iBusiness

Vol.1 No.2(2009), Article ID:1043,8 pages DOI:10.4236/ib.2009.12009

On Entrepreneurship, Intentionality and Economic Policymaking

![]()

1,2Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Madrid, Spain; 3Universidad Rey Juan Carlos, Madrid, Spain; 1,2,3Instituto de Investigaciones Económicas y Sociales (IIES) “Francisco de Vitoria”, Madrid, Spain.

Email: felix.munoz@uam.es

Received September 10, 2009; revised October 16, 2009; accepted November 23, 2009.

Keywords: Entrepreneurship, Intentionality, Evolutionary Economic Policymaking

ABSTRACT

Within evolutionary economics, entrepreneurship is seen as the main force of economic change, as the agency of self-transformation within restless capitalist economic systems. Therefore, a truly evolutionary perspective on economic policy-making must consider the significance and scope of entrepreneurship. On the basis of such a perspective, it might be possible to assess future outcomes of economic evolution under different policy measures related with, for instance, stimulating entrepreneurship as a policy that would provide the seeds for recovery from a slump in an economy. In this short note, our main claim is that the very nature of entrepreneurship implies the recognition of the role played by entrepreneurs’ intentions, their tendency towards transforming goals and agents’ spaces of action. Recognition is possible due to a more systematic analytical integration of these elements into a theory of entrepreneurship based on a ‘production of action’ conception (vs. the standard framework based on a ‘technology of choice’). This analytical vision sheds light on how economic policymaking should be implemented to stimulate entrepreneurship.

1. Introduction

Any theory of economic policymaking in an evolutionary perspective should examine the significance and scope of entrepreneurship. This interest is partially compatible with developing a solid theoretical base for an evolutionary theory of economic policymaking [1]. There are also ‘practical’ reasons: in periods of economic slump, politicians look for economic policies and instruments that pull the economy out of recession. In their efforts to do so, they usually claim that crises open up new periods of economic opportunities. Some of them even point to entrepreneurship and policies that stimulate entrepreneurship as one of the forces for providing the seeds for recovery.

In any case, many important questions arise. For instance, what is the role of entrepreneurship in relation to the emergence of new opportunities? What do such opportunities involve? How does ‘entrepreneurship’ explain ‘economic change’? If we take for granted that entrepreneurship plays a substantive role in the explanation of structural change, what implications would it hold for economic policymaking? Might there be a trade-off between the forces that are promoted by entrepreneurs and stimulated by politicians?

In order to deal with questions like these, an approach that integrates ‘entrepreneurship’ and ‘economic policymaking’ is needed. In this paper, we present an approach that may identify certain fundamental common elements at the base of the links between entrepreneurship, the generation of novelties, socio-economic self-transformation processes and economic policymaking. This approach, the so-called action plan approach [2], pre-requires a theoretical treatment of intended action.

The main thesis we propose here is that the categories of intentionality–such as belief, goal, intention, collective intentionality, etc. [3,4]–are necessary for a substantive explanation of entrepreneurship. The argument is consistent with the role these categories of intentionality play in cognitive sciences, artificial intelligence and social philosophy, etc. and in the explanation of individual and collective behaviour and the emergence of institutions [5–7]. Moreover, the goals and intentionality of agents play an essential role in the explanation of the emergence of novelties and evolving capabilities, institutions and learning processes. Insofar as entrepreneurial and political actions are special instances of human action, the categories of intentionality apply for substantive explanations of such entrepreneurship and policymaking.

What are the implications of the above ideas for economic policymaking? The application of categories of intentionality for the explanation of entrepreneurship and its consequences for economic policymaking do not imply a new catalogue of political economy or new specific means for political action. The main implication is that we need a redefinition of the general context in which economic policymaking is implemented. The action plan approach provides such a general context and basically consists of moving from of a conception of economics as a technology of choice to economics as a conception of production of action. Our claim here is that the latter conception becomes a condition of possibility for implementing a substantive approach to entrepreneurship and to policymaking: a theory of entrepreneurship developed on a ‘production of action’ basis should consider the fact that new goals of action may emerge, the hierarchical ordering of goals may change, goals that have (or have not) been reached may (or may not) be removed from or replaced in agents’ plans, etc. as a result of entrepreneurial experimentation. Moreover, we pose that agents’ rationality depends on the goals and motivations they pursue and this claim is valid for politicians and entrepreneurs alike. Thus, what directs (entrepreneurial, political, etc.) human activity is not only economic calculus, but also the possibility of developing a true open rationality: the rationality of the unexpected in a context of radical uncertainty [8,9]. Economics as a conception of production of action is the compatible analytical context for this ‘true open rationality’.

The paper is organised as follows; Section 2 points out the relationship between entrepreneurship and economic change, where the nexus between the two is novelty; Section 3 discusses the implications of the treatment of entrepreneurship from a ‘production of action’ point of view; in this context, Section 4 considers entrepreneurship and economic policymaking; the paper ends with concluding remarks.

2. Entrepreneurship and Economic Change

Significant contributions that address entrepreneurship lead to the identification of a common key element which lies at the basis of the links between entrepreneurship, self-transformation and the endogenous generation of novelties. This key element is that entrepreneurs do plans which involve transforming goals, and attempt to execute them interactively within the economic system. In doing so, they transform the socio-economic system.

How do they accomplish this function? Basically, entrepreneurs transform agents’ spaces of action within an economic system. Entrepreneurs do this through a continued action linked to what we designate as entrepreneurs’ goal dynamics: it is the entrepreneurs’ intention to transform the human and physical environment that surrounds them according to the goals (objectives) they have set, and which they have previously imagined and valued more than other alternatives. Together with the associated intentions and the means/actions the agents consider necessary for their fulfilment, these goals configure their action plans and once they are being deployed in interaction with the plans (and actions) of the other agents in the economy, they produce their effects in and transform the reality. Thus, intentionality and goals take on a central role in the explanation of the economic change.

2.1 Intentionality and Novelty

Although the importance of intentional action has been recognised in the evolutionary literature [19,20], evolutionary economics generally proceeds in its models and theories as if the goals pursued by agents were given. The evolutionary tradition has focused mainly on the role of knowledge to explain entrepreneurial behaviour. For some economists the distinctive function of entrepreneurs consists of generating [21], organising [22], and using [23] knowledge. Other contributions also give an important role to entrepreneurs’ imagination [24] and creativity, etc. Until recently the analysis of the role played by agents’ intentionality and the goals they pursued in the development of new capabilities and new patterns of behaviour, etc. had been postponed [25]. However, a deeper analysis shows that all these approaches to entrepreneurship literature are compatible with the recognition of the role played by entrepreneurs’ intentions, with their focus on transforming goals.

Furthermore, this recognition should turn a more systematic analytical integration of these elements (means, actions, goals, intentions, knowledge, imagination and practical rationality, etc.) into a theory of entrepreneurial action and economic change. An approach that allows for a theoretical treatment of intended action seems to be a pre-requisite for exploring the very nature of entrepreneurship. The underlying idea is that agents’ intentionality is a necessary condition for a substantive explanation of entrepreneurship. This idea is consistent with the role played by the categories of intentionality, such as belief, goal, intention and collective intentionality, etc,, in cognitive sciences, artificial intelligence and social philosophy, etc. to explain individual and collective behaviour and the emergence of institutions [4,5] and socio-economic systems [26,27]. Additionally, goals and intentionality play an essential role in explaining the emergence of novelties and evolving capabilities [28], institutions [29] and learning processes [30].

Thus, entrepreneurship does require a tendency towards a transforming goal. As these goals must be the goals of somebody, this is the reason for the existence of ‘creator personalities’ [31]. The label ‘creator personality’ designates a locus for novelty. Novelty goes together with a transforming intention which results in the breaking of symmetries and the introduction of jumps, which becomes visible through the existence of constructive impulses, through the ability of being necessarily alert to discover and being necessarily ready to act on the basis of thoughts not held by others, etc. From this point of view, entrepreneurship can be considered as a transforming impulse and the will that points action towards the generation of change. These transforming impulses and the collective interactions (both on and off markets) generate the variety that fuels the evolutionary processes of diffusion, selection and retention. Schumpeter’s [31] example of Mantegna’s innovations could be interpreted as a conscious and individual act undertaken by the painter; but it could also be shown as a precursor of the ‘Renaissance style’.

2.2 Entrepreneurship, Action Plans and Novelty

Economic self-transformation processes involve learning processes, as well as the emergence of completely new actions that cannot be explained only by means of mere knowledge acquisition [32]. In this context, an ‘action plan’ is the projective ordering of means to achieve goals located in the imagined future. The very nature of action plans is the projective character of the ordering that is involved. The action plans individuals elaborate are idiosyncratic. They can also be plans that coordinate the action and goals of many people: a plan for a trip, a company’s business plan, a plan by the European Commission to achieve the objectives of the Treaty of Lisbon. An action plan can include routine patterns of behaviour, strategic designs and monitoring and valuation procedures.

A plan can also refer to its goals at several points in the future, represent hierarchical dependencies among goals and actions with as many analytical moments in time as may be required, as well as alignments of goals with other individuals’ plans. Its projective character refers not only to the fact that historic time (and timing) play central roles in explaining human action, but also that actions and goals need to be imagined before they are deployed by agents1.

Agents choose their goals of action on the basis of psychological, social, and cultural factors, as well as ethics and beliefs [33], etc. Agents constitute their action plans using their imagination [34], taking into account that the goals they pursue are located in an imagined future [35]. Accordingly, it could be said that agents ‘invent’ the future on which they focus their actions. This idea is valid whether we consider objectives in the short, mid or long term. The opportunities for acting in a specific way (entrepreneurial action, policymaking, etc.) are not hidden somewhere in the external reality, waiting to be discovered by entrepreneurs or policymakers, but they ‘emerge’ initially in agents’ minds regardless of the fact that at some time in the future they may be embodied in a written document or an organizational form, etc. Action plans are an open analytical representation of agents’ projective action, in which means and goals are not given but rather produced by the agents themselves. At each moment in time, an action plan may be interpreted as a template or ‘guide’ for action that projectively connects elements of a different nature: something the agent wants to achieve (goals) with the actions and means the agent ‘knows’ afford him/her success2.

Searching for novelty in economics sometimes corresponds to the perception of opportunities to get better results than those achieved through actions deployed in the past and present [37]. If this were the case, how would the action plan framework contribute to the study of entrepreneurship? The answer is that the action plan approach makes it possible to point out where novelties can be located.

Novelties operate in economic systems because economic agents (individuals and organisations) incorporate them into their spaces of representation when they configure their action plans and, in particular, when they settle their goals, thereby producing choice ex novo3. ‘Rational choice is an inadequate explanation for behaviour, because neither the empirical premises nor the objectives of behaviour can be logically derived’ [38]. As Loasby points out, following Hume’s dictum, the search for novelty cannot be rational: ‘no kind of reasoning can give rise to a new idea’. Creating opportunities for choice is, in the first place, producing new objectives of action. When agents incorporate new goals and intentions into their plans, they trigger the process of discovering new means to achieve these goals. If we consider novelty in goals as the most general case, we can treat other particular cases as novelties in means, given objectives and given means, etc.

Agents’ action plans require the definitive abandonment of the timeless framework of the ‘technology of choice’. The paradox of a timeless approach as an analytical basis for the explanation of processes that are necessarily deployed in time is solved through the dynamic openness of the actions and goals pursued by agents. The classical definition of economics offered by Robbins is essentially correct, but it is not sufficient.

3. Entrepreneurship from a Conception of ‘Production of Action’

As already pointed out, entrepreneurship consists of setting a new goal the agent desires, triggering the production of action the agent deems necessary to achieve the goal, and thus, if successful, giving rise to unheard-of possibilities for the agent. From the viewpoint of a theory of entrepreneurship, it is not enough to consider the possibility of agents (entrepreneurs) learning new ways for achieving given ends. The true challenge for a theory of entrepreneurship consists of agents’ admission of the endogenous generation of new goals, which finally give rise to new spaces of action for the agents themselves.

3.1 Explaining Entrepreneurs’ ‘Production of Action’: Novelty and Economic Change

Moving from a conception of economics as ‘technology of choice’ to a conception of economics as ‘production of action’ reveals the decisive role of entrepreneurship, novelty and agents’ intentionality in the explanation of economic change. The entrepreneur’s most important role is the production of new courses of action; in other words, producing new economic situations. This is the very nature of entrepreneurship in the context of ‘production of action’: entrepreneurship requires a focus on a transforming goal. This focus involves learning processes but it can also imply the emergence of completely new actions that are not explained solely by mere knowledge acquisition processes4.

The entrepreneur—the ‘creator personality’, the locus of novelty—is both a ‘maximizer’ and a ‘rational’ agent. However, contrary to the neoclassical entrepreneur, in our approach the entrepreneur sets out the formal achievement of goals, which may be completely new goals that are hierarchically superior to all the other goals, etc., and for these reasons goals act as the norm of their own action plans. The entrepreneur defines his action plans with the setting of a goal he/she desires: the entrepreneur wants to produce that goal. From the ‘production of action’ point of view, we can also pose that the entrepreneur is rational: human action, qua rational, within human constraints, is intended action; there must be goals (reasons) for acting [40]. Like the other agents in the economy, entrepreneurs decide what their goals of action are (and what they are not) and which place they should be given in their action plans. These decisions are regardless of what their goals or actions are with or without a price.5 The conception of production of action is analytically compatible with this true open rationality, where entrepreneurship plays a substantive role in the explanation of structural change. The projective links between entrepreneurs’ goals and actions and their interactive deployment imply the endogenous generation of novelties and self-transformation.

However, the identification of novelty is of little interest in itself if the consequences in terms of economic change are not explored. Let us briefly consider the logical links for the following thesis: entrepreneurship is a source of economic change. If economic change is ‘dynamic endogenous structural change capable of inducing or generating novelties’; if structural change refers to processes that transform these structural elements; if novelty refers to the occurrence of something that has not previously taken place within any of these elements; and if novelty could be produced by entrepreneurs as a result of their goals, dynamics and transforming intentions; then entrepreneurship generates economic change. The very entrepreneurial function consists of changing the agents’ spaces of action through a transforming impulse (linked to novelty) that points action towards the generation of change. As already suggested, transforming impulses in the entrepreneurs’ action plans generate the variety (and collective interactions on and off markets) that fuels evolutionary processes.

Assuming that entrepreneurship plays a substantive role in the explanation of structural change, could we point to the implications for economic policymaking from an evolutionary perspective?

4. Entrepreneurship and Economic Policymaking

Witt [1] claims the need for the rigorous incorporation of the common assumptions of evolutionary economics on agents’ behaviour and other framing conditions into normative analysis6 As Witt points out, some of the characteristics inherent to the processes of public choice and public intervention, which should be part of the normative analysis [41] of the processes of economic changes, are bounded rationality, the endogenous generation of new factual and normative knowledge and social interaction in competitive social environments. The political economy of actual policymaking, the analysis of policy instruments (for given ends), and the debate on policy goals and their legitimization (Witt [1]; italics added) must account for the possibility of changing knowledge constraints. However, what can be said about transforming changing goals (the key element of entrepreneurship) in relation to economic policymaking?

4.1 Considering the Requirements for Evolving Policymaking

The main challenge for policymaking is how to deal with the agents’ ‘production of action’ in the (socio-) economic system. For instance, adaptive policymaking processes should imply promoting learning and taking care of flexible market performance; policymaking should also promote the search for novel action (Witt [1]: 80). Decision-making, the fundamental pillar of policymaking, which includes the exchange of information, the revision of data and the evaluation of the different alternatives (policy goals), etc., in short, the role of the policy-maker, is considered within the limits of public choice theory or, more generally, political economy as the result of the behaviour of a ‘maximizer’, an agent that does not stop until he/she finds the best option or as the result of a ‘satisfier’ [42] in the case of an agent that behaves with limited information and bounded rationality.

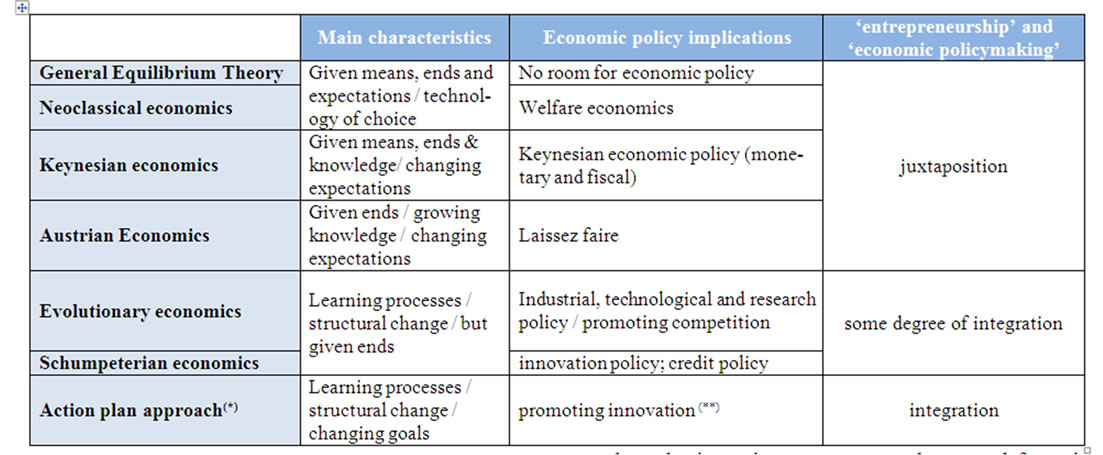

However, in the context of political economy as it is usually presented in textbooks and mainstream economics, both separate interests and defects in voting rules, institutions and markets, etc. are seen as ‘policy failures’. Thus, it could be considered that in the context of orthodox political economy the relationship between economic and political processes (and therefore, between economics and policymaking) is one of mere juxtaposition (Figure 1). Economics and policies are set side by side in such a way that the anomalies conventional economics (from a conception of ‘technology of choice’) reveals certify the presence of failures within the processes of valuation and choice by agents. Conventional economic theorizing does not provide a sufficiently analytical base for integrating behaviours based, for instance, on non-consequentialist motivations, changing preferences or, more generally, (endogenous) changing goals7.

Reducing the gap between evolutionary economic theorising and policymaking, or rather, integrating theorizing and policymaking would require theory to consider the very fact that new goals may arise, the hierarchical ordering of goals may change, goals that have been achieved may be removed from action plans and goals that have not been achieved may be replaced with other goals, etc.

With regard to the purpose of this paper, our claim at this point is that one necessary condition for developing a consistent theoretical base for an evolutionary or Schumpeterian theory of economic policymaking is that evolving policymaking can only be approached from a systemic analysis in which the economic action of the agents involved in the system is essentially a projective action [2]. It is in this kind of system where, as already mentioned, entrepreneurship, intentionality and novelty are central elements for the analysis. Indeed, this kind of system requires adaptive policymaking [43], given the impossibility of setting fully rational8 socio-economic policy designs and policy experimentation and variety, which are essential for individual and social adaptability.

These requirements are better recognized in dynamic spaces of action without a preset time horizon and where the genuine multidimensionality of decision-making (by policymakers) means that that agents may continuously deploy learning and experimentation processes. This is possible if we analytically open the means/actions and the goals of action. This is the only logical approach compatible with a vision of policymaking in a truly evolving economy, in which time has real meaning. We refer to economics as a theory of the ‘production of (human) action’.

4.2 Entrepreneurship as a Challenge for Evolving Economic Policymaking

If novelty can be produced by entrepreneurs as a result of their goals, dynamics and transforming intentions9, then entrepreneurship causes economic change and poses new challenges for policymaking. ‘Evolving economy’ and ‘economic policymaking’ are not juxtaposed concepts; there is a comprehensive relationship between the two. This relationship arises from an approach to economic theory in which policymaking depends, among other causes, on the formulation of new goals by entrepreneurs and policy–makers alike. This analytical approach would make it possible to redefine economic policymaking in order to stimulate (and, to some extent, help organize)

Figure 1. Juxtaposition vs. integration of ‘economic’ and ‘political’ processes.

Table 1. Modes of theorizing and policy implications, (*) As special cases, the action plan approach integrates the above types of theorizing, (**) More research is needed

entrepreneurship by, for example, fostering the creativity of individuals. However, the fact that the specific content of goals, which depend on the individuals’ beliefs, knowledge, experience and intentionality, etc., may produce their effects through the actions of the individuals themselves also implies the recognition of and challenge for policymaking. Agents can devise, create and imagine, etc. new courses of action by forming new spaces of action.

It is in this conception of spaces of action permanently renewed by the entrepreneur’s action and the transforming goals he/she wants to achieve, where the new challenges for policymaking are to be found: how to manage processes that promote and channel transforming goals. The policymaker’s role should be reconsidered within a context in which the agents’ rationality depends on the goals and intentions they pursue and in which it is necessary to channel the innovative goals as a key element for continuous economic change.

From this perspective it would even be possible to state an evolutionary efficiency criterion within an economic system when agents’ intentionality is being actualised (materialised) through agents’ actions: because of the efficiency of the connections between means/actions and goals, intentions turn out to be actual facts in which goals are being produced. Otherwise, some agents (or all agents) may perceive the fact that they are not achieving their goals, fulfilling their expectations or actualizing (materialising) their intentions as a signal of a certain incompatibility with the actions (i.e. means deployed and timing, but also incompatibilities of goals) carried out and that would merit a (more or less detailed) revision. Thus, bagents may interpret that their action is rationed and, therefore, the performance of the system is below expectations from their own point of view. This kind of judgment applies to policy-makers and entrepreneurs in an economic system. Moreover, an improvement of the performance of the economic processes would require the realignment of agents’ goals or, in the terms used in this paper, the revision of the individual intentionality of the agents involved in the system.

5. Concluding Remarks

The mere existence of entrepreneurial forces operating in the economic system is a fundamental and permanent challenge for economic policymaking. It is impossible to conceive any economic system without entrepreneurial action. A first implication of this approach for policymakers is that it is necessary to abandon all mechanicistic approaches to economic policymaking if we want policies that stimulate entrepreneurship, allow the generation of variety and selection (through competitiveness) and retain superior forms of organisation and technology [44]. Necessary conditions include an environment that stimulates creativity, imagination and market experimentation (under a system of true competition), etc. and, of course, a non-confiscatory fiscal policy that does not discourage entrepreneurial efforts and healthy credit and monetary policies that allow economic calculus [10,40] and, therefore, the deployment of entrepreneurial action are. However, these conditions are necessary but not sufficient.

The paradoxes of timeless perspectives (as an analytical basis for the explanation of policymaking applied to processes that necessarily unfold in the time) are resolved by the dynamic opening of the actions and goals pursued by agents in the context of a conception of the economy as ‘production of action’. Here, the concepts of (economic and political, etc.) intentionality play a key role.

Of course our contribution does not cover the entirety of such vast issues. The aim of this paper is simply to locate the point of connection between economic policymaking and entrepreneurship (a favourite concept of Schumpeter) and this is possible under the common focus of a general theory of human action, where, as Mises stressed, economics is the most developed branch. The theoretical and practical implications of such a theory are almost evident. Thus, we feel that our approach to entrepreneurship and its implications for economic policymaking deserve a place in the research agenda of the twenty-first century.

REFERENCES

- Witt, U., “Economic policy making in evolutionary perspective,” Journal of Evolutionary Economics, Vol. 13, No. 2, pp. 77–94, 2003.

- Rubio de Urquía, R., “La naturaleza y estructura fundamental de la teoría económica y las relaciones entre enunciados teórico-económicos y enunciados antropológicos,” In Rubio de Urquía, R., Ureña, E. M. and Muñoz, F. F., Eds., “Estudios de Teoría Económica y Antropología,” AEDOS-Unión Editorial-IIES Francisco de Vitoria, Madrid, 2005.

- Searle, J. R., “The construction of social reality,” The Free Press, New York, 1995.

- Searle, J. R., “Rationality in action,” The MIT Press, Cambridge MA, 2001.

- Grosz, B. J. and Hunsberger, L., “The dynamics of intention in collaborative activity,” Cognitive Systems Research, Vol. 7, pp. 259–272, 2006.

- Metzinger, T. and Gallese, V., “The emergence of a shared action ontology: Building blocks for a theory,” Consciousness and Cognition, Vol. 12, pp. 549–571, 2003.

- Baldwin, D. A. and Baird, J. A., “Discerning intentions in dynamic human action,” Trends in Cognitive Sciences, Vol. 5, No. 4, pp. 171–178, 2001.

- Knight, F., “Risk, uncertainty and profit,” Houghton Mifflin, Boston, 1921.

- Shackle, G. L. S., “Epistemics and economics,” Cambridge UP, Cambridge, UK, 1972.

- Schumpeter, J. A., “The theory of economic development,” Transaction Publishers, Harvard, 1934.

- Kirzner, I. M., “The meaning of the market process,” Routledge, New York, 1992.

- Penrose, E., “The theory of the growth of the firm,” Basil Blackwell, Oxford, 1959.

- Baumol, W., “Entrepreneurship: Productive, unproductive, and destructive,” Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 98, No. 5, pp. 893–921, 1990.

- Baumol, W., “The free-market innovation machine,” Princeton UP, 2001.

- Dopfer, K., “The evolutionary foundations of economics,” Cambridge UP, Cambridge, 2005.

- M. Casson, “The Entrepreneur,” Totowa: NJ, Barnes and Noble Books, 1982.

- Casson, M., et al., “The oxford handbook of entrepreneurship,” Oxford UP, NewYork, 2006.

- Ripsas, S., “Towards an interdisciplinary theory of entrepreneurship,” Small Business Economics, Vol. 10, pp. 103–115, 1998.

- Nelson, R. R., “Bounded rationality, cognitive maps, and trial and error learning,” Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, No. 67, pp. 78–89, 2008.

- North, D. C., “Understanding the process of economic change,” Princeton UP, Princeton, 2005.

- Harper, D. A., “Entrepreneurship and the market process,” Routledge, London, 1996.

- Loasby, B. J., “Knowledge, institutions and evolution in economics,” Routledge, London, 1999.

- Hayek, F. A., “The use of knowledge in society,” American Economic Review, Vol. 35, pp. 519–530, September 1945.

- Loasby, B. J., “The imagined, deemed possible,” In Helmstädter, E. and Perlman, M., Eds., “Behavioral norms, technological progress and economic dynamics,” University of Michigan Press, Michigan, 1996.

- Cañibano, C., Encinar, M. I., and Muñoz, F. F., “Evolving capabilities and innovative intentionality: Some reflections on the role of intention within innovation processes,” Innovation: Management, Policy and Practice, Vol. 8, No. 4–5, pp. 310–321, 2006.

- Muñoz, F. F., Encinar, M. I., and Cañibano, C., “Is economic evolution blind? The role and dynamics of intended action in economic processes,” International Schumpeter Conference, Rio de Janeiro, 2008.

- Rubio de Urquía, R., “Estructura fundamental de la explicación de procesos de ‘autoorganización’ mediante modelos teórico-económicos,” In R. Rubio de Urquía, F. J. Vázquez and F. F. Muñoz, Eds., “Procesos de autoorganización,” IIES Francisco de Vitoria-Unión Editorial, Madrid, 2003.

- Langlois, R. N., “The dynamics of industrial capitalism. schumpeter, chandler, and the new economy,” Routledge, London, 2006.

- Nelson, R. R., “What enables rapid economic progress: What are the needed institutions?” Research Policy, Vol. 37, No. 1, pp. 1–11, 2008.

- Dosi, G., Nelson, R. R., and Winter, S. G., Eds., “The nature and dynamics of organizational capabilities,” Oxford UP, Oxford, 2000.

- Schumpeter, J. A., “Development,” Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. 43, pp. 108–120, 2005.

- Encinar, M. I. and Muñoz, F. F., “On novelty and economics: Schumpeter’s paradox,” Journal of Evolutionary Economics, Vol. 16, No. 3, pp. 255–277, 2006.

- Metcalfe, J. S. and Foster, J., “Evolution and economic complexity,” Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, 2004.

- Loasby, B. J., “Imagination and order,” DRUID Summer Conference, 2007, www.druid.dk.

- Lachmann, L., “Vicissitudes of subjectivism and the dilemma of the theory of choice,” In D. Lavoie, Ed., “Expectations and the meaning of institutions, Essays in economics by Ludwig Lachmann,” Routledge, London and New York, pp. 218–228, 1994.

- Potts, J., “The new evolutionary microeconomics, complexity, competence and adaptive behaviour,” Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, 2000.

- Shane, S. and Venkataraman, S., “The promise of entrepreneurship as a field of research,” The Academy of Management Review, Vol. 25, No. 1, pp. 217–226, 2000.

- Loasby, B. J., “The evolution of knowledge: Beyond the biological model,” Research Policy, Vol. 31, No. 8–9, pp. 1227–1239, 2002.

- Yunus, M., “Vers un monde sans pauvreté,” Jean-Claude Lattès, Paris, 1997.

- Mises, L., “Human action: A treatise on economics,” Yale UP, New Haven, 1949.

- Pelikan, P., “Why economic policies need comprehensive evolutionary analysis,” In P. Pelikan and G. Wegner, Eds., “The evolutionary analysis of economic policy,” Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, 2003.

- Simon, H., “Reason in human affairs,” Stanford University Press, Stanford, 1983.

- Hodgson, G. M., “Economics & Utopia,” Routledge, London, 1999.

- Metcalfe, J. S., “The entrepreneur and the style of modern economics,” Journal of Evolutionary Economics, Vol. 14.

NOTES

1Imagination plays a central role in this approach since the projective character of action plans implies imagining a future course of action in order to reach one or more goals.

2Accordingly, an action plan may be interpreted as a very special (or rather, complex) system [36]; the elements connected in the system are of two different kinds; on the one hand, we have the action/means and, on the other, the goals. Actions/means are always linked to a goal, whereas goals may also be connected to each other. The goals within this system introduce the direction of an action, a direction that leads into the (imagined) future.

3Thus, action plans are the carriers of novelties.

4Take for instance the interesting case of Grameen Bank: it has reversed conventional banking practice by removing the need for collateral and it has created a banking system based on mutual trust, accountability, participation and creativity. Yunus, the founder of Grameen Bank considered that financial resources ought to be made available to the poor under terms and conditions that are both appropriate and reasonable. Those ideas were at the origins of the microcredit system and they modify the contents and forms of the spaces of agents’ action and, consequently, generate new realities. [39]

5An entrepreneur that maximizes his/her profits and a ‘socially responsible’ entrepreneur (like Grameen Bank) would differ in the specific prescriptive content of the hierarchically superior goals in their respective action plans: for the former, the maximum difference between his/her revenues and their costs; for the latter, a ‘socially responsible’ aim.

6Otherwise, economic policymaking would always be an appendix or a strange element to economic analysis.

7In this context, it is legitimate to question the mere existence of a concept such as ‘political economy’.

8‘Fully rational’ in the sense commonly used of the term ‘rational’ in standard economics.

9Together with learning and creativity, etc. It is very important take into account that not all novelty is a result of intended actions or of the action plans themselves, but the result of the interaction of intended action. Thus, novelty may emerge as an unexpected consequence of interaction.