. It began in front of legs, with touch in cauda-cranial di- rection, towards the area of the inguinal lymph nodes, firstly those surface and then deeper. Subsequently mas- sage continued behind the legs, in the same manner and time. In this case however, moving from the area of the calf to the thigh, there were also slight manoeuvres to empty the popliteus lymph nodes of the cable, keeping the knee passively flexed slightly. The last part of massage was devoted to the back and shoulders, with manoeuvres that do not include the area of the spine in the direction of the axillary lymph nodes. Immediately after the massage ECG recording and the measurement of joint flexibility were repeated. After the massage session, passive stretching exercises were ad- ministered to patients, with the aim of assessing the per- ception of stress of these patients, using the Borg scale for the perception of effort (Rating of Perceived exertion, RPE) [23]. Passive stretching is a form of static stretching in  L. Bazzichi et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 919-926 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 921 921 Openly accessible at which an external force exerts upon the limb to move it into the new position [24]. Passive stretching resistance is normally achieved through the force of gravity on the limb or on the body weighing down on it. It can also be achieved with the help of a partner, stretch bands, or mechanical devices [25,26]. The exercises of passive articular mobilization ado- pted by us can be represented as reported in Table 1. 3. EVALUATIONS 3.1. Electrocardiogram Recording HR and HRV were recorded for assessing the changes in autonomic nervous system consequent to the treatment. Heart rate can be defined as the number of heart beats per minute. This number is an average value, because the time between one heart beat and the other, is not con- stant, but changes. The HRV [27-30] is a measure of the beat-to-beat variations in heart rate. Several scientific studies in recent years have demonstrated its importance as a reliable indicator in other areas of application such as psychology, psychiatry, psychotherapy, holistic medi- cine, sports medicine and the number of applications is growing continuously [31-35]. Table 1. Exercises of passive articular mobilization utilized in the treatment protocol. Biceps, major and minor pec- toralis, anterior deltoid. Major and minor pectoralis, ante- rior deltoid. Sottospinatus, Little Round, triceps (long head), Rear Deltoid. Major and minor pectoralis, front teeth, inferior trapezius. Square of Lombi, Internal and Ex- ternal Oblique Elevator of the scapula, Upper trapezius, Splenius. Small and Large Round, Sotto- scapolare, Great Backbone, Cor- acobrachiale, triceps Femoral Quadri- ceps. Femoral biceps, Sartorio, frail, Semitendinoso The ECG recordings were obtained by connecting the subjects to a Holter monitor in a supine position during complete rest. Patients were instructed to breathe nor- mally, and the respiratory rate was measured. Five min- ute segments of lead ECG were recorded via telemetry (Polar Team System), then processed through a software. Further processing of the data was carried out with MatLab algorithm. ECG data were digitized at rate of 250 Hz (width pass, 0.05 to 35 Hz). The ECG signals were converted into an event series, which required the measurement of R-R intervals. Premature beats and noise were excluded both automatically and manually, and only segments with greater than 90% qualified beats were included in the analysis. Finally, analysis of HRV, fast-Fourier transform, PSD (calculated as s/Hz), were performed using signal processing software as described by others [36]. We di- vided the power spectrum into 2 major frequency ranges: low-frequency (LF) band (0.04 to 0.15 Hz) and high- frequency (HF) band (0.15 to 0.5 Hz). Because in our sample there were no differences in respiratory rate between the measurements, any signifi- cant difference in HF can be mainly attributed to changes in parasympathetic tone. ECG recordings were made immediately before and after each massage session in order to highlight the im- mediate effects of treatment. Moreover, data obtained at each session were further compared with each other in order to assess the effects of massage on the autonomic nervous system throughout the treatment period. 3.2. Physical Function Assessment. Patients have been evaluated at screening (T0) and at the end of treatment (T2). The Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire [37,38] was administered for the assessment of the quality of life of patients according to the treatment. The quality of sleep was determined by using the Pit- tsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) [39], an index that distinguishes a poor quality of sleep from a good sleep through the measurement of seven different areas. To assess the subjective perception of effort in relation to the effort was assessed by means of the Borg scale or perception of effort (Rating of Perceived exertion, RPE) [23]. To assess the effects of massage on joint flexibility we have used a parallelogram elettrogoniometer (DEM-Italy) to measure the range of motion (ROM) on shoulder, hip and knee. Data are expressed in percentage and in angu- lar degrees, calculated on the basis of joint flexibility of healthy subjects [40] with a resolution of 0.5°, related to each patient and to each articular measurement.  L. Bazzichi et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 919-926 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 922 Openly accessible at 3.3. Data Analysis Student’s t tests were used to compare means of quanti- tative variables, and proportions were compared by chi- square tests. Because of the skewness of the data, loga- rithmic transformation was performed on the absolute units of the spectral components of HRV before the sta- tistical analysis. A p value < 0.05 was taken as the level of statistical significance. All statistical analyses were per- formed using SPSS statistical software, Version 9. 4. RESULTS We found a mean decrease of the HR at baseline of about 7 ± 2 bpm (mean ± DS), and a diversity in patterns over time in the HR route (Figures 1 and 2). At the beginning of the protocol FM patients exhibited significant higher heart rate, with higher LF component and lower HF component (Table 2), compared to the end of protocol (Figure 3) (p < 0.05). Table 3 shows the results of FIQ, RPE, and PSQI. No significant variation was found between T0 and T2. Figure 4 shows the range of motion (ROM) calcu- lated as mean of begin-end treatment, in percentage and in angular degrees, with a resolution of 0.5°, on each patient and refereed to each joint measured. We high- lighted improvements in all joints at the end of treatment, shoulder showed the highest values. There are no significant modifications in HRV or joint flexibility immediately after the massage session (data not shown). 5. DISCUSSION Our aim was to evaluate the effects of a massage treat- Figure 1. Tacogram of heart rate data (HR) beat to beat as time domain before the treatment. (The figure refers to a FM patient). Table 2. Results of Power Spectrum Analysis in FM patients at baseline and after treatment. Absolute power values of the frequency bands (msec2) Baseline (T0) After treatment (T2) LF 1.16 ± 0.79 0.67 ± 0.37 HF 0.11 ± 0.08 0.30 ± 0.18 LF: low- frequency band (0.04 to 0.15 Hz), Hz: high-frequency band (0.15 to 0.5 Hz). Data are expressed as mean ± SD. All differences are statistically significant (p < 0.05). Table 3. Results of tests and questionnaire. Data are expressed as mean ± SD. Baseline (T0) After treat- ment (T2) FIQ -Fibromyalgia Im- pact Questionnaire 70.08 ± 3 65.27 ± 5 RPE-Rating Perceived Exertion 11 ± 2 10 ± 1 PSQI -Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index 12 ± 2 11 ± 3 HR Figure 2. Tacogram of heart rate data (HR) beat to beat as time domain at the end of the treatment. (The figure refers to a FM patient). HR ment, “effleurage” or “light stroking”, combined with passive stretching exercises on a group of fifteen women affected by fibromyalgia. The results are encouraging concerning the improve- ment of joint mobility and hence the state of contraction, as all patients showed an overall improvement of joint flexibility. We showed a significant reduction in HR and HRV, vagal tone, and augmented sympathetic activity in FM before treatment. These results reflect a basal autonomic  L. Bazzichi et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 919-926 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 923 923 state of hyperactivation characterized by increased sym- pathetic and decreased parasympathetic tone. These find- ings are in accordance with those of other researchers who have shown that FM patients have hyperactivity of the sympathetic nervous system [41,42] and elevated HR at rest [21]. After the massage and stretching treatment program we observed a tendency to inversion characterized by decreased sympathetic and increased parasympathetic tone. This is an interesting result showing an improve- ment in the balance of the autonomic nervous system after the combined treatment of massage and stretching and reflecting the beneficial effects of the treatment. It has been postulated that sympathetic autonomic system over activity at rest could be related, in part, to symptoms such as fatigue, sleep disturbances, paresthe- siae, and irritable bowel syndrome, all typical symptoms of fibromyalgia. Nevertheless, the abnormal autonomic response to sympathetic challenger could explain the low muscle oxygen [43], the abnormal muscle phosphate metabolism [44], the decreased threshold for pain, and increased fatigue in patients with FM [45]. ms2/Hz Figure. 3. Spectral analysis of R-R interval variability in FM patients before (red) and after (black) treatment. (The figure refers to a FM patient). 1) Shoulder extension. 2) Shoulder flexion. 3) Shoulder abduction. 4) Shoulder adduction. 5) Shoulder abduction (horizontal). 6) Shoulder adduction (horizontal). 7) Hip extension. 8) Hip flexion. 9) Hip abduction. 10) Hip adduction. 11) Knee flexion. Figure 4. Medium improvement of range of motion (ROM). Medium, max and min values and interquartile range are indicated in each box (referred to 20 patients). Data are expressed in percentage and on angular degrees calculated on the basis of joint flexibility of healthy subjects (Ryf and Weyman 1999). The numbers (1-11) indicate the joints. Openly accessible at  L. Bazzichi et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 919-926 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 924 Openly accessible at Reduction in parasympathetic tone was found at rest also in some HRV studies on patients affected by panic disorder [46], generalized anxiety disorder [47], depres- sion [48] and post traumatic stress disorder [49]. Perhaps this finding is characteristic of anxiety disorders or de- pression in general and is not specific for FM, reflecting a non specific anxiety-related response in patients with FM. In summary, at rest FM patients exhibit sympathetic hyperactivity and concomitantly reduced parasympa- thetic activity. We found the maximum improvement of joint flexi- bility in shoulder, this is an interesting finding consider- ing that FM patients often say “they have the world on their shoulders”. While we found that the combined treatment of mas- sage and stretching FM patients improved the articular mobility and autonomic nervous system, other authors [50] suggest no consistent immediate or long-term ef- fects on the autonomic nervous system of healthy mid- dle-aged and elderly subjects after connective tissue massage. Unexpectedly the FIQ, Borg RPE and PSQI ques- tionnaire did not show any improvements. This discrep- ancy may be explained considering that, as reported in the literature [51], in these patients is amplified the per- ception of quality of life in its various components and relationships, with respect to more objective parameters, such as muscle rigidity, articular movement and the sympatho-vagal balance. We must make a consideration regarding to the Borg questionnaire: the perception of fatigue did not change after treatment, but we must consider the fact that at T2 patients joint flexibility increased, then they are able to perform wider movements with equal effort, then the effort is indeed decreased. 6. STUDY LIMITATIONS The limitations of the present study are the lack of psy- chiatric evaluations of FM patients, given that HRV al- teration has been found in mood disorders, and the lack of a control sample. 7. CONCLUSIONS In conclusion our protocol has highlighted the excellent compliance of patients suffering from fibromyalgia with a combined treatment of massage and stretching; pa- tients show an amelioration of muscle stiffness and of the parasympathetic component. The questionnaires did not show any ameliorations, probably because in these patients the perception of quality of life is distorted compared with more objective parameters, such as mus- cle rigidity, the joint flexibility and the autonomic nerv- ous system. Our research highlights the need for a standardization of treatment, both in terms of method (technique) and application (pressure of operator). REFERENCES [1] Wolfe, F., Smythe Smythe, H.A., Yunus, M.B., Bennett, R.M., Bombardier, C., Goldenberg, D.L., Tugwell, P, Campbell, S.M., Abeles, M., Clark, P., Fam, A.G., Farber, S.J., Fiechtner, J.J., Franklin, C.M., Gatter, R.A., Hamaty, D., Lessard, J., Lichtbroun, A.S,. Masi, A.T., McCain, G.A., Reynolds, J., Romano, T.J., Russell, I.J. and Sheon, R.P. (1990) The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of fibromyalgia. Re- port of the multicenter criteria committee. Arthritis Rheum, 33(2), 160-172. [2] Ablin, J., Neumann, L. and Buskila, D. (1999) Patho- genesis of fibromyalgia—a review. Joint Bone Spine 2008, 75(3), 273-279. [3] Berman, B.M., Ezzo, J., Hadhazy, V. and Swyers, J.P. (1999) Is acupuncture effective in the treatment of fi- bromyalgia? Journal of Family Practice, 48(3), 213-218. [4] Blunt, K.L., Rajwani, M.H. and Guerriero, R.C. (1997) The effectiveness of chiropractic management of fi- bromyalgia patients. Journal of Manipulative and Phy- siological Therapeutics, 20(6), 389-399. [5] Buckelew, S.P., Conway, R., Parker, J., Deuser, W.E., Read, J., Witty, T.E., Hewett, J.E., Minor, M, Johnson, J.C., Van Male, L., McIntosh, M.J., Nigh, M. and Kay, D.R. (1998) Biofeedback/relaxation training and exercise interventions for fibromyalgia. Arthritis Care & Research, 11(3), 196-209. [6] Busch, A., Schachter, C.L., Peloso, P.M. and Bombardier, C. (2003) Exercise for treating fibromyalgia syndrome. Evidence-Based Nursing, 6, 50-51. [7] Singh, B.B., Berman, B.M. and Creamer, P. (1998) A pilot study of cognitive behavioral therapy in fibromyal- gia. Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine, 4(2), 67-70. [8] Williams, D.A. (2003) Psychological and behavioral therapies in fibromyalgia and related syndromes. Best Practice & Research Clinical Rheumatology, 17(4), 649- 665. [9] Field, T.M. (1998) Massage therapy effects. American Psychologist, 53(12), 1270-1281. [10] Tsao, J.C. (2007) Effectiveness of Massage Therapy for Chronic, Non-malignant Pain: A Review. Evidence- Based Complement Alternative Medicine, 4(2), 165-179. [11] Hassett, A.L., Radvanski, D.C., Vaschillo, E.G., Vaschillo, B., Sigal, L.H., Karavidas, M.K. Buyske, S. and Lehrer, P.M. (2007) A pilot study of the efficacy of heart rate variability (HRV) biofeedback in patients with fi- bromyalgia. Applied Psychophysiology & Biofeedback, 32, 1-10. [12] Jentoft, E.S., Kvalvik, A.G. and Mengshoel, A.M. (2001) Effects of pool-based and land-based aerobic exercise on women with fibromyalgia/chronic widespread muscle pain. Arthritis & Rheumatism, 45(1), 42-47. [13] Sunshine, W., Field, T.M., Quintino, O., Fierro, K., Kuhn, C., Burman, I. and Schanberg, S. (1996) Fibromyalgia  L. Bazzichi et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 919-926 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/Openly accessible at 925 925 benefits from massage therapy and transcutaneous elec- trical stimulation. Journal of Clinical Rheumatology, 2(1), 18-22. [14] Lund, I., Lundeberg, T., Carleson, J., Sönnerfors, H., Uhrlin, B. and Svensson, E. (2006) Corticotropin releas- ing factor in urine—a possible biochemical marker of fi- bromyalgia. Responses to massage and guided relaxation. Neuroscience Letter, 403(1-2), 166-171. [15] Field, T., Diego, M., Cullen, C., Hernandez-Reif, M. Sun- shine, W. and Douglas, S. (2002) Fibromyalgia pain and substance P decrease and sleep improves after massage therapy. Journal of Clinical Rheumatology, 8(2), 72-76. [16] Ekici, G., Bakar, Y., Akbayrak, T. and Yuksel, I. (2009) Comparison of manual lymph drainage therapy and con- nective tissue massage in women with fibromyalgia: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics, 32(2), 127-133. [17] Brattberg, G. (1999) Connective tissue massage in the treatment of fibromyalgia. European Journal of Pain, 3(3), 235-244. [18] Gordon, C., Emiliozzi, C. and Zartarian, M. (2006) Use of a mechanical massage technique in the treatment of fibromyalgia: A preliminary study. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 87(1), 145-147. [19] Takamoto, K., Sakai, S., Hori, E., Urakawa, S., Umeno, K., Ono, T. and Nishijo, H. (2009) Compression on trig- ger points in the leg muscle increases parasympathetic nervous activity based on heart rate variability. Journal of Physiological Science, 59(3), 191-197. [20] Cohen, H., Neumann, L., Shore, M., Amir, M., Cassuto, Y. and Buskila, D. (2000) Autonomic dysfunction in pa- tients with fibromyalgia: Application of power spectral analysis of heart rate variability. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism, 29(4), 217-227. [21] Martínez-Lavín, M., Hermosillo, A.G., Rosas, M. and Soto, M.E. (1998) Circadian studies of autonomic nerv- ous balance in patients with fibromyalgia: A heart rate variability analysis. Arthritis & Rheumatism, 41(11), 1966-1971. [22] Vaerøy, H., Qiao, Z.G., Mørkrid, L. and Førre, O. (1989) Altered sympathetic nervous system response in patients with fibromyalgia(fibrositis syndrome). Journal of Rheu- matology, 16(11), 1460-1465. [23] Borg, G. (1998) Borg’s perceived exertion and pain scales. Human Kinetics, Stockholm. [24] Kurz, T. (1994) Stretching Scientifically: A Guide to Flexibility Training. 3rd Edition, Stadion Publishing, Is- land Pond. [25] Alter, M. (1988) Science of Stretching. Leisure Press, West Point. [26] Alter, M. (1990) Sport Stretch. Leisure Press, West Point. [27] Cohen, H., Matar, M.A., Kaplan, Z. and Kotler, M. (1999) Power Spectral analysis of heart rate variability in psy- chiatry. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 68(2), 59- 66. [28] Kamath, M.V. and Fallen, E.L. (1993) Power spectral analysis of heart rate variability: A noninvasive signature of cardiac autonomic function. Critical Reviews in Bio- medical Engineering, 21(3), 245-311. [29] Malik, M. and Camm, A.J. (1990) Heart rate variability. Clinical Cardiology, 13, 570-576. [30] Van Ravenswaaij-Arts, C.M.A., Kollèe, L.A.A., Hopman, J.C.V., Stoelinga, G.B.A. and Van Geijn, H.P. (1993) Heart rate variability. Annals of Internal Medicine, 118, 436-447. [31] Keary, T.A., Hughes, J.W. and Palmieri, P.A. (2009) Women with posttraumatic stress disorder have larger decreases in heart rate variability during stress tasks. In- ternational Journal of Psychophysiology, 73(3), 257-264. [32] Licht, C.M., de Geus, E.J., van Dyck, R. and Penninx, B.W. (2009) Association between Anxiety Disorders and Heart Rate Variability in The Netherlands Study of De- pression and Anxiety (NESDA). Psychosomatic Medi- cine, 71, 508-518. [33] Miu, A.C., Heilman, R.M. and Miclea, M. (2009) Re- duced heart rate variability and vagal tone in anxiety: Trait versus state, and the effects of autogenic training. Autonomic Neuroscience, 145(1-2), 99-103. [34] Yeragani, V.K., Pohl, R., Berger, R., Balon, R., Ramesh, C., Glitz, D., Srinivasan, K. and Weinberg, P. (1993) De- creased heart rate variability in panic disorder patients: A study of power-spectral analysis of heart rate. Psychiatry Research, 46(1), 89-103. [35] Jeong, I., Jun, S., Park, S., Jung, S., Shin, T. and Yoon, H. (2008) A Research for evaluation on stress change via thermotherapy and massage. Conference Proceedings of IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, 4820-4823. [36] (1996) Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electro- physiology: Heart rate variability. Standards of meas- urement, physiological interpretation, and clinical use. Circulation, 93, 1043-1065. [37] Burckhardt, C.S., Clark, S.R. and Bennett, R.M. (1991) The fibromyalgia impact questionnaire: Development and validation. Journal of Rheumatology, 18(5), 728- 733. [38] Sarzi-Puttini, P., Atzeni, F., Fiorini, T., Panni, B., Randisi, G., Turiel, M. and Carrabba, M. (2003) Validation of an Italian version of the Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ-I). Clinical Experimental Rheumatology, 21(4), 459-464. [39] Buysse, D.J., Reynolds, C.F. 3rd, Monk, T.H., Berman, S.R. and Kupfer, D.J. (1989) The Pittsburgh Sleep Qual- ity Index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Research, 28(2), 193-213. [40] Ryf, C. and Weymann, A. (1999) AO neutral-O- method. Thieme, Stuttgart. [41] Bengtsson, A. and Bengtsson, M. (1988) Regional sym- pathetic blockade in primary fibromyalgia. Pain, 33(2), 161-167. [42] Cohen, H., Neumann, L., Shore, M., Amir, M., Cassuto, Y. and Buskila, D. (2000) Autonomic dysfunction in pa- tients with fi- bromyalgia: application of power spectral analysis of heart rate variability. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism, 29(4), 217-227. [43] Lund, N., Bengtsson, A. and Thorborg, P. (1986) Muscle tissue oxygen pressure in primary fibromyalgia. Scandi- navian Journal of Rheumatology, 15(2), 165-173. [44] Bengtsson, A., Henriksson, K.G. and Larsson, J. (1986) Reduced high-energy phosphate levels in the painful muscles of patients with primary fibromyalgia. Arthritis & Rheumatism, 29(7), 817-821. [45] Lefkowitz, R., Hoffman, B. and Taylor, P. (1991) Neu-  L. Bazzichi et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 919-926 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/Openly accessible at 926 rohumoral transmission: The autonomic and somatic nervous system. In: Goodman-Gilman Arall, T., Ed. The pharmacological basis of therapeutics. International Edi- tion, McGraw-Hill, New York, 84-121. [46] Yeragani, V.K., Pohl, R., Berger, R., Balon, R., Ramesh, C., Glitz, D., Srinivasan, K. and Weinberg, P. (1993) De- creased heart rate variability in panic disorder patients: A study of power-spectral analysis of heart rate. Psychiatry Research, 46(1), 89-103. [47] Rechlin, T., Weis, M., Spitzer, A. and Kaschka, W.P. (1994) Are affective disorders associated with alterations of heart rate variability? Journal of Affective Disorders, 32(4), 271-275. [48] Rechlin, T., Weis, M. and Kaschka, W.P. (1995) Is diur- nal variation of mood associated with parasympathetic activity? Journal of Affective Disorders, 34(3), 249-255. [49] Cohen, H., Kotler, M., Matar, M.A., Kaplan, Z., Mio- downik, H. and Cassuto, Y. (1997) Power spectral analy- sis of heart rate variability in posttraumatic stress disor- der patients. Biological Psychiatry, 41(5), 627-629. [50] Reed, B.V. and Held, J.M. (1988) Effects of sequential connective tissue massage on autonomic nervous system of middle-aged and elderly adults. Physical Therapy, 68(8), 1231-1234. [51] Nielens, H., Boisset, V. and Masquelie, E. (2000) Fitness and Perceived Exertion in Patients with Fibromyalgia Syndrome. Clinical Journal of Pain, 16(3), 209-213. |