Psychology 2012. Vol.3, No.9, 675-680 Published Online September 2012 in SciRes (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/psych) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/psych.2012.39102 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 675 Affect Consciousness and Adult Attachment Börje Lech1*, Gerhard Andersson2,3, Rolf Holmqvist1 1Department of Behavioural Sciences and Learning, Linköping University, Linköping, Sweden 2Department of Behavioural Sciences and Learning, Swedish Institute for Disability Research, Linköping University, Linköping, Sweden 3Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Psychiatry Section, Karolinska Institutet, Solna, Sweden Email: *borje.lech@.liu.se Received February 22nd, 2012; revised May 8th, 2012; accepted July 2nd, 2012 The concept of affect consciousness refers to the ability to perceive, reflect upon, express and respond to one’s own or other individuals’ affective experiences. The aim of this study was to investigate how affect consciousness and adult attachment are related. Three clinical groups (eating disorders, relational prob- lems, and stress-related problems), and one non-clinical group (total N = 82) completed the Attachment Style Questionnaire and were interviewed using the Affect Consciousness Interview—Self/Other. Results showed associations between high affect consciousness and secure attachment, and between low affect consciousness and insecure attachment. Moreover, attachment style was predicted by consciousness about others’ and own affects in general, and specifically by consciousness about others’ anger and guilt, and by own joy. Affect consciousness as a potential dimension or moderator of attachment merits further inves- tigation. Keywords: Affect; Affect Consciousness; Affect Consciousness Interview—Self/Other; ACI-S/O Attachment Style; ASQ; Emotion Introduction To consciously perceive, reflect on, express and respond to one’s own or other individuals’ affect experiences is most likely beneficial for mental health and for how well interper- sonal relationships are handled. A proposed joint label for these abilities is Affect Consciousness (Monsen, Eilertsen, Melgård, & Ödegård, 1996; Lech, Andersson, & Holmqvist, 2008). Af- fect consciousness focuses on affects as organizers of self- experience and interpersonal interactions. Lech et al. (2008) found that consciousness about own and others’ affects, assessed in a semi-structured interview, was associated with organization of self-experience (i.e., self-image) as well as with conceptions of social interaction, and reports of psychological distress. Another concept that has been associated with the regulation of affects, and which has been applied in the study of interper- sonal interaction and self-experience, is that of attachment (Feeney, Noller, & Roberts, 1998). Although based on a theory about the early development of human beings (Bowlby, 1969), attachment has been postulated to have implications for adult intimate relationships and self-understanding (Bowlby, 1969; Fonagy, 2001). Connected with attachment, the concept of mentalization, implying the capacity to understand the com- plexity of one’s own and others’ thoughts, intentions and af- fects, has been described as a core aspect of adult attachment (Bochard, Target, Lecours, Fonagy, Tremblay, Schater, & Stein, 2008; Eagle, 1997; Fonagy, 2001; Fonagy, Gergely, Jurist, & Target, 2004; Fonagy & Target, 1998). The relationship between the concepts of mentalization and affect consciousness (Monsen et al., 1996) has been theoretic- cally outlined by Mohaupt, Holgersen, Binder and Nielsen (2006) and Choi-Kain and Gunderson (2008). The latter authors suggest that the concepts of affect consciousness and mentali- zation partly overlap. Using the concept mentalized affectivity (Fonagy et al., 2002), they argue that affect consciousness con- tributes to the regulation of affects, which leads to better capa- city to develop a mentalizing stance towards affects. However, Choi-Kain and Gunderson (2008) also argue that affect con- sciousness focus more than mentalization on the explicit, con- scious awareness and expression of affect states. Mohaupt et al. (2006) also argue that there are great similarities between the concepts, but that they differ in some respects. One difference is that mentalization theory argues that affects are seen as de- veloping in a relationship, primarily between the mother and the infant, whereas the main focus of the affect consciousness concept is the individuals’ perception and organization of his or her own affects. In order to encompass the interactional aspect of affect con- sciousness, Lech et al. (2008) reconceptualized the concept of affect consciousness to also capture the individual’s capacity to consciously perceive, reflect on, and express or respond to af- fect displays in other individuals. This new conceptualization of affect consciousness thus comprises the original instrument used to assess affect consciousness (Affect Consciousness In- terview; Monsen et al., 1996) as well as questions intended to capture the subject’s consciousness about others’ affects. This addition of consciousness about others’ affects has the potential to bring the concept of affect consciousness closer to the con- cept of mentalization. Two different principal ways to measure adult attachment have emerged. One is primarily based in developmental psy- chology and uses a semi-structured interview, the Adult At- tachment Interview (AAI; George, Kaplan, & Main, 1985), to rate attachment patterns by studying the individual’s ways of describing their relationships with important persons in their *Corresponding author.  B. LECH ET AL. life history (George et al., 1985). The other perspective mainly utilizes self-report questionnaires to measure adult attachment. This perspective mainly focuses on how attachment is repre- sented in the content of thoughts and feelings. Despite their common theoretical roots, the relations between the AAI and self-rated attachment scales seem to be weak and the two tradi- tions seem to measure and describe two different phenomena (Roisman et al., 2007; Riggs, Paulson, Tunnell, Sahl, Atkison, & Ross, 2007). Results on the AAI have been found to be con- sistently associated with childhood attachment experiences (Fraley, 2002), as measured by the Strange Situation procedure (Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall, 1978). On the contrary, scores on self-report questionnaires of adult attachment have been less strongly related to childhood attachment experiences as measured by the Strange Situation procedure (Fraley, 2002). Methodological differences (e.g., interview versus self-report) can at least partly explain the discrepancy between AAI and self-report questionnaires. On the other hand, self-report ques- tionnaires seem to capture basic personality traits and some aspects of adult functioning that are theoretically meaningful in attachment theory, such as the self-evaluated capacity for adult intimate or romantic relationships (Roisman et al., 2007), social support and emotional status (Barry, Lakey, & Orehek, 2007) and strategies of emotion regulation (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2005; Woodhouse & Gelso, 2008). Different styles of self-rated attachment seem to be related to emotions in rather distinct ways. The results from a study by Searle and Meara (1999) showed that emotional expressivity, attention and intensity distinguished different attachment groups. In a review by Mikulincer and Shaver (2005), the con- clusion was that securely attached individuals displayed more differentiated emotions than insecurely attached individuals, and that they used them in a more beneficent and less defensive way. Barry et al. (2007) found that perceived social support, high levels of negative affects and low levels of positive affects were linked to insecure attachment. A study by Woodhouse and Gelso (2008) indicated that higher levels of attachment anxiety were associated with regulation of negative affect within the first session of therapy. Hence, and in line with Roisman et al. (2007), we will regard self-rated adult attachment as a variable of interest despite its loose connection with childhood attachment and AAI. Accord- ing to Feeney, Noller and Hanrahan (1994), self-assessed se- cure attachment as measured by the Attachment Style Ques- tionnaire (ASQ; Feeney et al., 1994) implies that the person has high self-esteem. Briefly, attachment theory predicts that per- sons who have high scores on the ASQ are confident about relationships and have an ability to be both close and separate from other important persons without being worried or anxious. Closeness is enjoyable and they see relations as important. The attachment style that is labeled avoidant implies that the person is worried about people getting too close. High scores on avoi- dant attachment style value achievement more than relation- ships and are uncomfortable with closeness. Persons with self- rated anxious attachment styles are characterized by contradict- tory feelings about relationships. They need approval from others and are therefore preoccupied with their relationships; they eagerly want closeness but are at the same time not com- fortable with it. Moreover, they lack confidence in themselves and others. These predictions have received empirical support (Belsky & Cassidy, 1994). The present study focused on the relation between affect consciousness and self-reported attachment. No previous study appears to have analyzed this link. In the present study, we study associations between self-rated attachment patterns and the ability to be conscious about own and others’ affects. The latter ability was measured in a structured interview (Monsen et al., 1996; Lech et al., 2008). In addition, we analyzed whether or not self-rated attachment could be predicted from the results of the structured affect consciousness interview which had a focus on both consciousness about own and consciousness about others’ affects. It was hypothesized that affect con- sciousness would be associated with the self-rated attachment patterns, with higher levels of affect consciousness being asso- ciated with secure attachment and lower levels with insecure attachment. Method Participants and Procedure In order to have a wide range of participants amongst whom attachment patterns and levels of affect consciousness could be expected to differ, women with and without known clinical problems were included in the study. A heterogeneous sample was therefore recruited in clinical contexts and from the com- munity. There were 48 women with eating disorders (e.g., bu- limia and anorexia), eleven with severe relational problems (i.e., under care for not being able to manage their child or their children), and ten with stress related problems (e.g., burnout and on long-term sick leave). Finally, we included thirteen women without any known psychiatric or relational problems. The mean age of the total sample was 29 years (SD = 10.37; range 15 to 62). There were no significant age differences be- tween the subgroups. All participants provided informed consent. Before being in- terviewed with the Affect Consciousness Interview—Self/Other (ACI-S/O) the participants were given a self-report inventory, the Attachment Style Questionnaire (ASQ; Feeney et al., 1994). Measures The Affect Consciousness Interview—Self/Other (ACI-S/O) is a semi-structured interview in which the interviewer asks about seven affects: interest/excitement, enjoyment/joy, fear/ panic, anger/rage, humiliation/shame, sadness/despair and guilt/remorse (Lech et al., 2008). The answers are scored on a scale from 1 to 10 points on each of eight dimensions of con- sciousness, where 10 is the highest possible degree of affect consciousness. The eight dimensions of affect consciousness are: a) Awareness of the individual’s own affects: how does the subject recognize the affects? b) Tolerance of the individual’s own affects: to what extent does the subject let the affects im- pact upon him or her? c) Non-verbal expression of the affects: how does the person express his or her affective reactions non- verbally in different interpersonal settings? d) Verbal expres- sion of the affects: how does the subject tell others in different situations about his or her affective reactions? e) Awareness of others’ affective reaction: how does the subject notice or recog- nize others’ affective reactions? f) Tolerance of others’ affect- tive reactions: to what extent does the subject let the affect of others impact upon him or her? g) Non-verbal: how does the person respond to others’ affective reactions non-verbally in different interpersonal settings? h) Verbal response to others’ affective reaction: how does the subject verbally respond to Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 676  B. LECH ET AL. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 677 others’ affective reactions in different situations? Nine raters were used, with at least two raters for each of the 82 interviews. Six raters were psychology students and three were graduates and experienced psychologists. Eight raters also performed interviews. They were all trained both in the proce- dure of interviewing and of rating the interview. Interrater reli- ability for ACI-S/O (both own and others’ affects) as assessed with intraclass correlation (ICC) has been found to be 0.95 (Lech et al., 2008). Attachment was measured with the Attachment Style Ques- tionnaire (ASQ; Feeney et al., 1994), which has been translated into Swedish (ASQ-sw; Håkansson & Tengström, 1996) and contains 40 items. The ASQ is intended to measure dimensions central to adult attachment, including different styles or patterns of attachment. Moreover, the ASQ has been designed to be suitable for both young adolescents as well as older individuals without a requirement of prior experience of romantic relation- ships. The questions in ASQ can be analyzed in two separate factors (secure and insecure attachment), but can also be ana- lyzed on the basis of a three factor structure in line with Hazan’s and Shavers’ (1987) conceptualization of attachment (e.g., secure, avoidant, and anxious). Feeney et al. (1994) re- ported internal consistencies for the English version and found adequate Cronbach alphas for the subscales Security (0.83), Avoidance (0.83), and Anxiety (0.85). The test-retest reliability over a period of approximately ten weeks was 0.74, 0.75 and 0.80 for the three subscales. The internal consistency for the three subscales in the Swedish version is in the same range as for the English original version (Håkanson & Tengström, 1996). Results Descriptive Statistics and Correlations Means, standard deviations and significant group differences on the ASQ and ACI-S/O are presented in Table 1. The results in Table 1 show that individuals in the non- clinical group had significantly higher ratings of secure attach- ment and that those in the patient groups had significantly higher levels of insecure attachment. The table also shows that the individuals in the non-clinical group had significantly higher ratings than the patient group of consciousness about own and others’ affects irrespectively of which specific affect they were interviewed about. Table 2 shows the correlations between the affect ratings and scores on the three subscales of the Attachment Style Ques- tionnaire (ASQ). The results in Table 2 show significant correlations between almost all scores on ACI-S/O and the scores on the ASQ scales. The exception was consciousness about own guilt which did not correlate with any of the ASQ subscales. Moreover, con- sciousness about others’ guilt did not correlate significantly with the avoidant attachment scale. All the significant correla- tions between affect consciousness and the secure attachment Table 1. Descriptive statistics for the three subscales of the attachment style questionnaire and rating of the consciousness about specific own and others’ af- fects in the affect consciousness interview—self/other in the clinical (N = 69) and the non clinical (N = 13) groups. Clinical group Non clinical group ASQ M SD M SD t-value significance Secure 3.30 1.15 4.91 0.70 4.86 p < 0.001 Avoidant 3.44 0.65 2.41 0.88 5.38 p < 0.001 Anxious 4.40 0.88 2.85 0.71 6.01 p < 0.001 ACI-S/O Own Interest 4.77 0.99 6.89 1.41 6.59 p < 0.001 Joy 4.94 0,95 7.27 1.08 7.88 p < 0.001 Fear 4.24 0.89 5.84 1.26 5.50 p < 0.001 Anger 4.14 0.88 6.08 1.33 6.66 p < 0.001 Shame 3.47 0.83 4.76 1.50 4.44 p < 0.001 Sadness 3.95 0.92 5.91 1.09 6.85 p < 0.001 Guilt 3.53 0.83 4.31 1.92 2.39 p < 0.05 Others’ Interest 4.46 1.07 6.49 1.27 6.13 p < 0.001 Joy 4.63 0.79 6.55 1.19 7.37 p < 0.001 Fear 4.17 1.15 5.93 1.28 5.00 p < 0.001 Anger 4.02 0.78 5.71 1.16 6.60 p < 0.001 Shame 3.61 1.23 4.86 1.55 3.22 p < 0.01 Sadness 4.42 0.91 6.37 0.96 7.04 p < 0.001 Guilt 3.36 1.17 4.93 1.10 4.47 p < 0.001  B. LECH ET AL. Table 2. Correlations between ACI-S/O and ASQ scores (N = 82). ACI-S/O ASQ Consciousness Secure Avoidant Anxious About attachment attachment attachment Own Interest 0.41** –0.41** –0.41** Joy 0.46** –0.44** –0.48** Fear 0.42** –0.47** –0.33** Anger 0.43** –0.41** –0.38** Shame 0.30** –0.31** –0.26* Sadness 0.30** –0.42** –0.31** Guilt 0.08 0.00 –0.07 Others’ Interest 0.27* –0.28* –0.37** Joy 0.38** –0.38** –0.44** Fear 0.40** –0.32** –0.31** Anger 0.53** –0.53** –0.50** Shame 0.29** –0.23* –0.22* Sadness 0.47** –0.46** –0.46** Guilt 0.28* –0.12 –0.24* Note: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01. scale were positive and all the significant correlations between affect consciousness and the avoidant and anxious attachment scales were negative. Regression Analyses Consciousness about own and others’ affects was used in multiple regression analyses in order to analyze its contribution to the three different ASQ subscales. The analyses were made separately for consciousness about own and about others’ af- fects. First, the subscale measuring secure attachment was used as a dependent variable. The regression for consciousness about own affects was significant [F(7,73) = 4.2, , p < 0.001], but there was no significant contribution from any sin- gle affect. The regression for consciousness about others’ af- fects was also significant [F(7,73) = 6.3, , p < 0.0001]. There was a significant contribution from conscious- ness of others’ anger (β = 0.39, p < 0.01). 2 adj. R0.2 2 adj. R0.3 2 2 4 8 Secondly we analyzed the results for avoidant attachment. The regression using all the seven own affects as independent variables was significant [F(7,73) = 4.7, , p < 0.0001], but there was no significant contribution from any single affect. The regression using the seven others’ affects was also significant [F(7,73) = 6.6, , p < 0.0001], and there was a significant contribution from consciousness of oth- ers’ anger (β = –0.49, p < 0.001), and others’ guilt (β = 0.32, p < 0.01). 2 adj. R0.2 .33 2 adj. R0 Finally, the subscale measuring anxious attachment was analyzed. The regression for the seven own affects was signifi- cant [F(7,73) = 3.5, , p < 0.01], and there was one significant contribution by own joy (β = 0.35, p < 0.05). The re- gression for the seven others’ affects was also significant [F(7,73) = 5.0, 2 adj. R0.1 2 adj. R , p < 0.0001], and there was a sig- nificant contribution from consciousness of others’ anger (β = –0.34, p < 0.05). Discussion The aim of this study was to analyze if affect consciousness, as assessed in a structured interview, was associated with self-rated adult attachment patterns. It was hypothesized that there would be associations between high affect consciousness and secure attachment, and between low affect consciousness and insecure attachment. This prediction was confirmed. We also wanted to explore whether consciousness about own and others’ affects, on both a global and an affect-specific level, were predictive of different patterns of self-rated adult attach- ment. Here the results were less straightforward, but interesting associations emerged. Significant differences in self-reported attachment style were found between the clinical group and the non-clinical group. The clinical group had significantly higher levels of insecure attachment and the non-clinical group had significantly higher levels of secure attachment. The non-clinical group also had significantly higher consciousness about own and others’ af- fects than the patient group regardless of which single affect they were interviewed about. This was in line with our expecta- tions. As mentioned, the results also showed several significant correlations between affect consciousness and the three attach- ment patterns. Secure attachment was associated with all the affects except for guilt, and the insecure attachment patterns were associated with the same variables but in the opposite direction. This is in line with the earlier reported finding by Barry et al. (2007) in which high negative affects and low posi- tive affects were found to be linked to insecure attachment. The results can also be interpreted in light of the review by Miku- lincer and Shaver (2005), where one implication is that securely attached persons have more conscious means of access to their affects than insecurely attached persons. Regression analyses showed that there were significant con- tributions from both consciousness of own and others’ affects to the variance in the different attachment styles. The contribu- tion from consciousness about others’ affects appeared some- what higher than the contribution from consciousness about own affects. In addition to the contribution from the over-all consciousness of affects, some single categorical affects inde- pendently contributed to the variance in attachment ratings. Joy was the only single own affect which contributed by itself to any of the attachment variants (to anxious attachment). Con- sciousness about others’ guilt contributed significantly to the variance in avoidant attachment style and consciousness about others’ anger contributed significantly to the variance in all attachment styles. Consciousness about others’ affects, and especially others’ anger apparently had special importance for the variation in self-assessed attachment style. Consciousness about others’ guilt also contributed significantly to the variance in avoidant attachment style, and in a similar manner consciousness about own joy explained variance in the scores relating to anxious attachment. To be less able to manage own joy seems to con- tribute to an anxious attachment style and to be more able to manage others’ guilt seems to contribute to an avoidant attach- ment style. In other words, to be able to to express and experi- Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 678  B. LECH ET AL. ence own joy but not notice and act in response to others’ guilt seems to be useful as it protects against an insecure attachment style. One way to interpret these findings is that if a person is not able to perceive, tolerate and/or express their joyful affects, then a preoccupation with the other person, and perhaps espe- cially the other persons feeling of guilt in the relationship can ensue in a need for approval from the other. If a person is pre- occupied by managing others’ guilt it might lead to discomfort with closeness and that the person is tuned in for achievement rather than relationships. Consciousness about others’ anger contributed significantly to all three patterns of attachment and explained a larger part of the variance than any other single affect. To be able to experi- ence and respond to others’ anger consequently seems to be particularly important for developing a secure attachment style and defending oneself against insecure attachment. This obser- vation is in line with findings in Feeney (1995), who found that emotional control was less prominent in the relationship be- tween two securely attached spouses than in relationships where both partners were insecurely attached. In a follow up study, a regression analysis of partner’s control of anger, sad- ness and anxiety showed that the negative emotions accounted for parts of the variance in relationship satisfaction “to a greater degree than what was explained by attachment dimensions” (Feeney et al., 1998). Satisfaction was, in fact, directly linked to the partner’s control of anger. Feeney et al. (1998) concluded that the result should not be interpreted to imply that it is posi- tive to suppress anger, but rather that it is the way in which anger is expressed and experienced that matters. In fact, ade- quate communication of anger may even strengthen the rela- tionship between the angry person and the person who is the target of the anger (Izard, 1991). This is, of course, dependent of the way anger is expressed but also dependent on the han- dling of anger by the targeted person. In a study by Mikulincer (1998), insecure persons were more prone to attribute hostile intent to the partner than were secure persons. If a person who is the target of anger has a problem in handling others’ affects, and especially others’ anger, this seems to interfere with their way of being in close relations. If a person is able to reflect on the experience of another person’s affects and especially the other person’s anger, they seem to be more able to feel secure in close relations. This might of course also influence how the individual attributes the others’ intent. There are limitations that should be considered when inter- preting our results. Firstly, the cross-sectional nature of this study restricts the possibility of drawing any conclusions regarding causality. Secondly, a choice was made to regress the affects on the at- tachment subscales. This choice could be questioned as the data were cross-sectional. Lastly, the participants were both patients and non-clinical individuals. This can be seen both as a prob- lem and as an asset. While a broad sample increases the likeli- hood of getting variation in affect consciousness and attach- ment style, the individual subgroups were too small to allow subgroup analyses in the correlation analyses. In conclusion there were associations between high affect consciousness and secure attachment, and between low affect consciousness and insecure attachment. The contribution of consciousness about others’ affects was somewhat higher than the contribution of consciousness about own affects. Con- sciousness about others’ anger in particular had special impor- tance for the variation in self-assessed attachment style. Con- sciousness about others’ guilt contributed significantly to the variance in avoidant attachment style, and own joy accounted significantly for variance in the ratings of anxious attachment. To be able to experience and respond to others’ affects and especially anger consequently seems to contribute to the de- velopment of a secure attachment style. A person’s problems with handling affects and especially others’ anger may inter- vene in his or her way of managing close relations. These findings may have implications for psychological treatment where affects and the regulation of affects in the therapy relationship can be vital. A number of different psy- chological methods aim especially at changing maladaptive affective patterns. Examples are Mentalization-based therapy (Bateman & Fonagy, 2003), Process-experiential therapy (Elli- ott, Watson, Goldman, & Greenberg, 2004), Accelerated Expe- riential Dynamic Psychotherapy (Fosha, 2000), Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (Hayes, Strosahl, & Wilson, 1999), Dia- lectical Behavior Therapy (Linehan, 1987a, 1987b, 1993) and Brief Relational Therapy (Safran & Muran, 2000). Knowledge about the relationship between specific affects or specific di- mensions of affects and the capacity for interpersonal and inti- mate relationships might be helpful to psychotherapists and counselors using these therapies. However, further research has to be carried out before any more conclusive statements can be made about the relation between adult attachment relationships and consciousness about own and others’ affects and its implications for treatment and treatment relationships. REFERENCES Ainsworth, M. D. S., Blehar, M. C, Waters, E., & Wall, S. (1978). Pattern of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation. New York: Erlbaum. Bateman, A., & Fonagy, P. (2003). The development of an attachment- based treatment program for borderline personality disorder. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic, 67, 187-211. doi:10.1521/bumc.67.3.187.23439 Barry, R. A., Lakey, B., & Orehek, E. (2007). Links among attachment dimensions, affect, the self, and perceived support for broadly gener- alized attachment styles and specific bonds. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 33, 340-353. doi:10.1177/0146167206296102 Belsky, J., & Cassidy, J. (1994). Attachment: Theory and evidence. In M. Rutte, & D. Hay (Eds.), Development through life: A Handbook for Clinicians (pp. 373-402). Oxford: Blackwell. Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss, Vol. 1. Attachment. London: Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psycho-Analysis. Choi-Kain, L. W., & Gunderson, J. G. (2008). Mentalization: Ontogeny, assessment, and application in the treatment of borderline personality disorder. American Journal of Ps ych iatr y, 165, 1127-1135. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07081360 Eagle, M. (1997). Attachment and psychoanalysis. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 70, 217-229. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8341.1997.tb01901.x Elliott, R., Watson, J. C., Goldman, R. N., & Greenberg, L. S. (2004). Learning emotion-focused therapy: The process-experiential ap- proach to change. Washington DC: American Psychological Asso- ciation. doi:10.1037/10725-000 Feeney, J. (1995). Adult attachment and emotional control. Personal Relationships, 2, 143-159. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6811.1995.tb00082.x Feeney, J., Noller, P., & Hanrahan, M. (1994). Assessing adult attach- ment. In M. B. Sperling, & W. H. Berman (Eds.), Attachment in adults (pp. 128-151). New York: The Guilford Press. Feeney, J., Noller, P., & Roberts, N. (1998). Emotion, attachment, and satisfaction in close relationships. In P. A. Andersen, & L. K. Guer- rero (Eds.), Handbook of communication and emotion, research, the- Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 679  B. LECH ET AL. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 680 ory, applications, and contexts (pp. 473-505). London: Academic Press. Fonagy, P. (2001). Attachment theory and psychoanalysis. New York: Other Press. Fonagy, P., Gergely, G., Jurist, L.E., & Target, M. (2004). Affect regu- lation, mentalization, and the development of the self. London: Kar- nac. Fonagy, P., Steele, H., Moran, G., Steele, M., & Higgitt, A. (1991). The capacity for understanding mental states: The reflective self in parent and child and its significance for security of attachment. Infant Men- tal Health Journal, 13, 200-217. Fonagy, P., & Target, M. (1998). Mentalization and changing aims of child psychoanalysis. Psychoanalytic Dialogues, 8 , 87-114. doi:10.1080/10481889809539235 Fosha, D. (2000). The transforming power of affect: A model for accel- erated change. New York: Basic Books. Fraley, R. C. (2002). Attachment stability from infancy to adulthood: Meta-analysis and dynamic modelling of developmental mechanisms. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 6, 123-151. doi:10.1207/S15327957PSPR0602_03 George, C., Kaplan, N., & Main, M. (1985). Adult Attachment Inter- view. Unpublished manuscript, Berkeley, CA: University of Califor- nia. Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K., & Wilson, K. G. (1999). Acceptance and commitment therapy. New York: Guilford. Hazan, C., & Shaver, P. R. (1987). Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 511-524. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.52.3.511 Håkanson, A., & Tengström, A. (1996). Attachment Style Question- naire—Översättning Till Svenska Samt Inledande Utprovning [At- tachment Style Questionnaire—Translation to Swedish and Prelimi- nary Evaluation]. Umeå: Umeå Universitet. Izard, C. (1991). The psychology of emotions. New York: Plenum Press. Lech, B., Andersson, G., & Holmqvist, R. (2008). Consciousness about own and others’ affects: A study of the validity of a revised version of the affect consciousness interview. Scandinavian Journal of Psy- chology, 49, 515-521. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9450.2008.00666.x Linehan, M. (1987a). Dialectical behavioral therapy: A cognitive be- havioral approach to parasuicide. Journal of Personality Disorders, 1, 328-333. doi:10.1521/pedi.1987.1.4.328 Linehan, M. (1987b). Dialectical behavior Therapy for borderline per- sonality disorder: Theory and method. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic, 51, 261-276. Linehan, M. (1993). Cognitive behavioral treatment of borderline per- sonality disorder. New York: Guilford Press. Mikulincer, M. (1998). Adult attachment style and individual differ- ences in functional versus dysfunctional experiences of anger. Jour- nal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 513-524. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.74.2.513 Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2005). Attachment theory and emo- tions in close relationships: Exploring the attachment-related dy- namics of emotional reactions to relational events. Personal Rela- tionships, 12, 142-168. doi:10.1111/j.1350-4126.2005.00108.x Mohaupt, H., Holgersen, H., Binder, P.-E., & Nielsen, G. H. (2006). Affect consciousness or mentalization? A comparison of two con- cepts with regard to affect development and affect regulation. Scan- dinavian Journal of Psychology, 47, 237-244. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9450.2006.00513.x Monsen, J., Eilertsen, D. T., Melgård, T., & Ödegård, P. (1996). Af- fects and affect consciousness: Initial experiences with the assess- ment of affect integration. Journal of Psychotherapy Practice and Research, 5, 238-249. Roisman, G. I., Holland, A., Fortuna, K., Fraley, R. C., Clausell, E., & Clarke, A. (2007). The adult attachment interview and self-reports of attachment style: An empirical rapprochement. Journal of Personal- ity and Social Psychology, 92, 678-697. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.92.4.678 Riggs, S. A., Paulson, A., Tunnell, E., Sahl, G., Atkison, H., & Ross, C. A. (2007). Attachment, personality, and psychopathology among adult inpatients: Self-reported romantic attachment style versus Adult Attachment Interview states of mind. Development and Psychopa- thology, 19, 263-291. doi:10.1017/S0954579407070149 Safran, J., & Muran, C. (2000). Negotiating the therapeutic alliance: A relational treatment guide. New York: Guilford Press. Searle, B., & Meara, N. M. (1999). Affective dimensions of attachment styles: Exploring self-reported attachment style, gender, and emo- tional experience among college students. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 46, 147-158. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.46.2.147 Woodhouse, S. S., & Gelso, C. J. (2008). Volunteer client adult attach- ment, memory for in-session emotion, and mood awareness: An af- fect regulation perspective. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 55, 197-208. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.55.2.197

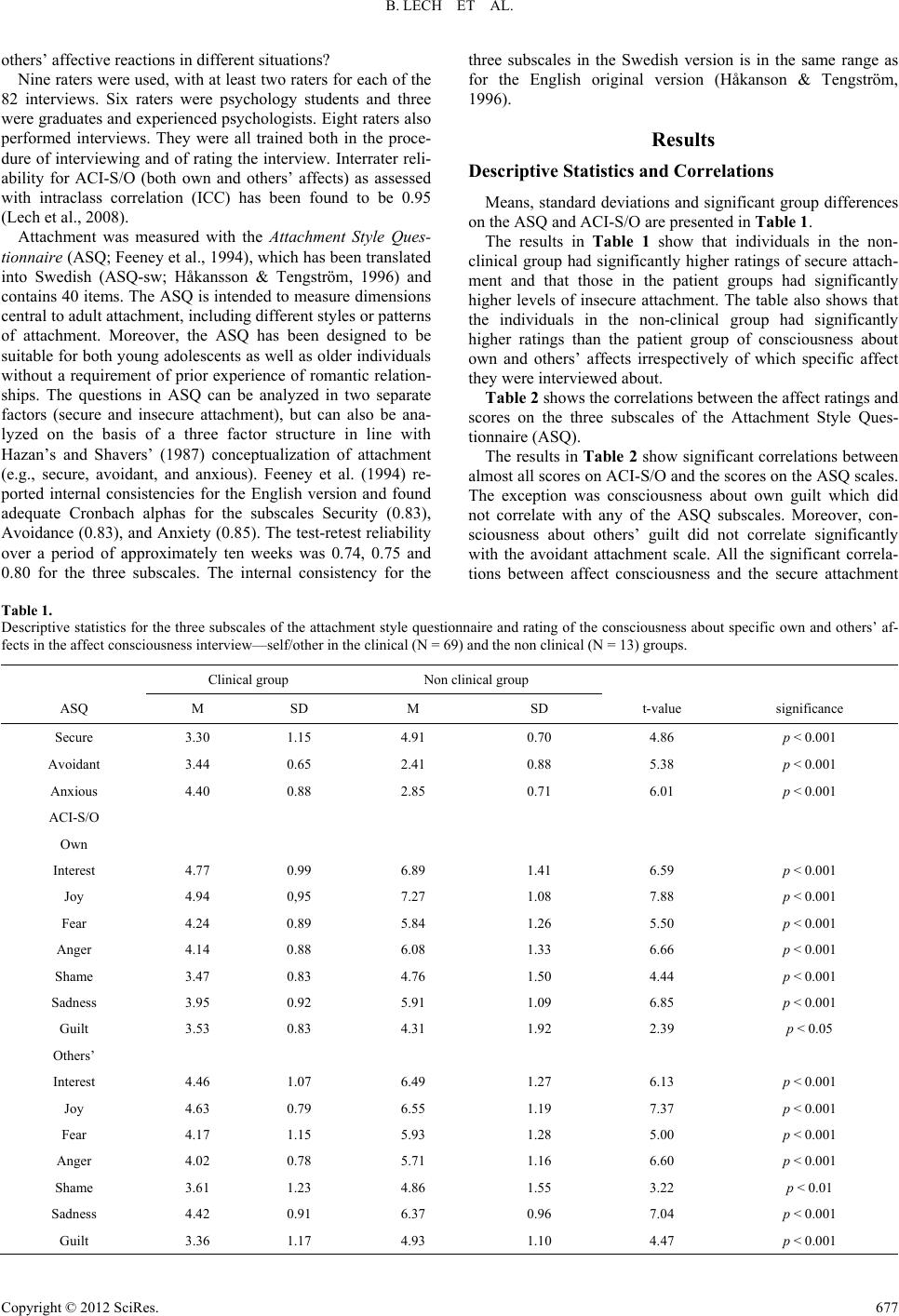

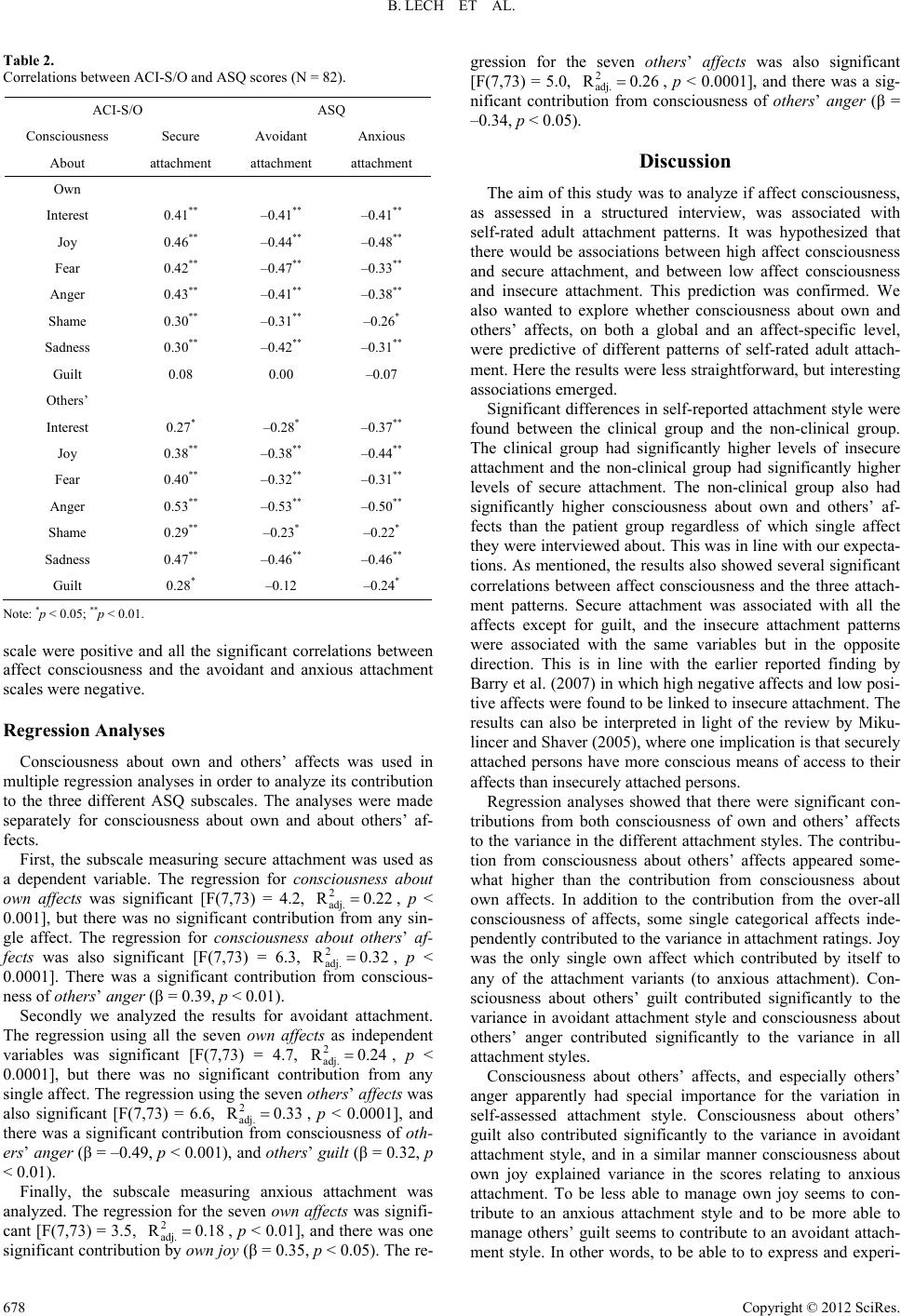

|