Psychology 2012. Vol.3, No.6, 494-499 Published Online June 2012 in SciRes (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/psych) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/psych.2012.36070 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 494 Relationships between Stages and Processes of Change for Effective Stress Management in Japanese College Students* Satoshi Horiuchi1, Akira Tsuda2, Janice M. Prochaska3, Hisanori Kobayashi4, Kengo Mihara5 1Cancer Prevention Research Center, University of Rhode Island, Kingston, USA 2Department of Psychology, Kurume University, Kurume, Japan 3Pro-Change Behavior Systems, Inc., Kingston, USA 4Department of Psychology, University of Rhode Island, Kingston, USA 5Cognitive and Molecular Research Institute of Brain Diseases, Kurume University, Kurume, Japan Email: satosato.007@nifty.com Received March 5th, 2012; revised April 3rd, 2012; accepted May 4th, 2012 With a primary prevention focus, it would be important to help populations engage in stress management. The Transtheoretical Model of Behavior Change is one of potentially useful models to formulate inter- ventions. The model describes behavior change as progression through five stages: precontemplation (not ready), contemplation (getting ready), preparation (ready), action, and maintenance. Processes of change (strategies and techniques to enhance the progression) facilitate stage transition. Their use is hypothesized to depend on stage of change. The processes tend to be used the least at the precontemplation stage. Use of experiential processes (affective and/or cognitive strategies such as seeking information) increase over time and tend to peak at the contemplation or preparation stage and then decease. In contrast, behavioral processes (behavioral strategies such as seeking social support) tend to be used most at the action and/or maintenance stage. This study examined relationships between stages and processes of change for effec- tive stress management. Effective stress management is defined as any form of healthy activity such as exercising, meditating, relaxing, and seeking social support, which is practiced for at least 20 minutes. Four hundred and five Japanese college students participated in this study. A paper-pencil survey was conducted at colleges in Japan. The process use was least in precontemplation. Experiential processes peaked in preparation. Except for one experiential process, no significant difference was found between preparation and maintenance. Behavioral processes peaked in preparation, action, or maintenance. Most of these inter-stage differences of processes are in line with the prediction from the model. This study represented an initial but important test of validity of applying processes of change to stress management. The results partially supported its application. Keywords: Processes of Change; Stage of Change; Effective Stress Management; Transtheoretical Model Introduction Psychological stress inversely affects both health (Kopp, Skrabski, Székely, Stauder, & Williams, 2007) and productivity (Watts & Robertson, 2011). Relatively high portions of people who are stressed have been reported in countries such as Japan (Japan Health Promotion & Fitness Foundation, 1996), the United States (Anderson et al., 2010), and European countries (European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, 2006). With a primary prevention focus, it would be important to help populations engage in healthy stress management activities such as exercise, talking with others, or regular relaxation to manage stress (Evers, Prochaska, Johnson, Mauriello, Padula, & Prochaska, 2006; Prochaska et al., 2008). For designing such interventions, it is first necessary to find theories of behavior change to understand people’s readiness to initiate and maintain stress management. The Transtheoretical Model (TTM) (Prochaska & DiCle- mente, 1983) is one of the leading theories of behavior change. It has received international attention from health promotion practitioners for modifying health behaviors (Redding et al., 1999). The TTM extracts and integrates elements from major theories of psychotherapies and social-cognitive models (Pro- chaska, DiClemente, & Norcross, 1992). According to the TTM, behavior change is described as progression through five stages: precontemplation (not ready), contemplation (getting ready), preparation (ready), action, and maintenance. Additional con- structs such as processes of change, decisional balance, and self-efficacy are found to facilitate stage transitions. Processes of change refer to the covert and overt activities that individuals are encouraged to perform in order to progress to the next stage. The five experiential processes include con- sciousness-raising (increasing awareness), dramatic relief (re- acting emotionally to warnings about the unhealthy behavior), environmental reevaluation (considering how the practice or lack of healthy behavior affects others), self-reevaluation (rea- lizing that the behavior change can enhance one’s identity), and social liberation (acknowledging how society is changing to encourage the healthy behavior). The five behavioral processes include self-liberation (making a commitment for behavior change), stimulus control (restructuring one’s environment to facilitate the healthy behavior), counter conditioning (substitut- *This work was supported by Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (A) (18203035) and (B) (22330196) to A. T.  S. HORIUCHI ET AL. ing new and positive behavioral choices), helping relationships (listing and utilizing support), and reinforcement management (using positive reinforcement and reward). These ten processes were initially identified in smoking cessation (DiClemente & Prochaska, 1982; Prochaska & DiClemente, 1983), and then were modified and applied to many other behaviors including exercise (Marcus, Rossi, Selby, Niaura, & Abrams, 1992), ma- mmography use (Pruitt, McQueen, Tiro, Rakowski, Diclemente, & Vernon, 2010), medication adherence (Johnson, Driskell, Johnson, Prochaska, Zwick, & Prochaska, 2006), and stress management (Evers, Evans, Fava, & Prochaska, 2000; Evers et al., 2006). The TTM proposes systematic relationships between stages and processes of change (Prochaska et al., 1992). The processes tend to be used the least at the precontemplation stage. Use of experiential processes increases over time and tend to peak at the contemplation or preparation stage, and then deceases in the action and maintenance stages. In contrast, behavioral pro- cesses tend to be used most at the action and/or maintenance stage. TTM-based intervention studies have been successful in guid-ing populations to initiate and maintain stress management (Evers et al., 2006; Prochaska et al., 2008). Despite such TTM potential, there is limited information on inter-stage differences for the use of the ten processes of change with a reasonable sample size. Relationships between stage and processes of change vary across health behaviors to some extent (Rosen, 2000). To validate the application of processes of change to stress management, it is first necessary to examine whether re- lationships between stage and processes of change are consis- tent with the predictions from the TTM (Velicer, Prochaska, Fava, Norman, & Redding, 1998). Only three studies have been reported which have applied the processes of change to stress management (Evers et al., 2000; Padlina, Aubert, Gehring, Martin-Diener, & Somaini, 2001; Riley, Lewis, Lewis, & Fava, 2008). Evers et al. (2000) found that six of the ten processes significantly differed across the stages, but results of post-hoc tests were not reported. Padlina et al. (2001) examined two higher-order processes (experiential and behavioral). Among the three previous studies, only the study of Riley et al. (2008) examined inter-stage differences of all ten processes’ use, but found that no process differed across the stages. Predicted relationships from the TTM were not su- pported. The results of Riley et al. (2008), however, seem to be largely affected by a small sample size (N = 42). Examination of the inter-stage differences of all ten processes with a reason- able sample size will provide an initial but important test to va- lidate the application of processes of change construct to stress management. The purpose of this study is to examine the relationship be- tween stage and processes of change for stress management with Japanese college students. The authors chose these stu- dents as a sample due to the following two reasons: stress ma- nagement represents a high public health priority for students; they are a convenient sample. In this study, effective stress management is defined as any form of healthy activity such as exercising, meditating, relaxing, and seeking social support, which is practiced for at least 20 minutes. Unhealthy activities include those such as using alco- hol and other drugs, overeating, or smoking. This definition is applied from the stage-based manual for adopting stress man- agement (Pro-Change Behavior Systems, Inc., 2003). The mi- nimum length of time (20 minutes) was added since it was as- sumed to be helpful to give people a time frame. One may think that a more clear definition should be applied. The authors be- lieve, nevertheless, that it is suitable to use such a flexible defi- nition when focusing on daily self-care activity from a primary prevention focus, since there is large variation on what kind of activity people engage to manage stress (Horiuchi, Tsuda, Kim, Hong, Park, & Kim, 2010). Furthermore, Horiuchi et al. (2010) reported that college students who are carrying out effective stress management for more than six months are less stressed than those who do not, supporting the validity of this definition. Based on the TTM, it is predicted: 1) Use of the processes is least in the precontemplation stage; 2) Experiential processes are more frequently used at the contemplation or preparation stage compared to the precontemplation stage, and are lower in the action and maintenance stages than in the preparation stage; and (3) Behavioral processes are most frequently used at the action and/or maintenance stages. The least use of the processes in the precontemplation stage is predicted, since those in precontemplation do not have the intention to initiate stress management, and are least motivated to take action. The most frequent use of experiential processes in the contemplation and/or preparation stage is predicted, since individuals in those stages need to increase readiness to act and these processes are useful to increase such motivation. Most frequent use of behavioral processes by individuals in the ac- tion and/or maintain stage is predicted, since they need to use the behavioral processes for maintaining and increasing fre- quency of effective stress management and behavioral proc- esses are effective for doing so. Method Participants Power analysis showed that a sample size of 295 is required to detect η2 = .04 with power .8. This small to medium effect size was expected based on the study of Evers et al. (2000). They reported medium effect sizes for six of the ten processes which were significantly different across the stages, while no significant difference was found for the other processes. Par- ticipants included 405 college students, of which 52.3% were female. They were students who were in classes one of the research team members taught. The mean age was 19.40, with a standard deviation (SD) of 1.56 years. The students majoring in business, nursing or medicine, psychology, and other were 55.8%, 35.6%, 8.1%, and .5%, respectively. Freshmen in- cluded 65.2%, sophomores 15.8%, juniors 13.6%, and seniors 5.4%. Measures For measuring processes of change, Pro-Change’s processes of change measure for effective stress management (Evers et al., 2006) was translated into Japanese using a back translation procedure after receiving permission from the original authors. It includes 30 items and consists of two higher order and 10 factors (the comparative fitness index = .85; the root mean square error of approximation = .08) in this study. A sample item is shown for each process in Table 1. Each participant was asked to rate each item on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Never to 5 = Repeatedly). Cronbach’s alpha coefficients range from .53 to .83 (Table 1). One might consider that the reliability of the Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 495  S. HORIUCHI ET AL. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 496 Table 1. Sample item and Chronbach’s alpha coefficient of each subscale of processes of change measure for effective stress management*. Processe s of change Sample item Alpha Experiential processes Consciousness raising I search for information about how to deal with stress in a healthy way. .83 Dramatic relief I react emotionally to warnings about stress. .56 Environmental reevaluation I consider how managing my stress would benefit my family and friends. .77 Self reevaluation I feel good about myself when I use healthy strategies to manage my stress. .77 Social liberation I notice that managing stress is becoming a greater concern in our society. .69 Behavioral processes Self liberation I promise myself that I will take active steps to manage my stress. .73 Stimulus control I keep things at home that remind me to use healthy stress management techniques. .55 Counter conditioning When I start to feel stressed out, I take a short break to relax. .53 Helping relationships I have someone I can count on when I experience stress in my life. .65 Reinforcement management Friends and family say something positive when I use healthy strategies to manage stress. .71 *©2004. Pro-Change behavior systems, Inc. All rights reserved. measure is problematic, since some of alpha coefficients are lower than .70, indicating lower levels of internal consistency than preferred. These lower coefficients are still acceptable given that each sub-scale consists of a small number of items and measures a relatively broad construct. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of a factor is affected by the number of items and how broad a con- struct is. Each subscale consists of three items. Furthermore, since processes of change for effective stress management are broadly defined, the construct measured by each scale should be relatively broad. Stage of change was assessed using the Japanese language version of Pro-Change’s staging algorithm (Horiuchi, Tsuda, Tanaka, Okamura, Yajima, & Tsuda, 2009). First, the definition of effective stress management was provided to the participants. Then, the participants were asked whether they practice stress management in everyday life and were requested to select one of the following five items representing their stage of change: 1) “No. I have no intention to begin in the next six months.” (pre- contemplation stage); 2) “No. But I intend to begin in the next six months.” (contemplation stage); 3) “No. But I intend to begin in the next month.” (preparation stage); 4) “Yes. I have been practicing but for less than six months.” (action stage); or 5) “Yes. I have been practicing for at least six months.” (main- tenance stage). The item “No. I have not been stressed.” served to exclude respondents who did not experience stress. Twenty- seven female and 25 male students said they were not stressed and excluded from the following analyses. Stage of change for effective stress management may vary to some extent depend- ing on situational factors such as stressful daily events, so it is expected that the temporal stability of stage of change is mod- erate. A two-week test-retest reliability was moderate (κ = .40). Construct validity was confirmed by demonstrating that rela- tions to decisional balance were consistent with the predictions from the TTM (Horiuchi, Tsuda, Kobayashi, & Prochaska, 2012). Procedures An ethics committee at Kurume University reviewed this study. The paper-pencil survey was conducted in July 2010. During lectures, we asked 503 students to complete the ques- tionnaire in 10 - 15 minutes. An informed consent form was attached to the questionnaire. Eighty-two percent of the stu- dents agreed to participate, gave informed consent, and returned the completed questionnaire. The rest refused to participate or quit survey, and did not give informed consent. Statistical Analyses A raw score of each subscale was converted into T-score (M = 50, SD = 10). To test the first prediction, means were calcu- lated and compared by stages. To test the second and third pre- dictions, differences in the mean values of processes of change for stress management across the five stages were examined using an oneway multiple analysis of variance (MANOVA) with stage of change as an independent variable. The number of students analyzed was 166 male and 187 female students. Eta2 values of .01, .06, and .14 were interpreted as small, medium, and large, respectively (Cohen, 1988). Data was analyzed with SPSS 19.0. Results The stage distribution of the participants was as follows: 31.2% in the precontemplation stage, 12.5% in the contempla- tion, 12.7% in the preparation, 20.1% in the action, and 23.5% in the maintenance. Table 2 indicates the mean scores of ten subscales by the five stages. Individuals in the precontemplation stage showed the lowest scores in the subscales of consciousness raising, dramatic relief, self liberation, stimulus control, counter condi- tioning, and helping relationships. On the other hand, those of self-reevaluation, environmental reevaluation, social liberation, and reinforcement management were slightly higher in the contemplation stage than in the precontemplation stage. A MANOVA revealed a significant effect [F(40, 1287.3) = 2.10, p < .01, η2 = .06]. Table 3 shows a summary of the results at follow-up. There were significant stage effects for all pro- cesses (all, p < .01). Proportions of variance that were ac- counted for ranged from .04 to .08. These effect sizes were  S. HORIUCHI ET AL. Table 2. Means and standard deviations (in parenthese) of processes of change scores across stages. Precontemplation Contemplation Preparation Action Maintenance Consciousness raising 48.17 (9.55) 48.22 (9.02) 54.36 (9.86) 53.45 (11.62) 48.56 (8.48) Dramatic relief 47.58 (9.22) 49.82 (9.02) 54.91 (9.72) 51.05 (10.47) 51.30 (9.68) Self reevaluation 48.26 (9.75) 47.71 (8.54) 54.30 (8.71) 51.42 (10.65) 51.52 (10.41) Environmental reevaluation 47.64 (9.25) 47.18 (8.53) 53.47 (9.17) 52.40 (11.33) 51.67 (9.27) Social liberation 48.03 (9.50) 47.74 (8.36) 53.73 (8.80) 51.83 (11.40) 50.52 (9.10) Self liberation 47.78 (10.43) 49.08 (8.96) 53.26 (8.96) 51.71 ( 9.54) 51.46 (10.25) Stimulus control 47.11 (9.28) 50.08 (9.58) 51.85 (8.66) 52.66 ( 9.34) 52.16 (9.84) Counter conditioning 47.12 (10.27) 48.42 (9.77) 54.09 (8.71) 51.72 (10.27) 52.92 (8.84) Helping relationships 48.03 (9.24) 48.69 (9.28) 52.15 (8.59) 51.61 (10.27) 52.39 (10.26) Reinforcement management 47.13 (9.85) 47.07 (8.02) 54.39 (10.35) 52.81 (10.05) 51.51 (8.84) Table 3. Summary of the results of follow-up analysis of variance. F(4, 348) post-hoc η2 Experiential processes Consciousness raising 6.25** PC, C < PR, A PR, A > M .07 Dramatic relief 5.13** PC < PR .06 Self reevaluation 4.25** PC, C < PR .05 Environmental reevaluation 5.76** PC < PR, A, M C < PR, A .06 Social liberation 4.16** PC < PR .05 Behavioral processes Self liberation 3.63** PC < PR .04 Stimulus control 5.42** PC < PR, A, M .06 Counter conditioning 7.39** PC < PR, A, M .08 Helping relationships 3.55** PC < M .04 Reinforcement management 7.96** PC < PR, A, M .08 **p < .01. Note: PC = precontemplation; C = contemplation; PR = preparation; A = action; M = maintenance. small to medium. The results of post-hoc comparisons are also shown in Table 3. Briefly, with regard to experiential processes, the scores of five processes were significantly higher in the preparation than in the precontemplation stage. Those of consciousness-raising and environmental reevaluation were also significantly higher in the action stage. The use of only consciousness-raising was significantly higher in the preparation and action stages than it was in the maintenance stage. Other experiential processes did not show significant differences between the preparation, action, and maintenance stages. With regard to behavioral processes, the scores of self-libe- ration were significantly higher only in the preparation stage than in the precontemplation stage. The processes of stimulus control, counterconditioning, and reinforcement management were significantly higher in the preparation, action, and main- tenance stages than were those in the precontemplation stage. Finally, the score of helping relationships was significantly higher in the maintenance stage than were those in the precon- templation stage. Discussion This is among the first studies which examines the inter- stage differences of all ten processes with a reasonable sample size. The sample size of this study clearly exceeded the rea- sonable one estimated by power analysis which is 295. The TTM assumes specific relationships between processes and stages of change, which help design stage-matched interven- tions. We found a number of significant inter-stage differences in the processes which are consistent with the predictions from the TTM. Those results indicate strong relationships between stages and processes of change for effective stress management, and provide initial but important support for the applicability of processes of change to effective stress management. The results also indicate that the Japanese translation of processes of change measure having adequate concurrent validity. The results of this study indicated that the use of all processes of change significantly differ across the stages, which were mostly in line with those of Evers et al. (2000) which reported that the use of six processes was significantly different across Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 497  S. HORIUCHI ET AL. the stages. In contrast, the results of this study were not in line with those of Riley et al. (2008) which reported that the proc- esses’ use did not significantly differ across the stages. One of another interpretation of Riley et al. (2008)’ study was that whether significant differences might not be found due to the relatively small sample size. To exclude such possibility, we determined a reasonable sample size with power analysis. This determination enabled us to exclude such possibility. It is sug- gested that the processes’ use is different across the stages. With regard to process use in the precontemplation stage, we found that participants used six processes the least. The use of the other four processes was at least in the contemplation stage. No significant difference was found in processes’ use between the precontemplation and contemplation stages. Those results are consistent with the predictions from the TTM. Thus, the prediction was supported. With regard to experiential processes, it was predicted that those processes are more frequently used in the contemplation or preparation stage than in the precontemplation, and are lower in the action and maintenance stages than in the preparation stage. The difference between precontemplation and prepara- tion was significant in the predicted direction for all five expe- riential processes of change. Thus, the prediction was partially supported. In contrast, use of the other experiential processes unex- pectedly did not differ from the preparation to maintenance stages. These inconsistent results with the prediction may be explained by the fact that effective stress management requires daily behaviors to keep up the healthy activities. Individuals in the action or maintenance stage need to continue to engage in certain behaviors to manage stress, and they may have some need to continue to use the processes. These results suggest that it is necessary to consider such characteristics of stress man- agement when applying the processes of change construct to stress management. Further studies are needed to examine the roles of these experiential processes through the later stages and the plateau that may be reached. With regard to behavioral processes, it was predicted that behavioral processes are most frequently used at the action and maintenance stages. Four of five behavioral processes were higher in the action and/or maintenance stage than in the pre- contemplation stage, as predicted. An exception is that use of self liberation was found to be higher only in the preparation stage. Self-liberation is a process in which people make a commitment to behavior change, and it is assumed to be im- portant in the preparation stage so as to progress to action. These findings are largely consistent with the prediction. While extensive research has supported the TTM, the TTM has been also criticized for a linear relationships between stage of change and other TTM variables (Armitage, Sheeran, Conner, & Arden, 2004; Armitage, 2009; Sutton, 2000). Sutton (2000) reported that such relationships are problematic, since they suggest a pseudo-stage model. Non-linear patterns were found, however, between processes and stages of change. The applica- bility of processes of change to effective stress management was supported. The main limitation is that this study is based on cross-sec- tional data, and deals with inter-individual differences. Longi- tudinal research can examine whether the use of processes change with stage movement as predicted by the TTM, and can provide a stronger test of the theory. Such a longitudinal study would compliment and extend cross-sectional findings of rela- tionships between stages and processes of change which are consistent with the TTM. In addition, a cross-sectional study of Prochaska and DiClemente (1983) is one of the top cited papers in smoking control (Byrne & Chapman, 2005), showing that even cross-sectional research can produce high-impact results in behavior change research. Thus, cross-sectional examination on relationships between stages and processes of change for effective stress management is important as an initial step for validating the application of processes of change to effective stress management. Based on the results of this study, it will be necessary to examine intra-individual changes of the process use as an individual progresses from one stage to the next. A third limitation is that only processes of change were examined in this study. Since the effect sizes were small to medium, it is likely that other factors could also relate to stages of change. In future studies, it would be important to examine the other TTM variables—decisional balance and self-efficacy—as well as other stress-related factors such as the severity of stress of each participant. REFERENCES Anderson, N. B., Nordal, K. C., Breckler, S. J., Ballard, D., Bufka, L., & Bossolo, L. et al. (2010). Stress in America findings. American Psychological Association. http://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/stress/national-report.pdf Armitage, C. J. (2009). Is there utility in the transtheoretical model? British Journal of Health Psychology, 14, 195-210. doi:10.1348/135910708X368991 Armitage, C. J., Sheeran, P., Conner, M., & Arden, M. A. (2004). Stages of change or changes of stage? Predicting transitions in tran- stheoretical model stages in relation to healthy food choice. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72, 491-499. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.491 Byrne, F., & Chapman, S. (2005). The most cited authors and papers in tobacco control. Tobacco Control, 14, 155-160. doi:10.1136/tc.2005.011973 Cohen J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. DiClemente, C. C., & Prochaska, J. O. (1982). Self-change and therapy change of smoking behavior: A comparison of processes of change in cessation and maintenance. Addictive Behaviors, 7, 133-142. doi:10.1016/0306-4603(82)90038-7 European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions (2006). Fourth European working conditions survey. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Com- munities. http://www.eurofound.europa.eu/pubdocs/2006/98/en/2/ef0698en.pdf Evers, K. E., Evans, J. L., Fava, J. L., & Prochaska, J. O. (2000). De- velopment and validation of transtheoretical model variables applied to stress management. 21st Annual Scientific Sessions of the Society of Behavioral Medicine, Nashville. Evers, K.E., Prochaska, J.O., Johnson, J. L., Mauriello, L. M., Padula, J. A., & Prochaska, J. M. (2006). A randomized clinical trial of a po- pulation- and transtheoretical model-based stress-management inter- vention. Health Psychology, 25, 521-529. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.25.4.521 Horiuchi, S., Tsuda, A., Tanaka, Y., Okamura, H., Yajima, J., & Tsuda, S. (2009). Stage of change distribution of stress management behav- ior in Japanese university students. Japanese Journal of Health Promotion, 11, 1-8. Horiuchi, S., Tsuda, A., Kim, E., Hong, K.-S., Park, Y.-S., & Kim, U. (2010). Relationships between stage of change for stress manage- ment behavior and perceived stress and coping. Japanese Psycho- logical Research, 52, 291-297. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5884.2010.00444.x Horiuchi, S., Tsuda, A., Kobayashi, H., & Prochaska, J. M. (2012). The Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 498  S. HORIUCHI ET AL. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 499 reliability and validity of the Japanese version of Pro-Change’s deci- sional balance measure for effective stress management (PDSM). Japanese Psychological Research, 54, 128-136. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5884.2011.00490.x Japan Health Promotion & Fitness Foundation (1996). Attitude survey on health promotion FY 1996. Johnson, S. S., Driskell, M. M., Johnson, J. L., Prochaska, J. M., Zwick, W., & Prochaska, J. O. (2006). Efficacy of a transtheoretical model- based expert system for antihypertensive adherence. Disease Man- agement, 9, 291-301. doi:10.1089/dis.2006.9.291 Kopp, M. S., Skrabski, Á., Székely, A., Stauder, A., & Williams, R. (2007). Chronic stress and social changes, socioeconomic determina- tion of chronic stress. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1113, 325-338. doi:10.1196/annals.1391.006 Marcus, B. H., Rossi, J. S., Selby, V. C., Niaura, R. S., & Abrams, D. B. (1992). The stages and processes of exercise adoption and mainte- nance in a worksite sample. Health Psychology, 11, 386-95. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.11.6.386 Padlina, O., Aubert, L., Gehring, T. M., Martin-Diener, E., & Somaini, B. (2001). Stages of change for perceived stress in a Swiss popula- tion sample: An explorative study. Sozial- und Präventivmedizin, 46, 396-403. doi:10.1007/BF01321666 Pro-Change Behavior Systems, Inc. (2003). Road to healthy living: A guide for effective stress management. Kingston, RI: Pro-Change Be- havior Systems, Inc. Prochaska, J. O., Butterworth, S., Redding, C.A., Burden, V., Perrin, N., Leo, M. et al. (2008). Initial efficacy of MI, TTM tailoring and HRI’s with multiple behaviors for employee health promotion. Preventive Medicine, 46, 226-231. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.11.007 Prochaska, J. O., & DiClemente, C. C. (1983). Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: Toward an integrative model of change. Journal of Consulting and Clin ic al Psychology, 51, 390-395. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.51.3.390 Prochaska, J. O., DiClemente, C. C., & Norcross, J. C. (1992). In search of how people change: Applications to addictive behaviors. Am- erican Psychologist, 47, 1102-1114. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.47.9.1102 Redding, C. A., Prochaska, J. O., Pallonen, U. E., Rossi, J. S., Velicer, W. F., Rossi, S. R. et al. (1999). The transtheoretical individualized multimedia expert systems targeting adolescents’ health behaviors. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 6, 144-153. doi:10.1016/S1077-7229(99)80025-X Pruitt, S. L., McQueen, A., Tiro, J. A., Rakowski, W., Diclemente, C. C., & Vernon, S. W. (2010). Construct validity of a mammography processes of change scale and invariance by stage of change. Journal of Health Psychology, 15, 64-74. doi:10.1177/1359105309342305 Rosen, C. S. (2000). Is the sequencing of change processes by stage consistent across health problems? A meta-analysis. Health Psy- chology, 19, 593-604. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.19.6.593 Riley, T. A., Lewis, B. M., Lewis, M. P., & Fava, J. L. (2008). Low- income HIV-infected women and the processes of engaging in health behavior. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 19, 3-15. doi:10.1016/j.jana.2007.09.002 Sutton, S. (2000). Interpreting cross-sectional data on stages of change. Psychology and Health, 15, 163-171. doi:10.1080/08870440008400298 Velicer, W. F., Prochaska, J. O., Fava, J. L., Norman, G. J., & Redding, C. A. (1998). Smoking cessation and stress management: Applica- tions of the transtheoretical model of behavior change. Homeostasis, 38, 216-233. Watts, J., & Robertson, N. (2011). Burnout in university teaching staff: A systematic literature review. Educational Research , 53, 33-50. doi:10.1080/00131881.2011.552235

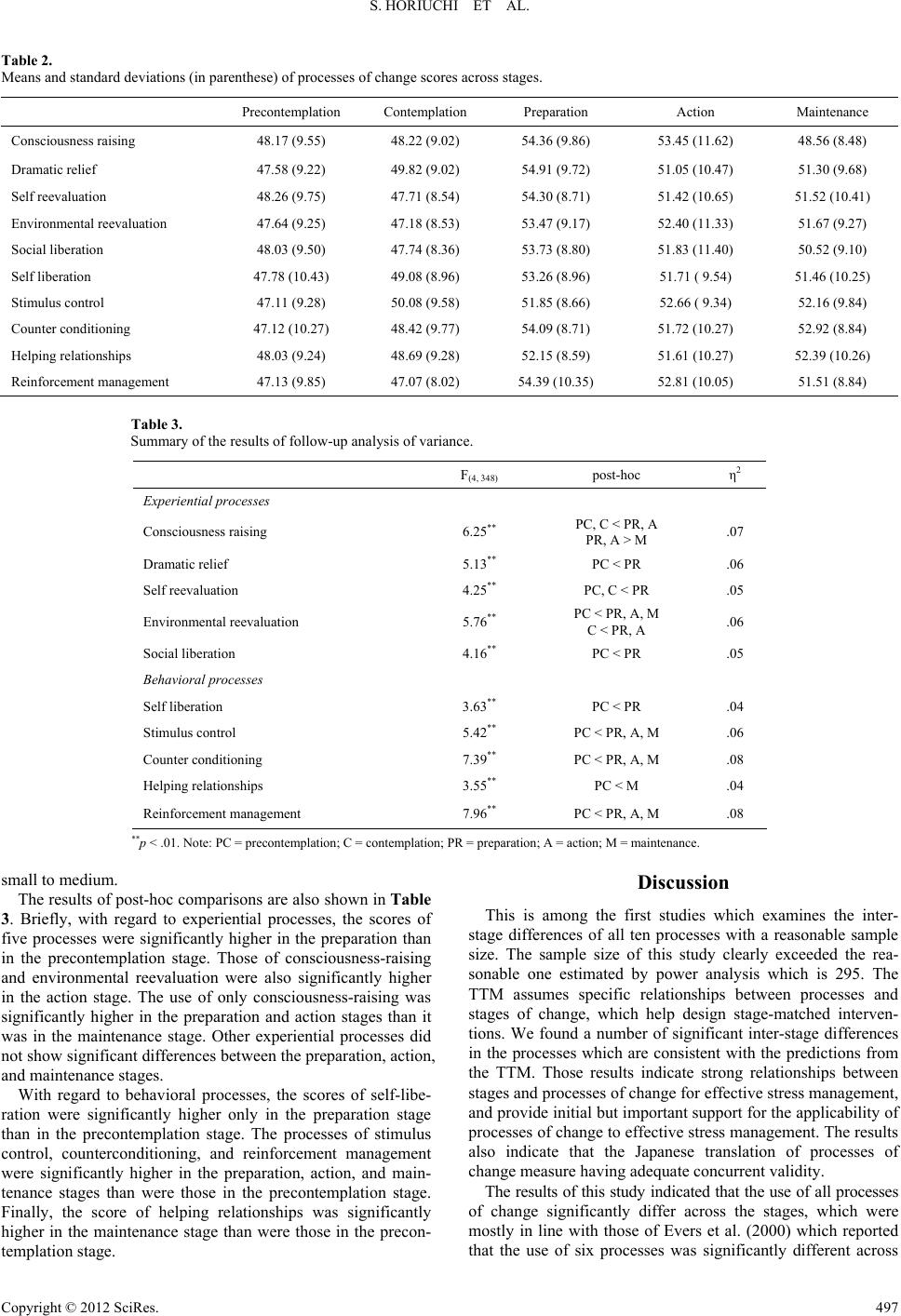

|