Intelligent Information Management

Vol.2 No.4(2010), Article ID:1715,10 pages DOI:10.4236/iim.2010.23029

Transition Process in the Western Balkans: How Much Successful Is This Story?

University of Zagreb, School of Economics and Business, Zagreb, Croatia

E-mail: lskuflic@efzg.hr

Received October 21, 2009; revised January 3, 2010; accepted February 20, 2010

Keywords: The Western Balkans, Transition process; Transition crisis; Macroeconomic indicators; Economic development

Abstract

The last enlargement of the European Union put Western Balkans countries into focus of integration, and thus the countries became an area where future integration is expected. Future enlargement of the European Union depends on the success of the previous European Union accession, as well as on the achieved results of the transition process in the Western Balkans, since these countries are not on the same level as the developed European countries or new member states. The region contains small countries that are at different stages on their road towards membership. Transition is a comprehensive process of economic and political reforms that creates many shocks in the economy, and when this process occurs in a politically unstable and war environment, as the case being with the Western Balkans, the results may be very unfavorable. Formal agreements improved the relations between these countries and the European Union, thereby had an influence on risk reduction and increased business transparency, resulting in a growing interest of foreign investors for the region. Despite increased investments in the region and rapid economic growth, Western Balkan countries have only 21% (Albania) and 52% (Croatia) of the average European Union Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita, indicating the need for faster implementation of reforms and individual involvement of countries into the process of European integration. There is a significant development gap between Western Balkan countries, so observing the region as a whole and applying a singular strategy in the sense of its economic leveling and the process of European Union accession would have a negative impact on Croatia, as the most developed country of the region.

1. Introduction

The last enlargement of the European Union, by two new members Bulgaria and Romania, shifted the focus of Union bodies from Southeast Europe towards Western Balkans countries. This area includes countries of the former Yugoslavia; except Slovenia (becomes a member in 2004), with Albania. Western Balkan countries are an extremely politically unstable area where the war was conducting only a few years back, and in some countries there is still a potential danger of further conflicts. At the same time, the economic potential of the area is insufficient, so the European Union is putting in an extra effort to include these countries into the European integration area, since the territory is very close to its border, some countries being its bordering countries.

Western Balkan countries are small national economies, Serbia is the biggest and Montenegro the smallest. The whole region has the population of about 21.5 million, accounting for 1/3 of the total population of 10 new members of the European Union. Region’s GDP is around 94 billion Euros (2007) or 0.5% of the total GDP of the European Union. According to World Bank classification, these countries are lower middle-income countries, except Croatia as an upper middle-income economy.

This paper explores the efficiency of the transition process in the Western Balkans, and after the introduction it will give a theoretical review of transition and the relevant phases of that process regarding the transition from socialist system of central planning to market economy. The theoretical part presents indicators that will be used to evaluate the process of transition. The third empirical part explores the period immediately before the transition with the focus on the macroeconomic situation after economical and political reform, and the period is shown through the analysis of relevant macroeconomic indicators. In this part, author evaluates the transition in the region through the analysis of transition indicators. The fourth part concentrates on foreign direct investment into Western Balkan region, since foreign investment is one of the determinants for the efficiency of the transition. The final part gives closing considerations.

2. What is the Transition Process?

Transition is a relatively new term in the area of social sciences and includes the processes of pluralisation and democratization in former socialist countries [1], and can be observed, at the same time, from the economical and political point of view. Some countries went through changes in the economy simultaneously with significant changes in the political situation (e.g. political overthrow in Romania, the government collapse in the Soviet Union or declaration of independence by some Western Balkan countries; Slovenia, followed by Croatia, Macedonia, Serbia, Montenegro and most recently Kosovo). From the economic point of view, transition implies the process of transformation of non-market, or centrally planned economy into market economy that became especially popular with the collapse of socialist structure. In general, the aim of the transition is to achieve changes in ownership, to establish the market, companies, stabile macroeconomic environment and political structure [2]; also, another goal is to realize economic liberalization, macroeconomic stabilization, privatization and restructuring of economy in order to establish a strong financial sector which will serve as a foundation for the development of private entrepreneurship.

In the most general sense, transition implies [3]:

• liberalizing economic activity, prices, and market operations, together with reallocating resources to their most efficient use;

• macroeconomic stabilization and developing indirect, market-oriented instruments for that;

• privatization and building the effective enterprises and economic efficiency;

• imposing hard budget constraints, which provides incentives to improve efficiency; and

• establishing an institutional and legal framework to secure property rights, the rule of law, and transparent market-entry regulations.

The transition from centrally-planned to market economy was accompanied by deep and long-term recession, and its duration and depth was longer and deeper than falls in ordinary business cycles of developed countries. “The reason for such instances must be sought in fundamental changes that go hand in hand with the transition, as well as in the changes in the way management is done, i.e. this is the result of the implementation of the necessary transition measures in order to improve the effect both of the market and stabilization programs so to eliminate internal and external imbalance. [4].

Transition crisis occurred in many forms; drastic decrease of GDP, industrial and agricultural production, disinvestment, decrease in monthly wages and salaries, increase of unemployment rates and high inflation rates. Generally speaking, transitional changes lead to growing dissemblance in the distribution of income and wealth. The dynamics and the interrelation of magnitude in a country depended on the reform background and the level of economic development at the beginning of transition [5]. But, the mentioned elements cannot be regarded as determinants of the transition’s success. Namely, Croatia, one of the most successful republics in the former Yugoslavia together with Slovenia, did not reach the expected results of the transition in the foreseen dynamics. The main reason for the slowdown is the war and wartime conditions. In general, aggravating circumstances of transition for most Western Balkan countries were political instability and war conflicts, which had a significant impact on the usual dynamics of the transition from planned to market economy, in a way of slowing it down.

Taking the previous definition of transition as the starting point, the term transitional economy can be applied to the total of 25 countries. Literature dealing with economy mostly mentions the countries of Central and Eastern Europe since having the best results in the process as such, and these countries are the ones that came closest to their aim of a prosperous country of Western European type by joining the EU. But still the term transitional economy can also be applied to some countries outside Europe like China. To some extent, this term can be used for some Asian economies that all well governed, for some post-dictatorial countries of the Latin America and for a certain number of less developed countries of Africa.

2.1. Basic Elements of Economic Policies in Transition Countries

At the beginning of the transition process the basic problem was to choose the optimal transition path from one economic system to the other. Although economic sciences did not take a common stand, in practice two basic solutions were imposed; accomplishing all fundamental transition goals at once and attaining the goals gradually while keeping one or more elements of the previous system. The former has a very negative impact on companies but represents the government as consistent and serious.

The ultimate goal of transition countries was to establish market economy which can vary from one form of welfare state as in the countries of Western Europe, or can take a form of consumerist economy as in the USA or the Far East. If we look at the geographical position, good relations with the European Union and the aspiration towards the integration, transitional economies are oriented towards the welfare state of the European type or certain variations of the welfare state that can be seen in different ratios of market elements and social policies. Emphasizing the social function decreases the competitive abilities of companies, while stressing market elements creates an opposite effect. The answer would be to find an optimal combination. Directing the state towards one of the mentioned prototypes has no significant influence on the goals set. There are some common characteristics that need to be implemented into the economy in order to improve it and for the transition to be successful; they are as follows [6]:

• Basic constitutional rights and the establishment of market-oriented institutions;

• The right of private ownership;

• Competition;

• Stabile national currency;

• High levels of savings;

• Appropriate infrastructure;

• Stabile political system.

A successful implementation of these elements is achieved through:

Macroeconomic stabilization with the aim of removing the macroeconomic imbalance, carry out a transition to budget financing and restrictive monetary and fiscal policies.

Microeconomic liberalization that is price reform, reform of salaries and interest rates, deregulation of commodities market and production factors, liberalization of foreign trade, currency convertibility and reforms to the system of income distribution.

Privatization and structural reform; defining the owners of companies and selling the existing companies, founding new companies, land privatization, privatization of apartments, company restructuring.

Redefining the role of the state in the economic reality or establishing a new and stimulating macroeconomic framework (market-oriented legislation, institutions, etc.).

The targets of macroeconomic stabilization were low inflation and equilibrium of the balance of payments that supports the growth and structural reform. Structural reform improves market mechanisms and functioning of macroeconomic policies and keeps stabilization at higher levels than the real income. Combination of structural reform and stabilization can accelerate growth with the stabilization at higher levels of income. Transition countries which had stronger development performances were slower in the implementation of market-oriented structural reform (e.g. Poland), while countries that did not have very good results in structural reform had considerable difficulties with maintaining stabilization (Bulgaria and Romania).

In general, privatization included four elements: mass privatization in the area of industry; privatization of service industry, agricultural reform and denationalization. In practice, the pattern of mass privatization was the one stressed the most, this pattern was already implemented in Czech Republic, but there was no singular model that could be applied to all countries. Countries differed in strategies and overall results of the privatization process.

At the beginning of the transition process, former socialist countries faced two basic imbalances: internal and external. Different countries resolved these issues in different ways, and their choice of policies depended on nature, size and the length of the imbalance, so:

• Internal imbalance generally requires adaptations of fiscal and monetary policies with the aim of achieving low inflation;

• Countries with stabile balance of payments there is a great possibility to define and implement policies of overvalued exchange rate;

• External imbalance frequently requires adapting the exchange rate;

• As a rule fiscal adaptation is needed, but also various combinations of policies are used.

The existing theoretical solutions, more or less unchanged, were applied to almost all transition countries, but different results were achieved due to different starting position of the economy and different conditions in which transition took place. The complexity of transition process along with the specificity and the diversity of conditions for development have made impossible to generalize or single out one country as a universal model or pattern. A completed pattern or an ideal solution does not exist and cannot be applied to any transitional economy, every country must take into account its own specificity and must start from its own economic potential in the framework of domestic and international environment; thereby find and define its own path of development. But, some achievements and common problems can nonetheless be emphasized.

2.2. Transition Indicators

The success of the implementation of transition processes can be monitored by macroeconomic indicators, and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) developed a set of indicators used for measuring the progress of transition in its report of 1994 (EBRD, 1994). In issues that followed, these indicators were replenished and slightly changed, and today they can be put in four basic groups by which progress is measured in stimulating entrepreneurship, market and trade development, financial institutions and infrastructure. Entrepreneurship is evaluated through large-scale privatization, small-scale privatization, and governance and enterprise restructuring. The level of functioning and trade liberalization is monitored thorough price liberalization, trade and foreign exchange system, and competition policy, while for financial institution evaluation banking reform and interest rate liberalization, and securities markets and non-bank financial institutions are the relevant indicators. The indicator of infrastructure reform is sufficient for the analysis and evaluation of infrastructure of transitional economies. EBRD monitors 29 transition countries through a group of 9 transition indicators.

The above-mentioned indicators can also be monitored by phases, and according to EBRD, there are three phases of transition: market-enabling reforms, market-deepening reforms, and market-sustaining reforms. First phase, market-enabling, of the overall reforms is necessary to allow prices to become the main signal and coordination mechanisms in the economy. Small-scale privatization and liberalization of prices, trade and foreign exchange were the first reforms to be implemented at the beginning of the transition and in mentioned field transition countries had obtained the best results. The transition scores for this reforms show that a large number of transition countries, including some less advanced economies, are close to completing the first phase of entire reforms. For the second phase, market-deepening reforms of financial sector and large-scale privatization, political will should be encouraged with strong institutional reforms. The success of this phase depends on the restructuring of the banking sector and the results achieved by transitional economies differ within certain groups, but if we take a look at our sample of countries, transitional economies are less successful in implementing the second phase of reform that with the first one. Third-phase, market-sustaining reforms, includes governance and enterprise restructuring, and reform to competition policy and infrastructure are in large number of countries at an early stage (EBRD, 2007).

3. Macroeconomic overview of the Western Balkans

3.1. Pre-Transition Period

At the beginning of the transition, the share of GDP derived from private sector activities was small in all transition countries. It ranged from less than 1 percent in the former Czechoslovakia and Russia to almost 20 percent in Poland, compared with about 80 percent in the United States [7]. Economic activity was mostly limited to companies and factories owned by the government, and neither profit nor prices were considered to be determinants of success or a signal for its management, but that was done by political decisions. Since the government decided how produce and allocate the total output, not even the tax system was based on market principles, instead the principle of soft-budget constraint was employed.

National economies developed under mentioned conditions faced many requirements imposed by transition, and if a country had a poor reform background, or if the acountry delayed some of the reforms in order to reduce costs of the transition process, the results were poor. It would be a mistake to compare all transition countries because the starting position of their economies was different, the chosen transition paths were different and there are differences in the environments in which the transition took place. Taking into account the stated facts, international institutions put transition economies into the following groups: countries of Central and Eastern Europe, so there are countries of Central and Eastern Europe that became members of the European Union, Baltic countries and countries of the former Soviet Union, and the countries of the South-East Europe or Western Balkan countries. Literature also shows other classification, but almost all of them are similar to the mentioned one, with smaller variation and some countries are moved into another group.

3.2. Macroeconomic Indicators after 2000

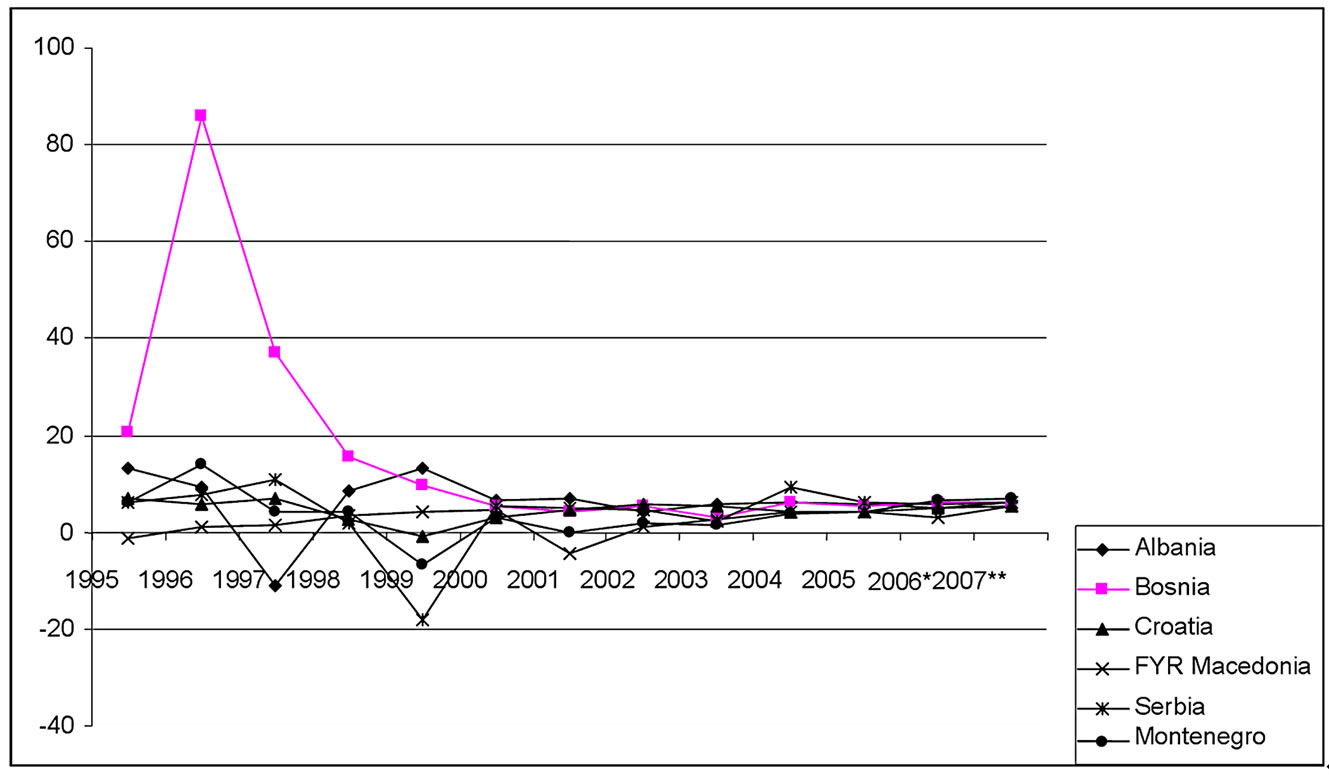

Centrally planned government, a fundamental characteristic of socialism, proved to be inefficient, so the former socialist countries tried to integrate the elements of market economy into their economic systems which caused many problems to which economic sciences could not respond promptly. The generally accepted solution, imposed on transitional economies, was the necessity to remove all socialist elements from the economy and completed implementation of market elements. The result was a transition crisis. Transition crisis can be recognized by the fall in GDP, the decrease in industrial and agricultural production, decrease in investment, a drop in productivity and employment rates, purchasing power loss and high inflation rates [8] in first years of transition. The moment of a turn and gradual resolving of a transition crisis is different from country to country, but in general we can say that there was a positive progress evident in more developed transitional economies of Central and Eastern Europe after 1994, while other countries experienced the same around 1998, but the period in which transition countries in Europe achieved positive rates in a large number of macroeconomic indicators is surely the period after year 2000 (Figure 1). Figure 1 show that the growth rate of the real GDP was positive after 2000 in all Western Balkan countries analyzed, with the exception of Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, which had a fall after the years of positive development cycle.

Namely, after the recovery and the Kosovo crisis, the countries of the region had the average growth of 5 to 6% per year, with the highest average growth rate in Albania –5.8% (for the period 2000-2007), and the lowest in FYR Macedonia.

Figure 1. Growth rate of the real GDP in the Western Balkans, 1995-2007.

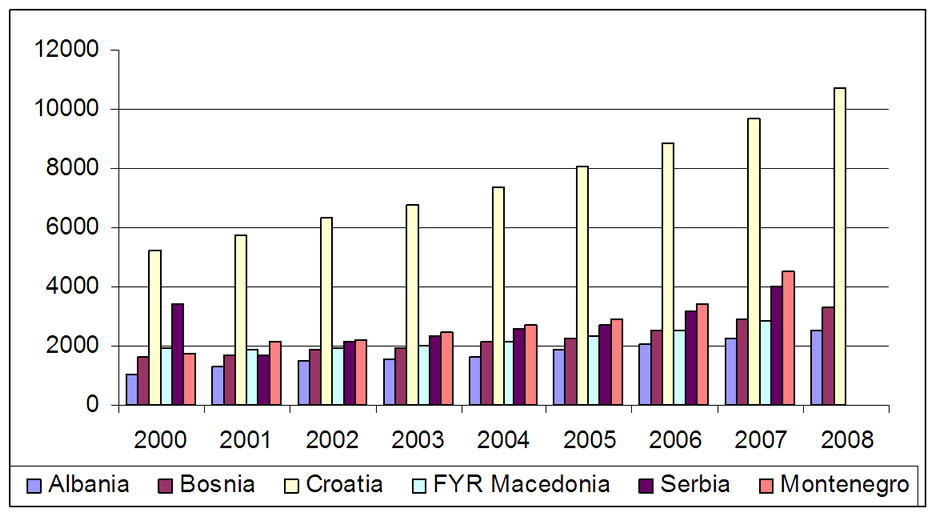

Western Balkan countries are small national economies; Serbia is the biggest with the population of 7.4 million, and Montenegro is the smallest with the population of only 625 thousand, FYR Macedonia has 2 million, and the rest of the countries have between 3 and 4.4 million. From the economic point of view, Croatia is the strongest with the total GDP of 47.4 billion Euros (2008), Serbia follows with 34 billion Euros, Bosnia and Herzegovina with 12.7 billion Euros (2008), thereby Montenegro with 3.3 billion Euros and Kosovo under UNSCR with 3.4 billion Euros are the weakest, according to 2008 data (the data from WIIW and Eurostat) while Albania and Macedonia are between two ends. If we analyze GDP per capita, Croatia is again at the first place with 10,678 Euros, and this country stands out and takes the lead among other countries of the group, with the GDP per capita going from 1,000 and 2,000 Euros at the beginning of the analyzed period to the year 2000, or 4,000 Euros in 2007 (Figure 2). GDP per capita for Kosovo in 2007 was 1,612 Euros.

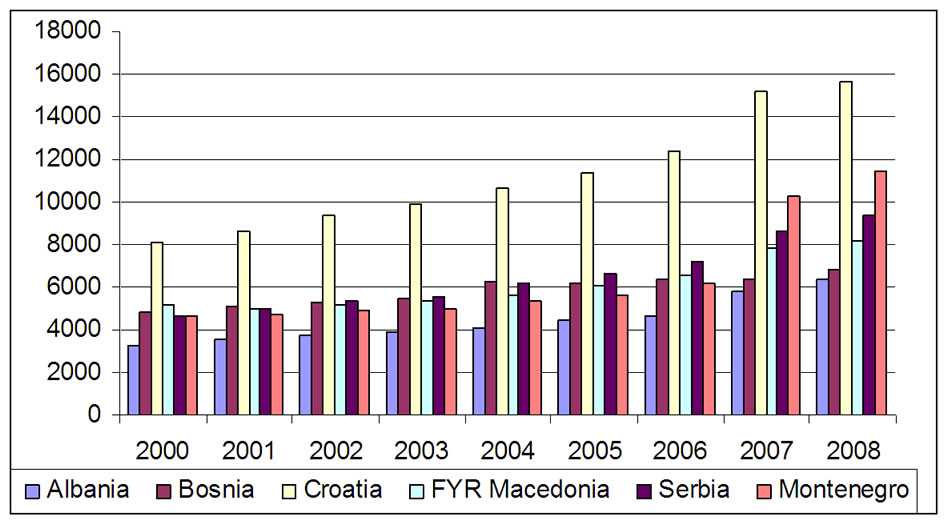

If we look at GDP per capita in Euros at purchasing power parity (PPP), the difference between the most developed country of the region, Croatia, and the rest of the group is less dramatic (Figure 3). Therefore, Croatia distinguishes itself from the group with almost 16,000 Euros at PPP, while the other countries in the group are at 8,000 or 9,000 Euros, except for Montenegro 11,500 Euros per capita in 2008. If we look at the region as a whole, the average GDP per capita would be 9,650 Euros at PPP.

Although relatively high GDP growth rates and achieved high levels can be evaluated as positive and show that implemented reforms were successful, they are not sufficient because of the depth of the transition crisis which struck those countries, so some of the countries still could not reach or significantly surpass the pretransition levels of economic development. Taking into account their economic target, which is EU accession, these countries, except of Croatia, have not achieved a satisfactory results in the area of economy. The GDP per capita in relation to the European average separates Croatia from other countries of the region with GDP per capita reaching 52% of the European average. In 2008, Croatia reached 63% of EU-27 GDP per capita which is three times more than other countries. Namely, in 2006 Albania had the lowest position, with 21% of the European average, Bosnia and Herzegovina had 26% of the European average, FYR Macedonia had 28%, and Serbia and Montenegro had 33% of the European average [9].

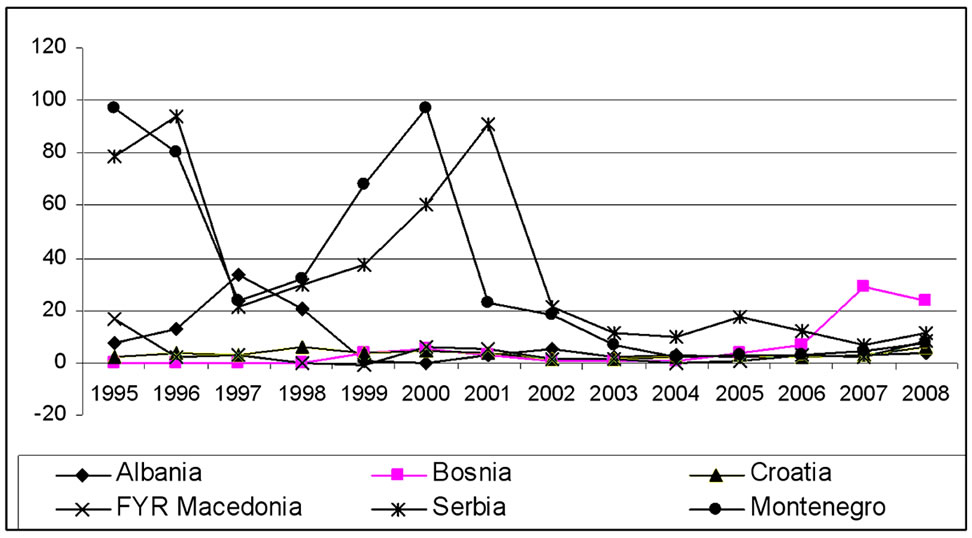

Except for the development cycle which can be, as seen above, evaluated as positive, but with many negative elements, these countries have managed to achieve good results in the area of price stabilization, especially after year 2001 when the region as a whole (Figure 4) solved the problem of inflation.

According to the data in Figure 4, all the countries of the region in the mid 90’s of the last century had successfully solved the problems of inflation, except Serbia and Montenegro, which still had the inflation at the annual rate of 80 to 100% (1995 and 1996). Stabilization measures in these countries decreased the inflation to 20% during 1997, but the inflation erupted again in 2000 (Serbia) and 2001 (Montenegro). After 2002, the inflation problem is gradually resolved in the region, since it

Figure 2. GDP per capita in the Western Balkans in Euro, 2000-2008.

Figure 3. GDP per capita at PPP in the Western Balkans in Euro, 2000-2008.

Figure 4. Inflation rate in the Western Balkans, 1995-2007.

is at 6%, showing the efficiency of the reforms regarding the stabilization of the economy. After 2005 data it is evident that the price rose faster then in the rest of the region.

The area that still has not showed positive results and most certainly needs extra effort that would improve economic and social losses of the society is the labour market. At the beginning of transition, the need to establish a profitable business emphasized the problem of redundant labour, the workers were laid off in the process of restructuring. The situation generated increased pressures at the labour market, and together with the young people searching for a job for the first time, the unemployment rate has increased to above 40% in some countries.

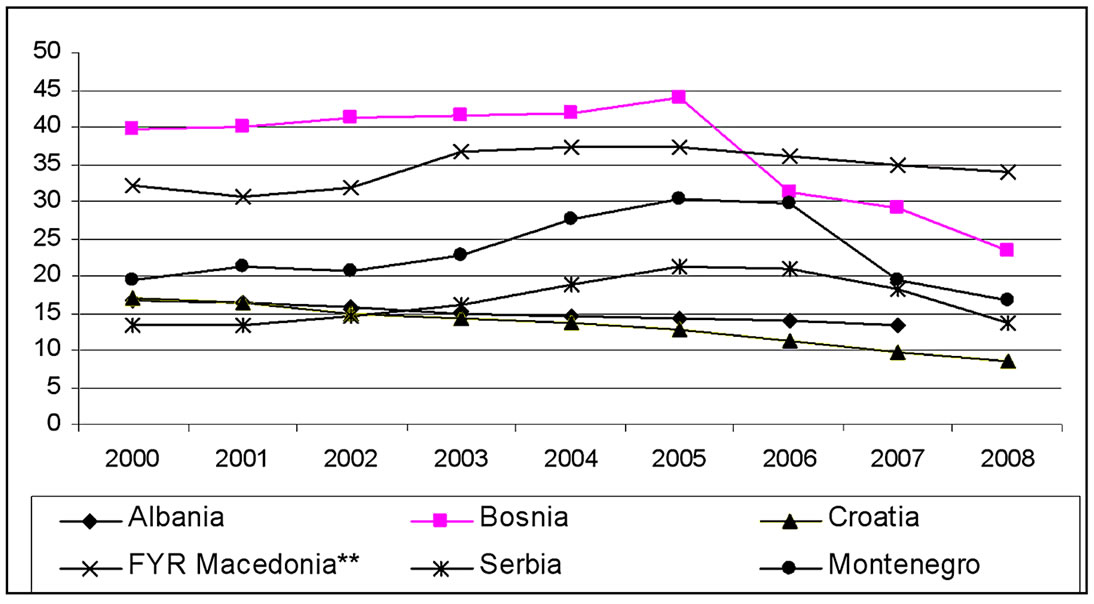

Figure 5 shows that FYR Macedonia has the biggest problem of unemployment, with the rate of 34% in 2008, Bosnia and Herzegovina follows with the rate of 23%. That country successfully coped with the problem of unemployment from 2005 onwards, and since then is continually decreasing the rate. The smallest unemployment rate, continually decreasing, from 16.8% in 2000 to 13.4% in 2007, was recorded in Albania, and Croatia also achieved some positive movements with the rate continually decreasing since 2001, and in the last year of the period analyzed it came down to 8.4%. As a general rule, Western Balkan countries did not manage to start up their economies by opening new production facilities and new workplaces, so the existing structure raised the unemployment problem together with inevitable cyclical and frictional, to a very high, in some countries even alarming levels. It is obvious that in these countries the privatization process and structural reform have not achieved the expected results, so the problems on the labour market still remain strong.

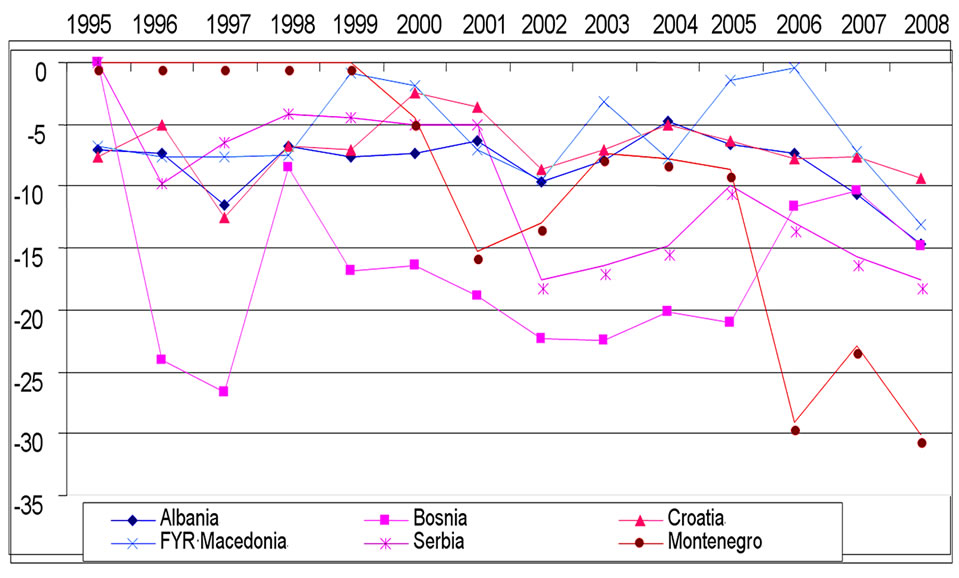

Also, the Western Balkans was not very successful in the area of foreign trade if we assess current account deficit. The initial liberalization of foreign trade, together with the economy that was not strong enough, resulted in rapid growth of imports and further increase in trade deficit and current account balance deficit (Figure 6).

The greatest current account balance deficit in 2008, observed as a share of the GDP, was recorded in Montenegro (30.1%), then in Serbia (17.1%). The share of current account deficit in the GDP of Albania was 14.9%while for Croatia this indicator was at 9.3% in 2008. The other countries were realized deficit of current account more then 10% of their GDP.

Unsatisfactory competitiveness of national companies, the beginning of foreign trade liberalization, population becoming more and more a part of the consumer society, and companies requiring investment all had an influence on high trade deficits and incurring new debts.

According to calculations based on WIIW data, Croats have the largest debt per capita, 6,500 Euros in 2007. This indicator is three times the amount of Serbia, and six times the amount of Montenegro, with the rising trend since 2000. The smallest amount of external debt records Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina and FYR Macedonia. The need to increase external debt was most certainly generated by the development cycle of a country on the one side, but on the other side also by insufficient interest of foreign investors, primarily due to political instability, as defined in the chapters that follow.

On the basis of conducted analysis, it can be concluded that Western Balkan countries achieved satisfactory results in the area of their internal balance, primarily in the domain of price stabilization, while the problems in the external area still remain grave as seen in the equilibrium of balance of payment and foreign debt. The problem of debt would not be so alarming if the countries managed to start the development cycle generated by new production facilities and new jobs openings, which was not the case. Namely, development cycles that were started were based on increased domestic, personal and national consumption for which incurring foreign debt is inevitable, and this cannot be the strategy of long-term sustainable development cycle.

3.3. Evaluation of Transition Processes through Transition Indicators

Based on the above-mentioned EBRD transition indica-

Figure 5. Unemployment rate in the Western Balkans, 2000-2008.

Figure 6. Current account balances in the Western Balkans, 1995-2007 in per cent of GDP.

tors, Western Balkan countries have achieved significant progress in the last couple of years. Croatia achieved the best results in the region in all indicators except in price liberalization, and if countries are analyzed as a whole, best results are with small scale privatization and trade and foreign exchange system. Infrastructure reform, securities market and non bank financial institutions were evaluated as worst, together with competition policy, but in these areas big progress was made in the last couple of years. These countries have a relatively low score in governance and enterprise restructuring. In recent years Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina achieved some progress in increasing private sector share, and Bosnia is still in the domain of large scale privatization. Largest private sector share in GDP is recorded in Albania -75%, followed by Croatia with 70%. On the basis of the presented data we can conclude that Croatia is the most successful country of the region, while all other countries are more or less at the same level of achievement.

4. Is the Interest of Foreign Investors for Croatia Satisfactory?

The prevailing opinion in literature dealing with economy is that the ability of a national economy to attract foreign capital represents a great potential for the growth of developing countries. [10]. Among other things, foreign capital can have the function of increasing national savings, usually savings are at low levels in less developed countries, which enables the countries to increase the investment rate and thereby achieve better development results. In the long run, through acceleration of the development cycle, this increases the growth potential of a country and the standard of living access to international capital market provides the means to finance increased needs for resources in developing countries. It is not only the fresh capital that is relevant, but also more intangible assets. Some types of foreign capital inflows, principally foreign direct investment (FDI), facilitate the transfer of managerial and technological know-how, which is really important for those countries [11].

However, the FDI usually goes to the countries where it is possible to combine the ownership advantages with the location specific advantages of the host countries through internationalization advantages of foreign investments [12]. Western Balkan countries do not have a significant potential for attracting foreign investors. In an economic sense, direct investments depend on different aspects of investments: the motive for investment (market-seeking, resource-seeking and efficiency-seeking), type of investment (greenfield or brownfield), the sector of investment (manufacturing or services) and the size of multinational company or investor. However, one must also include location-specific factors, which are more stable over the period. According to the above mentioned, the principal economic determinants of the FDI in specific case could be different. The market-seeking FDI aims at penetrating the local markets of host countries and is usually connected with: market size and per capita income, market growth, access to regional and global markets, consumer preferences and structure of domestic market. The resource-asset seeking FDI depends on prices of raw materials, lower unit labor cost of unskilled labor force and the pool of skilled labor, physical infrastructure (ports, roads, power, and telecommunication), and the level of technology. The efficiency-seeking FDI is motivated by creating new sources of competitiveness for firms and it goes where the costs of production are lower. In this last case, prior to decision, foreign investors consider price of factors of production (adjusted for productivity differences) and the membership in regional integration agreement [12]. Consequently, the efficiency-seeking FDI covers both previously mentioned types of the FDI. It is necessary to stress that is not possible to distinguish exactly between firm-specific and country-specific determinants of the FDI, or to determine motives of small versus large foreign affiliates.

Global FDI inflows increased in all three groups of economies: developed countries, developing countries and the transition economies of South-East Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) in recent years [13]. China, Hong-Kong and Singapore were most attractive to foreign investors in the previous period, and among transitional economies it was Russian Federation. Considering market size of countries that are most interesting to foreign investors and the price of labour, the position of Western Balkan countries is far worse, but world trends are none the less followed in that segment.

Western Balkan countries became interesting for foreign investors only after 2000, except for Croatia which had significant foreign investment since 1995, immediately after the war ended. This relatively weak and shifted interest of foreign investors in Western Balkan countries, if compared to other transition economies, is explained by political instability of the entire region. But, even though the investments in the whole region increased after 2000, they are still low and unequally distributed. All countries are not equally attractive to the investors, biggest investment is in Croatia, while Serbia became especially attractive after 2004. Raising interests and FDI inflows towards the region in recent years were driven by the privatization of state-owned enterprises and by large projects benefiting from a combination of low production costs in the region and the prospective entry of Bulgaria and Romania into the EU [13] if we analyze South-East Europe.

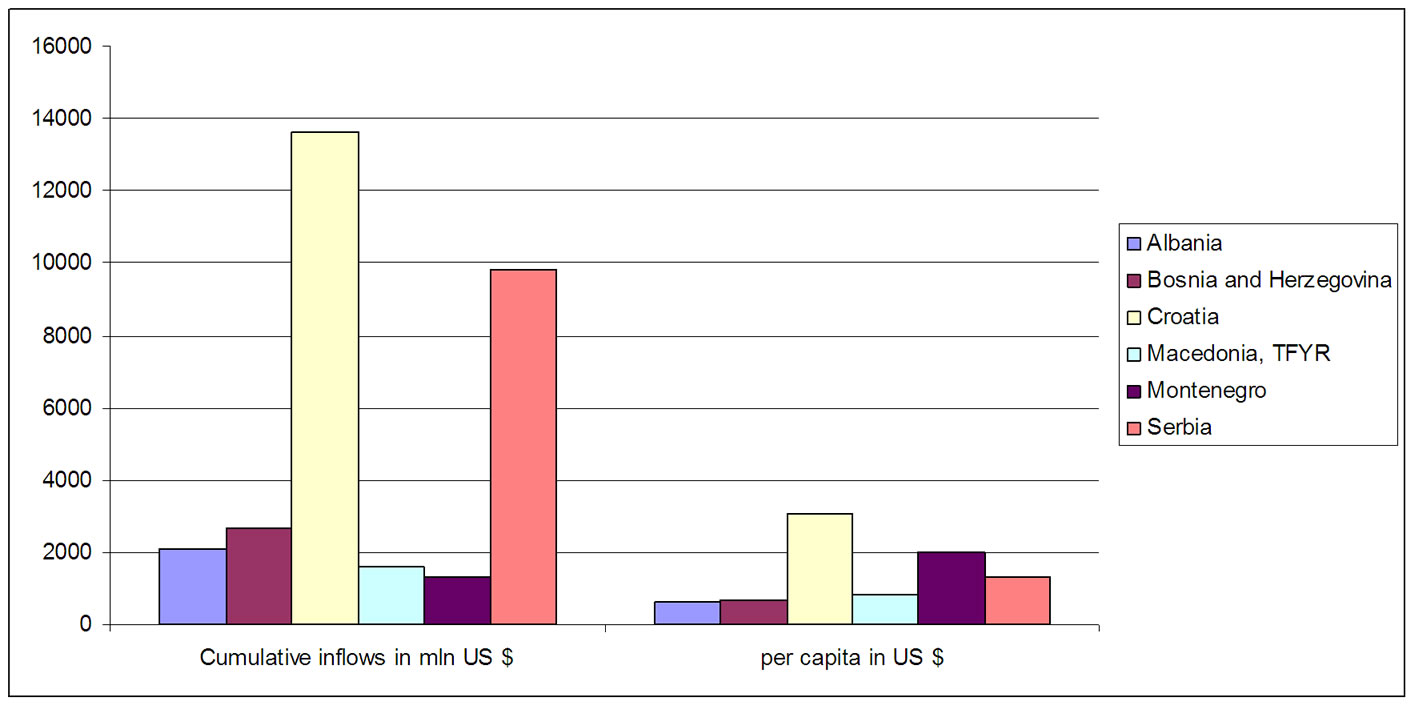

In the period from 1989 to 2006, foreign investors invested around 31.2 billion USD in the entire regionwhich amounted to around 1,450 USD per capita, while ten new members of the European Union accounted for around 4,700 USD per capita. From the investments mentioned, 44% was invested in Croatia, 32% in Serbia, while four other countries had the investment of about 26%. Montenegro was the country with the smallest number of investments, but this is also the smallest state regarding the size, so, as a small market it has poor economic power and thus does not attract investors. The share of FYR Macedonia in total accumulated FDI from 1989-2006 was 5.2%, followed by Albania with 6.7%, and Bosnia and Herzegovina with 8.6% (Figure 7).

If we look at FDI per capita for the period, the situation is a little bit different. Croatia is at first place with 3,067 USD, Montenegro second with 2,009 USD, and Serbia third with 1,312 USD, while other countries of the region are at below 1,000 USD per capita.

Škuflić and Botrić [14] explored determinants of foreign direct investment for the countries of South-East Europe, which, alongside with Western Balkan countries, also includes Bulgaria and Romania. Their analysis shows that market-seeking determinants of the FDI are significant, as well as resource seeking determinants (labor cost). They attribute this finding to the fact that FDI in SEEC is predominately directed towards the service sector and is rarely connected with greenfield investments or generally investment in manufacturing sector. For the latter, the relative labor cost is more important as an attraction factor, than for the service sector. They find that the type of FDI is relevant for determining what set of characteristics of the national economy is important for FDI attraction. FDI in specific industries of the national economy do depend on certain characteristics, which could only be partly explained by the overall economic state in the country.

Figure 7. Foreign direct investment cumulative and per capita for the period 1989-2006 in the Western Balkans.

5. Conclusions Remarks

Today, almost two decades after the transition process started, we can safely say that there are two basic groups of countries; the ones that have overcame the difficulties of transition and became a part of the developed Europe, and the ones that were less successful. The less successful ones include Western Balkan countries, but within this second group there are some differences. The Western Balkans is geographically situated at the margins of the EU, the area became the focus of future integration after the last enlargement of the European Union, but this area also suffered many crisis, political turmoil and disintegration which had a significant influence on slowing down the transition of the region. Successful countries of Central and Eastern Europe, unlike Western European countries, also had different starting points and poor reform background, but their transition, although difficult, reached the pre-transition levels by the end of 1999, and some of them maybe a year later. Western Balkan countries are small countries with the population of around 21.5 million, and with poor economic power. Croatia stands out with the average GDP per capita of about 15,600 Euros at PPP, but still far behind Slovenia (22, 700 Euros), Czech Republic (20,100 Euros), Hungary (15,700 Euros), and even Poland (14,400 Euros). Croatia also achieved better and positive results of the transition process, which are even better that the ones of some countries that joined the EU in the last enlargement.

Analysis shows that the transition process depends on reform background, starting positions, the circumstances in which the transition takes place and the willingness of the nation to face inevitable problems imposed by the elements of market economy. Without any doubt, the transition is much easier if foreign investors are included. They bring not only fresh capital and intensify the investment cycle, but also bring knowledge and new technologies, which all together boost the transition process. Foreign investors are absent in Western Balkan region and the reliance on borrowing capital led those countries in debt problems. Due to insufficient own knowledge mentioned countries are not successfully implemented reforms. Thereby, all of them are not ready to cope with the demanding European market. As analysis showed that it is necessary to evaluate the countries in the process of EU accession separately. It is expected that Croatia will, once entering the EU, accelerate its development cycle and achieve progress in strengthening the basis for production and exports. Other countries, based on the economic indicators achieved so far, can expect to join the EU between 2010 and 2015. Due to significant development gap between Western Balkan countries, it would not be properly to observe the region as a whole and apply a singular strategy of the EU accession because this approach would have a negative impact on Croatia, as the most developed country of the region.

6. References

[1] D. Vojnić, “O nekim koncepcijskim i empirijskim problemima ekonomije i politike tranzicije,” Ekonomski pregled, Informator, Zagreb, Vol. 45, No. 5-6, 1994.

[2] D. Vojnić, “Ekonomija i politika tranzicije,” Ekonomski institut i, Informator, Zagreb, 1993.

[3] O. Havrylyshyn and T. Wolf, “Determinants of Growth in Transition Countries,” Finance & Development Magazine, International Monetary Fund, Vol. 36, No. 2, June 1999.

[4] D. Dubravčić, “Makroekonomska politika i tranzicijska kriza,” Zbornik radova znanstvenog skupa “Susreti na dragom kamenu, Pula, Ekonomski fakultet, Dr. Mijo Mirković, Vol. 18, 1992.

[5] L. Škuflić, “Međunarodne trgovinske strategije zemalja u tranziciji,” Magistarski rad, Rijeka, Ekonomski fakultet Rijeka, 1997.

[6] A. Schipke and M. A. Taylor, “Theory and Practice in the New Market Economies,” The Economics of Transformation, Springer-Verlag, Berlin, 1994.

[7] V. Tanzi, “Transition and the Changing Role of Government,” Finance & Development Magazine, IMF, Vol. 36, No. 2, June 1999.

[8] L. Škuflić, V. Botrić and J. Ladavac, “Problemi, ostvarenje i perspektive tranzicijskih procesa u zemljama srednje i istočne europe, Hrvatsko gospodarstvo u tranziciji,” Zbornik radova EIZ, Zagreb, 1999.

[9] EUROSTAT, New release, No. 179, 17 December 2007.

[10] B. Bosworth and S. M. Collins, “Capital Flows to Developing Economies: Implications for Saving and Investment,” Brookings Paper on Economic Activity, Vol. 30, No. 1, 1999.

[11] L. Škuflić and V. Botrić, “Main determinants of Foreign Direct Investment in the South East European Countries,” Transition Studies Review, Springer, Vol. 13, No. 2, 2006, pp. 359-377.

[12] United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, “Investment and Innovation Policy Review: A Conceptual Framework,” World Investment Report, New York, 1998.

[13] United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, World Investment Report, New York, 2007.

[14] L. Škuflić and V. Botrić, “Foreign Direct Investment in the South East European Countries: The Role of Service Sector,” Eastern European Economics, M.E. Sharpe, Inc. Vol. 44, No. 5, September-October 2006.