Open Journal of Modern Linguistics 2012. Vol.2, No.2, 51-56 Published Online June 2012 in SciRes (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/ojml) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojml.2012.22007 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 51 Waiting for Redemption in The House of Asterion: A Stylistic Analysis Martin Tilney Macquarie University, Sydney, Australia Email: martinjtilney@hotmail.com Received February 20th, 2012; revised March 7th, 2012; accepted March 15th, 2012 The House of Asterion is a short story by Jorge Luis Borges that retells the classical myth of the Cretan Minotaur from an alternate perspective. The House of Asterion features the Minotaur, aka Asterion, who waits for “redemption” in his labyrinth. Many literary critics have suggested that the Borgesian labyrinth is a metaphor for human existence and the universe itself. Others have correctly interpreted Asterion’s ironic death at the hands of Theseus as his eagerly awaited redemption. Borges’ subversion of the reader’s expectations becomes the departure point for a systemic functional stylistic analysis of the story in one of its English translations, revealing how deeper-level meanings in the text are construed through its lexico- grammatical structure. A systemic functional stylistic reading suggests that on a higher level of reality, Asterion’s redemption is not only the freedom that death affords, but also a transformation that transcends his fictional universe. Asterion’s twofold redemption is brought about not only by the archetypal hero Theseus but also by the reader, who through the process of reading enables Asterion’s emancipation from the labyrinth. Keywords: The House of Asterion; Borges; Minotaur; Labyrinth; Systemic Functional; Stylistic Introduction Argentinean writer Jorge Luis Borges (1899-1986) is best known as an early postmodernist (Frisch, 2004; Nicol, 2009; Sickels, 2004). Some of his most famous works from the early 1940s including Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius (1940), The Gar- den of Forking Paths (1941) and Death and the Compass (1942) have been widely studied as key postmodern texts, yet other stories such as The House of Asterion (1947) have received relatively little critical attention. The House of Asterion was originally published in Spanish in the literary journal Sur in 1947 and was reprinted in Borges’ second collection of stories The Aleph (1949). The present analysis involves an extract from The House of Asterion as translated by Andrew Hurley (Borges, 1949) and explores the lexicogrammatical and stylistic charac- teristics of Hurley’s interpretation. The analysis, therefore, may not accurately represent the lexical, semantic and stylistic fea- tures of the original Spanish text. The analysis also overlooks inconsistencies with other interpretations by the likes of Nor- man Thomas di Giovanni and James E. Irby. The Aleph was published in a period of Borges’ life that some biographers refer to as his “dark days” (Sickels, 2004) due to despair in his personal life and the onset of hereditary blindness. By 1955 Borges was completely blind (Zamora, 1995) but he continued writing long after he had lost his sight. Borges wrote his best-known fiction at a time when Argentina, following the Great Depression, had become one of the world’s wealthiest countries (Sullivan, 2002). In the 1930s, Argentina’s fast-paced industrialisation replaced traditional ways of life with a new set of values, demands, and social factors (Rincon, 1993). In other words, it was during this time that the nation went through a period of modernity, which in turn provided the ideal condi- tions for the development of modernism and postmodernism in the latter half of the twentieth century (for a detailed discussion of the difference between the terms “postmodernity” and “postmodernism” see Hassan, 2001). These social and eco- nomic conditions, as well as Borges’ international success, undoubtedly contributed to the Latin American “boom” of postmodern and magic realist fiction in the 1960s. The term “postmodernism” is a notoriously problematic label, and to attempt a crude summary of all the various and contentious characteristics of postmodern fiction is well outside of the scope of this paper. However, the story does involve at least one important feature of postmodern fiction, which is the “ten- dency to draw the reader’s attention to his or her own process of interpretation as s/he reads the text” (Nicol, 2009: p. xvi). This capacity to raise the reader’s interpretative awareness is implied by literary critics such as Bell-Villada (1999), Davis (2004) and Peyronie (1992b), who all describe the story as a journey from uncertainty to assurance that Asterion, the pro- tagonist and narrator, is indeed the Minotaur of the legend. The story enables this process of affirmation by recounting the clas- sical Cretan myth of the Minotaur from the Minotaur’s perspec- tive. The narrator’s identity is foreshadowed in the title and epigraph, but for most readers, the moment of recognition comes at the end of the story (Bell-Villada, 1999; Davis, 2004; Peyronie, 1992b) when Theseus remarks, “the Minotaur scarcely defended itself” (Borges, 1949: p. 222). In this paper I wish to go a step further and demonstrate through a stylistic analysis of the text that the protagonist is not only confirmed (and, para- doxically, challenged) as a familiar archetype, but also elevated to a higher realm that can only be perceived by the reader. Labyrinths and Mythology As the title suggests, The House of Asterion is set in the Cre-  M. TILNEY tan labyrinth, which is described by a plethora of different au- thors throughout history. The Theoi Greek Mythology website (Atsma, 2011) alone lists sixteen sources of the legend under the entry “Minotauros” ranging from the second to the tenth century AD. In literature, the labyrinth, as Peyronie (1992a) points out, has a rich symbolic significance from as early as the Middle Ages when the myth of the labyrinth was adopted by Christianity and became a symbol of hell and the Devil (from which, fortunately, there was redemption by Theseus/Christ). In the fourteenth century the labyrinth was still a threatening im- age but pre-Renaissance poets came to believe that just as peo- ple exist within the labyrinth, the labyrinth also exists inside people. In the eighteenth century the labyrinth became a phi- losophical symbol of the finite and the infinite, with the centre of the labyrinth representing the unattainable meaning of the universe. This concept became more complicated towards the twentieth century, which is referred to as the “age of the laby- rinth” because of the predominance of labyrinths in the litera- ture of the time. Borges’ work features labyrinths as a common motif and is often concerned with the various literary meanings that labyrinths have acquired over the centuries. Some critics have interpreted the centre of the Borgesian labyrinth as the centre of human existence (Murillo, 1959; Dauster, 1962) or the centre of the universe (Frisch, 2004), and virtually all of Bor- ges’ characters strive to experience a moment of enlightenment at this centre. In many cases, this enlightenment is a justifica- tion of life that inevitably ends in death (Dauster, 1962). Some critics interpret this search for meaning in a chaotic world as a lost cause, claiming that many of Borges’ characters who struggle with futile existential questions are only able to find peace in the awareness of self-limitation (Lyon & Hangrow, 1974: p. 25). Other critics suggest that such characters resign themselves to death in favour of confronting the terrible nature of reality. Without specific reference to The House of Asterion, Dauster points out that: [t]he narrations contained in El Aleph repeat a predominant theme: man’s hallucinated search for the center of the labyrinth of his existence. We have also seen a suggestion that at the center lies something closely akin to the mystics’ communion with the infinite, an experience which reveals the fundamental truths of existence, and which awakens a feeling of resignation and a willingness to accept death, possibly because the alterna- tive, once perceived, is too horrible to accept. (Dauster, 1962: p. 144) In addition to existential meanings, the labyrinth also has a religious significance. In some ancient civilisations such as Egypt and Babylon, the labyrinth was sometimes a location for “actions of divinity” including rebirth (Murillo, 1959). In the story, Asterion considers his labyrinth as a religious place. He narrates, “every nine years, nine men come into the house so that I can free them of all evil” (Borges, 1949: p. 221). This divine act of redemption, which echoes the Lord’s prayer from the Christian faith, may just be a euphemism for “killing” (Bell-Villada, 1999) and indeed, Asterion may not be aware that his so-called “god-like powers” do not actually exist (Frisch, 2004). In any case, Asterion finds meaning in the events of his somewhat meaningless existence. This alternate perspective subverts the “classic” versions of the tale, which despite their many inconsistencies with specific details, share the common feature of denying the Minotaur’s purpose. In fact, throughout history the Minotaur has been portrayed as either the manifesta- tion of horror, the complexities of monstrosity or the foil of Theseus, and only since the late 1800s has the beast provided “systematic food for thought rather than simply firing the imagination” (Peyronie, 1992b: p. 820). The Minotaur is por- trayed in this way in George Frederick Watts’ painting The Minotaur (1885), in which the lonely creature is looking out to sea with a little bird crushed under his hand. He seems to be waiting for someone to arrive, and a look of dejection in his posture suggests that he is as pitiful as he is beastly (Bell-Vil- lada, 1999; Davis, 2004). The painting inspired Borges, who conveys the same ambiguity in his story. In this way, Asterion both challenges and enriches the classic myth. For the sake of convenience I will reproduce a summary of the Cretan myth from the Companion to Literary Myths, Heroes and Arche- types: Minos asked Poseidon to give a sign to prove to the Cretans that he was favoured by the gods. The god agreed, on condition that the bull that he would cause to rise from the sea, would subsequently be offered to him as a sacrifice. However, the animal was so beautiful that Minos could not bring himself to destroy it in this way. Poseidon was furious and decided to take his revenge by making Queen Pasiphae fall passionately in love with the white bull. Longing to be united with the animal, the queen enlisted the help of the ingenious Athenian, Daedalus, who was at the court of Minos. The artisan used his skill to create a heifer out of wood and leather. The queen concealed herself inside the heifer and the white bull, deceived by ap- pearances, coupled with her. The fruit of this unnatural union was the Minotaur, also known as Asterion or Asterius, which had the head of a bull and the body of a man. Furious and ashamed, Minos had Daedalus construct a sort of huge pal- ace-prison, the labyrinth, in which to keep the monster. Every year (or every nine years), seven youths and seven maidens were fed to the Minotaur, a tribute imposed on the Athenians by Minos. One day, Theseus suggested that he join the group of youths and, with the help of the thread given to him by Ariadne, he found the Minotaur, killed it and emerged, triumphant, from the labyrinth. (Peyronie, 1992b: p. 814) The legend, as described above, exists in many different variations, but each version generally tells the same story with a focus on the sequence of events rather than character develop- ment. Borges’ story, on the other hand, retells the myth from the Minotaur’s own point of view. Locked away for no appar- ent reason, Asterion lives all alone in his house and spends most of his time playing games and pretending. Though he has an imaginary friend—a projection of himself, it is only with outsiders, unfortunate youths chosen to be sacrificed, that Aste- rion experiences real interaction. It is ambiguous from Aste- rion’s narrative whether he actually kills the victims or not, but evidence suggests that he does so with the belief that killing them is an acceptable, even morally positive deed. Some critics assume that Asterion is unaware of committing murder, but as will be discussed later, it seems that he genuinely believes he is capable of freeing people from evil. One day, during a human sacrifice ritual, a dying man prophesises that Asterion’s re- deemer will come, and although the need for redemption is never explicated, Asterion is obsessed with the idea of his sav- iour. In the end, Asterion finds his redemption, ironically, in death. He is killed by the “hero” Theseus and is thus “re- deemed” from his incarceration. These events are all narrated by Asterion in the first person. The recount takes the form of an interior monologue containing no quotation marks that would imply actual communication with other characters. Rather, the Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 52  M. TILNEY reader accesses his thoughts directly, which effectively helps to give a voice to a “marginal character” (Davis, 2004: p. 141) and provides the Minotaur with a “developed consciousness and a human share of existential anxieties” (Bell-Villada, 1999: p. 150). In this way, Borges turns the legend upside-down, rede- fining the Minotaur who is then reabsorbed into the mythical canon, thus confirming the labyrinth as a place of transforma- tion and rebirth. Although critics have already discussed the transformation of the Minotaur in The House of Asterion, none have read the story from a systemic functional perspective. A systemic functional stylistic approach reveals empirical evi- dence to support or challenge existing literary interpretations as well as enabling new readings. The systemic functional model of grammar (Halliday & Matthiessen, 2004) is particularly relevant to the present analysis because it sheds light on the Process types involved in the representation of outer and inner worlds, which play a significant part in construing deeper-level meaningsin the story (for discussions on how systemic func- tional stylistics reveals deeper-level meanings, see Butt, 1983; Halliday & Webster, 2002; Hasan, 1985). Consciousness In the traditional version of the myth, the shameful Minotaur is hidden from the public eye; however, it is never suggested that the Minotaur himself is aware of his punishment, let alone conscious of anything. The present analysis focuses on a selec- tion of 31 clauses (see Appendix 1) that reveal interesting in- sights into Asterion’s consciousness, particularly his thoughts and feelings that convey the depth and complexity of his char- acter. In systemic functional linguistics, the Mood system of a text is the series of informational exchanges between speaker/ listener or reader/writer. The Mood consists of the Subject (a nominal group) and the Finite (part of a verbal group) (Halliday & Matthiessen, 2004: p. 111). The selection of Mood gives a text or dialogue its “characteristic flavour” and in this case, gives Asterion his voice. In the extract almost all clauses (26/31) are declarative statements, conveying information from the narrator to the reader. The statements describe Asterion’s real- ity, which is defined by the unaccountable human sacrifice ritual, followed by a distinct shift in Mood whereby interroga- tive questions conclude the text: (27) What will my redeemer be like? (28) I wonder. (29) Will he be bull or man? (30) Could he possibly be a bull with the face of a man? (31) Or will he be like me? This shift in Mood starting at clause 27 foregrounds Aste- rion’s obsession with his prophesised redeemer. The interroga- tive questions could have been written as declarative statements with a different effect: (i) What will my redeemer be like, I wonder? (ii) I wonder what my redeemer will be like. In the text, the interrogative question form is used, as in (i) above, rather than a declarative statement, which would look like (ii). The effect is a more direct connection to Asterion’s thoughts, without the mediation of a narrator. Through this foregrounding of Mood, Hurley emphasises Asterion’s obses- sion with his redeemer. Without the authority of an omniscient narrator, there is no proof that the redeemer really exists, but for Asterion there is no doubt. The Wait Asterion’s obsessive faith in his redeemer is reinforced by the Thematic structure of the text. According to systemic func- tional linguistics, Theme is the departure point of the clause, which gives the clause its “character as a message” (Halliday & Matthiessen, 2004: p. 64). Examining the Theme structure of a text provides an insight into the way the text unfolds. In the following analysis, I will only examine Experiential Themes (for a description of other Theme types see Thompson, 2004) since Experiential Themes are predominant in this text. The most frequently occurring Theme is “I” (10/28), which is to be expected in monologic first person narrations. The next most frequently occurring Theme is the human sacrifice “ceremony” (from this point on “ceremony” and “ritual” will be used inter- changeably), which accounts for 7/28 of all Experiential Themes. The foregrounding of the ritual as Theme in the text construes the significance of the event from the narrator’s per- spective. Indeed, in an impossibly lonely world almost absent of human contact it is no surprise that Asterion actively searches for meaning in this macabre interaction with people. It is also not surprising that Asterion unquestioningly believes an outsider who prophesises the arrival of a “redeemer”. These are arguably the only words ever spoken to Asterion by a real per- son. Asterion’s obsession with his redeemer is reflected in the selection of Theme, with the redeemer accounting for 6/28 of the Themes. Of the remaining Themes, 4/28 are time references, all of which are foregrounded Themes. The Theme is said to be marked when it is not the gram- matical Subject in declarative clauses. The choice of a marked Theme presumes a reason for the Theme to be foregrounded in such a way. (iii) Every nine years, nine men come into the house (iv) Nine men come into the house every nine years The text uses the marked Theme in (iii) above rather than the potentially unmarked version (iv). In (iii), the grammatical Subject of the clause is “nine men” but the departure point of the clause is “every nine years”. Compared to the potential unmarked Theme (iv), the period of time is more important than the people. Altogether, there are six marked Themes in the text: three of which refer to counting (clauses 1, 7, 13) and three of which refer to a point in time (clauses 17, 18, 21). The markedness of counting-related Themes reveals that although Asterion counts the years between the arrival of the outsiders (every nine years) he has lost count of, or is not concerned with the number of victims who have died (one after another, how many). Thus, the wait for redemption is foregrounded. Of the marked “time” Themes, two describe the coming of the re- deemer (some day, in the end) and the other conveys the idea that faith removes the pain of loneliness (since then). (vi) Since then, there has been no pain for me in solitude (vii) There has been no pain for me in solitude since then Of the two examples above, Hurley chooses the marked Theme (vi), effectively foregrounding the day of the prediction. The syntactic choice suggests that for Asterion, neither the loss of human life nor loneliness is as important as the arrival of his hero. He waits for “redemption” (whatever that means), count- ing the years and perhaps finding disappointment when the audible footsteps turn out to be regular people. According to the myth, Theseus arrives at the labyrinth with a group of sacrifi- cial offerings and slays the Minotaur. During the Renaissance, this victory was praised as a heroic triumph of good over evil Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 53  M. TILNEY (Peyronie, 1992b) but in Borges’ story the victory seems shal- low because Asterion welcomes his ironic destiny without re- sistance. Is it possible that Asterion actually wants to die? In the story, he mentions how he enjoys pretending to be hunted and hurling himself from rooftops (Borges, 1949: p. 221). Perhaps Asterion knows the terrible reality of his existence and engages in self-destructive behaviour as he awaits the final redemption of death. Redemption & Blind Faith Asterion’s preoccupation with the idea of redemption has al- ready been demonstrated, but what exactly does redemption mean for him? What has Asterion done to deserve his impris- onment? In the story, he mentions that his royal lineage pre- vents him from “mixing with commoners” (Borges, 1949: p. 220). Is this another of Asterion’s delusions, or could he be aware of his hideous nature, simply choosing not to confront it? An analysis of the text’s Transitivity system supports the notion that Asterion is blind to reality (Davis, 2004), but fails to dis- ambiguate delusion from ironic comprehension. The following discussion presumes a distinction between the real and the imaginary, but before commenting on Asterion’s ability to un- derstand his self and his world, I would mention that he might not be as ignorant as some critics would suggest. On the con- trary, Asterion’s delusions might be an intentional effort to make his unfathomable reality meaningful: In his stories Borges does not set everyday reality against a more convincing “reality” of thought; in fact, he scrupulously blurs the differences between these two levels. But in the pat- tern of all of them is the implicit opposition between bewitch- ment or blind faith and ironic comprehension. In an essay he quotes Novalis’s description of man’s self-deception: the greatest wizard is the one who enchants himself to the point of taking his own fantasmagoria for autonomous appearances. Borges argues that such is our case. We have dreamed the world but we have left certain tenuous interstices of unreason in order to know that it is false. (Weber, 1968: p. 140, my em- phasis) According to systemic functional linguistics, the Transitivity system represents the world through a “manageable set of Process types” (Halliday & Matthiessen, 2004: p. 170). These Process (verb) types include Material Processes, which construe the outer world and Mental Processes, which construe the inner world of experience. The text under examination consists mostly of Material (12/29) and Mental (9/29) Processes. A closer inspection of Material and Mental Process types in the text reveals a worldview that is almost exclusively absent of consequence. Material Processes can be either Transitive (the “doing” type) or Intransitive (the “happening” type). Whereas Transitive Processes have a grammatical “goal of impact”, Intransitive Processes do not: (vii) so that I (Agent) can free (Pro:ma) them (Goal) of all evil (Circ) (viii) so that I (Agent) can absolve (Pro:ma) In the examples above, the Intransitive version (viii), con- tains a Process that does not make an impact on an entity, and is thus less impinging than its Transitive counterpart. In the text, the predominant type of Material Process is Intransitive. The implication is that in Asterion’s world actions have little con- sequence. Of the 14 clauses only three of them (clauses 2, 11, 26) are Transitive. In other words, only three clauses have a Goal of impact. Since these Transitive clauses are foregrounded, it is worth taking a closer look at them. (2) so that I (Agent) can free (Pro:ma) them (Goal) from all evil (Circ) (11) and their bodies (Agent) help distinguish (Pro:ma) one gallery (Goal) from the others (Circ) (26) he (Agent) takes (Pro:ma) me (Goal) to a place with fewer galleries and fewer doors (Circ) Whereas clause 26 comes from Asterion’s imagination, cla- uses 2 and 11 are “real” in the sense that they are unimagined interactions in Asterion’s physical world. In clause 2, Asterion claims to “free” the outsiders, whose dead bodies form land- marks that help to make the labyrinth less confusing. These two “real” Transitive Processes are both concerned with the ritual. The suggestion is that “participating” in the ritual is the only way for Asterion to make an impact on, and therefore exist meaningfully in his outer world. In an Intransitive space where action lacks impact, it is no surprise that Asterion infers mean- ing from his limited contact with the outside world. From the reader’s perspective, the sacrificial ceremony is just a part of the story. But trapped within the labyrinth of the fictional narra- tive, Asterion is unable to perceive this higher-level reality, and is unwilling to accept the apparent meaninglessness of the event. Asterion, alone in an Intransitive world, tries to imagine his redeemer and waits eagerly for him. Although he does not de- fine what his redemption actually means, the Transitivity sys- tem offers a clue. Asterion hopes that his redeemer will “take him to a place with fewer galleries and fewer doors” (clause 26). As a Transitive Process, his desire to be free of the labyrinth is construed as a powerful thought—a Process that expresses a real impact on the grammatical Goal, Asterion: (25) I hope (26) he takes me (Goal) to a place with fewer galleries and fewer doors Asterion does not tell us exactly where the redeemer will take him, but he implies that it is outside the labyrinth. Also, since this is one of the few Transitive Processes being fore- grounded, it seems that Asterion is preoccupied with the idea of escape. If we read the labyrinth as a metaphor for Asterion’s existence, redemption means death. But what is the implication if we take the labyrinth to be a metaphor for his fictional uni- verse? Before attempting to answer this question I will first comment on Asterion’s ostensible shortsightedness. Despite his claims earlier in the story to have walked the streets outside of the labyrinth and despite his claim not to be a prisoner (Borges, 1949: p. 220) Asterion’s apparent blindness would prevent him from finding his way out of the labyrinth by himself. Just as Material Processes construe the outer world of experience, Mental processes construe the inner world. Of the nine Mental Process clauses, only three (clauses 3, 23, 24) have a non-Projected Phenomenon. A Phenomenon is defined as that which is “felt, thought, wanted or perceived” (Halliday & Mat- thiessen, 2004: p. 203). A Phenomenon can either be like a “fact” or an “act”: (viv) I (Senser) hear (Pro:me) their footsteps (Phen) or their voices (Phen) (x) I (Senser) hear (Pro:me) [[how they walk or speak]] (Phen) Similar to Goal in Material clauses, fact-like Phenomena, as in (viv) are more concrete than act-like Phenomena (x). The text contains three such fact-like Phenomena (clauses 3, 23, 24). In each case, the Mental Process is “hear” and the Phenomenon Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 54  M. TILNEY is a sound. The suggestion is that Asterion’s most reliable sense is his hearing. In the extract under analysis, there is a complete absence of “seeing” Processes. It should also be noted that elsewhere in the story there is no proof that Asterion actually sees anything, though his imaginary other does. A closer look at the three fact-like Phenomena again suggests that the cere- mony is the only real event in Asterion’s life. (3) I (Senser) hear (Pro:me) their footsteps (Phen) or their voices (Phen) far away in the galleries of stone (Circ) (23) If my ear (Senser) could hear (Pro:me) every sound in the world (Phen) (24) I (Senser) would hear (Pro:me) his footsteps (Phen) Of the three clauses above, clause 3 is the only “real” event because clauses 23 and 24 are hypothetical. This means that in the whole text, Asterion only perceives one fact that is grounded in reality—the sound of human footsteps. In addition, Asterion seems to rely on his sense of hearing. Indeed, Asterion might literally beshortsighted. Except for a reference to a “night vision”, which could refer to a dream, a reference to the “col- ourless faces” of the people on the streets and a reference to the “colour of the day”, (Borges, 1949: p. 220), he makes no sug- gestion that he can actually see anything within the labyrinth. The motif of blindness in Borges’ work is often attributed to his failing eyesight (Zamora, 1995) and Padel (1996) interprets the Minotaur as an embodiment of the blind Eros. Asterion’s blindness can also be seen through a systemic functional read- ing, it reveals Asterion’s blind faith in redemption and suggests that Asterion is blind to insight. Hemis interprets the events that impinge on his world, but whether this misconception is in fact “ironic comprehension” remains ambiguous. Inner and Outer Labyrinths The House of Asterion provides the reader with a new per- spective of an ancient tale. The style of narration is monologic, allowing the reader to connect directly to Asterion’s psyche and experience the world through his consciousness. Through this experience, the reader realises that the labyrinth is a metaphor, chaotic and unexplainable, for Asterion’s very existence. Ac- cording to the myth, the Minotaur was condemned to a dark and nightmarish labyrinth because of his beastly nature. In The House of Asterion, the labyrinth is an intransitive space where actions have no impact and nothing makes sense. Within the labyrinth, the only “reality” is death—the death of the sacrifice victims and the death of Asterion himself. Everything else is either imagination or illusion. The Minotaur is incapable of understanding the mystery of his existence and thus creates his own meanings,which is common of Borges’ characters (Lyon & Hangrow, 1974). Asterion convinces himself that he is not a prisoner, but some kind of godly being who is able to absolve evil (this theme is also explored in other stories from The Aleph such as The Writing of the God). In his desperate attempt to find meaning he develops a blind faith in “redemption”. It is implied that for Asterion, redemption means escaping from the labyrinth. His destiny then unfolds on two separate levels of reality. In the narrative “inner” context, the Minotaur is freed from the labyrinth of his existence through death. Ironically, Asterion’s redeemer turns out to be Theseus, whose archetypal heroic role is subverted when he murders a defenceless and pitiable creature. The moment of revelation is marked by a sudden shift to omniscient third person narration: The morning sun shimmered on the bronze sword. Now there was not a trace of blood left on it. “Can you believe it, Ariadne?” said Theseus. The Minotaur scarcely defended itself. (Borges, 1949: p. 222) At the same time, redemption occurs in the story’s “outer” context, i.e. the world of the reader. Asterion’s incapability of perceiving the realm outside his fictional world is construed through the experiential Processes that he uses to describe his reality. Literary critics have claimed that Asterion is deluded and naïve, but it seems unfair to expect him to perceive a level of reality outside his fictional world. As McHale (2001) points out, “the fictional world is accessible to our real world, but the real world is not accessible to the world of fiction; in other words, we can conceive of the fictional characters and their world, but they cannot conceive of us and ours” (p. 35). Al- though Asterion may at first appear ignorant for consistently “missing the point,” his understanding of his world is uncannily accurate. Perhaps the message here is not the futility of ever understanding our selves and our universe, which presumes a single, absolute meaning, but a more hopeful message. If Aste- rion can find truth in his own self-deception, his own “fantas- mogoria”, then perhaps we can find it also. Borges once men- tioned in an interview that the labyrinth is a sign of hope rather than despair, because if indeed the universe is a labyrinth, it will have a centre of meaning, without which we are “truly lost” (Frisch, 2004: p. 27). While the labyrinth refers on the one hand to Asterion’s inner world in the narrative inner context, it also stands for his outer world, or his fictional universe, in the outer context of the “real” world. Through Borges’ text, Aste- rion is refigured in the reader’s mind as a conscious being that suffers the same despair, the same loneliness, and the same confusion as ordinary people. At the end of the story, in the moment when the unattainable is finally attained, the Minotaur dies and is reborn as Asterion, a son of royalty condemned to a life of suffering. In the mind of the reader, Asterion is freed from the labyrinth of his traditional fictional universe, from his archetypal role of monster in classical mythology. In this sense, the godlike saviour whose outward appearance Asterion can only imagine, is in fact the reader of the story. It is the reader who, through the process of reading, performs the magical rite of transforming a dreadful beast into a symbol of the human condition. Conclusion The House of Asterion is a story that frees the Minotaur from his nightmarish existence. His redemption is realised, not only in death, but also in the metamorphosis that occurs in the mind of the reader. Peyronie (1992b) points out that “it is impossible to kill the Minotaur. At the very most we can sacrifice it, in other words transform it…” (p. 821). In this paper, I have sug- gested that such a transformation is in fact the redemption that informs Asterion’s obsession, regardless of how fully he can comprehend it. Asterion’s reality depends on his redemption, which is achieved through his relocation from the margin to the centre of the fictional world. The shift is enabled through a metaphysical process that is achieved through the text’s ability to transcend its own boundaries. The stylistic analysis above does not acknowledge the extent to which the lexical and syn- tactic choices in Hurley’s English translation represent those of Borges’ original text La casa de Asterión. However, Borges’ literary mastery, discernible in Hurley’s exemplary work, makes The House of Asterion an exhilarating reading experi- Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 55  M. TILNEY Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 56 ence and an important example of postmodern fiction. REFERENCES Atsma, A. J. (2011). Theoi Greek mythology. http://www.theoi.com Bell-Villada, G. (1999). Borges and his fiction: A guide to his mind and art. Texas: University of Texas Press. Borges, J. L. (1949). The house of Asterion. In J. L. Borges, & A. Hur- ley (Eds.), Jorge Luis Borges collected fictions (pp. 220-222). New York: Penguin Books. Butt, D. (1983). Semantic drift in verbal art. Australian Review of Ap- lied Linguistics, 6, 38-48. Dauster, F. (1962). Notes on Borges’ labyrinths. Hipanic Review, 30, 142-148. doi:10.2307/472089 Davis, S. (2004). Rereading and rewriting traditions: The case of Bor- ges’ ‘La casa de Asterion’. Romance Studies, 22, 139-148. doi:10.1179/026399004786542942 Frisch, M. (2004). You might be able to get there from here: Reconsid- ering Borges and the postmodern. Cranbury, NJ: Rosemont Publish- ing & Printing Corp. Halliday, M. K., & Webster, J. (2002). Linguistic studies of text and discourse. London: Continuum. Halliday, M., & Matthiessen, C. (2004). An introduction to functional grammar (3rd ed.). London: Hodder Education. Hasan, R. (1985). Linguistics, language and verbal art. Geelong: De- akin University Press. Hassan, I. H. (2001). From postmodernity to postmodernism: The lo- cal/global context. Philosophy a nd Literature, 25, 1-13. doi:10.1353/phl.2001.0011 Lyon, T., & Hangrow, P. (1974). Heresy as motif in the short stories of Borges. Latin American Literary Review, 3, 23-35. McHale, B. (2001). Postmodernist fiction. New York: Routledge. Murillo, L. (1959). The labyrinths of Jorge Luis Borges: An introduc- tion to the stories of the Aleph. Modern Language Quarterly, 20, 259-266. doi:10.1215/00267929-20-3-259 Nicol, B. (2009). The Cambridge introduction to postmodern fiction. New York: Cambridge University Press. Padel, R. (1996). Labyrinth of desire: Cretan myth in us. Arion, 4, 76- 87. Peyronie, A. (1992a). The labyrinth. In P. Brunel (Ed.), Companion to literary myths, heroes and archetypes (pp. 685-719). London: Rout- ledge. Peyronie, A. (1992b). The minotaur. In P. Brunel (Ed.), Companion to literary myths, heroes, and archetypes (pp. 814-821). London: Routledge. Rincon, C. (1993). The peripheral centre or postmodernism: On Borges, Garcia Marquez, and alterity. Boundary 2, 20, 162-179. doi:10.2307/303348 Sickels, A. (2004). Biography of Jorge Luis Borges. In H. Bloom (Ed.), Jorge Luis Borges (pp. 5-22). Broomal: Chelsea House Publications. Sullivan, M. (2002). Argentina’s political upheaval. http://fpc.state.gov/documents/organization/7955.pdf Thompson, G. (2004). Introducing functional grammar (2nd ed.). London: Hodder Education. Weber, F. W. (1968). Borges’ stories: Fiction and philosophy. Hispanic Review, 36, 124-141. doi:10.2307/472042 Zamora, L. P. (1995). The visualizing capacity of magical realism: Ob- jects and expression in the work of Jorge Luis Borges. In L. P. Zamora, & W. B. Faris (Eds.), Magical realism: Theory, history, community (pp. 21-37). Durham: Duke University Press. Appendix 1. Clausal Units in an Extract from The House of Asterion CC1 C# Clausal Taxis Clause A 1 α Every nine years, nine men come into the house 2 xβ so that I can free them from all evil B 3 1 I hear their footsteps or their voices far away in the galleries of stone 4 +2 α and I run joyously 5 xβ to find them C 6 1 The ceremony lasts but a few minutes D 7 α One after another, they fall 8 xβ without my ever having to bloody my hands E 9 xβ Where they fall 10 α 1 they remain 11 +2 and their bodies help distinguish one gallery from the others F 12 α I do not know 13 ‘β 1 how many there have been 14 x2 α but I do know 15 ‘β α that one of them predicted 16 xβ α as he died 17 ‘β that someday my redeemer would come G 18 α Since then, there has been no pain for me in solitude 19 xβ α because I know 20 ‘β 1 that my redeemer lives 21 +2 1 and in the end he will rise 22 +2 and ^HE WILL stand above the dust H 23 xβ If my ear could hear every sound in the world 24 α I would hear his footsteps I 25 α I hope 26 ‘β he takes me to a place with fewer galleries and fewer doors J 27 ‘1 What will my redeemer be like 28 2 I wonder K 29 ‘1 Will he be bull or man L 30 ‘1 Could he possibly be a bull with the face of a man M 31 ‘1 Or will he be like me 1 CC stands for clause complex and C# represents the clause number. For a description of clausal taxis, clause units, and notation, see Halliday and Matthiessen (2004).

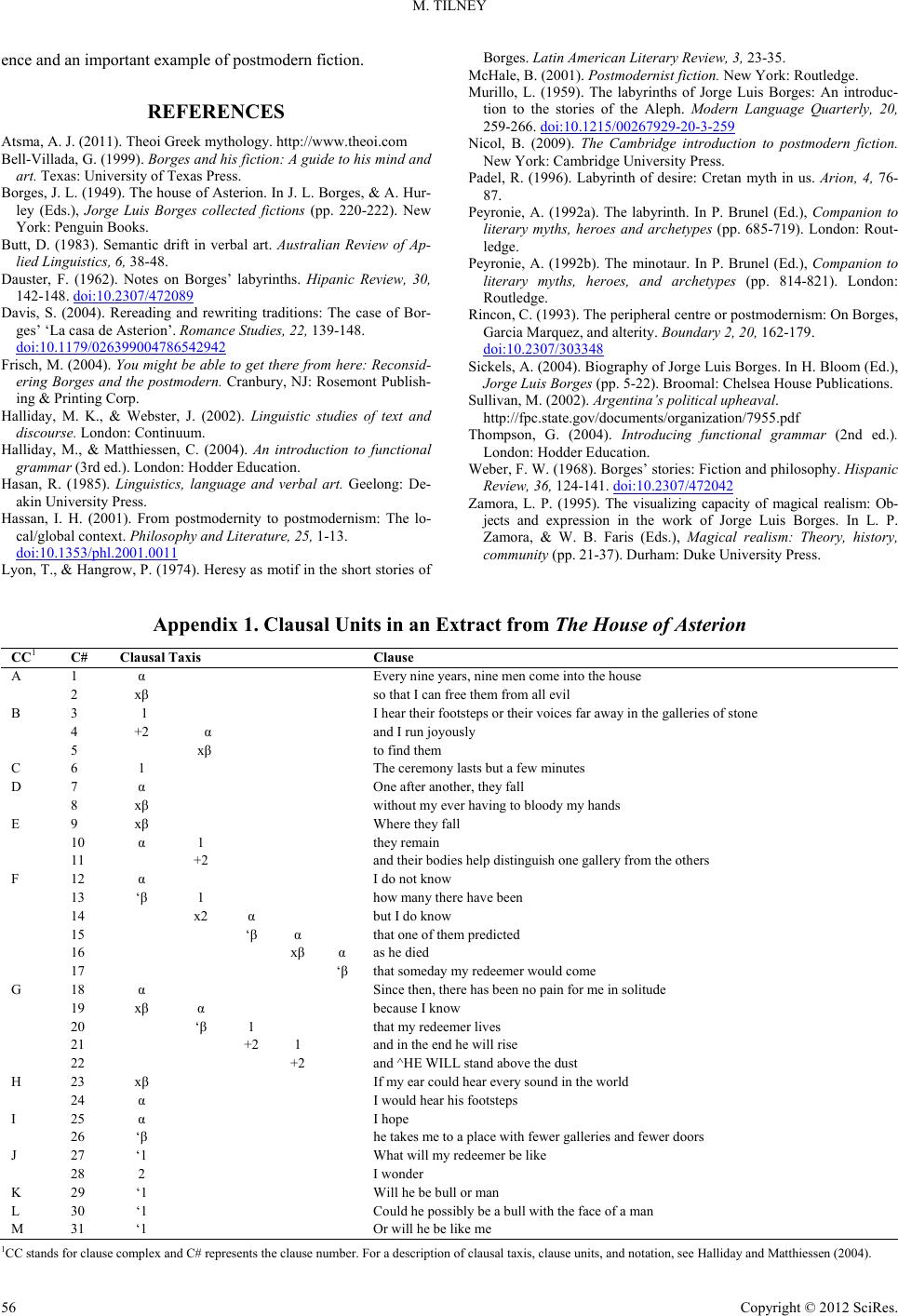

|