Open Journal of Nursing

Vol.2 No.3(2012), Article ID:23179,4 pages DOI:10.4236/ojn.2012.23042

Content of nursing discharge notes: Associations with patient and transfer characteristics

![]()

1Faculty of Health and Science, Nord-Trøndelag University College, Namsos, Norway

2Department of Health Sciences, Mid-Sweden University, Sundsvall, Sweden

3Department of Medicine, Division of Geriatrics, Nord-Trøndelag Health Trust, Namsos, Norway

4Centre for Care Research Mid-Norway, Steinkjer, Norway

Email: *rose.olsen@hint.no

Received 24 July 2012; revised 21 August 2012; accepted 1 September 2012

Keywords: Older People; Transfer; Nursing Documentation; Hospitalization; Home Care

ABSTRACT

Background: In situations of care transfer of older people from hospital to home care at discharge, exchanging relevant and necessary information about the patient’s health status and individual needs are of importance to ensure continuity and appropriate nursing follow-up care. Objective: The objectives of the study were to: 1) examine the content of nurses’ discharge notes of older patients’ discharged from hospital to home care; and 2) investigate the association between the content of discharge notes and characteristics of patient and transfer. Methods: The nursing discharge notes of 70 older patients admitted to a geriatric unit and a general medicine ward at a local hospital in central Norway were analysed. The discharge notes were structured in accordance with the Well-being, Integrity, Prevention, and Safety (VIPS) model. Mean, standard deviations, and independent sample t-tests were performed to show and examine differences in use of VIPS keywords in relation to patient and transfer characteristics. To examine if use of VIPS keywords could be predicted by patient and transfer characteristics, linear multiple regression analyses were used. Results: Significant differences for mean scores on used VIPS keywords in the discharge note were found for gender, age, and medical department facility. While gender and medical department facility were significant predictors of mental related keywords in the discharge note, medical department facility was a significant predictor of physical related keywords. Conclusions: The result of this study indicate that documentation of patient status in the nursing discharge note of older patients transferred from hospital to home care is incomplete and are influenced by patient and transfer characteristics. In order to ensure continuity and appropriate nursing follow-up care, we emphasize the need for a more comprehensive approach to older patients, and that this must be reflected in the nursing discharge note.

1. INTRODUCTION

Older people are considered especially vulnerable during care transfers, as they often have complex care needs caused by multimorbidity and multiple functional limitations [1-4]. The fact that older people tend to have more frequent hospital admissions [5] and use a greater array of other health care services [6], implies that they also experience a greater number of care pathways across health care organizations. Communication of both physical and mental health status of older patients transferred between providers is important because change in condition can be a sign of acute disease [7-9], and physical and mental failure necessitate specific approaches to clinical care [10,11]. Although follow-up care of older patients after hospital discharge might be influenced by the information conveyed by the referring provider [12, 13], there have been many studies showing incompleteness and inaccuracy in the information exchanged, for example, activity of daily living [14], mental status [15, 16], communication ability [17], nutrition status and eating ability [18], medication [19-21], and psychosocial status [22,23]. The current paper reports a study that is part of a larger research project dealing with nurses’ information exchange during older people transfer between hospital and home care.

While researchers worldwide have expressed concern about the fragmentation of health care [24-27], there have been increasing focus on the importance of continuity of care in improving preventive care, lower rates of hospitalizations, and patient outcomes and satisfaction [28-33]. Many efforts have been made to clarify the concept of continuity of care [34,35]. A widely used framework, introduced by Haggerty et al. [36] and later adopted by Freeman et al. [37], describes three essential types of continuity of care, namely, informational, relational, and management. While the relational type concerns the relationship between the patient and the provider(s), the informational and management types deal with, respectively, the timely availability of relevant information to make current care appropriate for each individual, and the communication of both facts and judgments across providers, and between providers and patients [37]. From this, one can assume that the comprehensiveness and accuracy of the nursing discharge note have an important impact on the informational continuity, and that the extent of planned interventions and described responsibilities for follow-up care in the discharge note influence the management continuity.

The Norwegian government [38,39] has stated that the lack of interaction between the two organizational structures of the health care system, primary and secondary care, represents perhaps the greatest challenge the health service faces, and many national efforts have been made to improve the communication and coordination of health care over the last decades [40]. Since 1999, all health care professionals in Norway, including nurses, have been required to document provided health care in the patient record and to exchange relevant information for enhancing continuity of care [41]. This implies that in case of hospital discharge, a nursing summary (i.e. a discharge note) based on the patient record shall be exchanged to the receiving nurse who needs information to ensure appropriate follow-up nursing care [42]. According to the guidelines [43,44], the nursing discharge note should describe the nursing care delivered, the patient’s health status, and assessments and recommendations for continuing care.

In line with other Nordic countries, many hospitals in Norway use the VIPS model for nursing documentation. The VIPS model (acronym for the four nursing key concept of Well-being, Integrity, Prevention and Security) provides a structure for the content of nursing documentation with keywords on two levels, based on the concept of the nursing process, and with the aim of supporting the systematic documentation of nursing care and promoting individualized care [45,46]. The keywords function as headings beneath which sufficient information is gathered. The first level of keywords consist of the main keywords: nursing history, nursing status, nursing diagnosis, nursing goal, nursing intervention, nursing outcome, and nursing discharge report. The second level include three of the main keywords: nursing history, nursing status, and nursing intervention, which are subdivided into specifying keywords that guide the nursing documentation in details.

Studies have shown that nurses record the initial assessment of the patient to a great extent [47,48], but fail to make care plans including goals for nursing care, and planned and implemented interventions and outcomes of care [49-51]. To a large extent nursing interventions are noted in most of the records without being connected to a systematic plan [48]. Rather than document patient care by following a logic structure according to the nursing process, they document chronologically along a time axis [52]. Furthermore, nurses have been accused of being too focused on describing their tasks in the documentation rather than describing the patients’ needs and experiences [53,54], and that they document physical care more often than other caring dimensions [22,54,55]. However, a study has shown that nurses document more psychosocial care after integrating an electronic nursing discharge note with structured templates in the EPR [56].

To our knowledge, no previous studies have investigated the relationship between the content of nursing discharge notes and characteristics of patient and transfer. A better understanding of the nurses’ exchange of written patient information at discharge of older people from hospital to home care could support nurses in improving the continuity of care and promote a safe patient transfer.

Aim and Research Questions

The aims of the study were to: 1) examine the content of nurses’ discharge notes of older patients’ discharged from hospital to home care, and 2) to investigate the association between the content of discharge notes and characteristics of patient and transfer. The following specific research questions were investigated:

• To what extent are VIPS keywords used in the nursing discharge note?

• Are there differences in VIPS keywords used in the discharge note in relation to patient and transfer characteristics?

• Is there an association between the content of VIPS keywords in the nursing discharge note and patient and transfer characteristics?

2. METHOD

2.1. Setting and Participants

This paper reports a study that is part of a larger research project dealing with nurses’ information exchange during older people transfer between hospital and home care. Using convenience sampling, nursing documentation from a total of 102 older inpatient records was collected from the general medicine ward and a geriatric unit at a local hospital in central Norway during 2010-2011. Seventy of these records included nursing discharge notes which were included in the present study. Inclusion criteria of the patients were as follows: 70+ years of age, consent competent, and admitted from home care and discharged back to their home after the hospital treatment. The selection of participants who met these criteria was made by the nursing managers at the respective units. Written informed consent was obtained from the participants after receiving a written and oral explanation of the study communicated by the nursing managers.

2.2. Data Collection

Nursing discharge notes and background data were retrieved and de-identified by the nursing managers on the day of discharge. At the hospital, the nursing discharge note was an integrated part of the nursing documentation in the Electronic Patient Record (EPR) system, Doculive©. When patients were discharged from the hospital, a paper version of the nursing discharge note in the EPR was exchanged to the home care. The design of the nursing discharge note comprised two main sections. The first section contained predefined information, where the EPR system automatically generates some information elements when a nurse creates a nursing discharge note for a specific patient, including the unit’s name, the patient’s name, date of birth, and the name of the nurse who wrote and approved the discharge note. The second section, “patient’s current status”, was open for the nurses to record free text. However, this section were structured in accordance with the VIPS model [45], i.e. the nurses chose relevant keywords from all possible keywords on the second level in the model, including communication, cognition/development, breathing/circulation, nutrition, elimination, skin/integument, activity, sleep, pain/perception, sexuality/reproduction, psychosocial (emotional and relational), spiritual/cultural, wellbeing, and composite assessment. Only this second section of the discharge note was included for further investigations. Background data was used to identify patient and transfer characteristics, and included age, gender, living situation, housing situation, distance from hospital, type of hospitalization, status of readmission (within 30 days after discharge), medical department facility, and length of hospital stay.

2.3. Measures

For measuring the extent of used VIPS keywords under the heading “patient’s current status”, a summative scale was created based on all the 15 items (keywords). Discharge notes including all items scored the maximum of 15, while those who did not include any items at all scored the minimum of 0.

Based on theoretical considerations and the results from reliability tests, two scales were formed to measure in the extent to which mental and physical related VIPS keywords were used. The indexes were labeled and valued as follows: Physical related keywords scale (Cronbach’s α = 0.80) included the items breathing/circulation, nutrition, elimination, and activity. Discharge notes including all items scored the maximum of 4, while those who did not include any items at all scored the minimum of 0. Mental related keywords scale (Cronbach’s α = 0.75) included the items communication, cognition/development, sleep, and pain/perception, psychosocial/ emotional, and psychosocial/relational. Discharge notes including all items scored the maximum of 6, while those who did not include any items at all scored the minimum of 0.

2.4. Data Analysis

The SPSS version 17.0 for Windows program (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA) was employed for statistical analysis. Frequencies were used to describe patient and transfer characteristics, and content of the transfer documents. Mean (M), standard deviations (SD) and independent sample t-tests were performed to show and examine differences in VIPS keywords used in the discharge note in relation to patient and transfer characteristics. To examine if physical and mental related keywords could be predicted by patient and transfer characteristics, linear multiple regression analysis were used. Physical related keywords scale and mental related keywords scale were used as dependent variables, representative, and patient characteristics and transfer characteristics as the independent variables. Prior to undertaking the analysis, a number of assumptions of regression were explored. The predictor variables were selected based on the results of the independent sample t-tests as well as review of previous literature. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. There was no evidence of multicollinearity among tested covariates (VIF < 1.1).

2.5. Ethical Considerations

The research project was approved by The Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics of Norway (nr 2009/815) and carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki [57]. Permission to perform data collection in the hospital wards was obtained from the hospital research unit. All patients gave written informed consent after explanations of the study. No identifying information about the patients was available to the researchers.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Characteristics of the Sample

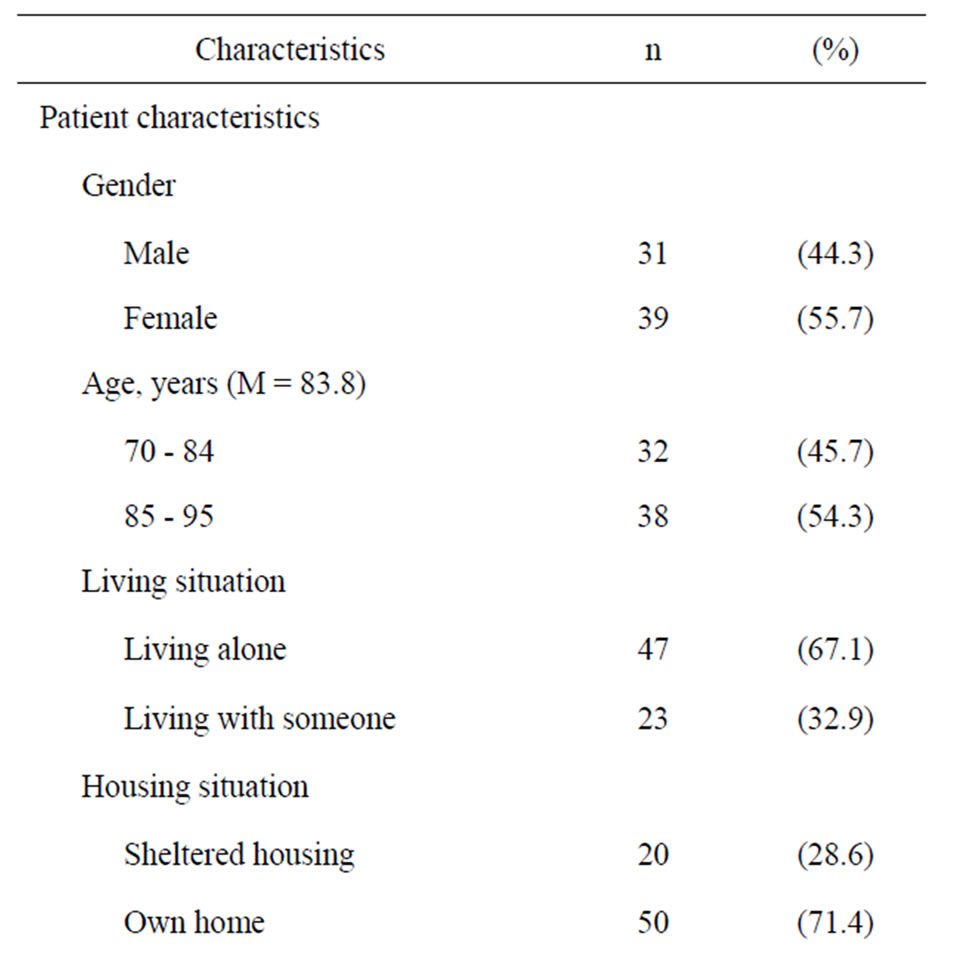

Characteristics of the patients and transfers are shown in Table 1. A total of 70 hospitalizations of home care patients were included, 41 from a general medicine ward and 29 from a geriatric unit. The mean age was 83.8 years (range 70 - 95) and 55.7% were female. Most of the patients lived alone (67.1%) and in their own homes (71.4%). Pneumonia was the most common reason for hospitalization (34.3%), followed by anemia (10.0%), repeated falls (8.6%), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (5.7%), syncope (5.7%), and myocardial infarction (5.7%). About eighty-three percent of transfers were

Table 1. Characteristics of the sample (N = 70).

considered urgent. The median length of hospital stay was 7 days (range 1 to 29). Twenty-four percent of the transfers were hospital readmissions within 30 days of return to the home care.

3.2. Patient and Transfer Characteristics and VIPS Keywords Used in the Nursing Discharge Note

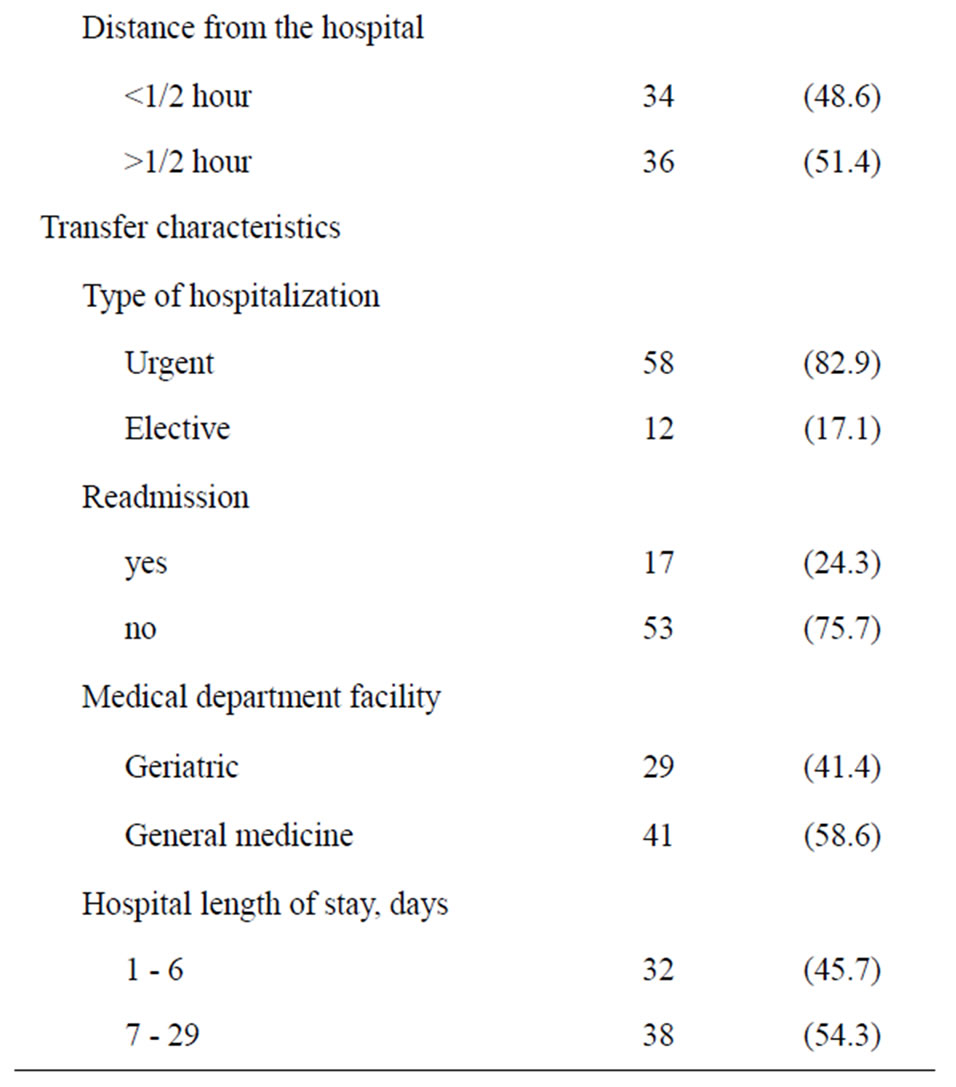

The frequencies of VIPS keywords used in the discharge note are shown in Table 2. The most frequently used keywords were “nutrition” and “activity” (95.7%). There was no information at all in any of the discharge notes about “sexuality/reproduction” and “spiritual/cultural”. Keywords related to physical health were most frequently used, while keywords related to psychosocial situation and level of well-being were less used.

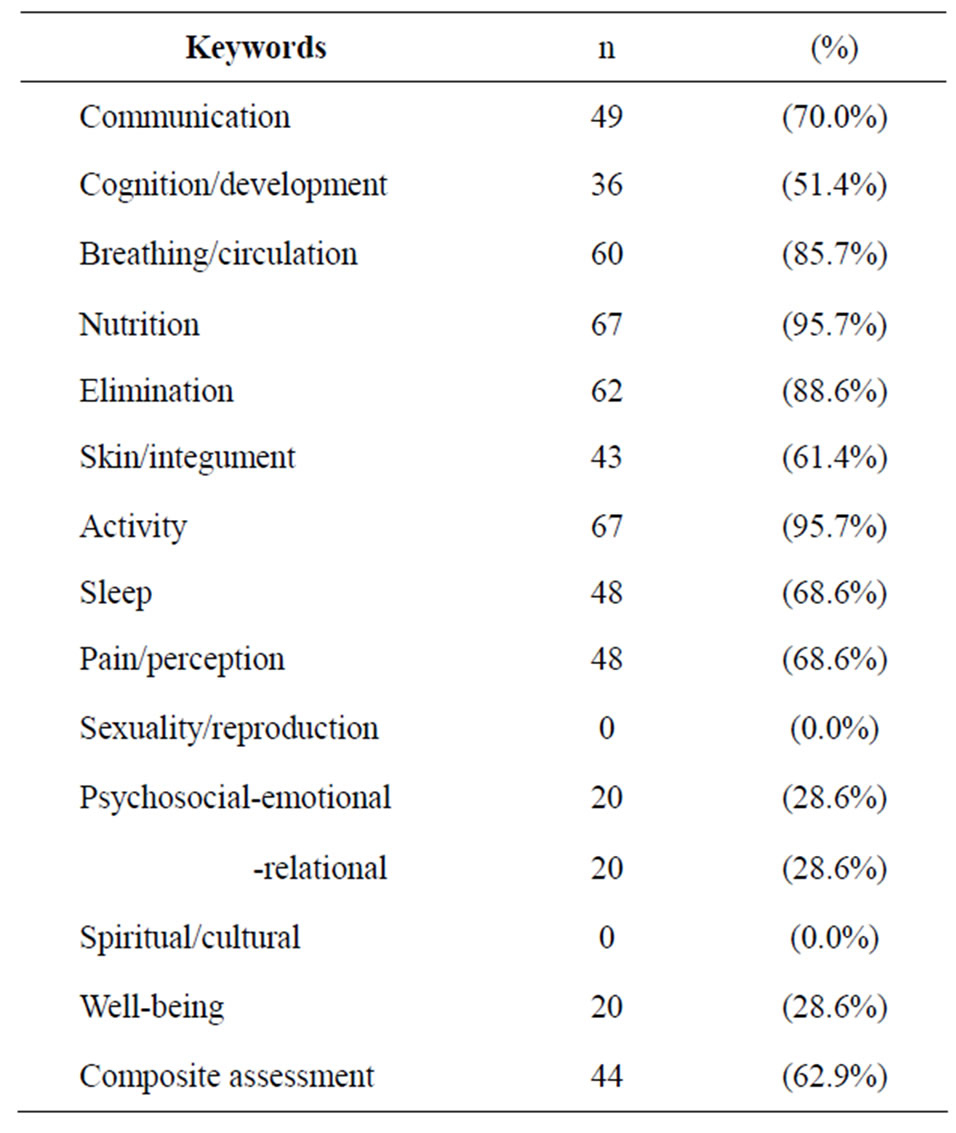

Table 3 shows the differences between the mean scores according to patient and transfer characteristics. The mean score for the extent of used VIPS keywords was 6.66 (of maximum 15, SD 2.88). Significant difference was found for gender (p < 0.05), where discharge notes of females had a higher total mean score on the extent of used VIPS keywords than of male. There was a strong trend (p = 0.06) for the geriatric unit to use more VIPS keywords than the general medicine ward. In addition, a trend was found for housing situation (p = 0.08), where discharge notes of patients living in sheltered housing had a slightly higher score than discharge notes

Table 2. Frequencies of used VIPS keywords in the nursing discharge note (N = 70).

Table 3. Differences between mean scores for the extent of used VIPS keywords according to patient and transfer characteristics (N = 70).

of patients living in their own homes. The mean score for mental related VIPS keywords was 2.84 (of maximum 6, SD 1.87). Significant differences were found for gender (p < 0.001), age (p < 0.05) and medical department facility (p < 0.001), where a higher score was found for discharge notes of females, patients in the oldest age group, and patients hospitalized at the geriatric unit. The mean score for physical related VIPS keywords was 0.34 (of maximum 4, SD 0.88). Significant difference was found for medical department facility (p < 0.05), were discharge notes of patients at a general medicine ward had a higher score of physical related VIPS keywords.

3.3. Association of Patient and Transfer Characteristics and Used VIPS Keywords

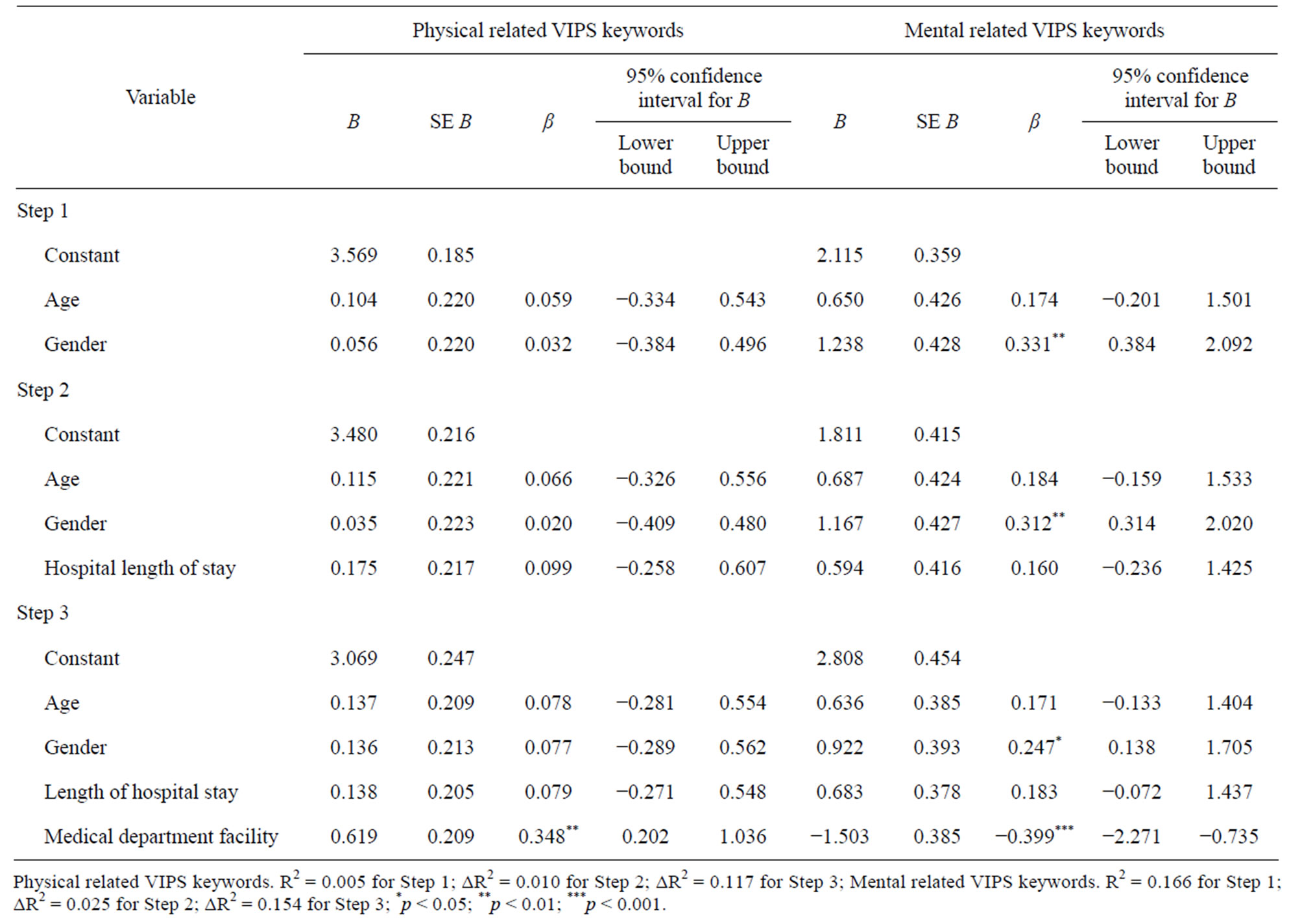

Table 4 shows results of two linear multiple regression analysis examining factors associated with the presence of, respectively, physical related and mental related VIPS keywords in the nursing discharge note. Predictor variables, including age, gender, medical department facility, and length of hospital stay, were entered in three steps. At Step 1, age and gender were entered. At Step 2, length of hospital stay was added and, at Step 3, medical department facility was added. The results show that medical department facility was the only significant predictor of physical related keywords in the discharge note. The model explained 11.7 percent of the variance. For the mental related keywords, gender and medical department facility were significant predictors of mental related keywords in the discharge note, where the largest predictor was medical department facility. Overall 15.4 percent of the variance was explained by the model.

4. DISCUSSION

The aims of the study were twofold: to examine the content of nurses’ discharge notes of older patients’ discharged from hospital to home care, and to investigate the association between the content of discharge notes and characteristics of patient and transfer.

Considering the sample of discharge notes as a whole, the most frequently used keywords were related to physical health, while information concerning psychosocial status and well-being were less used. This finding is somewhat in contrast with the findings of Hellesø [56], who found that nurses used the keyword “psychosocial” just as much as for example “breathing/circulation” in the discharge note. An explanation could be that the study performed by Hellesø took place during implementation of EPR, which could have caused a novelty effect and strong motivation and positive attitudes among the nurses to improve the documentation. The fact that neither the keyword “sexuality/reproduction” nor the keyword “spiritual/cultural” were represented in our sample is in accordance with previous studies [22,55]. The favoring of the physical dimension in nursing documentation may be reflecting a lack of knowledge and skills in responding to other caring needs in actual nursing practice. In a study in long-term geriatric care,

Table 4. Linear multiple regression for variables predicting presence of VIPS keywords in the nursing discharge note.

the nurses considered their capacity to meet the psychosocial needs of older people (e.g. to face death, express sexuality, or discuss anxiety-provoking or difficult matters) as less adequate compared with the physical needs [58]. A major focus on physical health in the documentation may also be explained by biomedical overlay in the context of hospital care. Hyde et al. [54] found that nursing documentation in the hospital patient record was dominated with instrumental rationality, the “voice of medicine”, including a great amount of medico-technical details primarily related to the physiological status of the patient at the expense of information regarding the patient’s feelings, emotions, and experience of illness. Findings from a qualitative metasynthesis made by Kärkkäinen et al. [53] indicates that lack of focus on the patients experiences in the nursing documentation is due to the nurses propensity to describe the patients problems and needs without conferring the patient.

A consequence of inadequate information about the patient’s mental health status in the discharge note may be that home care nurses, in ignorance of mental failure in the patients, are unable to deliver appropriate care to their specific needs. In our sample, most of the older patients lived alone in their own homes, which means that they did not have any relatives who could contribute with essential information to the home care nurses. In that way, undocumented symptoms of delirium, for example, could further result in poorer cognitive and functional status, increased morbidity and mortality, and need for institutional care for the older patient [9].

An interesting finding in our study was that discharge notes of females were significantly more likely to include VIPS keywords in general. Seen in relation to the fact that nurses experience female patients to be more demanding and time-consuming than male patients [59], one can speculate that nurses thereby give priority to providing and documenting care to female patients. Discharges notes of females also had a higher score on used mental related keywords, which may be explained by the nurses experience of women as more eager to talk about their feelings and illness [59].

Another finding in our study was that discharge notes of patients at the geriatric unit were more likely to include VIPS keywords in general, and mental related keywords in special, compared to the general medicine ward. An explanation for this difference could be that transitional care, including communication between providers, is recognized as a core competency in geriatric care [60,61]. Presence of more skilled and motivated nurses in geriatric in-hospital care [62] could be another explanation. At the current hospital unit, several nurses had geriatric nursing education. However, the level of motivation and skills among nurses does not depend on educational knowledge only. The current geriatric unit is organized as an interdisciplinary team (i.e. geriatrician, nurse, physiotherapist, and occupational therapist), which implies a comprehensive approach to patient centered care where staff can combine skills, experience, and knowledge to provide favorable clinical outcomes [63, 64]. The fact that the geriatric unit is manned by a small group of staff may also have an impact, as many studies have reported that smaller teams have higher levels of participation which is correlated with effectiveness [63]. While general medicine inpatients often have a specific diagnosis, older people admitted to the geriatric unit commonly have complex needs, multimorbidity, and multiple functional limitations. Thus, the comprehensive geriatric assessment is a common approach used at geriatric specialties, a process that includes determining of the patients medical, functional, psychosocial, and environmental resources and problems, and which ends up in creating a plan for treatment and follow-up care [65]. It is reasonable to suggest that this approach, with its focus on the overall situation of the patient, may be reflected in the nurses’ documentation. Thus, it can be one explanation of why nurses at a geriatric unit use more mental related keywords in the discharge note. Following this line of thought, the high use of physical related keywords among nurses at a general medicine ward could be explained by biomedical overlay, i.e. a narrow focus on physical symptoms where the patient’s body is reduced to its parts [54].

Considering the fact that informational continuity of care is especially important for the oldest of the old, it was encouraging to note that discharge notes of patients in the oldest age group were more likely to include mental related keywords. An explanation to this finding could be the fact that the prevalence of depression [66], delirium [9], and dementia disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease [67], increases significantly with age.

The small sample size (n = 70) and the use of convenience sampling limits the generalizability of the results in this study. Although the patients in the sample were representative of those in the hospital in terms of demographic characteristics such as age and gender, a selection bias may have occurred because patients who had cognitive impairments (e.g. dementia) were excluded due to the requirements of informed consent. Thus, our findings must be viewed in light of the study sample, i.e. older patients who are consent competent. Another limitation is the fact that we had no opportunity to perform drop-out-analysis of those patients who did not volunteer for the study (cf. The Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics). However, according to the nurse managers who were responsible for the recruitment, only a few patients who met the inclusion criteria declined to participate in the study.

The fact that the content of the nursing discharge note in this study was measured by counting VIPS keywords used as headings should be taken into account when interpreting the results. Our data cannot tell us whether the nurses have been true to the guidelines of the VIPS model, i.e. whether they have chosen the relevant heading for the free text they have recorded. Studies have shown that nurses tend to group their documentation under the wrong keywords [50,55]. For example, Gunhardsson et al. [55] found that to some extent information that should have been documented under the keyword “psychosocial” was documented under “well-being”. In our study, the keyword “well-being” was not included in the scale used to measure mental related keywords. From this, one can speculate about how well we have measured what we have intended to measure. However, the Cronbach’s α for both scales made for this study were high (Cronbach’s α = 0.75 - 0.80), which indicates strong internal consistency reliability.

We should also note that other patient and transfer characteristics (e.g. function status and frequency of assistance provided by home care services) not included in this study might also influence the content of the discharge note. Similarly, characteristics of the nurse and clinical contexts might be of importance. However, such data were unavailable to us, and therefore we could not evaluate the possible impact of these factors.

5. CONCLUSION

The result of this study indicate that documentation of patient status in the nursing discharge note of older patients transferred from hospital to home care does not address all dimensions of care, is incomplete when assessed according to the VIPS model, and are influenced by patient and transfer characteristics. In order to ensure continuity and appropriate nursing follow-up care after transfer, we emphasize the need for a more comprehensive approach to older patients, and that this must be reflected in the nursing discharge note.

REFERENCES

- Marengoni, A., Angleman, S., Melis, R., Mangialasche, F., Karp, A., Garmen, A., Meinow, B. and Fratiglioni, L. (2011) Aging with multimorbidity: A systematic review of the literature. Ageing Research Reviews, 10, 430-439. doi:10.1016/j.arr.2011.03.003

- Nardi, R., Scanelli, G., Corrao, S., Iori, I., Mathieu, G. and Amatrian R.C. (2007) Co-morbidity does not reflect complexity in internal medicine patients. European Journal of Internal Medicine, 18, 359-368. doi:10.1016/j.ejim.2007.05.002

- Reed, J., Cook, G., Childs, S. and McCormack, B. (2005) A literature review to explore integrated care for older people. International Journal of Integrated Care, 5. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=16773170

- Coleman, E.A. (2003) Falling through the cracks: Challenges and opportunities for improving transitional care for persons with continuous complex care needs. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 51, 549-555. doi:10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51185.x

- Condelius, A., Edberg, A.K., Jakobsson, U. and Hallberg, I.R. (2008) Hospital admissions among people 65+ related to multimorbidity, municipal and outpatient care. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 46, 41-55. doi:10.1016/j.archger.2007.02.005

- Vogeli, C., Shields, A.E., Lee, T.A., Gibson, T.B., Marder, W.D., Weiss, K.B. and Blumenthal, D. (2007) Multiple chronic conditions: Prevalence, health consequences, and implications for quality, care management, and costs. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 22, 391-395. doi:10.1007/s11606-007-0322-1

- Gray, L.K., Smyth, K.A., Palmer, R.M., Zhu, X. and Callahan, J.M. (2002) Heterogeneity in older people: Examining physiologic failure, age, and comorbidity. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 50, 1955-1961. doi:10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50606.x

- Chong, C.P. and Street, P.R. (2008) Pneumonia in the elderly: A review of the epidemiology, pathogenesis, microbiology, and clinical features. Southern Medical Journal, 101, 1141-1145. doi:10.1097/SMJ.0b013e318181d5b5

- Cerejeira, J. and Mukaetova-Ladinska, E.B. (2011) A clinical update on delirium: From early recognition to effective management. Nursing Research and Practice, 2011. doi:10.1155/2011/875196

- Ornstein, K., Smith, K.L., Foer, D.H., Lopez-Cantor, M.T. and Soriano, T. (2011) To the hospital and back home again: A nurse practitioner-based transitional care program for hospitalized homebound people. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 59, 544-551. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03308.x

- Boling, P.A. (2009) Care transitions and home health care. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine, 25, 135-148. doi:10.1016/j.cger.2008.11.005

- Kripalani, S., Jackson, A.T., Schnipper, J.L. and Coleman, E.A. (2007) Promoting effective transitions of care at hospital discharge: A review of key issues for hospitalists. Journal of Hospital Medicine, 2, 314-323. doi:10.1002/jhm.228

- Coleman, E.A., Min, S.J., Chomiak, A. and Kramer, A.M. (2004) Posthospital care transitions: Patterns, complications, and risk identification. Health Services Research, 39, 1449-1466. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00298.x

- Garasen, H. and Johnsen, R. (2007) The quality of communication about older patients between hospital physicians and general practitioners: A panel study assessment. BMC Health Services Research, 7, 133. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-7-133

- Brown, E.L., Raue, P.J., Mlodzianowski, A.E., Meyers, B.S., Greenberg, R.L. and Bruce, M.L. (2006) Transition to home care: Quality of mental health, pharmacy, and medical history information. The International Journal of Psychiatry Medicine, 36, 339-349. doi:10.2190/6N5P-5CXH-L750-A8HV

- Boockvar, K.S., Fridman, B. and Marturano, C. (2005) Ineffective communication of mental status information during care transfer of older adults. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 20, 1146-1150. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.00262.x

- Cwinn, M.A., Forster, A.J., Cwinn, A.A., Hebert, G., Calder, L. and Stiell, I.G. (2009) Prevalence of information gaps for seniors transferred from nursing homes to the emergency department. Canadian Journal of Emergency Medicine, 11, 462-471.

- Carlsson, E., Ehnfors, M., Eldh, A.C. and Ehrenberg, A. (2012) Accuracy and continuity in discharge information for patients with eating difficulties after stroke. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 21, 21-31. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03648.x

- Coleman, E.A., Smith, J.D., Raha, D. and Min, S.-J. (2005) Posthospital medication discrepancies: Prevalence and contributing factors. Archives of Internal Medicine, 165, 1842-1847. doi:10.1001/archinte.165.16.1842

- Glintborg, B., Andersen, S.E. and Dalhoff, K. (2007) Insufficient communication about medication use at the interface between hospital and primary care. Quality & Safety in Health Care, 16, 34-39. doi:10.1136/qshc.2006.019828

- Mesteig, M., Helbostad, J.L., Sletvold, O., Rosstad, T. and Saltvedt, I. (2010) Unwanted incidents during transition of geriatric patients from hospital to home: A prospective observational study. BMC Health Services Research, 10, 1. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-10-1

- Helleso, R., Lorensen, M. and Sorensen, L. (2004) Challenging the information gap—The patients transfer from hospital to home health care. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 73, 569-580. doi:10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2004.04.009

- Anderson, M.A., Helms, L.B., Black, S. and Myers, D.K. (2000) A rural perspective on home care communication about elderly patients after hospital discharge. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 22, 225-243. doi:10.1177/019394590002200208

- Waibel, S., Henao, D., Aller, M.-B., Vargas, I. and Vázquez, M.-L. (2012) What do we know about patients’ perceptions of continuity of care? A meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. International Journal of Quality in Health Care, 24, 39-48. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzr068

- Bodenheimer, T. (2008) Coordinating care—A perilous journey through the health care system. New England Journal of Medicine, 358, 1064-1071. doi:10.1056/NEJMhpr0706165

- Mur-Veeman, I., Van Raak, A. and Paulus, A. (2008) Comparing integrated care policy in Europe: Does policy matter? Health Policy, 85, 172-183. doi:10.1016/j.healthpol.2007.07.008

- Schoen, C., Osborn, R., Squires, D., Doty, M.M., Pierson, R. and Applebaum, S. (2011) New 2011 survey of patients with complex care needs in eleven countries finds that care is often poorly coordinated. Health Affairs, 30, 2437-2448. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0923

- Van Servellen, G., Fongwa, M. and D’Errico, E.M. (2006) Continuity of care and quality care outcomes for people experiencing chronic conditions: A literature review. Nursing Health Science, 8, 185-195. doi:10.1111/j.1442-2018.2006.00278.x

- Saultz, J.W. and Lochner, J. (2005) Interpersonal continuity of care and care outcomes: A critical review. The Annals of Family Medicine, 3, 159-166. doi:10.1370/afm.285

- Van Walraven, C., Oake, N., Jennings, A. and Forster, A.J. (2010) The association between continuity of care and outcomes: A systematic and critical review. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 16, 947-956. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2753.2009.01235.x.

- Hadjistavropoulos, H.D., Garratt, S., Janzen, J.A., Bourgault-Fagnou, M.D. and Spice, K. (2009) Development and evaluation of a continuity of care checklist for improving orthopaedic patient discharge from hospital. Journal of Orthopaedic Nursing, 13, 183-193. doi:10.1016/j.joon.2009.05.006

- Cabana, M.D. and Jee, S.H. (2004) Does continuity of care improve patient outcomes? The Journal of Family Practice, 53, 974-980.

- Worrall, G. and Knight, J. (2006) Continuity of care for older patients in family practice: How important is it? Canadian Family Physician, 52, 754-755.

- Parker, G., Corden, A. and Heaton, J. (2011) Experiences of and influences on continuity of care for service users and carers: Synthesis of evidence from a research programme. Health & Social Care in the Community, 19, 576-601. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2524.2011.01001.x

- Heaton, J., Corden, A. and Parker, G. (2012) “Continuity of care”: A critical interpretive synthesis of how the concept was elaborated by a national research programme. International Journal of Integrated Care, 12. http://www.ijic.org/index.php/ijic/article/view/794

- Haggerty, J.L., Reid, R.J., Freeman, G.K., Starfield, B.H., Adair, C.E. and McKendry, R. (2003) Continuity of care: A multidisciplinary review. British Medical Journal, 327, 1219-1221. doi:10.1136/bmj.327.7425.1219

- Freeman, G.K., Woloshynowych, M., Baker, R., Boulton, M., Guthrie, B., Car, J., Haggerty, J. and Tarrant, C. (2007) Continuity of care 2006: What have we learned since 2000 and what are policy imperatives now? Report for the National Co-ordinating Centre for NHS Service Delivery and Organisation R & D (NCCSDO), Imperial College London, London.

- Norwegian Ministry of Health and Care Services (2008) Stortingsmelding nr. 47 (2008-2009), Samhandlingsreformen. Rett behandling—på rett sted—til rett tid (The Coordination Reform. Proper treatment—At the right place and right time. Report No. 47 (2008-2009) to the Storting) [in Norwegian]. Norwegian Ministry of Health and Care Services, Oslo.

- Norwegian Ministry of Health and Care Services (2011) Nasjonal helseog omsorgsplan (2011-2015) [National health and care plan (2011-2015)] [in Norwegian]. Norwegian Ministry of Health and Care Services, Oslo.

- Romøren, T.I., Torjesen, D.O. and Landmark, B. (2011) Promoting coordination in Norwegian health care. International Journal of Integrated Care, 11. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=22128282

- Norwegian Ministry of Health and Care Services (1999) Lov om helsepersonell av 2.juli 1999 nr 64. Helsepersonelloven (Act of 2 July 1999 No. 64 relating to health personnel etc. The health personnel act) (in Norwegian). Norwegian Ministry of Health and Care Services, Oslo.

- Norwegian Ministry of Health and Care Services (2000) Forskrift om pasientjournal (The Norwegian patient record regulation) (in Norwegian). Norwegian Ministry of Health and Care Services, Oslo.

- The Norwegian Nursing Organisation (NSF) (2007) Dokumentasjon av sykepleie i elektronisk pasientjournal (Documenting nursing care in an electronic patient record) (In Norwegian). The Norwegian Nursing Organisation (NSF), Oslo.

- Bach, G. and KITH (2003) Kravspesifikasjon for elektronisk dokumentasjon av sykepleie (Requirements specification for electronic documentation of nursing. National standard) (in Norwegian). KITH Report R 12/03 Norwegian Centre for Informatics in Health and Social Care, Oslo. http://www.kith.no/upload/1101/R12-03DokumentasjonSykepleie-rev1_1-NasjonalStandard.pdf

- Ehrenberg, A., Ehnfors, M. and Thorell-Ekstrand, I. (1996) Nursing documentation in patient records: Experience of the use of the VIPS model. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 24, 853-867. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.1996.26325.x

- Ehnfors, M., Thorell-Ekstrand, I. and Ehrenberg, A. (1991) Towards basic nursing information in patient records. Vård i Norden, 11, 12-31.

- Ehrenberg, A., Ehnfors, M. and Ekman, I. (2004) Older patients with chronic heart failure within Swedish community health care: A record review of nursing assessments and interventions. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 13, 90-96. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2702.2003.00837.x

- Törnvall, E., Wilhelmsson, S. and Wahren, L.K. (2004) Electronic nursing documentation in primary health care. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Science, 18, 310-317. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6712.2004.00282.x

- Ehrenberg, A. and Birgersson, C. (2003) Nursing documentation of leg ulcers: Adherence to clinical guidelines in a Swedish primary health care district. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Science, 17, 278-284. doi:10.1046/j.1471-6712.2003.00231.x

- Rykkje, L. (2009) Implementing Electronic Patient Record and VIPS in medical hospital wards: Evaluating change in quantity and quality of nursing documentation by using the audit instrument Cat-ch-Ing. Vård i Norden, 29, 9-13.

- Häyrinen, K., Lammintakanen, J. and Saranto, K. (2010) Evaluation of electronic nursing documentation—Nursing process model and standardized terminologies as keys to visible and transparent nursing. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 79, 554-564. doi:10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2010.05.002

- Gjevjon, E.R. and Helleso, R. (2010) The quality of home care nurses’ documentation in new electronic patient records. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 19, 100-108. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.02953.x

- Kärkkäinen, O., Bondas, T. and Eriksson, K. (2005) Documentation of individualized patient care: A qualitative metasynthesis. Nursing Ethics, 12, 123-132. doi:10.1191/0969733005ne769oa

- Hyde, A., Treacy, M.P., Scott, P.A., Butler, M., Drennan, J., Irving, K., Byrne, A., MacNeela, P. and Hanrahan, M. (2005) Modes of rationality in nursing documentation: Biology, biography and the “voice of nursing”. Nursing Inquiry, 12, 66-77. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1800.2005.00260.x

- Gunhardsson, I., Svensson, A. and Berterö, C. (2008) Documentation in palliative care: Nursing documentation in a palliative care unit—A pilot study. The American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Care, 25, 45-51. doi:10.1177/1049909107307381

- Hellesø, R. (2006) Information handling in the nursing discharge note. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 15, 11-21. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2005.01235.x

- World Medical Association (2008) World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects.

- Isola, A., Backman, K., Voutilainen, P. and Rautsiala, T. (2008) Quality of institutional care of older people as evaluated by nursing staff. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 17, 2480-2489. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2007.01951.x

- Foss, C. and Sundby, J. (2003) The construction of the gendered patient: Hospital staff’s attitudes to female and male patients. Patient Education and Counseling, 49, 45-52. doi:10.1016/S0738-3991(02)00039-3

- Norwegian Directorate of Health (2007) Respekt og kvalitet: Rapport om styrking av spesialisthelsetjenester for eldre (Respect and quality: Report on strengthening health services for the elderly) (in Norwegian). Norwegian Directorate of Health, Oslo.

- Coleman, E.A. and Boult, C. (2003) Improving the quality of transitional care for persons with complex care needs. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 51, 556-557. doi:10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51186.x

- Bo, M., Martini, B., Ruatta, C., Massaia, M., Ricauda, N.A., Varetto, A., Astengo, M. and Torta, R. (2009) Geriatric ward hospitalization reduced incidence delirium among older medical inpatients. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 17, 760-768. doi:10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181a315d5

- Xyrichis, A. and Lowton, K. (2008) What fosters or prevents interprofessional teamworking in primary and community care? A literature review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 45, 140-153. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2007.01.015

- Geriatrics Interdisciplinary Advisory Group (2006) Interdisciplinary care for older adults with complex needs: American Geriatrics Society position statement. Journal of American Geriatric Society, 54, 849-852. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00707.x

- Ellis, G., Whitehead, M.A., Robinson, D., O’Neill, D. and Langhorne, P. (2011) Comprehensive geriatric assessment for older adults admitted to hospital: Meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. British Medical Journal, 343, d6553. doi:10.1136/bmj.d6553

- Grav, S., Hellzèn, O., Romild, U. and Stordal, E. (2012) Association between social support and depression in the general population: the HUNT study, a cross-sectional survey. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 21, 111-120. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03868.x

- Jellinger, K.A. and Attems, J. (2010) Prevalence of dementia disorders in the oldest-old: An autopsy study. Acta Neuropathologica, 119, 421-433. doi:10.1007/s00401-010-0654-5

NOTES

*Corresponding author.