Psychology 2012. Vol.3, Special Issue, 749-755 Published Online September 2012 in SciRes (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/psych) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/psych.2012.329113 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 749 Grade Retention and Seventh-Grade Depression Symptoms in the Course of School Dropout among High-Risk Adolescents* Cintia V. Quiroga1, Michel Janosz2, John S. Lyons1, Alexandre J. S. Morin3 1School of Psychology and Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada 2School Environment Research Group and University of Montreal Public Health Research Institute, University of Montreal, Montreal, Canada 3Center for Positive Psychology and Education, University of Western Sydney, Sydney, Australia Email: cquiroga@uottawa.ca Received June 10th, 2012; revised July 11th, 2012; accepted August 14th, 2012 The relationship between grade retention and adolescent depression in the course of school dropout is poorly understood. Improving knowledge of the mechanisms involving these variables would shed light on at-risk youth development. This study examines whether depression in adolescence moderates the rela- tionship between grade retention and school dropout in a high-risk sample. Seventh-grade students (n = 453) from two low-SES secondary schools in Montreal (Quebec, Canada) were followed from 2000 to 2006. Self-reported lifetime and seventh-grade depression were measured with the Inventory to Diagnose Depression. Primary school grade retention, and secondary school dropout status was obtained through the Ministry of Education of Quebec registries. Sixteen percent of participants reported lifetime depres- sion, and 13% reported depression in seventh-grade. Nearly one third (32%) of the sample dropped out of school. Logistic regression models were used to estimate moderation effects predicting school dropout six years later. Findings indicated that students with grade retention were 5.54 times more likely to drop out of school. Depression in seventh grade increased by 2.75 times the likelihood of school dropout. The probability of dropping out for adolescents combining both grade retention and seventh-grade depression was 7.26 times higher than it was for those reporting grade retention only. The moderating effect of de- pression was similar for boys and girls. Depression is a significant vulnerability factor of low educational attainment aggravating the risk associated with grade retention. Experiencing depression at the beginning of secondary school can interfere with school perseverance particularly for students who experienced early academic failure. Keywords: Depression; School Dropout; Grade Retention; Risk Factor; Moderation Effect; Adolescent Development Introduction Adolescents who present combined symptoms of depression and school problems are among those facing the worst aca- demic outcomes (Roeser, Eccles, & Sameroff, 1998). Yet we know relatively little about the mechanisms implicating depres- sion in the course of school dropout. Although adolescents with mental health problems attain lower levels of education (Best, Hauser, Gralinski-Bakker, Allen, & Crowell, 2004; Kessler, Foster, Saunders, & Stang, 1995; Vander Stoep et al., 2000; Vander Stoep, Weiss, Kuo, Cheney, & Cohen, 2003), up until now most research on school dropout predictors has concen- trated on behavioral problems such as aggression, delinquency, or substance use (Janosz, Le Blanc, Boulerice, & Tremblay, 2000; Newcomb et al., 2002; Rumberger, 2011). Far less atten- tion has been devoted to problems like depression although one study reported that depression was predictive of school dropout (Vander Stoep, Weiss, McKnight, Beresford, & Cohen, 2002), others have shown its direct effect was small (Quiroga & Ja- nosz, 2008) or confounded by other factors (Fergusson & Woodward, 2002; Miech, Caspi, Moffitt, Wright, & Silva, 1999). These inconsistent findings are surprising considering the large body of knowledge indicating that depression often co-occurs with academic difficulties (Fleming et al., 2005; Stor- voll, Wichstrom, & Pape, 2003). The relationship between de- pression and grade retention (Asarnow et al., 2005; Fiske & Neuharth-Pritchett, 2007; Resnick et al., 1997), a serious risk factor of school dropout (Alexander, Entwisle, & Kabbani, 2001; Jimerson, Anderson, & Whipple, 2002; Pagani et al., 2008), is particularly noteworthy as it could help explain why children who face these issues are at increased risk for dropout. This study aims at understanding the relationship between de- pression and grade retention in the course of dropout Emotional distress and depression in adolescence are known to be associated with grade retention (Asarnow et al., 2005; Fiske & Neuharth-Pritchett, 2007; Resnick et al., 1997), one of the most important risk factors for school dropout. The effect of retention on dropout has been found to be very persistent and generally outweighing other risks (Alexander et al., 2001; Jim- erson et al., 2002; Pagani et al., 2008). Children and adoles- cents who have been held behind present multiple risk behav- iors, including emotional distress, that require a closer exami- nation (Resnick et al., 1997). For instance, grade retention com- monly coincides with special education, and among special needs students those with emotional problems are the most *This study was conducted as part of the thesis work of the first autho at the Department of Psychology and School Environment Research Group, University of Montreal.  C. V. QUIROGA ET AL. at-risk for dropping out (Wagner, 1995). It appears these stu- dents accumulate many risk factors (Blackorby, Cohorst, Garza, & Guzman, 2003; Krezmien, Leone, & Achilles, 2006; Reschly & Christenson, 2006) leading to academic disengagement and dropout (Roeser, Strobel, & Quihuis, 2002; Roeser, van der Wolf, & Strobel, 2001). They are also likely to experience the significant stigma and stress associated with school failure (An- derson, Jimerson, & Whipple, 2005). These early experiences may have a direct bearing on adolescent well-being as per- ceived school stress could influence adolescent emotional de- velopment and increase the risk for depression (Hankin, Mer- melstein, & Roesch, 2007). Depression can have damaging effects on adolescent social and cognitive functioning (Kovacs & Goldstone, 1991). De- clining concentration and attention for instance, can undermine academic achievement and increase the risk of school failure. This may pose an even greater threat to students with a history of grade retention who are already more susceptible to aca- demic difficulties. Thus, research suggests that depression may play a part in the school dropout process by precipitating drop- out for students who are more vulnerable to academic problems. One possibility that has yet to be investigated is whether the effect of depression on school dropout is independent from the effect of other risk factors, such as grade retention, or whether its effect is multiplicative, acting as a vulnerability factor that increases the risk associated with grade retention. This study aims to verify whether depression moderates the relationship between grade retention and school dropout after taking into account known risk factors of school dropout (i.e. academic competence, educational tracking, school rebellious- ness, etc.). As such, we expected depression to predict school dropout not only in itself, but by interacting with grade reten- tion. We hypothesized that depression in the seventh grade con- stitutes a vulnerability factor of dropout partly by aggravating the risk associated with earlier grade retention. Accounting for gender differences in depression, we also proposed an interac- tion between gender and depression considering boys greater emotional responsiveness to school-related problems (Rudolph, 2004) and girls higher sensitivity to interpersonal issues (Sund, Larsson, & Wichstrom, 2003). Further, an interaction between grade retention and gender was anticipated as studies have shown that being held behind is more frequent among boys (Byrd & Weitzman, 1994; Frey, 2005; Guèvremont, Roos, & Brownell, 2007; McCoy & Reynolds, 1999). Finally, we pro- posed a three-way interaction involving gender, grade retention and depression. Methods Participants This study draws on data from a high-risk longitudinal sam- ple (2000-2006) of French-speaking adolescents from Montreal (Quebec, Canada). Participants were recruited from two low-SES secondary schools. The schools were ranked by the Ministry of Education of Quebec (MEQ) in the three lowest deciles of SES based on maternal education and the proportion of unemployed parents. In 2000, students in seventh grade were invited to voluntarily participate in the study at the beginning of the school year. From an initial 602 students, we obtained pa- rental consent for 496 students (82.4%). Of these, we excluded 43 cases that failed to complete the depression inventories. We verified potential bias due to missing data by comparing the characteristics of respondents and non-respondents. There was a larger proportion of school dropouts among non-respondents compared to respondents, x2 (1) = 8.09, p < .01. No other dif- ference was found. The final sample comprised 453 participants. We followed this cohort during 6 years to identify participants who withdrew from school. Data Self-reported questionnaires were administered to partici- pants in class by trained research assistants three times during the seventh grade. Wave I occurred at the beginning of the school year, wave II was in February, and wave III was in May. Self-reported lifetime depression was measured at wave I, and seventh-grade depression at wave III. Unless otherwise speci- fied, control variables were measured at waves I, II, and III, and the results collected at each wave were averaged out to obtain a global score reflecting student experience in the seventh-grade. Gender and parental education were measured at wave I. Grade retention and school dropout status were obtained through MEQ’s registry. Measures Moderating Variable—Depression. Self-reported depression symptoms were measured with the French version of the In- ventory to Diagnose Depression (IDD; Pariente, Smith, & Gu- elfi, 1989; Zimmerman & Coryell, 1987a). This 22-item in- strument covers the main symptoms of depression according to DSM-IV-TR criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Each item is rated using a five-point scale from 0 to 4, denoting increasing severity. A threshold is applied on each symptom to determine clinical severity: a score of 0 indicates no distur- bance, a score of 1 indicates only subclinical severity, while a score ≥ 2 indicates clinical severity. Depression was determined when participant reported severe anhedonia or depressive mood, one symptom in at least four of the other symptom groups, and did not meet the criteria for bereavement, bipolar disorder, or depression-like health problems (e.g. thyroid dysfunction). No depression was coded 0 and depression was coded 1. The life- time IDD was administered at wave I to control for history of depression, and the annual IDD was used in wave III to assess the severity of depression symptoms in seventh grade. Al- though the retrospective nature of the IDD could introduce bias, studies have shown that recall of depression in childhood and adolescence is reliable (Masia et al., 2003). Both versions pre- sent remarkably strong psychometric properties (α = .90 to .92) across cultures and populations with adolescents and adults (Ackerson, Weigman Dick, Manson, & Baron, 1990; Ruggero, Johnson, & Cuellar, 2004; Sakado, Sato, Uehara, Sato, & Ka- meda, 1996). More specifically, IDD cases show a 91% con- vergence with Diagnostic Interview Schedule (Robins, Hlezer, Croughan, & Ratcliff, 1981), with a sensitivity of 74% and a specificity of 93% (Zimmerman & Coryell, 1987b). Our sample yielded Cronbach’s alphas ranging from .90 - .93. Focal Variable—Grade retention. We measured participant history of grade retention in primary school with two categories: never retained (0) and retained (1). Outcome Variable—Dropout Status. We followed partici- pants during six years, from the 7th grade until one year beyond expected graduation year, to determine their dropout status through the MEQ databank. The MEQ monitors student en- rollment across the province, including school transfers, voca- Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 750  C. V. QUIROGA ET AL. tional and adult education. We considered students who were continuously enrolled or had obtained secondary education certification as non-dropouts. Students who were not enrolled a particular year and had not obtained a diploma were considered as dropouts. Non-dropout was the reference group. Control Variables—Sociodemographic Variables. We con- trolled for gender and parental education. Parental education was measured by calculating the mean of mother and father educational attainment (1 = incomplete secondary education, 2 = completed secondary education, 3 = post-secondary enroll- ment, 4 = university enrollment) reported by participants. Academic Experience. Seventh-grade educational tracking had two categories: special education and general education. Student academic competence (LeBlanc, 1998) was measured with a 4-item Likert type scale (rated from 1 to 4) that was adapted in French from Skinner’s questionnaire (Skinner, 1995) and assesses self-perceived competency and control in school (α = .74). To assess student academic achievement we used the mean of self-reported performance in two basic subjects, Lan- guage arts and mathematic, on a scale ranging from 0 - 100. Socioemotiona l Problems. Self-reported anxiety was assessed with the French version of the Beck Anxiety Inventory (Beck & Steer, 1993; Freeston, Ladouceur, Thibodeau, Gagnon, & Rhé- aume, 1994). This 21-item instrument measures the main symp- toms of anxiety which are rated according to the degree of dis- turbance felt in the last seven days on a 4-point (0 to 3) Likert scale (α = .91). Student school rebelliousness (LeBlanc, 1998) was assessed with a 6-item scale measuring the frequency of self-reported misbehavior in school such as classroom disrup- tion, cheating on tests or truancy (α = .79). The answers (rang- ing from 0 to 3) were then recoded into two categories (0, and ≥1) and added up on a scale ranging from 0 to 6 reflecting the variety of inappropriate behavior. Friends school engagement (Le Blanc, 1998) was assessed with three items (rated on a 1 to 4 Likert-type scale) asking students to evaluate the attitudes of their closest friends toward school failure and dropout (α = .74). Student-teacher conflict was measured using the 7-item French adaptation (Fallu & Janosz, 2003) of Pianta’s Student-Teacher Relationship Scale (Pianta & Steinberg, 1992) (α = .85). This instrument asks participants to assess, on a 5-point Likert scale whether they experience conflict with their teachers. Statistical Analysis Data analysis began with the examination of correlations among study variables. The main hypotheses were tested with multivariate logistic regressions. Continuous predictors were standardized to facilitate the interpretation of odds ratios (OR) across variables. ORs can thus be interpreted as the expected change in outcome when the predictor changes by 1 standard deviation. For dichotomous predictors, the expected change in outcome is in comparison to the reference group. We first tested the simple effects of all predictors and then built multi- variate hierarchical models. Sociodemographic, academic ex- perience, socioemotional problems, lifetime and seventh-grade depression variables were entered first in the model, followed by grade retention. Next, two- and three-way interactions be- tween grade retention, depression, and gender were tested. Moderation is established when the interaction term contributes to the model over and above the main effects of the variables involved in the interaction (Hosmer & Lemeshow, 2000). The results reported are for the final model and include only statis- tically significant interactions. Results Table 1 shows the characteristics of the sample. The average age of participants was 12.53 years old (SD = .73), and 48% were female. Almost 16% of participants reported lifetime de- pression symptoms, and 13% reported depression symptoms in the seventh grade. There was a significant effect of gender for lifetime depression, x2 = 21.05 (1), p < .000, and for seventh grade depression, x2 = 11.25 (1), p < .001, with more girls re- porting depression symptoms at both times. Overall, 25% of students had a history of grade retention, 40% received special education, and 32% dropped out of school. Correlations among study variables are presented in Table 2. Unadjusted Effects Predicting Dropping Out Table 3 reports odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) of unadjusted effects for school dropout. The results show that students who repeated a grade in primary school were 4.40 times more likely to dropout of school than their counter- parts. Students in special education were 3.52 times more likely to dropout. As expected, depressed students in seventh grade were almost twice as likely to discontinue their education (OR = 1.97). School rebelliousness, friends’ school engagement, and student-teacher conflict were also significant risk factors of Table 1. Characteristics of participants. Characteristics All participants (n = 453) Age, mean (SD), y 12.53 (.73) Parental education, mean (SD) 2.2 (1.0) Gender, No. (%) Girls 215 (47.5) Boys 238 (52.5) Lifetime depression, No. (%) No depression 381 (84.1) Depression 72 (15.9) Seventh-grade depression, No. (%) No depression 394 (87.0) Depression 59 (13.0) Grade retention, No. (%) No retention 340 (75.1) Retention 113 (24.9) Educational tracking, No. (%) General education 274 (60.5) Special education 179 (39.5) Academic competence, mean (SD) 3.3 (.5) Academic achievement, mean (SD) 72.9 (8.8) Anxiety, mean (SD) 8.9 (8.3) School rebelliousness, mean (SD) 2.2 (1.5) Friends school engagement, mean (SD) 1.7 (.6) Student-teacher conflict, mean (SD) 2.3 (.9) Dropout, No. (%) No 308 (68.0) Yes 145 (32.0) Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 751  C. V. QUIROGA ET AL. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 752 Table 2. Correlations among variables in the study. Variables 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1. Parental education - 2. Educational tracking –.113* - 3. Grade retention –.104* .358*** - 4. Academic competence .100* –.198*** –.208*** - 5. Achievement .212*** –.265*** –.178*** .420*** - 6. Lifetime depression –0.04 –0.003 0.073 –.118* –.028 - 7. Seventh-grade depression –.071 0.051 .139** –.235*** –.102* .514*** - 8. Anxiety –.028 0.037 .129** –.210*** –.019 .451*** .511*** - 9. School rebelliousness –.139** .276*** .158** –.364*** –.368*** .223*** .290*** .236*** - 10. Friends school engagement .195*** –.314*** –.185*** .382*** .391*** -.094* –.157** –.113* –.496***- 11. Student-teacher conflict –.116* 0.001 0.003 –.264*** –.212*** .211*** .236*** .207*** .481*** –.339*** Note: ***p < .000. **p < .01. *p < .05. Table 3. Summary of simple and multiple logistic regression analysis for vari- ables predicting school dropout. Unadjusted Adjusteda Variable OR (95% CI) OR (95% CI) Parental education .73 (.59 - .90)* .87 (.68 - 1.10) Gender 1.22 (.82 - 1.81) .99 (.61 - 1.62) Educational tracking 3.52 (2.33 - 5.32)*** 1.78 (1.08 - 2.92)* Academic competence .63 (.51 - .77)*** .97 (.75 - 1.25) Achievement .57 (.46 - .71)*** .82 (.63 - 1.08) Anxiety 1.20 (.99 - 1.46) .91 (.70 - 1.18) School rebelliousness 1.98 (1.60 - 2.44)*** 1.46 (1.10 - 1.94)** Friends school engagement 2.07 (1.66 - 2.57)*** 1.45 (1.12 - 1.87)** Student-teacher conflict 1.40 (1.15 - 1.71)** 1.07 (.82 - 1.39) Lifetime depression .92 (.54 - 1.59) .62 (.31 - 1.26) Seventh-grade depression 1.97 (1.13 - 3.44)* 2.75 (1.18 - 6.42)* Grade retention 4.40 (2.81 - 6.90)*** 5.54 (2.46 - 12.46)*** Grade retention X seventhgrade depression 7.26 (1.46 - 36.17)* Note: aOdds ratios reported are for the final model with interaction and are ad- justed for all other variables included. ***p < .000. **p < .001. *p < .01. dropout. Parental education, academic competence, and achieve- ment on the other hand diminished the risk of dropping out. Gender, anxiety, and lifetime depression symptoms were not related to dropout. Adjusted Models Testing the Moderat ion Effect of Depression Adjusted ORs for the final model are also displayed in Table 3. The results show that students who had repeated a grade in primary school were 5.54 times more likely to be in the dropout group. Depression symptoms in the seventh grade were also associated with a 2.75 higher risk of dropping out with results indicating the likelihood of dropout for an adolescent reporting depression during the first year of secondary school could be as low as 1.18 or as high as 6.42 (according to 95% CI). Students receiving special education (OR = 1.78), showing rebellious behavior (OR = 1.46) or affiliating with academically disen- gaged peers (OR = 1.45) also presented a higher probability of dropping out of school. Parental education, gender, academic competence, achievement, anxiety, student-teacher conflict and lifetime depression symptoms did not significantly predict dropout when adjusting for other variables. Consistent with our hypothesis, there was a significant inter- action between grade retention and seventh-grade depression symptoms. The interaction term in the logistic regression equa- tion significantly improved the overall model, x2 = 6.84 (1), p < .00. The interaction confirmed that depression amplified the effect of the focal variable, grade retention, on school dropout. The likelihood of dropping out for students with a history of grade retention that also reported depression symptoms in sev- enth grade was 7.26 times higher than for those who did not report depression (Table 3). However, none of the two- or three-way interactions involving gender were significant. These additional effects were thus excluded from the final model. The chi-square for the final model was x2 = 112.4 (13), p < .000. Discussion We examined the moderating effect of seventh-grade depres- sion symptoms on the relation between grade retention and dropout up to six years later. Our results indicated that depres- sion is a vulnerability factor considerably aggravating the pre- existing risk of dropping out associated with early grade reten- tion. Previous studies have reported limited direct effect of depression on dropout (Fergusson & Woodward, 2002; Miech et al., 1999). However, focusing on the multiplicative relation between depression symptoms and grade retention yielded highly different results. It is essential, when studying vulner- ability (and protection) effects, to “unpack” the underlying processes that explain the relation between risk factors (Luthar, Sawyer, & Brown, 2006). Research has suggested a number of mechanisms through which grade retention and depression might become linked in the prediction of school dropout. It may be that children who face academic failure and grade retention feel confused about their situation and interpret grade retention as a punishment for their lack of success; they could also begin to doubt their own ability and give up on their schooling. This puts them at-risk of developing low self-perceived academic competence, decreased perseverance in academic tasks, and adolescent depression by the time they transition into secondary  C. V. QUIROGA ET AL. school (Cole, Martin, & Powers, 1997; Nolen-Hoeksema, Gir- gus, & Seligman, 1992). During adolescence, students who present multiple-risk factors, like school problems and emo- tional distress, are increasingly likely to face academic self- regulation problems (Roeser et al., 2002), helpless school be- havior (Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 1992) and academic disengage- ment (Roeser et al., 2001). According to Anderson (Anderson et al., 2005), as children transition into adolescence they become in- creasingly concerned about doing well in school. As such, they rate grade retention as one the most stressful life events they can experience. Coping with this stress is likely to present a serious challenge for depressed students who have been held behind, as they may feel stigmatized by teachers and peers, and experience social and cognitive impairment (Kovacs & Gold- stone, 1991) that could result in further academic failure. Thus the current findings are consistent with reports of depression symptoms in high-risk students undermining academic success and demonstrate its effect on school dropout. Academic Experience and Socioemotional Predictors of Dropout The third most important risk factor for dropping out in this high-risk sample was educational tracking. Others have re- ported that 30% of special education students leave school be- fore graduation, and when emotional disturbance is involved dropout nears 50% (Wagner, Kutash, Duchnowski, Epstein, & Sumi, 2005). Generally, special education students cumulate multiple risk factors for dropout, showing lower performance (Blackorby et al., 2003), motivation, academic engagement (Reschly & Christenson, 2006), and receiving more disciplinary sanctions (Krezmien et al., 2006) than those in the general population. Consistent with research on the role of behavior problems in early school leaving, school rebelliousness and friends’ school engagement also predicted dropout, indicating that adolescents who adhere to more deviant behavior are more likely to leave school without qualification (Loeber, Pardini, Stouthamer-Loeber, & Raine, 2007; Newcomb et al., 2002). Gender Differences The gap in the prevalence of depression between girls and boys did not translate into an incremental risk for dropout sug- gesting that gender differences are not involved in the complex relationship linking grade retention, depression and dropout. While it has been argued that boys are more reactive to school- related stressors (Rudolph, 2002), and girls exhibit more de- pression when facing interpersonal stressors (Sund et al., 2003), others have found no gender differences in reactivity to school stressors (Hankin et al., 2007; Shih, Eberhart, Hammen, & Brennan, 2006). Our findings are consistent with this and indi- cate that intervention for students with depression symptoms should target boys and girls equally. Implications for Research and Intervention This study demonstrates that depression symptoms play an important role in the process of dropping out of school for high-risk youth. Results underscore the necessity to integrate the study of mental health and schooling to promote positive development and improve intervention (Adelman & Taylor, 2010; Aviles, Anderson, & Davila, 2006; Becker & Luthar, 2002; Roeser et al., 1998). Prevention and intervention target- ing adolescents at-risk for depression would benefit both short-term mental health and long-term school perseverance. Yet, in the current context of school reform students’ emotional needs are seldom addressed. Instead most school-based inter- ventions focus on increasing academic performance or reducing problematic behavior (Becker & Luthar, 2002; Jimerson et al., 2006). Efforts to promote school success must include inter- ventions that target emotional wellbeing. This research also builds on a large body of knowledge showing the deleterious consequences of primary-school grade retention persist into late adolescence (Alexander et al., 2001; Jimerson et al., 2002; Pagani et al., 2008). The practical impli- cations of these findings for high-risk children and adolescents are very significant. Grade retention has often been used as the first type of intervention for children later diagnosed with learning difficulties or emotional disturbance (Barnett, Clarizio, & Payette, 1996; Mattison, 2000). The present results clearly show that this form of intervention, particularly when used among depressive youth, does not yield the expected benefits. Children that have been held back in grade should be thor- oughly screened for depression symptoms and provided appro- priate care when indicated. Limitations Limitations of this study should be mentioned. Our findings rely on a sample of adolescents from low-SES schools with a high rate of special education. Generalization is restricted to high-risk students. Future research should extend these results to the general population. We also had limited information about participant characteristics at the time of grade retention. To account for family SES, we adjusted for parental education, and can only presume that this had remained unchanged for most participants since grade retention. We also adjusted for participant prior history of depression. But other indicators of family and individual adversity could help understand the pre- sent results, such as family income, welfare, or learning dis- abilities. Despite these limitations, this study encompasses sev- eral strengths. It is based on a 6-year prospective design that allowed conclusions about the long-term impact of adolescent depression and academic experience on educational attainment. Whereas previous research on depression and dropout relied on observations in middle adolescence (Fergusson & Woodward, 2002; Miech et al., 1999), we investigated outcomes of depres- sion based on information gathered at 12-years-old thus shed- ding light on the consequences of early adolescent experience on schooling. Conclusion An important contribution of this study is to demonstrate adolescent depression symptoms’ strong relation to grade reten- tion in predicting school dropout. Depression proved to be a notable vulnerability factor during the adolescent transition considerably increasing the risk associated with grade retention in primary school. Implications for practice and policy are sig- nificant and point to the consequences of depression for high- risk adolescents and to the long-term effect associated with the practice of grade retention on dropout. Findings underscore the relevance of integrating the study of mental health and school- ing. Future studies should investigate processes that will im- prove our understanding of adolescent depression among high- risk students. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 753  C. V. QUIROGA ET AL. REFERENCES Ackerson, L. M., Weigman Dick, R., Manson, S. M., & Baron, A. E. (1990). Properties of the inventory to diagnose depression in Ameri- can Indian adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 29, 601-607. doi:10.1097/00004583-199007000-00014 Adelman, H. S., & Taylor, L. (2010). Mental health in schools: Engag- ing learners, preventing problems, and improving schools. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin. Alexander, K. L., Entwisle, D. R., & Kabbani, N. S. (2001). The drop- out process in life course perspective: Early risk factors at home and school. Teachers College Re c or d , 103, 760-822. doi:10.1097/00004583-199007000-00014 American Psychiatric Association (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing. Anderson, G. E., Jimerson, S. R., & Whipple, A. D. (2005). Student ratings of stressful experiences at home and school. Journal of Ap- plied School Psychology, 21, 1-20. doi:10.1300/J370v21n01_01 Asarnow, J. R., Jaycox, L. H., Duan, N., LaBorde, A. P., Rea, M. M., Tang, L., & Wells, K. B. (2005). Depression and role impairment among adolescents in primary care clinics. Journal of Adolescent Health, 37, 477-483. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.11.123 Aviles, A. M., Anderson, T. R., & Davila, E. R. (2006). Child and adolescent social-emotional development within the context of school. Child and Adolescent Mental Hea lth , 11, 32-39. doi:10.1111/j.1475-3588.2005.00365.x Barnett, K. P., Clarizio, H. F., & Payette, K. A. (1996). Grade retention among students with learning disabilities. Psychology in the Schools, 33, 285-293. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1520-6807(199610)33:4<285::AID-PITS3>3.0.C O;2-M Beck, A. T., & Steer, R. A. (1993). Beck anxiety inventory manual. New York, NY: The Psychological Corporation. Becker, B. E., & Luthar, S. S. (2002). Social-emotional factors affec- ing achievement outcomes among disadvantaged students: Closing the achievement gap. E du cat iona l Psychologist, 37, 197-214. doi:10.1207/S15326985EP3704_1 Best, K. M., Hauser, S. T., Gralinski-Bakker, J. H., Allen, J. P., & Cro- well, J. (2004). Adolescent psychiatric hospitalization and mortality, distress levels, and educational attainment: Follow-up after 11 and 20 years. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medici ne , 158, 749-752. doi:10.1001/archpedi.158.8.749 Blackorby, J., Cohorst, M., Garza, N., & Guzman, A.-M. The academic performance of secondary school students with disabilities. In: M. Wagner, C. Marder, J. Blackorby, R. Cameto, L. Newman, P. Levine, E. Davies-Mercier (Eds.) The achievements of youth with disabilities during secondary school. A report from the National Longitudinal Transition Study-2 (NLTS2). Menlo Park, CA: SRI International. Byrd, R. S., & Weitzman, M. L. (1994). Predictors of early grade reten- tion among children in the United States. Pediatrics, 93, 481-487. Cole, D. A., Martin, J. M., & Powers, B. (1997). A competency-based model of child depression: A longitudinal study of peer, parent, teacher, and self-evaluations. Journal of Child Psychology and Psy- chiatry, 38, 505-514. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01537.x Fallu, J.-S., & Janosz, M. (2003). La qualité des relations élèves-en- seignants à l'adolescence: Un facteur de protection de léchec scolaire. (The quality of teacher-student relationships in adolescence: A pro- tective factor of school failure). Revue de Psychoéd u ca t i on , 32, 7-29. Fergusson, D. M., & Woodward, L. J. (2002). Mental health, educa- tional, and social role outcomes of adolescents with depression. Ar- chives of General Psychiatry, 59, 225-231. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.59.3.225 Fiske, A. G., & Neuharth-Pritchett, S. (2007). Social functioning and depression of young adolescents who have been retained. The Ameri- can Educational Research Association (AERA) Annual Meeting, Chicago, April 2007. Fleming, C. B., Haggerty, K. P., Catalano, R. F., Harachi, T. W., Mazza, J. J., & Gruman, D. H. (2005). Do social and behavioral characteris- tics targeted by preventive interventions predict standardized test scores and grades? Journal of School He alth , 75, 342-349. Freeston, M. H., Ladouceur, R., Thibodeau, N., Gagnon, F., & Rhé- aume, J. (1994). L'inventaire d'anxiété de Beck: Propriétés psycho- métriques d'une traduction française (The Beck Anxiety Inventory: Psychometric properties of a French translation). L'Encéphale, 3, 13- 27. Frey, N. (2005). Retention, social promotion, and academic redshirting: What do we know and need to know? Remedial and Special Educa- tion, 26, 332-346. doi:10.1177/07419325050260060401 Guèvremont, A., Roos, N., & Brownell, M. (2007). Predictors and consequences of grade retention: Examining data from Manitoba, Canada. Canadian Journal of School Psychology, 22, 50-67. doi:10.1177/0829573507301038 Hankin, B. L., Mermelstein, R., & Roesch, L. (2007). Sex differences in adolescent depression: Stress exposure and reactivity models. Child Development, 78 , 279-295. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.00997.x Hosmer, D. W., & Lemeshow, S. (2000). Applied logistic regression (2nd ed.). New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons. doi:10.1002/0471722146 Janosz, M., Le Blanc, M., Boulerice, B., & Tremblay, R. E. (2000). Predicting different types of school dropouts: A typological approach with two longitudinal samples. Journal of Educational Psychology, 92, 171-190. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.92.1.171 Jimerson, S. R., Anderson, G. E., & Whipple, A. D. (2002). Winning the battle and losing the war: Examining the relation between grade retention and dropping out of high school. Psychology in the Schools, 39, 441-457. doi:10.1002/pits.10046 Jimerson, S. R., Pletcher, S. M., Graydon, K., Schnurr, B. L., Nickerson, A. B., & Kundert, D. K. (2006). Beyond grade retention and social promotion: Promoting the social and academic competence of stu- dents. Psychology in the Schoo ls , 43, 85-97. doi:10.1002/pits.20132 Kessler, R. C., Foster, C. L., Saunders, W. B., & Stang, P. E. (1995). Social consequences of psychiatric disorders, I: Educational attain- ment. American Journal of Psychiatry, 152, 1026-1032. Kovacs, M., & Goldstone, D. (1991). Cognitive and social cognitive development of depressed children and adolescents. Journal for the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 30, 388-392. doi:10.1097/00004583-199105000-00006 Krezmien, M. P., Leone, P. E., & Achilles, G. M. (2006). Suspension, race, and disability: Analysis of statewide practices and reporting. Journal of Emotional and Be h avi oral Disorders, 14, 217-226. doi:10.1177/10634266060140040501 LeBlanc, M. (1998). Manuel sur des mesures de l'adaptation sociale et personnelle pour les adolescents québécois, 3e édition (Manual on measures of social and personal adjustment for Quebec adolescents, 3rd edition). Québec: Université de Montréal, École de Psychoédu- cation, Groupe de Recherche sur les Adolescents en Difficulté. Loeber, R., Pardini, D. A., Stouthamer-Loeber, M., & Raine, A. (2007). Do cognitive, physiological, and psychosocial risk and promotive factors predict desistance from delinquency in males? Development and Psychopathology, 19, 867-887. doi:10.1017/S0954579407000429 Luthar, S. S., Sawyer, J. A., & Brown, P. J. (2006). Conceptual issues in studies of resilience: Past, present, and future research. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences , 1094, 105-115. doi:10.1196/annals.1376.009 Masia, C. L., Storch, E. A., Dent, H. C., Adams, P., Verdeli, H., Davies, M., & Weissman, M. M. (2003). Recall of childhood psychopathol- ogy more than 10 years later. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 42, 6-12. doi:10.1097/00004583-200301000-00005 Mattison, R. E. (2000). School consultation: A review of research on issues unique to school environment. Journal for the American Academy of child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 39, 402-413. doi:10.1097/00004583-200004000-00008 McCoy, A. R., & Reynolds, A. J. (1999). Grade retention and school performance: An extended investigation. Journal of School Psychol- ogy, 37, 273-298. doi:10.1016/S0022-4405(99)00012-6 Miech, R. A., Caspi, A., Moffitt, T. E., Wright, B. R. E., & Silva, P. A. (1999). Low socioeconomic status and mental disorders: A longitu- Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 754  C. V. QUIROGA ET AL. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 755 dinal study of selection and causation during young adulthood. American Journal of Sociology, 104, 1096-1131. doi:10.1086/210137 Newcomb, M. D., Abbott, R. D., Catalano, R. F., Hawkins, J. D., Bat- tin-Pearson, S., & Hill, K. (2002). Mediational and deviance theories of late high school failure: Process roles of structural strains, aca- demic competence, and general versus specific problem behavior. Journal of Counseling Psyc holo gy, 49, 172-186. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.49.2.172 Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Girgus, J. S., & Seligman, M. E. P. (1992). Pre- dictors and consequences of childhood depressive symptoms: A 5- year longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 101, 405- 422. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.101.3.405 Pagani, L. S., Vitaro, F., Tremblay, R. E., McDuff, P., Japel, C., & Larose, S. (2008). When predictions fail: The case of unexpected pathways toward high school graduation. Journal of Social Issues, 64, 175-193. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.2008.00554.x Pariente, P., Smith, M., & Guelfi, J.-D. (1989). Un questionnaire pour le diagnostic d'épisode dépressif majeur: L'inventaire pour le diag- nostic de la dépression (IDD). Présentation de la version française. (A questionnaire to diagnose major depressive episode: The inven- tory to diagnose depression. Presentation of the French version). Psy- chiatrie et Psychobiologie, 4, 375-385. Pianta, R. C., & Steinberg, M. (1992). Teacher-child relationships and the process of adjusting to school. New Directions for Child Devel- opment, 1992, 61-80. doi:10.1002/cd.23219925706 Quiroga, C., & Janosz, M. (2008). Identifying the mediating processes linking adolescent depression to school dropout: The role of aca- demic competency and control. The 12th Biennial Meeting of the So- ciety for Research on Adolescence (SRA), Chicago, 5-9 March 2008. Reschly, A., & Christenson, S. L. (2006). Prediction of dropout among students with mild disabilities: A case for the inclusion of student engagement variables. Remedial and Special Education, 27 , 276-292. doi:10.1177/07419325060270050301 Resnick, M. D., Bearman, P. S., Blum, R. W., Bauman, K. E., Harris, K. M., Jones, J., & Udry, J. R. (1997). Protecting adolescents from harm. Findings from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health. The Journal of the American Medi ca l Asso c ia t io n , 278, 823-832. doi:10.1001/jama.1997.03550100049038 Robins, L. N., Hlezer, J. E., Croughan, J., & Ratcliff, K. S. (1981). National institute of mental health diagnostic interview schedule: Its history, characteristics, and validity. Archives of General Pscyhiatry, 38, 381-389. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1981.01780290015001 Roeser, R. W., Eccles, J. S., & Sameroff, A. J. (1998). Academic and emotional functioning in early adolescence: Longitudinal relations, patterns, and prediction by experience in middle school. Develop- ment and Psychopathology, 10, 321-352. doi:10.1017/S0954579498001631 Roeser, R. W., Strobel, K. R., & Quihuis, G. (2002). Studying early adolescents’ academic motivation, social-emotional functioning and engagement in learning: Variable- and person-centered approaches. Anxiety, Stress & Coping, 15, 345-368. doi:10.1080/1061580021000056519 Roeser, R. W., van der Wolf, K., & Strobel, K. R. (2001). On the rela- tion between social-emotional and school functioning during early adolescence: Preliminary findings from Dutch and American samples. Journal of School Psychology, 39, 111-139. doi:10.1016/S0022-4405(01)00060-7 Rudolph, K. D. (2002). Gender differences in emotional responses to interpersonal stress during adolescence. Journal of Adolescent Health, 30, 3-13. Rudolph, K. D. (2004). A self-regulation approach to understanding adolescent depression in the school context. In T. Urdan, & F. Paja- res (Eds.), Educating adolescents: Challenges and strategies (pp. 33- 64). Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishing. Ruggero, C. J., Johnson, S. L., & Cuellar, A. K. (2004). Spanish-lan- guage measures of mania and Depression. Psychological Assessment, 16, 381-385. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.16.4.381 Rumberger, R. W. (2011). Dropping out: Why students drop out of high school and what can be done about it. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. doi:10.4159/harvard.9780674063167 Sakado, K., Sato, T., Uehara, T., Sato, S., & Kameda, K. (1996). Dis- criminant validity of the inventory to diagnose depression, lifetime version. Acta P syc hiatrica Scandinavica, 93, 257-260. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.1996.tb10644.x Shih, J. H., Eberhart, N. K., Hammen, C. L., & Brennan, P. A. (2006). Differential exposure and reactivity to interpersonal stress predict sex differences in adolescent depression. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 35 , 103-115. doi:10.1207/s15374424jccp3501_9 Skinner, E. A. (1995). Perceived Control, motivation, and coping. Thou- sand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. Storvoll, E. E., Wichstrom, L., & Pape, H. (2003). Gender differences in the association between conduct problems and other problems among adolescents. Journal of Scandinavian Studies in Criminology and Crime Prevention, 3, 194-209. doi:10.1080/14043850310010794 Sund, A. M., Larsson, B., & Wichstrom, L. (2003). Psychosocial corre- lates of depressive symptoms among 12-14-year-old Norwegian ado- lescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 44, 588-597. doi:10.1111/1469-7610.00147 Vander Stoep, A., Beresford, S. A., Weiss, N. S., McKnight, B., Cauce, A. M., & Cohen, P. (2000). Community-based study of the transition to adulthood for adolescents with psychiatric disorder. American Journal of Epidemiology, 152, 352-362. doi:10.1093/aje/152.4.352 Vander Stoep, A., Weiss, N. S., Kuo, E. S., Cheney, D., & Cohen, P. (2003). What proportion of failure to complete secondary school in the US population is attributable to adolescent psychiatric disorder? Journal of Behavioral H e a l th S e r v i c e s & Research, 30, 119-124. doi:10.1007/BF02287817 Vander Stoep, A., Weiss, N. S., McKnight, B., Beresford, S. A. A., & Cohen, P. (2002). Which measure of adolescent psychiatric disor- der—diagnosis, number of symptoms, or adaptive functioning—best predicts adverse young adult outcomes? Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 56, 56-65. doi:10.1136/jech.56.1.56 Wagner, M. (1995). Outcomes for youths with serious emotional distur- bance in secondary school and early adulthood. The Future of Chil- dren, 5, 90-112. doi:10.2307/1602359 Wagner, M., Kutash, K., Duchnowski, A. J., Epstein, M. H., & Sumi, C. W. (2005). The children and youth we serve: A national picture of the characteristics of students with emotional disturbances receiving special education. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 13, 79-96. doi:10.1177/10634266050130020201 Zimmerman, M., & Coryell, W. (1987a). The Inventory to Diagnose Depression (IDD): A self-report scale to diagnose major depressive disorder. Journal of Consulting a nd Clinical Psychology, 55, 55-59. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.55.1.55 Zimmerman, M., & Coryell, W. (1987b). The Inventory to Diagnose Depression, lifetime version. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 75, 495-499. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.1987.tb02824.x

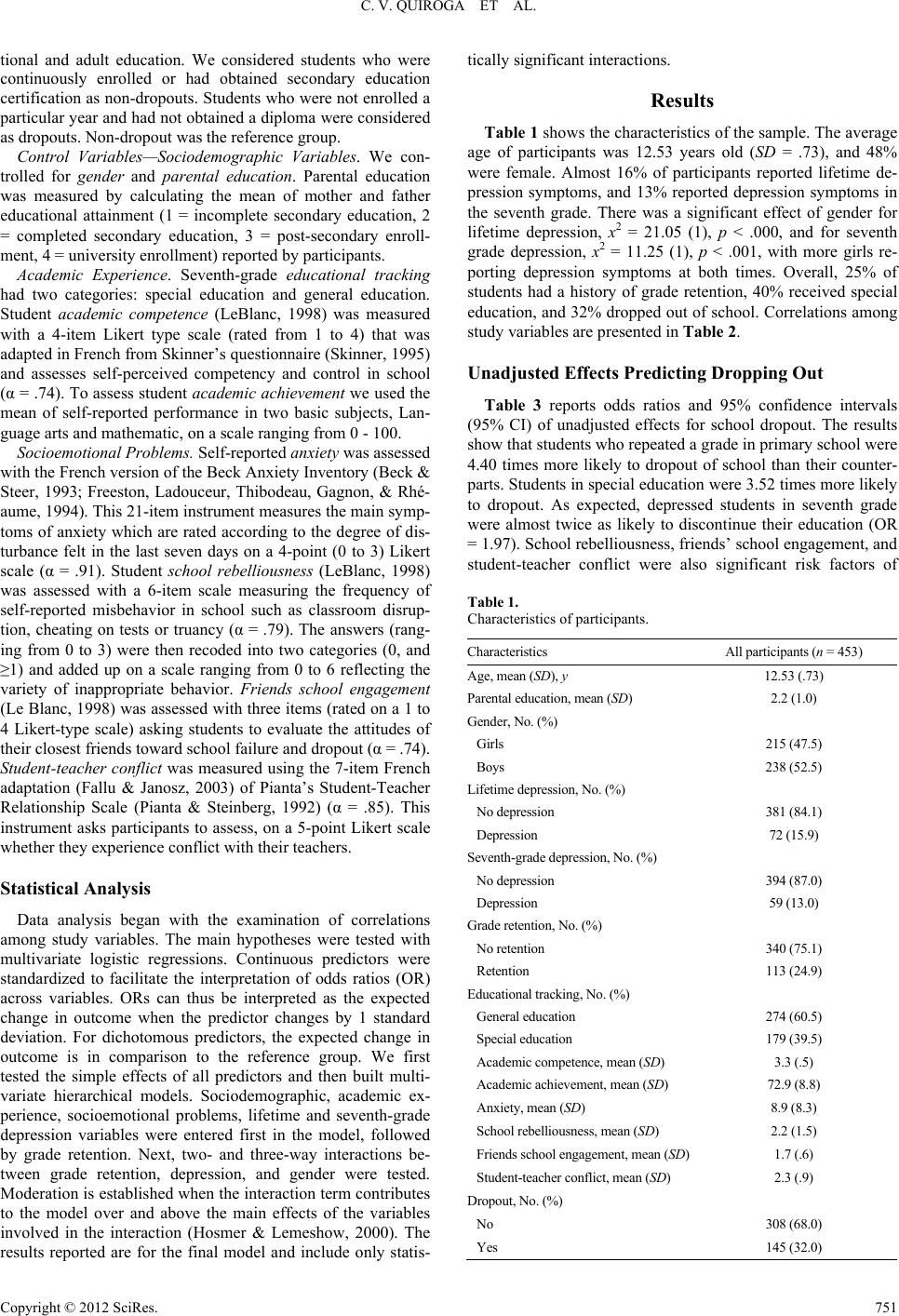

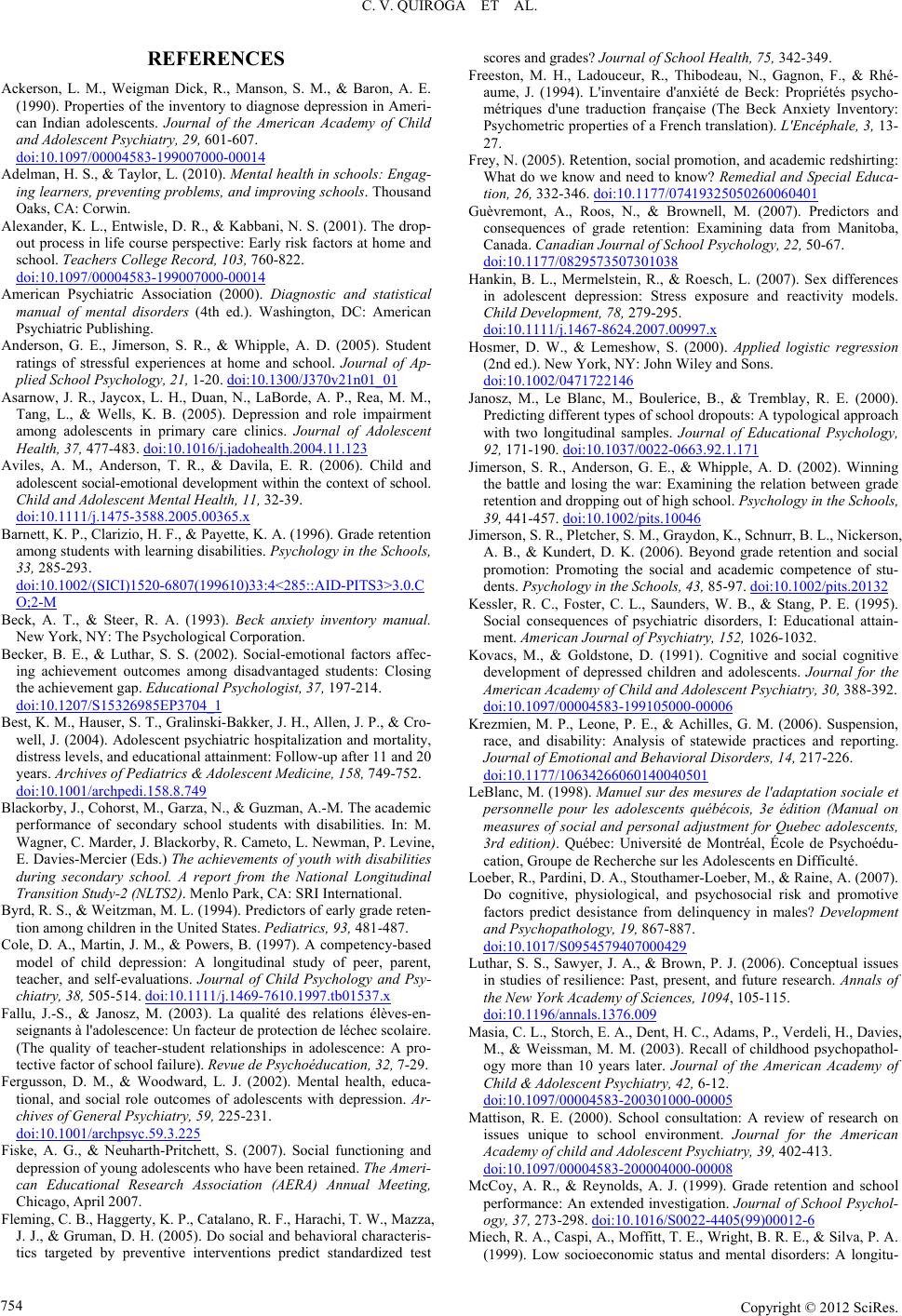

|